#kingdom of dalriada

Photo

Legendary kings of Scotland by James de Witt.

69: Kennethus II (Kenneth MacAlpin)

Kenneth MacAlpin (810-858) or Kenneth I was King of Dál Riada (841–850), King of the Picts (843–858), and the first King of Alba (843–858) of likely Gaelic origin. He inherited the throne of Dál Riada from his father Alpín mac Echdach, founder of the Alpínid dynasty. Kenneth I conquered the kingdom of the Picts in 843–850 and began a campaign to seize all of Scotland and assimilate the Picts, for which he was posthumously nicknamed An Ferbasach ("The Conqueror").

Kenneth I is traditionally considered the founder of Scotland, which was then known as Alba, although like his immediate successors, he bore the title of King of the Picts. One chronicle calls Kenneth the first Scottish lawgiver but there is no information about the laws he passed.

#kingdom of scotland#kenneth macAlpin#king of scotland#alpínid dynasty#house of alpin#george buchanan#list of scottish kings#legendary kings of scotland#rerum scoticarum historia#list of monarchs#scottish history#kings of dál riata#Chronicle of the Kings of Dál Riata#kingdom of dalriada#kings of the picts#full-length portrait#full length portrait#Coinneach mac Ailpein#Cináed mac Ailpin

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy St Andrews Day.

As part of our Patron Saint’s Feast Day the Scottish Saltire is proudly flown and many people add it to their posts on social media to celebrate the day, but how did Scotland adopt the saltire?

There is no actual date, or in fact nothing in our written history of the time, but legend has it that in AD 832 the king of the Picts, ‘Aengus MacFergus’, ( Anglified to Angus but some stories say Hungus) with the support of 'Scots’ from Dalriada, won a great battle against King Athelstane of the Northumbrians. The site of the legendary battle became known as Athelstaneford in present-day East Lothian.

St Andrew visited the Pictish leader in a dream before the battle and told him that victory would be won. When the battle itself was raging, a miraculous vision of the St Andrew’s Cross was seen shining in the sky, giving a boost to the morale and fighting spirit of his warriors. The result was a victory over the Saxons, and the death of Athelstan. Thus, after this victory, according to the tradition, the Saltire or St Andrew’s Cross became the flag of Scotland, and St Andrew the national patron saint.

While there is no written reference to the battle in Scotland from the period it was said to have taken place, this is not surprising, as it was a time for which we have little or no documentation for anything. The earliest written mention of the Battle of Athelstaneford in Scottish history comes from years later in the newspapers of the day, if you follow my posts then you know I dip into these “Chronicles from time to time, the first one to mention Athelstaneford is the Scotichronicon, written by the Scottish historian Walter Bower.

The Scotichronicon has been described by some Scottish historians as a valuable source of historical information, especially for the times that were recent to him or within his own memory. But he also wrote about earlier times, and this included the battle at Athelstaneford.

Bower’s account includes the scene where Aengus MacFergus is visited by St Andrew in a dream before the battle. He was told that the cross of Christ would be carried before him by an angel, there was no mention of a St Andrew’s Cross in the sky in this version. It was in later accounts, from the 16th centuries onwards, that we have the description of an image of St Andrew’s Cross shining in the sky

Bower was writing in the early 1400s. The bitter and bloody struggle to retain Scotland’s independence was not just a recent memory but also a current reality for him. Parts of Scotland were still occupied by England, and Bower had been involved in raising the money to release Scotland’s king, James I, from English captivity.

Also, Scotland’s early historical records and documents had been deliberately destroyed during the invasion by the English king Edward I. This was done in part as an attempt to remove historical evidence that Scotland had been an independent kingdom. The idea was simple: take away a nation’s history and you strip it of its identity and justification for its independent existence. The theft of the Stone of Destiny was part of this process, the Black Rood which was believed to contain a piece of the Cross Jesus was crucified on was also removed, I have covered both these in previous posts.

Part of Bower’s motivation in writing his Scotichronicon was to help restore this stolen history. He was a scholar and a man of the church. In his time, the figure of St Andrew had become a prominent presence in Scottish society.

The greatest church building in the land during his time was the Cathedral of St Andrew, which housed relics of St Andrew himself. It had taken over a hundred years to build and wasn’t formally consecrated until 1318, just four years after Bannockburn. The ceremony of course included Robert the Bruce and at it thanks was given to St Andrew for Scotland’s victory.

Less than 100 years after this, in 1413, the University of St Andrews was established and Walter Bower was one of its first students. By this time, the Cathedral of St Andrew was a place of pilgrimage, with thousands travelling there to venerate the saint’s relics. A pilgrimage route from the south took in the shrine of Our Lady at Whitekirk, not far from the site of the battle, and many pilgrims took a ferry across the Firth from North Berwick, where the ruins and remains of the old St Andrew’s Kirk can still be seen close to the Scottish Seabird Centre.

So as he sat down to write his history of earlier times, he was able to trace this connection to St Andrew, using the limited earlier written accounts, such as those of earlier Chronicler I’ve mentioned before, John Fordun, who lived in the 1300s. While Fordun doesn’t specifically mention the location of Athelstaneford, he records a battle which took place between the Picts led by Aengus and a force from the south led by Athelstan, and said the location of the battle was about two miles from Haddington. The account of St Andrew appearing in a dream to Aengus is also described by Fordun.

This creates a powerful link to the development of the written version of the story. Let’s remember Bower came from what is now East Lothian. Let us also remember that people in the early centuries stored and passed on much of their historical knowledge not in the written word but in memory and handed down oral traditions. People told stories, remembered them and told them to the next generation. Undeniably, some details would be forgotten or changed over time, but the bones of the story would be handed down. And that would include reference to locations of significant events in the local landscape.

Bower will have had access to this rich oral tradition of local stories based on handed-down collective memories of past events, which is perhaps why he was able to name the location. The later writers who added to the story of the battle will likewise have found new sources in the oral tradition to add to the narrative. Even in the 19th century, cartographers mapping the area were able to identify locations traditionally associated with the battle from local people who were custodians of ancestral memory.

This is how the story of the Battle of Athelstaneford and its connection with St Andrew and the Saltire has evolved.

The village is home to the National Flag Heritage Centre which occupies a lectern doocot built in 1583 and rebuilt in 1996. It is at the back of the village church. Today the village is surrounded by farmland and has little in the way of amenities. Tourists can follow the "Saltire Trail", a road route which passes by various local landmarks and places of historical interest.

Athelstaneford Parish Kirk has a connection with the subject of my post last week, author Nigel Tranter, who was a prominent supporter of the Scottish Flag Trust. He married in the church, and in April 2008 a permanent exhibition of his memorabilia was mounted in the north transept of the church. Items include a copy of Nigel Tranter's old typewriter, a collection of manuscripts and books, and other personal items. The display was previously at Lennoxlove House, and prior to that at Abbotsford House, the home of Sir Walter Scott.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Should I Write Next?

Thank you to everyone for your very kind words on the conclusion of Don’t Let Me Fall. Since I managed to wrap that story up before the holidays, and since we’re due for the first big snowstorm of the season that will keep me indoors all weekend, I’m trying to decide what to write next.

I am not promising to write the most popular choice, but I am interested to know how readers feel about the following contenders:

Dal Riada (working title) - a WIP that is a retelling of Outlander with Claire falling from the 1860s back to the proto-Gaelic kingdom of Dalriada in 806, where Seumas (Jamie) is the nephew of the king. It also tells the story behind the Woman of Balnain folktale that Claire hears sung in Outlander. Omniscient POV. I’ve written 6 chapters (about 19,000 words) and done a ton of historical research, but I need to revisit the plot and do a significant re-write of what’s there. This is the story I most want to write, but it will take a looong time to do it justice. Likely completion: Summer 2023.

Laredo (working title) - a WIP set in the American southwest in the 1980s. Jamie is a vaquero (Spanish-American cowboy) on his family’s ranch in southern Texas when Dr. Claire Beauchamp’s car breaks down in his one-saloon town. He’s a fugitive from the law, she’s running away from financial and personal ruin, and they come to each other’s aid. Claire POV. This is the story closest to completion. I’ve got 13 chapters (about 37,000 words) written, and there’s just one major plot hole to fill and a lot of polishing before it’s done. Likely completion: January/February 2023.

West End Girl - a WIP set in mid-1980s London during the height of the cocaine/heroin epidemic. Claire is a wealthy Mayfair society girl who witnesses something she shouldn’t. Jamie is the leader of a Docklands street gang called the Clan who protects Claire from Black Jack Randall, her boyfriend’s cousin. It’s a lot darker than my usual stuff. Omniscient POV. This one is about half-written (12,000 words) but still needs some plotting and some rework as well. Likely completion: March 2023.

The Man from Black Water - another wacky fic idea that came to me not long ago. A cross-over between Outlander and the 1980s movie The Man from Snowy River, retold in 1880s Scotland rather than 1880s Australia. The plot would be almost identical to the movie (for those that have seen it) and I can practically recite that movie from memory, so this is a quick hit of feel-good fic. Likely completion: January/February 2023.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghosts Stars Names

Clarence - Clear/ One who lives near the River Clare

Clarence had both Scottish roots in the ancient kingdom of Dalriada and Irish heritage as it may be in relation to the Clare River in the West of Ireland. It could also be in relation to the title Duke of Clarence from the 14th century, implying royal heritage. It is a name that was very popular during the late 19th century and early 20th century, so he may have been born around the time Fanny was living on Button House. He also may have died before Captain was stationed at Button House and thus would’ve been around during the 1920s-1938. It’s also possible he’s from the late 14th century around the time of Edward IV and Richard III’s reigns.

Since all the names at least briefly allude to the character’s personality or status within their lives, Clarence may have been some kind of moral guidance or advisor, due to his name being associated with clear and water. He could’ve been a calm person who went with the flow and thus would’ve been a compatible friend for Robin. His name also being a title given to a 14th century royal prince who married someone of the Claire family may also imply royal heritage.

Godric - God ruler

Godric originated in Anglo-Saxon England, with many saints and sheriffs of the 11th century having that name. The name could form from anywhere between the 5th and 11th centuries. Like most names during that time, it holds religious significance. The name died out after the Norman conquest, so it is likely Godric was from before William the Conqueror, so at least before 1066. He would have come from Early Medieval Europe.

Since his name is in relation to God, there isn’t much we can gain from its meaning. Similar to the plague ghosts his name is a product of his time and would mostly be religious in some way. However, he may have been around during the time of the Romans invading, or a bit later when the seven kingdoms were established. We’ll never really know until we’re shown him. He could be of German descent.

Elizabeth - God is my oath

Elizabeth has roots in both Hebrew and Greek, coming from the Hebrew words shava meaning oath and el meaning god. It was a name more common in Eastern Europe from the 12th century. In Medieval England it was sometimes used to honour a saint. Due to Elizabeth I’s reign it became very popular during the 16th century, though it stayed a top ten name until 1945.

The name Elizabeth is was also a Dutch family name Elisabeth, which may imply Dutch heritage. She could have either been from around the Middle Ages, during Elizabeth I’s reign, or just after death. The name implies importance and someone who is very regal, so she may have been part of the aristocracy during James I/VI’s reign. She may have been around a similar time to Humphrey, or may have been born in the second half of Elizabeth’s reign.

William - Resolute protector/strong-willed warrior

The name is of Germanic origin but was also popularised in England by the reign of William the Conqueror, it is also derived from the name Wilhelm. It is comprised of the elements Wil, meaning will of desire, and helm, helmet or protection. Similar to Elizabeth, William is a name that has been popular for centuries and has stayed in the top ten most common. It is typically knows as of old Norman origin.

His name implies he may have been a soldier or warrior of some sort, perhaps having fought in a war. It may also imply the polar opposite, that he was supposed to be a soldier but deserted the army he was a part of. Either way, he may have been named after the arrival of William the Conqueror or departure as a tribute when the king died. The ghost could also possibly be from that time but be compartment unrelated to conflict, being named later on during the reign of William and Mary or William IV.

#bbc ghosts#we know nothing about them so speculators of course#fanny button#the captain#thomas thorne#julian fawcett#pat butcher#humphrey bone#robin bbc ghosts#kitty bbc ghosts

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

I wanna expand my musical horizons, gimme some recs of your favorite songs?

Alright, sorry I'm getting to this so late! Because I'm a nerd (and because my favourite by them isn't one I suggest to new listeners), I'll recommend a Rush song from each album:

Here Again

Beneath, Between, and Behind

Bastille Day

2112

A Farewell to Kings

La Villa Strangiato

Natural Science

YYZ

The Weapon

The Enemy Within

Mystic Rhythms

Force Ten

Presto

Leave That Thing Alone

Bravado

Time and Motion

Peaceable Kingdom

Far Cry

BU2B

Now, for just my favourite tunes from other bands (granted, some bands I can't pick a favourite, so I'm just going with what pops up first in my mind):

Yes - The Gates of Delirium

Genesis - Supper's Ready

Emerson, Lake, & Palmer - Karn Evil 9

King Crimson - Starless

Ghost - Deus in Absentia

Powerwolf - Dancing with the Dead

Gojira - Global Warming

Korpiklaani - Juodaan Viinna

Elvenking - Moonbeam Stone Circle

Týr - Ride

U2 - Zooropa

Mastodon - Sickle and Peace

Amon Amarth - Cry of the Black Birds

Billy Talent - Horses and Chariots

Klaatu - Little Neutrino

Pink Floyd - Welcome to the Machine

Rammstein - Weit weg

Dalriada - Áldás

Dark Tranquillity - Empires Lost to Time

Finntroll - Mask

Gloryhammer - Rise of the Chaos Wizards

Haken - The Cockroach King

Huntress - Zenith

Igorrr - Unpleasant Sonata

Iron Maiden - Satellite 15

Jack Stauber - Two Time

Ministry - Jesus Built My Hotrod

Porcupine Tree - Collapse the Light into Earth

Radiohead - Give up the Ghost

Stratovarius - Elysium

Soen - Jinn

Swans - Blood Promise

Skeletonwitch - Fen of Shadows

System of a Down - Holy Mountains

Tool - Culling Voices

And there we go! Hope that isn't too much, haha

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE DESCRIPTION OF SAINT PATRICK

The Apostle of All Ireland

Feast Day: March 17

"Hear me, people of Ireland. For God has sent me back to you to show you His way. He is not a God who asks for these sacrifices. For He took our sins and sacrificed Himself for our salvation. He does not ask for your body to be burned, but for your heart, that He might fill it with His love, His abundance, and His light!"

Patrick was born in 385 in Roman Britain (now modern-day United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland).

At the age of 16, he was sold as a slave in Ireland, where he tended sheep in Dalriada. He lived for six years among mountains and forests, growing in faith and holiness, and during his time in captivity Patrick became fluent in the Irish language and culture.

After a miraculous escape, Patrick, after hearing a voice urging him, to travel to a distant port where a ship would be waiting to take him back to Britain. On his way back to Britain, Patrick was captured again and spent 60 days in captivity in Tours, France. During his short captivity within France, Patrick learned about French monasticism.

Shortly afterward, he was told in a dream by some Irish people (notably Victoricus) to go back and evangelize them.

In 431, having completed his theological studies in Lerins Abbey, he was sent as a missionary to Ireland. The following year, Pope Celestine I had him consecrated as bishop. His first mission was in the north of the island, where he had formerly pastured cattle as a slave. Then, he traveled the whole country, converting many pagans by the force of his faith and the many miracles granted by God.

Patrick's success aroused the envy of the pagan priests and the druids, who plotted to kill him. One day, he exchanged his seat with the one of the charioteer, who was killed in the journey by a spear intended for himself. After three decades (30 years) of labor and prayer, the Catholic church was successfully established through Ireland.

Patrick gave his last blessing from the summit of Cruachan Aigli (now Croagh Patrick), the 2,510-foot 'mount of the eagle' in County Mayo on Ireland's west coast.

There, after a fast of 40 days, he had a vision of thousands of future Irish saints, who were singing out: 'You are the father of us all!'

He died soon afterwards in 461 in Saul, Dal Fiatach, Ulaid, Gaelic Ireland (present-day Northern Ireland) and was buried at Saul, where he had built his first church (St Patrick's Cathedral, Armagh).

#random stuff#catholic#catholic saints#saint patrick#patrick of ireland#san patricio#pádraig#padrig#ireland#archdiocese of new york#archdiocese of newark#roman catholic archdiocese of los angeles#st. patricks day

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lia Fáil

Also known as the Stone of Destiny or Speaking Stone

Some Scottish chroniclers, such as John of Fordun and Hector Boece from the thirteenth century, treat the Lia Fáil the same as the Stone of Scone in Scotland.

According to this account, the Lia Fáil left Tara in AD 500 when the High King of Ireland Murtagh MacEirc loaned it to his great-uncle, Fergus (later known as Fergus the Great) for the latter's coronation in Scotland. Fergus's sub-kingdom, Dalriada, had by this time expanded to include the north-east part of Ulster and parts of western Scotland. Not long after Fergus's coronation in Scotland, he and his inner circle were caught in a freak storm off the County Antrim coast in which all perished.

The stone remained in Scotland, which is why Murtagh MacEirc is recorded in history as the last Irish King to be crowned on it.

However, historian William Forbes Skene commented: "It is somewhat remarkable that while the Scottish legend brings the stone at Scone from Ireland, the Irish legend brings the stone at Tara from Scotland

0 notes

Text

"The Spread of Christianity in the British Isles: Monastic Missions and Roman Authority Triumphs"

The spread of Arianism among Germanic tribes and the conversion of the Franks to Roman faith were noted. Catholic orthodoxy was gradually accepted by Germanic invaders. However, there was still much to do. The church's vitality during the collapsing empire and opening Middle Ages was shown through its successful extension of Christianity.

Ireland and Scotland

Christianity was present in British Isles before Constantine's conversion. The Roman Empire's downfall weakened it among the Celtic population, while the Anglo-Saxon invaders won much of southern and eastern England for heathenism. Christian beginnings were found mainly in southern Ireland before Patrick. However, he greatly advanced the cause of the Gospel in Ireland and organized its Christian institutions, earning the title of Apostle of Ireland.

Patrick was born in 389 and was the son of a deacon and grandson of a priest. He was trained in Christianity. In 405, he was taken as a slave in Ireland for six years. He was able to escape to the Continent and lived in the monastery of Lérins for some time. In 432, he was ordained a missionary bishop by Bishop Germanus of Auxerre. Patrick then began his work in Ireland, where he spent most of his time in the northeast, with some efforts in the south and west. Despite few facts surviving, there is no doubt about his zeal and his abilities as an organizer. He systematized and advanced Christianity in Ireland. Patrick brought the island into association with the Continent and with Rome.

Patrick introduced the diocesan episcopate into Ireland, but it was soon modified by the island's clan system, resulting in many monastic and tribal bishops. Finian of Clonard (470?-548) developed the unique Irish monasticism, which included strong missionary efforts and notably learned monasteries. The Irish monastic schools were famous in the sixth and seventh centuries, and the monasticism's greatest achievement was its missionary work.

The origins of Christianity in Scotland are unclear. Ninian and Kentigern spread the religion in the 4th and 5th centuries respectively, but not much is known about their work. There is a possibility that the Irish settlers who founded the kingdom of Dalriada in 490 were Christians. However, the most influential missionary was Columba. He founded a successful monastery on the island of Iona and went on to spread the Gospel among the Picts in the northern regions of Scotland. Christianity in Scotland was mainly monastic, with bishops under the authority of Columba and his successors as abbots of Iona.

Missionaries on the Continent

Irish missionaries brought Christianity to northern England, Lindisfarne. Aidan, a monk from lona, established a new Iona on the island in 634. Christianity was then widely spread in the region by Aidan and his associates. These Celtic monks were also active outside of the British Islands. Columbanus, a monk from the Irish monastery of Bangor, founded the monastery of Luxeuil in Burgundy. He later established the monastery of Bobbio in northern Italy, where he died a year later.

Columbanus was one of many Irish monks who worked in central and southern Germany. They introduced private confession to the laity, which was widely supported by the Irish monks. The Irish also created the first penitential books with appropriate satisfactions for specific sins. These books were made familiar on the Continent by the Irish monks.

Roman Missionaries in England

Pope Gregory the Great sent Augustine, a Roman friend, and several monastic companions to convert the Anglo-Saxons. After much struggle, Æthelberht and many of his followers accepted Christianity. Augustine was then appointed as a metropolitan bishop and was authorized to establish twelve bishops under his jurisdiction. It took almost a century for Christianity to become dominant in England, but the movement strengthened the papacy and produced some of the most energetic missionaries on the Continent.

The acceptance of Christianity in England was not without difficulty. After the death of Ethelberht, the power of Kent declined, and with it the initial Christian successes. Northumbria gradually emerged as the leader. In 627, King Edwin of Northumbria was converted to Christianity through the efforts of Paulinus, who later became bishop of York. However, in 633, the heathen King Penda of Mercia defeated and killed Edwin, leading to a heathen backlash in Northumbria.

Under the Christian King Oswald, who had converted while in exile in Iona, Christianity was re-established in Northumbria with the help of Aidan, who represented the Irish or "Old British" tradition (see ante, p. 197). Penda attacked again, and in 642, Oswald was killed in battle. His brother, Oswy, like him a convert of Iona, struggled to secure all of Northumbria, finally succeeding by 651 and earning widespread recognition as an overlord. English Christianity was becoming firmly established.

Roman Authority Triumphs

Since the arrival of the Roman missionaries, there had been disputes between them and their Irish or Old British counterparts. The differences seemed minor, such as the older system of reckoning used by the Irish and Old British, which resulted in diversity regarding the date of Easter. Additionally, the forms of tonsure and the administration of baptism differed. The Old British Church was monastic and tribal while Roman Christianity was diocesan and organized. The Old British missionaries considered the Pope as the highest dignitary in Christendom, but the Roman representatives held him to have judicial authority which the Old British did not fully accept. Southern Ireland accepted the Roman authority around 630, while England made its decision at a synod in Whitby in 664 under King Oswy. Bishop Colman of Lindisfarne defended the Old British usages, while Wilfrid, previously of Lindisfarne but having won for Rome on a pilgrimage and soon to be bishop of York, opposed. The Roman custom regarding Easter was approved, securing the Roman cause in England. By 703, Northern Ireland had followed the same path, and by 718, Scotland. In Wales, the process of accommodation was much slower and only completed in the twelfth century. Pope Vitalian's appointment of a Roman monk, Theodore, as Archbishop of Canterbury in 668 further strengthened the Roman connection in England. Theodore, an organizer of ability, did much to make permanent the work begun by his predecessors.

The combination of the two streams of missionary effort proved advantageous for English Christianity. While Rome contributed order, the Old British added missionary zeal and a love of learning. The scholarship of Irish monasteries was transplanted to England and strengthened by frequent Anglo-Saxon pilgrimages to Rome. Bede, also known as the "Venerable" (672?-735), was a prominent figure in this intellectual movement. He spent most of his life as a member of the joint monastery of Wearmouth and Jarrow in Northumbria. Like Isidore of Seville a century earlier, Bede's learning encompassed the full range of knowledge of his time, making him a teacher for generations to come. He wrote on chronology, natural phenomena, the Scriptures, and theology. He is most famously known for his "Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation," a highly regarded work that is the principal source of information regarding the Christianization of the British Islands.

Annotated Bibliography

- *The Conversion of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms* by Richard Fletcher: This book provides a comprehensive overview of the spread of Christianity in England, including the role of Roman and Celtic missionaries and the conflicts that arose between them.

- *Celtic Christianity: Making Myths and Chasing Dreams* by Ian Bradley: This book explores the origins and development of Celtic Christianity, including its unique monastic traditions and how it influenced the spread of Christianity in the British Isles.

- *Saint Patrick's World: The Christian Culture of Ireland's Apostolic Age* by Liam de Paor: This book provides a detailed account of the life and work of Saint Patrick, including his mission to Ireland and his efforts to establish Christianity on the island.

- *Bede: The Ecclesiastical History of the English People* translated by Leo Sherley-Price: This classic work by the Venerable Bede is a primary source for the history of Christianity in England, providing valuable insight into the early church and its leaders.

- *The Life of Saint Columba* by Adomnan of Iona: This biography of Saint Columba, written by one of his contemporaries, provides a detailed account of his life and work as a missionary in Scotland and his establishment of the monastery at Iona.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ireland is full of very special and sacred places. Joan and her friends visited some of the best with wonderful local guides like Auriel in Sligo, Mark at the Dalriada Kingdom Tours and Hugh in the Sperrin Mountains. Here you’re in harmony with nature and all the beauty around you. #ireland #caragrouptravel #travel #explorepage #explore #sligo https://bit.ly/3bX6Nck

0 notes

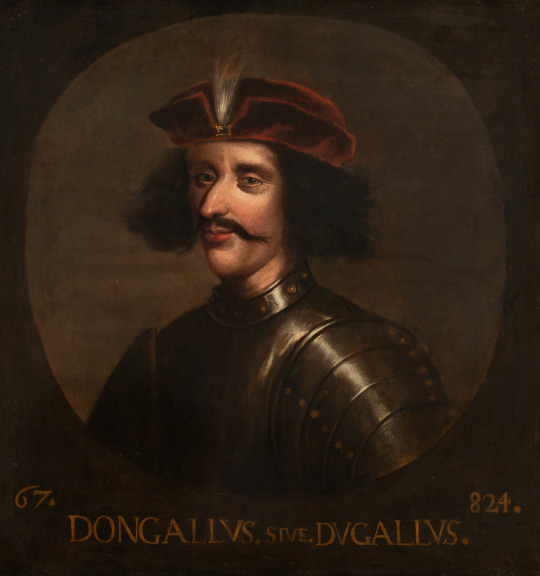

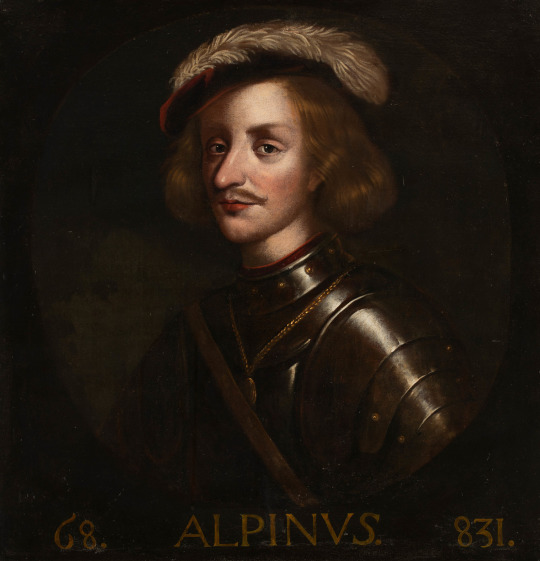

Photo

Legendary Kings of Scotland by James de Witt.

66: Congallus III or Convallus II (Conall Crandomna). He was king of Dál Riata (modern western Scotland) from about 650 until 660.

The Senchus fer n-Alban (an Old Irish medieval text) makes him a son of Eochaid Buide and thus a member of the Cenél nGabráin. He was co-ruler with Dúnchad mac Conaing until 654, after which he was apparently sole ruler.

His sons Máel Dúin mac Conaill and Domnall Donn may have been kings of Dál Riata.

His death in 659 or 660 is reported by the Annals of Ulster.

67: Dongallus (Domangart mac Domnaill). It is not clear whether he was king of Dál Riata or king of the Cenél nGabráin (the Cenél nGabráin was a kingroup, presumed to descend from Gabrán mac Domangairt, which dominated the kingship of Dál Riata until the late 7th century and continued to provide kings thereafter.)

68: Alpinus (Alpín mac Echdach). Cináed and Alpín are the names of Pictish kings in the 8th century: the brothers Ciniod and Elphin who ruled from 763 to 780.

Weir states that Alpín succeeded his father Eochaid IV as King 'of Scotland' (Dál Riata), and also became King of Kintyre in March/August 834, thus establishing his power over a wide area of Scotland.

Alpín died on 20 July or in August 834 when he was either killed whilst fighting the Picts in Galloway or beheaded after the battle. His place of burial is not recorded. He was succeeded by his son Kenneth MacAlpin.

#Conall Crandomna#dongallus#domangart mac domnaill#alpinus#alpin mac echdach#legendary kings of scotland#george buchanan#jacob jacobsz de wet ii#list of scottish kings#list of monarchs#rerum scoticarum historia#scottish history#de iure regni apus scotos#Chronicle of the Kings of Dál Riata#kings of dál riata#kingdom of dalriada#kings of the picts#scottish dna

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

13th February 862 Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed mac Ailpin); who united the Picts and Scots in one kingdom, died at Forteviot. His reign is given in the Pictish Chronicle as twenty eight years.

Kenneth, the son of Alpin went by a few names, Cináed mac Ailpín, Kenneth Mac Alpin, and Kenneth the Hardy, many regard him as the first King of Scotland.

Battling against Norse (Viking) raids, he brought some unification between the Gaels and the Picts to found a united kingdom of Alba or Scotia. The Picts had been weakened by incursions from the Vikings and Irish tribes who under Fergus Mor had settled in the area of Argyll. The term Scots came from the Latin Scotti which was Latin for Irish.

Kenneth was Dalriada son of King Alpin II of Dalriada and succeeded his father to the crown of Dalriada in 839 but he also had a claim to be King of the Picts through his mother, he was however not the only claimant to the Pictish throne.

The Picts agreed to a meeting with Mac Alpin at Scone, attended by all claimants to the Pictish Crown, Now this story is a bit far fetched but it is a story none the less of what is said to have happened at that meeting, it has since been referred to as Mac Alpin’s treason.

The leading Pict Claimant, Drust X and his nobles were all killed by the Scots: allegedly (and improbably) by having their booby-trapped benches collapsed so Kenneth’s rivals plunged into pits in the floor and impaled themselves on spikes set there for the purpose.

Suddenly there was only one claimant for the Pictish Crown, and Kenneth was crowned King of the Picts and the Scots in 843. He was the first King of the House of Alpin, the dynasty named after his father. Kenneth made his capital at Forteviot, a small village 5 miles south west of today’s Perth. He also moved the religious focus of his kingdom from Iona, where he was said to have been born, to Dunkeld, and had St Columba’s remains moved there in 849, perhaps for safe keeping from the continuing Vikings raids.

Kenneth MacAlpin was succeeded by Donald MacAlpin/ Domnall mac Ailpín his brother.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

ST PATRICK MISSIONARY TO THE IRISH c. 389 - 461

CENTURIES AGO A BUBBLING WELL IN THE HEART OF DUBLIN WAS THE SCENE OF COUNTLESS BAPTISMS AT THE HANDS OF THE CELEBRATED SAINT PATRICK.

Today, pilgrims stand and pray at the sacred site of the ancient well which lies outside the walls of St Patrick's Cathedral.

Devotees to the Saint still walk on pilgrimage to sites all over Dublin, following in the footsteps of the great Saint.

This devotion, many centuries after this man walked on Ireland's green hills, give rise to the question;

Who was Patrick?

Ancient Ireland

Ireland was the last piece of land on the journey west; it was known as 'the back of beyond'.

In Latin this translated as ultima Thule; the voyage's last stop.

Celtic culture held full sway over the island when the young Patricius arrived, having been captured as a slave.

In the fifth century AD, Ireland's population depended on mixed farming and the rearing of cattle and sheep.

There were no cities as we know them today. Instead, early Celtic settlements had ring-forts enclosing the dwellings.

Thick forests covered large areas of the land, and about one hundred chieftains ruled as clan kings.

Within one hundred years after the death of Patricius - eventually known as Patrick - the influence of this man of God had led to the warrior-kings converting to Christianity.

Patrick's early life

Patrick grew up in a place called Bannavem Taberniae - possibly in Britain.

His father, Calpurnius, was a local governing official who was also a deacon in the Church.

Potitus, Patrick's grandfather, was a priest - a presbyter.

The family lived in a villa on a farm, and owned slaves, to whom Patrick was very attached.

They were devout Christians, and Calpurnius' role in the Church included duties during worship and visiting Church members when they were sick or in need.

Around 400 AD, before his sixteenth birthday, Patrick was abducted from his home by slavers.

His enslavement abruptly interrupted his education, and in later years this sad fact deeply affected Patrick.

He felt that he had not been as well educated as many of his peers, and this had impact on his self image and mood.

However, this did not affect his ministry, which flourished under his God-given vocation to preach, teach, and covert to Christ.

Slavery in Ireland

Many thousands were enslaved alongside Patrick that fateful day.

A ship had come in from Ireland in search of plunder and valuable slave labour.

At that time, large slave markets flourished in early Dublin, with buyers coming in from all over the known world.

In the Iron Age, Roman power was gradually declining towards the end of the 3rd century.

Britain fell prey to attacks from those closest to her borders.

Irish chieftains raided across the water and expanded their territories eastward.

The kingdom of Dalriada in the north-east extended into northern Britain and Scotland.

This created a route for some of the first Irish missionaries.

Most famous of raiders and slavers was Niall of the Nine Hostages.

It is said he controlled land through hostages taken from the Scots, Saxons, Britons and Fench, as well as Irish. [1]

He is reportedly credited with capturing the young Patrick and bringing him back to Ireland as a slave in the middle of the 5th century.

Mound of the Hostages

It is believed, prior to being sold, Patrick was held at the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara.

Patrick became the slave of a master on a farm near the woods of Foclut, by the western sea in County Mayo.

It is believed that the master was a warrior chief, whose opponents' heads sat atop sharp poles around his palisade in Northern Ireland.

Patrick became a herder, protecting the animals from attack by wild animals.

He toiled in his duties, battered by wind and rain, on the side of Slemish Mountain. [2]

His life as slave in Ireland was a harsh one, and he endured long bouts of hunger and thirst. [3]

He also lived in complete isolation from other human beings for months at a time - a psychologically searing experience indeed.

Patrick worked as a slave from age 16 until he was 22 on this mountain.

The mountain - which rises to 1,500 feet - lies in County Antrim.

During this time of trial, Patrick's relationship to God - not very deep initially despite his Christian upbringing - strengthened and deepened.

One of his continually used prayers was eventually woven into a song called 'St Patrick's Breastplate' [the [Lorica]].

One verse reads;

'Christ be with me, Christ within me,

Christ behind me, Christ before me.

Christ beside me, Christ to win me,

Christ to comfort and restore me;

Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

Christ in quiet, Christ in danger,

Christ in hearts of all that love me,

Christ in mouth of friend and stranger.'

Lifted up high

Patrick placed trustful reliance on the creed, and experienced numerous dreams and visions sent by God.

In one vision Patrick saw himself portrayed as a lifeless stone. The Almighty took hold of the stone of Patrick, lifted him from the mud, and set him on top of the wall.

The inference was clear; what was slave and seen as of low consequence was about to be made leader; to be lifted to a position of pivotal importance in God's Holy Service.

Escape from Captivity

One night, in his sleep, Patrick heard a voice saying to him,

'It is well that you fast, soon you will go to your own country.'

Again, after a short while, he heard a voice saying, 'See, your ship is ready'.

In obedience to this heavenly message, Patrick made a break for freedom.

After six years of slavery, he started on the two hundred mile journey to the east coast.

When Patrick arrived at the ship which had been foretold, it had already raised anchor for sail.

The crew - initially reluctant to take him on as passenger - eventually relented.

They set sail with Patrick safely on board.

After three days at sea, all disembarked on the opposite shore.

It is uncertain whether they landed in Britain or France.

Homecoming and Priesthood

From there Patrick made his way home again, where his parents gave him warm welcome.

Despite his joyous return, this young man - susceptible to dreams, visions and the moods they bring - was not the same young lad who had been abducted.

His whole outlook had changed, and he now tended towards the Church.

Patrick underwent Church training near his home in Britain.

It is probable he received further training in a Gaul Monastery in preparation for ordination.

It is thought that Patrick received guidance from Germanus, Bishop of Auxerre in France.

Trial by friendship

Patrick was broken hearted when a close friend betrayed his confidence.

He had confided a past life difficulty to this person who then took the opportunity to shame him publicly.

This affected Patrick's position in the Church, and the experience affected him greatly.

God Himself comforted the mortified and betrayed Patrick.

This He did by means of prophetic dream.

The dream proved fortuitous for Patrick, who had been left deeply shaken by the recent events.

His confidence had been affected by his embarrassment and inner sufferings.

In the dream, Patrick saw his own face on a coin. The head of Roman emperors were often engraved on coins with words of honor and priase inscribed in letters around the head.

In Patrick's dream, the words surrounding his head were words of disgrace and shame.

Then he heard God's Voice, saying, 'We have seen with displeasure the face of Deisignatus.'

God disapproved of the words which attempted to tarnish Patrick's reputation.

Patrick arose from the dream, comforted and resolved.

Call to Ireland

Patrick felt called to return to Ireland after a prophetic dream.

In this dream-vision, he saw a man called Victoricus standing in front of him.

In his hand he held a countless letters.

Victoricus gave Patrick one of them, and he read the opening words of the letter, which were 'The voice of the Irish'. [4]

At the same moment he read the beginning of the letter, he thought he heard their voices - they were those beside the Wood of Voclut, which is near the Western Sea - and they cried out as one,

'We ask thee, boy, come and walk among us once more.'

A series of dreams and visions prepared Patrick for his great task ahead; they contained warnings and encouragement for the difficult task that lay ahead.

It turned out to be no less than the evangelisation of an entire nation.

Patrick was commissioned as a bishop to serve in Ireland; and set sail back to the very land he had fled before.

Ministry in Ireland

Patrick wasted no time once back on Irish soil.

He tramped all over Ireland, serving as Bishop.

Patrick preached the Word of God, baptized the people into Christianity and celebrated the sacraments.

It is said among the local people in Dublin that Patrick used to wade through a ford near the River Liffey - [the ford no longer extant] - in order to reach the higher hill area where the present day Church of St Audoen stands. [5]

One day as he was wending his way up the hill Patrick stopped, leaned on his staff and looked over the whole wooded area.

It was apparent he had just seen a vision, and he declared that where there was just ford, wood and settlements,

"One day there will rise a magnificent city, as far as the eye can see."

That prophecy came true; the extended city of Dublin lies in that very area, as far as the eye can reach and further.

Many pilgrims still walk in the footsteps of Saint Patrick.

From the present day Church of St Audoen, it is a short walk to where countless Irish were baptised by the great Saint.

Patrick baptized royalty and villagers, kings and shepherders alike.

Well of Saint Patrick

The well of Saint Patrick - no longer extant, but commemorated down the centuries and marked by a plaque in the grounds of Saint Patrick's Cathedral Dublin - was the site of the mass baptisms.

In 1901 building works beside the Cathedral unearthed six Celtic grave slabs. These were subsequently dated to the 10th century.

One of these large stones covered the remains of what looked like an ancient well.

It is possible that this is the same well which Saint Patrick used in the fifth century.

The presence of the stones [still to be viewed in the Cathedral] prove that the site has been in use for at least one thousand years.

The first record of there being a building was in 890 AD when Gregory, King of Scotland, visited a church.

The decision to build a church there was probably based upon the close connection with the Saint.

In 1190 the site was chosen by Archbishop John Comyn to be raised to Cathedral status and eventually the wooden church was replaced with the great structure which can be viewed today. [6]

Confession

More than fifteen hundred years ago Saint Patrick wrote a Letter in Latin.

At a later stage he authored a personal account of his work as a bishop of Ireland, called his Confession.

The Confession and the Letter to the soldiers under the command of Chieftain Coroticus are recognized as authentically the work of Patrick.

Written in the 9th century, The Book of Armagh contains accounts of St Patrick's life, a copy of St Patrick's own Confessio, as well as a complete New Testament.

It was written by the monk, Ferdomnach, who died in 846 AD.

According to this book, Patrick asked the local chieftain for a site on which to build his church.

The chieftain, Daire, refused Patrick the site he requested.

He gave him instead the place now called 'St Patrick's Fold' or 'Ferta Martyrum', in the present Scotch Street. [7]

PilgrimagesAs Patrick baptized the Irish people into Christianity, he nurtured their faith as well.

Some 30 000 Irish, among them some elderly and ailing, left Ireland assisted by Patrick.

He gave his permission and benediction for their pilgrimages.

One group set off for the Holy Land, Jerusalem their destination.

A second group left for the pilgrimage destination of Rome.

A third group left to visit the graves of the Apostles, including that of beatissimus Jacobus in Compostela.

Christian pilgrimage thereafter became ever more popular.

Foundations of pilgrims' hostels in Dublin in 1216 and Drogheda - where St James' Street and St James' Gate still evoke the original dedication- testify to the massive numbers of pellegrini among the Irish through the centuries.

In October 1996 more than thirty burials were discovered during archeological rescue excavation in Mullingar, County Westmeath.

Two of them contained scallop shells - proof of pilgrimage in honor of Saint James.

Ten years earlier, similar finds of scallop shells had been made during excavations of Saint Mary's Cathedral, Tuam, County Galway.

They were also of thirteenth to fourteenth century origin.

In recent times, further shell-associated burial sites have been found during excavation of the Augustinian Friary at Galway.

In 1992, a pewter scallop shell was discovered underneath the wall of a late medieval tomb at Ardfert Cathedral.

Mounted within the shell was a little bronze-gilded figure of St James.

This shell is a pilgrim badge. The emblem of the shell has always been connected with the Apostle James.

The occurrence of the shell at a burial site indicates that the deceased had been a pilgrim to the grave of the Apostle in Santiago de Compostela in Northern Spain. [8]

Missionary expeditions

During his missionary expeditions, it is believed that Patrick sailed through Strangford Lough, [9]

to land just outside the town of Downpatrick. [10]

In 432 AD Patrick established his first church in a simple barn.

This church became known as Saul Church.

Two miles outside Downpatrick, a replica of this first church stands today. [11]

Close by, on the crest of Slieve Patrick, is a huge statue of the saint.

Bronze panels illustrate scenes from the life of Ireland's patron saint.

Armagh is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland; Patrick called the city 'my sweet hill' and founded his first large stone church here in 445 AD.

Armagh's two Cathedrals are dedicated to him. The Armagh County Museum, the Armagh County Library and No. 5 Vicar's Hill hold material highlighting the city's role in the history of Christian Ireland. [12]

Patrick called his ministry 'hunting and fishing'. He spiritually hunted after people in the Name of Christ, fishing patiently among them to help them

Patrick unfortunately experienced enslavement a second time.

After word from God, he found his freedom again - doubtless traumatized by the repeated experience.

Pascal fire at Slane

Patrick had taken as his mission the spread of Christianity across Ireland.

When he returned to Ireland after becoming a priest, there would already have been converts to the new faith with Palladius as their Bishop.

Small groups of Christians in rural Ireland had naturally evolved into autonomous communities - a monastic system.

Patrick founded many churches, each time leaving them in the care of a trusted follower.

Trailblazer

Patrick blazed his trail through Ireland. He made his mark on the Rock of Cashel.

The Rock of Cashel was the traditional seat of the Kings of Munster for several hundred years.

Cashel is reputed to be the site of the conversion of the King of Munster by St Patrick in the 5th century. [13]

Croagh Patrick - a high mountain and an important site of pilgrimage in Co Mayo in Ireland - was the site where Patrick fasted and prayed to God for forty days and nights.

Croagh Patrick thereafter became the focus of Christian pilgrimages after Patrick, and is a popular site of pilgrimage to this day. [14] and [15]

Croagh Patrick had originally been a site for pagan pilgrimage; now redirected by Patrick in the service of God.

Patrick is said to have confronted the Corra, or serpent goddess, the symbol of pagan power, at Lough Derg in Donegal.

Thus Patrick faced the powers of darkness symbolised by the serpent goddess, at this venue - and triumphed. [16]

St Patrick's Chair and Well can be found about 5 miles out of Aughnaclay. This is Altadaven on the north eastern flank of Slieve Beagh. Its name means 'the cliff of demons'. St Patrick's chair is a massive and well worn stone in the shape of a seat with a back rest, a seat of dimensions more suited to a giant than a saint.

The chair sits on a high ridge surrounded by other enormous boulder stones, with a number of cup marks on the stones.

According to local tradition, Patrick was passing this way as he journeyed from Clogher to Armagh, when he came upon a pagan rite being performed at the site.

Instead of destroying the rock as he did at Killycluggin, he merely banished the pagan spirits to a nearby lake.

He then preached from the chair, and baptised people with water from the rock area.

This is the Well of Lughnasa, one of the famous wells of St Patrick. [17]

The Killycluggin Stone can be found by a right turn to Bawnboy.

This replica is a marker. The original is in Cavan County Museum in Ballyjamesduff and is an Iron Age ritual stone, a rounde boulder.

The stone is about 5 feet tall, elaborately decorated with closely coiled spirals interconnect with La Tene style patterns.

The top was damaged by St Patrick during his confrontation with Crom Dubh at Killycluggin.

The stone stood at one time outside the stone circle in Killycluggin and was decorated all over with gold.

It represented the god Crom Cruach, or Crom Dubh who is the dark god, the 'bent one' who received the 'first fruits' at Lughnasa or harvest in the form of the corn maiden.

The ritual or sacrifice of the girl was held to ensure the continuing fertility of the earth.

When Patrick travelled this way, he smashed the pillar stone and overturned the stones of the circle in an attempt to destroy the powerful hold this dark entity [satan] had on the people.

The Hill of Tara

Patrick also focused his attention on places of power. He challenged the High King at Tara when he lit the pascal fire at Slane.

The distance from the Hill of Tara to Slane is 23 kilometers.

There was good reason for Patrick's actions. According to the religion of the druids, fires were forbidden on the eve of the Spring Festival.

The Hill of Tara, known as Temair in gaeilge, was the seat of ancient power in Ireland.

142 kings are said to have reigned there in prehistoric and historic times.

Temair was considered the sacred place of dwelling of dwelling for the pagan gods, and was the entrance to the otherworld.

By lighting the Fire of Christ on the Eve of the Christian Festival, Patrick was proclaiming the God's Kingship above the power of the Irish Kings and their religion.

Patrick came to Temair to confront the ancient religion of the pagans at its most powerful site. [18]

When Patrick lit the fire of the Easter Vigil at Slane, the druids predicted the fire would destroy Tara.

They were correct; the ancient religion went into decline, in correlation with the spread of Christianity across the country.

It must be remembered, too, that the fire on Tara was lit in view of the slave holdings.

Patrick's defiant claiming of Christianity was also a message to the captives; according to the Gospel, they would eventually be set free not only from sin, but from their fetters.

As, indeed, history proved. The slave markets of Dublin are no more.

Letter to Coroticus

Patrick challenged many. He wrote an open letter to chieftain-king Coroticus in southern Scotland.

This man had enslaved some of Patrick's newly confirmed Christians, murdered a number of them, mistreated the evangelized, and sold from their number.

Patrick tried to buy back the captives without success.

He suffered deeply as he thought about the Christians now suffering so deeply.

He wrote a letter to Coroticus which was searing in its condemnation of the actions of the chieftain-king and his followers.

Fulfilment of Patrick's life

Patrick was an inspiration during his lifetime.

Patrick is a continued inspiration today, and deeply beloved in Ireland.

Eventually Patrick went home to God, leaving his earthly body - his outer coat, as it were - in his beloved Ireland.

Patrick's body lies in Downpatrick graveyard, on the grounds of the Cathedral.

His resting place is marked by a flat boulder stone. [19]

This man - youth, son, slave, priest, bishop, maligned, missionary - ranged the land of Ireland and claimed it for God.

It is fitting that today - in every town and city in Ireland, and every year on a special Feast Day - the people of Ireland reclaim him as their Holy Patron Saint.

[1] Meehan, Cary. The Traveller's Guide to Sacred Ireland. 2002. Gothic Image Publications; England

[2] Slemish Mountain

http://www.ireland.com/en-us/what-is-available/destinations/northern-ireland/county-antrim/ballymena/all/2-1727/

[3] Cagney, Mary. Patrick the Saint.

www. christiantoday. com/history / issues/ issue-60/patrick-saint. html

[4] The Confession of Saint Patrick

http://www.catholicplanet.com/ebooks/Confession-of-St-Patrick.pdf

[5] St Audoen's Church, Dublin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Audoen%27s_Church,_Dublin_(Church_of_Ireland)

[6] St Patrick and the Cathedral

https://www.stpatrickscathedral.ie/saint-patrick-and-the-cathedral/

[7] Meehan, Cary. The Traveller's Guide to Sacred Ireland, Page 48. 2002. Gothic Image Publications; England

[8] http:// www. historyireland.com/ medieval-hitory -pre-1500/the- irish-medieval-pilgrimage-to-santiago-de-compostal/

[9] Strangford Lough Lookout

http://www.ireland.com/en-us/what-is-available/attractions-built-heritage/nature-and-wildlife-attractions/destinations/northern-ireland/county-down/newtownards/all/2-26010/

[10] Downpatrick

http://www.ireland.com/en-us/destinations/northern-ireland/county-down/downpatrick/all/2-14077/

[11] Saul Church

http://www.ireland.com/en-us/what-is-available/attractions-built-heritage/churches-abbeys-and-monasteries/destinations/northern-ireland/county-down/all/2-3387/

[12] Armagh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/County_Armagh

[13] Rock of Cashel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_of_Cashel

[14] Meehan, Cary. The Traveller's Guide to Sacred Ireland, Page 25. 2002. Gothic Image Publications; England

[15] Teach na Miasa, Croagh Patrick Visitor Center at the Foot of the Holy Mountain.

www. croagh-patrick. com

[16] Meehan, Cary. The Traveller's Guide to Sacred Ireland, Page 40. 2002. Gothic Image Publications; England

[17] Meehan, Cary. The Traveller's Guide to Sacred Ireland, Pages 143 to 144. 2002. Gothic Image Publications; England

[18] Tara - Temail

http://www.mythicalireland.com/ancientsites/tara/

[19] Down Cathedral and Saint Patrick's Grave

http://www.ireland.com/en-us/what-is-available/attractions-built-heritage/churches-abbeys-and-monasteries/destinations/northern-ireland/county-down/downpatrick/all/2-3000/

The True Story of Saint Patrick

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZTYQyv8e-x4

The Saint Patrick Centre

http://www.ireland.com/en-us/what-is-available/attractions-built-heritage/museums-and-attractions/destinations/northern-ireland/county-down/downpatrick/all/2-3359/

Resource;

Simms, George Otto. 2004. Saint Patrick, Ireland's Patron Saitn. The O'Brien Press; Dublin.

With thanks to ireland.com, catholicplanet.com, wikipedia.org, stpatrickscathedral.ie, Ireland.com, mythicalireland.com, youtube

0 notes

Text

Trusty’s Hill: royal site and Pictish symbols

According to the article the site of Trusty’s Hill was the royal stronghold of the kingdom of Dalriada. The existence of Pictish carvings at the site and a rock cut basin that most likely was used for anointing kings indicates that it was a royal site. Pictish carvings were found at other known royal sites such as Edinburgh Castle so they have a connection to the ruling class in the early Middle Ages. The carvings date to the 8th or 9th century after the fort was destroyed and unoccupied according to the archaeologists who excavated the site. Archaeologist Chris Bowles noted that “if they were executed after its abandonment, this would testify to the site’s endurance in local memory” (Weiss, 36). I like to think that the common people who lived around the site viewed it with importance. They may have longed for a time when there was some kind of royal power that kept order or made the area safe from raiders. In a way this relates to Amon Sul or Weathertop from LOTR because people still had a connection to the time when there was a strong kingdom of men in power that kept order. Trusty’s Hill seems to be similar to Weathertop in that way.

0 notes

Text

DNA shows Irish people have more complex origins

“The blood in Irish veins is Celtic, right? Well, not exactly. Although the history many Irish people were taught at school is the history of the Irish as a Celtic race, the truth is much more complicated, and much more interesting than that...

Research done into the DNA of Irish males has shown that the old Anthropological attempts to define 'Irish' have been misguided. As late as the 1950s researchers were busy collecting data among Irish people such as hair colour and height, in order to categorise them as a 'race' and define them as different to the British. In fact British and Irish people are closely related in their ancestry.

Research into Irish DNA and ancestry has revealed close links with Scotland stretching back to before the Ulster Planation of the early 1600s. But the closest relatives to the Irish in DNA terms are actually from somewhere else entirely!

Irish Blood: origins of DNA

The earliest settlers came to Ireland around 10,000 years ago, in Stone Age times. There are still remnants of their presence scatter across the island. Mountsandel in Coleraine in the North of Ireland is the oldest known site of settlement in Ireland - remains of woven huts, stone tools and food such as berries and hazelnuts were discovered at the site in 1972.

But where did the early Irish come from? For a long time the myth of Irish history has been that the Irish are Celts. Many people still refer to Irish, Scottish and Welsh as Celtic culture - and the assumtion has been that they were Celts who migrated from central Europe around 500BCE. Keltoi was the name given by the Ancient Greeks to a 'barbaric' (in their eyes) people who lived to the north of them in central Europe. While early Irish art shows some similarities of style to central European art of the Keltoi, historians have also recognised many significant differences between the two cultures.

The latest research into Irish DNA has confirmed that the early inhabitants of Ireland were not directly descended from the Keltoi of central Europe. In fact the closest genetic relatives of the Irish in Europe are to be found in the north of Spain in the region known as the Basque Country. These same ancestors are shared to an extent with the people of Britain - especially the Scottish.

DNA testing through the male Y chromosome has shown that Irish males have the highest incidence of the haplogroup 1 gene in Europe. While other parts of Europe have integrated continuous waves of new settlers from Asia, Ireland's remote geographical position has meant that the Irish gene-pool has been less susceptible to change. The same genes have been passed down from parents to children for thousands of years.

This is mirrored in genetic studies which have compared DNA analysis with Irish surnames. Many surnames in Irish are Gaelic surnames, suggesting that the holder of the surname is a descendant of people who lived in Ireland long before the English conquests of the Middle Ages. Men with Gaelic surnames, showed the highest incidences of Haplogroup 1 (or Rb1) gene. This means that those Irish whose ancestors pre-date English conquest of the island are direct descendants of early stone age settlers who migrated from Spain.

Irish origin myths confirmed by modern scientific evidence

One of the oldest texts composed in Ireland is the Leabhar Gabhla, the Book of Invasions. It tells a semi-mythical history of the waves of people who settled in Ireland in earliest time. It says the first settlers to arrive in Ireland were a small dark race called the Fir Bolg, followed by a magical super-race called the Tuatha de Danaan (the people of the goddess Dana).

Most interestingly, the book says that the group which then came to Ireland and fully established itself as rulers of the island were the Milesians - the sons of Mil, the soldier from Spain. Modern DNA research has actually confirmed that the Irish are close genetic relatives of the people of northern Spain.

While it might seem strange that Ireland was populated from Spain rather than Britain or France, it is worth remembering that in ancient times the sea was one of the fastest and easiest ways to travel. When the land was covered in thick forest, coastal settlements were common and people travelled around the seaboard of Europe quite freely.

I live in Northern Ireland and in this small country the differences between the Irish and the British can still seem very important. Blood has been spilt over the question of national identity.

However, the latest research into both British and Irish DNA suggests that people on the two islands have much genetically in common. Males in both islands have a strong predominance of Haplogroup 1 gene, meaning that most of us in the British Isles are descended from the same Spanish stone age settlers.

The main difference is the degree to which later migrations of people to the islands affected the population's DNA. Parts of Ireland (most notably the western seaboard) have been almost untouched by outside genetic influence since hunter-gatherer times. Men there with traditional Irish surnames have the highest incidence of the Haplogroup 1 gene - over 99%.

At the same time London, for example, has been a multi-ethnic city for hundreds of years. Furthermore, England has seen more arrivals of new people from Europe - Anglo-Saxons and Normans - than Ireland. Therefore while the earliest English ancestors were very similar in DNA and culture to the tribes of Ireland, later arrivals to England have created more diversity between the two groups.

Irish and Scottish people share very similar DNA. The obvious similarities of culture, pale skin, tendency to red hair have historically been prescribed to the two people's sharing a common celtic ancestry. Actually it now seems much more likely that the similarity results from the movement of people from the north of Ireland into Scotland in the centuries 400 - 800 AD. At this time the kingdom of Dalriada, based near Ballymoney in County Antrim extended far into Scotland. The Irish invaders brought Gaelic language and culture, and they also brought their genes.

Irish Characteristics and DNA

The MC1R gene has been identified by researchers as the gene responsible for red hair as well as the accompanying fair skin and tendency towards freckles. According to recent research, genes for red hair first appeared in human beings about 40,000 to 50,000 years ago.

These genes were then brought to the British Isles by the original settlers, men and women who would have been relatively tall, with little body fat, athletic, fair-skinned and who would have had red hair. So red-heads may well be descended from the earliest ancestors of the Irish and British.”

by Marie McKeown

(source)

338 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bellaghy tour company lands starring role in new TV travel show

Bellaghy tour company lands starring role in new TV travel show

Viewers will enjoy segments on the history of the ancient Irish Kingdom of Dalriada, including a trip to historic Glenarm Castle. The waterfalls of … social experiment by Livio Acerbo #greengroundit #travel #tours

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

This stream of consciousness inspired by HistoriaBrittanorum’s Battle 8, the Battle of Caer Guinnion/the White Fortress. It could be the Fort of the Legions as well, but York’s Latin-Brythonic Name of Eboracum, actually shares a root with the Latin of Ivory (eburone,or something??...Ivory has a sense of Whitish—maybe York’s Walls, repaired by Constantine, appeared white when viewed from a distance??), along with other speculations of meaning (its British/Welsh form of Efrauc mimics the AngloSaxon ‘Eofor’ which means Boar...not related, I don’t think, unless the Boar was the standard of the VI Legion Victorius, stationed in York, but that might have been a bull actually??). The boar belonged to one of Britannia’s other legions, I think.

Anyway, Nennius writes that it was this Battle in which Arthur bore the Image of the Virgin on his shield/suspended across his shoulder...like a shield.

In Welsh ballad tradition, Arthur’s shield is translated as ‘The Face of the Evening’. This was a common epithet given to the Virgin Mary, But was actually a phrase directly acquired from Venus-Aphrodite, as the planet Venus appearing with the Sun and Moon as the Morning Star and Evening Star. Venus, of course, was the Babylonian-Sumerian Ishtar/Inanna. The Queen of Heaven, literally, and...another epithet of the Virgin Mary. Celestial Brigantia was another appelative for the same goddess, as understood by the Romano-British. A tutelary goddess of what had been the most influential tribe of northern Britain, even after Roman occupation, through the 3rd c AD at least. And dedications to ‘The Virgin’, meaning ‘Virgo/the Constellation’, alluded to her archaic Sumerian origins as the great Creatrix of Life/Death/Learning/Science/Poetry/Music/Agriculture/Law/Civilzation/War/Medicine/Justice/etc...all the aspects embodied historically by Inanna, the Face of the Evening, who becomes Freya-Frigg-Skathi-Nanna-Hella in the Nordic pantheon.

Anyway, Arthur, Uthyr in my take, when it’s mentioned by Nennius he bears the Face of the Virgin into battle, ACTUALLY harkens to a pre-Christian concept, molded to Christian tastes, of the Archaic Virgin. IDK if that was Nennius’s intent, or if Geoffrey of Monmouth understood that context when he compiled his epic 300 years later. Maybe he did. After all, it’s Geoffrey who conceived of Morgan le Fey/of the Faery, as the most learned in medicine, math, and astronomy, of her 9 Muse-like Sisters, who resurrect not just the Muses, but 9 Gallic priestesses who resided upon Sena, off the coast of Brittany, known as the Gallicenae. And, Geoffrey liked his Queens. He had no problem writing powerful women into his epic. After all, it’s from Geoffrey Shakespeare drew his inspiration for Cymbeline and King Lear/Cordelia. Anyway, the motifs of the Arthurian codex, resound from (my own speculation) a much earlier, borrowed concept lying somewhere between Inanna, and Athena’s aegis of the Gorgon (Medusa, being an aspect of Athena actually, and Andromeda as well. The name alone of Andromeda, means, in simplistic breakdown, ‘Ruler of Men’. And the symbolism when she’s chained to the rocks before the Sea-monster, Cetus, mirrors Inanna in the Underworld, having passed the 7 Gates of Hell, stripped of her Status, judged and condemned by her Sister, Ereshkigal, to be hung by chains, and tortured into death for her arrogance in daring to conquer the Land of the Dead). I love how unsentimental these first Sumerian myths were before they became softened by later Greek and Roman classical writers.

What Anglo-Norman Medieval authors borrowed in the term Virgin, has nothing to do with purity, or a woman with an intact hymen.

Virgins slept with men, or women whenever they wanted. The even had children, with or without a male progenitor. The oldest sense of the word ‘Virgin’ was an heroic woman. A woman complete into herself, who took on the traditional tasks of men, and women, w/o the assistance of a man. Or, like a Shield Maid, ALONGSIDE AND EQUAL with a man. Risking death, torture, rape, loss, or whatever else stood in her way (think Lagertha of Vikings), to triumph in the exact same conditions as their male counterparts. Sometimes with more ruthlessness, or more compassion, but human all the same, and judged by her actions before her gender/sex put a label on those actions. A Virgin has no bond with a husband, to whom she was subservient. That’s all the word meant.

Thus, Guinevere—The Face of the Evening, the Raven Queen, Ruler of Valentia Beyond the Walls, uniting the Picts and the Northern British houses under the Banner of Old Brigantia, to the aide of a southern prince, a son of Tyrants. Uthyr, bastard son of Vortigern, begotten in an act of humiliation upon Ygerna, the wife of Vortimer, Vortigern’s eldest son, dishonoring Vortimer for his rebellion against his father. In Uther’s veins runs the blood of Irish nobility (Ygerna comes from the tale of Ingren, the daughter of the Leinster King, Crimthann mac Ennais—here, as in Welsh geneolgies—Ingren/Ygerna is the daughter of Amlothi/Hamlet actually, a Danish Sea Raider who sleeps with one of 3 wives of Crimthann— and joins the Irish dynasties of the Deisi and the DalRiada to the British/Picti/Germanic families inhabiting the lands United from the Atlantic to the Irish Sea and North Sea and the Black Sea rim), Roman magistrates, and Waelsung heritage (Sigfrid, Sigmund, and Sinfjatli of Niebelung fame) that have shaped Uthyr as a son of Vortigern, rebelling against his father, and allied with Danish/Swedish/Geatish houses of Northmen, who have their own rivalries against fellow Danes/Swedes/Jutes/Saxons. Geoffrey’s Yder/Idris/Hidernus/Edern/Eurderyn—Eutharios/Eutigern—of the Black Danes, becomes my Uther, allied with Hrothgar/Swerta, an exiled Dane living amongst the Angles of NE Britain (This is based off Hrolf Kraki Saga. The Danish king of Beowulf, Hrothgar/Hroar...Rodger in English , who’s forever a battle-brother of Uther, in later decades. It was said Hrothgar converted to Christianity, and ruled his hall of Heort/sp?? as a Christian King). Uthyr, a quasi-outlaw, exiled bastard residing between Gaul, Scandinavia, and Byzantium in his youth, a mercenary andca Sea Wolf/Sea-Raider finally reuniting with his older brother, the renowned Vortimer/Riothamus/Embreis Wledig, to wrest back their authority to rule from their father, and the Jutish/Saxon houses opposed to the Danes/Geat/Angles.

Arthur comes later, as Guinever’s son, either—and both—by Uther and Theoderic the Great. Dynastic imperatives here span the transformation of Western and Northern Europe from Scandinavia to Ostrogothic Italy, and in-between. Guinevere, Uther, and Theoderic, encompass a strategy of this New World of civilizing Romanized Barabarians, amalgamations of Tribal cultures reviving old Roman precepts of rule and law, between Britannia on the Western end of Old Empire, to Ostrogothic Italy, that Theoderic seeks to establish as independent from Constantinople. Lying in their midst, a lion at the heart of Gallia, are the Franks, with Clovis clawing the Merovingian hold to sever Britannia, and Visigothic Spain, from Italy. Willing to ally with Byzantium to do so, in order to distract Theoderic into defending his eastern territories of the Adriatic, Clovis succeeds in driving the last of his Visigoth brethren out of Gaul, and the inception of the Kingdom of the Franks arrives like a tempest. And finds Uther slain with his long-time war-band on the fields of Poitier, in 507, and Arthagenes (a version of a title of Hercules/the Hindu-Hellenic-Persian Verethragna. The name resembles variations of Artogenes/Bear Kin or Bear Prince/Artius/Arthan/and Artogneu...from that hideous inscription, but in my mind, while not ‘King Arthur’, lends enough similarity to said names, I’m comfortable basing his persona, ultimately, off the mythic concept of Arkas/Arcas, the Bear Prince, who circles Polaris, son of the Bear Goddess/Artio-Artemis-Callisto, and the War-Lord/and the Guardian of the stars, Bootes and Draco), his son, or Throderic’s, serving in Theoderic’s forces, in the counter-campaign to win back southern Gaul from Clovis. Incidentally, one of Theoderic’s generals bears the name Ebba, or at times conflated as Eobba (like the Bernician king of the Anglo-Saxon king lists), as well as Ida—the first king of Anglians who defeats ‘Outigern’ (in my take, the son of Arthagenes, by a northern princess, Vivian/Nuvien—Nimue-which is Gaelicized as Bebhionn, and feeds into the renaming of Din Guardi as Bebenburg, after Ida marries the British princess, Beara, according to certain chroniclers of later era. Beara is my Nuvien, a British saint actually, and the name from which Vivian and Nimue derive, and Dutigern, her son, a form of Outecorigas, recorded on Celtic inscription from Dyfed, I think, as a Protector of the Region.) Where Ida accepts Outigern as a son, And so, at Din Guardi/Bamburgh in 547AD, Ida establishes the kingdom of Bernicia. That will, by his grandon’s time, unite under Aella of the Deirans, forming Northumbria. The Star of the North, and its emerging repository of Anglo-Celtic-Roman culture by 600-800AD.

This segment involves my revision of Theoderic’s daughter, Amalsuentha (a version of Melisande), actually being rescued from her assassination (she was strangled in a bath, around 534, by her cousin who coveted the throne of the Ostrogoths, which opened up Justinian’s excuse to invade Italy), as more of an comedic abduction by Offa/Yffi of the Deira/East Angles, Ida, and Cethegus, whose my version of the warrior-saint, Cathog/Cathomalos.

She becomes my version of Marcia—founder of Mercian law, as Geoffrey attributes Alfred the Great’s codex of law and rule procedure to a Marcia, a great queen of wisdom and courage, who...probably didn’t exist.

Anyway, I’ve now expounded to the point of random outline, and the tale which falls between my 2nd Century Artorius Castus Tale (that might go back to 1st Century Cartimandua, Agricola, and Arviragus/Genvissa, as mentioned by Geoffrey), and PreRev Paris with Jefferson and his Scottish lady physician.

As an underscore to the Uther/Guinevere tract of Gwen as Queen, and Defender of the North, later Uther’s Wife, and Theoderic’s lover, there’s this scene that comes from the Welsh Mabiniogion, of Culhwch and Olwen. The tale is basically a Welsh version of the Norse myth of Svipdag-Odr, and Menglod. Svips is cursed by his step-mother to only fall in love with a particular woman, who happens to be the daughter of a fearsome giant, and impossible to win. Unless the hero undergoes a series of impossible feats which he overcomes, of course, to finally win his bride, and kill her monster-father.

Anyway, there’s this passage Arthur speaks when his cousin, Culhwch arrives at Arthur’s hall, seeking some Band of Bros to help in his quest of Lady Love.

Basically, I’m a kow-tow to those ‘rules of hospitality’ we like to romanticize were inherent to tribal societies of Germanic and Teutonic origin, Arthur welcomes his cousin with every promise to provide him with anything he needs on his quest, except [paraphrased from rusty neurons]: “...my sword, my spear, my dagger, my ship, my shield, and...my Wife, Gwenhwyfar.”

Every time I come across this line, I think that’s either the coarsest of insults to his wife, and his queen, listed in an intinerary of his weapons. Or, it’s the most oblique of compliments to his wife. As Guinevere is his greatest weapon, even over his other enchanted implements, and won’t be utilized to any other man’s cause than his own. I’d like to add, that would be at her discretion of course.