#jerking it postmodern style

Photo

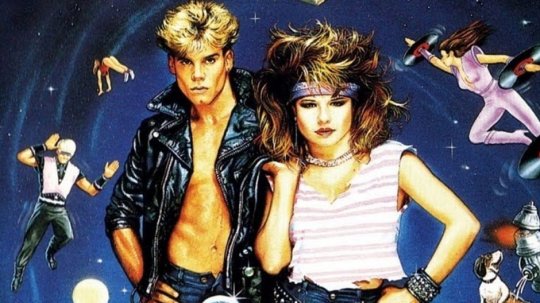

Recently watched: Voyage of the Rock Aliens (1984). Tagline: “the story of a guy, a girl and an alien... and one night they will always remember!” I’m using this period of enforced social isolation to explore the weirder corners of YouTube for long forgotten and obscure movies. (My boyfriend is accompanying me only semi-willingly).

Incomprehensible. Stultifying. Bizarre. Botched! In the early eighties, former child actress, cherub-faced starlet and “triple threat” Pia Zadora reigned as the undisputed queen of bad movies. (Her filmography-from-hell includes crimes-against-cinema like Fake-out (1982) and The Lonely Lady (1983)). Enduring the 97-minute duration of misbegotten low-budget New Wave musical comedy Voyage of the Rock Aliens certainly justifies how Zadora earned that title. (Note: don’t confuse Voyage of the Rock Aliens with Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women (1968) – an entirely different but equally terrible film starring that earlier queen of bad movies, Mamie Van Doren).

Voyage was calculatedly formulated to promote Zadora as a viable pop siren in the vein of Madonna or Cyndi Lauper. In fact, it opens with an epic rock video for “When the Rain Begins to Fall”, Zadora’s hi-NRG disco duet with Jermaine Jackson. The video has that artfully distressed post-apocalyptic / post-punk look typical of the era (it’s hard to overstate the stylistic influence of Mad Max in the eighties). Seemingly tacked-on at random, the video bears zero relation to what unfolds next. How to explain Voyage of the Rock Aliens? According to Wikipedia, its scriptwriter conceived it as a deliberately campy tongue-in-cheek spoof hybrid of fifties and sixties b-movie genres. A postmodern mash-up of science fiction, beach party musicals, monster movies and rock’n’roll juvenile delinquent flicks sounds potentially amusing in more competent hands, but the conception and execution here is frankly - if cheerfully - inept.

Zany hijinks, wacky misunderstandings and “what-the-fuck” moments ensue when a group of rock’n’roll-crazed aliens (styled to vaguely resemble Devo) land their guitar-shaped spaceship on earth and try to ingratiate themselves with the local teenagers of a town called Speelburg. Voyage’s tone is established with an introductory Beach Blanket Bingo-style musical number. The song is grating. The choreography is clunky. The weather is visibly overcast and chilly. Some of the “high schoolers” are seemingly well into their late twenties. To be fair, it does offer a time capsule of eighties fashion trends: it’s a veritable day-glo riot of ra-ra skirts, crimped hair, fingerless lace gloves and wraparound sunglasses. Dee Dee (Zadora) yearns to sing with her boyfriend Frankie’s band (Frankie and The Pack) at their high school’s upcoming cotillion. But surly delinquent hoodlum Frankie (Craig Sheffer) is such a selfish, insecure jerk he won’t let her. (This scenario reminded me of Lucy constantly wanting to crash Ricky’s stage show in old episodes of I Love Lucy). The leader of the aliens (Tom Nolan) develops a crush on Dee Dee and has no qualms about her joining his band, inciting Frankie’s jealousy.

Proceedings are padded-out with some annoying sub-plots. Two homicidal killers escape from a high security mental facility. The eccentric elderly female sheriff investigates the town’s UFO sighting. (This surely represents an unseemly career low for Academy Award-winning veteran character actress Ruth Gordon of Rosemary’s Baby and Harold and Maude fame). There’s also a sea monster whose tentacle pops up at random and is never explained. Storytelling coherence isn’t one of Voyage’s strengths: it frequently feels like some pages have gone missing from the script, or some crucial explanatory scenes have been accidentally deleted.

Anyway, Zadora gamely tackles the acting, singing and dancing with more enthusiasm than skill. Frankie’s bandmates are played by a genuine Los Angeles psychobilly band called Jimmy and The Mustangs - a poor man’s Stray Cats, although it must be said they do provide eye candy in their mesh t-shirts and studded leather biker jackets. Speaking of which: pouting young pretty boy Craig Sheffer’s Frankie is filmed like an escapee from an eighties gay porn film, with a homoerotic focus on his sinewy torso and painted-on black jeans. With horrible symmetry, Voyage concludes by reprising “When the Rain Begins to Fall” (with Scheffer lip-syncing to Jermaine Jackson’s vocals) with some of the most half-assed green screen technology ever captured on celluloid. Clearly the filmmakers had stopped caring by then. Problem is, you will have too!

Voyage of the Rock Aliens is FREE to view on Amazon Prime. Watch the trailer here.

#pia zadora#voyage of the rock aliens#bad movies we love#bad movies for bad people#cult cinema#cult film#kitsch

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the fanfic ask game! :)

F, G, J, M, R, T

F: Share a snippet from one of your favorite dialogue scenes you’ve written and explain why you’re proud of it.

One of my favourite moments comes from the Steve and Bucky interaction in the start of Not My Type, But She’s So Right:

Bucky chucks a pillow at Steve’s face. “She’s not my type. She’s full of energy, dramatic, and wants to end up on Broadway someday. She swoons over guys with great singing voices and I can’t carry a tune in a bucket. If I ask out this girl, then you can ask out your girl.”

“You know what you’re doing. I… girls aren’t exactly lining up to date a guy they could step on, you know?”

“There are some girls who like stepping on-”

“I hate you sometimes.”

“You know you love me, Steve.” Bucky sticks his tongue out. “Anyway, if you ask out the girl that you have a crush on, I’ll ask out the girl that I have a crush on. Do we have a deal?”

This exchange worried me at the time. I almost backed out of publishing it. This fic is Steve/Peggy. Steve/Bucky shippers and Steve/Peggy shippers can have an adversarial relationship. I was worried people would have me for having Bucky say Steve loves him (platonically). Turns out, nobody cared.

G: Do you write your story from start to finish, or do you write the scenes out of order?

Nine times out of ten, I'm writing in order.

J: Write or describe an alternative ending to [insert fic].

You didn't list a fic. I’ll pick one, and you let me know what other fic you wanted.

Royal Vision was supposed to be longer. The power was supposed to go out, with Wanda and Vision searching for each other in the dark ballroom. I couldn’t get it to work, so I dropped the idea.

M: Got any premises on the back burner that you’d care to share?

Yes! Childhood friends to lovers Steve and Peggy, in a 5+1 format.

R: Are there any writers (fanfic or otherwise) you consider an influence?

Jo and Laurie, the other two-thirds of the Steggy Extended Universe writer’s group. I’ve started writing with them recently, but it’s been a wonderful experience. We all have different styles and preferred tropes, so it’s interesting melting them together.

For non-fanfic writers, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven weaves many narratives together in a clever, engaging way, managing to jump all over the world with decade-long time jumps without ever being confusing. I’d love to write something that complex one day. House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski is pretentious, but it taught me that sometimes, the right answer to important questions the plot raises are “It doesn’t matter.” It’s been a decade since I read anything from Lemony Snicket but that style is still so good, and his work was my unwitting entry into postmodern fiction.

T: Any fandom tropes you can’t stand?

The idea that someone has tagged a fic a certain way to be mean. I know this might happen on occasion, but I think the amount of times someone has done that with good intentions outweigh people who want to be jerks online. There are no clear guidelines for what “counts” in a certain tag; it’s often up to author interpretation. I see this most often with the AO3 ship feeds on Tumblr. A person will tag a pairing because they’ve included it in their story even though it isn’t the main focus. (I’ve actually done this twice. Both the times were edge cases, and I put a note in the description explaining why I did it, so readers aren’t confused.)

If you feel like a work has been tagged incorrectly, contact the author and raise the concern politely. They might have made a mistake, or not know about other tags.

Also, if you’re posting directly to tumblr and your work is long, please include “Keep Reading” after the first couple of paragraphs! Scrolling past a very long fic is annoying.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Robicheaux-Rocks Home for Wayward Boys - Part Three

Part Three: It’s Too Late as We’re Walking By

Thanks to Postmodern Jukebox’s rendition of “Don’t Look Back in Anger” for helping to power through this. Click here to read Part One and here for Part Two.

1988

Fame came to New Orleans early, and with the city’s language, its food, its debauchery, quickly made a home. Joining in the bit of fame is New Orleans’s architecture from French Quarter balconies to narrow shotgun houses—and the cities of the dead. There are parades into and out of these cities, just as there are parades over every other inch of New Orleans, and tourists come to ogle the mourners marching. They walk amongst the crypts and mausoleums, taking pictures of the dead they’ve never known. It’s disrespectful, Goodnight thinks, but he has half a mind to pay people to take pictures of this tomb. He’ll put up banners and ribbons and holler until his throat is hoarse. He’ll turn this place into a goddamn circus, and it’ll be the respect they deserve.

How long he’s been standing in front of it, he has no idea, but it’s long enough that he’s memorized the dates of everyone interred in this Robicheaux tomb. There is Great-Grandma Georgine, who had lived a hundred years and terrorized his mother for a third of them; Great-Grandma Georgine’s husband Gaspard, who died long before he could witness her terror; Grandma Patrice, who had died from Great-Grandma Georgine’s terror; and at the bottom, most recently added, the tomb reads, Major Augustin J. Robicheaux, 1922-1986, and Varina Delacroix Robicheaux, 1935-1986.

“I feel a little duped, Mama,” Goodnight says when he finally swallows the lump in his throat because if he cries, he has no doubt that his father will come straight out of the crypt and strangle him for being such a disappointment to the Robicheaux name. Men don’t cry, and that’s the whole reason why he left in the first place, wasn’t it? To become a man? Fat lot of good it did.

“Actually, I feel very duped. You sent a kid off to war, and now here I am. Alone. Because you went and died on me, which I’m not convinced wasn’t on purpose, it’s just the sort of petty thing you would do, Mama, die when I couldn’t come to the funeral just to make me feel bad. And it’s not like you can convince me otherwise now.

“I’m done trying to please you. It’s all I ever tried to do, and look where it got me. I’m going to go to school—which is what I wanted to do, not that you ever asked—for a long time, and maybe I’ll just stay there for the rest of my life. Maybe I’ll leave when the money runs out and sleep on the streets and have mixed babies. How about that?”

Maybe it would be more satisfying if his father turned his cool, Robicheaux-blue eyes on him. Maybe it would be more satisfying if his mother brushed at imaginary flyaways and said that he would do no such common thing, her shoulders straightening as though preparing for a fight, small as she was; small women tend to be the most frightening creatures on the planet, and Goodnight has long since accepted this is due to his mother.

As it is, nothing happens. There’s no sign of his father, rigid in every sense, disdain dripping from his being, or his dainty belle of a mother to look down her dainty nose at him. Standing in front of the crypt, jabbering away to parents who couldn’t be less interested, his face red from the strain it takes to keep as impassive as possible, Goodnight can only be glad there’s no one around because he must look positively crazy.

Although, hell, he knows he is.

2006

Irish blood and Gulf Coast summers make for a roasted mess, Josh can feel it. He probably looks like a lobster, steaming and everything. No matter how much sunscreen Billy had insisted he put on before leaving the house, and even now that the sun has gone down, he can feel the heat radiating from his face, off his arms. It’ll hurt in the morning—it’s possible it already hurts now—but it’s hard to care when he’s landed on what he’s sure is an earthly heaven.

Punctuated only by the announcers and the occasional sharp crack of wooden bats, there’s a dull hum that keeps him from hearing anything Billy says to him, and the guy behind him might have sloshed beer down his back, and his legs stick to the hard plastic of the seats whenever he dares try to peel them off, but he’s never seen anything half as exciting as when the guy hit the ball so hard it cracked his bat, or when the guy at the back of their field jumped high enough to catch the ball going over the wall, or when the coaches got into that fight.

It’s the greatest day of his life.

On the field, Josh watches the pitcher jerk his head once in disagreement, then once more as he settles himself for the windup. He could do that, he just knows it; not the neighborhood-style, anything-goes baseball, but this, the real thing. He could slide, he could pitch guys out, he could hit the ball over the fence. He’d be ok with permanently looking like a lobster if it meant he could play.

Knocking his against his knee, Billy draws him from his daydream and holds out his fist. Josh takes the handful of peanuts Billy offers him, and Billy returns to his task of shelling his bag instead of watching the game. He doesn’t seem to be having the greatest day of his life, but he’s being nice Billy anyway, so it’s fine. At least he’s getting peanuts out of it, and Billy was only too happy to go after ice cream. Twice.

“What the—do you need these,” Goodnight shouts from Josh’s other side over the booing of the crowd, shaking the glasses around his neck at the umpire, and Billy catches Josh’s eye with a smirk. Most of Billy’s amusement seems to be coming from Goodnight, who is possibly more into the game than Josh is, and who flops back into his seat and rubs the bridge of his nose with a heavy sigh, muttering under his breath. Maybe Billy’s amusement is at the wrong thing, but it isn’t unwarranted.

With another smirk at Josh, Billy reaches behind him to let his arm rest on the back of his seat, his hand finding its way to Goodnight’s neck. He doesn’t move, just keeps his arm slung across the seat and his hand on Goodnight’s neck, and Goodnight glances first at Billy, long enough to lose his frustration, then down to Josh with his crooked smile.

Josh is grinning back before he realizes what he’s doing. But whatever. They’re weird. They’re nice. He’s having a good time.

Calmer now with Billy’s hand on him, Goodnight quiets down in his seat. Josh tries not to think about it when he leans back in his own seat against Billy’s arm and waits for Billy to move it, but he doesn’t. He cracks another peanut with his free hand and passes it to Josh.

This is definitely the greatest day of his life.

“Why don’t you ever let me drive,” Goodnight asks as they turn off St. Charles onto Jackson Avenue.

“Because people here don’t believe in crosswalks and you don’t believe in brakes,” Billy says, and Goodnight harrumphs, wondering if Billy’s grudge is real or just for the sake of having one. Billy harrumphs back. “On our first date, I thought, ‘this is nice, too bad we won’t live to have another.’”

With a laugh, Goodnight settles back into his seat, folding his hands on his stomach. It’s quite possible that he hadn’t been cleared to drive yet the first day he and Billy had gone out, and it was only after he noticed Billy flattened against his seat with a grip tight enough to break the door handle that he realized Billy probably should have driven. “Fair enough on that one, but in my defense, I was only trying to impress you.”

“Oh, I was impressed by something,” Billy says, and Goodnight assumes that something was not his charisma or wit. But Billy laughs too, so easy and bright, his smile just on the charming side of goofy. He’s in a good mood. A really good mood. It suits him.

Even through the ruckus of the garage door opening and Jack’s excitement that they’re home, Josh is still knocked out when Billy turns off the car, sprawled across the backseat, his head bent at such an awkward angle that his mouth falls open. At least he’s sleeping well, which is quite the rare occurrence. And it seems like such a rare occurrence that Goodnight doesn’t want to wake him, but Billy is already focused on letting Jack into the yard, so the task falls to Goodnight. Calling Josh’s name, he bats at him as he gets out of his seat, and when that leads to no avail, he reaches into the backseat to shake him, still with no sign of waking. With a sigh that borders on more of a huff, Goodnight lays down his seat.

When he pulls Josh out, he doesn’t fully realize what he’s going, but then there’s a physical weight on his shoulder that doesn’t feel as new as it should. In fact, it feels terribly familiar, a body slung over his shoulder, even if this body is more than a hundred pounds lighter and not dying, even if he won’t walk away from this covered in blood. Goodnight tries to focus on that, on the lack of weight, on the slow and gentle breathing at his neck, on counting every step in the house on New Orlean’s Jackson Avenue where he lives with Billy, into the room that is not his room anymore. As if it ever really was.

“Nighm—om,” Josh slurs when his head hits the pillow, eyes never opening, so he isn’t awake to see Goodnight freeze, one hand still trying to tug off his shoe. He didn’t hear that. He’ll swear he didn’t hear that all the way to the tomb, except he did, and now it’s ringing his ears and closing his throat and blurring his vision. He tugs off both shoes less gracefully than he’d been trying and isn’t anywhere close to quiet when he closes the door behind him.

When Goodnight comes into the kitchen, Billy is scribbling something onto a piece of paper by the light over the stove, the home phone pressed between his ear and shoulder like he’s trying to crush it. If he notices Goodnight, he gives no indication, allowing Goodnight to wipe at his eyes so that he doesn’t see; even now, after so many years of it just being Billy in the house with him, it’s still a habit to hide that part of himself. Though it’s hard to pay much attention to that when Billy is so ensnared in his conversation. “You said Erato—yes, I know where that is...tomorrow... no, we’ll get him dinner...about seven? That’s fine.”

Setting down the pen, Billy lets out one of his inaudible sighs, eyes closed, and listens to whoever is on the other line with enough patience to make Goodnight glad there’s a telephone between them. “No, it’s fine—it’s fine. We’ll take him. Yeah. Bye.”

His eyes are still closed when he hangs up the phone, and he stays like that for a moment, elbows leaned on the counter, jaw tight, clinging to his unending control. There’s no sign of startle when he opens his eyes to find Goodnight standing in the doorway. He’d known the whole time that he was there.

“Who was that,” Goodnight asks, even though he has a sinking feeling that he already knows. There’s only one reason why they’d be talking about going to Erato Street.

“Sam,” Billy says, finally clenching his jaw tight enough to return to impassive. “Maggie’s out tomorrow.”

Goodnight nods. They’d put on a good charade for their few days, and the sudden void that’s hit is exactly what he knows Billy was afraid of. But it’ll be fine. Classes start back in a few weeks for both Josh and himself. As for Billy, he’s been frantic over finding staff to cover for him, feels like he’s abandoned them to a rush of angry summer tourists, and now he can buckle down for the endless festivals coming in the fall. It’ll be fine, but Goodnight finds himself saying, “So that’s that.”

“That’s that,” Billy repeats with no small amount of mocking.

1988

If Billy hadn’t opened his restaurant in New Orleans, he wouldn’t have had a bar. He’d rather wait tables for the entire week than serve more alcohol to drunkards, or really serve drunkards at all. The thing is, he’d opened in New Orleans, and there is no such thing as a dry restaurant in the city, so gritting his teeth and doing his best to make an old-fashioned bar as posh as possible, he’d hired a few bartenders with the idea that he’d never have to deal with it.

Except for when two are home for the summer and the others can’t come in for various reasons, and then he’s stuck at the bar he didn’t want.

So far, it’s been quiet; a Wednesday, and still too early for any real raucousness, and Billy’s shifting through the stock, thinking if his bartenders weren’t so quick and if this was more of his domain, he’d reorganize the whole thing. Still, he can’t help but rearrange the glasses so they at least fit better, which is where his attention is when a stool scrapes across the floor. He turns, just as someone is saying, “Sazerac...oh.”

Oh is right. Somehow oh has neither described a situation more aptly or been so underwhelming. In the few weeks since, Billy had all but forgotten that one incident and the man he wouldn’t be buying dinner, yet here he is, ordering a Sazerac with a finesse that seems somehow unfitting. There’s an uncomfortable beat where Billy stands stupidly in front of him and he blinks stupidly back before Billy can move, mentally repeating the recipe to himself. Ice, sugar cube, bitters; add the bourbon—no, crush the sugar first. Does it need a lemon? He adds a lemon anyway because he likes the way it looks.

Sliding the glass across the bar, the man meets Billy’s eyes with a jerk of his head. If he had been beautiful before, there isn’t a description appropriate now that the fatigues have been traded for a button-up and vest even in the height of summer, hair grown out just enough that the ends brush over his collar. Tonight, there are no tears when he takes the first sip of the New Orleans staple, but rather a lopsided smile that Billy fights the urge to turn his back on, afraid his neck is visibly burning.

“I’d say the lemon was the right touch,” he says when he lowers the glass, that lopsided smile revealing all that needs to be said about the lemon. Billy’s neck feels hot enough to set his collar on fire. “Name’s Robicheaux. Ellis—Goodnight Robicheaux.”

It comes out stuttering and uncertain, and while Billy isn’t sure whether Robicheaux is speaking to Ellis or if all of that is his name, he knows it’s wrong when he asks, “Are you sure?”

“I am, sad as it is. Goodnight Robicheaux’s my name.” And to think he thought he’d had it bad with Rocks. To think this man couldn’t make any more of an impression. Damn him; Goodnight’s a name he’d be hard-pressed to forget if he tried.

“Billy—”

“Rocks,” Goodnight finishes, and then nearly finishes his drink in the next swig, his own neck going red, sending Billy back to his stupid blinking. Is he not the only one hard-pressed to forget?

His whole life, Billy’s grabbed every passing opportunity and hoped it took him somewhere good, and for the most part, it’s worked; odd jobs bought him his way out of California, sleepless nights and too many burnt fingers gave him the right connections in New York, and connections in New York landed him in New Orleans. And his restaurant, this city—he couldn’t have asked for anything better. Now, it’s a Wednesday and quiet, still too early for a real dinner rush, not that there would be much of one since it is the middle of the week, and the only person here is someone he’d been unlikely to see again but who had remembered his name anyway.

Billy hopes he doesn’t look stereotypical when he leans against the bar.

2006

Whatever Goodnight and Billy made him put on his arms and face makes him smell like he showered in cologne and pool water.

Josh tries to ignore the smell and rubs behind Jack’s ears. The puppy lays with his head in Josh’s lap, his tail lazily thumping on the porch whenever Josh looks him in the eye, and Josh wonders if he knows this is goodbye. No more fetches or nose licks or walks around the neighborhood. He won’t watch Jack trip over his own feet and go tumbling down the stairs every day. Jack is going to stay here with Goodnight and Billy, and Josh is going home.

Maybe Goodnight and Billy will let him keep him. Except Jack would be better off here, where the food is good and the house is cool and...where Goodnight and Billy are.

With no one around except Jack—who will definitely be missed—Josh doesn’t suppress his sigh. He might miss them in a few days when his mom is making Chef Boyardee for the fourth night in a row and she hasn’t done laundry in a while, and he might even miss talking to Goodnight and Billy because his mom never has anything to say. He could tell her that he was on fire for real and probably get the same response from her as he would Jack.

At the moment, they’re waiting on Goodnight to get back from whatever errand he just had to run so that they can eat and then walk to Sucré. His mom might like Sucré. He thinks she likes sugar, not that he really knows because she never says anything and never brings any home either, but she seemed to like Dairy Queen. Maybe they can walk there one day when she isn’t busy. And maybe they can meet Goodnight and Billy there, and they’ll have Jack with them. Or something. Maybe.

At least his mom won’t be in jail anymore.

One of the things Goodnight has always loved about New Orleans is how everything blends and bleeds together; the sun has hardly risen when suits go parading into Business District offices, while one block over, the first signs of Quarter life are just beginning to stir, people creeping onto Spanish balconies to watch their part of the city come to life over the rim of a coffee mug. Now, as the car eases down the oak-lined street, the sprawling mansions fade into three-story buildings that aren’t nearly as beautiful as the Garden District, all dark brick and dim windows that overlook dead grass outside.

Goodnight’s chest fills with something heavy—or heavier. New Orleans runs through his blood and spirit; he knows there’s no leaving because of it, and he knows he’s not the only one like this. If only others could love all of New Orleans.

Though he knows this side has always been here, Goodnight tells himself it was the storm that did this, turned the city upside down and put lives on display in the streets. He and Billy had been lucky during the storm, but almost a year ago, there had been boats instead of cars going up and down the flooded streets in search of people stranded on any surface above the water.

At the moment, Billy is grinning gently into the rear-view mirror and speaking only enough to prompt Joshua onwards; he’s grinning, but Goodnight can tell by the grip on the steering wheel that it’s his brave face. And as for Goodnight—he may as well be waving down a boat from the roof. Just a few days of what could have been and isn’t.

Billy glances at him from the corner of his eye and then winds their fingers together, and Goodnight squeezes to let him know he’s hanging on. It’s not a boat, but he knows better than not to take what he gets.

“Turn here,” Billy asks, flicking on the turn signal before he has an answer.

“Yeah, sure.” At the raise of Billy’s brows in the mirror, Joshua shrugs and says, “I really haven’t known where we are for like, five miles now.”

“We’ve only gone a half,” Billy says, a smile again creeping at his lips. He glances to Goodnight, who nods, the GPS in his lap conforming the next road is the right one. And the final one.

The neighborhood is as inherently New Orleans as the Quarter itself, and as such, Goodnight loves it as much as he loves his own Jackson Avenue. But it isn’t as pretty, isn’t as careless as other parts of the city, so it goes overlooked until others want to start pointing fingers. Why are people afraid of New Orleans, why is there such a stigma? Because of places like this, they say, and Goodnight wishes he could put his old talents to use again. No, it’s because of people like you who just don’t care.

Yet as Billy brings the car to a stop Goodnight looks out his window to the beaten shotgun, he can’t help but wonder if it really, truly does matter. He had cared. Billy had cared. They had cared, and they had tried, and still they’re here.

Goodnight holds open Josh’s door while he clambers out, and it’s only when he closes the door that he realizes how tightly he’d been gripping it. Stretching his fingers, he ignores it and turns his focus to Josh and Billy, who kneels down to be on his level.

“Do you remember what we said?”

“You’ll take real good care of Jack, your numbers for home and work are on the paper, and call if I need anything.”

“What else?”

“And your door is open anytime,” Josh says after a moment’s thought, his face lighting up and bringing a subsequent smile to Billy, then Goodnight as well. Goodnight swallows hard and pretends it doesn’t hurt when Billy wraps his arms around Josh, or when the boy’s arms thread behind his neck, pretends it isn’t Billy saying goodbye because that’s something Billy never does.

Their attention is cut by the creaking of the glass door, and then a woman is standing on the front porch, barefoot, long curls gnarled. She looks older now, Goodnight notes, or perhaps not older but tired. Still though, with her wide green eyes looking like someone had just jumped at her and her arms folded tightly over her chest like she’s holding onto everything she has, all Goodnight sees is the same crying, fearful child.

“That’s my mom,” Joshua says, with less enthusiasm than Goodnight would have thought the situation warranted.

“Yes, it is,” Goodnight says, feeling rather than seeing Billy bristle like the overprotective mother hen that he is. He swallows hard again. Oh, the poor child.

With his smile plastered on precariously, Goodnight pulls his gaze away from Maggie to pass the duffel with Josh’s things to him and holds out his own arm. For all his reserve and desire for disinterest, he’s a surprisingly tactile child when he wants to be, and he presses into Goodnight’s side without hesitation.

“Make sure you give that envelope to your mom,” Goodnight says with one last pat to his shoulders, and giving a nod of his head, Josh is bouncing up the sidewalk, away from them and towards Maggie, who lets go of herself long enough to pull him close. She offers him a smile, or at least what constitutes as one from her, unconfident and unpracticed, and whatever she says makes him grin back in his goofy way.

As Maggie holds open the door, Josh slips inside, into an unlit disgrace, while she lingers on the front stoop. She looks somewhere next to Goodnight, probably to Billy where she will only bitter resolve, and finally over to Goodnight. A beat, then she offers him that same unpracticed smile that he recalls so well and raises her arm just enough for a wave.

Billy is in the car before Goodnight can raise his hand to return the gesture.

Josh supposes his mom is beautiful, and if she isn’t, she at least used to be. He figures she must have been soft at one time, with her long gold curls and trace of freckles just across her nose, a smile that can’t really be called a smile when it never passes through her eyes, and sometimes, like now, when she’s conscious and alert, she makes him think of the setting sun. While he isn’t exactly sure what constitutes old or not, Josh guesses she’s too young not to be soft. He’s never been exactly sure just how old his mom is because he’s never asked and she has a face that looks almost youthful but a way of moving that suggests an aged weariness.

She moves like that now as she goes about the kitchen, her back to him, never once turning to face him. Balancing his chair on two legs, Josh ignores that, half expecting her to turn around with perfect words once he’s finished speaking because that’s what Billy had done.

“They got a puppy named Jack that always falls down the stairs, and every time, Goody always fusses about it even though he just shakes himself off and never gets hurt. And they have like ten bedrooms and a balcony that goes all around the house, and we went to the movies like every week, and they have an ice cream store right down the street, and Billy can cook real good and he can make whatever you want, and—Mama, he can make fried chicken! He doesn’t have to buy it or anything, he can make it,” Joshua exclaims, pushing back on the table so hard that he nearly tips his chair completely over. The thud it makes returning to four legs earns him half a glance over her shoulder from Maggie.

“They’re real nice,” he says when she doesn’t make any comment. Of course she doesn’t. She never says anything.

He leans his chin into his palm and watches as she freezes suddenly. After a moment, she turns to face him, a forced, pained smile on her lips, tears falling down her cheeks just as quietly as she ever is. She nods and for once, pressing a hand to her mouth, says, “I know, baby. I know.”

For once it’s silent in the green house off Cadiz Street—or not silent, but quiet, thanks to the emptiness; Papá won’t be home for the rest of his life, probably, and at the rate they’re going, Rafael and Adrian won’t be either, which is bad enough now that Tulio is gone. Since it’s Friday and his mamá doesn’t work the weekends, Alejo assumes she’s probably in Papá’s recliner downstairs with Lingo or The $10,000 Pyramid reruns playing on the television as she watches the clock, muttering over and over, “Yo quiero buenos chicos.”

Which, with his brothers gone, leaves him with the room to himself. He and Mamá had eaten dinner and watched Jeopardy! before he’d told her he was tired and slipped upstairs to the vacant room; not that he would have minded watching the Game Show Network with her, but his book had been calling for too long now, and even on his third read, he was powerless to it.

‘“I wish it need not have happened in my time,’ said Frodo.

‘"So do I,’ said Gandalf, ‘and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”’

Go, Frodo, Alejo thinks, urging Frodo on his journey without any knowledge of what happens after the Fellowship disbands. He’d curse Tulio for only giving him the first book if he wasn’t so grateful for it.

“Besa mi culo, puto,” someone snaps from the hall, and Alejo’s blood freezes. He’d been so caught up his book that he hadn’t heard them come in. How long could he—the clock reads that it’s just now nearing nine, and they have no right to pull surprises by being home this early. Alejo scrambles for the lamp while simultaneously trying to shove his book under the pillow, and he just manages to flick the switch as the door opens; Rafael mutters something about the little bastard, and the overhead light clicks on.

When their eyes adjust, Alejo finds himself sitting on the edge of his bed while his brothers squint at him in the doorway, more out of suspicion than the light. He keeps his eyes on them, rooted in place, doing his best to keep everything to himself. Adrian is the first to move, sliding past Rafael until he stands in front of Alejo, whose heart threatens to beat so fast it shoots into his throat. They make a dangerous pair and move together as one, Rafael with only the brains to know something is amiss, but Adrian is perfectly discerning and clever enough to wield Rafael’s bulk to his advantage.

Giving his brother no break, Adrian scowls at Alejo then glances down at the pillow, wadded into ball unfit for sleeping. Alejo clenches his jaw. His emotions are never hidden, and nothing he could do would fool Adrian, who, with a catlike grin, asks, “What’re you hiding?”

“Nothing,” Alejo starts to say, but gets only half of it out before Adrian’s knocked him over and Rafael’s snatched the pillow away, his fat, stupid fingers bending the pages. “Give it back, Rafa!”

“Is this your bedtime story,” Adrian coos while Rafael sneers. “Do you want us to read it to you and tuck you in too?”

“Didn’t know you could read,” Alejo snaps back in a flash of anger, and he’d regret it if they weren’t pawing at his last birthday present from Tulio.

“Looks like our baby is finally growing a pair,” Rafael snickers. He turns for the slightest moment to laugh at Adrian, who scowls back, and Alejo takes advantage of their distraction, making a lunge for his brother no matter how hopeless he knows it is. He manages to clap Rafael upside the head, but Rafael only claps back harder. Really it’s more of a punch than a clap, and Alejo recoils as his eyes sting, jaw aching.

He looks pitiful, he knows, sitting on the bed with a scowl and tears in his eyes, failing miserably at looking mean, but it’s so much effort to be able to do even that. It’s worse now that Adrian and Rafael can run unchecked by their father and Tulio, and Alejo misses them—or he misses Tulio, at least. He misses Tulio teaching him to play the guitar and his quiet companionship, the surprise visits when Tulio actually spent the night at home, the way Tulio had said, “You’re funny, nene, but you’re all right.”

Adrian scoffs at him, then tosses the book, overshooting so that it hits the wall and falls onto the other side of the bed. El rey de Roma their mamá calls him, and Alejo never really understands it until moments like these when Adrian is standing over him with a snarl to make the devil quake and a brute squad at his heels. Rafael following suite, Adrian gives one final sneer and turns to his side of the room.

Alejo waits for him to turn off the light before he wipes his eyes and picks up the book. At least it’s still intact.

1997

Billy lets the car idle for far too long before he finally finds the strength to turn off the engine. It's just past seven on a Thursday, which means Goodnight should be home because Mondays and Thursdays are his short days at school, and Billy is finally going to face him. When he slips his key into the lock, there's a flame of comfort that he is still able to do, even though part of him says Goodnight should have changed the locks eight days ago, and that's being generous, considering Billy hasn't seen him in ten—and he's been counting.

He makes sure to make as much racket as possible as he opens the door and steps inside, waiting with his heart beating its way from his chest for Goodnight to peek around the corner to see what he could be doing. He waits for Goodnight to come around the corner and tell him, “Billy, cher, I’d really you rather didn't wake the dead in this house,” but nothing happens. He hangs his coat and turns around to a hall just as empty as when he entered.

“Goody,” he starts to call, but it dies in his throat; instead, he bites his lip and shuffles down the hall past an empty living room and office, panic rising with every footstep that echoes in the stillness. There's no one in the kitchen, no one in their bedroom, no one in that room. The house is empty and it's all Billy's fault.

Alone in the kitchen, Billy scrubs his face with his hands. He'd been ready to pass out from exhaustion before he'd left the restaurant, and now it’s as if his every sense is on hyperdrive, noting the complete silence and solitude, the kitchen that's just as pristine as they'd left it ten days ago. Alone in the kitchen, Billy looks around the room and lets the weight settle around him.

It's his fault he's alone, he knows. He’d made the suggestion, and Goodnight, ever indulgent, had bent to his wills and whims like always. Billy had wanted it because he’d wanted everything with Goodnight.

And now he has nothing.

Alone in the kitchen, Billy pulls out one of the stools at the island to sit in the silence he’s created.

The first thing Goodnight sees when he turns onto the street is Billy’s car in the driveway. He drives around the block four times, waiting to see if Billy slips out again, but the fifth time he turns down the street, he loses any control he might have. If Billy’s finally done with him, better to know sooner than to keep this up.

Billy’s coat is on the rack, and Goodnight hangs his next to it like usual. It looks nice like that, he thinks, their coats hanging side by side next to the door. He lets his fingers trail over Billy’s sleeve but resists the urge to bring it to his face. Unlike he’d expected, there’s no sound upstairs to suggest Billy is packing his things, and Goodnight thinks that maybe it’s a good sign. At least, maybe it’s a sign that Billy isn’t going to leave him alone in this goddamned house and that Goodnight won’t have to explain to Sam through the bars why he’d burned the thing to the ground.

He waits another moment, listening. If Billy isn’t upstairs, there’s only one other place he would be.

Goodnight can tell Billy knows he’s there by the way he tenses and swallows hard. There’s a dozen feet between them that might as well be an ocean. This is the part he’s been waiting ten days for, ever since Billy grew silent at the hospital. This is the part where Billy looks at him with none of the familiar affection in his eyes, no hint of a smile on his face, none of the warmth Goodnight knows him for, the part where Billy says he’s already packed up all his things and he leaves Goodnight’s coat alone on the rack and walks out the door.

But when Billy finally raises his head, so slowly it’s like he hardly has the strength to do so, his face isn’t hard, his eyes aren’t cold—they’re bloodshot and tired and watering, the corners of his mouth downturned and quivering. He opens his mouth as though to say something, but with a shake of his head, he closes it and drops his face just as quickly.

“I didn’t expect to see you,” Goodnight says and regrets the words as soon as they leave his mouth, but he’s so desperate to break the silence. Billy flinches like he’s been struck, glancing back up with a sight Goodnight thought he’d go his whole life without.

There are tears falling from Billy’s eyes, leaving streaks down his cheeks as he gasps Goodnight’s name, remaining seated on the stool with tears dripping onto the counter, and when his hands go to his eyes, desperate to hide the sight from the world as his shoulders shake, Goodnight’s own throat tightens. Ready for Billy to push him away, Goodnight moves towards Billy without realizing, but Billy moves for him too, arms outstretched, palms up, melting into Goodnight’s hold.

“I’m sorry, Goody, I’m—” And then he loses all composure, a sob cutting off his apology, his hands clutching Goodnight to him. If he’s speaking any language, it’s not one Goodnight knows.

2006

When a pair of hands land on his shoulder, Goodnight jumps hard enough that he nearly drops his coffee mug onto his lap. The deep chuckle that follows tells him who it is, as if he didn’t know from the way the hands curl around his shoulders, thumbs kneading into his back. “You walk like a cat, cher, did you know that?”

“I’ve been told. What’s this,” Billy ask with a hum, leaning closer to Goodnight’s computer. Goodnight turns his head just enough to see more than a blur of Billy, his beard hitting Billy’s cheek and making him flinch with a grin, turning to face Goodnight as well. One brow arches in question at the undoubtedly giddy expression on Goodnight’s face. “Something good?”

“Finally got the go-ahead for the New Orleans lit class I’ve been wanting,” Goodnight says. There’s a rush of satisfaction and warmth at the way Billy’s face lights up for him, and it makes him glad he’d waited to tell Billy at home instead of calling him from his office.

“For the fall?”

“Spring. Upper-level too, so it should weed out most of the hoopleheads. I’m sure it helps that there’s a new professor they can dump a few beginning comps onto, but I’d like to believe they liked how well I taught it.”

“So how many Toole quotes should I expect to hear?”

“Hey, I really don't have the time to discuss the errors of your value judgements,” Goodnight says in mock contempt as Billy lets loose an easy laugh, his head tipped back in that way that makes Goodnight want to laugh too, caught off guard that Billy, of course, retained Toole. “I have a syllabus to write, thank you very much.”

Billy quiets then, and Goodnight finally spins his desk chair to face Billy fully. Traces of laughter still linger, caught behind hesitation, and before Goodnight can take hold of the hand he reaches for, Billy says quickly, “I was thinking we could go out, just the two of us. Three Sheets has that band we liked after trivia tonight.”

“Mr. Rocks, is this a date,” Goodnight teases a little reluctantly; they’ve long since abandoned the nerves in their relationship, even after their readjustment, as Goodnight would call it, if he ever called it anything, but he can’t deny the tumble Billy sends his stomach into.

Slapping away Goodnight’s hand, Billy rolls his eyes in his amused way and says, “Not if you’re going to be smug about it, it’s not. But…we haven’t gone out alone since the beginning of summer.”

I miss you, Billy is trying to say. I miss you, and I want you, and you know I’m not good at this.

Goodnight and Billy don’t speak the same language exactly. Billy gets his French mixed up, and it was a quick discovery that Goodnight should not attempt Korean; Goodnight waxes poetic about litter in the streets, and Billy nods in appreciation. But Goodnight hears him now, and he understands.

“Give me ten minutes and we can leave,” Goodnight says, reaching for Billy’s hand again. “You’re home early enough we can walk, if you’d like.”

This time Billy curls his fingers around Goodnight’s with a smile that melts away his hesitancy.

“You drank too much tonight,” Goodnight says.

Billy steps out of their bathroom to find him sitting on Billy’s side of the bed, his feet swinging back and forth in tandem over the edge. He looks like a kid, Billy thinks, face easy and flushed. “I had one. Which you drank part of.”

“Marry me,” Goodnight says then in lieu of an appropriate response, as he does once every few months. Billy looks at him blankly and returns to the bathroom. “You want to go somewhere over the semester break, we can go to Massachusetts for the week, marry on a Wednesday, spend the rest of the week in a cottage on the cape.”

Squeezing toothpaste onto his brush, Billy tries his hardest to ignore him, but Goodnight has a knack of making himself noticed that Billy only assumes is in his blood.

After so long, they can’t call themselves casual even without a ring on their fingers. Eighteen years they’ve spent together, first bumping into each other in the apartment on Dumaine, then reviving this house where they have no earthly explanation for bumping into each other. On the busy days when Billy is short on staff, Goodnight volunteers to host on the condition that he be called the house sommelier. Billy records the grades when Goodnight gets behind. Goodnight can tell when Billy’s had a bad day by the way he walks, and Billy knows that when Goodnight asks so offhandedly if Billy still loves him, it’s only because he’s not stooped so low as to beg for the reassurance. There’s no such thing as personal space with Goodnight, not where Billy is concerned, and in comparison to their earlier outing, he’d much rather have a night spent whispering, tucked together on the couch, because sweet nothings have never meant more to anyone than they do to Goodnight.

Spitting into the sink, Billy rinses his toothbrush and wonders exactly what would change. They could hang a new certificate in their office that doesn’t mean anything in their New Orleans home. They would file their taxes together, that would be new, except Billy already does both of theirs. Otherwise, they’d still go to sleep in the same bed and wake up to each other in the morning.

When he returns, Goodnight is still sitting on the edge of the bed and swinging his feet, waiting so expectantly for an answer he should already know. Billy can’t help himself when the corners of his lips twitch. Eighteen years, and Goodnight can still make his chest tight when he looks at him. It only tightens more at the smile Goodnight gives him when Billy takes his face in his hands, then again when Goodnight pulls him closer and lets Billy catch his lips in his own. As he does once every few months, Billy sighs, “We’re already married.”

#the robicheaux-rocks home#ding dong ditch#mag7#the magnificent seven#magnificent seven#fanfic#goodnight robicheaux#billy rocks#joshua faraday#vasquez

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kingdom: Tears in the Club

Ezra Rubin (aka Kingdom) is an architect of the post-club sound—a new profile cleaved from caustic synthesizers, herky jerk percussion, and crying on the dancefloor. The melting pot of sounds he and his collaborators in Fade to Mind (Nguzunguzu, Total Freedom) and Night Slugs (Bok Bok, L-Vis 1990) offered pulled from UK garage, dancehall, and diva-driven house that still seems prescient. Rubin, in particular, helped shaped a postmodern vision of R&B alongside Kelela and Dawn Richard that’s influenced everyone from FKA twigs to Justin Bieber. Rubin was staged to make a pop crossover. His debut LP, the delightfully titled Tears in the Club, is an earnest and subdued attempt at making his panoply of sounds agreeable to a general audience.

This is immediately clear from the album’s opening moment, “What Is Love,” a collaboration with SZA. Rubin is no stranger to producing for powerhouse vocalists, but with Tears in the Club he dips his toe into the world of major label team-ups, and the result has neutered the outré aspects of his sound. On “What Is Love,” certain trademarks still pop up—vaporous synth pulses and staccato percussion—but he’s slowed down the normally breakneck pace of his music to somewhere sleepier and almost lackadaisical. In the past, Rubin’s slow jams (Dawn Richards “Paint It Blue” for example) had a seething atmosphere just bubbling beneath the surface. With SZA, that feel is gone. This is also true of some of his solo tracks. “Nurtureworld” is a confusingly out-of-focus dance track that spends most of its three minutes finding its proper footing, and the album’s title track is a defanged version of the controlled chaos he once offered.

Yet, Kingdom recovers from these missteps. “Each & Every Day,” his collaboration with Vine star Najee Daniels, adds a shot of bubblegum into his otherwise ominous productions. It resembles what Charli XCX would sound like singing over a DJ Rashad beat. His second song with SZA, “Down 4 Whatever,” benefits from the more vigorous, energetic beat Rubin provides. A solo track called “Into the Fold,” offers a picture of what pop-ified post-club music could sound like—bright whacks of drums and smokey looped vocals mingle well with more experimental elements like a dissonant hiss in the background. But his thesis statement for this album comes on a song with the Internet’s Syd, who might be the perfect vocalist for Kingdom’s attempt at a crossover style. Her slinky voice follows Kingdom’s syncopations beat for beat, and the protean, mercurial change in pace befits Syd’s ability to pitch shift on the fly. It’s a promising peek into what Kingdom could do for a radio-ready artist.

On a recent release, Vertical XL EP, Rubin filled inhuman sounds with soul, and Tears in the Club attempts to take that idea to a mass audience. One wonders if he is unintentionally softening his music for the sake of a breezier product. It’s less a statement of purpose and more of an experiment with an inconclusive hypothesis. Instead of heightening, or focusing the pandemonium he could unleash on the dancefloor, his work is denatured by a fairweather disposition. Even if he never means to, Tears in the Club is a disappointingly genteel work, from an artist known for anything but.

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Plié Meets Twerk in a Performance of Black Queer Joy

Jumatatu Poe’s “Let ‘im Move You: A Study” (2013/16) and “Let ‘im Move You: This is a Success” (2016) at ICA Philadelphia (all photos by Ryan Collerd)

PHILADELPHIA — Rihanna was blasting through the DJ’s sound system, remixed with Italian prog rock band Goblin’s soundtrack to the 1977 horror masterpiece Suspiria. Two performers emerged from the audience, clad in tiny track shorts and shredded polo shirts emblazoned with hashtag marks in pink tape. They strode onto the small, slightly raised, bare wooden stage, and the shorter one, William Robinson, raised a tin can. In carefully rhythmic, halting steps, he danced across the stage, sprinkling grits as if in sacrament. The pair moved together for a few moments, circling in a sort of shuffle, then stopped. Choreographer and dancer Jumatatu Poe addressed the audience. He noted the institutional setting, the white cube, and the majority white spectators. “I brought some black folks with me, just in case,” he said, as projected video images of around 30 black men and women appeared behind him.

The performance was Jumatatu Poe’s “Let ‘im Move You: A Study” (2013/16) and “Let ‘im Move You: This is a Success” (2016), choreographed with Jermone Donte Beacham and curated by Danielle Goldman as part of ICA Philadelphia’s Endless Shout, a multifaceted exhibition exploring performance and improvisation. In Poe’s work, movements that appeared classical, like a plié, blended seamlessly with voguing, African dance movements, and J-Sette, a tightly choreographed dance style sprung out of black Southern drill teams.

William Robinson and Jumatatu Poe in “Let ‘im Move You: A Study” (2013/16) at ICA Philadelphia

James Blake’s somber ballad “Measurements” began to play. The dancers struck a pose: left foot pointed in front, arms akimbo on the waist. Poe shifted first, pulling his legs apart, swinging his hips wildly, and grinning like a madman. Robinson followed suit, mimicking the movements a moment later, two beautiful black bodies moving in tandem. Their pumping fists and fast, swirling movements were deliberately ill-paced for the slow, melancholy music. Break dance drops, high kicks, heads pulled back in the ecstasy of a self-caress, ingratiating bows with steepled hands — each move made clear that these were performative gestures of joy. That we, the predominantly white audience, were consuming and exoticizing their bodies, as white people have consumed black bodies, for entertainment and gain, for hundreds of years.

In the postmodern cauldron of cultural references Poe draws from, J-Sette emerges as the most overtly political choice. In a 2013 interview with the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, Poe discusses his discovery of J-Sette on YouTube and his fascination with what he describes as “this huge, combustive energy in these really small spaces.” He first found videos of Beacham “dancing in the garage, the living room with the table pushed back, the kitchen sometimes, or in the bedroom, behind the bed.” The domestic scale of the choreography coupled with its eruptive gyrations had Poe considering its origins in the black South. He ruminated on the tight spaces involved with the service work that people of color in the South often do, and the emotional labor that work demands, drawing lines between it and dance through the performance of joy for others. It’s rare to see an artist smile during a performance, but Poe and Robinson were both grinning throughout, exuding a sly gaiety that that they wielded like a knife, a weapon to disarm viewers.

William Robinson and Jumatatu Poe in “Let ‘im Move You: A Study” (2013/16) at ICA Philadelphia

The music cut suddenly and sharply as the dancers continued moving in offset synchronization. Poe and Robinson broke off in separate directions. The latter affixed his hands to the wall, while the former wove through the crowd. He placed his foot on a bench, and a woman seated on it slid over to accommodate him. Both dancers leaned into the wall and twerked to a spoken rhythm: gaga-gaga-ga-ga, gaga-ga-gaga-gagaaa. They then moved back to the stage, got on the floor, entwined their legs, threw off their shirts, and jerked down their pants. Bare assed, they fitfully twerked with labored breaths as a thin keyboard organ played against the sound of a metronome, worlds away from the previous R&B remixes.

Poe and Robinson performed an iteration of the same piece last summer on a stretch of 52nd Street near Baltimore Avenue, deep in West Philly. 52nd Street was once considered the “Main Street” of West Philadelphia. It was a center for jazz, shopping, and black culture until it fell into a spiraling decline in the 1980s and ’90s, when it became better known for crime than culture. In a panel after the ICA performance, Poe described the experience of dancing there in contrast to dancing at ICA, on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania, an institution historically rife with white supremacy; he spoke of the street’s summer heat, the homophobic jeers, and pushing, pushing through the performance. That version of the piece was sans nudity, but with plenty of booty popping.

vimeo

Toward the end of the video documenting the work, a woman appears in the doorway of the Chinese restaurant they’re dancing in front of and crosses her arms disapprovingly. Everything from the grime on the sidewalk to the diegetic noise of passing cars seems hostile. It was an action that carried real personal risk. Poe spoke about “circumnavigating expectations” with his work, and indeed, “Let ‘im Move You: A Study and This is a Success” is a strange, eclectic mixture that has roots in many cultural traditions, but no true home. The work changes with the context of each space it’s performed in and with each audience it’s performed for. Poe challenges viewers by confronting them simultaneously with pleasure and with a self-awareness of their gazes meeting his black, queer body.

Robinson got up, and Poe kneeled in front of him. Hands out stiff in a near embrace, they shared breaths as Robinson slowly sank into Poe’s lap. They rocked each other back and forth, sharing breaths, touching lips, but not kissing. “Do you want not to know me?” Robinson asked into Poe’s slightly open mouth. “I want not to know you,” replied Poe into Robinson’s. A few more mumbled exchanges. “Let us dissolve into one another.”

Beacham appeared and stood behind them. Still locked in an embrace, they arched their backs away from each other, and Beacham pulled a chartreuse henley over Poe’s head. He placed a dark green jersey over Robinson’s head. Still clutching each other, they moved into the audience. Beacham pulled off their track shorts and dressed them in pants leg by leg. Flinging themselves back against the wall, hands stretched out, the dancers reached for each other. The DJ, Zen Jefferson, stepped away from his booth and, sharpie in hand, traced their profiles gesturing in eternal longing. They moved, and the line followed them. Robinson walked away and melted into the audience. This marked the end of the first piece.

Jumatatu Poe, William Robinson, and Jermone Donte Beacham in Jumatatu Poe’s “Let ‘im Move You: A Study” (2013/16) and “Let ‘im Move You: This is a Success” (2016) at ICA Philadelphia

A throbbing beat picked up, a remix of Erykah Badu’s “Trill Friends.” The ICA transformed from a rarified art gallery into a club. Now Poe and Beacham danced together, smiling and twirling. Step to the left, hands up, folded on top of the head, point out, turn, hands up again, hands on hips, twirl. Poe took out his smartphone and posed, Beacham just behind him. They grinned for the screen — he was taking live video. Jubilant, he pranced around the room, weaving his roving video selfie through the crowd, which shifted to accommodate his whims. We watched him watching himself. He exited the gallery, and everyone craned their necks, wondering, should we follow? All rules had been broken. Anything was possible here. He returned momentarily, put the phone away, and swept into a pose with Beacham on the stage. They turned away from each other and faced the crowd.

Poe locked eyes with me and approached, a toothy smile painted on his face. I held his gaze, wondering when it would break, wondering if I was about to become part of the performance — but of course, I already was. It was utterly infectious, and I couldn’t help but grin back. He looked out across the room and picked four members of his ensemble who’d been embedded in the audience. They joined him on the stage and writhed together to Ciara’s “I’m Out,” then snaked through the audience. The floor vibrated with beats and electricity.

Jumatatu Poe’s “Let ‘im Move You: This is a Success” (2016) at ICA Philadelphia

The group danced out of the gallery to a remix of Beyoncé’s “Sorry,” heading onto the landing, lassoing with their arms as they moved down the ICA stairs and into the lobby. The performance was boundless, breaking the fourth wall, transgressing the space of the stage, then the gallery, and ultimately the viewer’s voyeuristic pleasure. This time, the audience followed, enraptured and watching from the balcony. Arms raised in a final movement, the dancers finished, as waves upon waves of raucous applause were showered upon them.

Jumatatu Poe’s “Let ‘im Move You: This is a Success” (2016) at ICA Philadelphia

Jumatatu Poe’s “Let ‘im Move You: A Study” and “Let ‘im Move You: This is a Success” were performed at the Institute of Contemporary Art (University of Philadelphia, 118 S 36th Street) on January 22. Endless Shout continues through March 19.

The post Plié Meets Twerk in a Performance of Black Queer Joy appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2k5Ce4B

via IFTTT

0 notes