#bookforum

Text

There is nothing suspicious—or particularly gendered—about a desire to rest. But if we can sympathize in this respect with women who are drawn to the housewife fantasy, then we must also address the housewife’s immature side: her refusal of responsibility in the public sphere. The housewife lifestyle abandons the struggles of feminist advancement, community building, justice, and political engagement. It trades them for insularity, callowness, and superficial self-regard.

And here we return to Davis’s initial characterization of housewifery’s appeal: “I might have liked to hitch my wagon to someone, confident that he loved me enough that I could be comfortable in a state of financial dependency,” she writes. This desire to be taken care of, to be loved in a way that obviates responsibility, is not a fantasy of a marriage. It is a fantasy of a return to childhood. She’s not looking for a husband; she’s looking for a parent.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

lauren oyler takedown that is all the talk of literary twitter

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our tanned balls, our white selves

"...given the general state of culture these days, the mere act of writing a novel—whatever its politics or lack thereof—should be understood as a de facto leftist gesture because the contemporary right are illiterate, hateful ghouls. They don’t read books or book reviews or anything else. They binge Twitch streams, tan their balls, try to get librarians fired, and hang out in the smoldering ruins of Twitter sharing anti-Semitic memes and security-camera footage of people being murdered in the street. If you are reading this, they hate you. If you walk out of your house today and are stabbed to death with this issue of Bookforum tucked under your arm, these people will spend a week retweeting images of your dead body and joking about how that’s one weird trick for canceling student debt. While it is emphatically true that there are complicated, worthwhile intra-leftist fights to be had about what constitutes equitable discourse in our communities and our art—and specifically about how to balance an unwavering conviction in freedom of speech with the recognition that certain speech-acts have the potential to do real harm—it is also emphatically true that none of us should be censoring ourselves or each other on account of the hypothetical risk of some gooning jackboot with a Sailor Moon avatar and a sonnenrad tattoo laughing at our best jokes for the wrong reasons."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanks to his hard-won lack of self-awareness, Mishima is oblivious to the conceptual fissures within Sun and Steel, such as the unresolved tension, if not hopeless contradiction, between “seeing without words,” on the one hand, and fetishizing the ultra-erotic beauty of the doomed hero, on the other. The gaze is not a vector of pure libido; it cannot select its targets without language, culture, ideas about what makes something fuckable. You cannot immortalize a hero without representing him, whether in Homeric epic or in a maladroitly Photoshopped poster. Your body cannot disappear into the black hole of ecstatic annihilation and crystallize into an eternal monument at the same time. But Mishima’s peerless power is so totalizing that it apparently neutralizes contradictions by fiat, so that, for example, the most decadent vice of all—the aestheticization and eroticization of deadly violence—can be proposed as a manly virtue, and a philosophy that prizes experience above all else can enfold a vision of sex as the static communion of a calcified body and a desiring gaze. Who wouldn’t be tempted by the promise of a power that simply cuts through the Gordian knots of confusion, ambivalence, cognitive dissonance, all the things that might impel us to consult our self-critical consciences?

If nobody has enough to lose from a revolution to bother plotting its reversal, then it’s not a revolution at all—which means that any year of revolution is necessarily a year of counterrevolution, too. Sun and Steel is a transmission from the dark side of the moon, an artifact of that other 1968, the one Apple never tried to co-opt. That’s what everyone was worried about on the fortieth anniversary of ’68—co-optation, the neoliberal appropriation of the counterculture ethos, the commodification of dissent, the new spirit of capitalism. But all the while, this other beast was slouching along, knowing its time was not yet at hand but would be, in due course, and that a few more years of trickle-up economics would help pave the way. As the historian Timothy Snyder recently observed, with respect to the contemporary recycling of political ideas from the ’20s and ’30s: “Fascism is becoming a story oligarchy tells about itself.” Mishima, like the Italian Futurists before him, reminds us that sometimes, fascism is also a story that the avant-garde tells about itself.

- Elizabeth Schambelan, "In the Fascist Weight Room"

RIP Bookforum, have one of my fav pieces of literary criticism from the past few years in remembrance

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

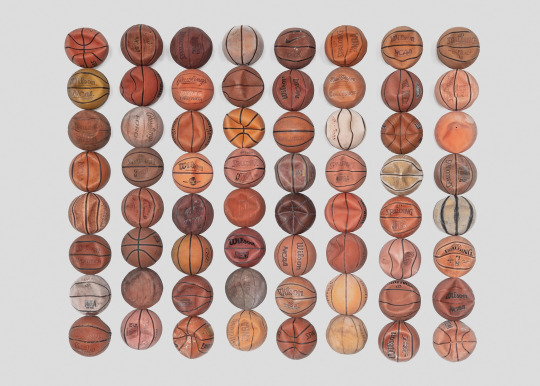

Hail Mary, Tyrrell Winston @ Library Street Collective, January 15, 2022 — March 3, 2022

#2 Tyrrell Winston, Apollo, 2022, Used basketballs, liquid plastic, steel, epoxy, 72h x 92w in

#3 Tyrrell Winston, Never Out (Muhammad Ali), 2021, House paint and charcoal on canvas in artist frame / 96h x 72w in

#2022#tyrrell winston#art#contemporary art#exhibition#library street collective#gallery#basketball#paint#oil#charcoal#canvas#bookforum#movesmood#dannyfariiia#danny faria

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have complicated feelings about wanting to disappear, because I already struggle with feeling invisible, and I know that visibility can be construed as a privilege, but I also never want to be fully seen. I even like, on occasion, to be misheard. What I struggle with more is being misunderstood.

Durga Chew-Bose (x)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since Montaigne, the best essays have been, as the French word suggests, trials, attempts. They entail the writer struggling toward greater knowledge through sustained research, painful introspection, and provocative inquiry. And they allow the reader to walk away with a freeing sense of the possibilities of life, the sensation that one can think more deeply and more bravely—that there is more outside one’s experience than one has thought, and perhaps more within it, too. These essays, by contrast, are incapable of—indeed, hostile to the notion of—ushering readers, or Oyler herself, into new territory, or new thought. The pieces in No Judgment are airless, involuted exercises in typing by a person who’s spent too much time thinking about petty infighting and too little time thinking about anything else.

Ann Manov, Star Struck

0 notes

Text

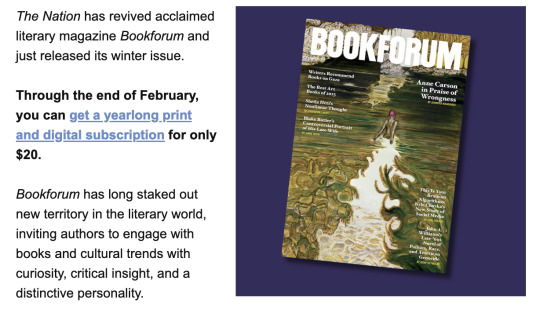

I'd only read one physical copy of the magazine and visited the website from time to time, but it was still disappointing to hear that Bookforum was folding.

I immediately wondered if this was another sign of decreasing literacy and interest in books, which in turn means that there's likely a decline in higher order thinking skills. (As always, I'm puzzled at the lack of a sense of urgency about this problem.)

I know I'm a little late to the party, but it's good news that The Nation caught Bookforum's fall.

0 notes

Text

Bye Bookforum, see 'ya, wouldn't want to be'ya.

(Actually I would, desperately...)

1 note

·

View note

Link

By David L. Ulin

Dec. 13, 2022 9:11 AM PT

What was it about Bookforum? The announcement on Monday morning that the current issue of the publication, founded in 1994, would be the last, has provoked an outpouring … not of protest (although that too) so much as of grieving. I feel it, too, this sense of loss and anger, this feeling that something essential is being needlessly destroyed.

That’s because for so many of us in the book world, this quarterly review journal represented a kind of critical apotheosis, positioned in the middle territory between service journalism and the academy. As both reader and writer (I published several reviews and essays there between 1998 and 2008), there was something special in the way Bookforum privileged voices — those of the critics as well as of the writers under review. To engage with an issue has long felt to me like going to a fabulous party where the guests are not just brilliant but also personable. This is how criticism is supposed to operate, to get your blood up. It reminds you of how much all this matters. It reminds you that literature is a collective soul.

Collective soul is how I might describe Bookforum also. It was edgy, opinionated, willing to be provocative, and it encouraged the same of its contributors. The first piece I wrote for the magazine was a takedown of William Gass’ collection of novellas “Cartesian Sonata” — bloodless, as Gass’ fiction often was. Rather than leave it at that, however, I was encouraged to go further, to frame the collection not only on its own terms but also in relation to Gass’ monumental achievement as an essayist. To consider his writing more broadly, in other words.

This was a hallmark of the journal, which pushed me to think about both my own work and that of others. It encouraged me to read ambitiously. Moira Donegan on Sarah Schulman, Meghan O’Rourke on Lynne Tillman, Tillman on Don DeLillo’s “Underworld.” Such pieces remain models as much as they are reviews or essays. They rewire our understanding of what criticism is, and what it can do.

This is not to say Bookforum was without antecedent; it’s impossible to imagine it existing, for instance, without the example of publications such as the New York Review of Books, the Village Voice Literary Supplement and the London Review of Books. All of them also published extended review essays and urged contributors to push the boundaries of their work. At the same time, the magazine felt to me a bit more open, or perhaps it’s more accurate to say: less doctrinaire. The work that resonates (Ismail Muhammad on Charlottesville, Heather Havrilesky on “Wonder Woman”) framed books through the lens of a wider cultural engagement; they sought to make connections beyond the page.

Perhaps the finest example of this — and among my favorite critical essays — is Lucy Sante’s 2007 exegesis on Georges Simenon. Here’s how Sante ends that piece: “You the reader are pulled into the situation, maybe against your better judgment, by an irresistible wish to figure out what exactly is wrong with the picture. And then, helplessly, you witness spiraling chaos …. Simenon’s genius — his native inheritance, refined into art — was for locating the criminal within every human being. At the very least, it is impossible to read him and remain convinced that you are incapable of violence. Every one of his books is a dark mirror.” Complicity, chaos, a sense of context: This is what, at its sharpest, criticism means to evoke.

Earlier this month, Penske Media Corp., which owns Rolling Stone and Variety, among other publications, purchased Bookforum’s parent company, Artforum International Magazine; although no reason has been given for the shutdown, it’s not hard to imagine this takeover as the cause. Either way, here’s what I know: I’m tired of losing outlets to conglomeration. I’m tired of culture being under siege because of money, of corporations and the wealthy buying platforms and destroying them just because they can.

I keep thinking about the Believer — sold out from under its editors by the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, only to be rescued after a public uproar. Something similar could also happen here. But if this really is the last issue of Bookforum, I want to remember its vitality. I want to remember the feeling of seeing each issue in my mailbox, checking the table of contents, bookmarking the work I wished to read. The current issue is no exception, which only makes the situation that much more fraught. This is not a dying journal, in other words, but a thriving one: Sasha-Frere Jones on Gordon Matta-Clark, Harmony Holiday on Hilton Als, Stephanie Burt on N.K. Jemisin. Here, we see the conversation that is being taken from us. There is no more elemental dialogue.

0 notes

Link

By David L. Ulin

Dec. 13, 2022 9:11 AM PT

What was it about Bookforum? The announcement on Monday morning that the current issue of the publication, founded in 1994, would be the last, has provoked an outpouring … not of protest (although that too) so much as of grieving. I feel it, too, this sense of loss and anger, this feeling that something essential is being needlessly destroyed.

That’s because for so many of us in the book world, this quarterly review journal represented a kind of critical apotheosis, positioned in the middle territory between service journalism and the academy. As both reader and writer (I published several reviews and essays there between 1998 and 2008), there was something special in the way Bookforum privileged voices — those of the critics as well as of the writers under review. To engage with an issue has long felt to me like going to a fabulous party where the guests are not just brilliant but also personable. This is how criticism is supposed to operate, to get your blood up. It reminds you of how much all this matters. It reminds you that literature is a collective soul.

Collective soul is how I might describe Bookforum also. It was edgy, opinionated, willing to be provocative, and it encouraged the same of its contributors. The first piece I wrote for the magazine was a takedown of William Gass’ collection of novellas “Cartesian Sonata” — bloodless, as Gass’ fiction often was. Rather than leave it at that, however, I was encouraged to go further, to frame the collection not only on its own terms but also in relation to Gass’ monumental achievement as an essayist. To consider his writing more broadly, in other words.

This was a hallmark of the journal, which pushed me to think about both my own work and that of others. It encouraged me to read ambitiously. Moira Donegan on Sarah Schulman, Meghan O’Rourke on Lynne Tillman, Tillman on Don DeLillo’s “Underworld.” Such pieces remain models as much as they are reviews or essays. They rewire our understanding of what criticism is, and what it can do.

This is not to say Bookforum was without antecedent; it’s impossible to imagine it existing, for instance, without the example of publications such as the New York Review of Books, the Village Voice Literary Supplement and the London Review of Books. All of them also published extended review essays and urged contributors to push the boundaries of their work. At the same time, the magazine felt to me a bit more open, or perhaps it’s more accurate to say: less doctrinaire. The work that resonates (Ismail Muhammad on Charlottesville, Heather Havrilesky on “Wonder Woman”) framed books through the lens of a wider cultural engagement; they sought to make connections beyond the page.

Perhaps the finest example of this — and among my favorite critical essays — is Lucy Sante’s 2007 exegesis on Georges Simenon. Here’s how Sante ends that piece: “You the reader are pulled into the situation, maybe against your better judgment, by an irresistible wish to figure out what exactly is wrong with the picture. And then, helplessly, you witness spiraling chaos …. Simenon’s genius — his native inheritance, refined into art — was for locating the criminal within every human being. At the very least, it is impossible to read him and remain convinced that you are incapable of violence. Every one of his books is a dark mirror.” Complicity, chaos, a sense of context: This is what, at its sharpest, criticism means to evoke.

Earlier this month, Penske Media Corp., which owns Rolling Stone and Variety, among other publications, purchased Bookforum’s parent company, Artforum International Magazine; although no reason has been given for the shutdown, it’s not hard to imagine this takeover as the cause. Either way, here’s what I know: I’m tired of losing outlets to conglomeration. I’m tired of culture being under siege because of money, of corporations and the wealthy buying platforms and destroying them just because they can.

I keep thinking about the Believer — sold out from under its editors by the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, only to be rescued after a public uproar. Something similar could also happen here. But if this really is the last issue of Bookforum, I want to remember its vitality. I want to remember the feeling of seeing each issue in my mailbox, checking the table of contents, bookmarking the work I wished to read. The current issue is no exception, which only makes the situation that much more fraught. This is not a dying journal, in other words, but a thriving one: Sasha-Frere Jones on Gordon Matta-Clark, Harmony Holiday on Hilton Als, Stephanie Burt on N.K. Jemisin. Here, we see the conversation that is being taken from us. There is no more elemental dialogue.

0 notes

Photo

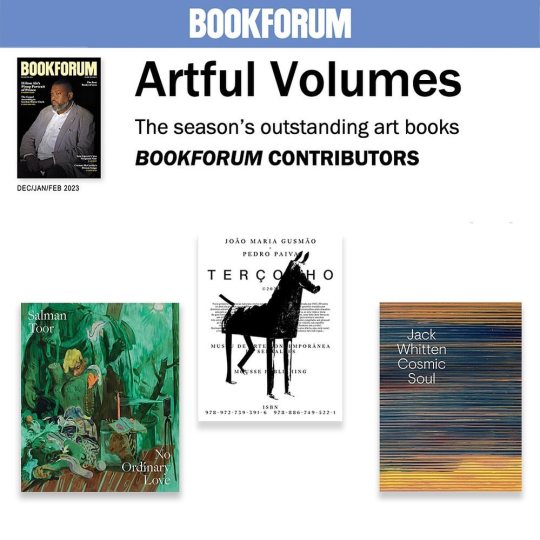

Good times at @bookforum this month. Can't do much better than this review of @salman.toor 'No Ordinary Love' from @gregoryrmiller & @baltimoremuseumofart "Echoing the murky sheen of sidewalk puddles, Salman Toor’s paintings revel in the absinthe-green palette of inebriation and hallucination. His compositions whisper of the dark delights of unlit alleyways, of clandestine trysts in the garden, or the unexpected thwack of a cricket bat against a stranger’s skull. Desire seeps through his canvases like spilled wine, but it’s the kind of longing laced through with recalcitrance, that sour taste in the mouth after a middling kiss." —Kate Sutton Then again: "Published on the occasion of the 2021 retrospective, 'João Maria Gusmão + @pedrocabritapaiva : Terçolho' from @moussemagazine lets readers into the pair’s proverbial kitchen, assembling the odds, ends, and images that have fueled their aesthetic flirtations with the psychological, the parascientific, the paranormal, and—to quote the artists—'abyssological.' Predating the visual hijinks of TikTok, Gusmão and Paiva’s films adhere to explicitly analog technologies, testing the limits of what can be recorded." —Kate Sutton And a personal favorite: "The late artist Jack Whitten told a studio visitor: 'The old symbols that we had from previous established religion, they’re not workable anymore for this society. We have to invent new symbols.' New symbols, new techniques, and new tools—what Whitten needed didn’t exist, so he had to devise it. He might slice tesserae out of thick paint and tile the squares like a mosaic or drag a self-fashioned twelve-foot rake through a wet painted surface. No standard monograph could quite hold Whitten’s artistic imagining, so 'Jack Whitten: Cosmic Soul' by Richard Shiff from @hauserwirth reimagines the art book as something that feels improvisatory and free, letting Whitten’s six decades of art roam aside commentary that keeps up rather than corrals." — @sonomar Read the full reviews via linkinbio. #bookforum #artfulvolumes #salmantoor #noordinarylove #joaomariagusmao #pedrocabritapaiva #jackwhitten #jackwhittencosmicsoul #cosmicsoul https://www.instagram.com/p/Cl6rcRcOY8K/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#bookforum#artfulvolumes#salmantoor#noordinarylove#joaomariagusmao#pedrocabritapaiva#jackwhitten#jackwhittencosmicsoul#cosmicsoul

0 notes

Photo

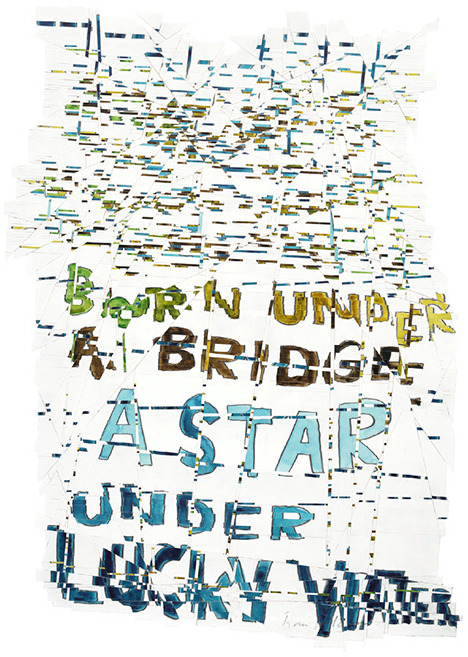

Roni Horn, Hack Wit – lucky water, (watercolor, graphite, and gum arabic on watercolor paper, cellophane tape), 2014 [«Bookforum» Magazine. Hauser & Wirth, Zürich. © Roni Horn]

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wishful thinking is very strong – you don't see it coming, because you don't want to see it coming.

— Margaret Atwood

#margaret atwood#hay festival#lviv bookforum#literary quotes#quote#quotes#book author#the handmaid's tale#hagseed

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bookforum: In The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, you write: "Just as all truly good writing is an assault on cliché, an individual truly to live, to be himself—to “selve,” in the words of Fr. Gerard Manley Hopkins—must avoid stereotype at all costs, to flee the predictable, the conventional, the habitual, and to seek and find one’s original self, to discover one’s original meaning.

So, why do you say that “all truly good writing is an assault on cliché”? And, how would you define one’s “original self” and one’s “original meaning”?

Theroux: There is an original self in everyone, often sadly lost as the years go by. How many unique people are there on any given bus-load of people? I would say many—potential inventors, painters, sculptors, farmers, writers, explorers—but time, habit, fears, diffidence, circumstances of all sorts, illness, lack of funds, indeed, even indifference, sloth, bad choices, have covered any potentialities like a fine dust, so that in the end they are lost. Gone is the “thisness” of that person, the unique and miraculous haeccitas: potency never become act. Just as a person who does not drink can ever know whether he or she is an alcoholic, the unplumbed self, if never examined, never sought, never tried out, will ever be known.

Bookforum: In Enemies of Promise, Cyril Connolly describes Ronald Firbank as hating “vulgarity and vulgarity of writing as much as vulgarity of the heart. Indeed, the writers with the most exquisite choice of words, those who take obvious pains to avoid the outworn and the obvious, to achieve distinction of phrasing, are equally susceptible to the fine points of the human heart.”

Can one definitively make a correlation between a writer’s language and their vulnerability “to the fine points of the human heart”?

Theroux: W. H. Auden said that the trouble one had with one’s vocabulary represents the trouble one has with one’s self, or words to that effect. I believe that false and vulgar artless language in books constitutes a real kind of a fraud. When Firbank has a character say, “I adore finials,” he is daring to be original as a writer. Hack writers always rely on the same dull, gray images—why bother to reach? Most of the novels on the Best-Seller List in Fiction are a waste of trees. I cannot fathom how any writer can write a novel and put away style. Isn’t the alternative a kind of verbal Muzak? Clichés are like coins too long in circulation, flattened to the touch. I recently reviewed a novel by a popular novelist that had not an original or memorable sentence in the entire book. No, a writer’s language has everything to do with the human heart. It may be a real beating heart or a dumb boulder. Does anyone care? America’s best-selling beer tastes like warm piss.

(x)

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

that bookforum review is exploding but as a sometimes-writer who tries really hard to write cultural criticism that is rigorous and well-researched and open to the thing i am considering on its own terms instead of some stupid terms that i or someone else invented and that are derived from and only apply to my own stupid life, it is soooo cathartic to have read three brutally negative reviews of l*uren *yler's book in a row, because she fundamentally sucks at doing the thing she is doing

14 notes

·

View notes