Photo

An Interview with Edna Chiang

Edna Chiang is a passionate and articulate graduate student studying microbiology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the Suen and Carey labs. Edna, an accomplished researcher who was recently awarded an NSF GRFP, also runs the Suen lab twitter. Outside of running #MooMondays and studying ground squirrel hibernation, she works with her lab to develop outreach activities about hibernation and microbiology for children.

Soleil: Could you tell me a little about how you got interested in microbiology, or science in general?

Edna: When I was really little, I wanted to be a vet or a zoologist. Sadly, one day I realized, ‘Edna, you can’t do that, you’re pretty much allergic to any warm-blooded animal that’s not a human’. So that kind of dashed my biology dreams into the dust until high school. My school offered this dual genetics and microbiology course, taught by a teacher who had gotten his Ph.D. in microbiology. I took that class, realized it was a lot of fun, and have been into microbiology ever since then.

S: Could you tell me a little bit about your thesis work and research at UW-Madison?

E: I use hibernation as a way to address various problems, including biomedical issues like diabetes, obesity, and induced comas. Hibernation is an ecological strategy that some animals use to survive the winter when it is very cold and there aren’t a lot of resources available. What I’m interested in is how mammals, specifically thirteen-lined ground squirrels, survive hibernation with the help of their gut microbes, bringing in the really complex symbiosis between microbes and their hosts. During the summer the thirteen-lined ground squirrel, which is local to Wisconsin, gorges itself on food and becomes obese. When fall rolls in and the weather gets cooler, they start hibernating, which is basically a slowing down of everything in the body including metabolism. The squirrels stop eating, stop drinking, and their body temperature drops down to about 4 degrees Celsius, the same as the temperature outside during winter. This is really crazy when you think about it, because they are doing this for about six months in a year, not eating and not drinking. How do they survive and how do their microbes help them? Once the weather warms up in the spring, they start eating and drinking again, and repeat the whole cycle. It’s this really dynamic change that happens in these animals that live right in our backyard and we have no idea how they are doing it, so the goal is to try to understand better how the microbes are helping the squirrels survive, and vice versa. It would be amazing to one day induce hibernation in non-hibernating animals, like humans. If we could get astronauts to hibernate in deep space travel, we would save a lot of energy and resources during space flight.

S: I never really thought about deep-space travel and hibernation, but that’s really cool.

E: Yeah, it’s kind of science-fictiony, but it is something we as a scientific community are definitely considering. Hibernation scientists, including my co-advisor Hannah Carey, have interacted with the European Space Agency and NASA to discuss the possibility of human hibernation.

S: When did you first get interested in using twitter to connect with other scientists and engage in science communication?

E: I really disliked Twitter; I just didn’t understand the point of it. My graduate student mentor, Marian Schmidt, whom I worked with when I was an undergraduate at the University of Michigan was the one who actually first got me interested. She really pushed me to have an online, professional presence. She got into science twitter, and I kept hearing from her ‘oh, look at this cool article I found on twitter, look at this discussion thread that’s happening on science twitter’. After hearing about all the interesting science she was finding online, I jumped into science twitter. I was surprised by how supportive and interactive it was. It’s been a very unexpectedly useful tool to have.

S: When did you take over the Suen lab twitter?

E: The Suen lab twitter began because another Suen lab graduate student, Madison Cox, took a class on social media for scientists. Part of the class was to create an online presence for your lab. She kept it active during the summer when she had more time, but she got busier during the school year and wasn’t updating it as regularly as she was during the summer. So, when I joined the lab, I was like ‘you guys have a really sad lab twitter, can I help liven it up’, and everyone said ‘go for it.’ That was one of the first things I did when I joined the lab actually.

S: Is twitter the main way that you engage in science communication?

E: Twitter is probably the way that I engage with the broadest audience, but I like to do a lot of outreach activities outside of that work as well. The Carey lab, has, and are continuing to work with the Wisconsin Institute of Discovery and the Morgridge Institute for Research to develop outreach activities relating to hibernation and microbiology. With the Carey lab, I have participated in the Wisconsin Science Festival, which is a state-wide festival that happens every fall. We are also a part of Saturday Science, which is an outreach activity which happens on the first Saturday of every month, with an overarching theme and various science exploration stations to explore different topics. My outreach, at least currently, is more catered toward younger kids.

S: Why is science communication important to you?

E: For me, it was something that was very important from the beginning. I’m a second-generation immigrant and first-generation college student. My parents moved here, and I was born and raised in the US. Because my parents didn't come from a very strong academic background, they didn’t know a lot about science, which was something I was really interested in from when I was little. One of the only ways I gained exposure to science was when my mom encouraged me to participate in a lot of after-school outreach activities. If it weren’t for all those activities, I don’t think I would have learned enough about science to want to pursue a career in it. I think most of my interest in science communication comes from the impact outreach had on me, and wanting to provide those same opportunities for children in Madison, and more broadly speaking, anyone that comes from a slightly more disadvantaged background.

You can find Edna on Twitter here

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'd like to submit a short post/bio in honor of industrial engineer Lillian Gilbreth's birthday next month (May 24th). I was wondering if there is a lag time / editorial process for submitting posts or if they are immediately published. Many thanks!

I would say give about a week, mostly because I will be out of the country traveling on the 24th and so will need to queue it up before I go and I’ll want to look it over. Thank you so much! I look forward to it.

1 note

·

View note

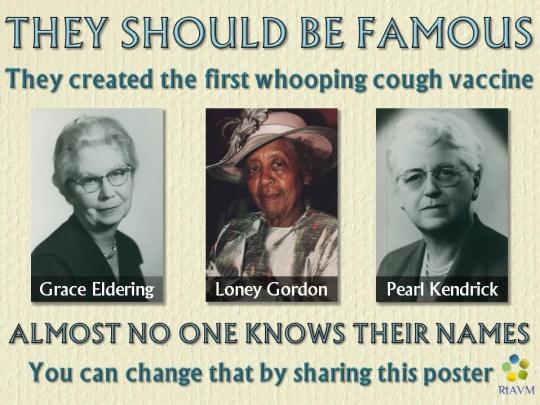

Text

Interview with Krishana Sankar of Beyond the Ivory Tower

[picture of Krishana smiling, standing in front of a window]

If you have ever scrolled through “Science Instagram,” you’ve probably come across Krishana Sankar’s Instagram account, “Beyond the Ivory Tower.” Her Instagram is (sincerely!) both fun and educational, a rare feat that Sankar pulls off with ease. Krishana is also an accomplished doctoral researcher at the University of Toronto studying diabetes, and a fierce advocate for women and marginalized individuals in STEM. She was kind enough to sit down and talk to me about her work in science communication and her research.

Soleil: When did you first get interested in science, or more generally medicine and health?

Krishana: Some people might have a specific story, or one particular incident or moment, but I don’t have one that I can remember. What I do remember, is that from an early age I enjoyed asking questions and trying to figure out how things worked. Because of that, my mom really encouraged and fostered my curiosity. She bought me science kits. One of my earliest memories was making a pH detection kit at home using cabbage juice. I enjoyed experimenting at home. I was intrigued to see how things worked for myself.

S: I know you are a grad student at the University of Toronto in the Faculty of Medicine. Could you tell me a little bit about what you study there?

K: The disease I study is diabetes. My project involves cells within the Islet of Langerhans. The Islet of Langerhans are a ball of cells within the pancreas that contain cells which secrete insulin. The aim of my project has been to figure out how to get the blood vessels in Islets to live longer once removed from a donor until ready for transplantation. I use different biological techniques, and engineering techniques, to figure out the best method to keep the blood vessel cells and beta cells (insulin producing cells in the islet) alive longer.

S: I didn’t know you could do that type of transplantation to treat diabetes.

K: Islet transplantation has been a treatment option for diabetes for quite a few years, but the procedure is not very efficient. Islet transplantation is usually performed in patients with type 1 diabetes whose blood glucose levels are difficult to control. Once the islets are transplanted into a recipient’s body, they are expected to integrate with the body. However, one of the challenges is that the blood vessels do not properly connect with the donor’s body, causing the procedure to be ineffective. The islets start to starve and die due to lack of oxygen and access to nutrients, and instead of recipients becoming independent of insulin, they begin to require their daily injections again. My project attempts to improve the efficiency of this whole transplantation process to ensure that the blood vessels in the islet are able to reconnect well with the recipient’s body.

S: Switching gears a little bit, to your Instagram “Beyond the Ivory Tower,” what inspired you to start that? Why an Instagram?

K: I was inspired to start my Instagram account as a way to deal with my burn out. I’ve been in school for what seems like forever, and I’ve never taken any breaks. It may be due to the academic culture and the way it glamorizes and glorifies constant work without breaks, and also my personality. It was a little different coming into my Ph.D. since the Ph.D. journey can be really rigorous, especially depending on environment, supervisor, and project. In my case, all of those factors were not aligning, and my project was not going as planned. I felt like my support system had started to break down, and I began burning out. One day I was on Instagram and came across some people doing science on there. I found that quite motivating and inspiring, and thought, “Why not, I have a lot to share and I’ve been through so much, I’ve got a lot of experiences.” For me, one of my greatest desires is to give back. I thought “Why not, I’ll just try this,” and I started a science account. At first, I was very unsure of how to navigate it or what my specific focus would be. I’m a very passionate person, and I tend to lead with my passion. I have not been strategic about it, so I tend to post whatever I feel like posting. And you’ll notice that’s how my Instagram is right now. It’s a mix of science, motivation, my advocacy work and inspiring women in STEM. I really started it to self-motivate and self-inspire, but I also love giving back. And to be totally honest, it has helped me. It helped me pick up the pieces [of my research] and helped me get passionate about science again. It was a really good reminder of why I do all the things I do.

S: Could you tell me a little bit about the other advocacy work you do? I know you work with Diabetes Canada.

K: I’m an advocate for diabetes, but I’m also an advocate for science literacy and promoting girls and women to remain in STEM fields. My diabetes advocacy was born out of my research. As much as I liked my bench work, I’m a very social person, and wanted more interaction with people. I also felt a great responsibility to let people know what research was happening in the lab that would hopefully go into clinical trials. I always try to find purpose in what I am doing, otherwise I don’t feel good about it. Because of that, I cofounded the Diabetes Canada University of Toronto chapter. I chatted about my idea with a colleague and within a few months, it was born. My initial role was preparing a lay presentation for the community on the types of diabetes research being done in the lab and explaining why research takes so long and so much money. We have given this presentation over 10 times and reached over 500 people affected by diabetes. It has been so successful that I was invited to participate in the national organization as an advocate and delegate. As an advocate, I visited the Ontario government on diabetes awareness day (November 14th), and spoke to different members of parliament about access to diabetes medication, and to kids with diabetes in school programs. The latter is aimed at educating teachers about what to do when they have kids with diabetes in their class and also what to do in an emergency.

I’ve been doing STEM advocacy and STEM outreach for as long as I can remember, probably since high school. Right now, I go to schools and present on the types of STEM education that are available for students. I give talks to girls especially, to dispel the stereotype of boys being better at math and engineering and to promote them getting excited and considering staying in STEM fields.

S: Do you have any other stories you want to share?

K: I have been fortunate enough not having many negative experiences being a woman in STEM. However, there is one experience I would like to share. When I joined my lab, I was the only girl. Early on, I noticed when I tried to participate in lab meetings, the men would speak over me. Initially I tried to figure out whether or not I was too soft spoken, and so I tried speaking up, however regardless of how loudly I spoke, nothing changed. I then began interrupting the men as they spoke, and I was finally being heard. Although I don’t enjoy interrupting others while they speak, I did this out of frustration. It seemed that this was the point where they realized I had something to say and began to listen when I spoke. Although, I can’t say that being ignored in the beginning was due to sexism, it was a rather frustrating experience. It led me to be more confident and assertive in what I had to say and forced me to speak louder in a room of men.

Krishana can be found on Instagram here and Twitter here.

0 notes

Photo

Today would be Dr. Saruhashi’s 98th birthday. She is remembered both as a pioneer in the study of climate change and nuclear fallout, and as a fierce advocate for women in STEM.

Spotlight on Dr. Katsuko Saruhashi

Dr. Katsuko Saruhashi was a Japanese geochemist who studied both the effects of carbon dioxide levels on seawater and the dangers of radioactive debris from nuclear testing. Her measurements of carbon dioxide levels in seawater were some of the first ever made, and she was one of the first researchers to show that the effects of radioactive fallout from nuclear bomb testing spread far from the original test site. She was also committed to supporting and promoting women in science.

Dr. Katsuko Saruhashi was born on March 22, 1920 in Tokyo, Japan. She attended Toho University (then known as the Imperial Women’s College of Science) and graduated in 1943. She was working at the Meteorological Research Institute when her friend and mentor, Yasuo Miyake, suggested she look into measuring carbon dioxide levels in seawater. At the time, few scientists were aware of or cared about global warming, and no one thought of carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas. Because of this, Dr. Saruhashi had to make much of her own equipment. She took painstaking measurements of how carbon dioxide concentration varied by location and depth. For her work, she became the first woman to be awarded a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Tokyo in 1957. One year later, she established the Society of Japanese Women Scientists to promote women in science.

In 1954, the United States conducted nuclear bomb tests at Bikini Atoll, an atoll located in the Pacific Ocean between Asia and the America’s. A crew of Japanese fishermen downwind of the test site fell ill, and one of them died, prompting Saruhashi and others at the Institute to set up monitoring stations to measure the amount of radioactivity in seawater and rainwater by Japan. She and her team were the first group in the world to look into the effects of the United States and Soviet Union’s atomic bomb tests on the world’s atmosphere. Saruhashi discovered that radioactivity from the test reached the coast of Japan a year and a half after the test. She continued her research on radiation and showed that by 1969, radiation from the tests had spread to the whole of the pacific. Her evidence was used by protesters to stop the Soviet Union and United States from performing above ground nuclear tests.

Later in her career, she showed that the Pacific Ocean releases about twice as much carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere as it absorbs, meaning it couldn’t help combat the effects of global warming.

She received numerous awards and honors throughout her career. She became the first woman to be elected to the Science Council of Japan in 1980, became executive director the Geochemistry Research Association in 1990, and became the first woman to win the Miyake prize (established by her mentor and friend Yasuo Miyake) for geochemistry in 1985. She also received many awards for her work promoting and mentoring Japanese women in science. She won the Avon Special Prize for Women in 1981 for her work on peaceful uses of nuclear power, as well as her advocacy for women scientists. She established her own prize in 1981, the Saruhashi prize, which is an annual prize given to female scientists who act as mentors and role models for younger female scientists. Saruhashi was truly a great advocate for women scientists, stating “I wanted to highlight the capabilities of women scientists. Until now, those capabilities have been secret, under the surface.” (Science, 424)

Despite her pioneering work, Saruhashi is almost never cited in western debates on climate change or the dangers of radiation testing. Saruhashi died on September 29, 2007, at the age of 87.

179 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An Interview with Marielle Pellegrino of Miss Aerospace

[caption: Marielle, smiling, in a shirt that reads Miss Aerospace]

Marielle Pellegrino is a passionate, and very smart, Smead scholar studying aerospace engineering at The University of Colorado-Boulder. Effortlessly able to describe theories from astrophysics and engineering to me (a field I have relatively little knowledge or understanding of), Marielle’s skill in explaining complicated principles comes in handy during her work at her blog, Miss Aerospace, where she explains relevant meteorological events and how to view them without fancy equipment. Despite recently returning from a conference, Marielle was kind enough to sit down and talk to me about her work in science communication and her research in aerospace engineering.

Soleil: How did you get interested in aerospace engineering and astrophysics?

Marielle: I was originally interested in astronomy and astrophysics as a child. It was my favorite thing to read about; I loved space. I was planning about doing it in the future, but my parents were influential in me looking at other options. But also, to add some context, I was serious in thinking about job offers after school as I was applying to school right during the 2008 crash. Every night on the news you would hear about kids who were not getting jobs, and I wasn’t sure if I should depend on graduate school since everyone was going to graduate school now. So I decided to pursue aerospace engineering, a more applied version of astronomy. That’s how I was led to picking it as a major. I knew I was good at physics and math, but it was never as romantic as “ahhh I want to build a rocket.” The first couple of years [of college], I kept doubting it. I always had the astronomy and astrophysics in the back of my head, so I took courses on that too in case I did apply for a Ph.D. in astrophysics. But I ended up finding something I really was interested in aerospace engineering after I took one class, astrodynamics. Its kind of funny, because the whole point of this was avoiding graduate school, and yet here I am now, a Ph.D. student, but in aerospace engineering.

S: Could you tell me a little bit about what you’re researching at the University of Colorado-Boulder?

M: My advisor is Dan Scheeres, who mainly studies small bodies, but who also does work on space debris. Small bodies specifically refer to asteroids, comets, and meteors. He brought me on because I had originally done some research on space debris for my undergraduate research, and I was really interested in astrodynamics. I particularly work on using solar radiation pressure, or solar sailing, to de-orbit debris at really high altitudes where you couldn’t use atmospheric drag, which is typically what you use at low altitudes to deorbit space debris. So I’m exploring using solar sailing and also lunar solar resonances, where the dynamics due to the sun and the moon are just right to cause chaos, which we could utilize to deorbit debris.

S: How big an issue is space debris? Are there a lot of satellites that are just inoperable orbiting still?

M: There’s actually about 20,000 pieces of traceable debris in space that’s 10 cM or larger. We know there’s probably closer to millions of objects up there. To give you an idea of how little an object needs to cause damage since they are moving at such high speeds, an object as small as 2 cM can puncture the International Space Station. So, it’s a really problematic, at low earth orbit, where most of the satellites are. To give you an idea of how bad of a situation it is a lower orbit, there’s been three major collisions there, and one of them recently was with a functioning satellite. So that was a real wake up call to the industry and why it’s becoming such an important and hot topic. I’m looking at higher orbits, where it’s not quite as big of an issue yet, but I’m looking at mitigating those problems before they actually occur.

S: I had no idea there was that much trash and debris up there

M: Yeah, when Gravity came out, it’s funny, it seems so futuristic, but it’s very much a real life concern. They [the ISS] don’t do space walks when there is a certain risk of space debris around. Satellites going up now have to have some kind of mechanism to deorbit or come back down so they aren’t clogging up space when they are done up there.

S: Is that a new trend started in recent years with the deorbiting of satellites?

M: Yeah, so there’s been the invention of something called the aerobrake, which basically increases your drag due to the atmosphere. With that, the orbit slowly degrades until it eventually burns up in the atmosphere.

S: Moving on to your work with Miss Aerospace, how did you get interested in science communications? Is Miss Aerospace the first thing you did in science communication?

M: It is definitely the first thing I did in terms of science communication. When I graduated, I had this moment of reflection. There’s so many misconceptions about aerospace engineering, and I kind of felt like a bit of an outsider my first year even though I knew I was qualified. I wanted to change that stigma for future students. And then another portion of it was that I had learned all these cool things about how to find satellites, how to watch certain meteor showers, just through my work with these different college groups, and I wanted to take that outreach to a higher level. You don’t have to be near a university to be able to experience these things, and I wanted to use the internet to be able to bring that information to a mass audience.

S: Why is science writing important to you?

M: Personally, I think everyone needs to understand why science is important. A lot of times, in conversations with my family and friends, they’ll be like “oh what you do is so over my head,” and it’s like, well not really. I think a lot of people in the industry just let it happen because it makes them look more important, but every industry has their complicated lingo, and yet they somehow manage to explain it in ways that other people can understand. I think it’s important for scientists to do the same thing so the general public can appreciate what’s going on. Science is important to the scientific community, but it needs to be important to more people not in the scientific community

S: That’s such a good point. Other people, and often it’s well-meaning, will be like, “oh you’re studying science, that’s so smart,” but science is just one field, and there are smart people in every field. It’s just this way we think of science as though it’s beyond some people, when in reality everyone is good at different things and has knowledge about different things.

M: Exactly. We need to change the talk about what it means to be a scientist.

S: Are you working on anything for Miss Aerospace right now?

M: We are in kind of a lull right now with respect to meteor showers, but NASA has some announcements in February I might cover, and at the end of this month there is a lunar eclipse that I will probably write about.

Marielle can be found on Twitter here, and at Miss Aerospace here.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An Interview With Erin Winick, of MIT Technology Review and Sci Chic

It’s difficult to pin down a single, defining word with which to describe Erin Winick, which is perhaps what makes her such a dynamic and interesting person. Touting a B.S. in mechanical engineering from the University of Florida, Winick is an associate editor at the MIT Technology Review. She is also the founder and CEO of Sci Chic, a company which sells science themed fashion and accessories, including 3D printed jewelry. In 2017, Winick was named one of the SME society’s 30 under 30. Winick has written for The Economist and Lateral Magazine, and has had a editorial featured in the New York Times. Although busy preparing for the launch of a daily newsletter through the MIT Technology Review, “Clocking In: A Daily Look at the Workplace of the Future,” Erin was kind enough to sit down and talk to me about her work in science communication and at Sci-Chic.

Soleil: Could you tell me a little about your background in science, and how you got interested in engineering? Was there any specific person or experience that excited or inspired you as a child?

Erin: As a kid, I always really liked making things, whether it was building Lego towers and science fair projects, or making art. Anything that involved making something I loved, including sewing, which was my first experience using a machine and which I think is a skill transferable to engineering. I also had a grandfather who was an engineer and really into astronomy. My family lived on the space coast, and I had another family member who worked for NASA, so I saw how cool engineering could be. I just had a family that really valued science. We’d always go out and watch rocket launches, which you can do living in Florida. I think it was a combination of all of these things that led me to engineering. In college, it really solidified that I wanted to do mechanical engineering.

S: That's actually really cool, that little anecdote about sewing. I don't think I’ve ever connected the mechanics of engineering with sewing, maybe because sewing is viewed as this feminine thing, but as you say, it really does share a lot of characteristics with other types of engineering.

E: Yeah, definitely. You use a machine and you turn something 2D into something 3D.

S: Going off of that, you seem to blend science and fashion so well. What inspired you to start Sci Chic?

E: I’ve always like sewing. I always sewed my Halloween costumes growing up, and in high school, I turned to sewing some more of my own fun projects. I never really loved going shopping or anything like that, but I would always appreciate the artistic quality of fashion. More than anything, it was my exposure to 3D printing that prompted the founding of Sci Chic. I was able to see the power of turning something you design on your computer into something that you can hold in your hand. It was kind of a natural transition into making something that I didn’t think was out there yet. The prompting was definitely my interest in 3D printing over my interest in fashion, but I’ve gotten more involved in the [fashion] community since then, and I’ve even done more sewing. I have a galaxy dress that I sewed that I like to wear, and that sort of thing.

S: How did you get interested in science-communication?

E: In high school, I was the editor-in-chief of my high school newspaper. I was really into newspaper and journalism in high school, but going into college, I knew I didn’t want to miss out on the opportunity to get a technical degree. I have a passion for being able to communicate science/STEM topics, especially engineering, to the general public. Growing up, I was really inspired by communicators like the Mythbusters, Bill Nye, and Neil Degrasse Tyson. I would go to the library and rent Bill Nye DVDs, even while we were watching them in class. In college, I saw a lot of people who really hated writing that were going into engineering. As someone who really liked it, I saw a unique opportunity to help spread the word about engineering and science. Throughout college, I had some opportunities to do freelance writing. I had four engineering internships in college, and at one of them I had a chance to work with a marketing team to publish some more technical [engineering] articles. I had a really wide range of experiences that led me to ramp up my science communication experience.

S: What exactly does your job as associate editor at the MIT Technology Review entail?

E: The specific topic area that I write on is the future of work. I pull out a lot of my engineering knowledge to write about things like automation and AI. My biggest project is helping to launch a newsletter on the future of work [since the interview, the newsletter has launched]. It’s a product that I'm completely owning, and writing for everyday on topics ranging from jobs that are set to grow this year to the new 3D printing technology that’s going to influence the manufacturing floor. In addition to writing the newsletter, I also write articles for publication on our website and in our print magazine.

S: What is it that you hope to accomplish with your science writing? Why do you think science writing is important?

E: At my current job, I’m really excited to be able to explore some of the personal stories related to the future of work, and help put big overarching statistics in perspective. Especially interesting to me are the personal impacts of manufacturing. Instead of just saying “8 million people lose their jobs due to automation,” I want to explore things like “these are the people who are going to be affected, this is how they are going to have to transition in the workforce, here's how technology might be impacting your life”. I think it's really cool to be able to tell a story about engineering through that lens, because I think engineering can seem very inaccessible. In terms of science communication in general, I love writing about science, but I’m very focused on engineering communication. I think engineering as a field has a really bad PR team. A lot of people don't know what engineers do, and what engineering is. Giving people a better idea of what engineers and scientists are doing can help create a better dialogue about science, society, and engineering. I think every person who does science communication from their own branch, whether it’s what you do as a career, or you're a scientist doing science communication, all of that helps [the conversation]. Because it’s definitely a big project trying to inform the public. it’s been a big transition from working and studying engineering to writing about it, but it’s so exciting and I’m really happy to be part of it.

S: Have you found that most people in the field of engineering communications come from engineering, or do more of them tend to have typical journalism backgrounds?

E: It’s definitely a mix. I’ve worked with people who have Ph.D.’s in the stuff they are writing about, and I’ve worked with people who come from journalism school and who have a completely journalistic education, but who have a specific interest in writing about tech. I think everyone just has to pave their own path and follow what’s best for them.

S: What are some of the difficulties that you’ve encountered, along your way to be doing this kind of writing?

E: While I was in college, I wasn’t 100% sure what I was going to do when I graduated. I really went back and forth, because while you’re in that kind of academic environment, everyone is really geared toward either research and academia or industry. This isn’t a path that anyone normally takes. I was definitely still experimenting with exactly where I was going to go, and I’m glad I had all those experiences and internships, and found my way while I was in college. A lot of the opportunities I had to do this work were ones I pursued through my networking outside of college.

Erin can be found on Twitter here and at her website here. She is also open to answering any questions about science-communication and how to get started in it, as well as questions about The Economists’ Science and Technology internship, which Erin had in 2016.

0 notes

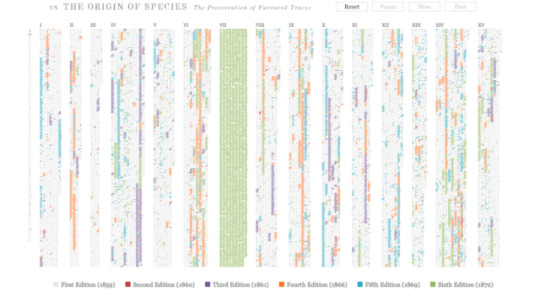

Photo

Recently, the mother of a close friend of mine told me, over grilled cheese and milkshakes, about Ben Frye’s interactive artwork “On the Origin of Species: The Preservation of Favored Traces.” Frye overlays, with color-coded highlighting, the original text of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species [1859] with the changes he made in subsequent editions. Even cooler, you can watch the changes appear, and mouse over the tiny lines of text to read them. Some of the changes are small, the edition or replacement of word, but many are longer paragraphs laying out new examples that support Darwin’s observations and thoughts, represented by long blocks of color text on the screen. The most obvious of these is the addition of a new chapter, “Chapter VII: Miscellaneous Objections to the Theory of Natural Selection” in the sixth edition (1872). While Frye’s work is a beautiful graphical representation of the evolving (hah!) nature of On the Origin of Species, it was what Abby (my friend’s mom) said to me after she told me about it that sparked my interest the most.

“You know Darwin’s wife Emma was very religious and made edits to Origin that toned down some of the language about humans? It’s interesting to wonder how much she reshaped it, and how few people know about her involvement.” Abby was right, a fact which became apparent after only a cursory Google of “Emma Darwin Origin of Spcies” (spelling has never been a strong suit of mine). According to Deborah Heiligman, author of Charles and Emma: The Darwin’s Leap of Faith (2009), Emma fixed many of Charles’ spelling and grammar mistakes, and helped him rework sentences and points to make them both stronger and more palatable to the public. To me, one of the most remarkable things about Origin, is the special care that Darwin put into making his argument one the public could follow, one that wouldn’t be too off-putting to them. And Emma likely greatly contributed to this. Despite the role she seems to have played, she is not mentioned a single time in Peter Bowler’s comprehensive treatise Evolution: The History of an Idea (2009 [1983]). Bowler, over 381 pages, tracks historical opinions and ideas about the mutability of species, as well as the historical context in which Darwin developed his theory of Natural Selection, and the myriad of sources that inspired and shaped his work. Yet Emma is not there. Perhaps it’s time historians take a page out of Heiligman’s book and start taking her role in Darwin’s writing and scholarship more seriously.

0 notes

Photo

Caption: Tera and Christine (both smiling) at the East Bay Zine Fest, Dec 2017

An Interview With Christine Liu of Two Photon Art and The Stem Squad

In the cultural imagination, science and art are opposing fields, with no overlap in techniques or practitioner. But Christine Liu, a fourth-year graduate student studying neuroscience in the Lammel lab at UC Berkeley, is proof of just how wrong this stereotype is. Using techniques like optogenetics, which allows scientists to turn “on” and “off” genetically-modified neurons and ion channels with light, she studies how nicotine addiction changes the brain, probing what neural cell populations are responsible for the positive and negative feedback loops associated with nicotine. As accomplished outside of the lab as she is in it, Liu is the co-founder, along with Tera Johnson, of the Two Photon Art collective. The two make beautiful and informative zines about scientific topics ranging from volcanoes to prosopagnosia, or face blindness. Liu also created the social media collective, which currently boasts a Facebook group and Instagram page, “The Stem Squad,” a place for women working in, and interested in, STEM to come together, support each other, and connect with others in their field. Because of her prowess in science and art, Liu was a runner-up in the Search for Hidden Figures contest. Liu was kind enough to sit down with me, and talk to me about her work with the Two Photon Art Collective and The Stem Squad (questions and answers have been edited for clarity).

Soleil: Could you tell me a little bit about your background in science, and how you got interested in neuroscience specifically? Were you always sort of drawn to the field or did you come to it after a certain experience?

Christine: I started getting really into neuroscience my senior year of high school. People were trying to figure out what college they wanted to go to, what major they wanted to pursue, and I was always good at science but I never sort of saw myself as a scientist. I was gifted a few books by friends, one of which was the Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat by Oliver Sacks, as well as The Brain That Changes Itself by Norman Doidge. Usually, even today, I’ll read about 3/4ths of a book, and I just won’t be able to bring myself to finish it. For some reason, I’ll get bored of it. But these were two books that really stuck with me, especially the idea that our brain is involved in the control of our lives, and that missing even just a small chunk of it can alter a human’s ability to go through life the same way that others do. I ended up going to University of Oregon, which has a very robust neuroscience research core, and I was able to start doing neuroscience just a few months into my freshman year and I haven’t stopped since. I feel very lucky I was able to start doing research so early in a field I love. I just kind of stumbled upon it; it was never really a mission of mine. Even going to pursue my Ph.D. wasn’t really a mission either; it just seemed like the next logical step.

S: What does science-art means to you? What are you trying to accomplish with the art you do?

C: Fundamentally, art for me is something that takes the pressure off of other aspects of my life. Its something I really enjoy doing. Even before I started Two Photons with Tera, I really enjoyed going home after a long day in lab and painting. My friend Tera, who I met doing a summer research program, and I do Two Photon Art together. It’s grown very organically based on who we are. We’re both women of color who do research and science, but didn’t always grow up being fed this (kind of) information. Science was never something I saw myself doing necessarily, which I think might be because I never had much access to this world until I became a part of it serendipitously. One of the main goals we have is to increase access to science, especially for people who don’t really identify with it. There’s this dichotomy that people often fall into that you’re either creative and artsy or you’re analytical and scientific, and oftentimes people put themselves into one box and forget to explore other sides of them. Sooner or later people forget they have that capability. So some of the work we try to do is to remind people you can be both, and you can be proud of both. We try to choose interesting topics that will reel people in who wouldn’t normally be interested, or might be intimidated by science. We make pins because of a slightly selfish motive. We were getting really active in a zine community full of artists and creative people who get to wear their passion on their sleeve. A lot of them screen print their own t-shirts, or wear enamel pins of stuff that they love. There wasn’t a lot (of enamel pins) for science, so we created them. Really, the fundamental thing is that we do the art for ourselves, but we’ve found a lot of opportunities along the way to make science a little more inclusive and welcoming to other people.

S: What was the first thing you guys created together?

C: It was the volcanoes zine, because we were in Nicaragua (together) where there are tons of volcanoes. We were hiking on volcanoes, and we were swimming in lakes with volcanic ash all over them, and we took the opportunity to be where we were and to try to disseminate the information we were learning a little more widely. We’ve grown a lot since then in terms of citing our sources, and formatting and illustration, so it’s kind of fun to look back at that one. We were just doing it for fun, and wanted to find a way to keep in touch with each other, and a driving force to hold us accountable in making art. We started it for fun, so we’ll stop doing it if it’s not fun anymore.

S: Could you tell me a little about how you started The Stem Squad, and what exactly you’ve done with it so far? How does one get involved with it?

C: So I’ll start with your last point, I would love for you to join the group. We have an Instagram page where we have the most followers, but most of the support we have occurs in the Facebook group, which has almost 800 members now. It started because I started to get more active on Instagram, with my personal account and with the Two Photon account, and I noticed that there were a handful of really expressive, honest, women in STEM who were telling the stories of their lives, and who were unafraid to embrace their femininity. I thought that was such a cool community that I really wanted to be a part of and foster connections with. We made a Facebook group, and people started inviting their own friends, and we made an Instagram page. With the Instagram page, we let people in the community take over for a week and post whatever they want about their work, their background, and it’s just grown exponentially over time. It’s really amazing. It's a very organic, pure kind of community. I don’t have to do anything to advertise it. It’s just grown from people who stumbled upon it and found that they really want to be apart of it, and there’s very little that I have to do in terms of administration to keep things caring and kind, because people in the group are so intrinsically nice and supportive and creative. I always feel weird when people give me credit for founding it, because all I did was name it and create a logo for it, but really it’s all the people inside it that do all of the work. Anyone can join, anyone who identifies as a woman, or a girl, or female in science and STEM, especially if they are interested in joining a caring community and providing resources for others as well.

S: I really like the way that you talk about it, it seems very caring, and the way you guys center care is very nice, especially since science is seen in some ways, I guess correctly, as kind of this one-man, often white, for themselves, hypercompetitive world. Community can be such an important starting point in so many things

C: Absolutely. I didn't realize how much I needed this community until I had it. It’s been really amazing seeing all the beautiful things that have come to fruition from this community. Tons of people meet up that found each other through the group. People who have started podcasts have found guests through the group, and everyone is really in there to support each other. It’s a community founded on support and collaboration, and there’s no place for competition at all. This is a place we want to be safe and free to talk about things that might be taboo to talk about elsewhere. This is just how women in STEM want to interact with each other; it’s full of love.

S: Are you working on anything in particular right now?

C: We are always working on like 3 things at a time. It’s actually pretty overwhelming because we have so many ideas, and we can’t wait to get them done, and sometimes people approach us with things we just can’t pass (up on). So one zine we are really close to being done with is a collaboration with an artist called Natelle Draws Stuff, and she does a lot of enamel pins and will donate some of the proceeds to conservation efforts. We are making a zine with her called “Same Difference”, which is about convergent and divergent evolution, and why we see so many kinds of animals that fly, but also why closely related animals have evolved different functions.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

If you want to learn more about Christine Liu and the art and science she does, check out her Twitter and her webpage. To learn more about her and Tera’s zine collective, check out Two Photon Art’s webpage and Patreon/Etsy.

4 notes

·

View notes

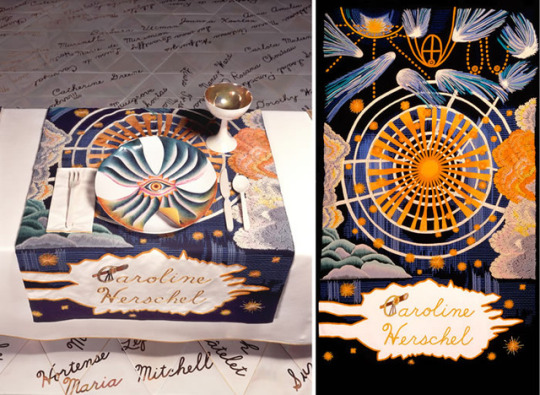

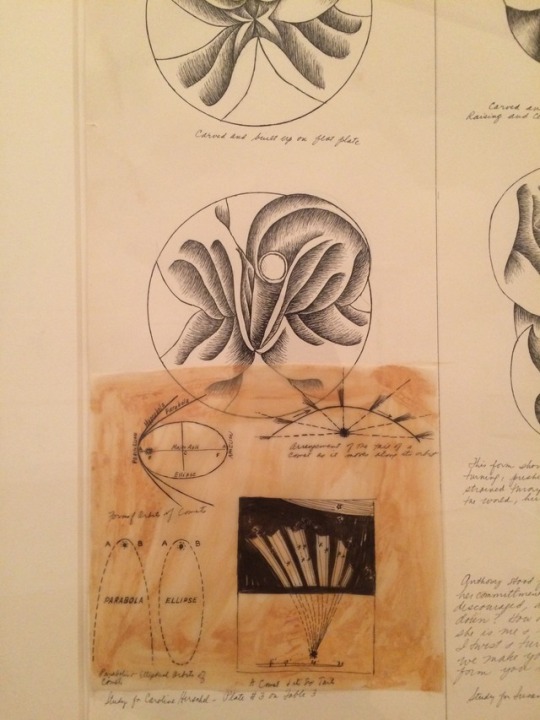

Photo

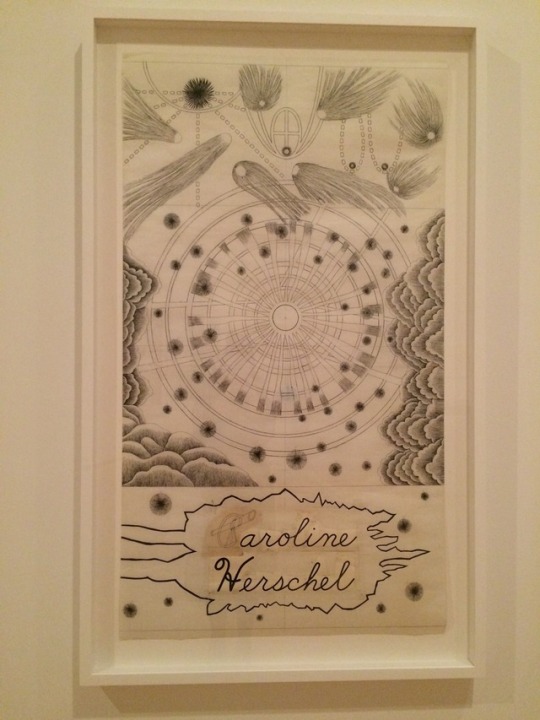

Today I went to the Brooklyn Museum, and had the pleasure of seeing Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” (1979). Frustrated with male-bias in Western art and history, Chicago conceived of The Dinner Party as a way to honor and recognize important and powerful women throughout history (although it has been critiqued, and rightly so, for mostly focusing on Western history and for representing very few WOC). There are 39 place settings at the table, one for each guest, and 999 names inscribed on the floor around the table. Each place setting features a handmade and painted ceramic plate, and a hand-stitched and personalized table runner.

I have always been especially drawn to Caroline Herschel’s place setting, pictured above. Herschel was an astronomer in the 19th century, and the first woman (that we know of) to have been paid for her scientific work, and the first woman to discover a comet! Herschel’s place at the table has a clear astronomy theme. Next to the exhibit were sketches and practice plates created by Chicago during her making of “The Dinner Party.” Two of these (the last two pictures) were Herschel’s plate. Chicago included drawings of parabolas and diagrams about planetary orbit and motion. These drawings show just how much research and care Chicago put into each individual place setting, as well as the project overall.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

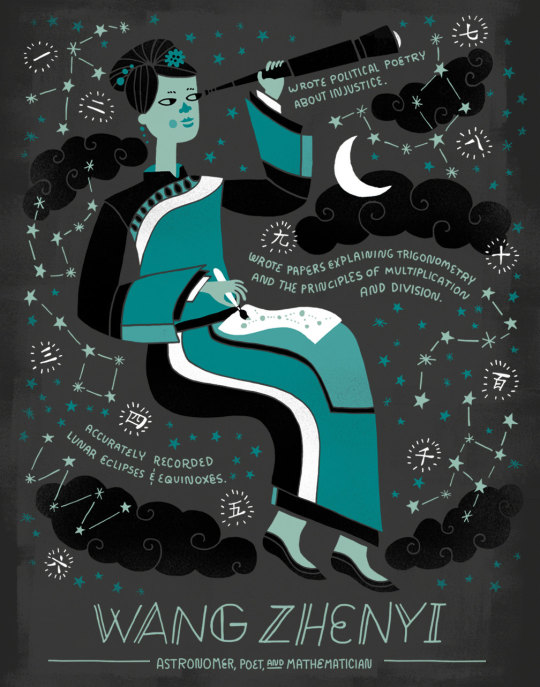

Wang Zhenyi was one of the greatest scholars in China. She was an astronomer, poet, and mathematician who accurately recorded lunar and solar eclipses and equinoxes. She also wrote political poetry about injustice.and papers explaining trigonometry and the principles of multiplication and division.

https://www.etsy.com/listing/459039646/women-in-science-wang-zhenyi

Enjoy these illustrations? Check out my new book Women in Science at

www.readwomeninscience.com

985 notes

·

View notes

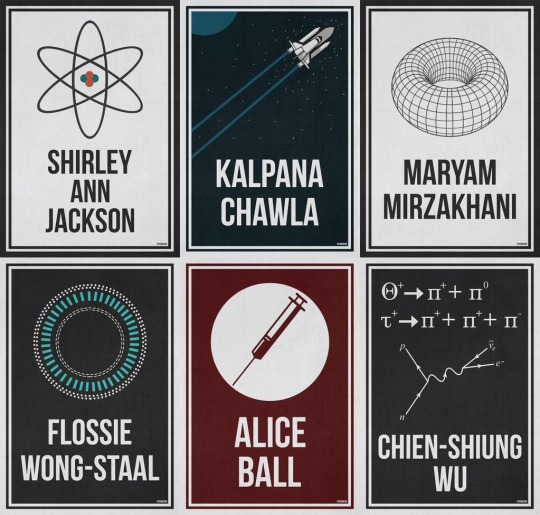

Photo

The complete ‘Women Who Changed Science - And The World" collection in honor of the 95th Women’s Equality Day.

Purchase Here!

114K notes

·

View notes

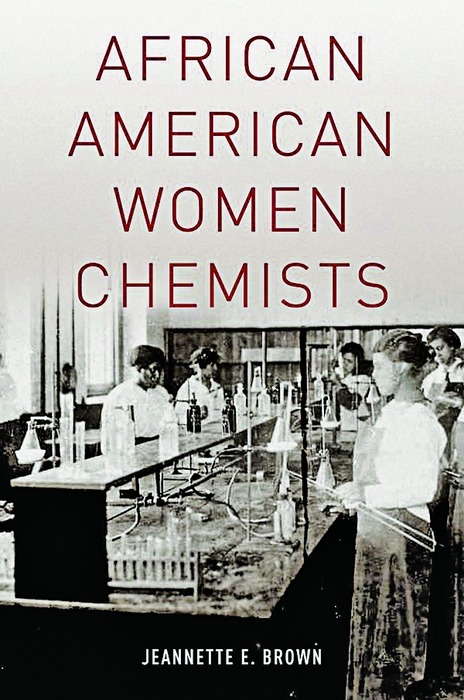

Photo

Black Women, Chemistry Pioneers

African American women staked out careers in chemistry despite racial and gender discrimination

Reviewed by Sharon L. Neal

When Chemical & Engineering News asked me to write a review of “African American Women Chemists,” by Jeannette E. Brown, I qualified my acceptance: “I am biased; I want to like it,” not only because I have a vested interest in the subject matter, but because I can’t imagine how difficult it must have been to bring this project to fruition.

It has been several years since I first met Brown—a retired Merck & Co. research chemist and the 2009 Glenn E. & Barbara Hodson Ullyot Scholar of the Chemical Heritage Foundation—and learned of her intention to write a book recounting the life stories of the first African American women chemists. Whenever I would see her at American Chemical Society meetings, she would mention this work and I would nod and smile.

Now I worry that while I tried to look encouraging, my skepticism about her ability to complete such a book poked through. I was skeptical not only because of the small number of African American women chemistry pioneers, but also because I doubted that their lives were sufficiently documented to support a book. I could name a few African American men who had earned Ph.D.s in chemistry and had careers of distinction before affirmative action—Percy Julian, Lloyd Ferguson, and Samuel Massie, for instance—but I couldn’t name any black women in chemistry from that time, distinguished or otherwise. As I smiled I was thinking, “A whole book on this topic is impossible. What source material can there be?”

The last time I saw Brown, she was clearly dealing with health challenges and using a scooter to get around at the ACS meeting. I was more convinced her book would remain unwritten. I should have known better, though. How could writing a book about African American women chemists be more impossible than the accomplishments that the book recounts? I should have realized that Brown’s determination to write the book taps the same well that helped drive her subjects to pursue success in science.

Keep reading: Chemical & Engineering News, April 2, 2012

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

(Photo provided by Prof. Padman)

Spotlight on Prof. Rachael Padman

I thought I would change up the format of this blog a little bit to take the time to highlight a woman who is currently in the STEM field. Prof. Rachael Padman is an astrophysicist who teaches at Newnham College (a woman’s only college associated with Cambridge). She was born in 1954, in Melbourne, Australia and received her Ph.D. in astronomy from St. John’s College at Cambridge. Dr. Padman has done research on stellar formation and radio astronomy, and has also openly talked about her experiences being a trans woman in STEM and academia. I was lucky enough to have the chance to email with Prof. Padman, who was kind enough to answer some questions for me.

What, if anything, drew you to astrophysics? Was there anyone or anything that encouraged you to go into science as a child?

My father was a scientist and enjoyed showing us neat things. I read a huge amount about space (mostly the solar system) while still young- most books by Patrick Moore I think.

Of all the work you have done, was there anything you were most proud of?

Probably my role in building and commissioning the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii. I led the teams building two of the first four instruments and wrote much of the data acquisition software, and all the spectral line analysis software (note: for those who don’t know, spectral line analysis looks at electromagnetic radiation given off by matter). While commissioning the telescope, a colleague, a graduate student and I found evidence that outflows (note: gas given off during the formation of a star) from young stars had to be ten to a hundred times older than generally believed, and that cleared up quite a lot of puzzles.

What kind of puzzles did it clear up?

If you can measure the velocity of the outflowing material and the distance it’s traveled (which we can), then you can deduce how long it has been going for, which we call the lifetime. This can appear to be quite short. We also have information from observations in the optical region, where velocities tend to be much higher, and distances even lower, so there the lifetimes seem very short.

Another way to get lifetimes is to look at a bunch of objects whose age you know, and see how many of them have outflows. We did that, and found that the lifetime must be much longer than you get by the first method. Going back to the physics, you can say, oh yes, a) we can’t actually see the material once it gets too far from the start (so the distances of stars must be bigger), and b) in effect the outflow material is blowing a bubble in the interstellar medium, and the bubble expands much more slowly than the material in the outflow.

What advice could you give to a young woman scientist looking to go into physics or astrophysics?

Astrophysics is a very welcoming field for a woman, at least while she is young. But it’s also a field dominated by hype (I think because of it’s wide public interest, so it generates a lot of publicity) and it’s hard to retain your integrity while playing the game well enough to advance. Choose your collaborators wisely.

Do you have any woman scientists you look up to or have looked up to?

Hmmm, hard! Not that I ever knew them, but I think Rosalind Franklin and Dorothy Hodgkin were stars, and exhibited all the right personal traits. It’s harder to find anyone that has personally inspired me, although I am pleased to count a number of women as admired colleagues.

#rachael padman#woman physicists#woman scientists#astrophysics#Astronomy#science#women in science#stem

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Teen scientist harnesses sun power to help Navajo community

New Mexico teen Raquel Redshirt uses everyday materials and the sun to build solar ovens, fulfilling a Navajo community need and winning an award at the Intel ISEF competition.

Growing up on New Mexico’s Navajo Nation, Raquel Redshirt was well aware of the needs of her community. Many of her impoverished neighbors lacked basics such as electricity, as well as stoves and ovens to cook food.

Though resources in the high desert are limited, Raquel realized one was inexhaustible: the sun. “That’s where I got the idea of building a solar oven,” the teen says.

She researched solar ovens and found that most incorporate mirrors or other expensive materials. Raquel wanted to create a design that anyone could easily afford and replicate, using readily available materials.

READ MORE HERE: http://lrinspire.com/2014/06/19/teen-scientist-harnesses-sun-power-to-help-navajo-community/

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

Spotlight on Dr. Kutlu Aslihan Yener

Dr. Kutlu Aslihan Yener is a Turkish American archaeologist who specializes in archeometallurgy and its connections to ancient trade and industry. Her discoveries and work on ancient tin mines in Anatolia (a peninsula in Turkey) proved that Anatolia as an important producer of tin (an important alloy in copper) during the Bronze Age, and indeed that trade during the Bronze Age was much more complicated and complex then previously thought. She also developed a new method of determining the chemical composition of artifacts.

Dr. Yener was born on July 21, 1946, in Istanbul Turkey, but moved with her parents to the United States when she was six months old. She was interested in science as a young child, stating she “almost lived at the Natural History Museum” (Yount, 2008). Yener originally attended Adelphi University, majoring in chemistry, but transferred to Robert College in Istanbul in 1966, where she changed her major to archaeology. She graduated in 1969, and completed her PhD at Columbia University in 1980.

Dr. Yener turned her attention to studying tin mines during her tenure as an associate professor at Bosporus University. Tin is an important metal used to make bronze, a metal that was primarily used during the Bronze Age (3000 to 1100 B.C). In 1987, Yener discovered an ancient tin mine in the mountains of Anatolia which had been used during the Bronze Age. This contradicted archeological thinking about trade in Anatolia, as silver and lead mines had been discovered, but never tin. As well, old writings suggested that the tin was imported from further east, not that it was produced in the region. In 1989, Yener also discovered the remains of a site named Goltepe near the mine. Excavations of Goltepe showed that tin smelting had occurred in it, proving that Anatolia was an important producer of tin during the Bronze Age. Yener moved to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago in 1994, where she pioneered a new technique for chemically analyzing ancient objects. Working collaboratively with Argonne Laboratory, Yener passed high energy X-rays (also known as HEX-rays, they penetrate deeper into objects and don’t cause radiation damage to them) through objects. This allows for differentiation between the different object parts and their constituent materials, as well as allowing insights into how the object was mended and made.

Dr. Yener currently works at Koç University in Istanbul and the Near Eastern Languages and Civilization department at the University of Chicago.

Sources: A-Z of Women in Science (Yount), UChicago

1 note

·

View note

Link

LEGO’s new toys celebrate women in science

Good news for lovers of tiny, plastic science - female LEGO researchers will hit shelves this August.

LEGO has announced they’ll be launching a range of female scientist figurines, along with their lab gear - and they’ll be on sale in time for Christmas.

The new set is a result of the LEGO Ideas project, which allows users to create and upload their own toy concepts. People then vote on the ideas and the winner is turned into a real product, as Geekosystem reports.

Previous winners have included a Mars Curiosity Rover and a DeLorien from Back to the Future, but we’re not sure that they’re as awesome of the winner of this Winter 2014 Review - which includes a female palaeontologist, astronomer and chemist, AND a dinosaur skeleton.

The set will be titled the LEGO Research Institute and the idea was initially submitted by Alatariel Elensar, who wrote, “The motto of these scientists is clear: explore the world and beyond!”

Here’s hoping the toys inspire a whole new generation of researchers.

love this!!!

411 notes

·

View notes