#that whole thing of skip being a dad figure to gunnie May have started a bit contrived but i don't care i love it so much

Text

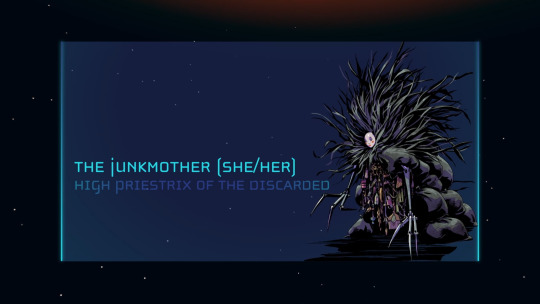

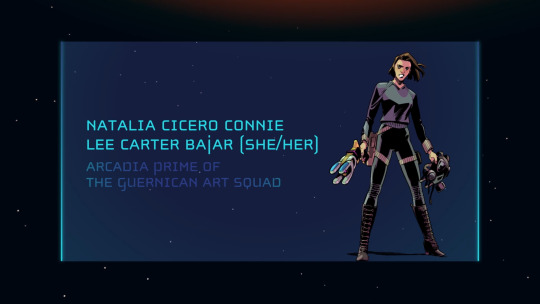

Everyone Introduced in Dimension 20′s A Starstruck Odyssey episode 11

#dimension 20 spoilers#a starstruck odyssey#dimension 20#a starstruck odyssey spoilers#GOD this ep was so funny#that whole junkmother scene on one hand was so philosophically interesting but also. it's combined with how the character LOOKS-#and murph was just head in hands the whole scene oh my God#so thrilled with the guernican art squad ordeal it felt like the Right amount of d20 insane#and also FUCK that bit of 'gunnie driving dad's car' was So great#that whole thing of skip being a dad figure to gunnie May have started a bit contrived but i don't care i love it so much#although UH. NOT looking great for skip next episode-#though that MAY be intentionally misleading on d20's part to make it Seem that way but uh#still a bit scared for him won't lie#see y'all then.#aso#aso spoilers#d20 introductions

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I was eleven years old, every girl in my class got weighed and had their height taken. The boys did too, of course, but at the time it was only the girls that I worried about. We were all put in a line. Behind the backs of our teachers, we whispered what the scale had told us.

“I’m 93 pounds.”

“Oh really? Well I’m 95. But I’m taller!”

“91 pounds.” This whisper came from the second shortest girl of our class — I was the shortest — and everyone seemed shocked.

“No WAY! You’re like, 80 pounds!”

“Nope, it’s 91. I even took off my shoes.”

“What about you, Kristina?”

I hesitated. I knew, even at that young age, that the lower the number, the better. I wrapped my arms around my suddenly-bloated stomach and smiled.

“92.” That was a lie. It was an outright, bold-faced, lie. But they believed it. I looked at my little paper, safely folded. I had already memorized what it said.

Height: 4 feet 9 inches. Weight: 100 pounds.

That’s when it clicked. The coaches had been saying this all along! To be healthy, I had to eat less and exercise more. I was not healthy if I was fat. I could not, under any circumstances, eat ice cream or cake or cookies or those Indian sweets my dad loved to bring home. Nothing with sugar, nothing that tasted good. One Hundred Pounds. I didn’t know anything else in the world that weighed One Hundred Pounds. Suddenly, I was too much. I didn’t feel qualified to play at recess or buy hot cheetos at the elementary school black market.

So that day at lunch I only ate vegetables. But then the coaches said that school lunches were healthy, so I started eating all of my lunch except for the milk. I started skipping breakfast. I didn’t even realize what I was doing. I didn’t do it consciously until that summer, when school lunches were no longer available.

The previous summer, I had lunched on ravioli or canned spaghetti or cookies and a fudge Popsicle. But that summer before middle school I discovered the wonders of the toasted peanut butter sandwich. I found — or convinced myself — that one quarter of the sandwich without crust filled me up for hours. So when we were left alone for breakfast and lunch, I usually had half a sandwich and a small serving of whatever my mother cooked for dinner.

This continued for the whole summer, and I more or less left myself alone when it came to food. At the time, I was strong. I was not fast, and I could not run for any long period of time. But I could do push-ups and the flexed arm-hang with the best of them. I realize now that it may have been the muscles, not fat, that made me 100 pounds in sixth grade.

I only put aside my eating rules around Christmas, when our house had turned into Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. It wasn’t until I was thirteen, somewhere in middle school, that I faced the scale again.

Before I continue, I must state that scales, at any given stage in my life, have been both my best friends and worst enemies. Even now, in the midst of recovery, I can’t resist stepping on the scale and praying that it’s not too high.

Anyway, I stepped on the scale that my sister had in our bathroom purely out of curiosity. I remembered my mother saying something about it being six pounds off, and stepped on. 128. Plus six? 134. I didn’t realize I was supposed to take away six, but by then it was too late. No matter what scale I stepped on, my plus-six rule would apply. One-Thirty-Four. Much too much.

My peers frowned upon anorexia. I only had about three or four friends throughout middle school, and they all thought starving yourself was stupid. So I kept it a secret. I would go to the bathroom after lunch and stick a pencil down my throat until I threw up. There were a couple of instances when I overdosed aspirin so I wouldn’t be able to eat anything without throwing up.

Overdosing became a hobby of mine. Whenever we had to go to a pizza place or have parties that required eating, but didn’t have an opportunity for me to barf, I would only slightly overdose on pills so I could get a nice little buzz in my head and be “out of it” enough to not care if I ate or not.

My parents, of course, could not know. They knew, eventually, of the running away and the cutting. They knew of the acting out and the overdoses. But they never knew why. That was my cherished little secret. It was so secret, that even I didn’t know why. I just had to do it. My behaviors were completely normal to me. Even the odder behaviors, like pretending to cast spells on people I didn't like until the 8th grade class decided to collectively follow me around singing ‘this little light of mine’.

Flash forward to high school. I was no longer the witch or the crazy girl. I was normal. At the very least, I was anonymous. I started inching back to starving myself and restricting my calories, but I did it a bit more publicly. My friends, to my surprise, were concerned about my actions rather than hostile. That year, cutting was also deemed ‘Not Cool’ because I was in theater and the Stage Rats were not allowed to alter their bodies in any way without the director’s permission.

So I stopped eating and made new friends. “John” was one of these friends, and I became very close to him. He became, and remains, a brother to me. One time, he was giving me a piggy-back ride (one of those epic ones where he would karate fight as I clung to his back) and he said “This is what I’d look like if I was 90 pounds heavier.” I looked at the shadow on the ground to see a huge, bloated figure. Somehow, I took offense.

“Great. So I’m fat?”

“What? No! I said I would look fat. Not you. I was joking.”

I laughed. “Of course… So was I, silly.”

There was another time when he pulled me into the cafeteria and sat me down in a chair. As my heart raced at the thought of food, he sat down.

“What do you want to eat?”

“I don’t have money.”

“Then I’ll pay. What do you want to eat?”

“No, it’s fine. I’m not hungry.”

“Fine, I’ll pick for you. Stay here.” I suppose I could have run out of there and hid until the bell rang. But I stayed. I trusted my adopted brother. He brought back a ham and cheese sandwich, I believe. I stared at it.

“I didn’t know what you liked, so I got you that.”

“No, it’s fine…” My voice trailed off as I calculated the calories in the sandwich.

“Kristina, what do you see in the mirror?”

“I don’t look in mirrors.”

“You know what I mean.”

“I see…” I tried to think up the biggest thing possible. “…A whale.”

He sighed. “You’re not a whale. You’re just fine the way you are.”

Regardless, I ate only half the sandwich, without the crusts. Later I joined the physical training team with my ROTC class. “Sergeant” encouraged us — especially when the military ball came around.

“Come on girls, you want to fit into your dresses, don’t you?” I did crunches until my muscles malfunctioned. I ran the mile as fast as I could until I wasn’t able to breathe and was in danger of passing out. But I loved it. I continued to exercise at home and watched my stomach getting smaller and smaller.

In October, I changed schools. The new school had an ROTC class, but not a PT team. I panicked. I started eating less, as moving left me too busy to exercise and too supervised to vomit.

Before the Big Move, I was the lead actress in a play. It was my grand exit. Through theater I learned to be assertive and I perfected my lies. I took in nothing but energy drinks and diet coke. There was the occasional celery stick or apple, but that was rare. Of course, I couldn’t get out of dinner with my parents. But late rehearsals meant no one was there to watch me only take half a serving. I drenched everything I ate in hot salsa, chili powder, or habanero sauce. The spiciness would raise my metabolism.

When the play ended and my character died, I sulked. I had become too integrated with my character, Sophia, who was older and prettier and happier than I was. When the curtains closed for the last time, Sophia died and I returned to my depressed state.

I became a workaholic. I lived on coffee, diet coke, energy drinks, and diet pills. I didn’t sleep much, preferring to work out or work on homework. Commander and Gunny (from the ROTC class) noticed it. They appreciated my intelligence, but said over and over that I should sleep. And I did. I slept in Spanish class and on the bus. To this day, I’m living in El Paso and not able to speak Spanish.

By the end of that year, I burned out. I had stress attacks, which are very much like panic attacks, only more manic/productive. I had to be better than everyone. I had to be smarter, thinner, happier, more talented, and more commanding. I had to be impressive. Extraordinary. That summer, I quit. I still took my open course psychology classes from Yale, but I wasn’t stressing over it every minute of the day. Without my work to distract me, I had more time to devote to my eating disorder, which was to be in full bloom around the start of the next school year.

In September, my father took one of his business trips. With only one parent to deal with, I stopped eating completely. I didn’t take in vegetables or fruits or metabolism boosters. I drank water and did yoga. This lasted about nine days, until my father got back home.

That night, we cooked chicken curry. Made from all raw ingredients, nothing processed, and minimal oil. It was very healthy in small portions. But I couldn’t eat it. I stayed silent throughout the cooking process and pretended to be asleep when it was done cooking.

When my sister came up to get me, I told her I wasn’t feeling well.

“Do you need anything?”

“I need my medicine.”

“Which medicine?”

“The one that makes me happy.”

I had been taking antidepressants for a while. The panic I was feeling must have shown, but my mother wouldn’t have it.

“No sympathy. You need to eat.”

“I don’t feel well!”

“Then I’ll take you to the doctor. Do you need that? I’ll call your therapist. Hmm?”

“I don’t need them.”

“Then eat.”

“No.” It was the first time I had ever stood up to my mother, ever been anything but submissive. I sat at the table with a glass of water, still crying, and sat there. My sister and father were sympathetic, but I knew there was no way I could skip out of eating the next day. But I was so proud; I had lost 12 pounds that week. Eating would ruin it all.

And it did. A week after I started eating again (apples and celery were as far as I would go); I had my first Binge Attack. I ate and ate and ate. I ate everything I could get my hands on, plus two sodas, and I ran upstairs through the empty house and stuck my fingers far down my throat until nothing but acid came out. Then I chugged water and purged again, just in case.

This is where Bulimia made its triumphant return. I stayed away from food when I could, but when I had to eat anything more than my precious cut up apples or fresh celery or diet coke, I would purge. This continued on, with the diet pills and my mother finding the diet pills and me just buying more and my sister asking if I had a “problem” and the lies, lies, lies. I had control. At least, I thought I did.

I came to school one day and everyone just stared at me. The room went silent. I was working away, having isolated myself by that point so that I was friendly with everyone, but didn’t really talk to anyone.

“Aziz,” Commander called, “You’ve lost too much weight. You need to cut the crap and eat something.” Even I was silent. I translated this into “it’s working”. You’re getting thinner. You’re on your way! I was about 108 pounds. The size of my eleven year old sister. After the silent spell, I laughed.

“Oh sure, Commander. Don’t worry; I’ve got it under control.” I was wearing my little sister’s shirt. My jeans were falling off. I had to poke new holes in my belt to keep them up. At night, if I lay down the right way, I could feel my ribs and my hip bones jutted out. I couldn’t stop feeling them. Later, when I was stressed, I would walk with my hands on my hip bones, thinking at least I’m thinner than before.

But it all went to hell the next year. I was binging and purging more often and thus, gaining more weight. I hated my body for rebelling, and I hated myself for being weak. I was back up to 120 pounds. So I collected every kind of medicine I could find and took most of it, about 100 out of 250 or so, and walked out into the desert until I fell.

I was still conscious, but I couldn’t get up. I realized what was happening. In a panic, I texted Gunny. “In desert. Need help.” I dropped my phone. I wasn’t able to work with it again, only concentrating my efforts to grabbing more pills and swallowing them, 3, 4, or five at a time. By the time I heard the search and rescue helicopter, I had become unconscious. I’ll spare you the details, but they pumped my stomach and sent me to the psych ward.

The University of Behavioral Health for Mental Disorders and Chemical Dependency - UBH, for short. I spent 29 days there, when the average was 8 to 10 days, and had fights over my potassium levels and why was I hiding food and how was I still purging and “you’re gonna die if you don’t eat something.”

“Well,” I’d quietly reply, “I know that.” In two weeks I had lost another seven pounds. I didn’t understand why they were all shocked. “That’s only half a pound a day. It’s not a lot.” They’d throw their arms up, exasperated. At the family sessions, they’d state “We’re not equipped for this. We can’t make her eat.” I repeated that over and over in my head until I only ate when I had a bunch of junk food that I could binge and purge up.

My roommate, “Laurie”, was anorexic and didn’t mind me purging. She knew me better than everyone else. When everyone was applauding me for eating, she’d sigh and say “That’s not a good thing!” Because of course I was going to purge it up.

Or when I was smiling after coming out of the bathroom or acting drunk because I was so incredibly light-headed and oh-look-I’m-flying-hello-everyone-I’m-happy-today, she would shake her head behind the backs of the doctors who thought I was improving.

On her last day, because naturally she came in after me but left before me, I made her a promise.

“I’m going to eat everything you eat for breakfast, and I’m not going to purge it.” I knew, by that time, that my body would automatically try to throw up anyway, but I meant it. We had a banana, a 90 calorie cereal box, and a donut. I made it through the banana and half the cereal before I stressed out.

“This is hard.” I laughed.

“You don’t have to eat it all. Don’t push yourself.”

I took a deep breath. The nurses, Laurie, and all the other patients were watching me.

“No,” I answered shakily, “I can do it.” I ate the rest of the cereal and half of the donut before I quit. It took everything I had to not purge it up. But that was the starting point of my recovery.

My heart was hurting, skipping, and arrhythmic. My esophagus was torn, acidic, and tired. There were nicks in my hands from purging and dirty washcloths from wiping my mouth. I couldn’t climb stairs or walk down the hall. I hated my eating disorder. So, while consciously I stayed with it, I unconsciously began eating.

I’d start with what I felt was a “binge” at lunch. The unit director had to point out that what I thought was a binge was really a portion-controlled, normal lunch. Still, I didn’t eat dinner. But it was a start.

This doesn’t mark the happily ever after. Instead, this marks the point where I worked hard and long to become normal again. Three years later, here I am. I still struggle with my disordered thoughts sometimes, but I work through them. I’m happier, healthier, more active, and I know now how precious life is. As corny as that sounds, I know I will never cut myself again or purge. The starving and binging takes a little longer. But with therapy, I can work through it.

16 notes

·

View notes