#so i went to get some more from wikimedia commons of course

Photo

Migraine auras from wikimedia commons

#saw the first one posted by powerburial and was overwhelmed by how beautiful it was#so i went to get some more from wikimedia commons of course#i had two others but tumblr wouldnt let me upload them for some reason.#the auras i get are most like the second and third images#my uploads#wikimedia commons#favourite#gif

2K notes

·

View notes

Link

Silvio Gesell hated money. A German entrepreneur who moved to Argentina for business in the late 19th century, he witnessed a massive financial crash in 1890 that convinced him that money was behind the world's economic problems: poverty, inequality, unemployment, stagnation.

The problem, Gesell believed, was that money served two roles that often came into conflict: It was a way for people to store wealth, and it was the thing everybody needed to conduct business. The fact that money could store wealth meant its holders had a reason to cling to it, especially in crises like the one he saw in Argentina, when opportunities to safely put that money elsewhere looked grim. It was a typical story. When people got scared, they hoarded cash and brought business to a standstill. It led, Gesell said, to a situation of "poverty amid plenty."

Gesell wanted to create a new kind of money — a money that would "rot like potatoes" and "rust like iron" so no one would want to hoard it, a money that was "an instrument of exchange and nothing else." And the crazy part is that he did create it. Through a series of pamphlets, articles and books, Gesell inspired a worldwide movement that introduced a completely new form of money. It's one of the most fascinating, and largely forgotten, stories in economic history.

But after 70 years of obscurity, Gesell is making a comeback. All of a sudden, this obscure radical from another age has his name and ideas popping up in unlikely places — like speeches of leaders at the U.S. Federal Reserve, research papers of the International Monetary Fund and the pages of the Financial Times. As the industrialized world grapples with stagnation and as markets signal another recession, policymakers are struggling to figure out what to do. Could Gesell provide an answer?

Money with an expiration date

Gesell was born in 1862 to a German father and a French mother, and he was raised in what is now Belgium. Back then, it was part of the expanding Prussian empire. At 24, he moved to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he worked as an importer and manufacturer and did well for himself. On the side, he taught himself economics.

In 1891, hoping to end the depression in Argentina, Gesell published his first work, "Currency Reform as a Bridge to the Social State." He proposed a new kind of paper money that would have an expiration date. To avoid expiration, the bills would have to be periodically stamped for a fee. With no new stamp, they would become worthless. In this system, saving money would cost you money. Savings, in other words, would have a negative interest rate. Only by spending or investing it would you be able to avoid stamp fees.

Gesell called it "free money" (or Freigold) — "free" because he believed it would be freed from hoarding and also because it would encourage bankers to lend money without charging interest. The logic was this: If you're holding on to something that's dropping in value, you'll happily part with it — even if it means that it won't make you more money than you started with. It's like a game of hot potatoes. You want to pass it on. Gesell believed this would keep money whizzing through the system, preventing future depressions and increasing public prosperity.

It was a completely radical idea, especially during a time when nations were on the gold standard. That system latched money to the stable value of gold, which meant currency was a pretty safe place to store wealth. Gesell was saying he didn't want money to be like gold. He wanted it to be like most other objects, which decay and rust and go bad. Of course, many people hated this idea, especially people with a lot of money.

In 1899, Gesell began moving back and forth between Europe and Argentina, spreading the gospel of free money and writing extensively on other matters as well. He had a bunch of eccentric views, criticizing monogamous relationships and advocating free love. He lived in a vegetarian commune near Berlin for a time. He was a bohemian utopian who advocated for peace between nations. He was critical of big business and finance, but he believed in individual freedom and market competition. And he was a committed anti-racist. As fascism rose in Germany, Gesell would call the scapegoating of Jews for the nation's problems "a colossal injustice."

Wikimedia Commons

After World War I, Gesell watched Europe descend into political and economic chaos. In 1919, anarchist revolutionaries in Munich, Germany, took the helm of the short-lived Bavarian Republic, and they persuaded Gesell to become their finance minister. Led by pacifist poets and playwrights, it has been called "one of the strangest governments in the history of any country." Gesell began pursuing a program that included land reform, a basic income for women with children and, of course, stamped money. But the job lasted less than a week — ending after another group of revolutionaries, this time led by hard-line communists, overthrew the anarchist poets and playwrights. A year later, after the German government reasserted control, Gesell was tried for treason. But, successfully arguing that his only role and purpose was to rescue the Bavarian economy, he was acquitted after a one-day trial and went back to writing.

Free money becomes real money

For decades, money that expired unless stamped was mostly a theory. It took the Great Depression to make it a reality. As the economy went into a free-fall, people scrambled to find solutions. And in towns scattered throughout Europe and the United States, they found their solution in Gesell. The money reformer, who died in 1930 of pneumonia, would not live to see it.

In 1932, in the small town of Wörgl, Austria, a town leader, Michael Unterguggenberger, got Wörgl to issue stamped money as a way to combat skyrocketing unemployment and business closures. The town used it to pay the unemployed to do public works, and by all contemporary accounts, the system worked to lift the town out of misery.

The press dubbed it the "miracle of Wörgl," and it was one in a series of local experiments with stamped money. These experiments inspired many other struggling cities, like Hawarden, Iowa, and Anaheim, Calif., to do the same. It was around then that Gesell's work was finally published in English. With classical economics discredited by the prolonged depression and with leading economists scrambling to figure out what to do, many were inspired by Gesell. Among them were Irving Fisher and John Maynard Keynes, two of the most influential economists of the 20th century.

In 1933, Fisher wrote a short book inspired by Gesell's ideas called Stamp Scrip. Fisher was an economist at Yale University, and he's now somewhat unfairly remembered for making overly optimistic predictions before the crash of 1929. He lobbied Congress to institute stamped money to provide relief to a distressed America. U.S. senators introduced a bill (S. 5125) that would have issued a billion dollars of stamped money to be distributed nationally. But it did not end up becoming law. Perhaps that's because that year was already seeing huge changes, with newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt implementing the New Deal and taking the U.S. off the gold standard.

Keynes, in 1936, dedicated five pages to Gesell in a concluding chapter of his magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. While critiquing some of Gesell's overall theory, Keynes concluded, "The idea behind stamped money is sound."

Why do we care about this now?

After World War II, the industrialized world entered a remarkable period of economic growth. And central banks, now off a rigid gold standard, played a greater role in managing money to ease the ups and downs of the market. Negative-interest money lost its allure, and Gesell was mostly forgotten.

But the world's central banks are now thinking about how to keep money moving again. When the economy enters a downturn, they usually cut interest rates to encourage spending. But interest rates are already close to zero, which could be a huge problem in another recession. For a long time, economists believed rates couldn't go negative for a simple reason: If saving in places like a bank costs people money, they will instead just hoard cash, which won't cost them money. Cash becomes a roadblock to economic stimulus. One way around this is higher inflation, which devalues or "taxes" money in real terms, but central banks like the Fed have been showing that they have much less power to increase inflation than previously thought.

Central banks in Europe and Japan have been experimenting with teeny-tiny negative interest rates as a way to stimulate the economy, but the issue still remains that people will start hoarding cash if rates go significantly negative. It's why serious economic thinkers consider Gesell relevant again.

In our technological age, a Gesellian system of unhoardable cash wouldn't actually have to involve stamping paper bills for a fee. It could involve high-tech physical cash, such as magnetic strips that allow the government to impose a "Gesell tax" on holding cash, as one economist proposed some years ago. Harvard University's Kenneth Rogoff has been advocating we get rid of paper money altogether and move almost completely to a system of electronic cash. He believes it could give central banks the power to impose negative interest rates deep enough to rescue our economy from future recessions. In all of this, Gesell was a pioneer.

Silvio Gesell has been called everything from a "libertarian socialist" to an "anarchist" to a "free spirit" to a "crank." John Maynard Keynes had a much more affectionate term for him: a "strange, unduly neglected prophet."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Murderess from the Grunewald (30): Skeletons in the closet (1)

(JVA Berlin-Moabit - Entrance * Source: G.Elser [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. James Fraser was well prepared when he got out of his car and walked towards the entrance to the Berlin-Moabit Prison.

The lawyer in him was well prepared. The evening before he had recapitulated the conversation with Professor Nerz once again and then put down his thoughts in writing. After a break during which he had dinner and a shower, he had supplemented the resulting script with his notes from the morning. Finally, he had entered a revised version into his laptop. He carried a copy of this version in his briefcase. Everything was logically thought through, clearly structured and arranged. If he could put forward his arguments correctly, Claire would surely understand why they had to talk about her past again. She was an insightful person, he was sure, she would understand.

The man in him felt less prepared. He was happy to finally see Claire again. Would she be well? Would she let him embrace her again? Or would she refuse him? Jamie didn’t know. How often had he seen people change their minds overnight? He was looking forward to seeing Claire. But maybe he should lower his expectations? It was conceivable that she too had changed her mind about him. Maybe she regretted that she had shown herself so vulnerable, so open?

Once again he breathed deeply in and out. He had to put those thoughts aside. Now he had to concentrate completely on her trial’s preparation. Once the trial had been won, he could see further.

Ten minutes later Jamie stood in front of the door to the consultation room. The prison officer unlocked the door and let him in. Claire stood at the table and turned to him as he entered. Wearing a dark red sweater and black jeans, she approached him and on her face, he spotted a slight smile.

(”Fenster” by StockSnap)

"Good morning, Jamie."

He put his briefcase on the table and spread his arms slightly.

"Good morning, Claire."

To his surprise, she glided into his arms without hesitation. When she put her head on his shoulder, he closed his eyes for a moment. Pictures rose before his inner eyes of which he could never tell anyone anything. And when he had to let her go again, a slight sting ran through him.

"You look ... good, Claire. Are you feeling a little better?

"Yes, thank you. A little. I'm glad you're here, Jamie."

They sat down and Jamie opened his briefcase to take a stack of papers out of it.

"I have some good news. There's some progress, Claire."

"That's good to hear."

"I talked to David de Koning. As I hoped, he will support us if we provide him with exclusive information and give him the desired exclusive interview. It's about one interview, Claire, one single interview. Not more."

Jamie handed her a stapled stack of papers.

"Here's a draft of the contract I or we could sign with him. Please read it through and tell me what you think about it the next time I visit you."

"When will that be?" Claire asked as she took the papers.

"Probably in two days. If you have any questions or remarks, you can write them down on the draft.”

She nodded, then put the pile of paper aside.

“Papier” by Free-Photos

"I brought us something to drink again."

Jamie reached into the briefcase again and took out two 0.5 liter bottles, one coke, one water. He had bought the double amount because he assumed that the conversation would last longer this time. He had also bought some nut and chocolate bars with him. But he left all of that in his briefcase at that moment.

"Coke again?”

"Yes, gladly. If I may?”

"Sure."

He handed her the coke and opened the water bottle for himself. Claire took a sip and then put it down smiling.

"Actually, I'm not such a big fan of coke ... it's interesting what you get cravings for when you can't buy everything anymore," she said thoughtfully.

Jamie waited a moment. He tried to concentrate and gather his strength. Then he said as calmly as possible:

"Yesterday I had a detailed conversation with Professor Nerz. I told you that I wanted to get advice on our dealings with the press and the media as a whole.".

Claire nodded again.

"The conflict with the press, with the media, could become very hard. But, Claire," Jamie paused for a moment, then stretched both arms across the table and grabbed her hands, "You're a brave, a strong woman. You will not only survive this, but you will also master it. I am convinced of that. And we," he pulled his hands back and reached for another pile of paper, "will support you with all the legal means at our disposal."

Now Claire reached for his right hand.

"Thank you. For everything.”

Jamie nodded, then he looked at his script and went on:

"I share Professor Nerz's opinion that we need to split your defense. You and I and the lawyers of our law firm, we focus entirely on the trial here in court. Professor Nerz's firm will focus entirely on what is called litigation PR."

"Litigation PR?"

Claire looked at him questioningly.

"That's what we call public relations in a lawsuit to avoid damage to a client's reputation."

"Damage to ... reputation?" Claire asked, and her face darkened.

“Claire," again Jamie gathered strength and tried not to let nervousness arise in his voice, "we have to face the fact that the media, especially the newspapers, will take up the case. This market is very competitive and it may be that the media will inflate the case ... just to get more readers."

"What ... what does that ... mean, specifically?"

Jamie didn't miss the uncertainty in Claire's voice.

"It could be that they will spread things about you that do not correspond to the truth. It could also be that they're spreading suspicions, speculations, all just to increase the circulation of their papers or the number of clicks on their websites."

Claire's eyes had widened more and more as she listened to Jamie. He hated that he could literally watch how what he had said created fear in her soul. As calmly as possible he continued:

"But I assure you that Professor Nerz's team will do everything to defend you in this field. This means that they will sue anyone who spreads something about you that is not true or damages your reputation. But not only that. If the media pays more attention to your case, Professor Nerz's team will do everything they can to spread our view of your story in public. They will do that very actively."

He paused for a moment to see if Claire had understood his remarks. She breathed audibly out and in. Then she nodded and - after a quick look at his script - Jamie continued.

"Professor Nerz suggested two colleagues from his firm, both highly qualified media lawyers. It depends on who is free when the trial begins. He or she will then take over the task."

Claire was still holding his hand and he felt her grip tighten around her. To reassure her (that he was what he was trying to tell himself), he put his hand over hers and looked at her.

“Hände halten” by StockSnap

"Claire," he then said, "there's something else we need to talk about."

She nodded and her gaze reflected a mixture of expectation and unconfirmed fear.

"We've talked about this before ... and it's not that I don't believe you, but ... because of the possibility that the media might dig into your life, I have to ask you again if there is anything ... things that have happened between you and your husband ... that the press could dig up and exploit ... things that could harm you?"

She looked at him and her still expectant look darkened instantly.

"Claire, I believe you and I'm very sorry that I have to ask you about these things ... but were there any ... fights between you and your husband that might even have become physical conflicts and that others might know about?”

She leaned her head on both hands and closed her eyes. Then Jamie heard her crying softly. But just moments later she seemed to gather herself together. Before he could do anything, she reached into the pocket of her trousers and pulled out a handkerchief to wipe off her tears and blow her nose. Quietly she said:

"There were some such ... incidents, if you will call it that."

"Take your time, Claire, we have no hurry..."

"It won't get any better, Jamie, if I..."

Again she began to sob and again tears ran down her face. Jamie handed her one of his handkerchiefs. She took it with a grateful look.

“Platzregen” by Photones [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

"Once ...," she said quietly, "... it was at the very beginning of our time in Berlin ... Frank came home late ... outside it was already dark. I still remember well because ... a thunderstorm raged ... it was one of those ... you know one of these immense storms that we have been experiencing again and again in Berlin for some years now ... I still remember well, because I had not expected such storms in Europe at all."

Jamie nodded.

"Fortunately, our house was not in an area affected by flooding, but the storm that evening was particularly frustrating. The electricity came and went ... the lamps flickered all the time ... and at some point, I switched off all the lights and lit a number of candles. When Frank came home, I sat in the living room and read. He greeted me, then he pulled himself a whiskey and sat down in a chair next to me. He began to tell me a rather confusing story. He said he saw a man standing at the gate to our property, looking up to our living room, to me. You must know, you could see into some rooms of the house from down there, i.e. you could see when the room was lit and someone was in the room. At least when the person was standing near the windows. Then Frank started asking me questions, strange questions. In the course of the conversation, he became more and more insistent. It wasn't really a conversation between two equal partners, it was more of an interrogation. Suddenly I realized that he was accusing me of having an affair with this man."

Again Claire supported her head in both hands. Then she shook her head.

"The whole thing was just highly surreal. He suggested that this man might have been a patient of mine from the hospital. That I had met him there and started an affair with him. I told him it wasn't true..."

She broke off and turned to the side. When she turned back to Jamie a few moments later, he saw more tears running down her face.

"He ... he then imperatively wanted to sleep with me. It ... it was as if he wanted to mark his property, ... that had nothing to do with love. Absolutely nothing. It was ... repulsive, animalistic. It was not the intimate togetherness of two lovers, it was ... it was ..."

Tears ran down her face, while she was searching for the right words.

"A rape in marriage?"

Jamie's asked the question carefully and as quietly as possible.

Claire looked at him with her red eyes, then she nodded.

"Yes, that it was. I ... I'm still ashamed of it today, but ... I didn't have the strength, I didn't have the strength to fight it back then."

Jamie reached for the coke bottle and pushed it over her. He nodded encouragingly. She grabbed the bottle and drank.

"Does anyone know about this ... incident?"

"Not that I know. I didn't tell anyone, I was too ashamed. I don’t know if Frank told anyone ..."

Claire raised and lowered her shoulders.

"It was the first time I had the impression that he got aroused by hurting me verbally or physically. When he could exercise his 'control' over me."

Jamie noted the word "thunderstorm" on the script in front of him. He had to gather all his strength to concentrate. He paused for a moment and thought, how good it was, that Frank Randall was already dead.

"What else happened?"

(”Bournemouth” by diego_torres)

Claire paused for a moment. Should she tell Jamie about what happened that night in Bournemouth? Should she tell him about the night when Frank tried to humiliate her again? No, she wouldn't be able to do that. Not now. This event was still following her like a dark shadow. If she would start and tell him now ... no, it was just too much. And who would know about it? Maybe the hotel staff had thought about it one way or another. But how many men were there who liked to 'drink one over their thirst' and whose wives then simply slept in another room? No, even if the press found out that they had been on holiday there and had slept in different rooms from a certain point in time on ... she could give a natural explanation for that.

She looked at Jamie.

"Excuse me, what did you say?”

"I asked if there were any more ... if there were any similar incidents?"

Claire stared for a moment at the black and white formica tabletop. Jamie was right. You should be better prepared for everything.

As for the Bournemouth story, she was sure there were no witnesses. And Frank certainly hadn't told any of his friends about it either. That would have been much too embarrassing.

And the only evidence for this incident was no longer available. She had taken the torn nightgown the next morning and packed it into her suitcase. For a long time, she had kept it as evidence in a hollow place in her wardrobe.

Just like the pictures she had taken of the bruises and hematomas that Frank's drunken 'tenderness' had left on her thighs.

Only after his death did she destroy all of this. She had deleted the pictures from the cloud and from her laptop and on one of the following days, she had burned the unusable nightgown in the fireplace. She had then put the ashes under the organic waste. Some days earlier, the gardener, who came regularly to mow the lawn and who took care of the garden, had filled the bin with grass and cut shrubs. The little bit of ash hadn't been noticed underneath. Some days later the bin had been picked up by the regular garbage collector.

“Aschenbecher aus Kristall” / “Cutted Ashtray” by Pavel Ševela [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

Although the police had suspected her immediately after Frank's death, nothing could be proved against her at that time. And the police investigations in the house had concentrated primarily on the stairs and the corridor.

The laptop containing the pictures was stored up in her desk at the Charité. And even if one had found these pictures ... she had put them in a folder containing numerous photos documenting the injuries of her patients ...

Their two bedrooms had also not been examined further and the explanation she gave to the officials for sleeping separately ("My husband snores strongly and I often come from the night shift in the hospital when he is already asleep") satisfied them at that time as well.

Claire didn't think that these things would be ever come up again. But then there was the incident with the heavy, glass ashtray ..."

Thank you very much for your interest. Next time read: "The Murderer from the Grunewald (31): Skeletons in the closet (2)"

#Outlander#Outlander Fan Fiction#TheMurderessfromtheGrunewald#Claire Beauchamp#Claire Randall#Claire Fraser#Frank Randall#Jamie Fraser#Adso the cat#Bismarck the dachshund#Berlin#Grunewald#Germany#Modern AU#Crime AU#jamie x claire#claire x jamie

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The end of the world: a history of how a silent cosmos led humans to fear the worst

by Thomas Moynihan

NASA

It is 1950 and a group of scientists are walking to lunch against the majestic backdrop of the Rocky Mountains. They are about to have a conversation that will become scientific legend. The scientists are at the Los Alamos Ranch School, the site for the Manhattan Project, where each of the group has lately played their part in ushering in the atomic age.

They are laughing about a recent cartoon in the New Yorker offering an unlikely explanation for a slew of missing public trash cans across New York City. The cartoon had depicted “little green men” (complete with antenna and guileless smiles) having stolen the bins, assiduously unloading them from their flying saucer.

By the time the party of nuclear scientists sits down to lunch, within the mess hall of a grand log cabin, one of their number turns the conversation to matters more serious. “Where, then, is everybody?”, he asks. They all know that he is talking – sincerely – about extraterrestrials.

The question, which was posed by Enrico Fermi and is now known as Fermi’s Paradox, has chilling implications.

youtube

Bin-stealing UFOs notwithstanding, humanity still hasn’t found any evidence of intelligent activity among the stars. Not a single feat of “astro-engineering”, no visible superstructures, not one space-faring empire, not even a radio transmission. It has been argued that the eerie silence from the sky above may well tell us something ominous about the future course of our own civilisation.

Such fears are ramping up. Last year, the astrophysicist Adam Frank implored an audience at Google that we see climate change – and the newly baptised geological age of the Anthropocene – against this cosmological backdrop. The Anthropocene refers to the effects of humanity’s energy-intensive activities upon Earth. Could it be that we do not see evidence of space-faring galactic civilisations because, due to resource exhaustion and subsequent climate collapse, none of them ever get that far? If so, why should we be any different?

A few months after Frank’s talk, in October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s update on global warming caused a stir. It predicted a sombre future if we do not decarbonise. And in May, amid Extinction Rebellion’s protests, a new climate report upped the ante, warning: “Human life on earth may be on the way to extinction.”

Meanwhile, NASA has been publishing press releases about an asteroid set to hit New York within a month. This is, of course, a dress rehearsal: part of a “stress test” designed to simulate responses to such a catastrophe. NASA is obviously fairly worried by the prospect of such a disaster event – such simulations are costly.

Space tech Elon Musk has also been relaying his fears about artificial intelligence to YouTube audiences of tens of millions. He and others worry that the ability for AI systems to rewrite and self-improve themselves may trigger a sudden runaway process, or “intelligence explosion”, that will leave us far behind – an artificial superintelligence need not even be intentionally malicious in order to accidentally wipe us out.

youtube

In 2015, Musk donated to Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute, headed up by transhumanist Nick Bostrom. Nestled within the university’s medieval spires, Bostrom’s institute scrutinises the long-term fate of humanity and the perils we face at a truly cosmic scale, examining the risks of things such as climate, asteroids and AI. It also looks into less well-publicised issues. Universe destroying physics experiments, gamma-ray bursts, planet-consuming nanotechnology and exploding supernovae have all come under its gaze.

So it would seem that humanity is becoming more and more concerned with portents of human extinction. As a global community, we are increasingly conversant with increasingly severe futures. Something is in the air.

But this tendency is not actually exclusive to the post-atomic age: our growing concern about extinction has a history. We have been becoming more and more worried for our future for quite some time now. My PhD research tells the story of how this began. No one has yet told this story, yet I feel it is an important one for our present moment.

I wanted to find out how current projects, such as the Future of Humanity Institute, emerge as offshoots and continuations of an ongoing project of “enlightenment” that we first set ourselves over two centuries ago. Recalling how we first came to care for our future helps reaffirm why we should continue to care today.

Extinction, 200 years ago

In 1816, something was also in the air. It was a 100-megaton sulfate aerosol layer. Girdling the planet, it was made up of material thrown into the stratosphere by the eruption of Mount Tambora, in Indonesia, the previous year. It was one of the biggest volcanic eruptions since civilisation emerged during the Holocene.

Mount Tambora’s crater. Wikimedia Commons/NASA

Almost blotting out the sun, Tambora’s fallout caused a global cascade of harvest collapse, mass famine, cholera outbreak and geopolitical instability. And it also provoked the first popular fictional depictions of human extinction. These came from a troupe of writers including Lord Byron, Mary Shelley and Percy Shelley.

The group had been holidaying together in Switzerland when titanic thunderstorms, caused by Tambora’s climate perturbations, trapped them inside their villa. Here they discussed humanity’s long-term prospects.

Read more: Why a volcano, Frankenstein, and the summer of 1816 are relevant to the Anthropocene

Clearly inspired by these conversations and by 1816’s hellish weather, Byron immediately set to work on a poem entitled “Darkness”. It imagines what would happen if our sun died:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air

Detailing the ensuing sterilisation of our biosphere, it caused a stir. And almost 150 years later, against the backdrop of escalating Cold War tensions, the Bulletin for Atomic Scientists again called upon Byron’s poem to illustrate the severity of nuclear winter.

Two years later, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (perhaps the first book on synthetic biology) refers to the potential for the lab-born monster to outbreed and exterminate Homo sapiens as a competing species. By 1826, Mary went on to publish The Last Man. This was the first full-length novel on human extinction, depicted here at the hands of pandemic pathogen.

Boris Karloff plays Frankenstein’s monster, 1935. Wikimedia Commons

Beyond these speculative fictions, other writers and thinkers had already discussed such threats. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in 1811, daydreamed in his private notebooks about our planet being “scorched by a close comet and still rolling on – cities men-less, channels riverless, five mile deep”. In 1798, Mary Shelley’s father, the political thinker William Godwin, queried whether our species would “continue forever”?

While just a few years earlier, Immanuel Kant had pessimistically proclaimed that global peace may be achieved “only in the vast graveyard of the human race”. He would, soon after, worry about a descendent offshoot of humanity becoming more intelligent and pushing us aside.

Earlier still, in 1754, philosopher David Hume had declared that “man, equally with every animal and vegetable, will partake” in extinction. Godwin noted that “some of the profoundest enquirers” had lately become concerned with “the extinction of our species”.

In 1816, against the backdrop of Tambora’s glowering skies, a newspaper article drew attention to this growing murmur. It listed numerous extinction threats. From global refrigeration to rising oceans to planetary conflagration, it spotlighted the new scientific concern for human extinction. The “probability of such a disaster is daily increasing”, the article glibly noted. Not without chagrin, it closed by stating: “Here, then, is a very rational end of the world!”

Tambora’s dust-cloud created ominous sunsets, such as this one painted by Turner, c. 1830–5. © Tate, CC BY-NC-ND

Before this, we thought the universe was busy

So if people first started worrying about human extinction in the 18th century, where was the notion beforehand? There is enough apocalypse in scripture to last until judgement day, surely. But extinction has nothing to do with apocalypse. The two ideas are utterly different, even contradictory.

For a start, apocalyptic prophecies are designed to reveal the ultimate moral meaning of things. It’s in the name: apocalypse means revelation. Extinction, by direct contrast, reveals precisely nothing and this is because it instead predicts the end of meaning and morality itself – if there are no humans, there is nothing humanly meaningful left.

And this is precisely why extinction matters. Judgement day allows us to feel comfortable knowing that, in the end, the universe is ultimately in tune with what we call “justice”. Nothing was ever truly at stake. On the other hand, extinction alerts us to the fact that everything we hold dear has always been in jeopardy. In other words, everything is at stake.

Extinction was not much discussed before 1700 due to a background assumption, widespread prior to the Enlightenment, that it is the nature of the cosmos to be as full as moral value and worth as is possible. This, in turn, led people to assume that all other planets are populated with “living and thinking beings” exactly like us.

Although it only became a truly widely accepted fact after Copernicus and Kepler in the 16th and 17th centuries, the idea of plural worlds certainly dates back to antiquity, with intellectuals from Epicurus to Nicholas of Cusa proposing them to be inhabited with lifeforms similar to our own. And, in a cosmos that is infinitely populated with humanoid beings, such beings – and their values – can never fully go extinct.

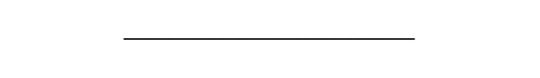

Star cluster Messier 13 in Hercules, 1877. Wikimedia Commons

In the 1660s, Galileo confidently declared that an entirely uninhabited or unpopulated world is “naturally impossible” on account of it being “morally unjustifiable”. Gottfried Leibniz later pronounced that there simply cannot be anything entirely “fallow, sterile, or dead in the universe”.

Along the same lines, the trailblazing scientist Edmond Halley (after whom the famous comet is named) reasoned in 1753 that the interior of our planet must likewise be “inhabited”. It would be “unjust” for any part of nature to be left “unoccupied” by moral beings, he argued.

Around the same time Halley provided the first theory on a “mass extinction event”. He speculated that comets had previously wiped out entire “worlds” of species. Nonetheless, he also maintained that, after each previous cataclysm “human civilisation had reliably re-emerged”. And it would do so again. Only this, he said could make such an event morally justifiable.

Later, in the 1760s, the philosopher Denis Diderot was attending a dinner party when he was asked whether humans would go extinct. He answered “yes”, but immediately qualified this by saying that after several millions of years the “biped animal who carries the name man” would inevitably re-evolve.

This is what the contemporary planetary scientist Charles Lineweaver identifies as the “Planet of the Apes Hypothesis”. This refers to the misguided presumption that “human-like intelligence” is a recurrent feature of cosmic evolution: that alien biospheres will reliably produce beings like us. This is what is behind the wrong-headed assumption that, should we be wiped out today, something like us will inevitably return tomorrow.

youtube

Back in Diderot’s time, this assumption was pretty much the only game in town. It was why one British astronomer wrote, in 1750, that the destruction of our planet would matter as little as “Birth-Days or Mortalities” do down on Earth.

This was typical thinking at the time. Within the prevailing worldview of eternally returning humanoids throughout an infinitely populated universe, there was simply no pressure or need to care for the future. Human extinction simply couldn’t matter. It was trivialised to the point of being unthinkable.

For the same reasons, the idea of the “future” was also missing. People simply didn’t care about it in the way we do now. Without the urgency of a future riddled with risk, there was no motivation to be interested in it, let alone attempt to predict and preempt it.

It was the dismantling of such dogmas, beginning in the 1700s and ramping up in the 1800s, that set the stage for the enunciation of Fermi’s Paradox in the 1900s and leads to our growing appreciation for our cosmic precariousness today.

But then we realised the skies are silent

In order to truly care about our mutable position down here, we first had to notice that the cosmic skies above us are crushingly silent. Slowly at first, though soon after gaining momentum, this realisation began to take hold around the same time that Diderot had his dinner party.

One of the first examples of a different mode of thinking I’ve found is from 1750, when the French polymath Claude-Nicholas Le Cat wrote a history of the earth. Like Halley, he posited the now familiar cycles of “ruin and renovation”. Unlike Halley, he was conspicuously unclear as to whether humans would return after the next cataclysm. A shocked reviewer picked up on this, demanding to know whether “Earth shall be re-peopled with new inhabitants”. In reply, the author facetiously asserted that our fossil remains would “gratify the curiosity of the new inhabitants of the new world, if there be any”. The cycle of eternally returning humanoids was unwinding.

In line with this, the French encyclopaedist Baron d’Holbach ridiculed the “conjecture that other planets, like our own, are inhabited by beings resembling ourselves”. He noted that precisely this dogma – and the related belief that the cosmos is inherently full of moral value – had long obstructed appreciation that the human species could permanently “disappear” from existence. By 1830, the German philosopher F W J Schelling declared it utterly naive to go on presuming “that humanoid beings are found everywhere and are the ultimate end”.

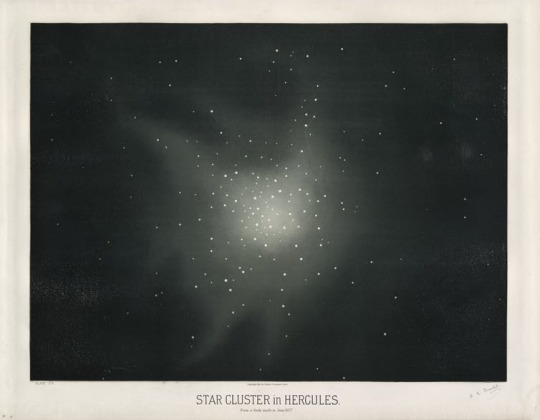

Figures illustrating articles on astronomy, from the 1728 Cyclopaedia. Wikimedia Commons

And so, where Galileo had once spurned the idea of a dead world, the German astronomer Wilhelm Olbers proposed in 1802 that the Mars-Jupiter asteroid belt in fact constitutes the ruins of a shattered planet. Troubled by this, Godwin noted that this would mean that the creator had allowed part of “his creation” to become irremediably “unoccupied”. But scientists were soon computing the precise explosive force needed to crack a planet – assigning cold numbers where moral intuitions once prevailed. Olbers calculated a precise timeframe within which to expect such an event befalling Earth. Poets began writing of “bursten worlds”.

The cosmic fragility of life was becoming undeniable. If Earth happened to drift away from the sun, one 1780s Parisian diarist imagined that interstellar coldness would “annihilate the human race, and the earth rambling in the void space, would exhibit a barren, depopulated aspect”. Soon after, the Italian pessimist Giacomo Leopardi envisioned the same scenario. He said that, shorn of the sun’s radiance, humanity would “all die in the dark, frozen like pieces of rock crystal”.

Galileo’s inorganic world was now a chilling possibility. Life, finally, had become cosmically delicate. Ironically, this appreciation came not from scouring the skies above but from probing the ground below. Early geologists, during the later 1700s, realised that Earth has its own history and that organic life has not always been part of it. Biology hasn’t even been a permanent fixture down here on Earth – why should it be one elsewhere? Coupled with growing scientific proof that many species had previously become extinct, this slowly transformed our view of the cosmological position of life as the 19th century dawned.

Copper engraving of a pterodactyl fossil discovered by the Italian scientist Cosimo Alessandro Collini in 1784. Wikimedia Commons

Seeing death in the stars

And so, where people like Diderot looked up into the cosmos in the 1750s and saw a teeming petri dish of humanoids, writers such as Thomas de Quincey were, by 1854, gazing upon the Orion nebula and reporting that they saw only a gigantic inorganic “skull” and its lightyear-long rictus grin.

The astronomer William Herschel had, already in 1814, realised that looking out into the galaxy one is looking into a “kind of chronometer”. Fermi would spell it out a century after de Quincey, but people were already intuiting the basic notion: looking out into dead space, we may just be looking into our own future.

Early drawings of Orion’s nebula by R.S. Newall, 1884. © Cambridge University, CC BY

People were becoming aware that the appearance of intelligent activity on Earth should not be taken for granted. They began to see that it is something distinct – something that stands out against the silent depths of space. Only through realising that what we consider valuable is not the cosmological baseline did we come to grasp that such values are not necessarily part of the natural world. Realising this was also realising that they are entirely our own responsibility. And this, in turn, summoned us to the modern projects of prediction, preemption and strategising. It is how we came to care about our future.

As soon as people first started discussing human extinction, possible preventative measures were suggested. Bostrom now refers to this as “macrostrategy”. However, as early as the 1720s, the French diplomat Benoît de Maillet was suggesting gigantic feats of geoengineering that could be leveraged to buffer against climate collapse. The notion of humanity as a geological force has been around ever since we started thinking about the long-term – it is only recently that scientists have accepted this and given it a name: “Anthropocene”.

youtube

Will technology save us?

It wasn’t long before authors began conjuring up highly technologically advanced futures aimed at protecting against existential threat. The eccentric Russian futurologist Vladimir Odoevskii, writing in the 1830s and 1840s, imagined humanity engineering the global climate and installing gigantic machines to “repulse” comets and other threats, for example. Yet Odoevskii was also keenly aware that with self-responsibility comes risk: the risk of abortive failure. Accordingly, he was also the very first author to propose the possibility that humanity might destroy itself with its own technology.

Acknowledgement of this plausibility, however, is not necessarily an invitation to despair. And it remains so. It simply demonstrates appreciation of the fact that, ever since we realised that the universe is not teeming with humans, we have come to appreciate that the fate of humanity lies in our hands. We may yet prove unfit for this task, but – then as now – we cannot rest assured believing that humans, or something like us, will inevitably reappear – here or elsewhere.

Beginning in the late 1700s, appreciation of this has snowballed into our ongoing tendency to be swept up by concern for the deep future. Current initiatives, such as Bostrom’s Future of Humanity Institute, can be seen as emerging from this broad and edifying historical sweep. From ongoing demands for climate justice to dreams of space colonisation, all are continuations and offshoots of a tenacious task that we first began to set for ourselves two centuries ago during the Enlightenment when we first realised that, in an otherwise silent universe, we are responsible for the entire fate of human value.

It may be solemn, but becoming concerned for humanity’s extinction is nothing other than realising one’s obligation to strive for unceasing self-betterment. Indeed, ever since the Enlightenment, we have progressively realised that we must think and act ever-better because, should we not, we may never think or act again. And that seems – to me at least – like a very rational end of the world.

About The Author:

Thomas Moynihan is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Oxford

This article is republished from our content partners at The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Conversation’s Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges. In generating these narratives, we hope to bring areas of interdisciplinary research to a wider audience.

You can read more Insights stories here.

#featured#space#extreterrestial life#climate change#extinction#fermi paradox#enrico fermi#end of the world

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

That Time $50 Used Apple Laptops Caused a Stampede

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

There’s been a lot in the news lately about kids trying to embrace the weird world of remote learning.

The problem is that the technology, while it’s ready to handle such use cases, isn’t as accessible on a universal scale as it needs to be.

To put it another way: Many school districts, due to budget considerations, still do not give away laptops or tablets to every student in the way that most employers give their employees a laptop (or possibly even a phone). We may believe the children are our future, but good luck getting someone to put in a down payment on a decent computer during a pandemic.

The truth is, though, that this has always been a challenge. The pandemic simply puts it into sharp relief.

Back in 2005, another strange situation put this into sharp relief—although that situation was a bit more manmade.

Let’s go back to the time a school district decided to sell its old iBooks for $50, and the havoc that decision wrought.

23,000

The number of iBooks that Apple supplied to Henrico County, Virginia in 2001, in two separate shipments—one for high schoolers and one for middle schoolers. The plan, which was timed to the 2001 announcement of the white polycarbonate iBook G3 “Snow,” reflected how the county school district, outside of Richmond, was ahead of its time on technology, having purchased the proverbial “laptop for every student” at a time when computers in the classroom for most meant having a well-stocked computer lab. “This is the mammoth–the single largest sale of portable computers in education ever,” Steve Jobs said in a news release at the time. (That said, it does appear that many of the laptops Henrico County received were of the older first-gen iBook style, akin to the original iMac.)

How Henrico County became an iBook innovator before it became a weird footnote

There are two stories about the Henrico County, Virginia school district worth discussing in the context of computing history: The fact that the school may have been one in the first in the country to give a laptop to nearly every student, and what happened to those laptops after the district decided to upgrade.

The first is a story about a forward-thinking district leveraging its largesse for the purposes of equipping its student body for the future. The second, unfortunately, kind of has a Lord of the Flies-type vibe.

Let’s spend a little time talking about the first part, because it really was an innovative program. In 2001, Henrico County entered into a lease-to-own program with Apple, at a cost of $18.5 million, to supply an entire district with laptops. Dr. Mark Edwards, the superintendent of the Henrico County School District, spoke positively of the program when it was first launched.

“The iBook is going to change education in terms of how we teach and learn,” Edwards said in a promotional video for the second-generation iBook. “It’s a tool for collaboration; it’s a tool for invention, for exploration. With that, we developed a vibrant learning community where everyone is a learner and everyone is a teacher.”

The Apple deal had ripple effects—other nearby schools, such as Lindsay Middle School further down Interstate 64 in Hampton, Virginia, also started experimenting with laptops around this time, and other districts across the country started using laptops at slightly smaller scales. Apple’s long-standing push toward education, which helped keep the company afloat even during lean years, seemed like it was getting a few successful hits thanks to the iBook.

(Heck, Apple even developed its own specialized cart for holding the laptops when they were not in use, for schools that didn’t want students to take them home.)

But being an educational setting, there were (of course!) hiccups in Henrico County. While the program drew positive initial headlines, it gained its first hint of notoriety after 50 to 60 students were caught downloading porn on their machines—which (of course!) led to news coverage. One concerned parent let his opinion on the laptops be known.

“We have given them adult equipment—tools,” he said in comments to the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “We have given them to kids who are using them as toys. We’re passing it down the line to kids who aren’t quite ready to use it and they’re going ape.”

And students were attempting to hack into the school district’s systems to change grades.

But Henrico County was willing to correct mistakes as needed. The wired network, which the teachers largely used, was separated from the wireless one that the students did. And in a 2002 article about the laptop program, Henrico schools technology director Mike Smith noted that the district had pretty good content filtering—an upgraded version that was 95 to 98 percent effective. He was a realist about the other 2 to 5 percent.

“The porn industry wants to get to children,” he told the Associated Press in 2002. “As long as that’s the case, you’re never going to be able to block 100 percent of it.”

All in all, pretty much what you would expect for the launch of a laptop program for classrooms in 2001.

$4M

The amount that Dell reportedly undercut Apple in a successful bid in 2005 to win the laptop contract for high-school students that Apple had earned for the iBook sale in 2001. (The middle-school contract largely stayed in place.) While the county said it valued its relationship with Apple, that deal was expensive to keep—and by the time the district started working with Dell, it had spent $43.6 million with Apple over four years.

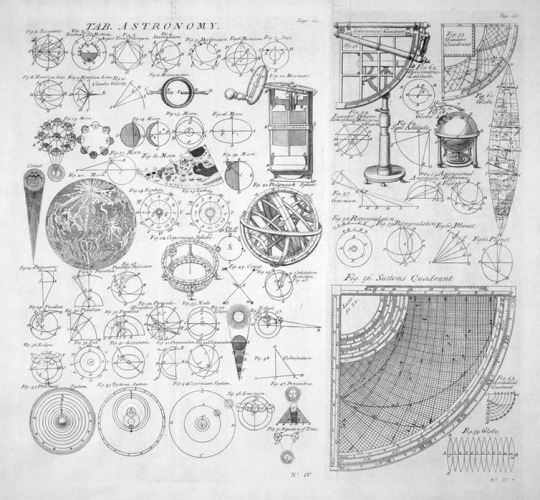

A white second-generation iBook G3. Image: Wikimedia Commons

The day that Henrico County’s wide-scale iBook experiment turned ugly

When it comes to computers in highly organized contexts like education or business, there’s a constant need to upgrade. Generally, the cycle is around three years, maybe longer if your budget is tight.

With Henrico County, the cycle was about four years. I know this because of the strange situation that happened at the Richmond International Raceway on August 16, 2005. On that day, the county held a surplus sale in which the district sold these laptops, which originally went for around $1,400 new, for the bargain-basement price of $50.

The news stories, which got significantly more international press than the original agreement between Henrico County and Apple did, implied that desperation was driving the people trying to get these computers. People got trampled. Some needed medical care. Someone lost their sandal during the melee. One person wet themselves while waiting in line.

But these were $50 wireless-enabled computers at a time when, if you went to the Apple Store, $49 could buy you a mouse. For many families without access to technology, the value proposition spoke for itself.

Still, these laptops were fairly out of date at the time, but not to the point of uselessness. While you could get online with them, they would likely be quite pokey with the latest version of Mac OS X at the time, 10.4 Tiger. And they were soon to be made completely obsolete by the transition away from PowerPC announced two months prior.

And again, these were laptops used by high schoolers in all states of disarray. This may have been the most expensive thing a young teen ever owned, and odds are high that they’re going to break it. If a kid got a hold of a lighter and used it to melt down some of the plastic, or decided to draw on the back with a permanent marker, all that stuff was still there.

But they were computers, and they worked. And for some people, that’s all that mattered.

Now, surplus programs are generally not promoted very much, are low-key affairs, and are ways to get a computer on the cheap.

But that’s not what happened in Richmond. It was announced publicly, including on the school district’s website, and promoted to the media. A passage from the announcement:

A unique opportunity is available from Henrico County Public Schools. Used Apple iBook laptop computers will be on sale for $50 each, with a one-per-person limit. The one-day sale will be held Tuesday, Aug. 9 from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m.

One thousand laptops will be sold at the school warehouse—361 Dabbs House Road beside the Eastern Government Center—on a first-come, first-serve basis. Only cash or checks will be accepted.

The white, Power PC 750s with 12-inch screens have 320 megabytes of memory, Mac OS 10.2.8, and AppleWorks 6.2.9.

The public announcement that the district was getting rid of a thousand iBooks created a frenzy, one that spread far beyond the school district’s borders and hit the international news. For one thing, Apple blogs drew attention to the event, and Apple fans are crazy, so many of them legitimately discussed traveling long distances to get a $50 laptop.

While the school district managed the devices while they were still in the classroom, the Henrico County government handled their sale and disposal, and did so in a fairly haphazard way.

Trying to find images or video of this thing that happened was surprisingly hard; I couldn’t even find video of the incident. Here’s a contemporary screenshot of a news report at the time. Image: Internet Archive

Case in point on this issue: A quote from a guy who was beating people with a lawn chair in an effort to protect his spot in line.

“I took my chair here and threw it over my shoulder and I went, ‘Bam,’” the guy said. “They were getting in front of me, and I was there a lot earlier than them, so I thought that it was just.”

(That quote was enough to draw the attention of famed Microsoft blogger Raymond Chen, who deadpanned of the man’s claim, “That’s one of the guiding principles this country was founded on.”)

If anything, the overwhelmed reaction to the iBooks reflected something basic: While Henrico County did its students a lot of good by purchasing these laptops, and put in a lot of work to acquire them and run its program, the program did not go far enough. The school district spent tens of millions of dollars on these machines, and when they were spent, the district tried to extend their life in the most haphazard way possible.

The district didn’t even bother to limit the sale to county residents until it started getting attention on Apple blogs. And by then, the buzz around the selloff all but guaranteed a bad result.

Looking at it now, the tragedy of the situation is much more clear: There were lots of people in its community that could use these machines, and even selling them for cheap left people out. A quote from Paul Proto, the director of general services for Henrico County, seemed telling to a degree, a general misunderstanding of the situation.

“It's rather strange that we would have such a tremendous response for the purchase of a laptop computer—and laptop computers that probably have less-than-desirable attributes,” Proto said to the Associated Press. “But I think that people tend to get caught up in the excitement of the event—it almost has an entertainment value.”

Yes, that is probably the most common, least charitable interpretation of what happened that day. But on the other hand, what if that value was handed off to people who needed it the right way, say, through a nonprofit like Goodwill?

This was the age before the smartphone, when real internet access required a computer. I imagine some of these people just wanted a way to get online, or at the very least, an extra machine to tinker with or hand off to their kids.

One has to wonder if we are too quick to throw off good technology just because it’s outdated.

3.8%

The approximate value that the iBook G3 devices sold by Henrico County kept over four years, based on their $1,299 list price in 2001 and $50 selling price in 2005. (One presumes that Apple gave the school district a discount.) That means that someone who started high school in Henrico County in 2001 saw the laptop that got them through four years of school lose 96 percent of its value through normal use. Can you imagine an equivalent device depreciating at the same rate today?

We’re 15 years past the Henrico County stampede, with a bigger need for older devices than ever. And we’re struggling to manage them correctly

Part of the reason I found myself reflecting on this story was a discussion I had with a Twitter pal of mine, John Bumstead, a recycler and reseller who specializes in old Apple equipment through his company RDKL, Inc.

Bumstead often sees old machines like vintage iBooks and MacBooks pass through his purview, many of which are good enough to reuse. But for many recyclers, there is often a cost/benefit equation at play. The way he put it to me involved electric drills getting taken to iBooks. At some point, the value equation may mean even working machines find their way to the scrap heap—because its raw materials are worth more than the machine itself.

“Recyclers have the unenviable task of deciding the fate of millions of devices—scrap it, or if it’s valuable enough as what it is (a usable computer), sell it to those who would repair/refurbish,” he explained in an interview. “A laptop has about a $10 scrap value, meaning if its parts are broken down (plastic, board, screen, battery, metal), the material can be sold for about $10.”

Perhaps the saddest examples, at least on the Apple side, are the “cloud-locked” machines, which are otherwise perfectly functional but made useless by anti-theft functions contained in iCloud. Many customers get rid of their devices without turning off this functionality, and the result is that phones, iPads, even modern laptops are of no resale value beyond the worth of their metal.

During normal times, stuff like this is already bad enough. But we’re facing a historic need for computers—particularly those just powerful enough to get a 7-year-old through a virtual learning session while working remote. And computing disparities can remove learning gains. While many schools have options like Chromebooks and iPads available, many others do not.

Bumstead notes that, as a non-certified refurbisher, he’s often not put up against the more stringent standards for certification. While it limits his access to machines from more traditional supply chains, in a way, this has put him in an unusual situation where he ends up taking the machines deemed not good enough for other recyclers—often polycarbonate MacBooks that can still access the modern Internet and still work just fine with a little TLC, but are more than a decade past their sell-by date. (The video above explains his POV on this situation.)

“I’ve sold hundreds in the last few months to people using them for school. And the irony is that they came from schools, were retired to recyclers, became half-destroyed in the process … then I pieced them back together and sold them back into circulation for students of the schools to use,” he said. “It begs the question: Why didn’t the schools just continue using them? Or better yet, why didn’t they give them to students directly?”

As for the reaction Henrico County saw for its iBooks in 2005? Bumstead gets it, based on what he sees in the modern day. For many buying these machines, the need for technology often outpaces their knowledge of what makes a good gadget for their given situation. While the technically inclined might find value in the dumpster, expectations need to be set when it comes to things like laptops with working webcams and functional Wi-Fi.

“People simply don’t know what they are buying; they are simply mesmerized by the Apple symbol,” he said. “And unfortunately at a time like this, that probably leads to them getting ripped off.”

I don’t talk about this much, but there was a brief period of my adult life where I didn’t have a working home computer. It was maybe about four or five months.

And the reason that it happened comes down to a known GPU fault in the iBook G4 I had at the time. The problem hit during the worst possible time: In early 2006, amid a transition period of my life, after I had left a bad roommate situation. I was broke, and I had recently moved halfway across the country, so I got rid of a bunch of stuff before I left town, including my old desktops. Student loan bills were starting to really hit for the first time. And while I had a good job in newspapers, it was simply going to take some time to raise the money I needed to replace the dang thing.

If I had technical knowledge at the time, I perhaps could have fixed it. But the laptop was second-hand and didn’t have AppleCare, and I was hundreds of miles from the nearest Apple Store. So, instead, I kind of had to live without it. I stayed longer hours at work to handle computing-related things, and went home, and just watched Stephen Colbert and the series finale of Arrested Development. (Which, famously, ran against the Winter Olympics.)

And because I was a sucker, when I finally saved up enough money, I bought the exact same machine—this time, however, with AppleCare.

I’m sure I joked about the iBook riots online in 2005. Heck, everyone did. Had this happened when Twitter was around, it potentially could have been a far bigger pop-culture moment than the footnote it became.

But I kind of look back at this time, knowing what I know about disparities and access, and I wonder if Henrico County—despite being visionaries around the role of technology in classrooms—realized after the fact how raw a deal it was giving to those in its community who were living without home access to modern technology.

It could have been a great moment. Instead, it was a disaster.

That Time $50 Used Apple Laptops Caused a Stampede syndicated from https://triviaqaweb.wordpress.com/feed/

0 notes

Text

The Murderess from the Grunewald (8): Claire’s story (2)

“Der Reichstag” - Seat of the German Parliament * Picture by Jürgen Matern [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Previoulsy

Six months ago - First Attorney’s Visit in Prison (3)

“So your husband had bought a house in prestigious Grunewald colony …“

"Yes, Frank was very proud that he had managed to acquire a house in this prosperous district. The ‘best district’ of Berlin, as he emphasized again and again. Of course he knew the history of this place. When we were still in Boston he had only told me that he had acquired a large house in a good district of Berlin for our future family. Honestly, I didn’t care that much. I had lived in so many places on this earth and under so many different circumstances with my uncle Lambert … The only important thing for me was that we had a good place to live and see our children grow up in. On the flight to Berlin he told me about the history of this place.”

"Otto Prince of Bismarck, the first chancellor of the German Empire, himself made sure that a large part of the forest Grunewald was sold by the Prussian State to the Kurfürstendamm Society, a banking consortium, in 1880. The aim of the company was to build a more elaborate residential district based on the model of the very successful villa colonies in Alsen and Lichterfelde, thus creating what was later called 'the millionaire colony Grunewald’. Whoever lived there then, had made it. That’s how it is still today. Several states have their embassies there and also maintain residences for their ambassadors. Great Britain and Ireland for example … “

He smiled.

"I know. Frank told me that on the flight from Boston to Berlin. And, of course, celebrities lived and live there too - Ferdinand Sauerbruch, Lyonel Feininger, Hildegard Knef, Isadora Duncan, Max Plank, Judith and Michael Kerr.”

"Did he also tell you that Heinrich Himmler lived there?“

Claire turned white.

"No.”

"I knew it,“ Jamie thought, "one can’t be proud of that.” To Clair he said:

"Well, it doesn’t matter. Please continue.“

"As I said, the house we moved into was one of the so-called 'smaller villas’. Nevertheless, it was huge in my opinion. It had three floors. On the ground floor, next to Frank’s library and his study, there were several large rooms. And of course the kitchen with its own large pantry. We mainly used these rooms when guests came. On the second floor was our bedroom, which had a dressing room. It was like a big, walk-in closet. There were four other rooms, which were a bit smaller. The largest of these rooms we used as a living room. In another, I set up a small room for myself.”

Jamie looked up from his notebook.

"Why did you need a private room?“

"I simply felt the need for a place that only belonged to me. I wanted to be able to sew without disturbing Frank. While living in Boston, I could only do that when he was away from home. He always felt disturbed by the sound of the sewing machine. I also wanted to have a place where I could keep a diary, a place where I could place my pictures on the walls.”

W. Ulbricht im Tal der Könige, Ägypten * Picture: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-D0227-0053-004 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons

Jamie looked up from his notes again. His face showed astonishment.

"Why couldn’t you hang your pictures somewhere else in the house?“

"Frank was ... against it. I have many pictures of myself and my uncle Lambert, of the places we visited during his expeditions and excavations. Mostly … unconventional pictures. Frank said that they would not fit into the overall picture of our house. After all, we would have guests, colleagues from the university, and my pictures could raise questions … ”

"What questions?“

"Questions about my 'unconventional past’, my 'unconventional upbringing’, my ‘unconventional education’ … Frank did not want that to be known to his new colleagues.”

Jamie rolled his eyes.

"When he talked to his colleagues, however, my doctor’s degree always came quickly to his lips … But he always added that I would not work at the moment because we wanted to start a family.“

"What happened then after you arrived in Berlin?”

"As I said, the arrangement of the house took a lot of time, especially since I had to do most of it alone. Frank, when he was in Berlin to buy the house, had also commissioned a company to paint and decorate it. He had also brought a floor plan, so that we planned the layout and furnishing of the rooms while still in Boston. But with all the boxes of our belongings … I was alone. Frank started working at the university the week after we arrived. He had little time to help and if he had it was only on the weekends. In addition, one of our containers arrived late. It took about two months for us to get properly set up.“

"And then?”

"Well, the first months were good. I took care of the house, we tried to get pregnant, … Frank got to know his colleagues, we went to parties … we also took some trips. Although Frank liked to spend the weekends at home - at least at that time - he was well aware that it was not good if we didn’t do anything together. We visited the Reichstag and boarded the Reichstag dome. Of course, Frank knew everything about the history of the building. When we arrived at the top of the dome, he was talking about the Reichstag fire in 1933 and what consequences it had for the country. Some seniors who stood beside us started a conversation with Frank. They were thrilled to be talking to a real 'Herr Professor’ … and obviously, it flattered Frank that he immediately had an audience. After a few minutes, I took off from Frank and the seniors and explored the dome on my own. The architect’s idea that the glass dome over the Parliament should urge the Members of Parliament to be more transparent towards the citizens impressed me. When Frank’s seniors had said goodbye, I told him about it. But he found this idea 'unrealistic’. Politicians would do what they wanted … no artistic symbol would have the power to change that.“

Blick durch die Kuppel des Reichstages in den Abgeordnetenhaus des Deutschen Bundestages (View through the dome of the Reichstag into the House of Representatives of the German Bundestag) * Picture: By Another Believer [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

She sighed, then she looked down and - for a moment - and said nothing.

"Still, these months were some of our better times. We visited Charlottenburg Palace, the TV Tower, the Gendarmenmarkt, the German and the French Cathedral. In our second summer in Berlin, we even made a river cruise on the Spree. I remember that well … and gladly. It was a very nice experience. In the evening we were eating at the Corroboree. That is an …”

"… Australian restaurant in the Tiergarten district. I know.“

Jamie smiled.

"You know it?”

"Yes, a colleague of mine, Ben Hombach, wanted to know how kangaroo tastes. He invited me there.“

"And? Did you eat kangaroo?” she challenged him.

Jamie decided to play along. He was sure that they would have to address many unpleasant things in their conversations. Why shouldn’t he give her a moment of relaxation?

"No, I opted for a steak after all. I like kangaroos too much to have one of them on my plate. But please continue. “

"As I said, this time was positive. We hardly argued and when, it was never a big fight. It was always forgiven quickly and forgotten. In between, we visited Frank’s cousin in England or Alex came to us. Mutual visits to Christmas were … obligatory. Frank enjoyed these stays in England very much. Although there is a great deal of English culture in Berlin - and even some English restaurants … ”

"Like the ‘East London’, for example.“

"Were you there with your friend Ben too?”

"No, not yet and to be honest, due to my background I prefer the Scottish Pub in Lichterfelde. They have over 800 varieties of whiskey on offer.“

"I would be glad if I had one whiskey now.”

"Alcohol is ….“

”… forbidden in prison. I know. Where was I? Oh yes, family visits. Alex, Frank’s cousin, also liked to come to Berlin. I think it was the third year after our move that he visited us on the occasion of my birthday. Frank invited us on a trip to the Museum Island. We visited the New Museum with the Nefertiti hall. That was a really special event for me. My uncle Lamb had often told me about her bust. He had been to Berlin several times and had seen her. However, that was long before he became my guardian and long before the Egyptian queen got her own room in the renovated Museum. So my first visit there was a very special experience. However, the mood was soon to change. On Saturday that week we had guests to celebrate my birthday. Several of Frank’s colleagues with wives or girlfriends were there, but I also invited a few people whom I had met in the meantime.“

"So you also had new contacts on your own?”

“A few, yes.”

“Tell me about it!”

“Well, you certainly know that years before you have a baby you have to register for a kindergarten place. Of course we did not want any kindergarten for our child, but an English speaking one. So we visited our chosen kindergarten and had a conversation with the headmistress, Mary Hawkins. She was immediately sympathetic to me, and after meeting her in the city a few weeks later, we stayed in touch and became friends. Next to our house in Grunewald lived an elderly lady, Glenna Fitz-Gibbons. Her husband, who died a few years ago, was an English officer stationed with some NATO unit. She herself has worked for the British Embassy until she retired. Over time, we developed a very good relationship. We started talking about the flowers that I planted in our garden and from then on we met regularly for tea. One day Frank brought home a young colleague who had just moved to Berlin with his wife. His name is Roger Wakefield. He is a nice guy, very helpful and friendly. He and his wife Fiona have a little son, named Colin. They are very … conventional … if you understand what I mean. Nevertheless, I met with Fiona every now and then.”

"She is not as unconventional as you?“

Claire smiled, but that smile did not last long.

"I had invited these three women. Oh, and a nurse whom I knew from the Benjamin Franklin Hospital in Berlin, or better, trough a friend from Boston. Her name is Gellis Duncan. She is Scottish but lived and worked in Boston for several years, at the same hospital as my friend Joe Abernathy. She had a relationship with a doctor and when he was called to Berlin, she went with him. Joe wrote me and asked me to take care of her. She did not know anybody in Berlin. I made an appointment with her and showed her the city. We stayed in contact and met often.”

River cruise ships on the Spree / Berlin, the Bode-Museum (with dome) at the right side marks the Entrance to the Museum Island * Picture: by Bode Museum [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons

"Did you also have any contacts or friendships with 'locals’?“

Claire rolled her eyes. Then she leaned forward and whispered:

"Yes, but do not pass it on!”

Jamie leaned over and whispered:

"Promised. Tell me more!“

"Well, I got to know one of the librarians of the district library when I registered there. Her name is Suzette Fournier.”

"But that sounds French.“

"She comes from one of the Huguenot families who fled France after the persecutions three hundred years ago. Her family has kept the custom of giving the children French names and they also tend to cultivate some French customs. But Suzette is already very German. You must see her when she drinks beer. But … yes its true … most of my contacts and friendships to ’locals’ came after I moved to my present apartment … after Frank’s death.”

"How did your husband relate to these contacts or friendships you mentioned?“

"He was not against me meeting with those women, but after my birthday party he said that next time I should invite them separately. These women wouldn’t be the right people to have when his colleagues and their wives were our guests. I was angry, but I swallowed it and later I just didn’t talk about it anymore and from our fourth year it got harder and harder with us.”

Jamie looked at her and took a deep breath. Then he said:

"I know, Claire, it’s certainly hard for you … but we need to discuss that. We do not know what this … witness …. and your husband’s cousin will tell the court … we have to be prepared.“

She nodded and he saw her body stiffen.

"For the first two years, everything was reasonably normal. But when I did not get pregnant in the third year … Frank became more and more angry. He did not show it at first, but I did notice the anger seething inside him. I tried to comfort him, to give him hope …. ”

"Did you suggest to him that you both could undergo medical examination?“

"No! I had thought about that, but no. I … I was worried that … how he would react.”

Claire went silent for a moment. Her face showed signs of despair.

"In Boston … I once addressed the issue of adoption …“

"How did her husband react?”

"With a tantrum. He … he said, he only wanted to accept a child of his own blood.“

"Did you fear that you husband would become violent?”