#stela of taimhotep

Text

The Lament of Taimhotep

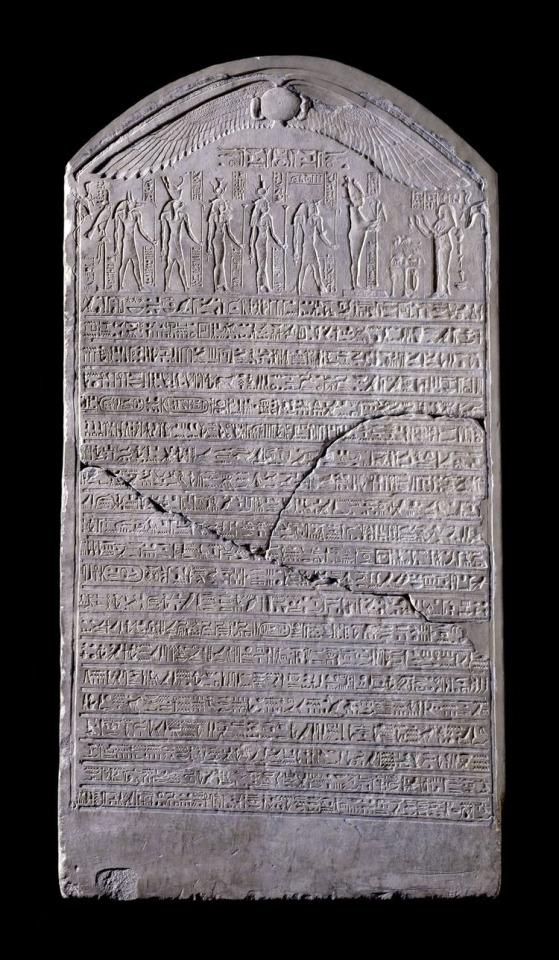

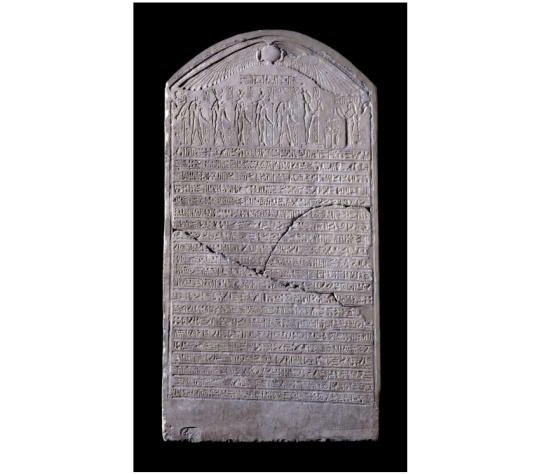

The stela of Taimhotep. Ptolemaic Period (42 BCE). British Museum EA147

On Taimhotep (73-42 BCE) and her funerary stela see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taimhotep

After the narration of her life (her marriage at the age of fourteen to Psherenptah, the high priest of Ptah in Memphis, the birth of three daughters by him and, after the intervention of the deified Imhotep, the birth of the long-awaited son), Taimhotep laments her untimely death and more generally the situation of the dead, in perhaps the most pessimistic funerary text in the ancient Egyptian literature.

The translation of the part of the stela with Taimhotep’s lament that I reproduce here is from Miriam Lichtheim Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol. III The Late Period, pp 62-64:

O my brother, my husband,

Friend, high priest!

Weary not of drink and food,

Of drinking deep and loving!

Celebrate the holiday,

Follow your heart day and night,

Let not care into your heart,

Value the years spent on earth.

The west, it is a land of sleep,

Darkness weighs on the dwelling-place,

Those who are there sleep in their mummy-forms.

They wake not to see their brothers,

They see not their fathers, their mothers,

Their hearts forgot their wives, their children.

The water of life which has food for all,

It is thirst for me;

It comes to him who is on earth,

I thirst with water beside me!

I do not know the place it is in,

Since (I) came to this valley,

Give me water that flows!

Say to me: “You are not far from water!”

Turn my face to the northwind at the edge of the water,

Perhaps my heart will then be cooled in its grief!

As for death, “Come!” is his name,

All those that he calls to him

Come to him immediately,

Their hearts afraid through dread of him.

Of gods or men no one beholds him,

Yet great and small are in his hand,

None restrain his finger from all his kin.

He snatches the son from his mother

Before the old man who walks by his side;

Frightened they all plead before him,

He turns not his ear to them.

He comes not to him who prays for him,

He hears not him who praises him,

He is not seen that one might give him any gifts.

O you all who come to this graveyard,

Give me incense on the flame,

Water on every feast of the west!

The scribe, sculptor, and scholar; the initiate of the gold house in Tenent, the prophet of Horus, Imhotep, son of the prophet Kha-hapi, justified, has made it.

(Imhotep, son of Kha-hapi was the scribe and sculptor who composed the text and designed the stela -Lichtheim, op. cit., p. 65, note 23).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stela of Taimhotep

4/19/17

It starts out talking about her husband. She tells him not to worry that she is dead. This is the best part of the poem. The bulk of it is her talking about how thirsty she is or might be. She is asking people to help her not to be so thirsty. This contradicts the earlier part where she tells her husband not to worry that she is dead. If someone was going to quench her thirst, it should probably be her husband.

0 notes

Text

Italian- British Egyptologist Luigi Prada on divination in ancient Egypt (with a reference to Herodotus as source on this subject)

“Dreams, rising stars, and falling geckos: divination in ancient Egypt

Moving on from a neglected discovery by the EES, Luigi Prada leads us into the little-known world of ancient Egyptian divination and its practitioners. In addition to popular techniques such as dream interpretation and astrology, we discover that the ancient Egyptians enquired after their future also through the behaviour of animals, the occurrence of thunder, and several other natural phenomena.

Between 1964 and 1976, the excavations of the Egypt Exploration Society at the Sacred Animal Necropolis in North Saqqara produced such an overwhelming wealth of finds that scholars are still busy researching and publishing them today, half a century later (see Heinz and Vander Wilt in EA 49). But even when promptly published, some of the results of this fieldwork have remained virtually unknown outside specialist circles. This is the case with the archive of Hor of Sebennytos, an Egyptian priest who lived in the second century BC ...Like several of his fellow priests, one of Hor’s leading interests and activities was oneiromancy – that is, dream interpretation.

Dreams were always an object of fascination for the ancient Egyptians (and many other ancient societies as well). In the liminal dimension of slumber, it was believed that direct communication with the divine and the netherworld would be possible. A particularly famous example of such a divine encounter is narrated in the so-called Dream Stela of Thutmosis IV (c. 1400 BC), which still stands between the front paws of the Great Sphinx at Giza... This Eighteenth Dynasty-inscription tells how the young prince Thutmosis, having fallen asleep by the monument, sighted in a dream the god Harmakhis-Khepri-Re-Atum, with whom the Sphinx was identified at the time. The god asked the prince to clear his statue of the sands that had covered it and restore it to its ancient splendour, in exchange for which he would grant him the throne of Egypt. Clearly a piece of post-eventum political propaganda, this stela nevertheless exemplifies the special regard in which dreams were held.

Dream Stela of Thutmosis IV. In a specular scene above the hieroglyphic text, the king gives offerings to the Sphinx, identified with the god Harmakhis.

It is particularly in the Graeco-Roman Period, however, that we witness an exponential rise in the textual and material evidence related to dreams. Accounts of dreams were increasingly recorded on papyri or ostraca, as in the case of Hor of Sebennytos’ archive. Dreams still featured in formal texts as well, such as the exquisite funerary stela of Taimhotep in the British Museum... The wife of Pasherenptah, High Priest of Ptah in Memphis during the reign of the famous Cleopatra VII, Taimhotep recounts in her autobiography how, after having three daughters, she and her husband prayed to Imhotep, the son of Ptah, that a male heir be granted to them. The god listened to their prayers, appearing in a ‘revelation’, asking for works to be carried out in his temple in returnfor his intercession.

Ostracon Hor 3 verso. Line 22 includes the first mention of Rome in an Egyptian text, with regard to the Roman ultimatum that put an end to the Syrian invasion of Egypt in 168 BC

Focus: Hor of Sebennytos Hor of Sebennytos was a priest active in the Memphite necropolis in the first half of th e2nd century BC. His archive, published in 1976 and consisting of approximately 70 ostraca – i.e. inscribed potsherds – written mostly in Demotic, gives an account of his daily occupations and preoccupations. The topics dealt with in these texts, which are mainly personal notes and drafts of documents, include the cult of the ibises and their mummies, oracles and dreams. Some of them also have historical relevance, as they relate important political events seen from a humble priest’s perspective. Such is the case of text no. 3, where Hor records a prophetic dream that he had at the time of the Sixth Syrian War (170–168 BC), when Egypt was occupied by the enemy forces of Antiochus IV, King of Syria, and the Ptolemaic dynasty seemed to be on the verge of collapse. In this dream, Hor saw that, despite all odds, Egypt and the Ptolemies would be saved – as, in fact, they were in the summer of 168 BC, when Antiochus peacefully withdrew from Egypt after receiving an ultimatum from Egypt’s (then) mighty ally: the Roman Republic.

But the importance of dreams was not limited to those featuring divine epiphanies. Dreams of a trivial or even haphazard content could also be considered potential vehicles of hidden messages about a person’s future. An entire science was developed for interpreting such dreams and unravelling their hidden messages. To call dream interpretation a science may sound at odds with modern Western concepts of superstition, but applying our modern views to the study of ancient Egyptian oneiromancy would be grossly inappropriate. Very much like medical or legal texts, dream (and, generally, divination) books belonged to scribal and temple libraries, being a prerogative of the learned. Dream interpretation handbooks, also known as oneirocritica, are the best- and longest-attested type of divinatory literature from Egypt. The earliest known such manuscript is P. (= papyrus) Chester Beatty 3... Now in the British Museum, it comes from the village of Deir el-Medina and dates to the time of Ramesses II (13th century BC). It originally belonged to the scribe Qenherkhepshef, whose preoccupations with sleep are further attested from other items once in his possession... Each line of this manuscript contains a description of a dream with its defining features and its interpretation, setting out what would befall the dreamer or his relations.Thus, in its col. 2/21, we read: ‘If a man sees himself in a dream eating donkey-meat: good, it indicates his promotion’. Almost one and a half millennia later, in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, dream books still thrived, and are attested in larger numbers than ever. Handbooks of the kind that Hor himself may have used are now divided into a myriad of chapters, each dedicated to a different topic: dreams about sex, about drinking, about animals... – basically any topic one could think (and thus dream) of. Within each chapter, individual dreams are still listed line by line, followed by their interpretation.Thus, within the section discussing sex-related dreams in P. Carlsberg 13, a manuscript from 2nd century AD- Tebtunis, a town in the Fayum,one may find: ‘If (a woman dreams that) a snake has sex with her: (it indicates that) she will find herself a husband. (But) if she is (already) married, she will become ill’ (frag. b, col.2/27–28)

Stela of Taimhotep, BM EA 147. Line 8 gives the reason for Taimhotep’s distress and her praying for Imhotep’s intervention

Below: Papyrus Chester Beatty 3, BM EA 10683. Colums 8-11 recto: note the elaborate layout of this dream book

Bottom: funerary headrest of Qenherkhepshef, BM EA 63783. The object’s funerary use, associating slumber with death, clearly transpires from the hieroglyphic inscription, which mentions “a good sleep in the West (=the netherworld) and is surrounded by apotropaic figures.

But how did this science operate? How are the dreams and their respective interpretations matched? A rationale is indeed present, though at times not easily detectable. In the dream quoted above, the explanation is based on a (wholly Freudian!) association, assimilating the snake with a phallus and, therefore, with the image of a male partner. As for the dream from P. Chester Beatty 3, the coupling is instead based not on analogy of image or content, but of sound – namely, on wordplay as the words for ‘donkey’ (Egyptian ΄a΄a) and ‘promotion’ (Egyptian s΄a΄a) sounded alike

That divination was a particularly serious matter in Graeco-Roman times is also suggested by the concrete business that stood behind it. Not only Egyptian priests like Hor were active as dream interpreters: in the same area of Memphis, Greek-language soothsayers, too, were at work, interpreting dreams and advertising their skills to the increasing number of Greek residents in Egypt. One, who probably lived shortly before Hor, left behind what we may call his own ‘shop-sign’, where, in Greek, he boasts that ‘I interpret dreams, having (this talent) as an order from the god. With good luck! This interpreter comes from Crete’...

Business sign of a Cretan dream interpreter, CGC 27567. The decoration mixes Egyptian and classical styles. Underneath the Greek text is an image of the Apis bull, worshipped in the Serapeum at Saqqara, just a short distance from where this item was discovered.

But divination was far from limited to oneiromancy. In the fifth century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus included divination amongst the inventions of the Egyptians, saying that they had discovered ‘more omens than all other peoples’ (II.82). He was not exaggerating: many other mantic arts were practiced by the Egyptians since at least the New Kingdom, with their number and popularity steadily increasing in Graeco-Roman times. For instance, from Ramesside Deir el-Medina and now preserved in Turin’s Museo Egizio, we have fragments of a manuscript that illustrates the practice of lecanomancy (GCT54065). This is a way of foretelling the future that uses a dish or bowl filled with water. As described in the papyrus, oil was poured on the water, and the resulting patterns and shapes formed by the floating blobs were the signs to be interpreted. Remarkably, both lecanomancy and dream interpretation were already associated with Egypt by other ancient civilisations, and are for instance featured in the Biblical story of Joseph and his brothers.

Another Nineteenth Dynasty hieratic papyrus, also from Deir el-Medina and now in Turin (CGT 54024), deals with meteorological omens, including thunder – a divinatory technique known as brontoscopy.The same art was still practiced a millennium later, in Ptolemaic times: an unprovenanced Demotic papyrus in the Cairo Egyptian Museum (inv. RT 4/2/31/1-SR 3427) lists and interprets very similar omens, also in connection with the occurrence of a ‘voice-of-Seth’ (as thunder was called in Egyptian). One passage mentions perhaps the oddest scenario: thunder accompanied by shower sof… frogs (col. 1/11: ‘if a voice-of-Seth occurs and it [literally, the sky] rains frogs…’) – not entirely impossible in the wake of tornadoes and similar violent weather events!

Amongst the various branches of divination and equal only to oneiromancy, pride of place was certainly given to astrology – a relative late comer in the world of Egyptian divination, following increased contacts with the Near East in the 1st millennium BC, particularly after the Assyrian and Persian invasions of Egypt. From the Graeco-Roman Period, a wealth of Demotic material, still largely unpublished, includes various types of documents related to astrology. First come astrological handbooks, which fall into two categories: manuals of universal astrology, interpreting the relative position of the celestial bodies in order to foretell the fate of entire countries and peoples; and handbooks of individual astrology, foretelling a person’s future based on the position of the celestial bodies at their time of birth, with respect to various divisions of the sky (including our twelve zodiacal signs, as well as other partitions known a sastrological ‘houses’). Thus, in one of the manuals of the latter type, the Demotic P. Berlin P. 8345 (from the Fayum, 1st or 2nd century AD), we can read, with regard to a man who was born ‘when Venus was in the descendant: he will quarrel much with a woman; a nasty reputation will come to him…’ (col. 2/5–7). Through such handbooks, the ancient Egyptian priests could cast life horoscopes for their customers. Working papers of these astrologers, i.e. jottings on ostraca and scraps of papyrus containing horoscopes, also survive in good numbers.

Yet another type of text, planetary tables,were essential to cast any horoscope – a kind of text that, from our modern perspective,we would classify as astronomical, rather than astrological. Such tables were painstakingly accurate numerical records of the exact dates when the celestial bodies entered specific zodiacal signs, and could extend over very long periods, years and years into the past, so as to allow an astrologer to look up the position of the planets at the time of their customer’s birth, no matter how far in the past this was, and thus cast their horoscope. A fine example are the so-called Stobart Tablets...,probably from Thebes and dating to the mid-or late second century AD. Now in the World Museum, Liverpool, they are thin wooden tablets covered with a layer of gesso and inscribed with Demotic, containing exhaustive information about planetary movements spanning the reigns of the emperors Vespasian (69–79 AD) to Hadrian (117–138 AD).

One of the Stobart Tablets, M 11467d recto. Red headings indicate years (here, regnal years14–17 of Hadrian, i.e.129/130–132/133 AD).Following each heading are five cells, one per planet, separated by horizontal lines, listingt he date (month and day) on which the planet in question entered the different zodiacal signs during that year. In the first two columns (fromt he right, as Demotic reads right to left),after ‘regnal year 14’(col. 1, line 16), we find sections for Saturn (lines 17–19), Jupiter (lines 20–22), Mars (lines 23–33), Venus (col. 2, lines 1–16), and Mercury (lines 17–30)

This brief introduction to ancient Egyptian divination cannot be considered complete before at least one further branch of divination is mentioned: that dealing with so-called animal omens, for which Demotic handbooks are attested specifically from the Roman Period. In this case, the omen to decipher was the behaviour of various animals – in most cases, their interaction or physical contact with a human observer, who was the target of the omen. The animals in question could be highly disparate, ranging from cows to dogs, from scorpions to shrewmice. Most typically, however, small animals seem to have been the favourite subject of this genre, for the simple reason that daily contact with creatures such as shrewmiceand the like, found in all Egyptian houses, wouldhave been the norm for everybody.

Just like astrology manuals, animal omen handbooks can also be roughly classified into two groups: those divided into chapters, each discussing omens pertaining to a different creature, and those entirely dedicated to one single animal. To the latter group belongs the fascinating Book of the Gecko thus titled in the original papyrus preserving it, P. Berlin P.15680, possibly from the 1st-century-AD Fayum. Geckos were as common in ancient Egypt as they are in the region today, where they can often be observed crawling on walls and ceilings.These lizards are such extraordinary climbers that their accidental fall must surely have caught the ancient Egyptians’ attention – to the point of being considered an omen. This is why all lines of the Book of the Gecko with the phrase ‘if it (i.e. a gecko) falls’, followed by the specifics of its mishap. These can include a woman’s body parts onto which the gecko would land, systematically listed from head to toe. Thus we read:

If it falls on her right breast: her heart will be greatly distressed, she should entrust herself to the god. If it falls on her left breast: she will be pleased within her family, many sons will be born to her. If it falls in between her breasts: she will fare very well, something from Pharaoh will quickly reach her (col. 2/2-4))

The handbook further proceeds by describing more elaborate situations in which a gecko may unwittingly partake, such as: ‘If it falls on a woman who is having sex: she will rejoice, she will rejoice anew over this same year’ (col. 3/21).

Many more divinatory arts are attested fromancient Egypt – far more than could be presented in this short article. What this brief introduction will have hopefully achieved is not only to introduce the reader to the world of ancient Egyptian divination, but also to give a better awareness of how much we are still discovering and learning, to this day, about the ways of ancient Egyptian life. Be it by excavations like those conducted by the EES in Saqqara, leading to the unearthing of the archive of Hor, or the product of “museum archaeology”, bringing about the publication of papyri previously lying neglected in museum collections, these discoveries are unlikely to cease any time soon, further deepening our understanding of ancient Egypt’s past through the way its inhabitants tried to read their own future.”

Source: https://www.academia.edu/33299952/Dreams_Rising_Stars_and_Falling_Geckos_Divination_in_Ancient_Egypt

Dr Luigi Prada is Assistant Professor in the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History at Uppsala University. His current project focuses on schooling and education in Ancient Egypt, with particular focus on the Ptolemaic and Roman periods. His other research interests include ancient divination (specifically, dream interpretation), bilingualism, and demotic language and literature. He participates in fieldwork in both Sudan and Egypt, where he is Assistant Director of the Oxford University Epigraphic Expedition to Elkab. . Check out his work here.

Source: https://papyrus-stories.com/luigi-prada/

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Funerary Stela of Taimhotep (73-42 BCE)

Funerary Stela from Saqqara belonging to Taimhotep, wife of Psherenptah, the High Priest of Ptah of Memphis. Reign of Cleopatra VII (51-30 BC)

Repository: London: British Museum

Source: http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/fisher/record.html?id=FISHER_n2003080054

Stela BM 147 has a depiction of Taimhotep worshipping Sokar-Osiris, Apis, Isis, Nephtys, Horus, Anubis and a symbol of the West. The text on the stela is 21 lines long and tells of Taimhotep's life. She was born in the 9th regnal year of Ptolemy XII Auletes; her father was apja Khahapi, a priest of Ptah, Min, Khnum-Ra and Horus, her mother was Herankh, a musician of the Ptah temple. She had a brother, High Priest Pasherienamun I and a sister called Taneferher, who married each other; a further possible brother is the scribe Horemhotep.[7] In the 23rd regnal year, at the age of fourteen (July 25, 58 BCE)[8] she married the High Priest of Ptah, Pasherienptah III, and had three daughters and a son by him. Her children are named on the stela BM 377: the son Imhotep-Pedubast and the daughters Berenike, Herankh (nicknamed Beludje) and Kheredankh.[9] It is known that Kheredankh was not her daughter, as she was born to Pasherienptah seven years before his marriage to Taimhotep, and her name was inscribed on the stela erroneously in place of her actual third daughter Her'an (nicknamed Tapedibast), whose name can be found on another stela of her father (Ash. M. 1971/18).[8]

After the birth of her third daughter she prayed to Imhotep, an Old Kingdom sage who was deified in later centuries, for a son. Her prayers were answered and her son was born in 46 BCE, the 6th regnal year of Cleopatra VII. Taimhotep died four years later.[4][5] On her stela Taimhotep laments her untimely death and asks her husband to enjoy life while he can; this is the longest ancient Egyptian text of this kind. From her husband's two stelas it is known that he survived his wife by only one year.[4] Their son Imhotep-Pedubast became High Priest of Ptah in 39 BCE but died young only nine years later.[10

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taimhotep

3 notes

·

View notes