#imagine if Lots of artists All Across the Industry All said We have Morals Actually & We Will Not Make Shit until X Y Z

Text

update!

the family's GFM has met it's goal!

i am so relieved, thank you all for your help, i hope for nothing but their safety, health and peace; keep paying attention to the world going on, keep educating yourselves, and keep helping others in any small way you can, focus best you can without getting discouraged.

thank you for being the change we all need the world

#sporadic warbling#if i could do this for multiple GFMs sequentially i would#alas i am one outsider and was bumping up against the limits of what my audience can accomplish in a set time#imagine if Lots of artists All Across the Industry All said We have Morals Actually & We Will Not Make Shit until X Y Z#kind of pie in the sky of me but it'd be cool to be hit with a POSITIVE apollo ball for ONCE

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

some thoughts on comics

this has less to do with comics as they are in their current state in the industry and more about the artistry possible with the form, maybe even artistry in other mediums as well. this is something i’ve thought about a lot, and it’s rather long and a bit rambly, a bit elitist and maybe even pretentious, but i’d gladly appreciate it if you read it!

(this contains some spoilers regarding The Killing Joke by Alan Moore, the film and novel Drive, respectively by Nicolas Winding Refn and James Sallis, Devilman by Go Nagai and Persona by Ingmar Bergman.)

while discussing art with an art examiner, i came across a particular topic which has been bothering me for a while. i mentioned my interest in comics and their influence upon my work, and one way or the other, i can’t particularly remember how we got to the point before we moved on, she said “yes, but you need to use your influences in the high arts”.

a typically familiar distinction was made once again: comics are low-art, cheap and mass-produced, with little artistic viability; all visual arts besides it have the potential for high art.

had i been the person i was a few years ago, i may have agreed. i may have also extended the idea of “high visual art” being only possible within the classical mediums of visual art: painting, drawing, sculpting.

but as i’ve gotten a little older, a little more open-minded, and a little more willing to see things from others’ perspectives, i’ve realized just how much artistic expression is possible in other visual arts as well. photography, film, comics, collages, printing, 3D art, etching, animation. all of these visual mediums possess inherent strengths that can create extraordinary images, can communicate things otherwise impossible in other ways.

but, as i wrote in the title, this is about comics; or, maybe, more specifically, the concept of comics and their potential.

so, to give a definition of comics, let me use scott mccloud’s definition: “comics are juxtaposed pictorial and other images in a deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.”

this is ripped directly from mccloud’s book “understanding comics” (which is a great read and sort of inspired this write-up, i’d advise you to check it out) and while this may be the most accurate description of the form, it’s possible far more things may be done outside this definition, which could also fall under the idea of comics, but we will have to wait and see.

it works well for now, however, and can possibly, with a backwards look at history, relabel some pieces of art as comics. an example of this, given in “understanding comics”, is the triptych, which typically is 3 paintings placed alongside each other to convey an overlying idea within the culmination of the works, with each work conveying their own specific idea.

this gives one possible insight into the possibility of comics, and that is their ability to explore ideas in a “narrative” way via their images, whether it be actual narratives on display, or themes which link and provide context to each image.

in other words, comics can explore singular ideas belonging to larger ideas, with each piece of art in the sequence informing the context and/or meaning behind the others, providing a framework for the entire comic from which meaning can be derived for each individual artwork.

this ability of comics, for each piece in the whole’s meaning to be able to affect the overall whole meaning of the work, and vice-versa, falls under the idea of semiotics, and i believe it is this direct connection to semiotics which gives comics a large range of visual artistic expression beyond only narrative, beyond only language and beyond only imagery.

to give you an idea of why semiotics is such a powerful thing, let me illustrate for you; imagine a dog barking, wagging its tail, and running around in a field - see how it runs, jumps, and chases, in a friendly game, after a bird. now imagine a man, laughing, holding his belly, with a soft, loving smile on his face, a dog collar and leash in hand. finally, imagine a pickup truck parked in front of a house, its back canopy dirtied with mud and hair, with a man about to clean it up, a tired look on his face.

the logical association you could make here might be an obvious one: a man who loves his happy dog, after returning home from letting the dog run on a field, hates the process of cleaning his truck after bringing the dog back home in it. your mind has automatically made a logical framework to provide meaning to each idea shown.

but what if the man carried not a dog leash but now a shovel in the second idea? what if his face showed not happiness, but anger, hatred and disgust? the tired cleaning of the final idea can now carry a far darker association, yet it is entirely a created one within our minds. in fact, our entire perception of the relationship between the dog, the man, and the truck is created by ourselves.

and it is with this perception of the whole, with our mind creating a logical connection between each individual element that comprises the whole, that gives comics its ability to convey artistic themes extraordinarily lucidly and at the same time also give the potential of intentional ambiguity and different interpretation (this intentional ambiguity i believe being the most important part of what people classify as “high art”).

with this in mind, i believe comic artists have the ability to depict not only stories but thoughts and human ideas beyond the limitations of both narrative and visual arts in a vividly clear way which only our individual minds, informed as they are by our personal perceptions, can understand.

but it does not happen, or if it does, it does not happen nearly enough. and this, i believe, is why comics are perceived as a “low art”, that comics are only a form that can only communicate simply and explicitly.

so what are the limitations that, i feel, limit comic artists from being perceived as “high artists”, as artists with something serious to say in their respective form?

i believe there are many reasons, reasons beyond the control of artists themselves which i can understand immensely (such as comics being a form of industry, which limits artistry a lot), but there are some beliefs and ideas which i believe are perpetuated within and around the form that limits comic artists from fully utilizing the medium in an artistic manner (this is also where i have to engage some elitist opinions of mine but nevertheless i believe they are necessary).

1) Comic art =/= Fine Art

(please note that this is dealing with artistic proficiency, not artistic intent or authenticity)

this is usually the first reason why comic artists are dismissed as “low art”. narrative propels comics, usually, and with the narrative behind comics providing the necessary framework for meaning to be connected between each frame in a comic, this usually has the unspoken implication that art in comics does not have to be technically proficient, or at least proficient to the standard of “amazing art” which most people expect from the visual arts.

i think, if you’re on tumblr, you can inherently understand why this is ignorant. if not, if you’ve ever given visual art a proper go, you can also understand why this is wrong. if an example must be provided, please look at this

this was made by Ashley Wood, an illustrator and comic artist, for his comic Automatic Kafka. i think this demonstrates how comic artists can display remarkable technical proficiency, and why i think the idea of comic artists not being able to be as technically proficient as a regular “fine artist” is a flawed belief.

However, even if a comic artist is technically proficient, what often drags them away from being considered a “serious” artist is

2) good art and good writing =/= good comic

(this is also handled in scott mccloud’s book, i highly recommend “understanding comics” once again”)

now i might sound elitist here, but listen, i think this is something that needs to be vitally understood by anyone who believes in comics as “high art”/a serious art form: any visual story when driven by plot, by actions, by thoughts, by things which can be tangibly translated into language and have a narrative formed from that, is inherently going to be inferior as an art when compared to literature; maybe not all forms of literature, since lots of “low art” fiction relies immensely on imagery to create scenes or events (which would be rendered a lot more elegantly and simply in a comic), but it’s simply due to the fact that words are far more useful for many abstract ideas which cannot be communicated simply by images alone.

for example (and i’m going to use an example of a novel considered cheap, pulpy stuff to illustrate the problem here so that one gets the sense that it isn’t just “classic novels” that do narrative better than comics), if one takes a look at the film Drive by Nicolas Winding Refn, then compares it to the original novel by James Sallis (which, admittedly, the film adapted loosely), one will immediately notice the difference in tone between the two, but also what’s strikingly different is the way the Driver is characterised.

In the film, the Driver is portrayed as a stoic, quiet and friendly guy, a sort of Man With No Name, with a dangerously efficient, criminally-inclined hidden life, whereas in the novel the Driver is shown to interally monologue a lot, and often in a cynical and acerbic way, while being a sort of anti-heroic moral judge, giving further insight into the character’s relation to the rest of the narrative, while still illustrating the abstracted Driver from the film. this could not be done as easily in the film, nor would it contribute to the film at all and quite frankly the novel’s Driver is a lot less of a character appropriate for the film in general but ignore this for now

this illustrates the problem of comics being believed (both by audiences and creators) to be only a narrative-driven or art-driven form. with this i must say there is nothing wrong with comics being narratively driven, it is just incredibly reductive to think of the possibilities comics may have if they’re only seen as narrative-driven and/or art-driven.

and, this is going to sound very elitist of me, a lot of the stories presented in comics are very schlocky, convoluted and contrived, and do not use the medium to its fullest extent to work on possible themes as best as they could. even highly acclaimed comics are praised primarily on their story lines and/or their art, perhaps some may throw in a nod to panelling, composition and so on, but there is rarely appreciation for how these comics use the form of comics, and often times, they don’t, really (i’ve had a couple of friends admit to skimming over the art in various acclaimed comics and manga they’ve read, such as Watchmen, The Sandman, Berserk and Goodnight Punpun, because “they’re secondary to the story”).

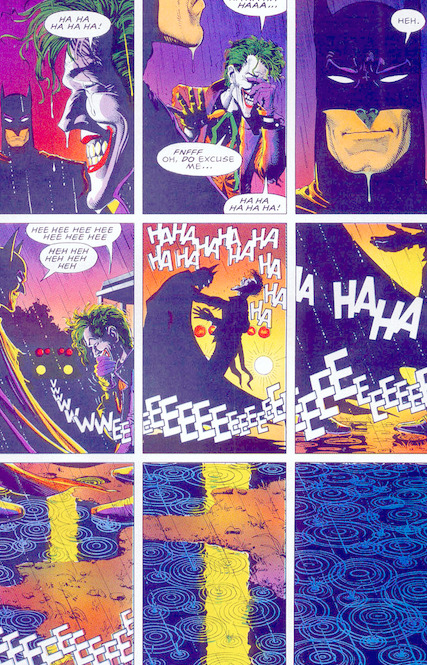

to give an example of how i think comic form can be utilized to its fullest in narratives in a very good way for that “intentional ambiguity” i mentioned earlier, i’ll use the last page of The Killing Joke by Alan Moore

this is the culmination of the entire story, and it ends ambiguously for the reader (i suggest reading the comic for the full effect of this page, plus it’s a really good comic).

is the joker being taken away by the police in the final panel? in the middle panel, is the joker being strangled, or is batman simply placing his hand on the joker’s shoulder? is batman laughing with or at the joker? is he being sympathetic, or is he trying to conceal his anger? does the laughter’s disappearance in the final 3 panels indicate resignation or death?

we’ll never know, and thus we’re given this ambiguity which we can weigh against ourselves, reflect upon as human beings, and use as an insight into the overlying theme of the work.

this may sound a little too serious for some, but I feel that dismisses the real issue here: it’s not about what approach an artist takes to approach their theme, nor what themes they have, it’s about how “seriously” they handle what they try to do - whether it illustrates the joy of familial love and care or the unseens horrors of war and their effect on everyday life, a certain level of gravitas should be employed by the artist to do so.

however, this comes to another point which i feel needs to be addressed, and it’s something i feel needs to be understood, as i feel it will help bridge the divide of comics and “high art”, or, more satisfactory, destroy the ridiculous barrier which prevents the form being appreciated or used for serious artistic expression, and that is

3) cliched and pulpy subject matter

(this is a bit of a rant and more rambling than my other thoughts, but i think this one is the main issue)

this ties in with a point i mentioned earlier, being that comics are seen as “narrative-driven” or “story-driven”. this often leads to extraordinarily convoluted plots having lots of “plot logic” and “lore” to justify many of the events that occur, as well as give a scenario for the emotional climaxes occur and for the themes to be explored.

now, let me say here, in addition to the earlier point about “serious handling of subject matter”, i personally, and i think some may agree with me, cannot stand having long and unnecessary trimmings surrounding a core theme, nor do i think justifications need to exist for anything and everything; if it works towards the emotion or ideas being explored, it works.

for example, Devilman by Go Nagai is a pulpy action horror manga, that is its primary intent and the general expectation one gets going into it. i don’t really think i can get much exploration of any themes in the work beyond an “eh” touching on an anti-war theme in the second half with subsequent rereadings, but as a primarily action-focused manga with the intent being to entertain, Devilman is just perfect for that. there’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s first and foremost a pulpy story, done interestingly and satisfyingly; anything further than that is entirely a reading of my own, since everything else within the work contributes to its main explicit intention of the work.

it wants to create a fictional reality where the events in the story can occur, so it does that, and it does that knowing the story as its end to the means of the plot’s logic and events, nothing more (i think this is where most people get irritated by seeing others do in-depth analyses of anime, manga and general other “trashy” stuff like 80s horror B-Movies but I digress).

i’ve got a big space opera dealing with the horrors of war. i do not see why i would need to divorce war from its inherently political-social implications on earth.

i’ve got a fantasy chosen one journey, with elves, orcs and warlocks, with a side-theme of racism. yes, this may add interest to the fictional world created, and that may be interesting to consider when applied to real life, but it is honestly too distant, too alienated from the context of real life to adequately consider in real life, and i feel that that cheapens the value of any possible interpretation or intended meaning.

(do note that i am not derriding people who wish to such with fiction, with comics, or with any form of art, but i feel this is simply the issue that causes such a divide between “high art” and “low art”.)

let me use an example of what i feel handles its artistic expression well, without the trappings of logic or subject matter (thus moving into that “intentional ambiguity” which i feels gives serious art its timeless quality), though it is a film: Persona by Ingmar Bergman (something which i’ve had a couple thoughts on, which i plan to write on).

this film, from what i understand, deals with the personas which make up one’s self, and how our personas, even if we try to distance them from ourselves, are ourselves. how it does this is not shown in a structured, logical or plot-driven way, even if there is a plot which gives context and drive to the events being able to explore it. it instead uses the elements of film to explore this in ways which only film could: acting, imagery, sound, continual movement of time. when the lead characters enter the beach house in the film, reality become less rigid in structure, as it seems to merge with dreams (hallucinations even), and things don’t generally seem to work within reality’s logic, but instead operate for the needs of the emotion, the themes, the ideas that wish to be conveyed.

and that’s how the film “works”; not because of the material around what the artist wants demanding things be this way,or that, but allowing what is wished to be expressed instead steering the artist and their internal artistic logic. it is this whole idea which is expressed by the entire work that should be given priority, not the clutter, i feel, and the minor ideas surrounding this whole idea should give both insight into the meaning of the whole idea, as well as its surrounding informing our perception of its own individual meaning.

and, as i’ve said before, this is semiotics, and comics have the most direct connection to it in all artforms outside maybe film, and as our entire human consciousness is formed from individual experiences and elements from which we derive meaning in both their entirety and in their individual context, this is why i think comics have such immense potential for artistic expression: they are the easiest way for us to express, as closely as possible, the human mind.

thank you for reading!

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

I arrive early at the LA hotel where I'm meeting Game of Thrones star Gwendoline Christie, and my first impression of the actor is formed in a millisecond when I bump into her in a hallway. Unusually and ethereally beautiful, towering above me, there's no mistaking the 39-year-old who stars as the indomitable Brienne of Tarth in the must-watch TV series, and who is reprising her role as the villainous Captain Phasma in Star Wars: The Last Jedi. (She first played the kickass stormtrooper in the previous chapter, 2015's The Force Awakens.)

Wearing a see-though black Fendi top and narrow trousers, her blonde hair is wavy and bobbed. With her porcelain skin and 191-centimetre stature, she could easily look intimidating. But her bright smile makes her approachable, so I tell her, in an embarrassing babble, that I love her work and that my two daughters are huge fans. She seems delighted, as though compliments are not at all commonplace.

Is she enjoying Hollywood stardom? "I don't think I would ever term myself as a Hollywood star… ever," she responds with a loud laugh, while admitting that "things seem to be going quite well". That sounds like an understatement. "Well it's always great, isn't it, when you feel a level of creative fulfilment in your work?" says Gwendoline in her lovely melodic voice.

She has every reason to be in good spirits. Her film career is in flight and life post-Westeros looks exciting. She has loved Star Wars since she was six, she tells me later, ushering me into her hotel suite and settling beside me on the sofa, poised, hands clasped. "Everyone wants to be in Star Wars. It is such a huge global phenomenon; I desperately wanted the role."

The latest instalment in the franchise sees Mark Hamill's Luke Skywalker in a prominent role with an apparently shocking twist. There will also a strong focus on a new generation of characters, including purple-haired Vice-Admiral Holdo, played by Laura Dern.

Since the release of The Force Awakens, Gwendoline's "chrome trooper" has become a fan favourite. "Phasma seems to have ignited a lot of curiosity," she says. "The idea of a woman exhibiting a violent attitude is not something we see a huge amount of in mainstream media."

There is speculation that Phasma has a much bigger role in the upcoming film, directed by Rian Johnson, but inevitably the actor is giving nothing away beyond referring to her character as "a threatening presence".

Can she say anything about the plot, which continues the story of the powerful Rey (Daisy Ridley), Finn (John Boyega) and resistance pilot Poe Dameron (Oscar Isaac)? "Well, no." A few seconds of dead air are interrupted by a hearty laugh.

She is less restrained about her excitement at working with one of her role models, Carrie Fisher (General Leia Organa), the Hollywood legend who died suddenly at the end of last year. "Princess Leia spoke to me," says Gwendoline of the original Star Wars. "She felt different, she was smart and she was strong."

No wonder Gwendoline was "very, very starstruck" when she was introduced to Fisher. "When I meet someone I admire like that, I keep myself as far away as possible from the person, you know, don't bother them, eyes down at the floor. I am overcome with shyness. But, actually, Carrie was incredibly warm. Everyone around her felt electrified by her wit and humanity. She was so open about her struggles with mental illness. The sheer force of personality is ravishing."

The same could be said of Gwendoline. It's no coincidence that the characters that have defined her career so far have been warriors ranging across the moral spectrum, from Brienne of Tarth – all goodness and altruistic selflessness – to the pure evil of Captain Phasma.

She inhabits the kind of roles that are still rare for women. Brienne of Tarth, for example, is considered to be plain looking. "It has been thrilling for me to play her, particularly since she is a woman much maligned by society due to the way she looks," she says.

As for Captain Phasma, audiences didn't even get a glimpse of her face in The Force Awakens, the stormtrooper being clad from head to toe in metal.

"I've never really placed a huge emphasis on people's physical being," she says. "I remember Carrie Fisher referring to her body as her 'brain bag'."

It's a subject that fascinates the actor, who is as intellectually curious as she is warm and funny. "We are so used to seeing images of women who are mostly conventionally attractive, and frequently scantily clad, and I found that a little restrictive," she says. "We have had a homogenised view not just of women, but really of the world. I think we all want to see ourselves represented [on screen] in some way."

She has an affinity for playing outsiders, "characters that feel like they aren't seen and don't fit in. Most of my life I have felt somewhat outside of the conventions of society – and certainly outside the conventions of the acting community."

Gwendoline was born and raised in West Sussex, "the only product of my mother and father". She is deliberate about her choice of words, avoiding the term "only child".

In fact, she describes her early life as "idyllic – I grew up in the countryside surrounded by fields and forests. I used to play outside all the time. I was generally alone, but I loved to read."

Away from the sanctuary of her close-knit family, however, life was difficult. "I absolutely hated school because I was bullied quite a lot." She was bookish and "really enjoyed being in the library, but I didn't enjoy the other students".

Was she bullied because of her height? "I don't think it was just my height." She pauses. "I don't know. I'm really not interested in talking about the bullying; what I am interested in is transcending that, because there is too much of an emphasis on suffering. We need to look at how we overcome it."

She explains her own coping mechanism: "I looked for where the sunshine was – for those who'd be more accepting and stimulating."

As a child, Gwendoline threw herself into hobbies – dancing and rhythmic gymnastics (she had to stop because of a spine injury at age 11). "Retrospectively, I realise what I loved about gymnastics was the rigour of being disciplined and precise, and then applying the flow of emotion and imagination to that."

Films provided "escapism", she says, singling out Orlando (1992), directed by Sally Potter, as "important". I can't help mentioning that she has been compared to the film's star, Tilda Swinton. "Well, that is an incredibly generous comparison," she exclaims. "I think she is a truly exceptional artist; she is doing her own thing."

It's something Gwendoline has always done, too. Her parents were "incredibly supportive" and there's a story that when she was young her father told her, "You can do anything a boy can do."

"He didn't use those exact words," says Gwendoline. "But he did say, 'There's no reason why you can't achieve anything.' "

Intent on acting from an early age, she recalls watching films as a teenager and wondering why the women's parts were so often boring. "When we studied classical plays at school, I wanted to play the male parts. I didn't understand why women would be treated in a certain way just because they were women. It didn't make any sense. A lot of things didn't make any sense."

Life began to make more sense when Gwendoline left school and enrolled in art college. "I became friends with artists working in the fashion industry, and musicians. That is really where I found my family – unconventional people who were totally accepting of themselves in all of their colourfulness and extreme personalities."

She went on to study acting at Drama Centre, London – "a conservatoire with a classical training and method approach" which she describes as life-changing. "It was hard, 12 hours a day, six or seven days a week. It was psychologically rigorous. You were broken down and sometimes criticised. It caused you to have an internal investigation of who you were, and that gave me confidence. They trained us to be artists."

In her early 20s, Gwendoline also began working for the actor Simon Callow (Outlander, Four Weddings and a Funeral). "He gave me an enormous amount of confidence," she says. "He also educated me. He had an incredible house filled with music and books, and I looked after his two wonderful dogs. He is one of the closest and most trusted people in my life."

With Callow's support, Gwendoline's career took off via well-reviewed stage performances and supporting roles in films including The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, before being cast as Brienne of Tarth in 2011. In doing so, she defied predictions that she'd find it difficult to work because of her height.

In fact, her stature and dramatic looks played to her advantage. With friends in the world of couture – she was interested in fashion long before art college – Gwendoline was in high demand as a model and became a muse of Vivienne Westwood. These days, she often collaborates with her partner of five years, British fashion designer Giles Deacon.

She won't discuss her relationship with Deacon, citing her need for a private life that's just that. "Because of the phantasmagorical nature of being an actor, you have to have your own reality," she says.

She explains that her "friends, family and partner form such an essential part of that reality that I do everything I can to get home, to see people as much as possible – because it is that life which is going to feed your work".

Steering the subject back to her career, she happily tells me she is about to work alongside Steve Carell in The Women of Marwen. And she is enthusiastic about her recent role in Jane Campion's Top of the Lake: China Girl, the sequel to Campion's award-winning 2013 TV drama. In it, she played Miranda Hilmarson, a Sydney police officer assigned to work with detective Robin Griffin (Elisabeth Moss) investigating the death of a woman whose body washes up on Bondi Beach.

A confirmed Campion fan, Gwendoline wrote to the New Zealand director pleading to be cast in the series, which also stars Nicole Kidman.

"I love Jane because she is interested in women, in a fairer balance between men and women, and she is very interested in the subject of misogyny." She adds that Top of the Lake: China Girl "deals with what it is to be a woman and a mother, what it is to deal with feeling marginalised".

Other than spending time with friends and family, Gwendoline's current focus is firmly on her career. So, what are her goals? "To create my own material – write it, direct it, design it, produce it. That is what I would love to do – if I wasn't so idle and lacking in imagination!"

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Press: Warrior woman: How Gwendoline Christie escaped the pressure to fit in

The Sydney Morning Herald – I arrive early at the LA hotel where I’m meeting Game of Thrones star Gwendoline Christie, and my first impression of the actor is formed in a millisecond when I bump into her in a hallway. Unusually and ethereally beautiful, towering above me, there’s no mistaking the 39-year-old who stars as the indomitable Brienne of Tarth in the must-watch TV series, and who is reprising her role as the villainous Captain Phasma in Star Wars: The Last Jedi. (She first played the kickass stormtrooper in the previous chapter, 2015’s The Force Awakens.)

Wearing a see-though black Fendi top and narrow trousers, her blonde hair is wavy and bobbed. With her porcelain skin and 191-centimetre stature, she could easily look intimidating. But her bright smile makes her approachable, so I tell her, in an embarrassing babble, that I love her work and that my two daughters are huge fans. She seems delighted, as though compliments are not at all commonplace.

Is she enjoying Hollywood stardom? “I don’t think I would ever term myself as a Hollywood star… ever,” she responds with a loud laugh, while admitting that “things seem to be going quite well”. That sounds like an understatement. “Well it’s always great, isn’t it, when you feel a level of creative fulfilment in your work?” says Gwendoline in her lovely melodic voice.

She has every reason to be in good spirits. Her film career is in flight and life post-Westeros looks exciting. She has loved Star Wars since she was six, she tells me later, ushering me into her hotel suite and settling beside me on the sofa, poised, hands clasped. “Everyone wants to be in Star Wars. It is such a huge global phenomenon; I desperately wanted the role.”

The latest installment in the franchise sees Mark Hamill’s Luke Skywalker in a prominent role with an apparently shocking twist. There will also a strong focus on a new generation of characters, including purple-haired Vice-Admiral Holdo, played by Laura Dern.

Since the release of The Force Awakens, Gwendoline’s “chrome trooper” has become a fan favourite. “Phasma seems to have ignited a lot of curiosity,” she says. “The idea of a woman exhibiting a violent attitude is not something we see a huge amount of in mainstream media.”

There is speculation that Phasma has a much bigger role in the upcoming film, directed by Rian Johnson, but inevitably the actor is giving nothing away beyond referring to her character as “a threatening presence”.

Can she say anything about the plot, which continues the story of the powerful Rey (Daisy Ridley), Finn (John Boyega) and resistance pilot Poe Dameron (Oscar Isaac)? “Well, no.” A few seconds of dead air are interrupted by a hearty laugh.

She is less restrained about her excitement at working with one of her role models, Carrie Fisher (General Leia Organa), the Hollywood legend who died suddenly at the end of last year. “Princess Leia spoke to me,” says Gwendoline of the original Star Wars. “She felt different, she was smart and she was strong.”

No wonder Gwendoline was “very, very starstruck” when she was introduced to Fisher. “When I meet someone I admire like that, I keep myself as far away as possible from the person, you know, don’t bother them, eyes down at the floor. I am overcome with shyness. But, actually, Carrie was incredibly warm. Everyone around her felt electrified by her wit and humanity. She was so open about her struggles with mental illness. The sheer force of personality is ravishing.”

The same could be said of Gwendoline. It’s no coincidence that the characters that have defined her career so far have been warriors ranging across the moral spectrum, from Brienne of Tarth – all goodness and altruistic selflessness – to the pure evil of Captain Phasma.

She inhabits the kind of roles that are still rare for women. Brienne of Tarth, for example, is considered to be plain looking. “It has been thrilling for me to play her, particularly since she is a woman much maligned by society due to the way she looks,” she says.

As for Captain Phasma, audiences didn’t even get a glimpse of her face in The Force Awakens, the stormtrooper being clad from head to toe in metal.

“I’ve never really placed a huge emphasis on people’s physical being,” she says. “I remember Carrie Fisher referring to her body as her ‘brain bag’.”

It’s a subject that fascinates the actor, who is as intellectually curious as she is warm and funny. “We are so used to seeing images of women who are mostly conventionally attractive, and frequently scantily clad, and I found that a little restrictive,” she says. “We have had a homogenised view not just of women, but really of the world. I think we all want to see ourselves represented [on screen] in some way.”

She has an affinity for playing outsiders, “characters that feel like they aren’t seen and don’t fit in. Most of my life I have felt somewhat outside of the conventions of society – and certainly outside the conventions of the acting community.”

Gwendoline was born and raised in West Sussex, “the only product of my mother and father”. She is deliberate about her choice of words, avoiding the term “only child”.

In fact, she describes her early life as “idyllic – I grew up in the countryside surrounded by fields and forests. I used to play outside all the time. I was generally alone, but I loved to read.”

Away from the sanctuary of her close-knit family, however, life was difficult. “I absolutely hated school because I was bullied quite a lot.” She was bookish and “really enjoyed being in the library, but I didn’t enjoy the other students”.

Was she bullied because of her height? “I don’t think it was just my height.” She pauses. “I don’t know. I’m really not interested in talking about the bullying; what I am interested in is transcending that, because there is too much of an emphasis on suffering. We need to look at how we overcome it.”

She explains her own coping mechanism: “I looked for where the sunshine was – for those who’d be more accepting and stimulating.”

As a child, Gwendoline threw herself into hobbies – dancing and rhythmic gymnastics (she had to stop because of a spine injury at age 11). “Retrospectively, I realise what I loved about gymnastics was the rigour of being disciplined and precise, and then applying the flow of emotion and imagination to that.”

Films provided “escapism”, she says, singling out Orlando (1992), directed by Sally Potter, as “important”. I can’t help mentioning that she has been compared to the film’s star, Tilda Swinton. “Well, that is an incredibly generous comparison,” she exclaims. “I think she is a truly exceptional artist; she is doing her own thing.”

It’s something Gwendoline has always done, too. Her parents were “incredibly supportive” and there’s a story that when she was young her father told her, “You can do anything a boy can do.”

“He didn’t use those exact words,” says Gwendoline. “But he did say, ‘There’s no reason why you can’t achieve anything.’ ”

Intent on acting from an early age, she recalls watching films as a teenager and wondering why the women’s parts were so often boring. “When we studied classical plays at school, I wanted to play the male parts. I didn’t understand why women would be treated in a certain way just because they were women. It didn’t make any sense. A lot of things didn’t make any sense.”

Life began to make more sense when Gwendoline left school and enrolled in art college. “I became friends with artists working in the fashion industry, and musicians. That is really where I found my family – unconventional people who were totally accepting of themselves in all of their colourfulness and extreme personalities.”

She went on to study acting at Drama Centre, London – “a conservatoire with a classical training and method approach” which she describes as life-changing. “It was hard, 12 hours a day, six or seven days a week. It was psychologically rigorous. You were broken down and sometimes criticised. It caused you to have an internal investigation of who you were, and that gave me confidence. They trained us to be artists.”

In her early 20s, Gwendoline also began working for the actor Simon Callow (Outlander, Four Weddings and a Funeral). “He gave me an enormous amount of confidence,” she says. “He also educated me. He had an incredible house filled with music and books, and I looked after his two wonderful dogs. He is one of the closest and most trusted people in my life.”

With Callow’s support, Gwendoline’s career took off via well-reviewed stage performances and supporting roles in films including The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, before being cast as Brienne of Tarth in 2011. In doing so, she defied predictions that she’d find it difficult to work because of her height.

In fact, her stature and dramatic looks played to her advantage. With friends in the world of couture – she was interested in fashion long before art college – Gwendoline was in high demand as a model and became a muse of Vivienne Westwood. These days, she often collaborates with her partner of five years, British fashion designer Giles Deacon.

She won’t discuss her relationship with Deacon, citing her need for a private life that’s just that. “Because of the phantasmagorical nature of being an actor, you have to have your own reality,” she says.

She explains that her “friends, family and partner form such an essential part of that reality that I do everything I can to get home, to see people as much as possible – because it is that life which is going to feed your work”.

Steering the subject back to her career, she happily tells me she is about to work alongside Steve Carell in The Women of Marwen. And she is enthusiastic about her recent role in Jane Campion’s Top of the Lake: China Girl, the sequel to Campion’s award-winning 2013 TV drama. In it, she played Miranda Hilmarson, a Sydney police officer assigned to work with detective Robin Griffin (Elisabeth Moss) investigating the death of a woman whose body washes up on Bondi Beach.

A confirmed Campion fan, Gwendoline wrote to the New Zealand director pleading to be cast in the series, which also stars Nicole Kidman.

“I love Jane because she is interested in women, in a fairer balance between men and women, and she is very interested in the subject of misogyny.” She adds that Top of the Lake: China Girl “deals with what it is to be a woman and a mother, what it is to deal with feeling marginalised”.

Other than spending time with friends and family, Gwendoline’s current focus is firmly on her career. So, what are her goals? “To create my own material – write it, direct it, design it, produce it. That is what I would love to do – if I wasn’t so idle and lacking in imagination!”

Star Wars: The Last Jedi opens in cinemas on December 14.

Press: Warrior woman: How Gwendoline Christie escaped the pressure to fit in was originally published on Glorious Gwendoline | Gwendoline Christie Fansite

#gwendoline christie#game of thrones#got cast#Brienne of Tarth#star wars#Captain Phasma#The Force Awakens#Mockingjay 2#Commander Lyme#THG#The Hunger Game

33 notes

·

View notes