#Jim Ruland

Text

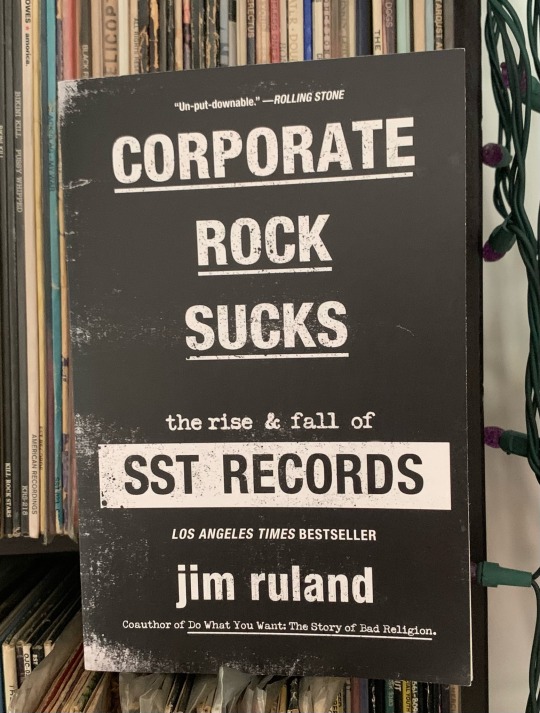

getting started reading this Christmas gift today, I’ve been wanting to check out Jim Ruland’s Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST Records for awhile now

#sst records#Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST Records#Jim Ruland#sst#read a book#book#taken by me

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#sst records#greg ginn#black flag#Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST Records#negativland#Jim Ruland#the new republic

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Reckless, the graphic novel series from the award-winning team of Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips, gets the spotlight in this feature story by the L.A. Times. Jim Ruland, author of Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records talks with Brubaker about ‘80s L.A., mining his personal history for the story and updating the lurid detective series his father used to read for the new century.

“I can’t believe how lucky I was to get this feature, and how much art they’re running from the books, as well,” Brubaker said in his email newsletter. “This is actually the first L.A.-specific press the books have gotten, and since they’re basically a love-letter to the L.A. of my past, it means a lot.”

Read more

#ed bruabker#sean phillips#reckless#reckless: follow me down#graphic novels#jim ruland#l.a. times#three things#smash pages

1 note

·

View note

Note

do u have any book recs for punk history?

As far as books I’ve read, no I dont, BUT I do have a link to all 80 issues of Punk Planet, a zine based out of chicago that focused more on punk culture rather than music!! (Honestly I recommend browsing it)

I did do a bit of quick researching to find a list of books that may be what you’re looking for though:

Punk Rock an Oral History by John Robb & Oliver Craske (it spans a few decades and I actually kinda want to get this one now lol

Straight Edge: A Clear-Headed Hardcore Punk History by Tony Rettman

The Rise and Fall of SST Records by Jim Ruland (a label founded by Black Flag member Greg Ginn)

SELLOUT: The Major Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore 1994-2007 by Dan Ozzi (more recent history)

NYHC: New York Hardcore 1980-1990 by Tony Rettman (a little more local to north east America)

#mail tag#i really need to read up more on history#most of my brain stuff comes from zines and research online#but I’d like to have more punk books in my collection#that being said - I think dystopian novels should count I have a fuck ton of those

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

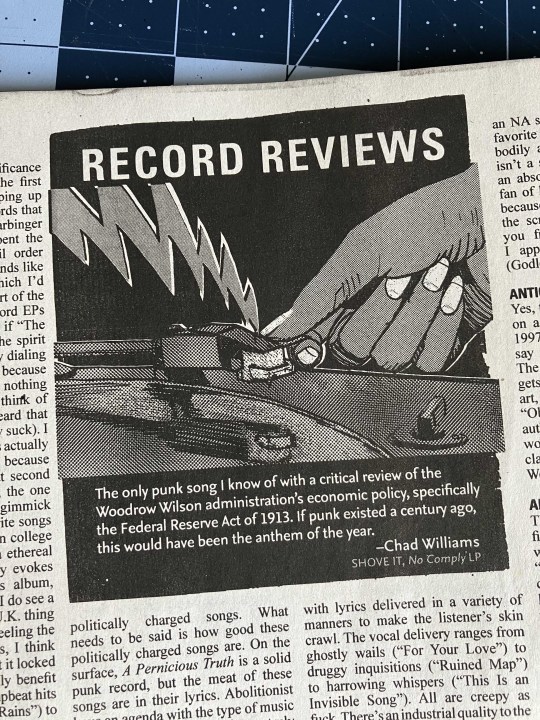

I contributed an illustration for @sean.carswell ‘s column which included a reference to the band @monstertreasureupyours in the latest issue of @razorcake_zine as well as a few illos in the reviews section. I will be taking part of a panel discussion on RC137 on Friday Jan 12 at @thepophop info below

IMPORTANT – PLEASE NOTE THE VENUE CHANGE.

Just a reminder of this event happening this Friday, Dec. 12!

An Exploration of Razorcake #137 at The POP-HOP

Panel + Discussion + Q and A

Featuring: Melissa Cody, Kiyoshi Nakazawa, Jim Ruland

Hosted by Razorcake co-founder Todd Taylor

Free!

Fri., Jan. 12, 2024

7PM

The POP-HOP

5002 York Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90042

Melissa Cody is an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation. She was born 1983 in No Water Mesa, Arizona, is a fourth-generation weaver, and a dyed-in-the-wool punk rocker.

Kiyoshi Lucky Nakazawa is a L.A.-based artist in the fields of animation, illustration, comics, and story boards. He graduated from Art Center College of Design in Pasadena with a BFA in Fine Arts. He is a regular comics column contributor to Razorcake magazine.

Jim Ruland is the author of the award-winning novel Make It Stop. He is the author of Corporate Rock Sucks, The Rise and Fall of SST Records. He is also the co-author of Do What You Want: The Story of Bad Religion and My Damage with Keith Morris.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Has anyone read Make It Stop by Jim Ruland? The summary on Rare Bird Lit piqued my interest.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jim Ruland Interview

Jim Ruland is a writer living in Southern California. His latest book is Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records.

Corporate Rock Sucks traces the history of Greg Ginn and SST Records. Originally founded as an electronics company, SST morphed into a record label to release material by Ginn’s band, Black Flag. Joe Carducci joined SST in 1981 and the imprint took off, becoming arguably the most influential independent label of the 1980s. Releases such as Black Flag’s Damaged (1981), Hüsker Dü’s Zen Arcade (1984), The Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime (1984), Meat Puppets’ Meat Puppets II (1984) and Sonic Youth’s Sister (1987) cemented the label’s status. A series of self-inflicted wounds, distributors going bust and key personnel loss—including Carducci and Steve “Mugger” Corbin—caused SST’s effective demise by 1991.

Ruland exhaustively covers the successes and failures of SST in Corporate Rock Sucks. He provides portraits of SST’s owners and contributors and goes deep, interviewing the behind-the-scenes employees who made SST run. SST didn’t end well. To this day, there remains acrimony between some artists and the label, which makes Ruland’s book all the more impressive. It wasn’t an easy story to tell. Corporate Rock Sucks is a must have for anyone remotely interested in independent music.

Interview by Ryan Leach

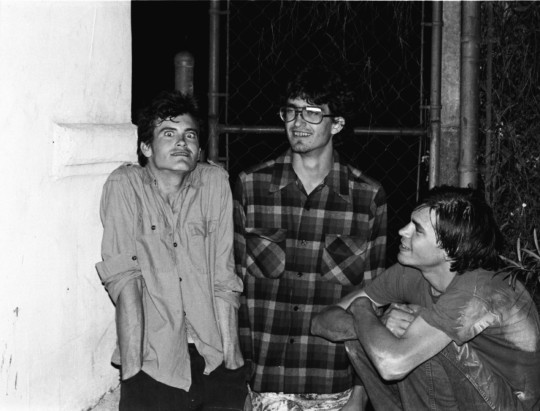

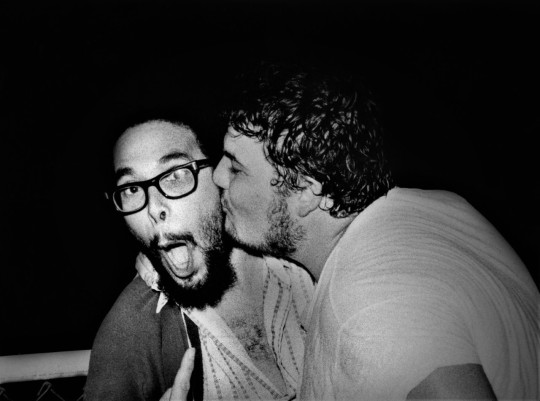

Photos courtesy of Jim Ruland

Ryan Leach: When did SST Records first come to your attention?

Jim Ruland: It came very late. I’m 53 years old, so I graduated high school in ’86. That was the year Black Flag broke up. When I got into punk music, it was when I was in the Navy, right after high school. I was in San Diego. I listened to Devo and The Ramones. I saw The Ramones in Washington D.C. I thought of myself as someone who liked weird music, so I kept it to myself. I didn’t know there was a tribe of other people out there. I just knew that what I liked wasn’t popular. That includes other things like Dungeons & Dragons. Once I started writing for Flipside and really getting into the punk scene in Los Angeles, SST had already passed its heyday. I was into more underground labels like Hostage Records. This was around 2000 when I moved to Manhattan Beach. By that time, I already had (The Minutemen’s) Double Nickels on the Dime (1984), Sonic Youth’s Sister (1987) and Negativland’s Escape From Noise (1987). I didn’t think of SST as hugely vital at the time. At that point, I thought of it as a big indie whose time had come. It wasn’t until I started working with Keith Morris (on My Damage) that I really became interested in SST as a label.

Ryan: I didn’t realize how pivotal working with Keith on his memoir was to Corporate Rock Sucks.

Jim: Yeah. The other part of that is—when I moved to Manhattan Beach, living in the South Bay, I thought, “Okay, this is different.” I grew up on the East Coast and I didn’t come out to the West Coast until I joined the Navy. I began to understand that the South Bay wasn’t like the rest of Los Angeles. It wasn’t like Santa Monica, Venice or Malibu. It was a whole other thing. The more I learned about SST and Black Flag, it all started to make sense to me. I felt like that element was missing in other books about Black Flag and SST. For example, how are people in England going to know the difference between Hermosa Beach and Huntington Beach? They don’t. It’s all the same thing to them.

Ryan: What were some of the hurdles you encountered writing Corporate Rock Sucks? Obviously, the focal point of the book, Greg Ginn, isn’t known for his communication skills these days. Additionally, like some other ‘80s indie labels—SST certainly isn’t alone here—some people still harbor resentment towards the imprint.

Jim: I think you hit it on the head. I didn’t want to get sued by Greg Ginn or SST. The books I did with Keith and Bad Religion (Do What You Want: The Story of Bad Religion) went through legal reviews, so I had enough experience with that to know what I could and couldn’t say. But even then, I wanted to be extra careful. What I didn’t count on was that other people needed to be careful too. They had either ongoing legal matters with SST or they had legal issues that had been settled out of court. There were a number of people who didn’t want to go on the record saying anything negative about Greg Ginn or SST. The first few people I reached out to either said “no” or didn’t get back to me. I began to wonder what I had gotten myself into. Then I did what I always do. When you sell a book to a mainstream press, and I guess to some extent with indies as well, people are concerned with big names. “Who’s going to help you attract attention to this book?” I’ve never been interested in that. Like you, I’m more interested in the things very few people are into. I took a different approach. I tried to find the people who had never spoken with anyone. I looked for the folks whose names weren’t well known, but who were there.

Ryan: Who were some of the people who really came through for you?

Jim: So many people. The first one was Mugger (Steve Corbin). He opened the door. I should say that I started with a list of people and their email addresses from Keith Morris.

Ryan: Keith did the same thing for me when I was researching The Gun Club.

Jim: Keith is the best. If you’re into something, he isn’t angling for himself. He just wants to help. All of the former SST employees I talked with were great. Brian Long really came through. Virtually everyone I talked to passed the word onto somebody else. In terms of musicians, I talked to a lot of drummers and they were great. Maybe it’s because people don’t seek out the drummers right away. They want to talk to the vocalist or guitar player. The drummers all had a lot of interesting things to say.

Ryan: When I encounter people who haven’t been interviewed before, I typically find that they’ve been waiting to talk and have very thoughtful responses.

Jim: I definitely found that to be true. Sometimes when you interview someone, they’re holding back because they want to do something themselves. I didn’t encounter any of that with this book. People were very open with me and they had an emotional response to the material. For the people at SST, it was either the best time of their lives or somewhat traumatic. People have been frozen out because of their bad relations with the label.

Ryan: You did a great job finding secondary sources for your book, specifically with past Greg Ginn interviews. You went way back to the late 1960s and Ginn’s early years running SST Electronics. How did you track this material down?

Jim: There were some clues. Joe Carducci in his book, Enter Naomi (2007), had talked about it. Mugger and Keith had both discussed their memories of soldering equipment for SST at The Church. They did it for extra money and to help out Greg. In the early days of Black Flag, they’d often have band practice and then solder equipment afterwards. The two things sort of went hand in hand at the beginning. Once I had Ginn’s call sign, I was able to find other material.

I’m not an electronics guy or gear guy in general. So, when I started to do some of the research at the beginning, I was kind of intimidated by the devices Ginn was making. “What were these things?” Ginn received a patent for one of his products. There was some technical stuff I had to understand. I marveled that a kid (Greg Ginn) was able to decode all of this lingo. He started up a business that was selling gear to adults. This was back in the late 1960s. In the South Bay with the way the aerospace industry was taking off—you had a lot of people like Ginn’s dad (Regis) who were World War II veterans. These were the people Greg was conversing with on his amateur radio setup. I thought, “This kid is different. He’s not your typical teenager.”

Ryan: I felt that you treated Ginn judiciously. It’s important to remember how precocious Greg and his brother Raymond (Pettibon) were, as well as how left of the dial the Ginn family was.

Jim: I found people on both sides of the spectrum. There were people who had nothing but respect for Ginn with no animosity whatsoever. They would sometimes be upfront at the beginning. “Look, things didn’t work out in the end, but we also didn’t sell a lot of records. So there’s no reason for me to hold a grudge. Greg was the one who made our dream possible.” There are other people who feel quite differently. They feel harmed by him and the label. That actual theft took place. There are two different realities there. It came down to the band and at what point they interacted with the label. I don’t think painting Ginn with a one-color brush works in this story. I didn’t have an axe to grind. I wasn’t setting out to prove that Ginn was some sort of genius—although I think he is—and I wasn’t trying to prove that he was some kind of monster. I just told the story that I found.

The Meat Puppets

Ryan: Until Joe Carducci joined SST in 1981, it seemed that the label was a part-time concern for Black Flag to get their records out, as well as albums by their friends in bands like The Minutemen and Saccharine Trust. Would you say that it was Carducci who turned SST into a full-time operation?

Jim: I think that’s right. Also, to a lesser extent, it was Carducci and his money. He had money that he had invested that allowed SST to put out some more records that were in the pipeline. Carducci also had a partner who was a co-investor in the first or second Meat Puppets record. It was a small scene where everyone did everything. When Black Flag hit the road—which became a bigger necessity as their infamy grew with the LAPD—they needed someone like Joe Carducci to come in. I had a lot of respect for Joe as a writer going into the project. But I really came to appreciate what he did running SST. He brought his experience to the label. Joe had worked with distributors and recruited talented people. Mugger was the most important person they brought in first, then Carducci and next I would say Ray Farrell.

Ryan: Hindsight is 20/20. But reading Corporate Rock Sucks—and I believe Carducci mentions this in Enter Naomi—the Unicorn/MCA distribution deal was recognized by some at SST in real time as being a potentially disastrous decision.

Jim: Yeah. One naturally wonders, “Why did SST do that?” But it wasn’t something they did capriciously. They had literally been vacated from their spot by the LAPD when they had been on tour. They came back and they had nowhere to go. They were staying at a punk house in Hollywood, making calls out of payphones and doing business that way. They needed a place. That’s why when they had the opportunity to go to Unicorn—even though there were some potential warning signs that it wouldn’t be a good idea—it was because they had nowhere else to go.

Ryan: So, would you frame the decision as one made out of necessity and desperation?

Jim: Maybe desperation is a little too dramatic, but they were literally homeless, aside from living at Greg Ginn’s parents’ house. That was Rollins’ introduction to SST and Black Flag. They’d ask each other questions like, “Where are we going to eat? When are we going to practice again? We don’t know.”

Ryan: In the book, you include a photo of Black Flag with a newly joined Henry Rollins signing their Unicorn deal. He was living in Regis Ginn’s detached library, which Rollins refers to in Get in the Van as “The Shed.”

Jim: Apparently, there was some irritation by Ginn’s family over that. They didn’t like it being called “The Shed.” It was a little more than that with a power supply and lots of Regis’s books. It was more like a study. But from the outside, it did look like a shed.

Ryan: I’ve never been able to figure out how and why SST released so many records in 1987 and 1988. You mention the label putting out nearly 70 releases in 1987. Was it the success of The Bad Brains’ I Against I (1986) that helped bankroll some of it?

Jim: Once they got clear of Unicorn, they started making some money and putting things in the pipeline. That’s when they were able to have multiple successes. I Against I was the main one. I was told that was the biggest-selling album in the catalog by that point. But Sonic Youth and Hüsker Dü had also been successful. SST was growing and growing. It got to the point where Negativland sold 35,000 copies of Escape From Noise (1987). That’s the number I heard.

Ryan: That’s nuts.

Jim: It’s crazy, right?

Ryan: That’s the number a top-tier act on a successful independent label moves nowadays.

Jim: Right. No disrespect to Negativland—I think that’s a brilliant album—but they’re not a rock band.

Ryan: It’s esoteric music.

Jim: Exactly. I think they were brilliant at what they did. If you go back to tape splicing and some of the other experimental things that were happening in the analog era, it’s very easy to end up with something closer to Zoogz Rift than Negativland. No disrespect to Zoogz; it’s just that Negativland brought what they did to a high art. I think it was a case where SST was having sales on multiple fronts, which allowed them to grow at the rate that they did. With distribution, you needed constant releases to bring the money in. You’d have distributors holding out on you and angling for exclusive deals. They’d withhold payments. To get them to pay, labels could play the same game: “We have this new Hüsker Dü record and you’re not going to get it until we get paid.”

Spot with D. Boon

Ryan: Digressing back a bit, one of the things SST handled well was monitoring recording costs. They understood that running up studio bills could sink the business. Can you talk about that aspect of the label and the deals they struck with studios like Total Access?

Jim: It starts with Spot (Glen Lockett). He was the one who introduced Greg to Media Art. It was right down the street, also in Hermosa Beach, and bands like The Plimsouls were recording there. It wasn’t a garage; it was a recording studio. One of the things that surprised me, and I can’t recall if I put this in the book or not, but when Spot moved to Hermosa, he was homeless. He was working at a restaurant and writing record reviews. It wasn’t until he got that gig at Media Art and the people there understood his situation, that he had a place to stay for a bit. They were okay with him crashing at Media Art because they had had some break-ins. The owners gave Spot the keys and he spent his time figuring out the equipment. He learned how to record on the job. That was key because Spot would later share that knowledge with others. On an SST release it’ll say, “Produced by so-and-so,” but my suspicion—and this is just my opinion—was that it was a more collaborative process than we were led to believe. There were a lot of people working together in the interest of time and minimizing expenses, as you alluded to.

Media Art closed down and Wyn Davis opened up Total Access a short time later. One of the things Greg Ginn did with Total Access was strike a deal where they agreed on a bulk rate for a certain amount of hours. That allowed SST to record without waiting for money to come in; they’d already paid in advance. That made a huge difference. It was savvy decision by both Total Access and SST.

Ryan: Getting back to what we had just discussed, SST in ’87 and ’88 was putting out on average a little over five releases a month. You mentioned the success that they had experienced once freed up from the Unicorn debacle. But I posit that the seeds of the label’s demise can partially be found in that release schedule. It was way too much and I know Carducci had left in ’86, which didn’t help matters.

Jim: That decision to put out all of those records is what partially soured Sonic Youth on SST. And then when their statements and payments were late, according to Sonic Youth, that deepened the rift. Sonic Youth’s departure was much to the detriment of SST. So why did they release so many records? When Carducci, Mugger, Dukowski and Ginn were the four owners, they all had veto power over each other. By that time you had Ginn and Dukowski in one office and Mugger and Carducci in another. So, there was this split where they were thinking a little bit differently and they weren’t always in sync with one another. It happened naturally; they were working out of two different locations. Carducci points out over and over again in interviews that the first problem was splitting the office up like that. They should’ve all worked together at the same location to stay on the same page. But they didn’t. When Carducci left, I think Ginn said, “Okay, this is my label now. And we’re going to do what I want to do.” And what Ginn wanted to do was release a shitload of records. My opinion is that Ginn felt so handcuffed by the injunction and lawsuit with Unicorn that when he was finally free of it and had some cashflow, his position was, “We’re going to hit the gas pedal and show them what SST is about.”

Ryan: They weren’t the only label doing that. Cherry Red would put out a lot of records and later on Sympathy had a heavy release schedule. But Sonic Youth had a point. If SST was going to put out all of those records, how would their own albums stand out against the glut? How could the label effectively promote all of those releases? Most records lose money and they were putting out a lot of them. You mention Ginn’s tenure at UCLA pursuing a degree in business and he certainly had moments of brilliance. But that ’87 and ’88 run of records seemed like a suicide mission.

Jim: Like you, most people point to that as the beginning of the end. People wondered, “Why all this stuff?” There’s also another element to it. There’s a contrarian streak to Ginn. One of the mistakes people make in regards to Ginn, SST and Black Flag is that they view them in monolithic terms. “Black Flag invented American hardcore.” You can make an argument for that. But by 1984, with side two of My War, hardcore is not a musical project Black Flag has any interest in. They went on from there into more and more experimental things. The simple answer is that Ginn had varied and wide tastes that were constantly evolving. And he wanted to take the label with him.

Ryan: That’s a good point. You can see that in superficial ways, like Rollins and Ginn growing their hair long or Ginn wearing Grateful Dead shirts to hardcore shows. Ginn seemed indifferent to people’s opinions.

Jim: My feeling is that when he went to Europe and saw the punk-rock uniform—the mohawks, leather and boots—Ginn wanted out of that scene completely.

Ryan: There were other setbacks. Their distributor Jem went out of business in 1988 which was a major loss. Then Mugger, SST’s factotum, left the same year. If I’m not mistaken, another one of SST’s distributors folded before Jem did.

Jim: Yeah, Greenworld was the other distro. I wish I understood that aspect of the story better. Greenworld was located right up the street in Torrance. Enigma Records came out of Greenworld. It’s fascinating that this distributor, Greenworld, is paying very close attention to SST and New Alliance and is able to succeed for a while with their own label.

Ryan: Interestingly, Enigma is another label whose catalog is severely neglected. Tex and the Horseheads, Rain Parade and a myriad of other artists have had records in purgatory for years. Some got their music back, others haven’t. It appears to be a similar situation to SST.

Jim: Right.

Ryan: I realize its speculation on your part—Ginn doesn’t give many interviews theses days—but do you think he realized the potential ramifications of releasing Negativland’s “U2” EP (1991)?

Jim: I think he did. It’s 1991. MTV is nothing new. Music is being licensed for commercials. There were people coming to SST, asking for permission to use their music for different projects. SST knew what you could and couldn’t do. But there’s that contrarian streak with Ginn. He didn’t care. The gentleman who was hired as SST’s general manager, Daniel Spector, his story about that Negativland EP blew my mind. Is it possible that that story has gotten more dramatic after 30 years of storytelling? Sure. But it goes back to the way I structured the book. Here was this ambitious, savvy and not to mention brilliant guitar player—we haven’t even talked about Ginn’s musicianship—and somewhere along the line, he lost the plot and SST went sideways. But that couldn’t be further from the truth. What I found was someone who faced obstacles at every stage of Black Flag and SST’s growth and development and didn’t back down from a single fight, even when he knew there was very little chance that he could win.

Ryan: That’s an interesting position. If you go way back to the Polliwog Park show (July 22, 1979) and other things along the way, you can see how that contrarian streak worked for and against him—sometimes it depended on the audience.

Jim: Yeah.

Ryan: The Negativland fallout was him shooting himself in the foot for four years straight with his manifestos and press releases.

Jim: I think he’s that same person today.

Ryan: You close the book on a positive note—advocating for artists’ work to be returned to them. Unfortunately, I don’t see SST doing that voluntarily. What’s the latest on that situation?

Jim: I hope I’m wrong, but I don’t think there’s going to be some sweeping SST declaration stating, “We’re going to give everything back to the artists.” I’m not an investigative journalist. I just told the story I found, talking with people and digging through zines from 40 years ago. I don’t know how much money Ginn makes from SST these days. I’m uncertain if public documents would shed light on this. Joe Carducci speculates in his book—it might have been in his newsletter—that Ginn has made more money on his real estate deals than he has selling records. Ginn bought a series of spaces in Long Beach, California, and when he sold them, he likely made a small fortune. I really don’t know what motivates Ginn artistically or financially today. I think making a blanket move where he gives the rights back to everyone probably exposes him to some kind of financial risk. People will naturally go, “Well, that’s great. But where’s the money owed to us?” I do think it’ll be handled on a case-by-case basis. Recently, I did speak with an artist who was able to buy back their music from SST.

Ryan: You mention there being questions about the location and condition of the master tapes themselves.

Jim: Something just happened which I found to be really interesting. It wasn’t with SST, but Cruz Records—one of Greg Ginn’s labels. Long story short, a guy reached out to me who has a studio in Long Beach. He found some old tape cases for masters. They were found in the studio’s storage attic and it confirmed his suspicion that the space was Ginn’s old recording studio, Casa Destroy. I interviewed him just yesterday; he had reached out to SST. He said, “Hey, I have these tape cases. I’d be happy to ship them to you if you’d like.” Ginn asked, “Are the master tapes in them?” And he responded, “No. It’s just the cases.” Ginn replied, “Well, no, we don’t want them.” What’s unusual about that is—you’d think they’d know where the master tapes are located. That’s just me speculating. No one really knows. I’ve heard all kinds of rumors of people in the SST universe sitting on stashes of master tapes.

Ryan: Didn’t short-term Black Flag drummer Emil Johnson take off with some master tapes back in the early 1980s?

Jim: He did. I interviewed Mugger’s former girlfriend. She told me that master tapes had been stored in her closet for over a year. I’m just speculating, but what that tells me is that those tapes weren’t safe and secure at SST. But then, how could they be if they were constantly moving around from place to place? There are people who look at Ginn as some arch villain and that this was his scheme all along. I don’t think that’s true. Things just got out of hand. I don’t mean to exonerate or make excuses for him. But there’s a good chance that Ginn doesn’t have the masters to all of those records. It wasn’t some Machiavellian plot. Yes, artists signed terrible contracts. But I think that’s just the contract that he had.

Ryan: What’s going on right now, Jim? I know you’re working on a book with Evan Dando.

Jim: Yeah, I have a draft of that I’m getting ready to send to my agent. We’ll see how that goes. I also write fiction. I have a novel in the pipeline that I’m excited about. I’ve been working on it for a very long time. I won’t call it a punk book, but it’s punk adjacent. It’s a dysfunctional, vigilante story with a lot of alcoholics, drug addicts and a couple punk rockers in it. It’s called Make It Stop and it’s coming out on Rare Bird Books in February of 2023.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

El Sistema de Bibliotecas Públicas de Los Ángeles se aventura en el mundo de la edición de libros.

Ruland, Jim. 2024. «The L.A. Public Library Is Getting into Book Publishing. Why It Makes Total Sense». Los Angeles Times. 8 de enero de 2024. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2024-01-08/the-l-a-public-library-is-getting-into-book-publishing-why-it-makes-total-sense.

El Sistema de Bibliotecas Públicas de Los Ángeles (LAPL) se ha iniciado en la publicación de libros,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

840. Jim Ruland

Jim Ruland is the author of the novel Make It Stop, available from Rare Bird Books.

Ruland is the co-author of Do What You Want with Bad Religion, and My Damage with Keith Morris, the founding vocalist of Black Flag, Circle Jerks, and OFF! Ruland has been writing for punk zines such as Flipside and Razorcake for more than twenty-five years and his work has received awards from Reader's Digest and the National Endowment for the Arts.

***

Otherppl with Brad Listi is a weekly literary podcast featuring in-depth interviews with today's leading writers.

Available where podcasts are available: Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, iHeart Radio, etc.

Subscribe to Brad Listi’s email newsletter.

Support the show on Patreon

Merch

@otherppl

Instagram

YouTube

TikTok

Email the show: letters [at] otherppl [dot] com

The podcast is a proud affiliate partner of Bookshop, working to support local, independent bookstores.

www.otherppl.com

0 notes

Text

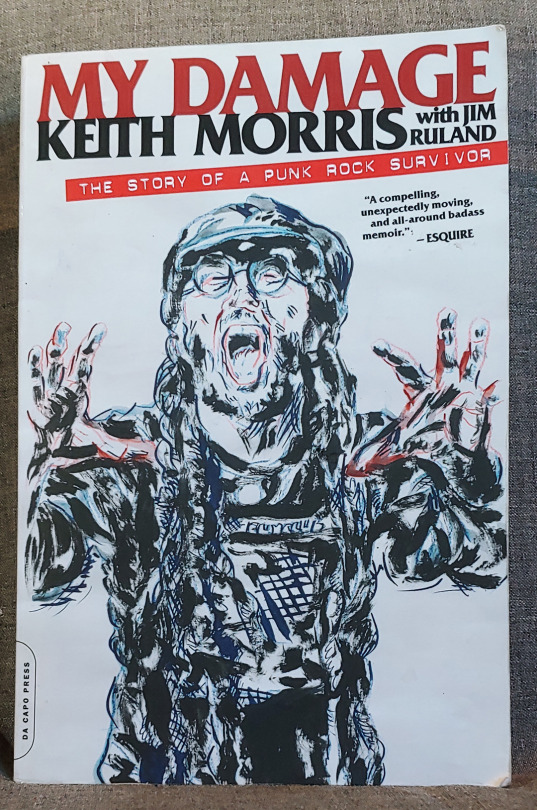

My Damage: The Story of a Punk Rock Survivor -2016 by Keith Morris, Jim Ruland - Blag Flag, Circle Jerks, OFF - Paperback

FOR SALE!!! FIND THIS ITEM AND MORE AT screaming-greek.com

My Damage: The Story of a Punk Rock Survivor

by Keith Morris and Jim Ruland

Used Paperback - First Edition - 310 Pages

Da Capo Press - 2016

Read the full article

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Forest of Fortune by Jim Ruland 2014 Hardcover.

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Read PDF Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST Records EBOOK -- Jim Ruland

Download Or Read PDF Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST Records - Jim Ruland Free Full Pages Online With Audiobook.

[*] Download PDF Visit Here => https://best.kindledeals.club/0306925486

[*] Read PDF Visit Here => https://best.kindledeals.club/0306925486

A no-holds-barred narrative history of the iconic label that brought the world Black Flag, Hüsker Dü, Sonic Youth, Soundgarden, and more, by the co-author of Do What You Want and My Damage. Greg Ginn started SST Records in the sleepy beach town of Hermosa Beach, CA, to supply ham radio enthusiasts with tuners and transmitters. But when Ginn wanted to launch his band, Black Flag, no one was willing to take them on. Determined to bring his music to the masses, Ginn turned SST into a record label. On the back of Black Flag’s relentless touring, guerilla marketing, and refusal to back down, SST became the sound of the underground.In Corporate Rock Sucks, music journalist Jim Ruland relays the unvarnished story of SST Records, from its remarkable rise in notoriety to its infamous downfall. With records by Black Flag, Minutemen, Hüsker Dü, Bad Brains, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, Screaming Trees, Soundgarden, and scores of obscure yet influential bands, SST was the most popular indie

0 notes

Text

The Ledge #533: SST Records (Pt. 2)

Part two of The Ledge's look at SST Records focuses on the second half of the 80's. There are a few big names involved, including Dinosaur Jr., Sonic Youth, Buffalo Tom, and future grunge major label heroes Screaming Trees and Soundgarden. There's a look at the last few Black Flag albums, along with the Greg Ginn solo project Gone. There are also a few veterans of the music scene, including Divine Horsemen, Volcano Suns, and the first solo releases by Husker Du's Grant Hart. Once again, special thanks must go to Jim Ruland for his fabulous book, Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records, which inspired this series of episodes.

I would love it if every listener bought at least one record I played on either of these shows. These great artists deserve to be compensated for their hard work, and every purchase surely helps not only pay their bills but fund their next set of wonderful songs. And if you buy these records directly from the artist or label, please let them know you heard these tunes on The Ledge! Let them know who is giving them promotion! You can find this show at almost any podcast site, including iTunes and Stitcher...or

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE SHOW!

1. Grant Hart, 2541

2. Dinosaur Jr, Little Fury Things

3. Dinosaur Jr, Just Like Heaven

4. Dinosaur Jr., Freak Scene

5. Sonic Youth, Expressway to Yr. Skull

6. Sonic Youth, Bubblegum

7. Sonic Youth, Schizophrenia

8. Black Flag, Can't Decide

9. Black Flag, Slip It In

10. Black Flag, Bastard In Love

11. Black Flag, In My Head

12. Gone, Insidious Distraction

13. Descendents, Coolidge

14. Volcano Suns, Can I Have The Key?

15. Divine Horsemen, Snake Handler

16. Screaming Trees, Transfiguration

17. Screaming Trees, Ivy

18. Screaming Trees, Windows

19. Soundgarden, Flower

20. The Last, So Quick To Say

21. The Last, No Love

22. Das Damen, Reverse Into Tomorrow

23. Angst, Back In January

24. Run Westy Run, Mop It Up

25. Buffalo Tom, Sunflower Suit

26. Grant Hart, Fanfare in D-Major (Come Come)

0 notes

Text

CORPORATE ROCK SUCKS: THE RISE & FALL OF SST RECORDS by Jim Ruland (Hachette Books, 422 pages)

If there was anyone who was up to the task of untangling the messy web that is/has been SST Records it is Jim Ruland. Ruland has been on the punk scene for decades and has more recently written books with Keith Morris (the great My Damage) and a book about Bad Religion (which I’ve yet to read). The history of SST Records has been a long, complicated one with its owner/founder Greg Ginn (guitarist for Black Flag and a million other bands) being accused of not paying artists, taking some to court and generally being completely silent on most issues for the last several years.

It was started in the early 70’s when Ginn was a teenage fan of electronics and from there he started a company building electronic equipment as SST Electronics. Eventually morphing into a record label to first release Black Flag records and then other band’s records. At first the crack team Ginn had assembled at the label (with BF bassist Chuck Dukowski, Dez Cadena, Mugger and many others) had a one-for-all type of mentality with constant police harassment seemingly bonding the group even more. Eventually SST grew into a real label and by the late 80’s it was thee label to be on, releasing classic works by bands like Dinosaur Jr, Sonic Youth, The Minutemen, Meat Puppets, and too many others. Most of these band relationships with Ginn turned sour and some led to court battles. Through a series of interviews with former employees that Ruland did himself as well as ones from previous books/fanzines, Ruland was able to piece together a solid history of the label and all the good and bad that came with it. Over the years I’d heard some of these stories, but not all of them, and Ruland does a great job cobbling them all together into a very engaging, hard-to-put-down format. As Ruland states at the end of the book, Ginn still has time to right the SST ship and make good….but if that ever happens remains to be seen. www.hachettebookgroup.com www.jimruland.net

1 note

·

View note

Text

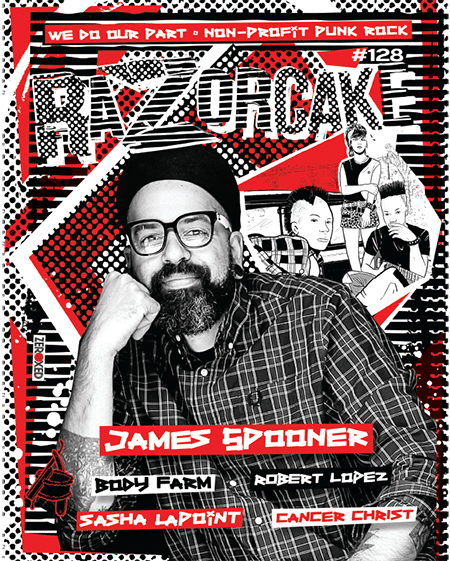

Razorcake 128

Cover by Jesse Zeroxed | Photo by Daryl

FEATURES

James Spooner interview by Daryl and Todd

Robert Lopez (El Vez, The Zeros) interview by David Ensminger

Sasha LaPointe interview by Ryan Nichols

Body Farm interview by Daniel Makagon

Cancer Christ interview by Brandon Oleksy

+

Donna Ramone presents us with One (Specific) Punk’s Guide to Buying a House (That’s a Condo).

Jim Ruland walks with…

View On WordPress

0 notes