#Indo-teutonic

Text

Beautiful Asian has multiple orgasms with a pink vibrator

Natasha and Penny surprise Alex with some serious fucking

Bollyna Ganzarolli

Romantic Tinder Date Turns Into Rough Sex and Huge Facial - DarkDesires4K

Passionate real amateur sex in the kitchen and finish on the shower CUMKISS

Cute babe Susie stripping to show her perfect body

Monster cock boys cum and granny strips to cause erection for gay

Sweet teen Lily Adams

Nymphette teen naked yoga display

Blonde MILF gets her love tunnels plowed

#ethnopsychology#Indo-teutonic#africa#jockettes#galactotherapy#anti-Irish#supportingly#halibut#feeble-mindedly#regalize#staphylococcic#crabbers#Micanopy#Alderman#perityphlic#jordan#Willdon#irreality#transplantee#Evaristus

0 notes

Text

The Vikings & Norse Mythology Book Collection

The Lost Book Archive charges $15 for this collection. If you found this roundup helpful, please consider donating to the Internet Archive instead.

Mythology by Edith Hamilton (1942)

The Long Ships by Frans G. Bengtsson (1941)

(Ed note: this is a rental; I cannot find a public domain version)

The Broken Sword by Poul Anderson (1954)

The Prose Edda: Tales by Norse Mythology by Snorri Sturlusson, Jesse Byock (1220)

East o' The Sun and West o' The Moon - P. C. Asbjornsen (1921)

The Poetic Edda: Stories of the Norse Gods and Heroes (Unknown)

The Poetic Edda - H. A. Bellows (1923)

Germania by Tacitus Tacitus (AD 98)

Myths of Norsemen: Retold from the Old Norse Poems and Tales by R.L Green (1960)

(Ed note: this is a rental; I cannot find a public domain version)

Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia by E.O.G. Turville-Petre (1964)

Myths of the Norsemen from the Eddas and sagas by H. A. Guerber (1908)

The Story of Rolf and the Viking's Bow - A. French (1904)

An Elementary Grammar of the Old Norse or Icelandic language - G. Bayldon (1870)

The Road to Hel: A Study of the Conception of the Dead in Old Norse Literature (1968)

Heimskringla: The History of the Kings of Norway by Snorri Sturluson (1230)

In the Days of Giants; a Book of Norse Tales by A. F. Brown (1902)

Asgard Stories - Tales from Norse Mythology - M. H. Foster (1901)

The Children of Odin - P. Colum (1920)

Norse Mythology Or The Religion Of Our Forefathers Containing All The Myths Of The Eddas By: R. R. Anderson (1875)

The Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus Vol. 1 and 2 - S. Grammaticus (1905)

A Handbook of Norse Mythology Hardcover by Karl Andreas Mortensen (1913)

The Perfect Wagnerite - a commentary on the Niblung's Ring - B. Shaw (1912)

The Nine Worlds - Stories from Norse Mythology by M. E. Litchfield (1900)

The One-Eyed God: Odin and the (Indo-)Germanic Männerbünde by Kris Kershaw (2000)

The House of the Wolfings and all the Kindreds of the Mark - W. Morris (1888)

Bulfinch's Age of Fable or Beauties of Mythology (1855)

Asgard and the Gods by W. Wagner (1902)

Teutonic Myth And Legend - D. Mackenzie (1921)

Teutonic Mythology Vol. 1 by J. Grimm (1835)

Teutonic Mythology Vol. 2 by J. Grimm (1835)

Teutonic Mythology Vol. 3 by J. Grimm (1835)

Teutonic Mythology Vol. 4 by J. Grimm (1835)

Beowulf and The Fight at Finnsburg by F. Klaeber (1922)

Beowulf; an introduction to the study of the poem with a discussion of the stories of Offa and Finn by R. W. Chambers (1921)

The Kalevala - The epic Poem of Finland Vol. 1 and 2 - J. M. Crawford (1904)

Manual of Mythology - Greek and Roman, Norse, and old German, Hindoo and Egyptian mythology - A. S. Murray (1875)

Laxdaela Saga - translated from the Icelandic by Muriel A.C. Press (1899)

Myths of Northern Lands, narrated with special reference to literature and art by H. A. Guerber (1895)

The Heroes of Asgard - Tales from Scandinavian Mythology by A. Keary (1908)

Norse stories retold from the Eddas by H. W. Mabie (1900)

Kalevala, the land of heroes Vol. 1 & 2 - W. F. Kirby (1907)

The viking age the early history, manners, and customs of the ancestors of the English speaking nations Vol.1 by P. B. Du Chailu (1889)

The ethical world-conception of the Norse people by A. P. Fors (1904)

The Heimskringla or, Chronicle of the kings of Norway Vol. 1 - S. Laing (1844)

The Heimskringla or, Chronicle of the kings of Norway Vol. 2 - S. Laing (1844)

The Heimskringla or, Chronicle of the kings of Norway Vol. 3 - S. Laing (1844)

Viking Tales - J. Hall (1902)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

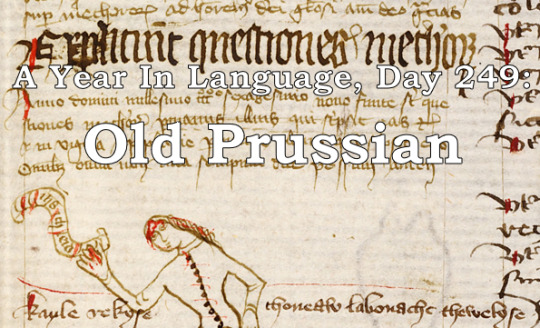

IF YOU KILL A SNAKE - THE SUN WILL CRY

Baltic culture is frequently described as extremely conservative and dedicated to tradition. This is not mere romantic and historical data. For the conservative aspects of the Baltic languages one need look no further than A. Meillet who wrote that: "Le lituanien est remarquable par quelque traits qui donnent une impression d'antiquite indo-europeenne; on y trouve encore au XVIe siecle et jusqu'aujourd'hui des formes qui recouvrent exactement des formes vediques ou homeriques..." (Meillet 1964:73). Secondly, the Baltic peoples (who at one time comprised several related tribes that are now extinct, eg. the Old Prussians) were the last Europeans to adopt Christianity. The new religion was introduced into Latvia and Prussia at the beginning of the thirteenth century by the Knights of the Teutonic Order. The Lithuanians resisted the longest and officially only joined the Christian Church in 1387 through Poland. The new faith, however, was introduced in a foreign language (Polish) and was not understood by the Baltic villagers who remained pagan.

The merger of these two religions commenced in the sixteenth century and continued for three hundred years, the Christian missionaries never entirely destroying the old religion. The final product was a syncretistic religion with only a veneer of Christianity over a surviving core of pagan belief. In this way, the Baits clearly distinguish themselves from their Slavic and Germanic neighbors who accepted Christianity at a much earlier date (the Slavs ca. tenth century, the Germans in the ninth century). As a result, these latter peoples are farther removed from their pagan past and although various folk-beliefs and customs may still exist as "remnants" of their ancient religion, their initial meaning and intent has since become quite obscured. Scholars may sometimes reconstruct plausible explanations for pagan survivals in Germanic and Slavic folk-belief, but the "folk" as such are usually quite unaware and unconcerned about them. In contrast, Baltic peasants in the early twentieth century could often explicate their own folk customs and beliefs in the same manner as their pagan ancestors did several hundred years ago.

A particularly fine example of such long-term persistence of belief from the pagan era to the present is the Balts' attitude towards the snake, a major figure of tale-type 425 M with which this study is concerned.

THE SNAKE

Chronicles, travelogues, ecclesiastical correspondence and other historical records written by foreigners often made mention of snake worship among the Old Prussians, Samogitians, Lithuanians, and Latvians. The snakes were frequently referred to as žalčiai (cognate with Žalias 'green') which has been identified as the non-poisonous Tropodonotus natrix. Sometimes the chronicles also referred to them as gyvatės, a word which is clearly associated with Lith. gyvata 'vitality' and gyvas 'living'. The following historical records should more than suffice to demonstrate that snakes were worshipped widely among the Balts.6

In the eleventh century, Adam of Bremen wrote that the Lithuanians worshipped dragons and flying serpents to whom they even offered human sacrifices (Balys 1948:66).

Aeneas Silvius recorded in 1390 an account given him by the missionary Jerome of Prague who worked among the Lithuanians in the final decade of the fourteenth century. Jerome related that

The first Lithuanians whom I visited were snake worshippers. Every male head of the family kept a snake in the corner of the house to which they would offer food and when it was lying on the hay, they would pray by it.

Jerome issued a decree that all such snakes should be killed and burnt in the public market place. Among the snakes there was one which was much larger that all the others and despite repeated efforts, they were unable to put an end to its life (Balys 1948:66; Korsakas, et al 1963:33).

Dlugosz at the end of the fifteenth century wrote that among the eastern Lithuanians there were special deities in the forms of snakes and it was believed that these snakes were penates Dii (God's messengers). He also recorded that the western Lithuanians worshipped both the gyvatės and žalčiai (Gimbutas 1958:35).

Erasmus Stella in his Antiquitates Borussicae (1518) wrote about the first Old Prussian king, Vidvutas Alanas. Erasmus related that the king was greatly concerned with religion and invited priests from the Sūduviai (another Baltic tribe), who, greatly influenced by their stupid beliefs, taught the Prussians how to worship snakes: for they are loved by the gods and are their messengers. They (the Prussians) fed them in their homes and made offerings to them as household deities (Balys 1948: II 67).

Simon Grunau in 1521 wrote that in honor of the god Patrimpas, a snake was kept in a large vessel covered with a sheaf of hay and that girls would feed it milk (Welsford 1958:421).

works: Balys 1948:66-74; Elisonas 1931:81-90; Gimbutas 1958: 32-35; Korsakas et al 1963:22-24; and Welsford 1958:420-422.

Maletius observed ca. 1550 that...

The Lithuanians and Samogitians kept snakes under their beds or in the corner of their houses where the table usually stood. They worship the snakes as if they were divine beings. At certain times they would invite the snakes to come to the table. The snakes would crawl up on the linen-covered table, taste some food, and then crawl back to their holes. When the snakes crawled away, the people with great joy would first eat from the dish which the snakes had first tasted, believing that the next year would be fortunate. On the other hand, if the snakes did not come to the table when invited or if they did not taste the food, this meant that great misfortune would befall them in the coming year (Balys 1948:67).

In 1557 Zigismund Herberstein wrote about his journey through northwestern Lithuania (Moscovica 1557, Vienna):

Even today one can find many pagan beliefs held by these people, some of whom worship fire, others — trees, and others the sun and the moon. Still others keep their gods at home and these are serpents about three feet long... They have a special time when they feed their gods. In the middle of the house they place some milk and then kneel down on benches. Then the serpents crawl out and hiss at the people engaged geese and the people pray to them with great respect. If some mishap befalls them, they blame themselves for not properly feeding their gods (Balys 1948: II 67).

Strykovsky in his 1582 chronicle on the Old Prussians related:

They have erected to the god Patrimpas a statue and they honor him by taking care of a live snake to whom they feed milk so that it would remain content (Korsakas et. al 1963:23).

A Jesuit missionary's report of 1583 reported:

.. .when we felled their sacred oaks and killed their holy snakes with which the parents and the children had lived together since the cradle, then the pagans would cry that we are defaming their deities, that their gods of the trees, caves, fields, and orchards are destroyed (Balys 1948: 11,68).

In 1604 another Jesuit missionary remarked:

The people have reached such a stage of madness that they believe that deity exists in reptiles. Therefore, they carefully safeguard them, lest someone injure the serpents kept inside their homes. Superstitiously they believe that harm would come to them should anyone show disrespect to these serpents. It sometimes happens that snakes are encountered sucking milk from cows. Some of us occasionally have tried to pull one off, but invariably the farmer would plead in vain to dissuade us... When pleading failed, the man would seize the reptile with his hands and run away to hide it (Gimbutas 1958:33).

In his De Dies Samagitarum of 1615, Johan Lasicci wrote:

Also, just like some household deities, they feed black-colored reptiles which they call gioutos. When these snakes crawl out from the corners of the house and slither up to the food, everyone observes them with fear and respect. If some mishap befalls anyone who worship such reptiles, they explain that they did not treat them properly (Lasickis 1969:25).

Andrius Cellarius in his Descripto Regni Polonicae (1659) observed:

although the Samogitians were christianized in 1386, to this very day they are not free from their paganism, for even now they keep tamed snakes in their houses and show great respect for them, calling them Givoites (Balys 1948: II 70).

T. Arnkiel wrote that ca. 1675 while traveling in Latvia he saw an enormous number of snakes.

die night allein auf dem Felde und im Walde, sondern auch in den Häusern, ja gar in den Betten sich eingefunden, so ich mannigmahl mit Schrecken angesehen. Diese Schlangen thun selten Schaden, wie denn auch niemand unter den Bauern ihren Schaden zufügen wird. Scheint, dass bey denselben die alte Abgötterey noch nicht gäntzlich verloschen (Biezais 1955: 33).

The Balts' positive attitude towards the snake has been recorded also in the late nineteenth century in the Deliciae Prussicae (1871) of Matthaus Pratorius who observed: "Die Begegnung einer Schlange ist den Zamatien und preussischen Littauern noch jetziger Zeit ein gutes Omen (Elisonas 1931:8.3).

Aside from the widespread attestation of snake-worship among the Baits and its persistence into Christian times, these historical records also suggest an intriguing relationship between Baltic mythology and our folk tale. Both Simon Grunau (1521) and Strykovsky (1582) mention the worship of the snake in close reference to the god Patrimpas. This deity is commonly identified as the "God of Waters" and his name is cognate with Old Prussian trumpa 'river'. The close association between the snake and the "God of Waters" has prompted E. Welsford to suggest a slight possibility that the water deity Patrimpas was at one time worshipped in the form of a snake (Welsford 1958:421). A serpent divinity associated with the water finds numerous parallels among Indo-European peoples, eg. the Indie Vrtra who withholds the waters and his benevolent counterpart, the Ahibudhnya 'the serpent of the deep'; the Midgard serpent of Norse mythology; Poseidon's serpents who are sent out of the sea to slay Lacoon, etc. A detailed comparison of the IE water-snake figure would far exceed the limits of this paper, nevertheless, it is curious to note that except for the quite minor Ahibudhnya, most IE mythologies present the water-serpent as malevolent creature — an attitude quite at variance with that of the ancient Balts.

From the historical records it is difficult to determine to what extent the ancient Balts might actually have possessed an organized snake-cult. Erasmus Stella's account of 1518 concerning the Sudovian Priest's introduction of snake-worship into Prussia might suggest such an established cult. In any event, that the snake was worshipped widely on a domestic level cannot be denied. In general it was deemed fortunate to come across a žaltys, and encountering a snake prophesied either marriage or birth. The žaltys was always said to bring happiness and prosperity, ensuring the fertility of the soil and the increase of the family. Up until the twentieth century, in many parts of Lithuania, farm women would leave milk in shallow pans in their yards for the žalčiai. This, they explained, helped to ensure the well-being of the family.

In 1924 H. Bertuleit wrote that the Samogitian peasants "even at the present time, staunchly maintain that the žaltys/gyvatė is a health and strength giving being" (Balys 1948: II 73). To this day in Lithuania, the gabled roofs are occasionally topped with serpent-shaped carvings in order to protect the household from evil powers.

The best proof of the still persistent respect, if no longer veneration, of the snake (or žaltys in specific) is provided by various folk sayings and beliefs which were recorded during this century. Some of them clearly reflect the association of the snake with good luck, while others depict the evil consequences which will befall one if he does not respect the snake. The following are some examples:7

Good luck

1. If a snake crosses over your path you will have good luck.

2. If a snake runs across your path, there will be good fortune.

3. Žaltys is a good guardian of the home, he protects the home from thunder, sickness and murder.

4. If a žaltys appears in the living room, someone in that house will soon get married.

Bad consequences

5. In some houses there live domestic snakes; one must never kill this house-snake, for if you do, misfortunes and bad luck will fall on you and will last for seven years.

6. If you burn a snake in a fire and look at it when it is burning, you will become blind.

7. If you find a snake and throw it on an ant hill, it will stick out its little legs which will cause you to go blind.

8. If s snake bites someone and the person then kills the snake, he will never get well.

9. If a snake bites a man and another person kills it, the man will never recover.

10. If you kill the snake that bit you, you will never recover.

11. If a žaltys comes when one is eating, one must give it food, otherwise one will choke.

12. When children are eating and a žaltys crawls up to them, he must be fed; otherwise the children will choke.

13. If you kill a žaltys, your own animals will never obey you.

14. If someone kills a snake, it will not die until the sun has set.

15. If you kill a snake, the sun cries.

16. If you kill a snake and leave it unburied, the sun grows sick.

17. When a snake or a žaltys is killed, the sun cries while the Devil laughs.

18. If you kill a snake and leave it in the forest, then the sun grows dim for two or three days.

19. If you kill a snake and leave it unburied, then the sun will cry when it sees such a horrible thing.

20. If you kill a snake, you must bury it, otherwise the sun will cry when it sees the dead snake.

The snake's name.

21. If one finds a snake in the forest and wants to show it to others, he must say: "Come, here I found a paukštyte (little bird)!", otherwise, if you call it a gyvate, the snake will understand its name and run away.

22. If you see a snake, call it a little bird; then it will not attack humans.

23. While eating, never talk about a snake or you will meet it when going through the forest.

24. Snakes never bite those who do not mention their name in vain, especially while eating and on the days of the Blessed Mary (Wednesdays and Sundays).

25. On seeing a snake you should say: "Pretty little swallow." It likes this name and does not get angry nor bite.

26. If someone guesses the names of a snake's children, the snake and its children will die.

27. If you do not want a snake to bite you when you are walking though the forest, then don't mention its name.

28. A snake does not run away from -those who know its name.

29. Whoever knows the name of the king of the snakes will never be bitten by them.

30. One must never directly address a snake as gyvatė (snake); instead, one should use ilgoji (the long one) or margoji (the dappled one).

Snakes and cows.

31. Every cow has her own žaltys and when the žaltys becomes lost, she gives less milk. When buying a cow, a žaltys should also be bought together.

32. If you kill a žaltys, things will go bad because other žalčiai will suck all the milk from the cows.

Life-index and affinity to man

33. Some people keep a žaltys in the corner of their house and say: if I didn't have that žaltys, I would die.

34. If a person takes a žaltys out of the house — that person will also have to leave home.

35. If a žaltys leaves the house, someone in that household will die.

Enticement.

36. When you see a snake crawl into a tree trunk, cross two branches and carry them around the tree stump. Then place the crossed branches on the hole through which the snake crawled in. When the sun rises, you will find the snake lying on these branches.

37. When you see a snake and it crawls into a tree-stump, take a stick and draw a circle around the stump. Then, break the stick and place it in the shape of a cross and the snake will crawl out and lie down on the cross.

Miscellaneous.

38. If a snake bites you, pick it up in your hands and rub its head against the wound. Then you will get well.

39. When one is bitten by a snake, say: "Iron one! Cold-tailed one! Forgive (name of person bitten)," while blowing in the direction of the sick person.

40. If you throw a dead snake into water, it will come back to life.

41. A snake attacks a man only when it sees his shadow.

42. They say that when a snake is killed, it comes back to life on the ninth day.

43. If a snake bites an ash tree, the tree bursts into leaf.8

44. If someone understands the language of the snakes, whey will obey him and he can command them to go from one place to another.

45. If there are too many snakes and you want them to leave, light a holy fire at the edge of your field and in the center; all the snakes will then crawl in groups through the fire and go away, but you must not touch them.

Some folk-beliefs show an obvious Christian influence and are possibly the products of frustrated Jesuit anti-snake propagandists:

45. When you meet a snake you must certainly have to kill it for if you fail to do so, then you will have committed a great sin.

46. If you kill a snake, you will win many indulgences.

47. If you kill seven snakes, all your sins will be forgiven.

48. If you kill seven snakes, you will win the Kingdom of Heaven

Such examples as these, however, are quite rare in comparison to the folk-beliefs which are sympathetic to the snake.

Considering the evidence amassed from both historical records and folk-belief that the Balts possessed a positive and reverent attitude towards the snake, it is little wonder that the snake husband's death is viewed as tragedy. If, as the proverbs suggest, a snake's death can affect the sun, then what consequences might the death of the very King of the Snakes have among mortals? This tragic outcome, as Swahn has indicated, gives the tale a character which is foreign to the true folk-tale (Swahn 1955:341). This tale could not terminate on the usual euphoric note typical of the Märchen (although the tale does contain numerous Märchen motifs) because the main event of the story relates to a "reality" which the people who tell the story still hold to be true. The tale is thus well-nourished in a setting where such folk-beliefs about the snake persist. On the other hand, the tale itself may have played a part in affecting the longevity of the beliefs. Whichever case may be true, it is obvious that both are closely related.

A specific element of folk-belief that survived as an ideological support to the tale is that of the snake's name-taboo. The tragic killing of the snake king is implemented only because the name formula is revealed. Thus, the general snake-taboo proverbs (No. 21-30; receive a specific denouement in the snake-father ordering that his name and summoning formula not be revealed to others. There appear to be two important aspects that surround this name-taboo. First of all, it reflects the primitive concept of one being able to manipulate another when his name is known. A second aspect is that the name-taboo may rest on the reverence and fear of a more powerful supernatural being that requires mortals never to mention the deity's real name. For example, Perkūnas, the all-powerful Thunder God of the Balts, has many substitutes for his real name which are usually onomatopoeic with the sound of thunder, eg. Dudulis, Dundulis, Tarškulis, Trenktinis. In our tale the general reason for the name-taboo may be partially related to this second explanation especially since there are a number of variants for the name of the snake-king, eg. Žilvine, which have no etymological support but bear a suspicious resemblance to the word žaltys 'snake'. This might then indicate a deliberate attempt to destroy the name žaltys in such a way as to avoid breaking the name-taboo but still retain some of the underlying semantic force. On the other hand, it must be admitted that many of the summoning formulas include a direct reference to the husband as žaltys. In these cases, since the brothers know his name, they can extend their power over him. It is likely that both these aspects should be considered when explaining the name-taboo of the story. The clear distinction between the obviously Christian folk-sayings (No. 45-48) and the underlying pro-snake proverbs carries considerable significance when one views the substitution of the Devil for the snake in many of the Latvian variants. This substitution occurred in all probability with the increasing influence of Christianity and its usual association of the serpent with the Devil as in the Garden of Eden story. It is interesting to reflect that in some cases the entire story proceeds with the same tragic development despite this substitution (Lat. 2, 7, 9, 15). Even in the Lithuanian variant (Lith. 4) where an old woman tells the heroine that her snake-husband is actually the Devil, this does little to alter the tragic tone of the tale's ending. Thus, it would seem that the Devil is a relatively late introduction, sometimes amounting to little more than a Christian gloss of the snake's real identity. On this basis, one might well conelude that the tale must have been composed in pagan times and is thereby, at the very least, four or five centuries old if not far older.

The effect of the diabolization of the snake among the Latvian variants seems to have led to a disintegration of the tale's actual structure. In some of the Latvian redactions (Lat. 4, 8, 15) where the Devil is the abductor, the story simply ends with the killing of the supernatural husband and the heroine's rescue. In variants of the tale which progress with such a rescue-motif development, it is important to observe that many of the other elements are consequently dropped. There is no name-taboo or magic formula, sometimes no children, and, of course, no magical transformation. Thus the tale is stripped of all these other embellishments and appears rather bare. It simply relates an abduction of the heroine and her rescue, usually accomplished by some members of her family or a priest and thunder storm (Latv. 15). In any event, the abductor is one whom she quite definitely cannot marry and therefore, there can be no Märchen marriage-feast. When the tale has been altered, the rescue motif can then be correlated to the other Märchen tale-types where the heroine is abducted (rather than married) and is eventually rescued by an eligible marriage partner. One might even speculate that this will be the eventual fate of those particular Latvian variants which no longer specify that the snake, a sacred and positive being, is the supernatural husband. We then have an intimate relationship between folk-belief and folk-tale which ultimately may be mirrored in the very structure of the story.

The place of the snake in Baltic folk-belief and its relation to our tale now having been well established, the obvious next question is whether similar beliefs exist in the neighboring non-Baltic countries and, if not, might we propose this as a possible explanation why the story as a Baltic oicotype has not spread to these other cultures. A complete analysis of the role of the snake in Germanic and Slavic folk-belief would far exceed the time allotted for the composition of this study, nevertheless, some of the evidence arrived at by way of a cursory review should be brought forth.

Of sole interest in our investigation of snake beliefs among the Germans and Slavs is the extent to which these cultures parallel the Balts with respect to the lat-ter's quite sympathetic attitude toward the snake. Bolte and Polivka, Hoffmann - Krayer and J. Grimm all mention that among the Germans there are some beliefs which view the snake in a positive light. A few specific entries in Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens are similar to some folk-beliefs already cited among the Balts (Hoffmann - Krayer 1935-36: VII 1139-1141). Bolte and Polivka in listing parallels to Grimm's Märchen von der Unke cite several instances of snakes bringing great fortune to those who treat them well and disaster to those who disrespect or abuse them (Bolte and Polivka 1915: II 459-465) .9 Both Hoffmann-Krayer and Grimm, after listing various "remnants" of what they maintain might be evidence for an ancient snake-cult in Germany, state that under the influence of Christianity the snake is usually diabolized and its image as a malignant and deceitful creature predominates. Only in some very "old" stories are there traces of the original heathen positive attitude towards the snake (Grimm 1966: II 684); Hoffmann - Krayer 1935-36: VII Sp. 1139).

Welsford, in writings about the snake-cult among the ancient Slavs, states that it was probably quite similar to the one which persisted among the Baits, but that the latter seems to have retained it much longer. In the Slavic countries the snake was usually regarded as a creature in which dead souls were embodied and through time came to be viewed mostly as a dangerous animal. It is this aspect of the snake which appears most often in Slavic stories. The snake seems to be similar or even identical with other evil antagonists such as Baba Yaga (Welsford 1958: 422). There are also many stories involving a hero or heroine who has been transformed into a snake by evil enchantment.10 These stories primarily relate how this "curse" is ultimately overcome.

These remarks indicate that the respect for the snake and its association with good fortune was also known to both Germans and Slavs. The heathen past, however, is farther removed from these peoples than form the Latvians and Lithuanians. If similar snake-cults existed in Germany and in Slavic lands, they were not practiced on the same scale within recorded history as they were by the Baits. The cited fourteenth to eighteenth century reports on the Baits were written by Slavs and Germans and already then the surprise and disgust with which they viewed Baltic snake-veneration gives us a good indication of the place of the snake within their own cultures.

Cursory perusal of present-day Germanic and Slavic beliefs about the snake seems to verify the fact that, indeed, the snake is usually considered deceitful and malevolent. The majority of folk-beliefs, expressions, and proverbs reflect this general negative attitude. There are only a few examples of a positive regard for the snake, usually associating it with powers of healing. One may speculate that the folk medicine beliefs which prescribe the use of a snake as an effective cure may be partially explained by the notion that evil conquers evil (ie. an extension of similia similibus curantor). This, however, is mere speculation for it is also likely that the snake's obvious vitality may be responsible for its specification in various folk cures. This latter case seems to be well supported in the Baltic beliefs (cf. folk-belief 38, 39) since the name for snake, gyvatė, and its association with gyvata 'life' helps one to consciously sense the logical correlation.

Stories which mention the affinity between snakes and children are probably known throughout the world because they describe an unexpected occurrence. W. Hand has suggested that the credibility of such stories rests on the notion that the child's innocence and helplessness can not be breached even by a snake (Hand 1968). Note that this kind of logic presupposes that the snake is evil.

Hence, although a more thorough investigation is definitely required, one may still suggest that the Baits have sustained through their history a more sympathetic regard for the snake than either the Germans or Slavs. Assuming that this hypothesis may be true, let us now see how it might be related to the discussion of our tale.

When one assumes no comparable folkloric basis among the Germans and Slavs with regard to the snake, then the Baltic tale would make very little "cultural sense" to these people and even if it penetrated into their cultural spheres, it would probably by altered by the same process which seems to be occurring with the Latvian tales. Secondly, even if we posit the existence of a similar positive attitude toward the snake in these cultures at a pre-Christian time, these beliefs would now seem to have almost entirely died out. In any case, even though there may be some survivals, there has been no comparative retention of respect and reverence for the snake among the Germans and Slavs as one finds with the Baits. The narrative motif of this tale clearly rests on a folk-belief which serves as an ideological backbone to the story. Conversely, people unfamiliar with the underlying folk-belief or possessing quite antithetical beliefs would find this tale lacking in cultural meaning and, therefore, "untransferable," at least in its original form.

TREES

Another typical element of the Baltic 425 M tale is the terminating motif where the heroine and her children are transformed into trees. Swahn has commented that it is this motif which gives the tale the character of an aition-legend (Swahn 1955: 341). However, most Baltic aetiological-legends rarely possess such fantastic Märchen-type motifs as a supernatural husband, difficult tasks or name taboo and are certainly not so elaborate or complex as this specific tale. The explanation for the curse-inflicted transformation is based in Baltic folk-beliefs. First of all, the power of the heroine's word is what brings about the arboreal transformation. To this very day the Balts believe that a parent's curse is most effective in bringing about dire consequences to her children. This belief is, of course, also well known in other cultures. Secondly, one can observe that the transformation into trees is typically Baltic. The full impact of this motif to the Baits is directly related to their folk-beliefs and is not simply an element of the story to be appreciated on an aesthetic basis. The Balts have retained to this very day a special empathy for trees. They believe that trees are like humans in that they also have a heart and blood (sap). When cut down without good reason, they feel pain and there are folk accounts of how real blood has flowed out of injured trees. For this reason, parents always instruct their children (as this writer was instructed) never to pluck leaves, break the branches or peel the bark from a tree since it experiences the same kind of pain as when someone pulls the hair of one's head or peels off his skin from his body. Whoever injures a tree in such a manner will eventually have to suffer a similar pain in his own life. Trees also have a language of their own which man is unable to understand. One can, however, hear a tree cry and moan every time an axe digs into its trunk by putting his ear to the tree-trunk.

All these current beliefs stem from a conviction rooted in the pagan era that the souls of the dead actually go into trees, usually the ones growing near a person's homestead or more specifically, near his grave. For this reason, trees in cemeteries are considered especially sacred and must never be touched by a pruner's hand since "to cut a cemetery tree is to do evil to the deceased" (Gimbutas 1963: 191). This belief in total reincarnation of one's life force in a tree has been slightly altered by the influence of Christianity. It is quite commonly heard that souls which must undergo penance for their sins are sent by God into trees. Thus, when a tree creaks on a windless night, it is in truth the weeping and crying of the penitent soul that one hears. One must then pray for them, mentioning Adam and Eve, and the soul will be pardoned and the tree will cease its creaking. It is said that souls in general inhabit old spruces, but more specifically, a girl's soul will pass into a linden or a birch while a man's soul will enter an oak, ash or alder. In general, all trees are holy save the aspen which is believed cursed because it was on that tree that Judas hung himself. This is directly related to our tale where the youngest daughter, the one who betrayed her father, is especially cursed and transformed into an aspen.

Another proof linking reincarnation with trees is found in the funeral laments which have served as a reservoir of on-going folk-belief up until this present century, In one, a mother addresses her dead daughter:

What kind of flower will you bloom in? What kind of leaf? What blossoms will you sprout when I walk by? How will I recognize you? How will I know you? Will you be in flowers? In leaves? (Šalčiūtė 1967:42).

A daughter cries for her mother:

.. .I will ask my brother that he would plant a birch on my mother's grave. When the cold storms will come, I shall go up the high hill to my mother's grave. The birch branches will enfold me like my mother's white arms. The north wind will not blow on me, the biting rain will not fall on me (Jonynas et al 1954: 522).

A daughter cries for her father:

Oh that a green plane-tree would grow from my father's grave. All the beautiful birds would then alight there, and would pick sweet berries. Oh, a mottled cuckoo would weep for you with her song (ibid.:52B).

And a mother laments for her. daughter:

Oh my dearest little daughter, Oh, how will you sleep in the black earth where the winds don't blow, where the sun doesn't shine. Only the cuckoo will cry. Only the little birds will sing in the white birch on your little grave! (ibid.:533).

Other than laments, many Lithuanian folksongs draw analogies between man and trees or plants. The usual epithet for a young girl is "white lily" and for a young lad it is "white clover." Constant parallels are also drawn between a young maid and a green linden and a young man and a green oak. As folksong scholars have marked, this type of parallelism usually enhances the songs' poetical quality and these traditional "formulaic expressions" may have persisted precisely because of their aesthetic appeal. Nevertheless, they seem to be instrumental in shaping the general world-view of the people who sing them and it is, therefore, not at all surprising that the Baits do feel this close identity with nature. The following Lithuanian folksong well illustrates this:

Oh dearest father, don't cut the birch growing near the road.

Oh my own true mother, don't fetch the water from the stream.

Oh my own true brother, don't cut the hay near the water.

Oh my own true sister, don't pluck the flowers in your garden.

The birch near the road is really me, the young one.

The water from the stream — my sorrowful tears.

The hay near the waters — my yellow hair.

The flowers in the garden — my bright little eyes.

(Balys 1948: II 64).

CUCKOO

It is interesting to observe that in many Baltic folktales, legends, songs and beliefs, women turn into cuckoos out of grief when they have been separated from ones they love. This motif constantly repeats itself in the laments where the mourner expresses a desire to turn into a cuckoo and "weep with its song." This belief is clearly reflected in those variants of the tale where the heroine becomes a cuckoo and her children become either trees or other birds.

Any attempt to demonstrate that the tale is a Baltic oicotype because of its close correlation to Baltic folk-beliefs becomes more difficult when dealing with these other motifs of the story. The power of a parent's curse, the transformation to some other form of plant or animal out of grief, even the idea of reincarnation in trees are not solely unique to the Baits but are found in other European folk traditions. What may be somewhat atypical is that among the Baits these beliefs are still widespread and constantly expressed to this very day and find reinforcement in songs and laments. It may then be argued that all of these factors help to imbue the story with a cultural relevance for the Balt which might not be so quickly perceived or deeply felt by a German or Slav. But it must be admitted that the case for these motifs, ie. trees, cuckoo, is not nearly so strong as that for the snake when discussing possible factors that would have limited the tale to the Baltic countries.

CONCLUSION

One conclusion that can certainly be drawn is that the motifs of the tale and their ultimate structure (ie. sequence of events) reflects many still very viable folk-beliefs which are generally known to most Baits. This would almost suggest that the tale is not as fantastical as it would first seem since it is so deeply rooted in a folkloric reality accepted by the people who relate it. Whether the story should therefore be considered a Sage rather than a Märchen (its usual classification by folktale scholars) is another matter.

The initial purpose of this study — to illustrate how folk-beliefs may be the laws which account for oicoty-pification of a folk tale — has been partially fulfilled. If one of the "laws" which affect the life of a story is the relevance which it may have for the people via various folk-beliefs and convictions, then that case has been well demonstrated. But whether this relevance simply enhances the popularity of the tale or is actually the crucial life-root which maintains the existence of the tale and restricts its migration requires much more substantial proof. If our analysis of the disintegration of some of the Latvian variants is valid and the general discussion of the folk motifs, especially the snake, is also of some merit, then perhaps our research is at least heading in the right direction.

🐍🐍🐍

Folktale Type 425-M: A Study in Oicotype and Folk Belief - Elena Bradunas

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 21, No.1 - Spring 1975

Editors of this issue: Antanas Klimas, Thomas Remeikis, Bronius Vaškelis

Copyright © 1975 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Lituanus

"IF YOU KILL A SNAKE — THE SUN WILL CRY"

Folktale Type 425-M

A Study in Oicotype and Folk Belief

ELENA BRADŪNAS

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Syncretism rambling under the cut

I seriously hope Type Moon doesn't use Barbara Walker's The Women's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets as a "factual and historical" source anymore than they already have. It was bad enough with the Norse-Celtic syncretism (of which was semi-popularized with Scathach-Skadi in SMT and used as basis for the entire Celtic pantheon in FGO) but some of the shit in this book is insane from a historical standpoint that you'd have to be a mental gymnastics olympic champion to get through those hoops of supposed logic.

Also, for the record, this isn't me bashing her because it's a feminist view on history and mythology. Honestly, that's an interesting fresh breath of air! But unfortunately, the contents of said book are incredibly bad regarding how much shit is made up/unfounded with what we actually have information on.

Some examples that I wish weren't actually in this book:

The excerpt on Aesir

"Asians," the Norse gods led by Father Odin, who invaded the lands of the elder deities (Vanir). The Aesir came from Asaland, or Asaheimr, meaning both "land of gods" and "Asia." Some claimed their home city was Troy. Such myths record the recurrent western migrations of Indo-European or Aryan peoples. The Norse word for a god was Ass, "Asian." The Egyptian god Osiris was formerly Ausar, "the Asian." Etruscans also called their ancestral deities Asians. Phoenician king Cadmus was "the Oriental," from kedem, "the Orient." The Asian invaders were aggressive. The Voluspa said war occurred "for the first time in the world" when the Aesir attacked the peace-loving people of the Goddess.

The excerpt on Aryans

General name for Indo-European peoples, from Sanskrit arya, a man of clay (like Adam), or else a man of the land, a farmer or landowner. The ancestral god of "Aryans" was Aryaman, one of the twelve zodiacal sons of the Hindu Great Goddess Aditi. In Persia he became known as Ahriman, the dark earth god, opponent or subterranean alter ego of the solar deity Ormazd (Ahura Mazda). In Celtic Ireland he was Eremon, one of the sacred kings who married the Earth (Tara).

Though there was nothing "pure" about either the name or the far-flung mixture of tribes it was supposed to describe, the term "pure Aryan" was revived in Nazi Germany to support a mythological concept of Teutonic stock, the so-called Master Race. Non-Aryans were all the "inferior" strains: Semites, N██████, gypsies, Slavs, and Latinate or "swarthy" people whose blood was said to be polluting the Nordic superiority of their betters.

The excerpt on Aladdin

Marco Polo described Aladdin quite differently from his mythic portrait in the Arabian Nights. As the fairy tale said, he was master of a secret cave of treasures, but the cave was real. It was located in the fortified valley of Alamut near Kazvin, headquarters of the fanatical brotherhood of hashishim or "hashish-takers," which Christians mispronounced "assassins."

Aladdin was an Old Man of the Mountain, hereditary title of the chief of hashishim, beginning with a Shi'ite leader Hasan ibn al-Sabbah, whose name meant Son of the Goddess (see Arabia). The later name of Aladdin was taken by several chieftains. In 1297 the region of Gujarat was conquered by a warrior called the Bloody One, Ala-ud-den. By means of drugs and an elaborate "paradise" staffed by human Houris, initiates into the brotherhood were persuaded that they died and went to heaven, or Fairyland, where gardens and palaces occupied the valley of the secret cave. Special conduits flowed with the Four Rivers of Paradise: water, wine, milk, and honey. Each candidate was drugged into a stupor, then woke and "perceived himself surrounded by lovely damsels, singing, playing, and attracting his regards by the most fascinating caresses, serving him also with delicate foods and exquisite wines; until intoxicated with excess of enjoyment amidst actual rivulets of milk and wine, he believed himself assuredly in Paradise, and felt an unwillingness to relinquish its delights."

After this period of bliss, the warrior was again drugged and taken out of the secret place, to fight in the service of the Old Man of the Mountain. He fought fearlessly, in the belief that death in battle would instantly carry him back to that heaven cleverly made real for him. Promises of sexual bliss were the real key to the ferocity of Islamic armies. The Koran said each hero who died in battle would achieve an eternity of pleasure among heavenly Houris with "big, beautiful, lustrous eyes."

Aladdin's sect worshipped the moon as a symbol of the Goddess, like the Vessel of Light associated with both the virgin Mary and the Holy Grail in western Europe. Eastern poets said the Vessel of Light produced djinn, "spirits of ancestors." This Vessel was simultaneously Aladdin's lamp, source of djinni (a genie), and the moon, source of all souls according to the most ancient beliefs. The moon was the realm of the dead, and also the realm of rebirth since all souls were recycled through many revolutions of the wheels of Fate. The divine Houris also dwelt in the moon, which probably was the light of Aladdin's secret cave. See Moon.

The Arabian Nights gave the password to Aladdin's cave: Open, Sesame. This was related to Egyptian seshemu, "sexual intercourse." The hieroglyphic sign of seshemu was a penis inserted into an arched yoni-symbol. Every ancient culture used some form of sexual symbolism for the idea of man-entering-paradise.

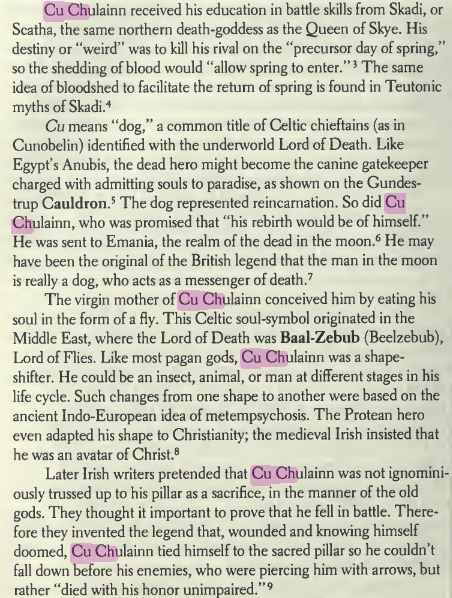

An excerpt on Cu Chulainn

The infamous excerpt on Skadi

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Questions about the English Language

Questions about the English language

Questions about the English Language, its origin, history and development, its major events and the reasons why it is so difficult to learn and to speak

1) What was the first Indo-European language to be spoken in Britain?

The first people in Britain about whose language we have definite knowledge are the Celts. Celtic was, therefore, presumably the first Indo-European language to be spoken in the country we now know as England.

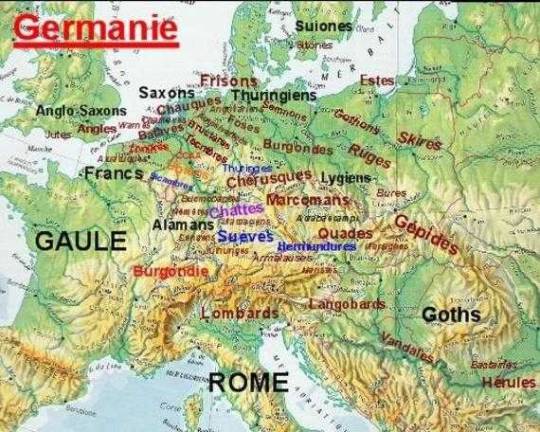

2) What were the Teutonic tribes that settled in Britain after the Romans had left it?

The Teutonic tribes which settled in Britain after the Romans had left it, were the Jutes, Saxons and Angles.

3) Where did the Jutes, Angles and Saxons come from?

Before crossing over to Britain, the Jutes and the Angles most probably had their home in the Danish peninsula; the Jutes in the northern half (hence the name Jutland) and the Angles in the South. The Saxons were settled to the south and west of the Angles, roughly between the Elbe and the Ems.

4) Where did these tribes settle?

First came the Jutes who settled in Kent, then, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Saxons who settled in Sussex and Wessex. Finally the Angles who occupied the east coast and then established an Anglian Kingdom north of the Humber.

5) What are the main periods in the development of English?

The English language of today is the language which has resulted from the fusion of the dialects spoken by the Jutes, Saxons and Angles. In the development of English, we generally distinguish three main periods. The period from 450 to 1150 is known as Old English. From 1150 to 1500 the language is known as Middle English. The language from 1500 to the present time is called Modern English.

6) What event is commonly considered to mark the beginning of the Old English period?

The invasion of England by Germanic tribes, notably the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes in the 5th century, marked the beginning of the Old English period.

7) Which famous medieval document played a significant role in shaping the English language during the Middle English period?

The Magna Carta, signed in 1215, played a significant role in shaping the English language during the Middle English period, as it was one of the earliest legal documents written in English rather than Latin or French.

8) Who is often credited with the translation of the Bible into English, contributing significantly to the standardization of the language?

The translation of the Bible into English by John Wycliffe in the 14th century is often credited with contributing significantly to the standardization of the English language.

9) What major historical event had a significant impact on the English language, leading to the borrowing of many French words into English?

The Norman Conquest of England in 1066 had a significant impact on the English language, leading to the borrowing of many French words into English.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r9Tfbeqyu2U

10) During which period did English start to emerge as a global language due to British colonial expansion?

English started to emerge as a global language during the Early Modern English period, particularly during the Age of Exploration and British colonial expansion from the 16th century onwards.

11) What influential English writer is often referred to as the "Father of the English Language"?

Geoffrey Chaucer, the author of "The Canterbury Tales," is often referred to as the "Father of the English Language" due to his significant contributions to English literature during the Middle English period.

12) What linguistic event occurred in the 15th century that marked the transition from Middle English to Early Modern English?

The Great Vowel Shift, a series of changes in the pronunciation of English vowels, occurred in the 15th century, marking the transition from Middle English to Early Modern English.

13) What has been the influence of the Bible on the English language?

The Bible has had a significant impact on the English language, particularly during the Middle English period when it was translated into English by figures such as John Wycliffe and later by the King James Version translators. The translation of the Bible into English helped to popularize the language among the masses and contributed to its standardization.

14) What has been the influence of Shakespeare's works on the English language?

Shakespeare is often credited with contributing a vast number of words and phrases to the English language, estimated to be around 1,700 words according to some sources. His plays and poetry have introduced countless idioms, expressions, and linguistic constructions that have become ingrained in the English lexicon. Additionally, Shakespeare's works have helped to standardize English grammar and vocabulary during the Early Modern English period.

15) What influential dictionary, first published in the 18th century, played a crucial role in standardizing English spelling and usage?

Samuel Johnson's "A Dictionary of the English Language," first published in 1755, played a crucial role in standardizing English spelling and usage.

16) Which two Germanic tribes had the most significant influence on the development of Old English?

The Angles and the Saxons had the most significant influence on the development of Old English.

17) What modern English dialect evolved primarily from the English spoken by early settlers in the American colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries?

American English evolved primarily from the English spoken by early settlers in the American colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries.

18) Why do you think the English language is so difficult to be learned well?

Because it has an extremely rich vocabulary, an irregular spelling system and a lot of idiomatic usages. As a matter of fact those five hundred words an average Englishman uses are far from being the whole vocabulary of the language. You may learn another five hundred and another five thousand and yet another fifty thousand and still you may come across a further fifty thousand you have never heard of before.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MqqlSb9uGUQ

To learn, to practice and to improve the English Language, the Use of Internet and Marketing Strategies write us, we can guarantee free advice, good tricks, useful cooperation, lot of materials and ideas. Find out more at the following links:

The English Language ;

The English language article ;

History of English ;

Short history of English ;

Diffusion of English ;

The blend of English ;

The power of English ;

The world of English ;

The world of English language ;

English words origin and vocabulary ;

Language and grammar ;

English Resources ;

George Mikes on English ;

English Literature ;

English History ;

Celtic languages ;

Questions on Colonialism ;

Language and Thought ;

Languages of the world ;

English the world language ;

On Facebook ;

World of English ;

Read the full article

#Angles#Bible#Britain#Chaucer#English#idioms#Indo-European#Johnson#Jutes#language#MagnaCarta#MiddleEnglish#ModernEnglish#OldEnglish#questions#Romans#Samuel#Saxons#Shakespeare#Shift#spelling#usage#vowel

0 notes

Text

Events 9.20

1058 – Agnes of Poitou and Andrew I of Hungary meet to negotiate about the border territory of Burgenland.

1066 – At the Battle of Fulford, Harald Hardrada defeats earls Morcar and Edwin.

1187 – Saladin begins the Siege of Jerusalem.

1260 – The Great Prussian Uprising among the old Prussians begins against the Teutonic Knights.

1378 – Cardinal Robert of Geneva is elected as Pope Clement VII, beginning the Papal schism.

1498 – The Nankai tsunami washes away the building housing the Great Buddha at Kōtoku-in. It has been outside since then.

1519 – Ferdinand Magellan sets sail from Sanlúcar de Barrameda with about 270 men on his expedition which ultimately culminated in the first circumnavigation the globe.

1586 – A number of conspirators in the Babington Plot are hanged, drawn and quartered.

1602 – The Dutch town of Grave held by the Spanish, capitulates to a besieging Dutch and English army under the command of Maurice of Orange.

1697 – The Treaty of Ryswick is signed by France, England, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire and the Dutch Republic, ending the Nine Years' War.

1737 – The finish of the Walking Purchase which forces the cession of 1.2 million acres (4,860 km2) of Lenape-Delaware tribal land to the Pennsylvania Colony.

1792 – French troops stop an allied invasion of France at the Battle of Valmy.

1835 – The decade-long Ragamuffin War starts when rebels capture Porto Alegre in Brazil.

1854 – Crimean War: British and French troops defeat Russians at the Battle of Alma.

1857 – The Indian Rebellion of 1857 ends with the recapture of Delhi by troops loyal to the East India Company.

1860 – The future King Edward VII of the United Kingdom begins the first visit to North America by a Prince of Wales.

1863 – American Civil War: The Battle of Chickamauga, in northwestern Georgia, ends in a Confederate victory.

1870 – The Bersaglieri corps enter Rome through the Porta Pia, and complete the unification of Italy.

1871 – Bishop John Coleridge Patteson, first bishop of Melanesia, is martyred on Nukapu, now in the Solomon Islands.

1881 – U.S. President Chester A. Arthur is sworn in upon the death of James A. Garfield the previous day.

1893 – Charles Duryea and his brother road-test the first American-made gasoline-powered automobile.

1911 – The White Star Line's RMS Olympic collides with the British warship HMS Hawke.

1920 – Irish War of Independence: British police known as "Black and Tans" burned the town of Balbriggan and killed two local men in revenge for an Irish Republican Army (IRA) assassination.

1941 – The Holocaust in Lithuania: Lithuanian Nazis and local police begin a mass execution of 403 Jews in Nemenčinė.

1942 – The Holocaust in Ukraine: In the course of two days a German Einsatzgruppe murders at least 3,000 Jews in Letychiv.

1946 – The first Cannes Film Festival is held, having been delayed seven years due to World War II.

1946 – Six days after a referendum, King Christian X of Denmark annuls the declaration of independence of the Faroe Islands.

1955 – The Treaty on Relations between the USSR and the GDR is signed.

1961 – Greek general Konstantinos Dovas becomes Prime Minister of Greece.

1962 – James Meredith, an African American, is temporarily barred from entering the University of Mississippi.

1965 – Following the Battle of Burki, the Indian Army captures Dograi in course of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.

1967 – Queen Elizabeth 2 is launched Clydebank, Scotland.

1971 – Having weakened after making landfall in Nicaragua the previous day, Hurricane Irene regains enough strength to be renamed Hurricane Olivia, making it the first known hurricane to cross from the Atlantic Ocean into the Pacific.

1973 – Billie Jean King beats Bobby Riggs in the Battle of the Sexes tennis match at the Houston Astrodome.

1973 – Singer Jim Croce, songwriter and musician Maury Muehleisen and four others die when their light aircraft crashes on takeoff at Natchitoches Regional Airport in Louisiana.

1977 – Vietnam is admitted to the United Nations.

1979 – A French-supported coup d'état in the Central African Empire overthrows Emperor Bokassa I.

1982 – NFL season: American football players in the National Football League begin a 57-day strike.

1984 – A suicide bomber in a car attacks the U.S. embassy in Beirut, Lebanon, killing twenty-two people.

1990 – South Ossetia declares its independence from Georgia.

2000 – The United Kingdom's MI6 Secret Intelligence Service building is attacked by individuals using a Russian-built RPG-22 anti-tank missile.

2001 – In an address to a joint session of Congress and the American people, U.S. President George W. Bush declares a "War on Terror".

2003 – Civil unrest in the Maldives breaks out after a prisoner is killed by guards.

2007 – Between 15,000 and 20,000 protesters marched on Jena, Louisiana, in support of six black youths who had been convicted of assaulting a white classmate.

2008 – A dump truck full of explosives detonates in front of the Marriott hotel in Islamabad, Pakistan, killing 54 people and injuring 266 others.

2011 – The United States military ends its "Don't ask, don't tell" policy, allowing gay men and women to serve openly for the first time.

2017 – Hurricane Maria makes landfall in Puerto Rico as a powerful Category 4 hurricane, resulting in 2,975 deaths, US$90 billion in damage, and a major humanitarian crisis.

2018 – At least 161 people die after a ferry capsized close to the pier on Ukara Island in Lake Victoria and part of Tanzania.

2019 – Roughly four million people, mostly students, demonstrate across the world to address climate change. Sixteen-year-old Greta Thunberg from Sweden leads the demonstration in New York City.

0 notes

Text

”The wolf has always been a symbolic beast of death and the secrets of the netherworld; Odinn is accompanies by his two wolves, Geri and Freki, and the Italo-Etruscan deity Hades was depicted wearing a wolf’s head as a headdress. The wolf is a dweller in the beyond, the wild dreams of the ghost-world and it is as ferocious and implacable as the jaws of death itself.

Thus those Indo-European magician-warriors who became wolves ‘died’ and were regarded as being wholly beyond the enclosure and laws of the ordinary world. Such warriors could kill with impunity and in like manner transgressors against the tribal code were cast out to the wilderness as outlaws - symbolically dead already any man could murder them without fear of redress. Thus in Teutonic lands the outlaw, criminal or desecrator of temples was declared to be a ‘Vargr i Veum’, a ‘Wolf in the Temple’ [...] criminals who hid in the forest were called ‘Wolfs-Heads.’ The saxons called the gallows ‘Wolf-Tree’, the ‘Varg-treo.’”

- Compleat Vampyre; The Vampyre Shaman, Werewolves, Witchery & the Dark Mythlogy of the Undead, Nigel Jackson

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

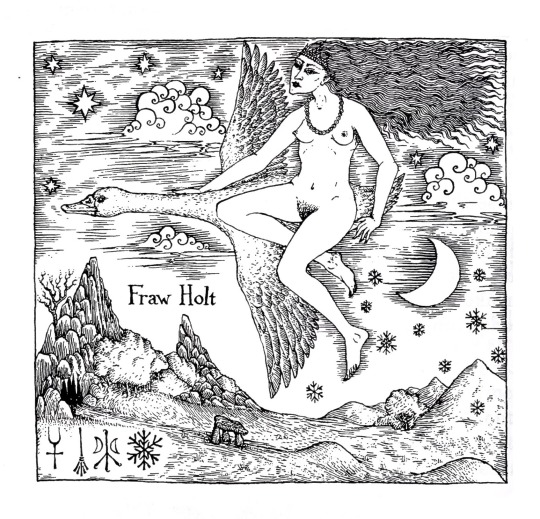

Fraw Holt or Dame Holda, the northern witch-goddess travelling upon her sacred goose through the night.

—

“Frau Holda , Venus Mountain and The Night Travellers

From the 10th Century c.e. onwards Frankish clerics and churchmen such as Regino of Prum fulminated sourly against the devilish ' belief of 'certeine wicked women that in the night times they ride abroad with Diana, the goddess of the pagans, or else with Herodias, with an innumerable multitude upon certeine beasts. This was echoed in the fourteenth century law-code of Lorraine which censured those who rode through the air with Diana. The image of the Wild Ancestral Goddess had a powerful influence upon the mediaeval imagination; the author of ‘The Romance of the Rose' wote that a third of the people have dreams of nocturnal journeys with Dame Habondia.

In Northern Europe, the sect of night travelling witches were held to fly through the sky in the retinue of the goddess Herodias or Holda, who leads the ancestral spirits of the Furious Horde in the winter months around Samhain and Yule. Like the Cymric goddess Cerridwen, Frau Holda is the archaic underworld Earth Mother, mistress of death, initiation and rebirth, who rules over the chthonic realm of Hel or Annwvyn. In Scandinavia she is known as Hela, the daughter of Loki, of whom it is related that half of her is fair and half black with decay. This signifies her bright and dark aspects as Freyja/Holda mistress of life and death. The Veiled Goddess encompasses the cosmic dualities of day and night, growth and dissolution, radiance and shadow. Her association with the Wild Hunt is strong in Germany where the ride of the death powers is sometimes called the Heljagd and in Normandy, Mesnee a Hellequin. The Indo-European original of this Witch Goddess is *KOLYO, 'the Coverer' the funereal Otherworld Queen of the Indo-European peoples from which figures as diverse as the Celtic Cailleach and Greek nymph Kalypso are descended.

The life/death aspects of Dame Hela were referred to by the German wizard, herbalist and crystal scryer Diel Breull of Calbach who confessed in 1630 that he had travelled to the pagan holy mountain, the Venusberg, 'four times a year, during the fast.' He had no idea how he got to the mountain. He then confessed he was a night traveller and 'the Frau Holle (to whom he travels) is a fine woman from the front but from the back she is like a hollow tree with rough bark. It was in Venus mountain that he came to know a number of herbs.'

This description corresponds with the female forest spirit called the Skogfru in Old Norse and the woodwife, birch maiden and wild damsel elsewhere who are beautiful women from the front but hollow behind like a rotten log. The woodwives are associated with the Wild Hunt, sometimes being pursued by Woden . (‘Woodwife’ and ‘woodwose’ both stem from the Saxon root-word ‘Wod’ - ‘wild, furious, enthused’). Like many native European initiation sites, the Hurselberg was regarded as the gateway to the underworld, the domain of Frau Venus, the classicized Freyja/Holda. From the Hurseloch cave on the mountain eldritch voices and wailing could sometimes be heard, for it led down into the magical realm of the goddess.

The mediaeval tale of Tannhauser is based upon this initiatory lore for he was a knight minnesinger (troubadour) who while riding past the cavern of the Hurselberg at twilight encountered the beautiful and entrancing Frau Venus, who took him below into the Otherworld regions to be her consort for seven years. In Scottish tradition a related pattern is exemplified by Thomas the Rymer, the thirteen century seer who met the Queen of Elfame beneath the Eildon Thorn and went with her into the world of Faery for seven years.

She gave Thomas a golden apple to eat which conferred the prophetic gift upon him. This is reminiscent of Woden's descent into the heart of Suttungr's mountain where he sleeps with the giantess Gunnlodd to attain the mead of poetic inspiration.

Such goddess forms are comparable to the shamanic Clan Mother of the nether-world in Siberian mythology. And we may note that the worship of the Northern Earth Mother Jord/Hlodyn was carried out at hills and mounds, symbols of the womb of the earth. The Furious Horde at Samhain is esoterically linked with the rune Haegl whose primal form ‘*’ represents the snowflake. This makes sense as Holda is traditionally held to shake down the snow onto the countryside; in the Channel Isles snow showers occur when Herodias shakes her petticoats. Her holy bird, the goose, is also connected with the Wild Hunt, and snow crystals are said to drift from its feathers as it flies overhead. The nocturnal cries of migrating geese are interpreted as the yelping of ghostly Gabriel hounds in Celtic lore and are symbolised by the Bird-Ogham Ngeigh at Samhain. The mystical Ninth Mother-Rune symbolises the nine nights the post-mortem soul takes to travel the Hel-Way, the prototypical Spirit-Road which runs northwards into the Underworld of Helheim.

Frau Holda is the heathen original of Mother Goose, who is remembered at winter tide, and the goose is the magical steed upon which Arctic shamans travel in visionary flight to the Otherworld. The witch Agnes Gerhardt confessed in 1596 that she and her fellow initiates used a vision-salve in order to fly to the dance like snow geese', and went on to describe how she prepared this hallucinogenie ointment by frying tansy, hellebore and wild ginger in butter mixed with egg. Such flying salves' (or Unguentum Sabbati) feature prominently in the worteunning of the night travelling witches.

In fact Styrian witches were still using them in the 19th Century. Hartliepp, court physician of Bavaria, gives a formula used by 15th century Northern witches which involves procuring seven herbs on the appropriate days of the pagan week - heliotrope on Sunna's day, fern on moon day, verbena on Tiw's day, spurge on Woden's day, houseleek on Thor's day, maidenhair on Freyja's day and nightshade on Saeter/Hela's day. This magical operation would ensure that the salve would be empowered with the energies of the principal heathen deities.

In 1582 the Archbishop of Salzburg's counsellor, the erudite mathematician and astrologer Dr. Martin Pegger, was arrested under the charge that his wife had flown with the night travellers to the goddess Herodias in the Unterberg. Within the mountain she had seen Herodias with her mountain-ladies and mountain-dwarves and the goddess is said to have come to Frau Pegger's house by Salzberg fish market on a later occasion. The mention of the goddess' mountain-dwarves is significant for they are sometimes known as the Huldravolk; the folk of the Elder, Frau Holda's holy tree.

The association of cats and hares with witches and night travellers may indicate that they inherited many of the magical techniques from the cult of Seidr, the shamanism of 'inner fire' sacred to the goddess Freyja which included trance journeys and communication with the elves and other entities. According to Saxon lore, Freyja sometimes appears amidst a company of hares and she is known to roam the meadows of Aargau with a silver-grey hare by her side in the night hours. The hare is famed as a totem form in which shapeshifting witches travel.

Freyja, the Teutonic goddess of love, sexuality and mantic sorcery riding a Siberian tiger.

It is know that a strong subterranean current of Freyja worship survived in mediaeval Germany. Closely related initiatory Mysteries existing in the British Isles usually centred on the Faerie goddess, the Queen of Elphame.

An interesting late case is the astrologer and Hermeticist John Heydon in the 17th century, who having imprudently predicted Cromwell's death was forced to flee from London to Somerset. There he claimed to have encountered a green- robed lady at a faery hill. She took him within the mount into a glass castle where he learnt much wisdom and mantic lore. This experience obviously took place in an altered state of shamanic perception.

Frau Holda is the feminine counterpart of the Master of the Wild Hunt, and she is essential to a balanced appreciation of this area of pagan spirituality. The night- travelling witches of the Northern Lands, far from being demonically deluded as ignorant and vindietive churchmen said, were in reality the preservers of a hoary Wisdom Tradition and magical world view which is now accessible to us again at the dawning of a new heathen aeon.”

—

Call of the Horned Piper

by Nigel Aldcroft Jackson

#call of the horned piper#Nigel aldcroft Jackson#magic#witchcraft#traditional withcraft#grimoire#fraw holt#dame holda

271 notes

·

View notes

Note

When you mention older scholarship that is "influenced too much by structural linguistics", I would very much like to understand in better detail what you mean. Thanks in advance, D.

I know I said that recently and now I’m blanking on when and what the context was, so I’m not sure if this answer is going to be totally relevant. Also, just to make this clear, what this is isn’t actually a problem with structuralism, it’s just structuralism done incredibly badly.

Usually what I mean by something like this is “Dumézil and his influence.” I have caught myself saying that when what I really mean is treating Norse religion and/or mythology like it’s comparative linguistics which is a related problem, and Dumézil did that too (i.e. Týr and Jupiter are cognate, therefore we can reconstruct the original), but not exactly the same thing.

In structuralism, something only has meaning insofar as it forms meaning in relation to other things. There’s nothing about the letters “cat” or the sounds [kʰæt] that are inextricably linked to feline animals, it just has that meaning because we have a lot of people who speak languages wherein that spelling, those sounds, and the idea of those creatures have been codetermined into place. I personally agree with all that. The problem is that a lot of the early Norse scholars who applied structuralist analyses to myth and religion were just really, really bad at it. There are modern scholars (e.g. Jens Peter Schjødt) who do make effective use of structuralist analysis.

Here are some of the ways they dropped the ball. It starts with the inability to demarcate the system under observation. If you already assume that “Teutonic culture” was a thing, and that it’s reconstructable, then yeah, it does follow that you could do a structural analysis where you’re measuring gods against each other in order to better understand each of them individually by the comparison. But that just wasn’t a thing. You can’t just take it for granted that Nerthus and Óðinn occupy the same system, and that a structure consisting of Nerthus can be used to analyze Óðinn’s relationship to the Völsungar clan, for example. This is where this poor attempt at structuralism intersects with the other problem I mentioned, treating religion and mythology like you can use the rules of comparative linguistics to examine it.

If we scale up from this, we see the assumption that structural relations within Norse culture also apply to Indo-European culture generally. This is another example of that same etymological essentialism. Why would these unarticulated, unspoken, underlying “structures” persist over time, with no description of how they are preserved and transmitted, and furthermore, why would they follow linguistic distribution? All this is left unclear. A good structuralist would point out that this is a conflation of synchronic and diachronic structural relations.

But then there comes the problem that makes these harder to observe: circular reasoning. When these techniques are used to create self-fulfilling prophecies, evidence is selected and rejected based on whether or not it supports the hypothesis, then people like Dumézil get to go “see! It must be true, because my theories accurately predict and describe [this body of evidence that I hand-picked to fit the prediction].”

Notably, Dumézil was heavily criticized by other structuralists (e.g. Claude Levi-Strauss) so really it might be less of a legitimate criticism to say that it was “too influenced by structural linguistics” and better to say something about structuralism being applied poorly, without enough regard for actual evidence, with conflation of diachronic (historical) and synchronic (contemporary, spontaneous, within the then-existing system) axes of relations, and in an academic context already distinguished by weird etymological essentialism providing them with even worse fake evidence.

20 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The wolf has always been a symbolic beast of death and the secrets of the netherworld; Odinn is accompanied by his two wolves, Geri and Greki, and the Italo-Etruscan deity Hades was depicted wearing a wolf’s head as a headdress. The wolf is a dweller in the beyond, the wild realms of the ghost-world, and it is as ferocious and implacable as the jaws of death itself.

Thus the Indo-European magician-warriors who became wolves ‘died’ and were regarded as being wholly beyond the enclosure and laws of the ordinary world. Such warriors could kill with impunity and in like manner transgressors against the tribal code were cast out into the wilderness as outlaws – symbolically dead already any man could murder them without fear of redress. Thus in Teutonic lands the outlaw, criminal or desecrator of temples was declared to be a ‘Vargr I Veum’, a ‘Wolf in the Temple’ whose life was considered forfeit and right down to the Middle Ages condemned criminals who hid in the forests were called ‘Wolfs-Heads’. The Saxons called the gallows the ‘Wolf-Tree’.

Nigel Jackson - The Compleat Vampyre: The Vampyre Shaman, Werewolves, Witchery, & the Dark Mythology of the Undead

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Question for Nordic People on Tumblr

Is there a difference between Scandavian and Teutonic people in regards to early pagan religions, and if so, what are they? I was under the impression that they were very nearly the same (sharing the same Indo-European roots) and someone (a Norwegian) called me an idiot American for equating them.

Sincerely,

The Idiot American

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manifesto of mind & mysticism:

Where spirituality meets empirical science.

I traverse the collective unconscious.

I share musings on the magical; metaphysical & mystical

I have been practicing daily ceremonial ritual magick for more than 8 years and am a lifelong psychic, trained in Kardec Spiritism and Mediumship from childhood.

As a daughter of high ranking freemasonic/secret societies of both “LHP/RHP” rites, lodges & paths. . That’s the beginning of my authentic and real line of ancestors.

(I can prove all I speak of).

I consider myself a spiritual dichotomy.

But I’m still a real, raw & passionate being of energy in motion (emotion).

So to commune these lost ancestral traditions & revive them into reality. Is imperative. I aim to revive lost currents that can help humanity heal.

Growing up as a young woman carrying ancestral trauma I found spirituality was a never ending constant that kept me alive. I was always psychic but my daily practice of initiatio based ceremonial magick started in 2013. As a method to heal, help, protect & bring my higher self & manifest my great work in the world.

I’ve had a various disposition of unique experiences I want to share.