#she says medic in german has an interesting mix of professionalism and respect mixed with some rude language

Photo

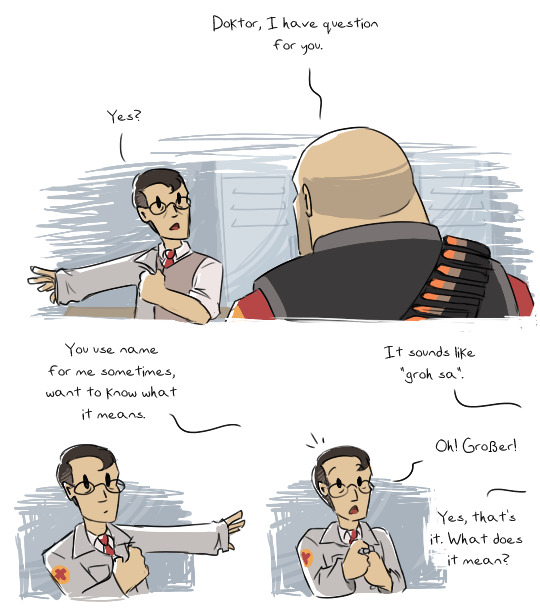

I was talking with my friend yamina about German endearments for these two and she suggested Großer (big boy (fond)) which was too cute, I had to do something with it.

[patreon]

#team fortress 2#heavy#medic#heavymedic#red oktoberfest#z art#z comic#very beautiful very powerful#i love my gigantic husband#i was wondering if there was something that fit better than schatzi or liebling and this is perfect#she says medic in german has an interesting mix of professionalism and respect mixed with some rude language#he uses the formal you! and apparently sounds like how someone his age would sound like at this time period#i just love stuff like this don't mind me#(she thinks his fake german in english is hilarious)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Magic Week: Witchcraft in Early Medieval Europe

Apologies for not getting to this last week, but I will try to be at least semi-reliable about posting these. If you missed it: I’m teaching a class on magic and the supernatural in the Middle Ages this semester, and since the Tumblr people also wanted to be learned, I am here attempting to learn them by giving a sort of virtual seminar.

Last week was the introduction, where we covered overall concepts like the difference between magic, religion, and science (is there one?), who did magic benefit (depends on who you ask), was magic a good or a bad thing in the medieval world (once again, It’s All Relative) and who was practicing it. We also brought in ideas like the gendering of supernatural power (is magic a feminine or a masculine practice, and does this play into larger gendered concepts in society?) and did some basic myth-busting about the medieval era. No, not everybody was super religious and mind-controlled by the church. No, they were not all poor farmers. No, not every woman was Silent, Raped, and Repressed. Magic was a common and folkloric practice on some level, but it was also the concern of educated and literate ‘worldly’ observers. We can’t write magic off as the medieval era simply ‘not knowing any better,’ or having no more sophisticated epistemology than rudimentary superstition. These people navigated thousands of miles without any kind of modern technology, built amazing cathedrals requiring hugely complex mathematical and engineering skill, wrote and translated books, treatises, and texts, and engaged with many different fields of knowledge and areas of interest. They subjected their miracle stories to critical vetting and were concerned with proving the evidentiary truth of their claims. We cannot dismiss magic as them having no alternative explanation or way of thinking about the world, or being sheltered naïve rustics.

This week, we looked at some primary sources discussing ‘witchcraft’ beliefs in early medieval Europe, which for our purposes is about 500—eh we’ll say 1000 C.E. We also thought about some questions to pose to these texts. Where did belief in witchcraft – best known for early modern witch hunts – come from? How did it survive through centuries of cultural Christianisation? Why was it viewed as useful or as threatening? Scholars have tended to argue for a generic mystical ‘shamanism’ in pre-Christian Europe, which isn’t very helpful (basically, it means ‘we don’t have enough evidence, so fuck if we know!’). They have also assumed that these were ‘superstitions’ or ‘relics’ of pagan belief in an otherwise Christian culture, which is likewise not helpful. We don’t have time to get into the whole debate, but yes, you can imagine the kind of narratives and assumptions that Western historiography has produced around this.

At this point, Europe was slowly, but by no means monolithically, becoming Christian, which meant a vast remaking of traditional culture. There was never a point where beliefs and practices stopped point-blank being pagan and became Christian instead; they were always hybrid, and they were always subject to discussion and debate. Obviously, people don’t stop doing things they have done a particular way for centuries overnight. (Once again, this is where we remind people that the medieval church was not the Borg and had absolutely no power to automatically assimilate anyone.) Our first text, the ‘Corrector sive medicus,’ which is the nineteenth chapter of Burchard of Worms’ Decretum, demonstrates this. The Decretum is a collection of ecclesiastical law, dating from early eleventh-century Germany. This is well after Germany was officially ‘Christianised,’ and after the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire as an explicitly Christian polity (usually dated from Charlemagne’s coronation on 25 December 800; this was the major organising political unit for medieval Germany and the Carolingians were intensely obsessed with divine approval). And yet! Burchard is still extremely concerned with the prevalence of ‘magical’ or ‘pagan’ beliefs in his diocese, which means people were still doing them.

The Corrector is a handbook setting out the proper length of penances to do (by fasting on bread and water) for a variety of transgressions. It can seem ridiculously nitpicky and overbearing in its determination to prescribe lengthy penances for magical offenses, which are mixed in among punishments for real crimes: robbery, theft, arson, adultery, etc. This might seem to lend legitimacy to the ‘killjoy medieval church oppressing the people’ narrative, except the punishments for sexual sins are actually much lighter than in earlier Celtic law codes. If you ‘shame a woman’ with your thoughts, it’s five days of penance if you’re married, two if you aren’t, but if you consult an oracle or take part in element worship or use charms or incantations, it could be up to two years.

Overall, the Corrector gives us the impression that eleventh-century German society was a lot more worried about whether you were secretly cursing your neighbour with pagan sorcery, rather than who you’re bonking, even though sexual morality is obviously still a concern, and this reflected the effort of trying to explicitly and completely Christianise a society that remained deeply attached to its traditional beliefs and practices. (There’s also a section about women going out at night and running naked with ‘Diana, Goddess of the Pagans’, which sounds awesome sign me up.) Thus there is here, as there will certainly be later, a gendered element to magic. Women could be witches, enchantresses, sorceresses, or other possible threats, and have to be closely watched. Nonetheless, there’s no organised societal persecution of them. Formal witch hunts and witch trials are decidedly a post-Renaissance phenomenon (cue rant about how terrible the Renaissance was for women). So as much as we stereotype the medieval world as supposedly being intolerant and repressive of women, witch hunts weren’t yet a thing, and many educated women, such as Trota of Salerno, had professional careers in medicine.

The solution to this problem of magical misuse is not to stop or destroy magic, since everyone believes in it, but to change who is legitimately allowed to access it. Valerie Flint’s article, ‘The Early Medieval Medicus, the Saint – and the Enchanter’ discusses the renegotiation of this ability. Essentially, there were three categories of ‘healer’ figure in the early Middle Ages: 1) the saint, whose miraculous power was explicitly Christian; 2) the ‘medicus’ or doctor, who used herbal or medical treatment, and 3) the ‘enchanter’, who used pagan magical power. According to the ecclesiastical authors, the saint is obviously the best option, and believing in/appealing to this figure will give you cures beyond the medicus’ ability, as a reward for your faith. The medicus tries his best and has good intentions, but is limited in his effectiveness and serves in some way as the saint’s ‘fall guy’. Or: Anything the Doctor Can (Or Can’t) Do, The Saint Can Do Better. But the doctor has enough social authority and respected knowledge to make it a significant victory when the saint’s power supersedes him.

On the other hand, the ‘enchanter’ is basically all bad. He (or often, she) makes the same claim to supernatural power as the saint, but the power is misused at best and actively malicious and uncontrollably destructive at worst. You are likely to be far worse off after having consulted the enchanter than if you did nothing at all. Both the saint and the enchanter are purveyors of ‘magical’ power, but only the saint has any legitimate claim (again, according to our church authors, whose views are different from those of the people) to using it. The saint’s power comes from God and Jesus Christ, the privileged or ‘true’ source of supernatural ability, while the enchanter is drawing on destructive and incorrect pagan beliefs and making the situation worse. The medicus is a benign and well-intentioned, if not always effective, option for healing, but the enchanter is No Good Very Bad Terrible.

The fact that ecclesiastical authors have to go so hard against magic, however, is proof of the long-running popularity of its practitioners. The general public is apparently still too prone to consult an enchanter rather than turn to the church to solve their problems. The church doesn’t want to eradicate these practices entirely, but insists that people call upon God/Christ as the authority in doing them, rather than whatever local or folkloric belief has been the case until now. It’s not destroying magic, but repurposing and redefining it. What has previously been the unholy domain of the pagan is now proof of the ultimate authority of Christianity. If you’re doing it right, it’s no longer pagan sorcery, but religious miracles or devotion.

Overall: what role does witchcraft play in early medieval Europe? The answer, of course, is ‘it’s complicated.’ We’re talking about a dynamic, large-scale transformation and hybridising of culture and society, as Christian religion and society became more prevalent over long-rooted pagan or traditional beliefs. However, these beliefs arguably never fully vanished, and were remade, renamed, and allowed to stay, without any apparent sense of contradiction on the part of the people practicing them. Ecclesiastical authorities were extremely concerned to identify and remove these ‘pagan’ elements, of course, but the general public’s relationship with them was always more nuanced. When dealing with medieval texts about magic, we have a tendency to prioritise those that deal with a definably historical person, event, or place, whereas clearly mythological stories referring to supernatural creatures or encounters are viewed as ‘less important’ or as the realm of historical fiction or legend. This is a mistake, since these texts are still encoding and transmitting important cultural referents, depictions of the role of magic in society, and the way in which medieval people saw it as a helpful or hurtful force. We have to work with the sources we have, of course, but we also have to be especially aware of our critical assumptions and prejudices in doing so.

It should be noted that medieval authors were very concerned with proving the veracity of their miracle narratives; they did not expect their audiences to believe them just because they said so. This is displayed for example in the work of two famous early medieval historians, Gregory of Tours (c.538—594) and the Venerable Bede (672/3—735). Both Gregory’s History of the Franks and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People contain a high proportion of miracle stories, and both of them are at pains to explain to the reader why they have found these narratives reliable: they knew the individual in question personally, or they heard the story from a sober man of good character, or several trusted witnesses attested to it, or so forth. Trying to recover the actual historicity of reported ‘miracle’ healings is close to impossible, and we should resist the cynical modern impulse to say that none of them happened and Gregory and Bede are just exaggerating for religious effect. We’re talking about some kind of experienced or believed-in phenomena, of whatever type, and obviously in a pre-modern society, your options for healthcare are fairly limited. It might be worth appealing to your local saint to do you a solid. So to just dismiss this experience from our modern perspective, with who knows how much evidence lost, in an entirely different cultural context, is not helpful either. There’s a lot of sneering ‘look at these unenlightened religious zealots’ under-and-overtones in popular conceptions of the medieval era, and smugly feeling ourselves intellectually superior to them isn’t going to get us very far.

Next week: Ideas about the afterlife, heaven, hell, the development of purgatory, the kind of creatures that lived in these realms, and their representation in art, culture, and literature.

Further Reading:

Alver, B.G., and T. Selberg, ‘Folk Medicine As Part of a Larger Complex Concept,’ Arv, 43 (1987), 21–44.

Barry, J., and O. Davies, eds., Witchcraft Historiography (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007)

Collins, D., ‘Magic in the Middle Ages: History and Historiography’, History Compass, 9 (2011), 410–22.

Flint, V.I.J, ‘A Magical Universe,’ in A Social History of England, 1200-1500, ed. by R. Horrox and W. Mark Ormrod (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 340–55.

Hall, A., ‘The Contemporary Evidence for Early Medieval Witchcraft Beliefs’, RMN Newsletter, 3 (2011), 6-11.

Jolly, K.L., Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf Charms in Context (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996)

Kieckhefer, R., Magic in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000)

Maxwell-Stuart, P.G., The Occult in Mediaeval Europe (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2005)

Storms, G., Anglo-Saxon Magic (The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1947)

Tangherlini, T., ‘From Trolls to Turks: Continuity and Change in Danish Legend Tradition’, Scandinavian Studies, 67 (1995), 32–62.

45 notes

·

View notes