#i actually read a few articles on this symbolism from rabbis

Text

Wanna go Biblical? Let's go biblical.

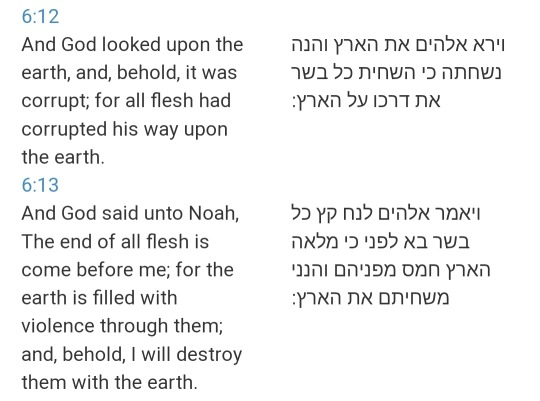

Raise you hand if you know the connection between: Noah's Ark story, and the biblical word חמס.

I don't know how coincidental this was, but for the Hebrew speaking person, the word "HAMAS" has an actual, biblical meaning:

Violent pillage and raiding, robbery (and any form of taking what's not yours), looting, overall violence, imoral behavior, oppression, and any possible associated wrongdoing. Rape would be within those definitions as well.

In the Bible, God tells Noah to build an Ark for those he intends to keep safe, for the land was "filled with hamas", and he plans to purge the evildoers with.... a great flood.

Who called for a Great Flood on the 7th? Who boasted of their acts and called them "flood" and "deluge"?

Now I may be Jewish, but I'm hardly anywhere as observant. I am secular. But I can recognize symbolism when I see one.

Genesis, 6

This word right there:

חמס

Reads "hamas".

The word occurs in biblical and religious texts many more times, in relation to bad rulers and sinning societies.

In this symbolic context, when Israel says. "HAMAS has embedded itself within the population of Gaza", what you also say is, "the Land is full of violence and immorality, and has to be purged of it".

In modern times, the two weeks prior to the incursion and counless calls for evacuation, the humanitarian corridor and the humanitarian zones are your Noah's Arks.

This is your local Jewish person with your daily does of Biblical symbolism, signing out.

#the word hamas in modern Hebrew is responsible for the name of the animal Hamos#which is#.... a ferret.#hamas war crimes#biblical symbolism#judaism#i actually read a few articles on this symbolism from rabbis#and it is very thought provoking

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jewish Magical Creatures/Beings (with recs)

So @biperchik was looking for some resources on Jewish magical creatures and I was going to make a short list and message them but then...this happened. Anyway, I’ve been planning on making some info posts since I just finished my Jewish Magic class. So I guess we’re starting here! I’ll be posting detail posts for different categories soon.

From what I have read I would say there are three major categories of “creature,” all anthropomorphic: golems, dybbuks, and demons. There are others that don’t fit into these, which I’ll list further down, but as far as I can tell these three categories are the main ones.

Golems:

· Schwartz has a section in Tree of Souls from pages 278 to 286 which covers pretty much all the main golem narratives. There are also a few passages in other sections which deal with golems, including in his creation of man section (some narratives say that Adam was a golem, which is a really interesting intersection of the two creation narratives in Genesis and I will blab about that later on my magic blog 😝)

· Goldsmith, Arnold L. The Golem Remembered: 1909-1980: Variations of a Jewish Legend

· Schäfer, Peter. “The Magic of the Golem: The Early Development of the Golem Legend.” Journal of Jewish Studies, vol. 46, no. 1-2, 1995, pp. 249–261., doi:10.18647/1802/jjs-1995 (This one is a journal article, I don’t know how accessible it is or what level of info you’re looking for)

· Golem! Danger, Deliverance, and Art by Emily D. Bilski. Haven’t looked at this one much but it has some cool art as well as the text which I have not read at all and it looks like it talks a lot about different portrayals (probably mostly modern/contemporary)

· Scholem, Gershom Gerhard. On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism. This is a book about Kabbalah generally; I know it talks somewhat about golems specifically and I think a number of other books on Kabbalah do as well since its tied in tightly with Jewish mysticism (because golems use name and letter magic and are almost always made by rabbis…I have words to say about “acceptable” acts of magic and elitism and patriarchy, but that’s a whole other rant)

· Golem by Moche Idol (haven’t looked at this but my prof recced it)

Dybbuks:

Other than Schwartz, I only have one rec for this: Between Worlds: Dybbuks, Exorcists, and Early Modern Judaism by J.H. Chajes. It gets pretty technical in some places (apparently, our professor had us skip them) but it’s pretty good and has a lot of information and narratives surrounding the exorcism of dybbuks in Early Modern Europe.

Oh, also Trachtenburg’s Jewish Magic and Superstition has a number of chapters on spirits.

Demons:

Okay so this category is really wide. I’m gonna give you some recs but mostly just subcategories to look into. Also infodumping because demons are my jam right now.

Jewish demonology goes back to at least the adoption of the Zoroastrian mythology into Jewish belief, since that is where a lot of this comes from. A lot of Jewish (and non-Jewish) demonology also comes from the gods of other surrounding societies.

Later Jewish demonology kind of faded into the background and Medieval/early modern European Jewish demonology is a lot less intricate and varied probably, but is also probably what most resources are going to be pulling from.

Joshua Trachtenburg’s Jewish Magic and Superstition is great and has a couple chapters dealing specifically with demons. It’s pretty old so it might be available for cheap/free, idk. My prof just posted literally the whole book in our resources for the class. It’ll also give you a lot of terms which might make finding stuff easier.

Schwartz has a big section on demons (and also Gehenna). It has a lot of older and more specific stuff too.

Different things to look for:

Lilith and the lilim are a big deal; Lilith is one of the very few specific demons that has survived into the medieval and early modern era.

Ashmadai is the king of demons (originally Zoroastrian). There are some stories about him and King Solomon from pretty early in the integration of his mythology into Judaism.

Another word describing demons in general is mazikeen/mazikeem

There’s a story called The Tale of the Jerusalemite which includes Ashmadai. A guy winds up in a town/kingdom of demons, some of whom study Torah. Ashmadai is really into Torah in the Solomon myths too. Trachtenburg talks about this also; its related to an idea that demons are constantly searching to become a more complete and perfect creation.

The main creation myth for demons is that they are unfinished because God started making them before Shabbos and had to stop, then left them that way in order to show the importance of keeping the Sabbath.

Magical creatures from other cultures were integrated into medieval/early modern European Judaism with a creation myth saying that they were the children of Adam copulating with a demon (possibly Lilith?) during his (100 year?) separation from Eve after leaving the Garden of Eden. Trachtenburg talks about this too.

More animal-like creatures (from the “mythological creatures” section of Tree of Souls, p. 144-151)

· Adne Sadeh, who doesn’t fit in this category because it’s a kind of primitive man but it is so freaking cool so I don’t care. They’re attached to the earth by an umbilical cord.

· Leviathan

o Sea monster

o Want dragons? Here is a dragon

o The Great Sea/Okeanos is on top of Leviathin’s fins.

o God takes this guy for walks

o We get to eat it in the World to Come

· �� The Ziz

o Big bird. Very big bird. The ocean only comes up to its ankles and one time its egg broke and flooded sixty cities

o Messenger of God

o We get to eat it in the World to Come

· The Re’em

o A horned creature kind of like a unicorn or rhino but like…big. Really big.

“A re’em that is one day old is the size of Mount Tabor” big.

· The Phoenix

o “the only creature that didn’t eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge.”

o Guards earth from the sun

o “Over a thousand years, each Phoenix becomes smaller and smaller until it is like a fledgling, and even its feathers fall off. Then G-d sends two angels, who restore it to the egg from which it first emerged, and soon these hatch again, and the Phoenix grows once again, and remains fully grown for the next thousand years.”

· The Lion of the Forest Ilai

o It’s like a lion but it roars super loud. I don’t know how big a parasang is but it made Rome shake from four hundred parasangs away.

o Basically there’s a line in Amos 3:8 that uses lions as a metaphor for G-d and the story says Caesar was like “hey lions aren’t that bad people kill lions” and Rabbi Joshua ben Haninah was like “um no not this lion.”

I really can’t recommend Tree of Souls enough. I’ve been writing fantasy for a long time and I was doing primarily Celtic paganism for a long time and that book really opened my eyes and showed me that I could find the things I was looking for in my own culture. That’s also where I learned about the Shekinah and started to feel like there might actually be a place for me in the religious part of this culture and I didn’t have to imagine G-d the way They’re portrayed in mainstream (and particularly Christian) culture. There’s a lot of great stuff in there, and everything has sources and annotation which make it a great jumping off point, as well. It’s HUGE so it might look intimidating if you’re not into that but all the individual myths are very short. Also I think Schwartz has some other books that might be less academic and tome-like.

476 notes

·

View notes

Text

TALMUD: Kiddushin 81b

So this blog is supposed to be me reading the Torah and writing Divrei Torah types of things but today I was the co-leader of a text from the Talmud so yes this is my first post on my Torah reading blog and no it’s not EvEn FrOm ThE tOrAh I’M SORRY but now this story is in my head and I want to discuss.

I actually read Parshat Bereishit this morning so I thought I would do that but I guess not lol.

So what we read is the story of Rabbi Hiyya bar Ashi and his wife from Kiddushin 81b.

Disclaimer: I don’t speak Hebrew so I am using the translation from https://www.sefaria.org/Kiddushin.81b?lang=bi

Another disclaimer: I really am extremely inexperienced in the Talmud so yeah please keep that in mind.

And another: This is incredibly jumbled I’m sorry!! My mind was wandering.

A summary of the story is that Rabbi Hiyya wasn’t really engaging in intercourse with his wife, and she saw him praying, “May the Merciful One save us from the evil inclination.” So then she was like, why is he praying about this if he never has sex with me anyway, “there is no concern that he will engage in sinful sexual behavior.” Then she decided to disguise herself as a prostitute named Haruta, and he had sex with her. He came home full of guilt and told her that he had sex with a prostitute. She told him that it had been her, and “he paid no attention to her” until she proved it to him. Then he says that either way, he didn’t know it was her, and so his intention was wrong. It ends with “All the days of that righteous man he would fast for the transgression he intended to commit, until he died by that death in his misery.”

So there are quite a few things to discuss here. In the beginning, he’s praying to be saved from the “evil inclination.” Is he talking about all sex? Adultery? Who knows.

Anyway, his wife hears him and then goes into his garden under the guise of a prostitute named Haruta (חרותא). Then, “he propositioned her”, and she asks for him to pay her with a pomegranate, and then they have sex.

(Pomegranates have a lot of symbolism in Judaism. Check out:

https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/9-jewish-things-about-pomegranates/)

TLDR; They symbolize fertility, love, the 613 mitzvot, so we eat them on Rosh Hashana, and they are one of the 7 species of Israel.

When he gets home, he goes and sits inside a fire his wife is making in the oven! And his wife says to him, “What Is This” and I agree because I think sitting in a fire is a little overdramatic lol. So he tells her that he had sex with a prostitute. She tells him that it was her, and he says, “I, in any event, intended to transgress.” Which I agree that even if you didn’t technically sin but you meant to it still counts as doing something wrong because the intent was there and I think a lot of people would agree with that.

I also wanted to point out that in the rest of Kiddushin 81b, it talks about other situations where people intended to sin but didn’t sin, or did not intend to sin but in fact they did sin, so maybe the focus of this story is supposed to be on that aspect and I think that’s important too. So that’s why I think the intent thing is important.

However, it does also say that even if you sin but you did not intend to it still counts. “And if with regard to one who intended to eat permitted fat, and forbidden fat mistakenly came up in his hand, the Torah states: ‘Though he know it not, yet is he guilty, and shall bear his iniquity’” And I think that’s important too. If you do something wrong and you don’t know it’s wrong then it’s still wrong. Maybe it was wrong of him to neglect his wife don’t ya think.

Something I was thinking about as I was reading this was about a husband’s sexual obligation to his wife. This comes from Exodus 21:10, “If he marries another, he must not withhold from this one her food, her clothing, or her conjugal rights.” There’s a lot of discussion in the Talmud about this as well. Ketubot 61b outlines that “Men of leisure, who do not work, must engage in marital relations every day, laborers must do so twice a week, donkey drivers once a week, camel drivers once every thirty days, and sailors once every six months. This is the statement of Rabbi Eliezer.” Ketubot 48a says that “Rav Huna said: With regard to one who says: I do not want to have intercourse with my wife unless I am in my clothes and she is in her clothes, he must divorce his wife and give her the payment for her marriage contract.”

I feel like the importance of intimacy in a relationship is very clear here and I wonder if they’d had any sort of discussion about it. I wonder why he wasn’t having sex with her. I mean clearly he didn’t have a problem with it, he had sex with her while she was disguised as a prostitute. I wonder if she spoke to him about it before she planned this thing. I mean she probably wanted to have sex with him, or else she wouldn’t have done this right? Also, in the beginning of the story it says that he wasn’t intimate with her due to his “advanced years”. But he did it with the “prostitute” so why not with his wife?

Anyway, Rabbi Hiyya feels so guilty about this that he was basically tormented by it and feeling guilty for the rest of his life and dies in misery. My friend made a really interesting point: Was he guilty about the adultery or the sex? When she tells him that she was the “prostitute”, his immediate reaction is to “pay no attention” to her because he thinks she’s lying to comfort him. Also, I’m just saying, how little attention do you have to give to your wife to not even notice that you are having sex with her. Seriously. He seems like a pretty neglectful husband in my opinion and I don’t think that’s supposed to be a celebrated thing.

I’m still wondering why he feels guilty. Someone else in the discussion I was having suggested that maybe he wasn’t actually guilty, but he didn’t want his image to be tarnished. But I don’t think so because he came home and admitted it to her right away. I don’t know. I mean I just usually wonder in general where guilt comes from. He kinda seems like he was worrying about having sex even when he wasn’t having sex. The whole reason his wife does this is that she notices him praying to not commit sexual sin but he doesn’t even have sex with her, so why is he praying about this? Does he just feel like sex is immoral?

He seems like a pretty neglectful husband in my opinion and I don’t think that’s supposed to be a celebrated thing.

The last line of the story is “All the days of that righteous man he would fast for the transgression he intended to commit, until he died by that death in his misery.” I thought throughout this story that the Rabbis are trying to teach a lesson that you shouldn’t treat your wife the way Rabbi Hiyya treated his wife. So I was confused as to why they would call him a righteous man.

In Hebrew, the word “righteous” is “צדיק”. It seems like a positive attribute, so I wonder why if this story is about a mistake he made, it uses that word? Interesting. My friend said that maybe they were being sarcastic, or maybe they were saying that even though he was a righteous man in other ways, he messed up in this way, so it tormented him until his death? I really could be completely off the mark here who knows. Just some random thoughts.

The last thing I want to mention is that this story was written by men, discussed by men, and women were not involved in the making or discussion of this story for many many many years even though it’s about a husband and his duties to his wife. And maybe an angle of this story is that there’s this deceitful wife who tricks her husband into sinning and the poor righteous man lives in torment. This is on my mind since, as I mentioned before, I read Parshat Bereishit this morning and something that really stuck out to me was that when Gd asked Adam if he ate of the forbidden tree, Adam’s response is “The woman You put at my side—she gave me of the tree, and I ate.” Oh please. What a guy. To immediately blame Eve (tbh he also kinda blames Gd a little bit too there) and take absolutely no responsibility for his own actions. Wow. I was very disappointed in him I gotta say.

Well, I guess I’ll be discussing that in my next post. :)

!להתראות

0 notes

Text

The UNITED STATE Battle Evacuee Board Aided Rescue Thousands Throughout the Holocaust—– In Spite Of Franklin Roosevelt

This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. A version of the article below was originally published at HNN.

It was a sight unlike any ever seen in the nation’s capital.

More than 400 rabbis, “most of them with shrub-shaped beards, many in silky cloaks with thick velvet collars” (as TIME magazine put it) marched to the White House just before Yom Kippur in 1943. They wanted to present President Franklin D. Roosevelt with a petition asking him to establish a government agency to rescue Jews from the Nazis.

FDR decided to snub the rabbis. He refused to meet with them or receive their petition for mercy. He even left the White House through a rear exit to avoid being seen by the rabbis. And he tried to block a subsequent Congressional resolution calling for creation of a rescue agency.

But four months later, on Jan. 22, 1944 — 75 years ago — President Roosevelt reversed himself and established the very rescue agency they were demanding, which he called the War Refugee Board. The remarkable story of FDR’s turnabout sheds light on America’s response to the most horrific humanitarian crisis of our time.

The Nazi Slaughterhouse

In December 1942, the Roosevelt administration and its allies publicly confirmed that the Germans were “carrying into effect Hitler’s oft-repeated intention to exterminate the Jewish people in Europe,” with “many hundreds of thousands of entirely innocent men, women and children” already having perished in “the Nazi slaughterhouse.”

But FDR was not prepared to go beyond a verbal denunciation of the mass murder. Spokesmen for his administration insisted there was nothing the U.S. could do to help the Jews “short of military destruction of German armies and the liberation of all the oppressed peoples,” as one official put it.

In reality, there were many avenues for U.S. action that would not have interfered with the war effort. For example, refugees could have been transported to the United States on Liberty troop-supply ships that were returning empty from Europe. The escapees could have been granted temporary haven to in U.S. territories such as the Virgin Islands.

Alternatively, many refugees could have been admitted to the U.S. within the existing immigration laws. Some 190,000 quota places from Germany and Axis-occupied countries sat unused during the Holocaust years, because the Roosevelt administration deliberately suppressed immigration below the levels permitted by law. The strategy for suppression was simple: “postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of the visas,” as Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long explained to his colleagues.

In short, the problem was not that rescue was impossible. The real problem was the attitude that prevailed in FDR’s White House and State Department. If there had been a will to rescue, ways could have been found.

Then fate intervened. In mid-1943, senior aides to Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. discovered that the State Department had been suppressing Holocaust news and blocking rescue opportunities. The aides began pressing Morgenthau to intercede.

“The bull has to be taken by the horns in dealing with this Jewish issue, and get this thing out of the State Department into some agency’s hands that is willing to deal with it frontally,” Treasury official Josiah E. DuBois Jr. told Morgenthau and other top aides. “You get a committee set up with their heart in it, I feel sure they can do something.” His colleague John Pehle agreed: “It seems to me the only way to get anything done is for the President to appoint a commission or committee consisting of sympathetic people of some importance.”

Jewish refugee advocates provided the vehicle for such action. A political action committee known as the Bergson Group began sponsoring newspaper ads and lobbying Congress to take the refugee issue away from the State Department. The Bergson activists came up with the idea of a rabbis’ march to Washington, and they made the demand for creation of a rescue agency the centerpiece of the rabbis’ petition.

“The Acquiescence of the Government”

In November 1943, U.S. Senator Guy Gillette (D-Iowa) and Rep. Will Rogers Jr. (D-California) introduced a resolution, drafted by the Bergson Group, calling on the president to create an agency to “save the surviving Jewish people of Europe from extinction at the hands of Nazi Germany.” The Roosevelt administration sent Assistant Secretary Long to Capitol Hill to block the measure.

Long testified to the House Foreign Affairs Committee that the resolution was unnecessary because the U.S. was already “very actively engaged” in doing whatever was possible to rescue Europe’s Jews. Long’s claims were sufficient to persuade the committee to set the resolution aside without a vote. Had matters rested there, the Roosevelt administration might have succeeded in snuffing out any momentum towards rescue action.

But when Long’s testimony was made public a few weeks later, it turned out he had wildly exaggerated the number of Jews who had been admitted. Long’s assertions were forcefully refuted in the press by Jewish organizations and other refugee advocates. As the controversy escalated in December, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee unanimously adopted the Gillette-Rogers resolution, and a full Senate vote was scheduled for late January 1944.

Secretary Morgenthau’s aides, who were closely monitoring the fight over the Gillette-Rogers resolution, pleaded with the Treasury Secretary to strike while the iron was hot. It was time to go the president, they urged—to explain to FDR that “it will be a blow to the Administration” if the full Senate were to adopt a resolution that would in effect rebuke him, just ten months before Election Day.

Morgenthau agreed that the congressional tumult gave him crucial ammunition. “I personally hate to say this thing, but our strongest out [with the President] is the imminence of Congress doing something,” the secretary remarked. “Really, when you get down to the point, this is a boiling pot on the Hill. You can’t hold it; it is going to pop, and you have either got to move very fast, or the Congress of the United States will do it for you.”

The Treasury staff had been gathering evidence of the State Department’s obstruction of rescue, and now they handed Morgenthau his main weapon: a stinging 18-page report, authored by DuBois and edited by his colleagues, titled “Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of This Government in the Murder of the Jews.” It thoroughly documented the whole sordid story of rescue opportunities that were obstructed, quotas that were deliberately left unfilled, and Holocaust news that was suppressed.

On Jan. 16, 1944, Morgenthau met with President Roosevelt in the Oval Office and presented FDR with an abbreviated version of the “Acquiescence” report (with the toned-down title, “Report to the President”). He included a draft of an executive order establishing a “War Refugee Board.”

DuBois had suggested that Morgenthau tell the president that if Roosevelt did not act, he (DuBois) would “resign and release the report to the press.” But Morgenthau did not need to go that far. He told the president he was “deeply disturbed” to discover that State Department officials were “actually taking action to prevent the rescue of the Jews.” Citing his father’s World War I-era efforts on behalf of Armenian genocide victims, Morgenthau said he was “convinced that effective action could be taken”—thus contradicting the administration’s longstanding line that Jews could be saved only by winning the war.

President Roosevelt recognized how embarrassing it would be to have the full Senate call attention to his administration’s stark humanitarian failure. The political cost of taking no action now outweighed his longstanding policy of not taking special steps to aid Europe’s Jews. Pre-empting congressional action by unilaterally establishing a rescue agency was the politically advantageous route. At the end of the 20-minute discussion, the president said, “We will do it,” and six days later he issued an executive order creating the War Refugee Board.

Token Rescue

Although understaffed and underfinanced, the War Refugee Board played a key role in the rescue of some 200,000 Jews and 20,000 non-Jews in the final 15 months of the war. Among other actions, it provided funds to bribe Nazis and shelter Jews, and facilitated and financed the life-saving work of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest.

But many more lives could have been saved if President Roosevelt had not been opposed to rescue before he was for it. For example, he could have established the War Refugee Board when refugee advocates first requested it, instead of fighting it tooth and nail for so many months. And he could have given the War Refugee Board proper funding, instead of providing only a token initial sum (90% of the Board’s budget had to be supplied by private Jewish organizations).

What a difference it would have made if FDR had extended some of his reputed humanitarianism to Europe’s Jews before most of them had been murdered by Hitler. Instead, as David S. Wyman wrote in his 1984 best-seller ‘The Abandonment of the Jews,’ “the era’s most prominent symbol of humanitarianism turned away from one of history’s most compelling moral challenges.”

Dr. Rafael Medoff is founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, and the author of The Jews Should Keep Quiet: President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, and the Holocaust, forthcoming from The Jewish Publication Society in 2019.

Read more: feedproxy.google.com

The post The UNITED STATE Battle Evacuee Board Aided Rescue Thousands Throughout the Holocaust—– In Spite Of Franklin Roosevelt appeared first on TheFeedPost.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2TPPhwg https://ift.tt/2ChxHHr

via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER — the famed Yiddish writer who in 1935 moved from Warsaw to New York and in 1978 received the Nobel Prize for Literature as an American-Jewish author — made his first trip to Israel in the fall of 1955, arriving just after Yom Kippur and leaving about two months later. His relationship to Israel was complicated to say the least. He had been born into a strictly religious family of rabbis and rebetzins in Poland, for whom the land of Israel was the holiest of religious symbols. But he also lived a secular life in 1920s Warsaw, witnessing Zionism overtake Jewish Enlightenment and Bundism as a viable 20th-century political force. In more personal terms, Israel was also the place to which his son, Israel Zamir, had been brought by his mother, Runya Pontsch, in 1938, growing up in part on Kibbutz Beit Alpha and later fighting in the War of Independence. Yet Singer had always avoided every kind of -ism — from Zionism to communism — and so his perspective on the young state of Israel was largely free of the ideology and dogmatism that was prevalent during the country’s early days.

During his trip, Singer published several articles per week in the Yiddish daily Forverts, recording his visit. While these articles sometimes read like touristic travelogues, they reflect Singer’s complex relation to the land of Israel, as both an idea and a place. Israel had been in Singer’s consciousness since his youngest days as a boy growing up in religious surroundings, and it made its way into his work, including some of his earliest fiction, which was published in Hebrew. When he was still living in Warsaw, Singer wrote a novella titled The Way Back (1928) about a young man full of the Zionist dream who travels to the Land of Israel and returns five years later after suffering hunger, malaria, and poverty. In 1948, just a week before the state of Israel was declared, he ended The Family Moskat with several characters leaving Warsaw and moving to pursue the Zionist dream. In 1955, just weeks before his trip, he published an episode of In My Father’s Court (1956) titled “To the Land of Israel,” about a local tinsmith who moves his family to the Holy Land, then returns disappointed to Warsaw, but then, despite everything, goes back. In his memoirs, Singer writes that he considered moving to British Mandate Palestine in the mid-1920s, and in The Certificate (1967), he fictionalizes this in a tale that ends with the protagonist instead going back to his shtetl. As late as 1938, in a letter to Runya sent from New York, he was still fantasizing about the idea: “My plan is this: as soon as I have least resources, and I hope they come together quickly, I will travel to Palestine.” But by mid-1939, these dreams seem to pass into a different view on reality: “For me, in the meantime, getting a visa to Palestine is impossible.” For Singer, it seems, Israel remained, in both the symbolic and literal sense, the road not taken.

And yet, in late 1955, Singer made his first trip to Israel, accompanied by his wife Alma, on a ship called Artsa traveling from Marseille via Naples to the port of Haifa — not as a religious child or an idealistic young man but as a middle-aged Yiddish writer who was beginning to make his name on the American literary landscape. And his journalistic assignment was to capture the trip in short articles that would give Yiddish readers across the United States a sense of what the young state of Israel was like. His son, Zamir, was in New York working as a Shomer Ha’Tsair representative, and both letters and memoirs suggest there was no question of his meeting Runya. Singer was left to his own devices — traveling throughout Israel with Alma, but writing about it as if he were there all by himself.

¤

Singer’s peculiar perspective — with such complex personal history behind it, and such pragmatic goals before it — gives his writing from Israel its unique tone. It is always concerned with the big picture yet remains focused on the small picture. This is evident from the first moments of his trip, even while he was still on the ship. “I think about Rabbi Yehuda Halevi and the sacrifices he made to set his eyes on the Holy Land,” he writes while the ship sails from France to Italy. “I think about the first pioneers, the first builders of the New Yishuv […] How is it that there’s no trace of any of this on this ship? Are Jews no longer devoted with heart and soul to the idea of the Land of Israel?” Singer is looking for proof of the spiritual greatness that the Land of Israel represents, and he wants to see it in the people on board with him — but he soon comes to understand that Israel is not a place of imagination, it’s a place that actually exists. “No, things are not all that bad,” he writes. “The fire is there, but is hidden […] The Land of Israel has become a reality, part of everyday life.”

He begins a keen description of reality still on board the ship. Observing the younger passengers, he describes a now familiar picture: “The young men and women who sit under my window on folding lounge chairs have possibly fought in the war against the Arabs. Tomorrow they may be sent to Gaza or another strategically significant location. But at the moment they want what any other modern young people want: to have a good time.” He identifies, before even arriving on shore, the constant negotiation in Israeli society between war and freedom.

On the ship, he also identifies cultural tensions between Ashkenazim and Sephardim, religious and secular:

There’s a tiny shul here with a holy ark and a few prayer books lying around. But the only people praying there are Sephardic Jews who are traveling in third class or in the dormitories […] It will soon be Yom Kippur, but the ship’s “Chaplain” […] told me there are only three Ashkenazim who want to pray in a quorum.

Singer becomes attached to this group of Sephardi Jews from Tunisia, following them with his eyes and ears:

On Friday evening I wanted to attend prayers. It was still daytime. I went into the little shul and there I saw a kiddush cup with a little wine left inside, and a few pieces of challah laying nearby. It seemed that they had already brought in the Sabbath. The Tunisian Jews have to eat at 6 o’clock and need to pray first.

Later, he goes again, and sees a man praying in a way that moves him. “There, in that little shul, I first came upon the spirituality for which I searched. There, among those Jews, it felt like shivat tsion — the Return to Zion.” He later watches the young Tunisian Jewish women with their head coverings down on the lower deck.

I look for the commonalities between me and them. It seems to me that they, too, look at me to see what connects us. From the standpoint of our bodies, we are built as differently as two people can be […] But as far as one may be from the other, the roots are the same […] There, in Tunisia, they looked Jewish, and for this they were persecuted.

What binds Jews from different corners of the world together, it seems, is their separate but shared experience of difference, even in their native countries.

Singer reports that the mood changes in Naples, where several hundred more passengers board the ship. Now there’s also singing and yelling — the fire he was looking for. But during this part of the trip he also meets a German-Jewish couple who complain bitterly about their life in the Yishuv.

The husband said that letting the Oriental Jews in without any selection, without any inspection, had completely thrown off the moral balance of the country […] The wife went even further than the husband. She said that, no matter how much she wished, she could not stand the company of Polish and Russian Jews. She was accustomed to European (German) culture […] she could not stand the Eastern European Jews.

Singer pushes back against her snobbery. “‘You know,’ I asked her, ‘that your so-called European culture slaughtered 6 million Jews?’” And she responds: “I know everything. But…”

Before he even sets foot in Israel, Singer identifies some of the social difficulties that its citizens face. “It’s hard, very hard, to bring together and bind together a people who are as far from each other as east from west […] Holding the Modern Jew together means holding together powers that can at each moment come apart. Herein lies the problem of the Yishuv.” This observation is less a criticism than a diagnosis. No matter how much binds Jews in Israel — the roots we all share — we have to, at the same time, navigate our differences. In this, Singer acknowledges one of the greatest challenges of a Jewish state.

What seems to really strike Singer when he finally arrives in Israel is the reality that, while built on modern organizational foundations established since the mid-19th century, the country appears as if it had been constructed out of nothing. His access to this reality is, funnily enough, street signs:

Israel is a new country, there’s a mixed population, for the most part newcomers, and they need information at every step. Signs in Hebrew — and often also in English — show you everything you need to know. […] The signs don’t just offer information, they’re also full of associations. . . Every street is named for someone who played a role in Jewish history or culture. Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, Ibn Gvirol, J. L. Gordon, Mendele, Sholem Aleichem, Peretz, Bialik, Pinsker, Herzl, Frishman, Zeitlin are all part of this place’s geography. Words from the Pentateuch, from the Mishnah, from the commentaries, from the Gemara, from the Zohar, from books of the Jewish Enlightenment – are used for all kinds of commercial, industrial, and political slogans.

What Singer seems to like about this is that it makes even less sympathetic Jews have to face their connection to Jewish history and culture. “The German Jew who lives here might be, in his heart, a bit of a snob […] but his address is: Sholem Aleichem Street. And he must — ten times or a hundred times a day — repeat this very same name.” In these signs, Singer sees something that goes much deeper into the reality and paradox of Jewish identity: its apparent inescapability.

Singer quickly connects these prosaic thoughts with the very core of Jewish faith: “As it once did at Mount Sinai, Jewish culture — in the best sense of the word — has brought itself down upon the Jews of Israel and called to them: you must take me on, you can no longer ignore me, you can no longer hide me along with yourself.” In Israel, spirit and religion are not ephemeral feelings; they are viscerally present.

¤

On his way from the port in Haifa to Tel Aviv, Singer stops at a Ma’abara, or transit camp, set up to house hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants and refugees, mainly recent arrivals from Arabic-speaking countries across North Africa and the Middle East. “It’s true that the little houses are far from comfortable,” he writes.

This is a camp of poor people, those who have not yet integrated into the Yishuv. But the place is ruled by a spirit of freedom and Jewish hopefulness. Sephardic Jews with long sidelocks walk around in turbans, linen robes, sandals, ritual fringes. There’s a little market where they sell tomatoes, pomegranates, grapes, bread, buns, cheese […] It’s true that there are no baths here or other such comforts. But the writer of these lines and our readers were also not all raised in houses with baths.

The poverty in these camps does not alienate someone like Singer, who himself grew up in poverty.

Singer recognizes both the desperation and the potential in these refugee camps:

The Jews here look both hopeful and angry. They have plenty of complaints for the leaders of Israel. But they’re busy with their own lives. Someone is thinking about them in the Jewish ministries. Their children study in Jewish schools. They are already part of the people. They will themselves soon sit in offices, speak in the Knesset.

It is as if Singer could see the long and difficult road ahead of someone like Yossi Yona — the academic scholar and Labor Party politician who was born in the Ma’abara of Kiryat Ata and now sits in the Knesset.

At every step, Singer reflects on his relationship to the reality of being in the modern Jewish state: “Moses, our great teacher, did not merit coming here. Herzl did not have the luck to see his dream realized. But I, who laid not a single finger toward building this state, walk around like I own the place.” His focus, at this early point of the trip, is mainly on the unbelievability of Jewish sovereignty. The question of its sustainability — the role of Palestinian Arabs within this project and the constant threat of war — is still to come. In the meantime, Singer basks in what he sees as the Jewishness around him: the history and culture with which he grew up, persecuted for hundreds of years in Eastern Europe, had finally risen and come to reign over an entire land and people. This unimaginable reality leads him to focus not on Israel’s relations with other people or states — its Arab population, the Palestinian refugees, the enemy nations across its borders — but rather on Israel’s national relationship to itself.

“There cannot be a Kibbutz Galuyot — an ingathering of the exiles — without the highest tolerance,” he warns.

Everyone in this place has to be accepted: the most orthodox Jews and the greatest apostates; the blonde and the dark-haired, the ingenue and the pioneeress, the Russian baryshnya, the American miss, and the French mademoiselle, the rabbinical Jewish daughters, and the wives that wear wigs with silk bands, and even the German Jewish fraulein who complains that Jews stink and that she misses the mortal danger of German culture.

This sentence is perhaps difficult to swallow today, and yet the divisions in Israeli society have only grown since Singer wrote this over 60 years ago. He could not have known the place that the Ultra-Orthodox would occupy in today’s Israel, or the great split in public opinion that would develop over territories occupied in the Six-Day War, or the strong shift to the right that the Israeli population has exhibited since the late 1970s. What he saw before him were Jews from different backgrounds, in different attire, with different beliefs and convictions, all living together in a single country. He immediately realized that, without tolerance for one another, the project would be doomed from the beginning.

It is worth scrutinizing this thought. Israeli society must deal fairly with others, but Israelis must also find a way of dealing fairly with each other. Respect for the unfamiliar begins with respect for the familiar — with the ability to see oneself in other people, and others in oneself. Where anger, destruction, and violence rule, they do so both inwardly and outwardly. If Jews cannot be good to Jews, this seems to suggest, how could they ever be good to anyone else?

¤

In his writing on Israel, Singer also constantly contemplates religious history and personal experience. In this spirit, he writes: “Ahavat Israel, loving fellow Jews […] has a mystical significance.” Singer cannot avoid associating the place with his own religious education as a child — being a Jew in Israel also means, for him, being constantly in touch with the myriad of Jewish texts he has internalized.

Standing at the foot of Mount Gilboa, he writes:

This was where Saul fell, this was where the last act of a divine drama was played out. Not far from here the Witch of Endor, the spiritist of the past, bewitched Samuel the Prophet. I look at this very same rocky hump which was seen by the first Jewish king, who had made the first big Jewish mistake: underestimating the powers and evil of Amalek.

Looking out from the balcony of a hotel in Safed a few days later, likely at Mount Meron, he writes: “This is not a mountain for tourists, or runaway fugitives, but for Kabbalists, who made their accounting with our little world. There, through those mountains, one can cross from this world into the world to come.” He continues:

At this very mountain gazed the holy Ari [Rabbi Isaac Luria], Rabbi Chaim Vital, the Baal-Ha’Kharedim [Rabbi Elazar ben Moshe Azikri], and the author of Lekha Dodi [Rabbi Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz]. Here, in this place, an angel showed itself each night to Rabbi Joseph Karo [author of the Shulkhan Arukh] and conducted nightly conversations with him. The greatest redemption-seekers looked out from this place for the Messiah. Here, in a tent or a sukkah, deeply gentle souls dreamed about a world of peace and a humanity with one purpose: to worship God, to become absorbed in the divine spirit, in a spirit of holiness, of beauty. This is where the Ari [Rabbi Isaac Luria] composed his Sabbath poetry, which was full of divine eroticism, and which had a depth with no equal in the poetry of the world.

In visiting Mount Zion, he similarly finds himself transported to a mystical past:

I look into a cave where you can supposedly find King David’s grave. I walk on small stone steps that lead to a room where, according to Christian legend, Jesus ate his last meal. […] This is another sort of antiquity than in other places. The antiquity here smells — it seems to me — of the Temple Mount, of Torah, of scrolls, of prophecy.

And elsewhere: “On this very hill there started a spiritual experiment that continues to this very day. In this place, a people tried to lead a divine life on earth. From here there will one day shine a light to the people of the world and to our own people.” And it seems that his sense of moral choice, raised by the danger of Jordanian soldiers looking down on him from the wall above, also finds expression: “What is today a desert could tomorrow become a town, and what today is a town could tomorrow become a desert. It all depends on our actions, not on bricks, stones, or strategies.” Walking through the Valley of Hinom, the historical site of Gehenna which he finds covered in greenery, he even jokes: “If the real Gehenna looked anything like this, sinning wouldn’t be such a terrible thing.” The images and symbolism of the Bible are truly present at every step.

The land as a whole has a strong effect on Singer, but his trip to Safed, as someone raised on the Kabbalah, made an especially strong impression. “I can say that here, for the first time, I gave myself over to the sense that I was in the Land of Israel.” These are moments when Singer’s sense of criticism, doubt, heresy, intellectuality, and all the other complex impulses that find their way into his fiction, takes second place to a deep sense of piety and faith. This is no less powerful in his work, where his characters achieve it rarely or partially, and, even when they do, with great difficulty.

Singer doesn’t come to this spiritual journal easily either. In Safed, he also encounters the reality of the new state. There he meets a Jew who speaks Galician Yiddish, but who is part of generations of Safed residents. “The Arabs of the past were good to Jews,” Singer quotes the man.

They let the Jewish merchants earn a living. When you bought grapes from them, they would add an extra bunch. Another man said: everything was good until the English came. They incited the Arabs against the Jews. Another man said: Well, may there soon be peace. This is atkhalta d’geula — the beginning of the redemption.

Among the mysticism and magic of the place are politics, colonialism, and history.

Later, in Tel Aviv, Singer visits a courthouse. In the first courtroom, Singer sees “a young man from Iraq who had allegedly falsified his documents in order not to have to go to the army.” In the next courtroom, a Greek Orthodox priest is taking the stand, speaking Arabic, which is being interpreted into Hebrew:

On the bench sit several Arabs […] They are suing to get back their houses, which the state of Israel took over after the Jewish-Arab War […] Jews have taken over their homes. But now the Arabs have decided to sue for their property back. They no longer have any documents, but they are bringing witnesses to testify that the houses that they own belong to them. The old Greek priest is one of these witnesses.

In a third courtroom, Singer observes a Yemenite Jewish thief who is accused of assaulting the police, but who claims the police actually assaulted him. The young thief ends up being acquitted. Ashkenazi Jews are conspicuously absent from this entire visit to the courthouse.

Singer soon observes other forms of suffering and injustice. On the southern side of the city, it is even more evident:

Here in Jaffa you can see that there was a war in this country. Tens and possibly hundreds of houses are shot up, ruined […] The majority of Arabs fled Jaffa, and in the Arab apartments live Jews from Yemen, Iraq, Morocco, Tunisia. They live in single rooms almost without furniture. They cook on portable burners. […] The situation in Israel is generally difficult, but in Jaffa everything is laid bare — all the poverty, all the difficulty.

Singer is, as that passage and most of his writing suggests, almost singularly focused on the new Jewish population of the state. The former Arab tenants of these apartment buildings remain invisible to him.

Singer is so utterly focused on the creation of the new state and the new Jewish settlers, that even when faced with the Arabic population, he barely acknowledges them. He writes, “In Beer Sheva, more than in other cities, you feel that you’re among Arabs. […] Arabs are not black but also not white. […] What sticks out to the eye most is the great amount of clothing that Arabs wear on the hottest of days. […] Rarely do you see Arab women on the street.” What is striking is the degree to which Singer sees Israel’s Arab population as an impenetrable other. He seeks no interaction with them, no attempt to understand them. He puts it plainly in another text: he just wants them to let Jews live their lives. Later, when he visits Jaffa, he writes: “As long as the Arabs leave well alone, there will be building-fever here like in Tel Aviv and in the rest of the country.” This is a difficult opinion to hear, but it has actually come to bear. Jaffa, more than 60 years later, is now going through a major revolution of gentrifying Jewish construction.

There is no doubt that Singer’s story of Israel is a Jewish story. His writing can deepen our understanding of different kinds of Jewish realities, even if, when it comes to Palestinians, his opinions are thoroughly unexamined and unconsidered. Singer can contribute, however, an interesting perspective on the need for tolerance among different kinds of Jews: Sephardic, Ashkenazi, old world and new. This is especially the case when it comes to modern Jews understanding the mindset of the old world. And it sets out a path for tolerance that can then be extended beyond Israel’s Jewish population.

¤

“I myself want people to speak to me in Hebrew,” Singer writes in one of his earlier articles.

But as soon as anyone hears that my Hebrew sounds foreign, they start speaking to me in Yiddish, and so the result is that I mostly speak Yiddish. People here speak Yiddish at every step. […] Even Sephardim learn some Yiddish in the army. It’s also in fashion for Hebraists to throw in Yiddish words to be cute.

Over and over, Singer’s wishes and imaginings of this place bump up against the reality. Everyday life — the texture of daily reality — pushes back against the big questions that seem to always be at hand. “A good cup of coffee is rare,” Singer writes. “You can get a good black coffee, but if you like a cup of coffee with cream like in New York, you will mostly be disappointed.” He also points out that “yogurt is very popular, as is a sort of sour cream called lebenya.” And another thing: “You see balconies everywhere. People sit on their balconies, eat on their balconies, entertain guests.” He points out that there are many elegant people on the streets but that well-dressed people are a rare sight. He even spends a paragraph on trisim, the heavy shades that are meant to keep out the Mediterranean sun. No matter the history, there is always real life to negotiate.

A major part of this real life, as Singer points out, is the constant threat of war. “The enemy can attack from all sides: from north, from south, from east,” Singer writes, reflecting on his trip up to Kibbutz Beit Alpha. “But the visitor in Israel is infected with a mysterious bravery that belongs to all Jews in Israel. A kind of courage that’s difficult to explain.” On Tel Aviv, he writes: “The enemy is not far. If you in New York were as close to the enemy as we are here, you’d shiver and shake and try to run away. But in the streets where I find myself there reigns a strange quiet, a serenity having something to do with the physical and spiritual atmosphere.” In Jerusalem, he again has the same thought: “It’s hard to believe that you’re close, extremely close, to the enemy.” And on the way up to Mount Zion, he again points to the mysterious courage: “I’m no hero, but I have no fear. I’d would say that Israel is infected with bravery. In any other country, this kind of walk, next to the very border of the enemy, would arouse fear in me.” Violence is a reality that Israelis face at all times — and there is no doubt that over the decades it has affected and perhaps also infected our society, both how Israelis treat non-Jews and how we treat each other. But the fact remains that, to live here, we all need an inherent kind of bravery, toward outside threats no less than our own neighbors.

¤

In one of his articles, in which Singer considers all the people he met during his trip, he tells the story of Benjamin Warszawiak, an old friend from Bilgoraj who moved to Israel. Benjamin found life difficult, moved for a time to South America, but eventually came back to live out his life working on a kibbutz. His story is sad, and yet Singer sees a redemptive aspect to this man’s life — that there is nowhere else but the Jewish state for him to live. “You don’t have to necessarily be an extraordinary person to have deep spiritual needs,” he reflects. “Simple people often sacrifice their personal happiness to improve their spiritual atmosphere. Israel is full of such people, and you find them especially in the kibbutzim. I can say that almost all of the kibbutzniks are in their own way idealists.”

Ultimately, Singer suggests, the paradox of Jewish life in Israel lies in the heart of the Jews who continue to make Israel their home. “Faith in this place, like the Sabbath, is somewhat automatic and instinctual too,” he writes. “The mouth denies, but the heart believes. How could people live here otherwise?”

¤

David Stromberg is a writer, translator, and literary scholar based in Jerusalem.

The post Faith in Place: Isaac Bashevis Singer in Israel appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2Jv7tXv

via IFTTT

0 notes