#internet and postal woes

Text

Blog

Decided to blog even without the internet, I've promised to keep some kind of record after never daring to have diaries and destroying old writings. It not only helps to record memories better but is part of the effort to allow myself to be seen and known even though there's a lot I don't talk about

// Mostly physical issues: you can kind of tell from gaps in creating or gaps in the day in general when i've been incapacitated by pain or exhaustion, so say, the lack of dog walks or cooking is a big tell: in 2019 I was doing them regularly. It's not exactly relatable and can be quite frightening to non spoonies and triggering to others so I record health issues and abilities with initials on a notepad instead. Besides my body steals the focus all the time, i'd like other things to get the spotlight for once! //

So here goes:

read more for super long post!

I should note that the soundtrack for the past week has been Seal: Kiss from a Rose non stop, overlapping, out of order, mostly the acapella stuff. You might think that's torture but it's not a bad song to have on loop considering we're entering the Wham, Mariah and xmas schlock season. Shoutout to the ADHD folks with constant snippets of ad jingles, catchphrases and songs -We all know there's worse to have playing in an unclosable background tab. There have been brief interludes of of the sung parts of Freebird because I can't see the word freebox without thinking "and this bird you cannot tame!" or "won't you flyyyyy-yyy freeeebird, yeah".

Monday:

I woke up to a double slap in the face. First: the internet wouldn't work and the box said disconnected. Second postal woes. We'll deal with this part first but both happened simultaneously.

Go to find M, she's half asleep with no answers. her phone will have some mobile data and was the main signup contact info.

I wanted this to be a shared responsibility not on my shoulders alone since i'm tech guy but if things go wrong they want to know why they weren't asked about decisions first, i make the tech decisions all the time. So that's why she's main on this new internet lease. as mentioned before i have an ongoing battle with guilt/shame and tend to spiral when something goes wrong like it's my fault (for doing x or not having a backup plan for x). it's irrational but powerful. I have to spend most of the day thinking *away* from things that are under my responsibility but go wrong no matter how busy things get, the thoughts still weedle their way in.

Okay so she has a text from Orange on *friday* saying they noticed the new company had our phone line details and they're cutting us off, one from Free that morning saying your new line is connected and functional so we just need a box to hook up and we'll have internet.

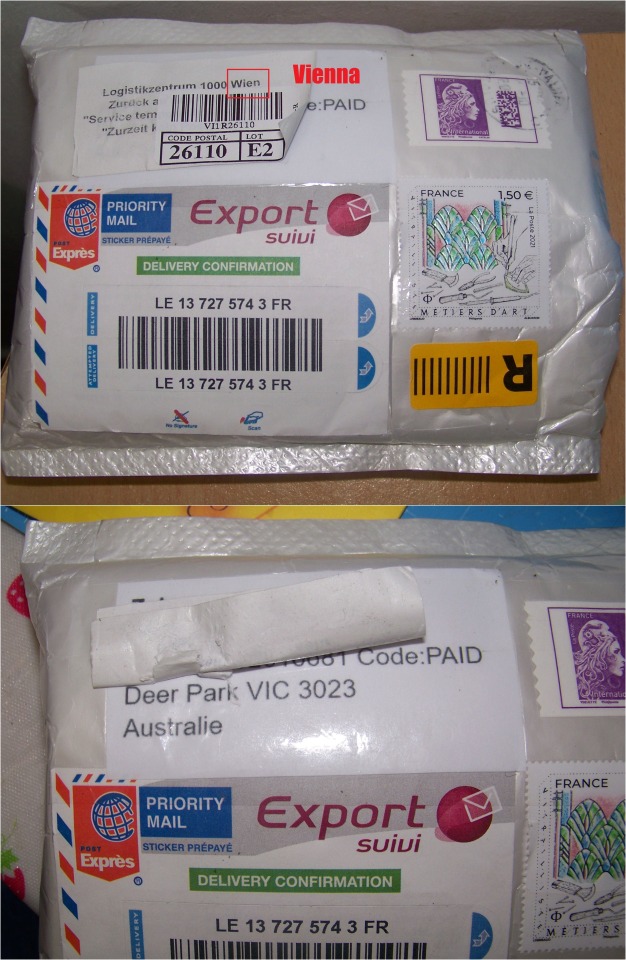

Second: I was asleep when the postman came: my letter with a few bratz clothes to AustrALIA, printed and carefully stamped with tracking stickers was sent to AUSTRIA, send back and fined 10€. There was a bunch of post so M paid up without asking why or what or even looking at the parcel, didn't think to ask for anything. Now I have to find way of contesting the fine or tax or whatever it was (no receipt!), finding out if post to Oz is going to have this issue again and somehow tell the customer. You can not make this kind of incomptence up.

but no internet = no answers. Look at this nonsense:

I spiral for a few hours anyway

I'd really like to do therapy again someday, I need adapted coping mechanisms to redirect thoughts. Going for a walk or body based mindfulness isn't an option.

Watched Colossal (dled in 360px from a streaming site back during the last internet drought). It's a great premise with solid acting, the metaphors are built in and it certainly has you white knuckled for the entirety of the third act but once it was over I found myself wondering if there was a meaning (I don't expect full resolution from stories about addiction or depression, in fact it annoys me if the person is magically better without some serious timeskip and ongoing work). It just sort of gave me 'this story is sort of an indie film and will have a point' vibes and ended up being a thriller, a solid thriller: just not what was expected. Oh wait, did I mention your immersion will be constantly ruined by the fact that Korea is a real place with real people with real lives? and you *will* want to kill the two leads, yes even the heroic one at the end... with no personal ethical problem at all: straight up murder the leads with your bare hands to save people who actually have a working moral compass. I was half hoping they'd have an end scene where there's a reveal and a lynch mob but that would be giving asian people some agency and this movie has no interest in that. Like they chose Seoul !!! of all places, to fill with expendable stupid person-shaped plot drones. Seoul has a quake plan, a nuke plan, a coup plan, a chemical attack plan, all men over 30 have been through military training, people are community minded and organise very effectively. They would leave the town evacuated except for skeleton crews manning the medical areas and military bases within 12 hours. Bet you $10 they have a joke military simulation for kaiju/mechas ready to go. But no they're plot ants going to turn up to be killed by a monster that appears in the same spot at the same hour everyday. What happened to inventing some exotic coded city or country? Why not set the monsters in Dallas or London (trust me, we are not prepared for much)?

My review, like that of Daredevil on netflix (yes that's an old grudge but I expected better) and The Suicide Squad 2020, is two middle fingers up out of ten stars for 'foreign' people as props: immersion ruined, story loses any impact, I don't care about your protagonists anymore, two hours of my time wasted on dreck that needed five minutes of thought instead of relying on a very tired old racist cliché. Who is greenlighting this 1960s B movie bad storytelling trope over and over again?

Does it not occur to them that a significant part of the audience will empathise with the city dwellers or factory workers or have been to a place that is strange and alien but also *people were still very much people*?

To illustrate: in The Boys (aka the series in the terrible tumblr ads) they had this scene of a bad guy being hunted through a block of flats and you're like ok I know this place, we've seen characters live in similar places, I've lived in places like this and the collateral damage the superhero does is horrifying and it tells you that the superhero is worse than any bad guy but then the superhero has this big scene where they say a slur and enjoy killing the bad guy slowly like 'Dun Dun villain alert' when the correct "oh shit" moment was when civilians were getting tossed out of windows. You know what I mean? You feel like you're being treated like a total idiot by a story when the person did a bad thing then the story has to double down and have them do a whole bunch more bad things- like you didn't get that it was a very bad thing the first time around. Maybe I'm just sick of the comic book, action hero and cop movies that treat death with no weight.

I think I'll watch Rachel's wedding Rachel getting married as a palate cleanser when the internet is back where the damage of addiction is given it's proper levity (even though it's going to be painfully cringeworthy).

I would 100% watch a remake or different version of the Colossal concept done smarter. The superhero facing consequences or with side effects makes for some really interesting media, i mean there are some terrible executions of the genre (avengers civil war) but done with even a little bit of thought? that's some delicious brain food right there!

Dolls on film (looks like Bandai Cutie Honey. set in Seoul 1987)

Lily is bored and being adorable. she's fully fluffy at the moment so she reads as a puppy even more than usual.

Tuesday:

Freebox arrives tomorrow. Thank the universe J's skype medical appointment got moved to friday.

Today I'm going to watch Chronicle (2012) to compare and contrast.

I wonder if the blonde guy's (DeHaan) voice is an affect to sound like a teen or his real voice? Michael B looking both too old for highschool and also so young. Oh nice: rules as soon as there's a mess. Good guys, I love these dorks. Their home movies are 3 idiots playing slap games, if they were brothers they'd have accidentally killed eachother by now. I'm glad they made both cousins awkward and socially isolated with one making a choice to work on connecting to people because the ND being the one to snap isn't true to life. Oh, wow, here we go...

OK that was good. Minimal shaky cam considering the medium. Escalation was handled with clues, clarity and a big trigger event so it wasn't a straight 'power corrupts' storyline. I think Jordan should have been the cousin, he's got the better acting chops, but yeah that was 2012 *cough*Not everybody came out of their Friday Night Lights binge with the right conclusions*cough* (still waiting for a certain actress to get her dues). I don't need answers about the nature of how things work but no anime references? it's 2012 and M.B. Jordan how do you pass up such a golden opportunity? LMAO.

The comparison to Akira has probably been done to death and The Craft has better lore on about using powers for good and TWO characters with emotional issues.

I'd rate this a solid 7/10 as a variation on the Akira story. Works well as "What if Peter Parker had a terrible uncle and wasn't whip smart?". A teensy bit on the fence about the atypical coding of blonde dude, I'd be less forgiving if they hadn't made his cousin a bit of a social disaster too. I loved that they connected telekenenis to flying, when characters can move stuff and themselves ... but not themselves from the ground it's a wierd thing for viewers/readers to buy into. The big fight was set at night which had me squinting to see who's where, so that lost it a point.

Finished Lagoonafire and yarn rerooted Gigi while listening to 3 "You are good" (formerly "what are dads") podcasts which has Sarah and Alex from "You're wrong about" talking about movies in a very informal not technical way. This was The Mummy, Guardians of the galaxy 2 and Birds of Prey.

I love them because they can take some seriously awful subject matter and do gallows humour that doesn't feel uncaring, they care a lot and take it seriously but life is tough and it's also ok to laugh about the absurdity of it. You've got a good dose of respect for the complexity of humans, lots of empathy but also they don't leave you feeling dirty, it's more like "here's the knowledge and context people had at the time, here's the knowledge we have now, it's ok to be furious at the injustice and let's keep these things in mind as we move forward because setting the record straight even for your one brain is a small step towards justice and that's a positive even though we just gave you twenty more reasons to hate humanity. Like if this was a twitter thread info dump you'd want to take up drinking right now but we're going to let you digest this with a bit of space gently". I don't know how they pull it off but they do. I thought "you're wrong about" was going to be confrontational or, worse, sensational but it's just debunking and education with a spoonful of sugar. Everything properly sourced and balanced like proper journalists not sloppy true crime/docuseries.

Not sure why I rerooted half of Lagoonafire to stick her hair in a ponytail but she looks amazing with her hair down too:

Wednesday:

woke up to find freebox physically set up thanks to J (my heart is bursting!!) now to fine tune the back end.

quickly sent emails. client in australia seems understanding (with a full refund).

#saf#dolls#my dogs#my_dogs#lily#monster high#reroot#internet and postal woes#colossal 2012#chronicle 2012#movie reviews

1 note

·

View note

Text

The postal service has become a key part of America’s election infrastructure

Law of the letter

The postal service has become a key part of America’s election infrastructure

Unfortunately it is also in a mess

“THE POSTAL service”, said Donald Trump, as he signed covid-19 relief legislation in the spring, “is a joke.” He contended that the United States Postal Service (USPS) is losing money by “handing out packages for Amazon and other internet companies”, and needed to quadruple its package rates. Far from being a joke, the USPS is the nation’s favourite government agency, viewed favourably by 91% of Americans. But it is losing money: $4.5bn from January to March, more than double its losses for the same period last year. Neither the reasons nor the solution are quite so simple—and many see ulterior motives behind Mr Trump’s contempt.

The USPS’s financial woes have three main causes, one acute and two chronic. The acute one is covid-19. At least 2,400 postal workers have caught the virus and 60 have died. More than 17,000 of its 630,000 employees have been quarantined. Although package volume and revenue has grown along with online shopping, the volume of first-class and marketing mail have both declined.

Chronic problem number one is the decline in first-class mail, the postal service’s most profitable offering. In a digital age people send fewer letters and postcards. Chronic problem two is the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act (PAEA), a law passed with bipartisan support in 2006 that requires USPS to prepay a large share of future retirees’ health benefits—a burden imposed on no other federal agency.

On current trends, the postal service estimates that it could run out of money sometime between April and October 2021, unless there is relief or reform. House Democrats included money for the postal service in their version of the CARES Act enacted in March, but after Steven Mnuchin, the Treasury secretary, said Mr Trump would veto any legislation that included funding for the postal service, it was cut. The only relief the USPS has so far been offered is a $10bn line of credit from the Treasury that lets Mr Mnuchin see the terms of its ten biggest contracts, which includes the one with Amazon (the USPS does a lot of “last mile” delivery for Amazon).

To put the service on firmer financial footing—or, some believe, to undermine it—Louis DeJoy, who became Postmaster General in May, implemented operational changes last month. Instead of setting as a paramount goal delivering to customers all mail received by a post office on a given morning, the new rules forbid carriers from leaving late or making extra trips back to the station, as often happens if more mail arrives than a single truck can hold.

Many question why Mr DeJoy opted to implement those changes just before a presidential election that will be unusually reliant on mailed ballots. Mr DeJoy, unlike the previous four postmasters general, has never worked for USPS; he ran a logistics company and has been a generous donor to Republicans. Gerry Connolly, a Democratic congressman who chairs the subcommittee that oversees USPS, calls Mr DeJoy’s rationale “a smokescreen...Under the guise of ‘We can’t afford it and we’re making efficiencies’, it’s directly affecting the delivery of mail on the eve of an election.”

Others posit different motives. Two years ago the Office of Management and Budget released a report mulling the sale and privatisation of the USPS, a position long advocated by some market-friendly wonks. Mr Trump has a long-standing grudge against Jeff Bezos, who owns both Amazon and the Washington Post. Some believe the president sees raising package rates as a way to exact revenge. The latest stimulus bill passed by the House contains $25bn for USPS, and removes any conditionality—such as letting Treasury see contractual terms—from its $10bn line of credit. This may not survive negotiations, or the threat of Mr Trump’s veto.

Mr Connolly is defiant. “We have a pandemic spreading; it’s more virulent than ever, the unemployment numbers are going up, GDP shrank by the largest number ever recorded, and you want to veto a bill over the fact you have your nose in a snit about Jeff Bezos and Amazon? Good luck on selling that.” The postal service too will be on the ballot in November—if the ballot papers can be delivered by USPS.■

This article appeared in the United States section of the print edition under the headline "Law of the letter"

https://ift.tt/31oFm2l

0 notes

Text

Will tech companies change the way we manage our health?

Cyrus Radfar Contributor

Cyrus Radfar is the founding partner at V1 Worldwide.

More posts by this contributor

Amazon isn’t to blame for the Postal Service’s woes, but it will need to innovate to survive

Dear United: Autonomous cars will pull you out of your seat

As of September 2018, the top 10 tech companies in the U.S. had spent a total of $4.7 billion on healthcare acquisitions since 2012. The number of healthcare deals undertaken by those companies has consistently risen year-on-year. It all points to an increasing interest from technology companies in U.S. healthcare, which raises many questions as to what their intentions are, and what the ramifications will be for the health industry.

It also begs the question as to why healthcare has become the latest target of U.S. tech giants. On the surface, they don’t seem like natural bedfellows. One is agile and quick, the other slow moving and pensive; one obsessed with looking forward, the other struggling to keep up with its past.

And yet, it’s true. Apple, IBM, Microsoft, Samsung and Uber have all flirted with healthcare in recent years, from data-collecting health apps and devices to a digital cab-hailing service for medical patients. Two of the most intriguing companies to make movements around healthcare recently, though, are Amazon and Alphabet. Both of them seem to have health insurance, in particular, set in their sights.

A is for: Alphabet, Amazon or Apple

Alphabet is currently the most active investor among large tech companies in U.S. healthcare, according to CB Insights. Via Verily, an Alphabet subsidiary that focuses on using technology to better understand health, and DeepMind, another Alphabet acquisition that deals in artificial intelligence solutions, the tech giant has been exploring how to use AI to tackle disease by using data generation, detection and positive lifestyle modifications. Alphabet has also made substantial investments in Oscar, Clover and Collective Health — companies that all have their eye on disrupting the health insurance sector.

Meanwhile, Amazon raised eyebrows by making its biggest move into healthcare last summer, when it acquired the internet pharmacy startup PillPack. Then, in October 2018, it filed a patent for its Alexa voice assistant to detect colds and coughs. Furthermore, the e-commerce business has been working on an internal project named Hera, which involves using data from electronic medical records (EMRs) to identify incorrect misdiagnoses. And in January of last year, Amazon announced a partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan for an employer health initiative — a thinly veiled tactic to better understand health insurance by using workers as beta-testers with an eye toward expanding into a public market further down the line.

Apple isn’t standing by quietly, either. It was recently announced that they’ve been working with Aetna since 2016 to provide incentives for healthy behavior to their customers through personalized exercise and health tips.

While all three are making strides in the healthcare industry, health insurance, in particular, seems like it may to be a major part of their long-term strategy for Alphabet and Amazon.

Can the tech giants cross the moat?

This isn’t the first time tech-savvy businesses have sized up the U..S healthcare and health insurance industries. They’ve been viewed as sitting ducks for disruption for many years. Unsurprisingly so, too. With their analogue systems, complex strata of silos and out-of-date technology, anyone would think they were primed and ready for digital disruption — that new technologies could help these out-of-date, yet highly lucrative industries, become more streamlined, efficient and customer-centric.

That’s what Better — a mobile experience for healthcare — thought when it was launched in 2013 by Health Hero co-founder and Rock Health mentor, Geoffrey Clapp. The startup struggled from day one with investments and the seemingly monumental task of applying a simple solution to a plethora of problems. Better admitted defeat just two years after it launched.

“We were doing concierge services across all disease states, across anatomic states like a knee surgery or a stroke, and at the same time doing bundled payment services and multiple, different payment structures,” Clapp said in 2016, when looking back at Better. “People may love the product, but they want it to address whatever problem theirs might be. And we talked ourselves into thinking we would have verticals.”

Health insurance is just as difficult a sector to disrupt as other areas of the U.S. healthcare industry, but is less appealing to startups due to the large resources companies need to have before they even enter the market.

Despite their size, capital and ingenuity, making inroads into the healthcare industry won’t be easy for tech companies.

An interesting case study over the past few years has been Oscar Health (which, incidentally, received $375 million in investment from Alphabet last year). Launched in 2012 under the proviso of using technology and customer experience insight to simplify health insurance, Oscar is often seen as the poster-boy of startups disrupting health insurance. However, its journey has been anything but smooth and, despite significant investment, its future is anything but clear.

The company has struggled to compete in the market for individual healthcare, as well as assembling the necessary network of doctors and hospitals. And while Oscar recorded its first profitable quarter in its now seven-year lifespan in 2018, it has a history of hemorrhaging money, including more than $200 million in losses in 2016. If Oscar is the success story of startups disrupting U.S. health insurance, then it’s a stark reminder as to how much of an uphill battle that is.

Of course, Amazon and Alphabet don’t have to worry about losing money in their long-term game plan for health insurance. But they still have to overcome the long list of regulations and pragmatisms that can’t simply be overcome by throwing money at the problem. They won’t automatically succeed on account of their size and resources, as Google learned when it closed the doors of Google Health in 2012, citing that the service “is not having the broad impact that we hoped it would.”

It seems that Alphabet, Amazon et al. have learned from their mistakes, the mistakes of their peers and those of startups like Better. Alphabet isn’t diving in head-first this time around. Instead, it’s tackling specific diseases, partnering with hospitals and applying its vast know-how in AI to combat real problems that affect millions of Americans. And Amazon — via its partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan — is taking the time to better understand the market it hopes to disrupt by taking a close look at its problems on a micro scale.

Grow or die

If the U.S. health insurance industry is indeed so difficult to conquer, it begs the question as to why tech companies are taking another swing at it. The simple answer is revenue.

The U.S. health insurance net premiums recorded by life/health insurers in 2017 totaled $594.9 billion. That’s more than three times Amazon’s 2017 revenue ($178 billion) and more than times that of Alphabet’s ($111 billion).

There’s more to it.

When a business’ annual revenue exceeds $100 billion, it’s sufficiently difficult to find new avenues of meaningful growth. This is problematic for companies like Alphabet and Amazon. Growth and scale are vital for them. Without them, the vultures begin to circle, believing that they’re losing their grip on their ecosystems — and with that, stock prices take a hit.

We’ve already seen the tech giants mitigate this risk by successfully expanding into other verticals in recent years. Whether it’s grocery delivery services, voice assistants or self-driving cars, tech businesses are constantly looking to expand their empires to fresh verticals. Healthcare is simply the next industry to be re-conquered.

Roadblocks along the way

Despite their size, capital and ingenuity, making inroads into the healthcare industry won’t be easy for tech companies, no matter how carefully they approach it. While they may seem to be old hands when it comes to disrupting industries, healthcare and health insurance are different beasts entirely.

For a start, there’s regulation. In order to sell and distribute drugs, there are complex and expensive hoops to be jumped through, overseen by regulatory bodies, including the FDA and the DEA.

There’s always been a question mark over how these companies use the vast swathes of data available to them.

Then there’s data and privacy. Tech giants may believe that technology gives them an upper-hand over the industry’s long-standing incumbents, but tech solutions require access to data that’s also regulated by strict privacy laws — a major barrier to be overcome for those looking to enter specifically into health insurance.

And on top of all of that, the tech companies looking to take on the health insurance would have to navigate the state-based insurance regulatory system. What works in Utah, which is generally regarded as a more lenient state when it come to insurance regulation, may not work in California, which is seen as one of the strictest states.

Privacy, data and universal healthcare

While there may be challenges facing new businesses in becoming major players in the health insurance industry, it would take a brave person to bet against them. If they were to succeed, some of the ramifications might not be appealing to everyone.

For a start, there’s always been a question mark over how these companies use the vast swathes of data available to them. Tech companies have been rocked in recent years by the public turning against them over how their data is used to turn a profit. But what if that data was used to calculate a customer’s insurance premium? It’s feasible that a user’s premium could go down if data shows they live a healthy lifestyle; for instance, they purchase healthy foods, have a gym a membership and track regular workouts through a device.

On the other hand, inactive users shown to buy unhealthy foods and products could see their premiums go up over time.

It’s a genuine concern according to Peter Swire, a privacy expert at the Scheller College of Business at Georgia Tech and the White House coordinator for the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy rule under President Clinton. “As far as I can tell, the Amazon website could use its information about the customer to inform its health insurance affiliate about the customer,” Swire says in an interview with Vice. “In other words, I’m not aware of rules that stop data from outside the healthcare system from being used by the health insurance company.”

Tangent: Will tech companies push against a single-payer or universal healthcare system?

I’ll pause a moment to put on my tinfoil hat.

As recently as 2017, Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini stated he’d be open to discussing a single-payer system, “Single-payer, I think we should have that debate as a nation.”

Single-payer or Medicare-for-all are both in the sights of progressive Democrats in Washington. Those fighting for a single-payer health system in the model of countries like the U.K. and Canada are already up against powerful lobbying groups from pharmaceutical and insurance industries. Game theory may tell us that adding the richest companies in the world to that group would surely push the idea of universal healthcare in the U.S. further away from reality.

This is a big, “what if” scenario that plagues me as we consider a future where the tech companies begin to create their own insurance solutions. They definitely would not want the government to come in and replace private insurance.

Let’s remove the tinfoil hat and we can return to the less conspiracy theory-themed conversation.

Better than the status quo

Of course, there’s no evidence to suggest that Amazon, Google or any other tech giant interested in exploring health insurance might use data against its users or lobby against universal healthcare. In fact, if there’s one thing these businesses know, it’s the importance of pleasing as many people as possible. They’re aware, often from personal experience, how damaging negative publicity can be — not just to a particular product or service, but to the whole business. Following nefarious money-making initiatives could destroy any hope of disrupting the health insurance industry before they’ve even begun.

We could imagine that tech companies would approach their solution with their special sauce.

Amazon may bring extreme efficiency, no frills and incredibly fast logistics to their offering. Google or an Alphabet company may come from an AI and predictive approach, wherein every person would have a health assistant backed by a field of specialists. Alphabet machines and kiosks you could drop into for a quick health check. Apple would bring their polished retail experience and love of control to create a vertical solution like what we see from Kaiser Permanente. They’d work to ensure the quality of the experience. Each company would, effectively, serve a different type of consumer.

If they decide to show their hand and go head-to-head with the health insurance industry’s current incumbents, they may do so by positioning themselves as the benevolent alternative that works for everyone in the system and is ultimately better, less expensive and more efficient. According to a 2017 McKinsey study, very few insurers are providing what the American people want from their providers, namely convenience, more incorporated technology, tools that promote health and wellness and greater value for the money.

These are areas where technologists often excel: providing high levels of customer care, improving services and driving down cost, and doing so by incorporating cutting-edge technology. If they can do that with health insurance, then they may well be within a shot of finally delivering on technology’s promise to disrupt an out-of-date industry.

Growth is the lifeblood of these companies, and the health vertical that is ripe for disruption is, coincidentally, vital to our survival. It’s going to be a fascinating battle when it plays out to see whether, like Uber’s cowboy start, tech companies can leapfrog regulation and force the hand of the legislatures with the help of consumer demand.

0 notes

Text

Coronavirus may give President Trump a long sought chance to privatize the Postal Service

WASHINGTON — Amid a cash crunch threatening to put the U.S. Postal Service out of business, the Trump administration is being accused of blocking bipartisan efforts to provide money to the agency as part of a long-sought conservative effort to privatize mail delivery.

The coronavirus pandemic has led to a precipitous drop in mail deliveries, worsening a crisis for an already financially troubled service. Last week, Postmaster General Megan Brennan said financial woes exacerbated by the pandemic could cause the agency to run out of money by October.

The $2 trillion coronavirus stimulus package passed on March 25 did not provide assistance for the Postal Service, despite bipartisan support for the funding, according to an aide to the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, which has jurisdiction over the Postal Service.

Instead, the legislation only allowed the Postal Service to borrow $10 billion from the Treasury Department.

“There was bipartisan support for direct appropriations to go to the Postal Service,” said a committee aide, who requested anonymity to discuss ongoing negotiations. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin “said you can have the loan or you can have nothing.”

Yet in the weeks since the stimulus passed, the Treasury Department has not approved the loan.

A spokesperson for Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee Chairman Ron Johnson, a Wisconsin Republican, did not respond to a request for comment.

A U.S. Postal Service worker wears a mask and gloves on April 9, 2020, in Van Nuys, Calif. (Mario Tama/Getty Images)

While the White House will not comment on the reason for the delay, American Postal Workers Union President Mark Dimondstein said the administration is using the loan to try to push privatization. He blames administration “idealogues,” including Mnuchin, for using the crisis “to push their privatization agenda.”

A spokesperson for the Treasury Department said Mnuchin and the White House are “supportive” of the loan.

“Treasury, including Secretary Mnuchin, has been in direct contact with the USPS multiple times this week, and we are working closely with the USPS to put the new $10 billion line of credit with the USPS into effect,” the Treasury spokesperson said in an email.

While the administration says it is working with the Postal Service, Ronnie Stutts, the president of the National Rural Letter Carriers Association, accused the White House and Treasury Department of blocking postal funding as part of an effort to privatize the agency.

“Everything was going good with this until they got to the White House,” Stutts said.

The Treasury Department and Trump want “to privatize postal service,” he added. “There’s no two ways about it. And when it got there, he killed it. They said no. He was not going to give us any money.”

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin at a daily briefing on the coronavirus at the White House on April 2, 2020. (Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images)

While the Postal Service is a quasi government agency, it is in a unique position since it has not been funded by taxpayer dollars since the 1980s. Instead, the post office relies on its own revenue from mail services.

While the Postal Service has made a profit, it has been facing financial woes since 2006, when legislation was passed requiring the Postal Service to pre-fund retirement for its workers. Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the Postal Service was already in dire straits with its liabilities and debt vastly outpacing revenue. Last year, the U.S. Government Accountability Office described the “overall financial picture” of the Postal Service as “deteriorating and unsustainable.”

The coronavirus has dramatically worsened this situation by causing a large decline in mail volume due to decreased commercial activity. The Postal Service saw a 24.2 percent decline in delivered mail volume during the week of March 29 to April 4 and delivered-mail volume was down over 30 percent for the first three days of last week, according to a presentation made by the Postal Service and distributed to members of Congress last week

The presentation, which was obtained by Yahoo News, predicted that there would be 35 billion fewer pieces of mail in the remainder of the fiscal year, which ends in September. The Postal Service is forecasting the declines to continue through the next fiscal year leading to a $23 billion increase in net losses over the next 18 months.

The presentation said the agency hopes to receive a $25 billion grant to cover losses related to the pandemic. It also said the Postal Service needs a $25 billion modernization grant to “weather the longer term economic impacts” as well as debt relief and additional borrowing authority.

A spokesperson for the Postal Service declined to answer questions and referred Yahoo News to a statement Brennan, the postmaster general, released on Friday describing the agency’s stimulus needs.

Stutts, the National Rural Letter Carriers Association president, said that even if Mnuchin approves the loans authorized by the last stimulus, it will not be enough to solve the Postal Service’s financial problems.

“Right now it’s approximately $11 billion that we’ve defaulted and it’s about 5.5 billion each year to pre-fund retirement. We just don’t have the money,” Stutts said. “It’s not going to be paid back. And if we borrowed $10 billion, it’s just going to put us further in debt.”

President Trump at the coronavirus response daily briefing at the White House on Friday. (Yuri Gripas/Reuters)

On April 7, during a coronavirus task force press briefing, President Trump dismissed allegations he was essentially trying to end the U.S. Postal Service.

“Oh, I’m the reason the Postal Service — the Postal Service has lost billions of dollars every year for many, many years. So I’m the demise? This is a new one. I’m now the demise of the Postal Service,” Trump said.

Trump went on to blame the situation on “internet companies,” including Amazon, which he has frequently accused of not paying enough for its use of the U.S. Postal Service.

“They lose money every time they deliver a package for Amazon or these other internet companies, these other companies that deliver,” he said. “They drop everything in the Post Office and they say, ‘You deliver it.’”

While the White House and Treasury Department did not respond to questions about whether the president or Mnuchin want to see the Postal Service privatized, they have signaled support for this approach in the past. In 2018, Trump issued an executive order that created a postal task force to identify potential ways to improve the agency’s financial woes. Mnuchin led that task force, and its final report advocated selling off parts of the service to private companies.

One major concern about privatization is that the Postal Service has a universal service obligation that requires it to deliver mail for equal rates anywhere in the country. This includes rural routes that are not necessarily profitable.

Dimondstein, the president of the American Postal Workers Union, noted private companies do not have any similar obligation. Other companies, he said, can pick and choose where they want to go.

“The Postal Service can’t, shouldn’t and won’t,” he said.

_____

Click here for the latest coronavirus news and updates. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please refer to the CDC’s and WHO’s resource guides.

Read more:

What to do if you think you have the coronavirus

What are the symptoms of coronavirus?

New Yahoo News/YouGov coronavirus poll shows Americans turning against Trump

Doctors rethinking coronavirus: Are we using ventilators the wrong way?

Coronavirus good news: Community camaraderie, cute pets, funny videos and more

Life after pandemic: How will coronavirus change us?

%

from Job Search Tips https://jobsearchtips.net/coronavirus-may-give-president-trump-a-long-sought-chance-to-privatize-the-postal-service/

0 notes

Text

Will tech companies change the way we manage our health?

Cyrus Radfar Contributor

Cyrus Radfar is the founding partner at V1 Worldwide.

More posts by this contributor

Amazon isn’t to blame for the Postal Service’s woes, but it will need to innovate to survive

Dear United: Autonomous cars will pull you out of your seat

As of September 2018, the top 10 tech companies in the U.S. had spent a total of $4.7 billion on healthcare acquisitions since 2012. The number of healthcare deals undertaken by those companies has consistently risen year-on-year. It all points to an increasing interest from technology companies in U.S. healthcare, which raises many questions as to what their intentions are, and what the ramifications will be for the health industry.

It also begs the question as to why healthcare has become the latest target of U.S. tech giants. On the surface, they don’t seem like natural bedfellows. One is agile and quick, the other slow moving and pensive; one obsessed with looking forward, the other struggling to keep up with its past.

And yet, it’s true. Apple, IBM, Microsoft, Samsung and Uber have all flirted with healthcare in recent years, from data-collecting health apps and devices to a digital cab-hailing service for medical patients. Two of the most intriguing companies to make movements around healthcare recently, though, are Amazon and Alphabet. Both of them seem to have health insurance, in particular, set in their sights.

A is for: Alphabet, Amazon or Apple

Alphabet is currently the most active investor among large tech companies in U.S. healthcare, according to CB Insights. Via Verily, an Alphabet subsidiary that focuses on using technology to better understand health, and DeepMind, another Alphabet acquisition that deals in artificial intelligence solutions, the tech giant has been exploring how to use AI to tackle disease by using data generation, detection and positive lifestyle modifications. Alphabet has also made substantial investments in Oscar, Clover and Collective Health — companies that all have their eye on disrupting the health insurance sector.

Meanwhile, Amazon raised eyebrows by making its biggest move into healthcare last summer, when it acquired the internet pharmacy startup PillPack. Then, in October 2018, it filed a patent for its Alexa voice assistant to detect colds and coughs. Furthermore, the e-commerce business has been working on an internal project named Hera, which involves using data from electronic medical records (EMRs) to identify incorrect misdiagnoses. And in January of last year, Amazon announced a partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan for an employer health initiative — a thinly veiled tactic to better understand health insurance by using workers as beta-testers with an eye toward expanding into a public market further down the line.

Apple isn’t standing by quietly, either. It was recently announced that they’ve been working with Aetna since 2016 to provide incentives for healthy behavior to their customers through personalized exercise and health tips.

While all three are making strides in the healthcare industry, health insurance, in particular, seems like it may to be a major part of their long-term strategy for Alphabet and Amazon.

Can the tech giants cross the moat?

This isn’t the first time tech-savvy businesses have sized up the U..S healthcare and health insurance industries. They’ve been viewed as sitting ducks for disruption for many years. Unsurprisingly so, too. With their analogue systems, complex strata of silos and out-of-date technology, anyone would think they were primed and ready for digital disruption — that new technologies could help these out-of-date, yet highly lucrative industries, become more streamlined, efficient and customer-centric.

That’s what Better — a mobile experience for healthcare — thought when it was launched in 2013 by Health Hero co-founder and Rock Health mentor, Geoffrey Clapp. The startup struggled from day one with investments and the seemingly monumental task of applying a simple solution to a plethora of problems. Better admitted defeat just two years after it launched.

“We were doing concierge services across all disease states, across anatomic states like a knee surgery or a stroke, and at the same time doing bundled payment services and multiple, different payment structures,” Clapp said in 2016, when looking back at Better. “People may love the product, but they want it to address whatever problem theirs might be. And we talked ourselves into thinking we would have verticals.”

Health insurance is just as difficult a sector to disrupt as other areas of the U.S. healthcare industry, but is less appealing to startups due to the large resources companies need to have before they even enter the market.

Despite their size, capital and ingenuity, making inroads into the healthcare industry won’t be easy for tech companies.

An interesting case study over the past few years has been Oscar Health (which, incidentally, received $375 million in investment from Alphabet last year). Launched in 2012 under the proviso of using technology and customer experience insight to simplify health insurance, Oscar is often seen as the poster-boy of startups disrupting health insurance. However, its journey has been anything but smooth and, despite significant investment, its future is anything but clear.

The company has struggled to compete in the market for individual healthcare, as well as assembling the necessary network of doctors and hospitals. And while Oscar recorded its first profitable quarter in its now seven-year lifespan in 2018, it has a history of hemorrhaging money, including more than $200 million in losses in 2016. If Oscar is the success story of startups disrupting U.S. health insurance, then it’s a stark reminder as to how much of an uphill battle that is.

Of course, Amazon and Alphabet don’t have to worry about losing money in their long-term game plan for health insurance. But they still have to overcome the long list of regulations and pragmatisms that can’t simply be overcome by throwing money at the problem. They won’t automatically succeed on account of their size and resources, as Google learned when it closed the doors of Google Health in 2012, citing that the service “is not having the broad impact that we hoped it would.”

It seems that Alphabet, Amazon et al. have learned from their mistakes, the mistakes of their peers and those of startups like Better. Alphabet isn’t diving in head-first this time around. Instead, it’s tackling specific diseases, partnering with hospitals and applying its vast know-how in AI to combat real problems that affect millions of Americans. And Amazon — via its partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan — is taking the time to better understand the market it hopes to disrupt by taking a close look at its problems on a micro scale.

Grow or die

If the U.S. health insurance industry is indeed so difficult to conquer, it begs the question as to why tech companies are taking another swing at it. The simple answer is revenue.

The U.S. health insurance net premiums recorded by life/health insurers in 2017 totaled $594.9 billion. That’s more than three times Amazon’s 2017 revenue ($178 billion) and more than times that of Alphabet’s ($111 billion).

There’s more to it.

When a business’ annual revenue exceeds $100 billion, it’s sufficiently difficult to find new avenues of meaningful growth. This is problematic for companies like Alphabet and Amazon. Growth and scale are vital for them. Without them, the vultures begin to circle, believing that they’re losing their grip on their ecosystems — and with that, stock prices take a hit.

We’ve already seen the tech giants mitigate this risk by successfully expanding into other verticals in recent years. Whether it’s grocery delivery services, voice assistants or self-driving cars, tech businesses are constantly looking to expand their empires to fresh verticals. Healthcare is simply the next industry to be re-conquered.

Roadblocks along the way

Despite their size, capital and ingenuity, making inroads into the healthcare industry won’t be easy for tech companies, no matter how carefully they approach it. While they may seem to be old hands when it comes to disrupting industries, healthcare and health insurance are different beasts entirely.

For a start, there’s regulation. In order to sell and distribute drugs, there are complex and expensive hoops to be jumped through, overseen by regulatory bodies, including the FDA and the DEA.

There’s always been a question mark over how these companies use the vast swathes of data available to them.

Then there’s data and privacy. Tech giants may believe that technology gives them an upper-hand over the industry’s long-standing incumbents, but tech solutions require access to data that’s also regulated by strict privacy laws — a major barrier to be overcome for those looking to enter specifically into health insurance.

And on top of all of that, the tech companies looking to take on the health insurance would have to navigate the state-based insurance regulatory system. What works in Utah, which is generally regarded as a more lenient state when it come to insurance regulation, may not work in California, which is seen as one of the strictest states.

Privacy, data and universal healthcare

While there may be challenges facing new businesses in becoming major players in the health insurance industry, it would take a brave person to bet against them. If they were to succeed, some of the ramifications might not be appealing to everyone.

For a start, there’s always been a question mark over how these companies use the vast swathes of data available to them. Tech companies have been rocked in recent years by the public turning against them over how their data is used to turn a profit. But what if that data was used to calculate a customer’s insurance premium? It’s feasible that a user’s premium could go down if data shows they live a healthy lifestyle; for instance, they purchase healthy foods, have a gym a membership and track regular workouts through a device.

On the other hand, inactive users shown to buy unhealthy foods and products could see their premiums go up over time.

It’s a genuine concern according to Peter Swire, a privacy expert at the Scheller College of Business at Georgia Tech and the White House coordinator for the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy rule under President Clinton. “As far as I can tell, the Amazon website could use its information about the customer to inform its health insurance affiliate about the customer,” Swire says in an interview with Vice. “In other words, I’m not aware of rules that stop data from outside the healthcare system from being used by the health insurance company.”

Tangent: Will tech companies push against a single-payer or universal healthcare system?

I’ll pause a moment to put on my tinfoil hat.

As recently as 2017, Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini stated he’d be open to discussing a single-payer system, “Single-payer, I think we should have that debate as a nation.”

Single-payer or Medicare-for-all are both in the sights of progressive Democrats in Washington. Those fighting for a single-payer health system in the model of countries like the U.K. and Canada are already up against powerful lobbying groups from pharmaceutical and insurance industries. Game theory may tell us that adding the richest companies in the world to that group would surely push the idea of universal healthcare in the U.S. further away from reality.

This is a big, “what if” scenario that plagues me as we consider a future where the tech companies begin to create their own insurance solutions. They definitely would not want the government to come in and replace private insurance.

Let’s remove the tinfoil hat and we can return to the less conspiracy theory-themed conversation.

Better than the status quo

Of course, there’s no evidence to suggest that Amazon, Google or any other tech giant interested in exploring health insurance might use data against its users or lobby against universal healthcare. In fact, if there’s one thing these businesses know, it’s the importance of pleasing as many people as possible. They’re aware, often from personal experience, how damaging negative publicity can be — not just to a particular product or service, but to the whole business. Following nefarious money-making initiatives could destroy any hope of disrupting the health insurance industry before they’ve even begun.

We could imagine that tech companies would approach their solution with their special sauce.

Amazon may bring extreme efficiency, no frills and incredibly fast logistics to their offering. Google or an Alphabet company may come from an AI and predictive approach, wherein every person would have a health assistant backed by a field of specialists. Alphabet machines and kiosks you could drop into for a quick health check. Apple would bring their polished retail experience and love of control to create a vertical solution like what we see from Kaiser Permanente. They’d work to ensure the quality of the experience. Each company would, effectively, serve a different type of consumer.

If they decide to show their hand and go head-to-head with the health insurance industry’s current incumbents, they may do so by positioning themselves as the benevolent alternative that works for everyone in the system and is ultimately better, less expensive and more efficient. According to a 2017 McKinsey study, very few insurers are providing what the American people want from their providers, namely convenience, more incorporated technology, tools that promote health and wellness and greater value for the money.

These are areas where technologists often excel: providing high levels of customer care, improving services and driving down cost, and doing so by incorporating cutting-edge technology. If they can do that with health insurance, then they may well be within a shot of finally delivering on technology’s promise to disrupt an out-of-date industry.

Growth is the lifeblood of these companies, and the health vertical that is ripe for disruption is, coincidentally, vital to our survival. It’s going to be a fascinating battle when it plays out to see whether, like Uber’s cowboy start, tech companies can leapfrog regulation and force the hand of the legislatures with the help of consumer demand.

source https://techcrunch.com/2019/01/31/will-tech-companies-change-the-way-we-manage-our-health/

0 notes

Text

Will tech companies change the way we manage our health?

Cyrus Radfar Contributor

Cyrus Radfar is the founding partner at V1 Worldwide.

More posts by this contributor

Amazon isn’t to blame for the Postal Service’s woes, but it will need to innovate to survive

Dear United: Autonomous cars will pull you out of your seat

As of September 2018, the top 10 tech companies in the U.S. had spent a total of $4.7 billion on healthcare acquisitions since 2012. The number of healthcare deals undertaken by those companies has consistently risen year-on-year. It all points to an increasing interest from technology companies in U.S. healthcare, which raises many questions as to what their intentions are, and what the ramifications will be for the health industry.

It also begs the question as to why healthcare has become the latest target of U.S. tech giants. On the surface, they don’t seem like natural bedfellows. One is agile and quick, the other slow moving and pensive; one obsessed with looking forward, the other struggling to keep up with its past.

And yet, it’s true. Apple, IBM, Microsoft, Samsung and Uber have all flirted with healthcare in recent years, from data-collecting health apps and devices to a digital cab-hailing service for medical patients. Two of the most intriguing companies to make movements around healthcare recently, though, are Amazon and Alphabet. Both of them seem to have health insurance, in particular, set in their sights.

A is for: Alphabet, Amazon or Apple

Alphabet is currently the most active investor among large tech companies in U.S. healthcare, according to CB Insights. Via Verily, an Alphabet subsidiary that focuses on using technology to better understand health, and DeepMind, another Alphabet acquisition that deals in artificial intelligence solutions, the tech giant has been exploring how to use AI to tackle disease by using data generation, detection and positive lifestyle modifications. Alphabet has also made substantial investments in Oscar, Clover and Collective Health — companies that all have their eye on disrupting the health insurance sector.

Meanwhile, Amazon raised eyebrows by making its biggest move into healthcare last summer, when it acquired the internet pharmacy startup PillPack. Then, in October 2018, it filed a patent for its Alexa voice assistant to detect colds and coughs. Furthermore, the e-commerce business has been working on an internal project named Hera, which involves using data from electronic medical records (EMRs) to identify incorrect misdiagnoses. And in January of last year, Amazon announced a partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan for an employer health initiative — a thinly veiled tactic to better understand health insurance by using workers as beta-testers with an eye toward expanding into a public market further down the line.

Apple isn’t standing by quietly, either. It was recently announced that they’ve been working with Aetna since 2016 to provide incentives for healthy behavior to their customers through personalized exercise and health tips.

While all three are making strides in the healthcare industry, health insurance, in particular, seems like it may to be a major part of their long-term strategy for Alphabet and Amazon.

Can the tech giants cross the moat?

This isn’t the first time tech-savvy businesses have sized up the U..S healthcare and health insurance industries. They’ve been viewed as sitting ducks for disruption for many years. Unsurprisingly so, too. With their analogue systems, complex strata of silos and out-of-date technology, anyone would think they were primed and ready for digital disruption — that new technologies could help these out-of-date, yet highly lucrative industries, become more streamlined, efficient and customer-centric.

That’s what Better — a mobile experience for healthcare — thought when it was launched in 2013 by Health Hero co-founder and Rock Health mentor, Geoffrey Clapp. The startup struggled from day one with investments and the seemingly monumental task of applying a simple solution to a plethora of problems. Better admitted defeat just two years after it launched.

“We were doing concierge services across all disease states, across anatomic states like a knee surgery or a stroke, and at the same time doing bundled payment services and multiple, different payment structures,” Clapp said in 2016, when looking back at Better. “People may love the product, but they want it to address whatever problem theirs might be. And we talked ourselves into thinking we would have verticals.”

Health insurance is just as difficult a sector to disrupt as other areas of the U.S. healthcare industry, but is less appealing to startups due to the large resources companies need to have before they even enter the market.

Despite their size, capital and ingenuity, making inroads into the healthcare industry won’t be easy for tech companies.

An interesting case study over the past few years has been Oscar Health (which, incidentally, received $375 million in investment from Alphabet last year). Launched in 2012 under the proviso of using technology and customer experience insight to simplify health insurance, Oscar is often seen as the poster-boy of startups disrupting health insurance. However, its journey has been anything but smooth and, despite significant investment, its future is anything but clear.

The company has struggled to compete in the market for individual healthcare, as well as assembling the necessary network of doctors and hospitals. And while Oscar recorded its first profitable quarter in its now seven-year lifespan in 2018, it has a history of hemorrhaging money, including more than $200 million in losses in 2016. If Oscar is the success story of startups disrupting U.S. health insurance, then it’s a stark reminder as to how much of an uphill battle that is.

Of course, Amazon and Alphabet don’t have to worry about losing money in their long-term game plan for health insurance. But they still have to overcome the long list of regulations and pragmatisms that can’t simply be overcome by throwing money at the problem. They won’t automatically succeed on account of their size and resources, as Google learned when it closed the doors of Google Health in 2012, citing that the service “is not having the broad impact that we hoped it would.”

It seems that Alphabet, Amazon et al. have learned from their mistakes, the mistakes of their peers and those of startups like Better. Alphabet isn’t diving in head-first this time around. Instead, it’s tackling specific diseases, partnering with hospitals and applying its vast know-how in AI to combat real problems that affect millions of Americans. And Amazon — via its partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan — is taking the time to better understand the market it hopes to disrupt by taking a close look at its problems on a micro scale.

Grow or die

If the U.S. health insurance industry is indeed so difficult to conquer, it begs the question as to why tech companies are taking another swing at it. The simple answer is revenue.

The U.S. health insurance net premiums recorded by life/health insurers in 2017 totaled $594.9 billion. That’s more than three times Amazon’s 2017 revenue ($178 billion) and more than times that of Alphabet’s ($111 billion).

There’s more to it.

When a business’ annual revenue exceeds $100 billion, it’s sufficiently difficult to find new avenues of meaningful growth. This is problematic for companies like Alphabet and Amazon. Growth and scale are vital for them. Without them, the vultures begin to circle, believing that they’re losing their grip on their ecosystems — and with that, stock prices take a hit.

We’ve already seen the tech giants mitigate this risk by successfully expanding into other verticals in recent years. Whether it’s grocery delivery services, voice assistants or self-driving cars, tech businesses are constantly looking to expand their empires to fresh verticals. Healthcare is simply the next industry to be re-conquered.

Roadblocks along the way

Despite their size, capital and ingenuity, making inroads into the healthcare industry won’t be easy for tech companies, no matter how carefully they approach it. While they may seem to be old hands when it comes to disrupting industries, healthcare and health insurance are different beasts entirely.

For a start, there’s regulation. In order to sell and distribute drugs, there are complex and expensive hoops to be jumped through, overseen by regulatory bodies, including the FDA and the DEA.

There’s always been a question mark over how these companies use the vast swathes of data available to them.

Then there’s data and privacy. Tech giants may believe that technology gives them an upper-hand over the industry’s long-standing incumbents, but tech solutions require access to data that’s also regulated by strict privacy laws — a major barrier to be overcome for those looking to enter specifically into health insurance.

And on top of all of that, the tech companies looking to take on the health insurance would have to navigate the state-based insurance regulatory system. What works in Utah, which is generally regarded as a more lenient state when it come to insurance regulation, may not work in California, which is seen as one of the strictest states.

Privacy, data and universal healthcare

While there may be challenges facing new businesses in becoming major players in the health insurance industry, it would take a brave person to bet against them. If they were to succeed, some of the ramifications might not be appealing to everyone.

For a start, there’s always been a question mark over how these companies use the vast swathes of data available to them. Tech companies have been rocked in recent years by the public turning against them over how their data is used to turn a profit. But what if that data was used to calculate a customer’s insurance premium? It’s feasible that a user’s premium could go down if data shows they live a healthy lifestyle; for instance, they purchase healthy foods, have a gym a membership and track regular workouts through a device.

On the other hand, inactive users shown to buy unhealthy foods and products could see their premiums go up over time.

It’s a genuine concern according to Peter Swire, a privacy expert at the Scheller College of Business at Georgia Tech and the White House coordinator for the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy rule under President Clinton. “As far as I can tell, the Amazon website could use its information about the customer to inform its health insurance affiliate about the customer,” Swire says in an interview with Vice. “In other words, I’m not aware of rules that stop data from outside the healthcare system from being used by the health insurance company.”

Tangent: Will tech companies push against a single-payer or universal healthcare system?

I’ll pause a moment to put on my tinfoil hat.

As recently as 2017, Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini stated he’d be open to discussing a single-payer system, “Single-payer, I think we should have that debate as a nation.”

Single-payer or Medicare-for-all are both in the sights of progressive Democrats in Washington. Those fighting for a single-payer health system in the model of countries like the U.K. and Canada are already up against powerful lobbying groups from pharmaceutical and insurance industries. Game theory may tell us that adding the richest companies in the world to that group would surely push the idea of universal healthcare in the U.S. further away from reality.

This is a big, “what if” scenario that plagues me as we consider a future where the tech companies begin to create their own insurance solutions. They definitely would not want the government to come in and replace private insurance.

Let’s remove the tinfoil hat and we can return to the less conspiracy theory-themed conversation.

Better than the status quo

Of course, there’s no evidence to suggest that Amazon, Google or any other tech giant interested in exploring health insurance might use data against its users or lobby against universal healthcare. In fact, if there’s one thing these businesses know, it’s the importance of pleasing as many people as possible. They’re aware, often from personal experience, how damaging negative publicity can be — not just to a particular product or service, but to the whole business. Following nefarious money-making initiatives could destroy any hope of disrupting the health insurance industry before they’ve even begun.

We could imagine that tech companies would approach their solution with their special sauce.

Amazon may bring extreme efficiency, no frills and incredibly fast logistics to their offering. Google or an Alphabet company may come from an AI and predictive approach, wherein every person would have a health assistant backed by a field of specialists. Alphabet machines and kiosks you could drop into for a quick health check. Apple would bring their polished retail experience and love of control to create a vertical solution like what we see from Kaiser Permanente. They’d work to ensure the quality of the experience. Each company would, effectively, serve a different type of consumer.

If they decide to show their hand and go head-to-head with the health insurance industry’s current incumbents, they may do so by positioning themselves as the benevolent alternative that works for everyone in the system and is ultimately better, less expensive and more efficient. According to a 2017 McKinsey study, very few insurers are providing what the American people want from their providers, namely convenience, more incorporated technology, tools that promote health and wellness and greater value for the money.

These are areas where technologists often excel: providing high levels of customer care, improving services and driving down cost, and doing so by incorporating cutting-edge technology. If they can do that with health insurance, then they may well be within a shot of finally delivering on technology’s promise to disrupt an out-of-date industry.

Growth is the lifeblood of these companies, and the health vertical that is ripe for disruption is, coincidentally, vital to our survival. It’s going to be a fascinating battle when it plays out to see whether, like Uber’s cowboy start, tech companies can leapfrog regulation and force the hand of the legislatures with the help of consumer demand.

Via David Riggs https://techcrunch.com

0 notes

Text

The Washington Post Endorses Portman’s Bipartisan STOP Act

The Washington Post editorial board endorsed Senator Portman’s Synthetics Trafficking and Overdose Prevention (STOP) Act, bipartisan legislation that will help prevent the shipment of synthetic opioids like fentanyl into the United States through the Postal Service. The House passed the bill last week by an overwhelming bipartisan margin, and Portman delivered remarks on the Senate floor calling on the Senate to follow suit.

The full editorial can be found below and at this link.

Opioids Come From China in the U.S. Mail. Here’s How to Stop it.

By Washington Post Editorial Board, June 16

Like all drug scourges, the fentanyl epidemic that claims so many lives every day is a matter of supply and demand. The demand, alas, is made in America. The supply, by contrast, is overwhelmingly imported, with a key source being China, where a poorly regulated cottage industry makes the stuff, takes orders over the Internet and ships it via international mail to the United States, Canada and Mexico.

Increased prevention and treatment efforts can curb demand; but it’s going to take more enforcement to disrupt the supply chain. That’s much easier said than done, and would be even if China’s regulatory system were not fragmented and corrupt. Still, authorities on the U.S. side could benefit from a more sophisticated set of tools, which brings us to the good news from Capitol Hill. Yes, good news: Bipartisan legislation that is designed to plug a legal loophole that fentanyl traffickers have exploited for too long is moving toward passage.

A 2002 federal law requires private shippers such as UPS and FedEx to obtain advanced electronic data, or AED, including the names and addresses of senders and recipients on packages, plus details about the parcels’ contents. This facilitates screening and identification, ultimately deterring drug suppliers abroad. But the U.S. Postal Service, which receives 340 million packages from abroad annually, is still exempt. This had to do with the costs of compliance for the financially troubled Postal Service and the potential for conflict with other nations’ postal systems. As of 2017, the United States had persuaded counterparts abroad to supply AED on more than 40 percent of mail entering the United States, but that mostly reflected enhanced cooperation from Europe and Canada, not China.

Meanwhile, the crisis and loss of life in this country worsened. Wisely, President Trump’s commission on the opioid crisis recommended expanded use of AED, and a bill the House just passed would enact that recommendation. The so-called Stop Act, backed by lawmakers from some of the states hardest hit by the fentanyl epidemic, including Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio), would require the Postal Service to obtain AED on international mail shipments and transmit it to Customs and Border Patrol on at least 70 percent of international mail arriving to the United States by Dec. 31 and 100 percent by Dec. 31, 2020. Importantly, the Postal Service must refuse shipments for which AED is not furnished. As a sweetener to the Postal Service, in deference to its admitted financial woes, the bill would not require it to pay U.S. customs the same fee as private shipping services until 2020, and then only on a small minority of total imported parcels.

Sens. Orrin G. Hatch (R-Utah) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) are prepared to shepherd a bill through the Senate next, so a presidential signing ceremony could take place this summer. Stop Act or no, the nub of the matter is still China’s inability or unwillingness to crack down on production of fentanyl and fentanyl precursor chemicals — which would certainly be a better use of its repressive apparatus than, say, jailing dissidents. It sounds like the stuff of a high-level conversation between Mr. Trump and his new friend President Xi Jinping.

###

from Rob Portman http://www.portman.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ContentRecord_id=DC0F695C-D335-40A6-8EE4-0CAC1976774F

0 notes

Text

Amazon isn’t to blame for the Postal Service’s woes, but it will need to innovate to survive

Buy some great High Tech products from WithCharity.org #All Profits go to Charity

Cyrus Radfar

Contributor

Cyrus Radfar is a founding engineer of AddThis, which was acquired by Oracle.

More posts by this contributor

Dear United: Autonomous cars will pull you out of your seat

With autonomy, commercial real estate could go mobile

In the past week, the 45th president has Twit-tacked Amazon three times and, potentially, cost their shareholders over $40 billion in market cap or just more than one Greek economy.

At the heart of our current President’s criticism is a claim that Amazon is making a mint and leaving a *failing* U.S. Postal Service holding the bag. It’s not a new critique from the Twitterer-in-Chief, but it is one that’s worth unpacking given the crippling effect technologies have had on the USPS — where email is even more reliable than a carrier undeterred by “snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night.“

Is it failing?

“Why is the United States Post Office, which is losing many billions of dollars a year, while charging Amazon and others so little to deliver their packages, making Amazon richer and the Post Office dumber and poorer?” This infantile question was posed by President Trump on Twitter in December 2017. While it’s not clear what exactly prompted Trump’s criticism, the tweet did spark a wave of debate as to whether the Postal Service is indeed failing and, if so, whether Amazon is to blame.

First of all, it’s true that the Postal Service is “losing billions of dollars a year” – $2.7 billion in 2017, to be more precise. In fact, the Postal Service has been losing money for over a decade. And the USPS does have a curious relationship with Amazon. While competitors UPS and FedEx charge the e-commerce giant $7-$8 per package, USPS only charges for $2 for the service. However, as with most stories, that of USPS is more complicated.

USPS and Amazon

The USPS-Amazon relationship may be seen as “dumb” by the 45th president, but to many it’s a piece of shrewd business on the part of the Postal Service. As of 2017, Amazon was USPS’s biggest customer, and an intelligent way for the independent agency – that traditionally made its money by having a monopoly on first class mail – to get a piece of the increasingly profitable package delivery pie. It’s not the first time that the Postal Service has tried to muscle its way in on the growing package delivery industry. Back in 2010, the entertainment company Netflix accounted for $600 million from its DVD subscription service. Of course, the Netflix DVD delivery service is fast fading and being replaced by on-demand streaming; and Amazon look to be preparing their own delivery service. It seems that the USPS may have to prepare itself to be jolted by another wave of disruption.

One-Two Punch of Email and a Financial Crisis

The Postal Service’s first major battle against the age of innovation came with the rise of email, and it didn’t take the beating that you might expect. Despite the fact that in 2002 the majority of Americans used email, the Postal Service still managed to make profit between 2003 and 2006. During this time, people were still writing letters, sending greetings cards and, perhaps most importantly, bills were still sent by post.

It wasn’t until the 2007 global financial crisis that the Postal Service took a hit that, arguably, it still hasn’t recovered from. After thousands of businesses suffered from the crisis, they started to cut back on expenses wherever possible, and one such place was mail. Back in 2000, nearly two-thirds of bills were delivered by USPS, and the total revenue from bill payments in this year was estimated at between $15 and $18 billion. Between 2006 and 2010, USPS volume fell by 42 billions pieces, with 15 billion of those being caused by electronic billing.

And if that weren’t enough, the rise of social media further confounded USPS’s problems. Between 2010 and 2014, postcard volume fell by 430 million. As more and more people began logging into Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat to send virtual Christmas cards and birthday wishes, fewer people were sending mail, and therefore fewer profits for the agency that had had its fair share of knocks in the 21st century.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/André-Pierre du Plessis

Innovating within a Risk-Averse Government

To suggest that those in charge at the Postal Service have been idly watching as new technologies disrupt and threaten the agency would be unfair.

It is an organization that looks to engage with the latest technology. For instance, in 2014, it released a white paper on the impact that 3D printing could have on the industry and how the Postal Service could benefit; and again in 2015 it released another on the Internet of Things. Both papers were clearly commissioned with a degree of prescience, being published before either technology had begun to pervade the public consciousness.

Unfortunately, though, forward-thinking initiatives such as these have been blocked before they can enter the action stage. USPS’s status as a quasi government entity may have its benefits, such as a monopoly on all first class post, but in return Congress has a say in how the agency is run. It can outline the products and services provided by the Postal Service, and set its prices. However, unlike other Federal agencies, USPS receives no funding, and hasn’t done since 1982.