#who is pairing it with informational texts about women’s rights and the civil rights movement

Text

Crazy concept I know but maybe if you’re a bored middle aged white woman you could try not harassing your 10th graders teacher about having her class read of mice and men to the point that she’s fighting off panic attacks and losing sleep. It’s like really easy not to do that.

#y’all she gave them a MONTHS notice that they were going to be reading this book#now they’re making fucking Facebook posts about how it’s inappropriate#and how it should be banned#for things like racism sexism and foul language#and how it paints mentally ill people in a bad light#meanwhile the teacher is a biracial woman with debilitating anxiety#who is pairing it with informational texts about women’s rights and the civil rights movement#so idk maybe shut the fuck up and be more involved from the get go#rather than waiting until halfway through the book to throw a god damn fit#oops sorry i forgot god damn was one of the naughty words your evil little incel 15 year old can’t be exposed to#FUCK OFFFFFFFF

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Sex Education Pamphlet That Sparked a Landmark Censorship Case

https://sciencespies.com/history/the-sex-education-pamphlet-that-sparked-a-landmark-censorship-case/

The Sex Education Pamphlet That Sparked a Landmark Censorship Case

Mary Ware Dennett wrote The Sex Side of Life in 1915 as a teaching tool for her teenage sons.

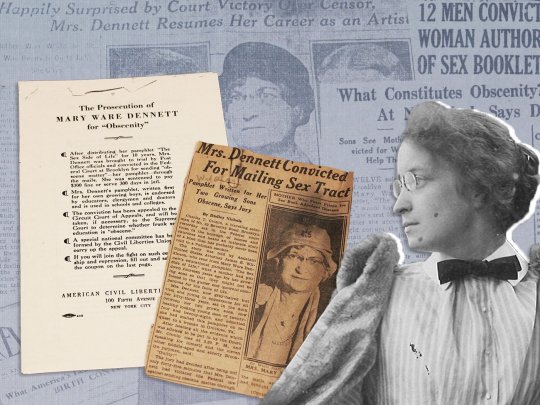

Photo illustration by Meilan Solly / Photos courtesy of Sharon Spaulding and Newspapers.com

It only took 42 minutes for an all-male jury to convict Mary Ware Dennett. Her crime? Sending a sex education pamphlet through the mail.

Charged with violating the Comstock Act of 1873—one of a series of so-called chastity laws—Dennett, a reproductive rights activist, had written and illustrated the booklet in question for her own teenage sons, as well as for parents around the country looking for a new way to teach their children about sex.

Lawyer Morris Ernst filed an appeal, setting in motion a federal court case that signaled the beginning of the end of the country’s obscenity laws. The pair’s victory marked the zenith of Dennett’s life work, building on her previous efforts to publicize and increase access to contraception and sex education. (Prior to the trial, she was best known as the more conservative rival of Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood.) Today, however, United States v. Dennett and its defendant are relatively unknown.

“One of the reasons the Dennett case hasn’t gotten the attention that it deserves is simply because it was an incremental victory, but one that took the crucial first step,” says Laura Weinrib, a constitutional historian and law scholar at Harvard University. “First steps are often overlooked. We tend to look at the culmination and miss the progression that got us there.”

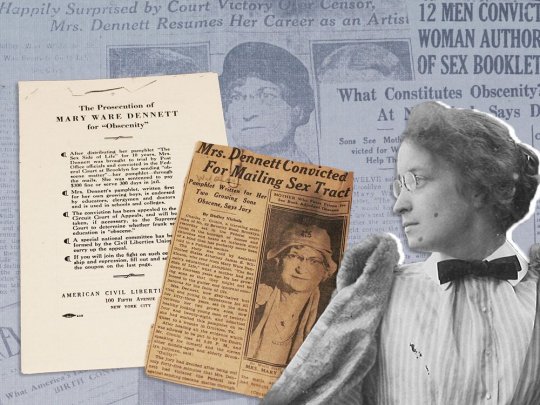

Dennett wrote the offending pamphlet (in blue) for her two sons.

Sharon Spaulding / Dennett Family Archive

Dennett wrote the pamphlet in question, The Sex Side of Life: An Explanation for Young People, in 1915. Illustrated with anatomically correct drawings, it provided factual information, offered a discussion of human physiology and celebrated sex as a natural human act.

“[G]ive them the facts,” noted Dennett in the text, “… but also give them some conception of sex life as a vivifying joy, as a vital art, as a thing to be studied and developed with reverence for its big meaning, with understanding of its far-reaching reactions, psychologically and spiritually.”

After Dennett’s 14-year-old son approved the booklet, she circulated it among friends who, in turn, shared it with others. Eventually, The Sex Side of Life landed on the desk of editor Victor Robinson, who published it in his Medical Review of Reviewsin 1918. Calling the pamphlet “a splendid contribution,” Robinson added, “We know nothing that equals Mrs. Dennett’s brochure.” Dennett, for her part, received so many requests for copies that she had the booklet reprinted and began selling it for a quarter to anyone who wrote to her asking for one.

These transactions flew in the face of the Comstock Laws, federal and local anti-obscenity legislation that equated birth control with pornography and rendered all devices and information for the prevention of conception illegal. Doctors couldn’t discuss contraception with their patients, nor could parents discuss it with their children.

Dennett as a young woman

Sharon Spaulding / Dennett Family Archive

The Sex Side of Life offered no actionable advice regarding birth control. As Dennett acknowledged in the brochure, “At present, unfortunately, it is against the law to give people information as to how to manage their sex relations so that no baby will be created.” But the Comstock Act also stated that any printed material deemed “obscene, lewd or lascivious”—labels that could be applied to the illustrated pamphlet—was “non-mailable.” First-time offenders faced up to five years in prison or a maximum fine of $5,000.

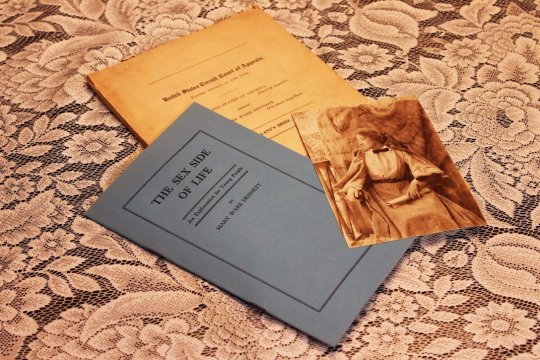

In the same year that Dennett first wrote the brochure, she co-founded the National Birth Control League (NBCL), the first organization of its kind. The group’s goal was to change obscenity laws at a state level and unshackle the subject of sex from Victorian morality and misinformation.

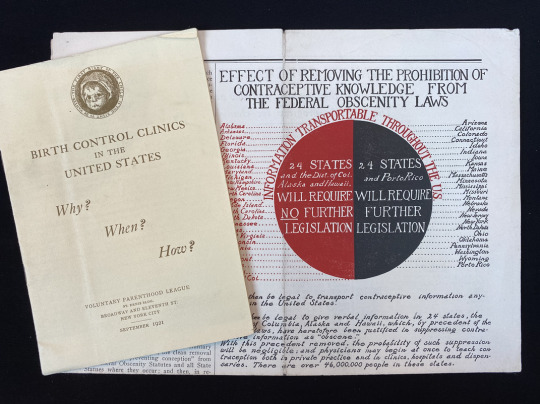

By 1919, Dennett had adopted a new approach to the fight for women’s rights. A former secretary for state and national suffrage associations, she borrowed a page from the suffrage movement, tackling the issue on the federal level rather than state-by-state. She resigned from the NBCL and founded the Voluntary Parenthood League, whose mission was to pass legislation in Congress that would remove the words “preventing conception” from federal statutes, thereby uncoupling birth control from pornography.

Dennett soon found that the topic of sex education and contraception was too controversial for elected officials. Her lobbying efforts proved unsuccessful, so in 1921, she again changed tactics. Though the Comstock Laws prohibited the dissemination of obscene materials through the mail, they granted the postmaster general the power to determine what constituted obscenity. Dennett reasoned that if the Post Office lifted its ban on birth control materials, activists would win a partial victory and be able to offer widespread access to information.

Postmaster General William Hays, who had publicly stated that the Post Office should not function as a censorship organization, emerged as a potential ally. But Hays resigned his post in January 1922 without taking action. (Ironically, Hays later established what became known as the Hays Code, a set of self-imposed restrictions on profanity, sex and morality in the motion picture industry.) Dennett had hoped that the incoming postmaster general, Hubert Work, would fulfill his predecessor’s commitments. Instead, one of Work’s first official actions was to order copies of the Comstock Laws prominently displayed in every post office across America. He then declared The Sex Side of Life “unmailable” and “indecent.”

Mary Ware Dennett, pictured in the 1940s

Dennett Family Archive

Undaunted, Dennett redoubled her lobbying efforts in Congress and began pushing to have the postal ban on her booklet removed. She wrote to Work, pressing him to identify which section was obscene, but no response ever arrived. Dennett also asked Arthur Hays, chief counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), to challenge the ban in court. In letters preserved at Radcliffe College’s Schlesinger Library, Dennett argued that her booklet provided scientific and factual information. Though sympathetic, Hays declined, believing that the ACLU couldn’t win the case.

By 1925, Dennett—discouraged, broke and in poor health—had conceded defeat regarding her legislative efforts and semi-retired. But she couldn’t let the issue go entirely. She continued to mail The Sex Side of Life to those who requested copies and, in 1926, published a book titled Birth Control Laws: Shall We Keep Them, Change Them, or Abolish Them?

Publicly, Dennett’s mission was to make information about birth control legal; privately, however, her motivation was to protect other women from the physical and emotional suffering she had endured.

The activist wed in 1900 and gave birth to three children, two of whom survived, within five years. Although the specifics of her medical condition are unknown, she likely suffered from lacerations of the uterus or fistulas, which are sometimes caused by childbirth and can be life-threatening if one becomes pregnant again.

Without access to contraceptives, Dennett faced a terrible choice: refrain from sexual intercourse or risk death if she conceived. Within two years, her husband had left her for another woman.

Dennett obtained custody of her children, but her abandonment and lack of access to birth control continued to haunt her. Eventually, these experiences led her to conclude that winning the vote was only one step on the path to equality. Women, she believed, deserved more.

In 1928, Dennett again reached out to the ACLU, this time to lawyer Ernst, who agreed to challenge the postal ban on the Sex Side of Life in court. Dennett understood the risks and possible consequences to her reputation and privacy, but she declared herself ready to “take the gamble and be game.” As she knew from press coverage of her separation and divorce, newspaper headlines and stories could be sensational, even salacious. (The story was considered scandalous because Dennett’s husband wanted to leave her to form a commune with another family.)

Dennett cofounded the National Birth Control League, the first organization of its kind in the U.S., in 1915. Three years later, she launched the Voluntary Parenthood League, which lobbied Congress to change federal obscenity laws.

Sharon Spaulding / Dennett Family Archive

“Dennett believed that anyone who needed contraception should get it without undue burden or expense, without moralizing or gatekeeping by the medical establishment,” says Stephanie Gorton, author of Citizen Reporters: S.S. McClure, Ida Tarbell and the Magazine That Rewrote America. “Though she wasn’t fond of publicity, she was willing to endure a federal obscenity trial so the next generation could have accurate sex education—and learn the facts of life without connecting them with shame or disgust.”

In January 1929, before Ernst had finalized his legal strategy, Dennett was indicted by the government. Almost overnight, the trial became national news, buoyed by The Sex Side of Life’s earlier endorsement by medical organizations, parents’ groups, colleges and churches. The case accomplished a significant piece of what Dennett had worked 15 years to achieve: Sex, censorship and reproductive rights were being debated across America.

During the trial, assistant U.S. attorney James E. Wilkinson called the Sex Side of Life “pure and simple smut.” Pointing at Dennett, he warned that she would “lead our children not only into the gutter, but below the gutter and into the sewer.”

None of Dennett’s expert witnesses were allowed to testify. The all-male jury took just 45 minutes to convict. Ernst filed an appeal.

In May, following Dennett’s conviction but prior to the appellate court’s ruling, an investigative reporter for the New York Telegram uncovered the source of the indictment. A postal inspector named C.E. Dunbar had been “ordered” to investigate a complaint about the pamphlet filed by an official with the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). Using the pseudonym Mrs. Carl Miles, Dunbar sent a decoy letter to Dennett requesting a copy of the pamphlet. Unsuspecting, Dennett mailed the copy, thereby setting in motion her indictment, arrest and trial. (Writing about the trial later, Dennett noted that the DAR official who allegedly made the complaint was never called as a witness or identified. The activist speculated, “Is she, perhaps, as mythical as Mrs. Miles?”)

Dennett’s is a name that deserves to be known.

When news of the undercover operation broke, Dennett wrote to her family that “support for the case is rolling up till it looks like a mountain range.” Leaders from the academic, religious, social and political sectors formed a national committee to raise money and awareness in support of Dennett; her name became synonymous with free speech and sex education.

In March 1930, an appellate court reversed Dennett’s conviction, setting a landmark precedent. It wasn’t the full victory Dennett had devoted much of her life to achieving, but it cracked the legal armor of censorship.

“Even though Mary Ware Dennett wasn’t a lawyer, she became an expert in obscenity law,” says constitutional historian Weinrib. “U.S. v. Dennett was influential in that it generated both public enthusiasm and money for the anti-censorship movement. It also had a tangible effect on the ACLU’s organizational policies, and it led the ACLU to enter the fight against all forms of what we call morality-based censorship.”

Ernst was back in court the following year. Citing U.S. v. Dennett, he won two lawsuits on behalf of British sex educator Marie Stopes and her previously banned books, Married Love and Contraception. Then, in 1933, Ernst expanded on arguments made in the Dennett case to encompass literature and the arts. He challenged the government’s ban on James Joyce’s Ulysses and won, in part because of the precedent set by Dennett’s case. Other important legal victories followed, each successively loosening the legal definition of obscenity. But it was only in 1970 that the Comstock Laws were fully struck down.

Ninety-two years after Dennett’s arrest, titles dealing with sex continue to top the list of the American Library Association’s most frequently challenged books. Sex education hasn’t fared much better. As of September 2021, only 18 states require sex education to be medically accurate, and only 30 states mandate sex education at all. The U.S. has one of the highestteen pregnancy rates of all developed nations.

What might Dennett think or do if she were alive today? Lauren MacIvor Thompson, a historian of early 20th-century women’s rights and public health at Kennesaw State University, takes the long view:

While it’s disheartening that we are fighting the same battles over sex and sex education today, I think that if Dennett were still alive, she’d be fighting with school boards to include medically and scientifically accurate, inclusive, and appropriate information in schools. … She’d [also] be fighting to ensure fair contraceptive and abortion access, knowing that the three pillars of education, access and necessary medical care all go hand in hand.

At the time of Dennett’s death in 1947, The Sex Side of Life had been translated into 15 languages and printed in 23 editions. Until 1964, the activist’s family continued to mail the pamphlet to anyone who requested a copy.

“As a lodestar in the history of marginalized Americans claiming bodily autonomy and exercising their right to free speech in a cultural moment hostile to both principles,” says Gorton, “Dennett’s is a name that deserves to be known.”

Activism

Censorship

Law

Sex

Sexuality

Women’s History

Women’s Rights

Women’s Suffrage

#History

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Michael Clifford goes to uni with a mountain of advice on what to expect.

None of it, it seems, turns out to actually be true.

University was supposed to be the best time of his life. Or, that’s what everybody told him, citing all the enlightening courses he would take, the raging parties he would attend, the rampant feeling of indestructible freedom he would exult in.

They failed to mention how he would be waiting in the laundry room at three in the morning because all his clothes were frankly beyond stale-smelling and starting to offend his roommates. They failed to mention that all the dryers would subsequently be filled with like, five loads of pink lacy things during his quick run to the minimart for a midnight snack to tide him over until next morning’s breakfast. They failed to mention how fucking long it takes for like, five loads of pink lacy things to actually run through a drying cycle.

Michael Clifford sits in the basement of his dormitory, a pile of dripping laundry beside him in a plastic basket with one of the handles broken, trying desperately to not fall asleep. It smells like dampness and mold and copious detergent spills.

He runs a hand through his hair and rubs along his neck, checking to see if there’s any excess dye from his escapades earlier with a bottle of purple he'd picked up on a whim last Thursday. There is, of course, and he wipes his palm along his denims.

Except he's forgotten that he's not wearing his black denims because they're all stacked up beside him. He's just wiped a streak of dark purple all down the leg of his last clean pair of pajama bottoms.

"Fuck me," he says, grumbling and rummaging among his laundry things for one of those fucking stain sticks that Calum always bugged him about getting whenever they went to the shops together. His fingers snag it but, as he's trying to extricate it from the tangle of wet, black fabrics, it slips out and rolls under one of the dryers that's still chugging along.

"Oh, fuck me."

He's so exhausted, but Michael knows from past experience that the stain will set if he doesn't treat it soon.

So, he gets down on hands and knees and just as soon as he's gotten his whole arm shoved under the dryer, fingers searching the dusty cement for the stick, and his face pressed up against the glass front of the dryer, there's clattering footsteps coming down the stairs.

"God, you fucking perv!"

What?

It takes him a second to determine that it's him that the shrieking voice is addressing, mostly due to sleep deprivation and the fact that one ear is filled with the tumbling thunder of the machine.

"What?" He didn't say he understood why he was being addressed.

Through his one available eye - the one not stuck up against the glass pane showing all the pink lacy things - he can see a flurry of long limbs flying towards him and instinctively throws himself away from the dryer.

A girl stands before him in a floppy set of sweats, arms crossed and arms furious. “You think it’s cool to drool all over a dryer with my knickers in it, huh? Think you’re smart or something, perv?”

Immediately he puts his hands up defensively. “Oh my god, oh my fucking god, no! I dropped something under the dryer and I was just trying to reach it. Jesus!”

Grumbling under her breath, she whips through the laundry room towards the row of dryers and, in one economical movement that defies the laws of physics, manages to pile all five loads of pink lacy things into a basket, and leaves in a hurricane.

+

When they told him about university, there was a lot more emphasis on the amazing things he would learn and less on the amount of time it would take for him to learn them. A lot more emphasis on renewed perspectives and a lot less on how long it would take sitting at a table in the university library reading things dead people wrote over seventy years ago to actually understand why his perspectives needed renewing in the first place.

They also neglected to mention how much of a maze the university library was and how all of the easily-accessible tables were always taken ridiculously early in the evening.

Michael Clifford sighs as he pushes himself through the gaps between the shelves, turning his body sideways so he can get back to his table as quickly as possible and still have some time to complete his coursework before today turned into tomorrow.

Of course, as he’s making the final turn at an insane angle in a narrow passage that makes it impossible to see around the other side because this is university and why would anything as simple as walking back to his table be easy for chrissakes, he bumps into another body.

Well, bumps really isn’t the right word. Crashes is more accurate. Vaguely, his mind catalogs the sensations as he begins to fall backwards from the collision: long hair whispering along the side of his neck, sharp pain in his chest from the edges of textbooks, the condensation coating the outside of a water bottle soaking into his shirt.

“Shit!” The word explodes from his mouth as he bumpers off the shelves behind him, thankfully not knocking any books off the shelves.

He’s immediately chastised by a harsh whisper.

“Will you keep it down? We’re in a library, genius.”

Snarking back automatically, Michael says, “Oh, really? I thought this was a zoo.”

“Well, it might be,” the girl on the ground replies, giving a pointed look at his hair as she readjusts her glasses.

It’s the pink lacy girl, this time dressed in an entirely different set of baggy sweats, not a speck of pink or lacy anything on her.

Fuck this, fuck his history of religion paper on transcendentalism in 19th century America. What did those dead people know anyway?

“I don’t need to put up with this shit, thanks,” he says as he picks up his books from the floor and heads out the door.

He’s going to go take a nap.

+

When they told him about the textbooks that he would have, they expressed how miraculous they would be, how every page he turned would bombard his brain with information he couldn’t live without now.

They failed to mention how much each of those pages cost. After his trip to the bookstore at the beginning of term, one would have thought that each book was bound in genuine Italian leather and illuminated in gold leaf by an isolated sect of monks who only work once every eight days and take three month-long holidays each year.

Which is why, two days later when he actually goes about writing the essay on transcendentalism in 19th century America because he really doesn’t want to flunk out of uni and have to head back to the Southern hemisphere, he’s having a mild panic attack.

His book is gone, his history text that cost him more than two weeks’ worth of wages at his part-time job, and in its place is a pro-fem book detailing the struggles of minority women after the end of the Civil Rights Movement.

It’s actually quite intriguing, and he finds himself reading through the introduction before he remembers to look in the inside cover for a name.

Michael Clifford finds what he’s looking for in blocky script written with a hunter green gel pen: Tal Harrison.

To his horror, he searches her name in the student directory and finds that she lives in his hall, on his floor. The other end of the hall, granted, which is like over fifteen doors down, but still. On his floor.

His horror mounts as another realization strikes him. If he has her book, then she must have his.

The thought of more confrontation with the pink lacy girl makes him a touch queasy. Not as queasy as shifting the majority of the food-money in his monthly budget over to paying for another copy of this book, though.

Mustering up his nerve, he takes one last look at her room number before shoving his feet into a pair of slippers and grabbing her textbook. He shuffles down the hallway, counting the doorways under his breath.

He needs to know exactly how far away from him she is so he can forevermore maintain that distance at all costs.

Stopping in thirteen doors later, Michael bites nervously at his lip before bringing his hand up to knock at the door. Three knocks, then a pause.

Which stretches out obscenely long.

He knocks again, three more times. Another pause.

Goddamn, he really needs his book back, especially considering he’s fallen into another fit of procrastination and left off the essay until tonight, even though it’s due tomorrow morning at the beginning of lecture.

Michael is just about to knock again when the door to his left opens up and a head pokes out of the frame.

“They’re never in this early, so I would suggest you stop knocking and leave. Some of us are trying to study, y’know.”

It’s the girl. The pink lacy girl. The girl that has his book.

Tal Harrison.

He starts to talk, to try and defend himself and also to ignore the fact that he failed to correctly count to fifteen, when her eyes widen, gaze dropping down to the cover of the textbook he’s still got in his hand.

“Hey,” she says, “You’re the asshole who took my book in the library! And the asshole perving in the laundry room!”

“Excuse me, I’m the asshole trying to return your book right now, thanks. And I was not perving in the laundry, Christ! I was waiting for a dryer to open up because you had filled up every single one with your shit.”

To his surprise, Tal – he figures he better start actually using her proper name now – colors, cheeks pinking up just a few shades lighter than her pink lacy things.

“Sorry,” she murmurs, ducking her head. “I…mis-prioritised. Left the wash until I ran out of everything.”

“Is that even a word?” The question is out before he can catch it, and his face flushes, realizing exactly how rude he probably sounded, especially after she had apologized.

“Nope.” She pops the p, motioning him over to her doorway. “Here, I must have your book then, right? If you have mine, we must have switched them accidentally.”

Her room is nothing like what he had expected. Although, granted, his only expectations – bare walls with a magenta punching bag in the corner – stemmed from aggressive encounters with a girl who wears loose sweats and pink lacy things.

Instead, there’s only a minimal amount of painted brick walls exposed. The rest are covered with whiteboards, which themselves flash in a rainbow of dry-erase markers detailing out complicated-looking diagrams and equations with too many foreign symbols for him to understand.

There is a neat, patterned bedspread in shades of dark blues and purples as well, along with a full bookcase and well-organized desk crammed into the rest of the space in the small single.

“Here,” Tal says, locating and extracting his history book easily from one of the stacked piles at the corner of her desk. “That’s yours, right?”

He takes it from her absentmindedly, eyes still overwhelmed by the formulas on all the whiteboards. Michael honestly thought Luke was the only one crazy enough to be into all that maths shit.

“Physics.” She plays with the pencil behind her ear and readjusts her glasses. “I’m Physics and Gender Studies. Joint degree.”

“That’s…” he starts, but she cuts him off.

“Totally weird, I know, it’s difficult to explain --”

“I was gonna say that it’s really impressive. Like, really impressive.”

She pinks again, looking pleased. “Oh. Oh, thanks. What’s yours? I’m Tal Harrison, by the way.”

Now he’s the embarrassed one. “History, just history. And I’m Michael, Michael Clifford.”

+

Someone is being killed down the hall. If there’s any way to judge by the noises, Michael would suppose that whatever the method of homicide is, it’s not a clean one.

There’s another piercing scream that cuts through the guitar solo blasted through his ears.

They didn’t mention anything about mass murder in when they told him about living at uni.

Okay, hell, they really didn’t tell him anything actually applicable to life at a university in general, so he’s just going to stop mentioning it at this point.

Five more seconds of shrieking later, and he gets up in a huff, pulling on a jumper over top his boxer shorts and puts on his slippers again. Trekking out into the hall only amplifies the noise as it bounces down the narrow passage and back up.

After some investigation, Michael finds that the sounds take him to the door to the women’s washroom.

Fuck.

One lengthy internal debate later, he tamps down the urge to walk away and turn the volume back up on his headphones. The screaming has intermingled with sobbing now, so he grits his teeth and slowly pushes the door open.

In hindsight, knocking first may have been a good idea.

The door to one of the shower stalls has become inexplicably unlocked and now sways inwards. The contents of a shower caddy are dumped across the floor, shampoo bottles and those weird poofy things that his mom keeps in their bath strewn and rolling around on the slick tile.

Tal is in there, water turned off with the world’s tiniest towel preventing him from getting an eyeful, body quivering and legs knocking.

She’s staring, petrified at the drain in the center of the shower, shallowly breathing.

He clears his throat. “Um, Tal?”

Head snapping up, her eyes widen. “Michael, thank God. Help me, um, please?”

She gestures down to the drain, motioning to the thing he previously thought was just a clump of hair in stuck in the metal grate.

“Holy hell.”

There’s a big-ass spider down there, sitting on top of the drain. He stares at the big-ass spider. The big-ass spider stares back at him and twitches its legs threateningly.

Tal shifts nervously. “Michael?”

He and the big-ass spider exchange glances once more. The eight beady eyes only serve to harden his resolve. “Okay, you’re gonna have to jump over here. I’m not getting any closer to that.”

“Jump?”

“Yeah,” he says, motioning to the little bench where the plastic shower caddy once sat. “Just, like, step up there and jump across to me and I’ll catch you. No worries.”

She wavers, indecision showing as her eyebrows furrow. “But what if I slip?”

“I’ll catch you.” He sounds much more confident than he actually is. He hasn’t worked out in a few weeks, and he’s pretty sure that chicken-boy Luke could bench more than him at this point.

But, when she does jump, she does slip. Everything slows down to half time, and he can only watch, arms outstretched to catch her, horrified as she throws her hands out to break her fall. The world’s tiniest towel drops to the ground just as she crosses the last bit of the gap between them and lunges into his chest.

Boobs. Boobs pressed against him.

Michael takes a long, hard look at the ceiling tile and contemplates his grandmother’s undergarment choices and the last time he found Calum in their room dancing suggestively around to the newest emasculating pop song.

He tries to ignore the sensation of her wet hair dripping on his collarbone as she shakes, repeating over and over, “Oh my God, oh my God, I touched it with my foot, I touched it, oh my God.”

“Tal,” he starts after she’s beginning to calm down. “Tal, um, I’m going to let go of you now and close my eyes so you can get your towel, okay.”

“Okay.”

She’s not brave enough to get anything else besides her room key and robe, and, honestly, Michael’s not either. So, they end up in his room, her in his borrowed shirt and sleep trousers – the one with the purple stripe down the leg because he didn’t end up getting to it in time after all – perched on the edge of his desk chair while he sits on his bed and makes them a cup of fortifying coffee.

They end up talking until three in the morning, even though they’ve both got early lectures the next day.

+

Okay, he lied. They did tell him one thing about uni that seems to be marginally true.

There is, often as not, a greater chance of finding really good mates at university. Some of those friendships might happen after traumatic incidents because, hey, sometimes, near-death experiences with spiders in bathrooms really bring people together.

Some of those people might be certain particular girls. Those particular girls might live on his floor.

Those particular girls might be named Tal Harrison and smell nice and are the optimum combination of really fucking smart and really fucking cute.

Michael Clifford might have a little bit of a crush.

Tal ends up routinely saving him a spot at her reserved table in the library when he wakes up late from his afternoon nap. In return, he supplies the coffee and the occasional apple that he manages to steal from Calum’s hoard of assorted fruit.

“Hey,” she says, grinning. “Make yourself at home.”

Silently, he presents the traditional offering of coffee and fruit and they settle down to their work, her on more physics coursework and him on a mountain of history readings he needed to complete by yesterday.

He can’t keep quiet for long though, as he’s distracted by the question that’s been burning on his mind for weeks. It finally bursts out.

“Why were you so mean to me when we first met?”

She twirls a piece of hair around her finger as she continues to copy down notes from her book. “Well, you were in a compromising position. You were kind of a dick. And kind of cute. So, I got flustered.”

Michael blinks. Cute?

“Also, you really did look like you were perving on my knicks so I was totally justified there.”

“You’re cute.”

Oh God, he said that out loud.

She pulls her head up to look at him for a long moment, before her eyes crinkle up in a smile. “Thanks, Mikey.”

So, when he takes her hand later as he finishes his reading and she works through the rest of her notes, it isn’t weird at all.

This is the one thing he’s going to write home about.

#5sosff#5sos fanfic#michael clifford#fic: glass in the park#updates#i'm finally posting some of my other 5sosff stuff to my tumblr!!#in case anyone is still wanting to read this

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silly Interview with Anaea Lay (who wants to read your hate mail)

Rachel Swirsky: You were in Women Destroy Science Fiction--a project I greatly admire. What appeals to you about the project? What was your story like?

Anaea Lay: The Destroy series has been so phenomenally successful and huge that it's hard to remember that it started as an announcement that basically went, "You know what? Screw this. We're going to do a thing. Details forthcoming, let us know if you're in." I'm both irritable and prone to scheming wild projects, so an announcement like that is a perfect recipe to pique my interest. I sent them my info: i actually volunteered to read their hate mail for them since I get a bit of a kick out of getting hate mail. I have a weekly quota of cackling I have to meet and reading hate mail makes it really easy for me to hit it.

They did not take me up on that offer, but did ask me to write a personal essay for a series they were putting up on their Kickstarter page. There's less cackling involved in that sort of support, but I was game. It's pretty short and you can still read it online if you want. It's mostly about how I found SF at just the right moment for it to assure me that I wasn't as alone or strange as I thought I was.

What I like most about the Destroy project as it's grown and developed is how conversations around it have grown and developed. A lot of voices that were always there, but usually at the edges or hard to go find have been amplified and brought closer to the main stream of the conversation. That's the kind of effect that stretches beyond a single anthology or project. Twenty or thirty years from now, I'll get to be the pedant droning on in convention hallways about how this and that other thing taken for granted ties back to this project and here see all the ways I can tie them together. People will humor me and act like I'm being terribly interesting, and when they finally escape, I'll cackle. (I'll probably still have a quota to meet.)

RS: You have an unpublished novel. You quote what John O'Neill had to say about it: "…an unpublished novel set in a gorgeously baroque far future where a woman who is not what she seems visits a sleepy space port… and quickly runs afoul of a subtle trap for careless spies.” Can you tell us more? How did you come up with the idea, and did it surprise you where it went?

AL: That novel was a bit of an experiment. I had a big, sprawling space opera universe that I'd been building in the back of my head for years while working on other things. It was time to start actually working on things there, but while I knew a lot about it, things in the back of my head tend to be squishy and hard to work with. So I decided to do a safety novel first, something that would let me touch on the major set pieces without any risk of pinning myself in later or breaking something I'd need.

Which meant I had no idea what I was going to do with it when I sat down. I knew I wanted a pair of sisters as the protagonists, and I wanted the younger sister to do some protecting of the older sister, then just kept throwing things out there to see what happened.

I'm in the process of re-working on of the plotlines from that novel into a game for Choice of Games. It's serving as a learning workhorse for me again because I'm using it to experiment with all the things I learned while doing my first game with them. Clearly pirates, spies, and snarky computers are the learning tools every modern writer needs in their workshop.

RS: You used to podcast poetry--how do you go about figuring how to give a poem voice?

AL: I hosted the Strange Horizons poetry podcast, but I did as little reading of the poetry as possible; that's our venue for getting in a variety of voices and it seems to me that if people are particularly invested in my voice, they can get plenty of it in the fiction podcast.

That said, I would step in when we were short on readers or there was a poem that particularly caught my eye. (Editor's privilege is a marvelous thing!) Reading poetry is both easier and harder than reading prose; poems are frequently crafted with a very deliberate ear toward how they sound, which means you're not likely to find the text dull to interpret vocally. At the same time, you then have to do justice to the choices made in how the poem was put together, and justify it being you doing the reading rather than any given reader's interior head voice. So I look for the tools the poet gave me, then look for the ways I'm best suited to using those tools and build my performance around that. I'm a complete sucker for consonant clusters and sibilants.

RS: What was wonderful about running the Strange Horizons podcast?

Running the Strange Horizons podcast is fantastic. I've given the poetry podcast over to Ciro Faienza, who was one of our staff readers for the poetry podcast and the single most common provocation of fanmail the podcast has gotten. That podcast takes a lot of work, and I'd gotten to the point where I was very aware of a lot of ways it could be better, but realistically wasn't ever going to have the time to implement any of those improvements. Ciro immediately made some great changes and I'm really looking forward to what he does as he gets into his groove.

The politic, and mostly true, answer to what's fantastic about doing the fiction podcast is getting to read the stories early and then pull them apart and put them back together in order to give a good reading. The slightly more true answer, which has been growing over the course of the podcast, is the responses I get to the podcasts from the writers and the audience. I pretty much only consume short fiction in audio form these days, which leaves me very grateful to all the places that are making it available. Every time somebody reminds me that I'm one of those people is really great, especially when they're reminding me because they liked what I did.

But also, I really like getting to pull the stories apart and put them back together.

RS: So, on your website, you claim that the rumors I am a figment of your imagination are compelling. What are those rumors and why are you compelled by them?

AL: I actually exist as a multi-bodied individual quietly working to bring the world under the rule of a mischievous alien intelligence through widespread distribution of coffee and sunlight. We've already conquered most of California and are making great headway in Washington. Every sip of coffee you take, and every day with bright, clear skies, our agenda advances that much further.

Once, upon being informed of this (it's no fun to subvert an entire civilization if they don't know it's happening - you have to advertise) the person I was warning expressed skepticism about the veracity of my claims. Apparently, according to them, the very concept of a multi-bodied individual is imaginative speculation and the idea of being one even more so.

There's not a lot I can do in the face of such claims. There are people who don't believe in the moon landing. There's not a lot I can do about people who insist on remaining skeptical about coffee and sunshine powered conspiracies. But I do find such relentless denial of obvious reality to provide a fascinating insight into human psychology, especially when the stakes are this high.

The projects question: got anything you'd like to mention to readers?

The biggest thing I'm in the middle of right now is the Dream Foundry, which is a very cool new organization that's connecting different types of creative professionals all across science fiction, fantasy, and the rest of the speculative world. We're running useful articles on our website and starting up some very fun programming on our forums. We've got really big plans for the future (Contests! Workshops! Assimilation of the entire industry into our standards for compensation and professional conduct!) but we're already doing some very neat things, which is great for an organization that's less than a year old. In the short fiction realm, I just had "For the Last Time, It's not a Raygun," come out from Diabolical Plots. It's a tiny bit a love letter from me to Seattle, though I'd understand if it looks more like hate mail to some people. Much larger, my first game with Choice of Games, "Gilded Rails," came out late last year. It's a huge (340k) interactive novel where you're trying to secure permanent control of a railroad in 1874, during the very early days of the labor movement and age of Robber Barons. You get to choose between fixing markets or helping out small scale farmers, you've got a possibly-demonic pet cat, and a supreme court ruling over inheritance law for a big tent revivalist operation accidentally turned society into a more egalitarian alternate history where just about the entire cast might, depending on what you choose, be female. Also, I snuck in hot takes about the contemporary theater and poetry scenes, which is exactly the sort of timely, incisive commentary everybody needs in their business sim. I spent roughly forever, and also an eternity, working on this, so I'm really thrilled to have it out in the world. It could be said that I'm cackling over it.

0 notes

Text

Star Trek actor shares childhood experiences in The Terror: Infamy

George Takei (center) as Yamato-San, Miki Ishikawa as Amy Yoshida, Hira Ambrosino as Fumiko Yoshida, Lee Shorten as Walt Yoshida in The Terror: Infamy (Photo by Ed Araquel/AMC)

George Takei is calling 2019 his “Summer of Internment.” As someone who was imprisoned as a child with his family in U.S.-run internment camps during World War II, his lifelong passion about educating people about this shameful chapter in American history has fresh legs, due, in part, to a pair of projects he is currently involved with. The first is The Terror: Infamy, the latest installment of the AMC horror drama anthology that is set in the same kind of camp Takei and his family were interred in. The second is They Called Us Enemy, a graphic novel that recounts Takei’s childhood experience in those American concentration camps. Interestingly enough, the Los Angeles native’s involvement with this 10-episode series came about via one of the many lectures he’s made over the past four decades about the internment of Japanese-American citizens.

“I guess it was about 20 years ago that I spoke at Occidental College, here in Los Angeles. In that class was a guy named Max Borenstein, who is now one of the executive producers at AMC. When they were brainstorming for a concept for the second edition of The Terror, he said he was a student at Occidental [back then and] he heard a speech about the internment of Japanese-Americans from George Takei. It was a horrific experience and he pitched it at the network,” the actor explained.

“That grew into this project The Terror: Infamy. Alex Woo was assigned to be the show runner for the show and he called one day to say he had an interesting project that he wanted to come over and talk to me about. When I asked him what it was about, he said it was about the internment of Japanese-Americans. I said of course—that’s my mission in life. So he came over and sat in my living room and described the project and I said this was very important.”

youtube

While this series is steeped in Japanese supernatural folklore, much of the first-hand details are shaped with Takei’s help, who supplements his role as Yamato-san, the oldest internee, as a show consultant. His advice has ranged from some of the more true-life incidents that happened at these camps including a mandatory loyalty questionnaire issued by the United States government, and the details of the living quarters to the degree of wear-and-tear that was found on the plates the imprisoned were forced to eat off of.

“Writers might define metaphor and other symbolic objects. I thought it might inspire them. When we got into filming, I was there to say this was authentic and true or that needs to be tweaked a little bit,” he explained. “The very sturdy ceramic plates that they had in the mess hall were straight from Bed, Bath & Beyond and were brand new. My memory is that of dining off of used-up, often-dropped, washed roughly, chipped-up and sometimes cracked crockery. So I was there to make these little details authentic.”

The oldest of three children, Takei was born on April 20, 1937, in Los Angeles, CA, to Japanese-American parents Fumiko Emily (née Nakamura; born in Sacramento, CA) and Takekuma Norman Takei (born in Japan’s Yamanashi Prefecture). In 1942, the Takei family was forced to live in the converted horse stables of Santa Anita Park. They were later transferred to the Rohwer War Relocation Center for internment in Rohwer, AR, before being sent back west to the Tule Lake War Relocation Center in California.

#gallery-0-5 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-5 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-5 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-5 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Takei’s graphic memoir

George Takei (Photo source: United Talent)

As a child, Takei was “…going on an adventure of discovery in the swamps of Arkansas—bayous, tadpoles that turn into frogs—it was a magical experience for me.” At the same time, he was unaware of the harrowing experience his parents were going through, thanks to FDR’s Executive Order 9066, which authorized the secretary of war to incarcerate Japanese Americans in U.S. concentration camps. The order was signed on Feb. 19, 1942 (referred to by Japanese-Americans as the “Day of Remembrance”) following the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Approximately 112,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were evicted from the West Coast of the United States and held in confinement sites across the country. While blissfully unaware of what was going on during this four-year stretch of his childhood, the willingness of Takei’s father to discuss what happened and his teenage son’s delving into American history sparked plenty of arguments and stoked the future actor’s passion about this topic.

“I had African-American friends and was involved in the Civil Rights movement inspired by speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I also read civics books and the noble ideals of democracy—All men are created equal; equal justice under the law; this is a nation ruled by law. In our case, there were no charges and no trial. The central pillar of our justice system—due process—simply disappeared,” he said. “There was outrage upon an outrage. The very fact that the American government stripped us of everything. We lost our business. Our bank account was frozen and therefore we couldn’t pay the mortgage, so the home was lost. We were stripped naked. And then they imprisoned us with no charges. We were innocent people who had nothing to do with Pearl Harbor and we were imprisoned.”

George Takei as Yamato-San in The Terror: Infamy (Photo by Ed Araquel/AMC)

His righteous indignation over these events also found him starring in the 2015 Broadway musical Allegiance, a self-described passion project based on Takei’s personal internment camp experience. Nearly five years later, he sees the same degree of xenophobia and denigration of the other rearing its ugly head again, which is why he feels The Terror: Infamy and his graphic novel, They Call Us Enemy, are so relevant today.

“I’m always shocked when I’m talking with people that I consider well informed about my childhood imprisonment and they are shocked. I’m shocked that they’re shocked and don’t know about this critical chapter of American history,” he said. “That’s why these current projects of mine are so important. We are living through a time like that right now. In my case, I was a child and we were intact as a family. The same sweeping statement that Trump has been making about the Latinos—they’re drug dealers, rapists and murderers—it’s not unlike the stereotyping of Japanese-Americans that was going on during the Second World War. We’re currently living through The Terror: The Infamy. The third season should be about the Trump Administration.”

The Terror: Infamy airs on AMC. Check local listings for times.

Season two of George Takei’s AMC series shines a light on American concentration camps. The Star Trek actor chats with Long Island Weekly's Dave Gil de Rubio about The Terror: Infamy and his childhood in an American internment camp for Japanese-American families. Star Trek actor shares childhood experiences in The Terror: Infamy George Takei is calling 2019 his “Summer of Internment.” As someone who was imprisoned as a child with his family in U.S.-run internment camps during World War II, his lifelong passion about educating people about this shameful chapter in American history has fresh legs, due, in part, to a pair of projects he is currently involved with.

0 notes