#azar gat

Text

2024 Book Review #4 – War in Human Civilization by Azar Gat

This is my first big history book of the year, and one I’ve been rather looking forward to getting to for some time now. Its claimed subject matter – the whole scope of war and violent conflict across the history of humanity – is ambitious enough to be intriguing, and it was cited and recommended by Bret Devereaux, whose writing I’m generally a huge fan of. Of course, he recommended The Bright Ages too, and that was one of my worst reads of last year – apparently something I should have learned my lesson from. This is, bluntly, not a good book – the first half is bad but at least interesting, while the remainder is only really worth reading as a time capsule of early 2000s academic writing and hegemonic politics.

The book purports to be a survey of warfare from the evolution of homo sapiens sapiens through to the (then) present, drawing together studies from several different fields to draw new conclusions and a novel synthesis that none of the authors being drawn from had ever had the context to see – which in retrospect really should have been a big enough collection of dramatically waving red flags to make me put it down then and there. It starts with a lengthy consideration of conflict in humanity’s ‘evolutionary state of nature’ – the long myriads between the evolution of the modern species and the neolithic revolution – which he holds is the environment where the habits, drives and instincts of ‘human nature’ were set and have yet to significantly diverge from. He does this by comparing conflict in other social megafauna (mostly but not entirely primates), archaeology, and analogizing from the anthropological accounts we have of fairly isolated/’untainted’ hunter gatherers in the historical record.

From there, he goes on through the different stages of human development – he takes a bit of pain at one point to disavow believing in ‘stagism’ or modernization theory, but then he discusses things entirely in terms of ‘relative time’ and makes the idea that Haida in 17th century PNW North America are pretty much comparable to pre-agriculture inhabitants of Mesopotamia, so I’m not entirely sure what he’s actually trying to disavow – and how warfare evolved in each. His central thesis is that the fundamental causes of war are essentially the same as they were for hunter-gatherer bands on the savanna, only appearing to have changed because of how they have been warped and filtered by cultural and technological evolution. This is followed with a lengthy discussion of the 19th and 20th centuries that mostly boils down to trying to defend that contention and to argue that, contrary to what the world wars would have you believe, modernity is in fact significantly more peaceful than any epoch to precede it. The book then concludes with a discussion of terrorism and WMDs that mostly serves to remind you it was written right after 9/11.

So, lets start with the good. The book’s discussion of rates of violence in the random grab-bag of premodern societies used as case studies and the archaeological evidence gathered makes a very convincing case that murder and war are hardly specific ills of civilization, and that per capita feuds and raids in non-state societies were as- or more- deadly than interstate warfare averaged out over similar periods of time (though Gat gets clumsy and takes the point rather too far at times). The description of different systems of warfare that ten to reoccur across history in similar social and technological conditions is likewise very interesting and analytically useful, even if you’re skeptical of his causal explanations for why.

If you’re interested in academic inside baseball, a fairly large chunk of the book is also just shadowboxing against unnamed interlocutors and advancing bold positions like ‘engaging in warfare can absolutely be a rational choice that does you and yours significant good, for example Genghis Khan-’, an argument which there are apparently people on the other side of.

Of course all that value requires taking Gat at his word, which leads to the book’s largest and most overwhelming problem – he’s sloppy. Reading through the book, you notice all manner of little incidental facts he’s gotten wrong or oversimplified to the point where it’s basically the same thing – my favourites are listing early modern Poland as a coherent national state, and characterizing US interventions in early 20th century Central America as attempts to impose democracy. To a degree, this is probably inevitable in a book with such a massive subject matter, but the number I (a total amateur with an undergraduate education) noticed on a casual read - and more damningly the fact that every one of them made things easier or simpler for him to fit within his thesis - means that I really can’t be sure how much to trust anything he writes.

I mentioned above that I got this off a recommendation from Bret Devereaux’s blog. Specifically, I got it from his series on the ‘Fremen Mirage’ – his term for the enduring cultural trope about the military supremacy of hard, deprived and abusive societies. Which honestly makes it really funny that this entire book indulges in that very same trope continuously. There are whole chapters devoted to thesis that ‘primitive’ and ‘barbarian’ societies possess superior military ferocity and fighting spirit to more civilized and ‘domesticated’ ones, and how this is one of the great engines of history up to the turn of the modern age. It’s not even argued for, really, just taken as a given and then used to expand on his general theories.

Speaking of – it is absolutely core to the book’s thesis that war (and interpersonal violence generally) are driven by (fundamentally) either material or reproductive concerns. ‘Reproductive’ here meaning ‘allowing men to secure access to women’, with an accompanying chapter-length aside about how war is a (possibly the most) fundamentally male activity, and any female contributions to it across the span of history are so marginal as to not require explanation or analysis in his comprehensive survey. Women thus appear purely as objects – things to be fought over and fucked – with the closest to any individual or collective agency on their part shown is a consideration that maybe the sexual revolution made western society less violent because it gave young men a way to get laid besides marriage or rape.

Speaking of – as the book moves forward in time, it goes from being deeply flawed but interesting to just, total dreck (though this also might just me being a bit more familiar with what Gat’s talking about in these sections). Given the Orientalism that just about suffuses the book it’s not, exactly, surprising that Gat takes so much more care to characterize the Soviet Union as especially brutal and inhumane that he does Nazi Germany but it is, at least, interesting. And even the section of World War 2 is more worthwhile than the chapters on decolonization and democratic peace theory that follow it.

Fundamentally this is just a book better consumed secondhand, I think – there are some interesting points, but they do not come anywhere near justifying slogging through the whole thing.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let us start with face-to-face confrontations. Feuds by individuals, often aided by kin, were very frequent, resulting from reasons that have already been discussed, mostly relating to women. Both sides were armed, and strong words were often followed by blows with clubs and by spear throwing. However, both sides were held back by their kin and friends and prevented from getting to grips with or seriously hurting each other. In fact:

The contestants usually depend upon this, and talk much ‘harder’ (dal ) to each other than they would if they knew they were going to be allowed to have a free play at each other. … They are able, by remonstrating with their friends and struggling to get free from them, to vent their outraged emotions and prove to the community that no one can impinge upon their rights without a valiant effort being made to prevent this from happening. Obviously there is a certain amount of bluff in the conduct of the contestants on some occasions … few killings ever result.

"War in Human Civilization", Azar Gat, quoting "Murgngin Warefare", Lloyd Warner

comically similar to the classic bar fight tactic where you struggle against your friends holding you back to prove that youre serious. the game theory of conflict hasnt changed in 10000 years

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

6 for the book ask game - i feel like there must be a fair few

6. Was there anything you meant to read, but never got to?

maybe a couple.

Most gallingly Cyteen by C. J. Cherryh (sitting on my table for literally more than a year), War in Human Civilization by Azar Gat (paid to get special ordered by book store) and He Who Drowns the World by Shelly Parker-Chan (pre-ordered and picked up by not started)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Quando Éramos Mentirosos"

Sɪɴᴏᴘsᴇ Oғɪᴄɪᴀʟ: A família Sinclair parece perfeita. Ninguém falha, levanta a voz ou cai no ridículo. Os Sinclair são atléticos, atraentes e felizes. A sua fortuna é antiga. Os seus verões são passados numa ilha privada, onde se reúnem todos os anos sem exceção. É sob o encantamento da ilha que Cadence, a mais jovem herdeira da fortuna familiar, comete um erro: apaixona-se desesperadamente.

Cadence é brilhante, mas secretamente frágil e atormentada. Gat é determinado, mas abertamente impetuoso e inconveniente. A relação de ambos põe em causa as rígidas normas do clã. E isso simplesmente não pode acontecer. Os Sinclair parecem ter tudo. E têm, de facto. Têm segredos. Escondem tragédias. Vivem mentiras. E a maior de todas as mentiras é tão intolerável que não pode ser revelada. Nem mesmo a si.

Aᴜᴛᴏʀᴀ: E. Lockhart

-------------------------------------------------------

ALERTA SPOILERS!

-------------------------------------------------------

O Mᴇᴜ Rᴇsᴜᴍᴏ: "Quando Éramos Mentirosos" segue a vida de Cadence Sinclair, de quase 18 anos, revelando de forma dividida o seu presente e o seu passado, alternando sucessivamente entre os dois e visões um tanto irrealistas que a protagonista insiste em ter. Logo nas primeiras páginas são-nos dadas a conhecer as pessoas mais importantes da vida de Cadence: o seu pai, que mais pela absência do que pela presença se vincula no espírito da filha, Johnny, o primo extrovertido e disparatado que sempre fez parte da sua vida, Mirren, a prima docemente complicada que lhe enche o coração, e por fim Gat, um "forasteiro" que por sorte ou azar se infiltrou na família e que imprimiu uma marca irreversível em Cadence. Cedo na história, a autora alude a um "acidente" misterioso de que a protagonista não se lembra vividamente e que lhe causou danos profundos, não só a nível cerebral mas também à disposição, substituindo-lhe as madeixas cor de ouro, o sorriso aberto e o espírito traquina por uma cabeleira preta, uma boca melancólica e um vazio no seu coração. É rapidamente estabelecido que Cadence depende de medicação, algo que não orgulha os Sinclairs, uma família que só é perfeita se se olhar de longe e que usa a elegância, as ilhas e as mansões para esconder os "cadáveres" que lhes mancham a imagem. O evento enigmático torna-se então o tema central da história, que continua a recuar e a avançar no tempo, enquanto Cadence volta, no presente, à ilha em que todos os verões a sua vida realmente acontecia, e da qual esteve absente por alguns anos. Lá reúne-se com a família, que se comporta de maneira mais bizarra do que o habitual, e com o trio que lhe é tão querido, que se mostra fraco e insiste em afastar-se dos dramas adultos. Aí, o romance com Gat desenvolve-se e com a paixão vêm problemas há muito enterrados na sua consciência. Esforçando-se ao máximo por recuperar o estado feliz que a caracterizava e as memórias do que foi o tal acidente, algo que todos se recusam a revelar, Cadence caminha em direção ao clímax do livro, onde uma revelação obscura e profundamente traumatizante a espera, não a deixando escapar à destruição do frágil castelo de cartas que constitui o que ela sabe.

Cʀɪᴛᴇ́ʀɪᴏs ᴅᴇ Cʟᴀssɪғɪᴄᴀᴄ̧ᴀ̃ᴏ:

Qᴜᴀʟɪᴅᴀᴅᴇ ᴅᴀ Pʀᴏsᴀ: Absolutamente linda! Pode não ser o estilo de todos mas eu pessoalmente adoro uma escrita floreada que não passe o limite da beleza para a palha, e este livro cumpre nisso. O estilo da autora é super visual, e algo perturbador quando as cenas são dramáticas, o que só prova a força da forma como ela executa as linhas.

Hɪsᴛᴏ́ʀɪᴀ: Eu achei a história em si ótima, agora, houve muitas coisas que não ficaram esclarecidas e isso para muitos pode significar um livro mal planeado ou negligência da autora. Eu tendo a inclinar-me para o lado oposto, acho que foi totalmente propositado não conseguirmos distinguir a realidade da imaginação da Cadence e ficarmos a perguntarmo-nos se existem fenómenos sobrenaturais ou se é ela a alucinar. Até porque o livro tem um seguimento, ou uma prequela no caso, que supostamente esclarece muitas das questões.

Pᴇʀsᴏɴᴀɢᴇɴs: Eu adorei todas as personagens (tirando as que é suposto nós odiarmos). Parecem todas ter os seus propósitos, as suas motivações e vidas fora do que se passa com a protagonista. A maior parte disto é encoberto, não é suposto a Cadence conhecer o que se passa à sua volta, isso é muito intencional, mas de cada vez que a Mirren, o Johnny, e especialmente o Gat, entraram em cena, eu fiquei entusiasmada com o que poderia acontecer.

Rᴏᴍᴀɴᴄᴇ: A relação de Gat e Cadence é definitivamente um foco da história, especialmente por causa da grande revelação, que gira muito à volta da intensidade dos sentimentos que eles têm um pelo outro. Esta é explorada, claro, mas na grossura do livro, acaba por não ocupar tanto espaço como eu pessoalmente gostaria, deixa algo mais a desejar e muitas questões relativamente a quanto do que se passava com eles era real.

Iᴍᴇʀsᴀ̃ᴏ: Devido principalmente ao estilo de prosa da escritora, é muito fácil entrarmos no mundo que nos é descrito, ficamos realmente envolvidos no que se passa e eu nunca tive de fazer um esforço para imaginar o que me estava a ser dito.

Iᴍᴘᴀᴄᴛᴏ: Não vou mentir, depois do fim fiquei 1 hora a olhar para o livro a sentir-me perdida, e um bocadinho parva, porque era impossível aquilo ter acabado como acabou, por isso devia-me ter escapado algo. Não, não escapou. Quando percebi isso, fiquei cerca de 3 dias presa numa espécie de melancolia pós-história, porque o livro me tinha agarrado com tamanha força que não sabia o que fazer com a sua conclusão, e que conclusão! Depois de isso passar e ter começado outros livros, o impacto deste foi-se suavizando e agora, olhando para trás, não me parece que tenha sido um daqueles livros que nos mudam para sempre, só um daqueles em que o autor é esperto o suficiente para nos deixar perturbados tempo que chegue para o divulgarmos.

Cʟᴀssɪғɪᴄᴀᴄ̧ᴀ̃ᴏ Fɪɴᴀʟ: ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Iᴅᴀᴅᴇ Aᴄᴏɴsᴇʟʜᴀᴅᴀ: Pelo menos 16 anos, a história toca em alguns temas sensíveis e tem descrições floreadas que são um tanto fortes, não é de todo um livro para todos apesar de existirem por aí uns imensamente mais perturbadores.

Cᴏɴᴄʟᴜsᴀ̃ᴏ/Oᴘɪɴɪᴀ̃ᴏ Fɪɴᴀʟ: Geralmente, como deu para ver, foi um livro que eu apreciei bastante, não é algo tão dramático como isso para gente que já tenha lido, por exemplo, certos clássicos, mas para quem só lê coisas ligeiras, esta obra choca um pouco. Depois disto tudo posso dizer, RECOMENDO ESTE LIVRO!

Pᴀʀᴀ ᴏʙᴛᴇʀ: Quando Éramos Mentirosos, E. Lockhart - Livro - Bertrand

Assɪɴᴀᴅᴏ: Ƹ̵̡Ӝ̵̨̄Ʒ 𝐿𝓊𝓏 Ƹ̵̡Ӝ̵̨̄Ʒ

#críticas literárias#book reviews#book recommendations#book recs#e. lockhart#we were liars#livros#leitores#bookblr#books & libraries#bookworm#ya fiction#português#portugal#brasil

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

cloudy day: lots of boldo tea -> pass out at 07:30 -> wake up at 8 and hydrate -> read Azar Gat on medieval European proto-nationalism -> pure black coffee - > (stretching) range of motion -> I went to the ATM and now I'm posting this shit to say that routine is cuckold stuff

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the manner of a commonplace book, here are some things I've learned over the past decade-ish that I think are very, very, very important.

A lot of reactionaries' behavior is explained by them being marks for an interlocking network of cons, among which the ideological cons and the money cons are a continuous gradient; there is no discrete separating barrier between the ideology grift and the wallet-plundering grift. The American reactionary movement's psychosis of the 21st century is anything but unprecedented — they believed plenty of unhinged and evil things before this era! The change in the 21st century is mostly a change in leadership: as Alex Pareene explains, "Republicans realized they’d radicalized their base to a point where nothing they did in power could satisfy their most fervent constituents. Then — in a much more consequential development — a large portion of the Republican Congressional caucus became people who themselves consume garbage conservative media, and nothing else. That, broadly, explains the dysfunction […] Congressional Republicans went from people who were able to turn their bullshit-hose on their constituents, in order to rile them up, to people who pointed it directly at themselves, mouths open." How did that happen? They did it to themselves.

On the question of "has war changed?", Fallout is wrong and Metal Gear Solid is right: war has changed, even before you account for nuclear weapons. Per Azar Gat, war used to pretty uniformly be very good for the winners. At some point before 1917, that stopped being true, and instead wars between peers default to being disastrously bad for all belligerents. The industrial revolution meant that not only was "just build more stuff" for the first time as lucrative as war, but also the exact same stuff that the most powerful nations were building (it turns out that the requirements for building a good 1800s steam engine overlap heavily with the requirements for building a good 1800s artillery piece) makes war more destructive and thus a worse deal even for a war's winners. The consequences of this change are still actively happening, and the lessons of it are being unevenly learned.

Changing people's minds about stuff is preposterously difficult. Some of this difficulty is inherent, but some of it is self-inflicted, so I am here to warn you of one of those things that's crushingly obvious once you've internalized it but also feels too trivial to matter if you haven't: other people often have values and beliefs that are meaningfully different from yours, and even if they express themselves clumsily (or outright deceptively), things will go poorly for you if you assume that they share your beliefs & values but are just stupid/mistaken/petulant. Beware of explanations based on hypocrisy: it's overwhelmingly more common that what you consider hypocritical, they think is completely fine, it's just their rationale for thinking so is a value or principle that you reject. Calling them hypocrites in that situation will not change their values. You might have a shot at getting people out of shit beliefs by asking them "How, EXACTLY AND IN DETAIL, does that work?" but to credibly ask that question at all, you have to be in a position where they don't dismiss you, which is already a challenge. On the bright side, changing people's minds by direct interpersonal persuasion isn't as necessary for a better world as one might think. A large proportion of the evil in the world comes from the tendency towards authoritarianism all humans have in greater or lesser degree, and while high-authoritarianism folks are the most predisposed to participate in evil, they're also the most conformist: if you change the material arrangements of power, they will swiftly change to accommodate the new arrangements, because they're fundamentally conformist, fearful, and desperate to obey authority figures that they perceive to be legitimate (that's what it means to be high in authoritarianism).

"What is a disability?" is a question more similar to "what's the correct side of the road to drive on?" than it is to "how many peptides are in this protein?" It's not about whether someone needs a wheelchair or cane or hearing aid, it's about which needs are collectively regarded as real needs whose satisfaction should be built into the infrastructure of society versus which needs are regarded as "you're on your own, lol good luck." You are fragile and made of meat. Your abilities will eventually degrade. It benefits everyone for the answer to "which needs should we infrastructurally, systematically meet?" to be as expansive as possible.

Your sense of urgency is one of the easiest ways to manipulate you, and is one of the handles that people who want to extract something from you reach for first. It is critically important to cultivate a personal, internal ability to judge "does this matter? does this matter to me? does this matter in a time-sensitive way?" Personally I find it helpful to start with "what happens if I do deadass nothing?" but different people find different things helpful here. The important part is that when you accept someone else's judgment about "is this urgent or not?", that should be something you actively choose, not something you gloss over, not a free ride for them.

The flip side of "it's incredibly hard to persuade people" is that there are probably a lot of things where you have significant hang-ups about others' opinions and they simply do not care. Simply can't be arsed at all. They have plenty of their own shit to deal with and, often as not, your anxieties are completely invisible to them. A life lived in fear of the judgment of the abstract unspecified omnipresent other is a life lived in a horrid prison. Go do pleasant things, things you enjoy, things that are good for your heart. If there is such a cruel judgment as you fear, let them at least work for it, rather than allowing its cruelty to ziptie you preëmptively.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@corsetlungs said : also, any YA books the admins and fellow members would like to see characters from? ♡

our members and my fellow admins would love to see maggie and adam from along for the ride !! , anyone from someone like you + just listen + once & for all by sarah dessen , gat from we were liars , jonny & miranda from life as we knew it , cooper clay & nate macauley & browyn rojas & addy prentiss from one of us is lying , prince henry & princess bea & june claremont-diaz & nora holleran & pez from red white and royal blue , anyone from gregor the overlander, harrow, ianthe, john, abigail, magnus, camilla, palamedes, coronabeth, dulcinea from the locked tomb series, anyone from if we were villains, the raven cycle, or shadowhunters series, sydney sage, adrien ivashkov, dimitri belikov from vampire academy, mare barrow, maven calore, cal calore from red queen, the remaining cullens and denalis, laurent, anne sutherland, riley biers, aro, caius, marcus from twilight, america singer, maxon schreave from the selection, ari azar, gwen, lam, merlin, kay, jordan, arthur, and val from once and future !! sorry that’s a bit of a long list, but anyone would be loved!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quais são as principais estratégias de apostas utilizadas pelos apostadores da Mladost Gat para aumentar suas chances de ganhar?

🎰🎲✨ Receba 2.000 reais e 200 rodadas grátis, além de um bônus instantâneo para jogar jogos de cassino com apenas um clique! ✨🎲🎰

Quais são as principais estratégias de apostas utilizadas pelos apostadores da Mladost Gat para aumentar suas chances de ganhar?

Análise estatística de jogos

A análise estatística de jogos é uma ferramenta poderosa utilizada por equipes esportivas, treinadores, analistas e até mesmo pelos próprios jogadores para entender melhor o desempenho em campo e identificar áreas de melhoria. Essa prática envolve a coleta, organização e interpretação de dados relacionados ao jogo, como posse de bola, chutes a gol, passes certos, entre outros.

Uma das principais vantagens da análise estatística de jogos é a capacidade de fornecer insights objetivos e baseados em evidências sobre o desempenho de uma equipe ou jogador. Ao invés de depender apenas de impressões subjetivas, os dados estatísticos permitem uma avaliação mais precisa e imparcial.

Além disso, a análise estatística de jogos também pode ajudar na tomada de decisões estratégicas. Ao identificar padrões e tendências nos dados, os treinadores podem ajustar suas táticas durante uma partida ou desenvolver estratégias de longo prazo para enfrentar adversários específicos.

Outro aspecto importante da análise estatística de jogos é a capacidade de monitorar o progresso ao longo do tempo. Ao acompanhar métricas-chave em diferentes jogos e períodos da temporada, é possível avaliar o impacto de mudanças táticas, ajustes na escalação e até mesmo o desenvolvimento individual dos jogadores.

No entanto, é importante ressaltar que a análise estatística de jogos deve ser usada como uma ferramenta complementar, e não como a única base para avaliação. O contexto do jogo, as condições de campo, o estilo de jogo do adversário e outros fatores também devem ser considerados para uma análise completa e precisa.

Em resumo, a análise estatística de jogos desempenha um papel fundamental no mundo do esporte, fornecendo insights valiosos, apoiando a tomada de decisões estratégicas e acompanhando o progresso ao longo do tempo. Quando usada de maneira adequada, essa prática pode ser uma ferramenta poderosa para melhorar o desempenho e alcançar o sucesso no campo.

Gestão de banca eficaz

A gestão de banca eficaz é um aspecto fundamental para qualquer pessoa que esteja envolvida em atividades financeiras, especialmente no contexto de investimentos e apostas. Trata-se do processo de gerenciamento cuidadoso dos recursos financeiros disponíveis, com o objetivo de maximizar os lucros e minimizar as perdas ao longo do tempo.

Para os investidores, a gestão de banca eficaz implica em diversificar os investimentos, distribuindo os recursos entre diferentes classes de ativos e estratégias de investimento. Isso reduz o risco de perda total em caso de desempenho ruim de um único investimento ou setor.

No contexto das apostas esportivas ou jogos de azar, a gestão de banca eficaz é ainda mais crucial. Isso envolve estabelecer um plano claro de quanto dinheiro será apostado em cada evento ou jogo, levando em consideração a probabilidade de ganho e o tamanho do bankroll disponível. Um dos princípios fundamentais da gestão de banca é evitar apostas excessivamente arriscadas que possam levar a perdas significativas e, em vez disso, adotar uma abordagem mais conservadora e disciplinada.

Além disso, a gestão de banca eficaz também envolve a definição de metas realistas de lucro e a implementação de estratégias para proteger os ganhos obtidos. Isso pode incluir retirar parte dos lucros regularmente e reinvestir apenas uma porcentagem dos ganhos para manter o crescimento sustentável do bankroll.

Em resumo, a gestão de banca eficaz é essencial para garantir a estabilidade financeira e o sucesso a longo prazo em qualquer empreendimento que envolva o uso de dinheiro. Ao adotar uma abordagem disciplinada e cuidadosa para gerenciar os recursos financeiros disponíveis, os indivíduos podem aumentar suas chances de alcançar seus objetivos financeiros e evitar armadilhas comuns que levam à perda de capital.

Utilização de modelos matemáticos

Os modelos matemáticos desempenham um papel crucial em diversas áreas do conhecimento, desde a física e a engenharia até a economia e a biologia. Essas ferramentas permitem aos pesquisadores e profissionais entenderem e preverem fenômenos complexos por meio de equações e algoritmos.

Um dos principais benefícios da utilização de modelos matemáticos é a capacidade de simular situações que podem ser difíceis ou impossíveis de reproduzir na vida real. Por exemplo, na área da física, os cientistas podem usar modelos matemáticos para entender o comportamento de partículas subatômicas ou prever a trajetória de um objeto em movimento.

Na engenharia, os modelos matemáticos são fundamentais para o projeto e otimização de sistemas complexos, como pontes, aviões e redes de comunicação. Eles permitem aos engenheiros testar diferentes cenários e identificar a melhor solução para um determinado problema.

Na economia, os modelos matemáticos são usados para entender o comportamento dos mercados financeiros, prever tendências econômicas e desenvolver políticas públicas. Eles ajudam os economistas a analisar dados e tomar decisões informadas sobre questões como inflação, desemprego e crescimento econômico.

Além disso, os modelos matemáticos também são amplamente utilizados em áreas como a biologia, a medicina e a meteorologia. Eles ajudam os cientistas a entenderem os padrões de crescimento de organismos, preverem a propagação de doenças e modelarem o clima da Terra.

Em resumo, os modelos matemáticos são ferramentas poderosas que desempenham um papel fundamental em nossa compreensão do mundo ao nosso redor e nos ajudam a tomar decisões informadas em uma ampla variedade de áreas.

Apostas ao vivo com base em insights

As apostas ao vivo têm se tornado cada vez mais populares entre os entusiastas do jogo online. Com a tecnologia avançada e a disponibilidade de dados em tempo real, os apostadores agora têm a oportunidade de fazer suas apostas com base em insights atualizados durante o decorrer do evento esportivo.

Uma das vantagens das apostas ao vivo com base em insights é a capacidade de adaptar-se rapidamente às mudanças que ocorrem durante o jogo. Por exemplo, se um jogador-chave se machuca durante uma partida de futebol, isso pode afetar significativamente o desempenho da equipe. Com acesso a essas informações em tempo real, os apostadores podem ajustar suas estratégias e fazer novas previsões com base nesses eventos inesperados.

Além disso, as apostas ao vivo com base em insights permitem que os apostadores identifiquem tendências emergentes e padrões de jogo que podem não ser evidentes antes do início da partida. Isso pode incluir o desempenho de um jogador específico, a eficácia de uma estratégia de jogo ou até mesmo as condições climáticas que podem afetar o resultado do evento esportivo.

No entanto, é importante notar que as apostas ao vivo com base em insights também apresentam desafios únicos. Os apostadores precisam ser rápidos para tomar decisões e podem enfrentar uma maior volatilidade nas probabilidades à medida que o jogo se desenrola.

Em resumo, as apostas ao vivo com base em insights oferecem uma emocionante oportunidade para os apostadores aproveitarem informações em tempo real e ajustarem suas estratégias conforme o jogo se desenrola. Com acesso a dados atualizados e uma compreensão profunda do esporte em questão, os apostadores podem aumentar suas chances de sucesso e desfrutar de uma experiência de apostas mais envolvente e dinâmica.

Estratégias de handicap e spread

Estratégias de handicap e spread são conceitos comumente utilizados em diversos tipos de apostas esportivas, especialmente em jogos onde há uma grande discrepância de habilidade entre os competidores. Essas estratégias visam nivelar o campo de jogo, oferecendo vantagens ou desvantagens artificiais a uma das equipes ou jogadores envolvidos.

No handicap, uma das equipes é considerada favorita e começa o jogo com uma pontuação fictícia negativa, enquanto a equipe considerada menos favorita começa com uma pontuação positiva. Isso significa que, para a equipe favorita vencer a aposta, ela precisa superar não apenas o adversário, mas também a diferença imposta pelo handicap. Por outro lado, a equipe menos favorita pode vencer a aposta mesmo perdendo o jogo, desde que consiga manter a diferença abaixo do handicap.

Já o spread funciona de forma semelhante, mas é mais comumente utilizado em apostas esportivas como basquete e futebol americano. Nesse caso, em vez de uma pontuação fixa, é estabelecida uma margem de pontos pela qual uma equipe precisa vencer para que a aposta seja considerada vencedora. Por exemplo, se uma equipe tem um spread de -3 pontos, ela precisa vencer o jogo por uma margem de pelo menos quatro pontos para cobrir o spread.

Ambas as estratégias podem ser utilizadas pelos apostadores para aumentar suas chances de sucesso, especialmente em situações onde há um claro favorito e azarão. No entanto, é importante compreender bem as nuances de cada estratégia e analisar cuidadosamente as estatísticas e o desempenho das equipes envolvidas antes de fazer uma aposta.

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

The Reaction Against the End of History

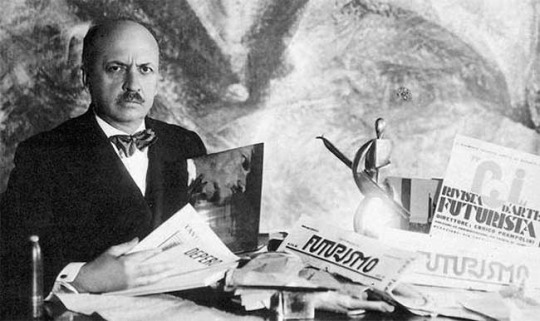

Recently reading Azar Gat’s Fascist and Liberal Visions of War: Fuller, Liddell Hart, Douhet, and other Modernists I happened upon his characterization of a “fascist minimum,” which is something like C. S. Lewis’ attempt to define “mere Christianity.” So here is Gat’s mere fascism:

“Fascism emerged on the heels of industrialization, urbanization, and the growth of mass society. Those who shared in the proto-fascist and fascist ‘mood’ rebelled against bourgeois culture, with its ‘decadent’ materialism, commercialism, atomistic and alienating individualism, and liberal-humanitarian values. They dreaded the further advance of plebeianism, mediocrity, and triviality expected with growing democratization. Espousing idealism and exalting youth, elementary dynamism, and vitalism, they called for comprehensive spiritual and cultural rejuvenation and the creation of a new man within radically reconstructed society. They sought to overcome divisive parliametarianism, capitalism, and socialism through the application of communal solution which would mobilize the energies and loyalty of the masses around unifying natural traditions, myths, and ideals. At the same time, they held that government should firmly remain in the hands of a worthy élite, the creator and leader of the New Order.” (Azar Gat, Fascist and Liberal Visions of War: Fuller, Liddell Hart, Douhet, and other Modernists, Oxford: Clarendon, 1998, p. 4)

As soon as I read this I immediately thought of the final paragraph of Francis Fukuyama’s 1989 essay “The End of History?” (1989):

“The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands. In the post-historical period there will be neither art nor philosophy, just the perpetual caretaking of the museum of human history. I can feel in myself, and see in others around me, a powerful nostalgia for the time when history existed. Such nostalgia, in fact, will continue to fuel competition and conflict even in the post-historical world for some time to come. Even though I recognize its inevitability, I have the most ambivalent feelings for the civilization that has been created in Europe since 1945, with its north Atlantic and Asian offshoots. Perhaps this very prospect of centuries of boredom at the end of history will serve to get history started once again.” (Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” The National Interest, Summer 1989)

An enormous commentary rapidly grew up around Fukuyama’s essay, and also around what may be considered its companion piece, Samuel P. Huntington’s “The Clash of Civilizations?” (1993). These two essays—both subsequently turned into books—defined grand strategy discussions during the 1990s, and they continue to echo today. As I have discussed both of these essays in other blog posts, I don’t want to do that at present. The question that interests me at present is why Azar Gat’s definition of a minimal fascism immediately brought to my mind Fukuyama’s sketch of the end of the history.

The connection between these two passages is the properties ascribed to a society seen, from the one perspective, as the end point of social development, while, seen from another perspective, is the point of origin for a reactionary social development. What Fukuyama described as the end of history, the end of the ideological conflict that had been making history, is what Gat described as the conditions of discontent prior to the appearance of a new ideology explicitly opposed to the values of the reigning liberal order.

So while Fukuyama in this original essay (he has published numerous clarifications and elaborations since then) speculates that boredom may eventually bring about the end of history, Gat’s understanding of a fascist minimum is that it is not boredom, but contempt and disgust that eventually allows for the transcendence of the end of history. What for Fukuyama is an end point for civilization, is for Gat’s fascist minimum a point of departure. All of the conditions that Fukuyama describes are the conditions that Gat identifies as the raison d’être for fascism.

For Fukuyama, the end of history is the culmination of the liberal world order, the end point of possible development for liberalism—liberalism triumphant and unchallenged by any alternative ideology. And this explains a lot. Liberalism in power becomes aesthetically and morally repellent—smug, self-satisfied, lazy, undisciplined, permissive, indulgent, and, ultimately, self-destructive—to the point that it provokes a rebellion not out of boredom, but out of disgust. However, it is entirely possible that reactionaries follow a trajectory of becoming bored first, before formulating a reaction to the society that they found to be mind-numbingly banal, so Fukuyama may be right about the role of boredom, except that social evolution does not end with this boredom.

In the political cycles that have characterized western civilization, we often find the fascist right appears initially as an aesthetic movement, as it is the artists who are among the first to feel the corruption of liberalism. For example, in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s “Manifesto of Futurism” (1909) we find many of themes of the “fascist minimum” given explicit expression long before fascism as a political movement gained ground in Italy.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

50 more pages into War in Human Civilization and deeply deeply irked with - well, the five page op-ed about women serving in combat roles thrown in the middle of a discussion of hunter-gatherers, certainly, but also specifically if you're going to say something like 'across nature males in social species are more aggressive and violent than females' someone should throw a hyena pup at you with great force and vigor.

#also made a broad reference to 'alpha' hierarchies in wolf packs and didn't even provide a citation#deeply unserious#war in human civilization#azar gat#tht

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

that ‘Inuit parents never yell at their children and raise them to have remarkable self control’ article is making the rounds again, and reminds me that I never know how to read ‘pop anthropology reporting cultural practices very different from mine’ articles because

My suspicion is that the average anthropologist/journalist is prone to projecting or exaggerating or straight up lying for motivations like ‘getting clicks’ and ‘inventing a counternarrative about human nature in order to push their pet theory (in their home society where they’re publishing) about how societies work or should work’

But human cultures are genuinely very diverse and you should expect to be run into a ton of real stuff from other cultures that blow your mind / make you suspect it’s fake

And the only way to satisfactorily verify whether a pop anthro article has accurately represented some very different culture is to deep dive existing literature and cross-reference descriptions of that culture from multiple sources (if they exist), or go talk to the people the article is about yourself.

So the net effect is that I read articles and think “that would be cool if true. no way to tell, though. I’m going to try to pretend I didn’t read that”. Given that I should probably just reading them altogether

#rambl#i distrust that inuit pop anthro article in particular because azar gat's book on war specifically mentions inuits –#as an example of a#representative hunter gatherer culture with representative staggering homicide rates#not that you can't kill people in a very self controlled nonshouty way. would love to go that way myself

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

my ideas these days are not really radical ones. i am thinking about it like this: i am in the same stage that Engels was in when he took up military theory and wrote military analysis for newspapers for money (usually under Marx’s name). Azar Gat makes this point; at this stage Engels did not develop any kind of ‘materialist’ version of military theory or apply their peculiar theory of history to military history and wouldn’t until anti-Durhing. i am applying myself to the discipline of philology in the normal way as best i can, and the little things i write presently are not based on anything but these facts of the discipline which a beginner might learn or the simple facility for argument that i have developed in doing so. i know very well that its all resting on sand, yet there will be time to make my own sand-castles later on. in my defense i no longer think anything i said before was radical either, only ever resentful or put forcefully.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

With A Martyr Complex: Reading List 2021

Adapted from the annual list from @balioc, a list of books (primarily audiobooks) consumed this year. This list excludes several podcasts, but includes dramatizations and college lecture series from The Great Courses, which I consume like a disgusting fiend.

Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 by Tony Judt

Utopia by Thomas More

The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran

The Protestant Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism by Max Weber (tl: Talcott Parsons)

1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed by Eric H. Cline

Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character by Jonathan Shay

Understanding the Dark Side of Human Nature by Daniel Breyer

On China by Henry Kissinger

The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race by Walter Isaacson

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell

Iliad by Homer (tl: W. H. D. Rouse)

The Iliad of Homer by Elizabeth Vandiver

The City of Brass by S. A. Chakraborty

The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli

Machiavelli in Context by William R. Cook

Death in Florence: The Medici, Savonarola and the Battle for the Soul of the Renaissance City by Paul Strathern

The Borgias: The Hidden History by G. J. Meyer

Rise and Fall of The Borgias by William Landon

The Borgias and Their Enemies by Christopher Hibbert

War and World History by Jonathan P. Roth

The Medici by Paul Strathern

Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino

The Art of War by Niccolo Machiavelli

The Venetians by Paul Strathern

Wyrms by Orson Scott Card

Perhaps The Starsby Ada Palmer

Odyssey by Homer (tl: W. H. D. Rouse)

The Odyssey of Homer by Elizabeth Vandiver

The Lost Books of The Odyssey by Zachary Vance

A History of India by Michael H. Fisher

How to Achieve Financial Independence and Retire Early by JD Roth

Gilgamesh: A New English Version by Sin-Leqi-Unninni (standard ancient version), Stephen Mitchell (adaptor)

Candide: or, The Optimist-Voltaire

The Artist, The Philosopher, and The Warrior: Da Vinci, Machiavelli, and Borgia and the World They Shaped by Paul Strathern

Zadig; or, The Book of Fate by Voltaire

Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue by Marquis de Sade (tl: John Phillips)

America’s Founding Women by Cassandra Good

Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals by Immanuel Kant

Incomplete books: War in Human Civilization by Azar Gat, Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy, The Enlightenment-The Pursuit of Happiness, 1680-1790 by Ritchie Robertson, and Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes.

---

Great Courses consumed: 8

Non-Great Courses Nonfiction consumed: 16

---

Works consumed by women: 5

Works consumed by men: 33

Works consumed by men and women: 0

Works that can plausibly be considered of real relevance to foreign policy (including appropriate histories): 6

---

With A Martyr Complex’s Choice Award, fiction division: Invisible Cities

>>>> Honorable mention: Perhaps the Stars, Wyrms

With A Martyr Complex’s Choice Award, nonfiction division: Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945

>>>> Honorable mention: The Borgias: The Hidden History, The Iliad of Homer, Death in Florence: The Medici, Savonarola, and the Battle for the Soul of the Renaissance City, The Odyssey of Homer

>>>> Great Courses Division: Understanding the Dark Side of Human Nature

The Annual “An Essential Work of Surpassing Beauty that Isn’t Fair to Compare To Everything Else” Award: The Prince

>>>> Honorable mention: Iliad (it would have beaten The Prince in a better translation), Down and Out in Paris and London, Zadig; or, The Book of Fate, The Protestant Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism

The “Reading This Book Will Give You Great Insight Into The Way I See The World” Award: Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character

>>>> Honorable mention: War and World History

The “Reading This Book Was Nightmarishly Awful but also Deeply Rewarding in Ways I Did Not Anticipate such that I Cannot Tell if I Recommend It or Not” Award: Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue

The “I Must Return to this Work with a Translation that is not Rife with Monotheism”: Iliad

Author of the Year: Paul Strathern for his many books on Italian history

Audiobook Narrator of the Year: T. Ryder Smith for Perhaps The Stars

---

I did not get close to 50 this year, partially out of getting into and becoming involved with the 2Rash2Unadvised podcast (a readthrough podcast of the Terra Ignota series, of which Perhaps The Stars is the final book), which I sometimes guest on, partially due to work things, partially due to bizarre weirdness in my life, partially due to a few long books (not all of which I finished). I’m optimistic about what I can read for much of next year. I did read a lot of history and a few books on the nature of war. Next year, I want to read more fiction and more contemporary works while keeping up the history, war, classics, and returning to foreign policy. I also hope to get more writing done.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because this existential competition is zero-sum it creates a situation where states push further and further for security without actually achieving any security gains, because every action they take to improve security is matched by their neighbors. Azar Gat calls this, somewhat colorfully, the ‘Red Queen effect’ (because everyone is running and running and going nowhere), but as a product of the security dilemma we can also understand this as ‘convergence’ – where any behavior that advantages a state’s power is swiftly adopted by all other states in the local system, so that over time states come to resemble each other in their militarism and ruthlessness. For students of history wondering why European militaries of 1400 were very regionalized and unique with lots of local patterns but by 1700, a standard form of linear infantry fighting by professional soldiers was practiced from Moscow to Lisbon, convergence is why.

I was thinking of this the other in the context of kungfu stories in which you meet colorful characters wielding a neverending variety of improbable and highly specific personal weapons, which in reality would most likely be quickly whittled down to a few that actually worked.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

BALIOC’S READING LIST, 2019 EDITION

This list counts only published books, consumed in published-book format, that I read for the first time and finished. No rereads, nothing abandoned halfway through, no Internet detritus of any kind, etc. Also no children’s picture books.

1. In a Time of Treason, David Keck

2. A King In Cobwebs, David Keck

3. War In Human Civilization, Azar Gat

4. The Kingdom of Copper, S. A. Chakraborty

5. The Impossibility of Religious Freedom, Winifred Fallers Sullivan

6. The Winter of the Witch, Katherine Arden

7. Out of the Silent Planet, C. S. Lewis

8. Perelandra, C. S. Lewis

9. The Great Divorce, C. S. Lewis

10. Underlord, Will Wight

11. The Devil-Wives of Li Fong, E. Hoffman Price

12. How to Hide an Empire: The History of the Greater United States, Daniel Immerwahr

13. The Raven Tower, Ann Leckie

14. The Rage of Dragons, Evan Winter

15. The Bird King, G. Willow Wilson

16. A Betrayal In Winter, Daniel Abraham

17. An Autumn War, Daniel Abraham

18. The Price of Spring, Daniel Abraham

19. Chartism, Thomas Carlyle

20. Impro: Improvisation and the Theater, Keith Johnstone

21. A Memory Called Empire, Arkady Martine

22. Foundryside, Robert Jackson Bennett

23. Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest Stats, James C. Scott

24. The Ruin of Kings, Jenn Lyons

25. Ship of Smoke and Steel, Django Wexler

26. Pan, Knut Hamsun

27. The Unbound Empire, Melissa Caruso

28. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation For Failure, Greg Lukianoff & Jonathan Haidt

29. Empire of Sand, Tasha Suri

30. Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson

31. A Brightness Long Ago, Guy Gavriel Kay

32. The Riddle-Master of Hed, Patricia McKillip

33. Heir of Sea and Fire, Patricia McKillip

34. Harpist In the Wind, Patricia McKillip

35. Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, Francis Fukuyama

36. Every Heart a Doorway, Seanan McGuire

37. The Witchwood Crown, Tad Williams

38. Empire of Grass, Tad Williams

39. Ten Restaurants That Changed America, Paul Freedman

40. The Priory of the Orange Tree, Samantha Shannon

41. The Dictator's Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics, Bruce Bueno de Mesquita & Alastair Smith

42. Wyrms, Orson Scott Card

43. Seedfolks, Paul Fleischman

44. The Axe and the Throne, M. D. Ireman

45. The Sun King, Nancy Mitford

46. The Demons of King Solomon, various (ed. Aaron J. French)

47. Towards a New Socialism, W. Paul Cockshott & Allin F. Cottrell

48. The Oracle Glass, Judith Merkle Riley

49. The Orphans of Raspay, Lois McMaster Bujold

50. Blood Meridian, or, the Evening Redness In the West, Cormac McCarthy

51. Lent, Jo Walton

52. Empress of Forever, Max Gladstone

53. Born a Crime: Stories From a South African Childhood, Trevor Noah

54. The Intuitionist, Colson Whitehead

55. The People's Republic of Walmart: How the World's Biggest Corporations are Laying the Foundation for Socialism, Leigh Phillips & Michal Rozworski

56. Turning Darkness Into Light, Marie Brennan

57. The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, David Mitchell

58. The Initiate Brother, Sean Russell

59. Gatherer of Clouds, Sean Russell

60. Primal Screams: How the Sexual Revolution Created Identity Politics, Mary Eberstadt

61. The New Achilles, Christian Cameron

62. World Without End, Sean Russell

63. Sea Without a Shore, Sean Russell

64. Uncrowned, Will Wight

65. A Brief History of Indonesia: Sultans, Spices, and Tsunamis: The Incredible Story of Southeast Asia's Largest Nation, Tim Hannigan

66. The Vagrant, Peter Newman

67. Jade War, Fonda Lee

68. The Affluent Society, John Kenneth Galbraith

69. The Hod King, Josiah Bancroft

70. The Name of All Things, Jenn Lyons

71. Cold Iron, Miles Cameron [Christian Cameron]

72. Dark Forge, Miles Cameron [Christian Cameron]

73. Emily of New Moon, Lucy Maude Montgomery

74. Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory, Ben Mcintyre

75. The Ten Thousand Doors of January, Alix E. Harrow

76. Feathered Serpent, Dark Heart of Sky: Myths of Mexico, David Bowles

77. Flowers In the Mirror, Li Ruzhen

78. Bright Steel, Miles Cameron [Christian Cameron]

79. On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, Dave Grossman

80. That Hideous Strength, C. S. Lewis

***********

Plausible works of improving nonfiction consumed in 2019: 19

Works consumed in 2019 by women: 24

Works consumed in 2019 by men: 55

Works consumed in 2018 by both men and women: 1

Balioc’s Choice Award, fiction division: Lent

>>>> Honorable mention: A Betrayal in Winter et al

Balioc’s Choice Award, nonfiction division: Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre

>>>> Honorable mention: War In Human Civilization

Cultural Heritage Award For “Holy Crap This Will Fuck You Up”: The Great Divorce

Cultural Heritage Award For “This Will Not Fuck You Up Nearly as Much as the Author Thinks It Will, or Maybe I Was Just In a Cranky Un-Receptive Frame of Mind”: That Hideous Strength

**********

A year of progress, I think. This is probably About Enough Reading. More nonfiction than before, although not enough (and too many things that I wanted to be Really Enlightening turned out to be duds). More literary classics too. A lot of modern genre fiction that was pretty-good-but-definitely-not-great.

15 notes

·

View notes