#neocons

Text

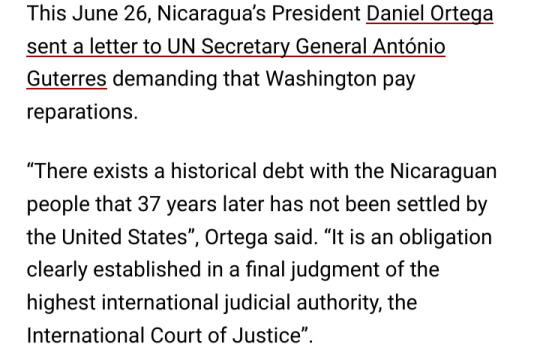

THE US STILL OWES NICARAGUA REPERATIONS SINCE 1986 ICJ DECISION

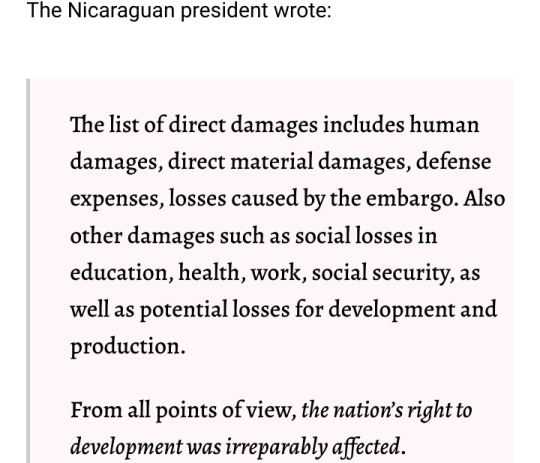

Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega has called on the United States to fulfill its obligations under International Law and to pay the $12 Billion in reparations owed to it under a 1986 International Court of Justice ruling.

The International Court of Justice is a UN sponsored platform to resolve international disputes between Nation-states.

This ICJ ruling was made in 1986 after years of the United States sponsoring a dirty war responsible for tens of thousands of Nicaraguan deaths, an attempted genocide against pro-Sandinista Nicaraguan civilians, the destruction of the country's Infrastructure and an economic blockade that thoroughly destroyed the Nicaraguan economy causing untold suffering among citizens.

In the 1986 ICJ ruling, the Judges wrote:

The United States in reality should owe reparations to countries all across the world for its horrific Imperialist Foreign Policy: Afghanistan, Iraq, Vietnam, Cambodia, Lao, Iran, Syria, Libya, Granada, the DPRK, Sri Lanka, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras and more.

#imperialism#us imperialism#western imperialism#us hegemony#neocons#neoliberalism#us wars#ICJ#international court of justice#UN#NATO#war news#news#us news#politics#us politics#politics news#socialism#communism#marxism leninism#socialist politics#socialist worker#socialist news#socialist#communist#marxism#marxist leninist#progressive politics#dirty war#nicaragua

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Usama Bin Lugee, Bush Jr, Little Dick Chaney, Rumsfeld and CONdoleezza Rice all in one room ??? The C.I.A claims this picture is fake, but what else would you expect the culprits to say ??

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think my dad is neoconservative in a way that makes him talk like a parody of other neocons. His reaction to Paul's arc in Dune Messiah was literally just "why is he so upset about committing genocide, he should learn to accept that that's part of being an empire."

#196#my thougts#neoliberalism#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#imperialism#neocons#neoconservatism#leftist#leftism#anti imperialism#colonialism#us imperialism#dune#dune messiah#paul atreides

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

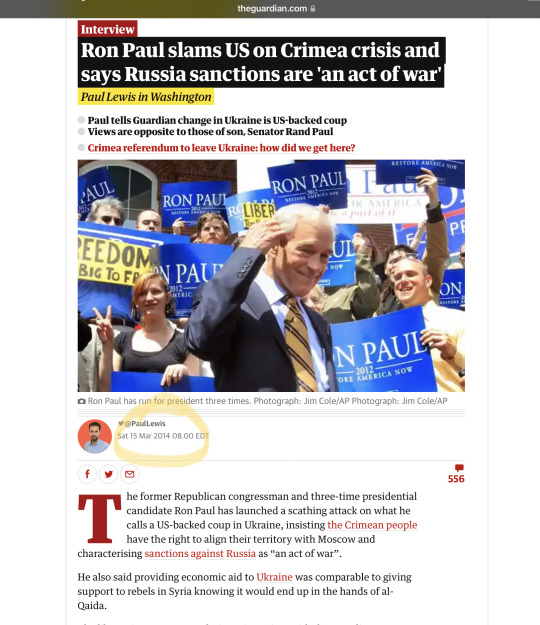

Trump is NOT CONSERVATIVE because he's anti-war. "The ex-VP intimated that the only conservative position, therefore, was a continuation of the war."-neocons

Earth to Mike Pence: Donald J. Trump has ALWAYS been anti-war, but you knew this when you agreed to be his running mate in 2016!

From The Pulse: Former Vice President Mike Pence has suggested that Donald Trump cannot make any promises to govern as a conservative if he is re-elected in the 2024 presidential election because the former President would implement a quick end to the war in Ukraine.

Pence claimed on CNN on Sunday that by ending the bloodshed between Russia and Ukraine, the 45th President would be “embracing the politics of appeasement on the world stage [and] walking away from our role as leader of the free world.”

“Look, the only way this war would end in a day, as my former running mate says, is if you let Vladimir Putin have what he wants, which, frankly, other candidates for the Republican nomination are advocating as well,” Pence continued, before describing Trump’s adoption of the same populism Pence himself embraced in 2016 as a growing threat.

Donald Trump announced his intention earlier this summer to bring about an end to the Ukrainian war within just 24 hours after re-entering the White House in January 2025, with the number of casualties on both sides continuing to grow. It is believed the Ukrainians have lost around 200,000 soldiers killed or wounded, and the Russians 300,000 similarly killed or wounded since the war began in February last year.

The former Vice President is not alone in fearing a swift peace if Trump were re-elected, as the former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson similarly implored the former President not to abandon the United States’ support for Ukraine.

#creepy mike pence#get trump#Mike Pence is a loser#Fake Christian Mike Pence#donald trump#trump 2024#anti war#neocons

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you live in or near the Long Beach, California area and are over the age of twenty-one, there is a free goth show at Alex's Bar tomorrow night

#goth#deathrock#free show#live music#Alex's Bar#Long Beach California#Shrouds#Clutter#Neocons#as in the band#not actual neocons#Disco Obscura#DJ Felix#DJ Night Creature

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

" I neocons si formano nella “Nuova Gerusalemme” della diaspora ebraica a New York City, la Lower East Side di Manhattan. Dallo shtetl alla Jewtown, dallo yiddish all’inglese, in un contesto bianco-anglosassone-protestante (Wasp) carico di veleni antisemiti, il passo è lungo. Fra i giovani figli o nipoti di immigrati si forma una esigua quanto ipercombattiva élite intellettuale marxista e filobolscevica che si batte per affermare il socialismo in America e nel mondo. Di quella New York si diceva fosse la città più interessante dell’Unione Sovietica*. Nel City College della metropoli gli squattrinati giovani destinati a formare la spina dorsale del neoconservatorismo a venire frequentano l’odorosa caffetteria studentesca occupandone l’Alcove 1, fortilizio dell’avanguardia trozkista in dissidio con la maggioranza stalinista, che governa l’Alcove 2. Durante la Guerra fredda, le origini ebraiche e comuniste di molti neocons li renderanno sospetti agli occhi di paleoconservatori e repubblicani mainstream anche dopo che il presunto tradimento sovietico dei loro ideali li avrà spinti verso un bellicoso anticomunismo associato al sostegno di principio per Israele, per niente scontato nell’America degli anni cinquanta. Dall’antistalinismo all’avversione totale per il comunismo, dalla contestazione all’adesione al sistema, contro le derive moderate e compromissorie di liberals e appeasers disposti al dialogo con i tiranni rossi, i neoconservatori già trozkisti faranno sentire la loro voce nel dibattito pubblico del dopoguerra.

Nell’accademia come nei media alternativi e nelle anticamere del potere, eminenti neocons quali Leo Strauss e Irving Kristol, Max Schachtman e Irving Howe, Richard Perle e Kenneth Adelman, fino a Douglas Feith e a Paul Wolfowitz, influente vicesegretario alla Difesa sotto George W. Bush, avranno modo di promuovere il globalismo democratico. Fine della storia. Mai come strutturata corrente politica o intellettuale, sempre al loro combattivo, lacerante modo. Il moto perpetuo della rivoluzione come fine in sé – comunista o anticomunista – impedisce di superare lo stadio delle connessione informali, esposte a litigi pubblici e odi privati, conversioni e apostasie. Fino al disastro iracheno, che nel primo decennio del secolo marca il tramonto del neoconservatorismo di governo. Non del movimento. In attesa della prossima alba. Perché in America profeti e crociati non muoiono mai. "

* Cfr. J. Heilbrunn, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons, New York-Toronto 2009, Anchor Books, p. 27.

---------

Lucio Caracciolo, La pace è finita. Così ricomincia la storia in Europa, Feltrinelli (collana Varia), novembre 2022. [Libro elettronico]

#letture#scritti saggistici#saggistica#saggi brevi#geopolitica#Lucio Caracciolo#leggere#citazioni#neocons#Leo Strauss#straussiani#New York City#Manhattan#diaspora ebraica#Stati Uniti d'America#trozkismo#Wasp#comunisti#anticomunismo#Israele#sionismo#secondo dopoguerra#Irving Kristol#Max Schachtman#Irving Howe#Richard Perle#Kenneth Adelman#Douglas Feith#Paul Wolfowitz#George W. Bush

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

If you would like to understand how we got here, listen to Professor Sachs. From Ukraine to Israel to Syria to Haiti, I kid you not. Jeffrey Sachs explains everything.

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Current events in the context of history

#oligarchy#Bandera#Nazi#neocons#Mosad#Ukraine#Israel#Malthus#population control#Christian Zionism#cults

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yeah, I think I'm gonna stay off social media as much as I can for the next... while.

Reaaaally don't want to see my 'friends' on here having emotionally charged irrational takes on the current conflict.

Just remember the Neocon playbook.

Netanyahu was FROTHING at the mouth for this to happen. Neocons have done this SAME SHIT for DECADES.

Create suffering -> Fascistic terrorist organization uses people's justified hatred & desperate circumstances to recruit -> More suffering -> More recruits, more anger, etc. -> Conveniently ignore warning signs of fascistic terrorist org planning large attack on your nation -> "New Pearl Harbor" -> Populous is traumatized, angry, easy to convince them terrorists are everywhere. Basically the same process the fascistic terrorist org used to recruit THEIR members! -> Congrats! Your nation is all fashied up and ready to do a genocide!

#neocons#hamas#israel#palestine#genocide#fuck neocons#fuck you if you think israel is justified in what they are about to do#fuck you if you think hamas is some kind of revolutionary org#neocons killed the socialist leaders in palestine#all of this is fuckign theatre to enable genocide#i am going to go cry now

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

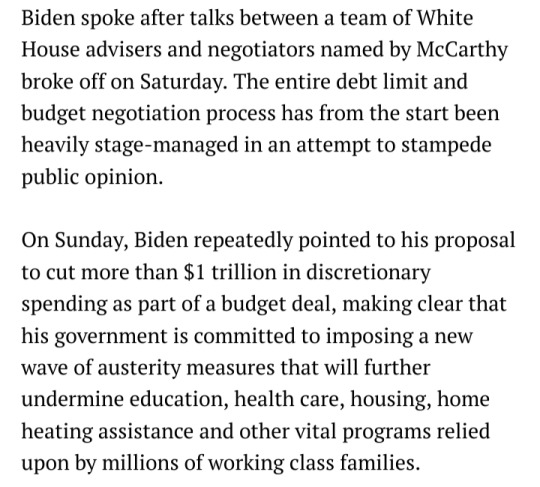

Biden proposes $1 trillion in social spending cuts after announcing $375 million more for war in Ukraine - World Socialist Web Site

I'm not a big fan of the Trots at WSWS, but when they're right, they're right.

Of course Biden never had any intention of protecting social spending in the US. He had two years to prioritize social spending, raise the minimum wage, he promised Paid Family Leave, sick leave, and swore he would expand Obamacare.

Of course he did nothing of the sort.

Biden has had decades in Congress and the Senate to prioritize Working Class people and has instead chosen to pursue an Imperialist Neocon agenda, sending nearly $170 BILLION for the Proxy-war in Ukraine.

But of course, Biden doesn't have a single extra $1 for the homelessness epidemic, healthcare, or any of the supposed Priorities he had when coming to office.

Biden's only interest is enriching the wealth of the Trans-Atlantic Capitalist Class.

#fuck biden#fuck capitalism#socialist news#socialist politics#socialist worker#socialism#communism#marxism leninism#socialist#communist#marxism#marxist leninist#progressive politics#politics#budget cuts#neoliberalism#fuck neoliberalism#biden is a neocon#neocons#news#us news#us politics

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

The neocons are really addicted to war. They want to invade Mexico because of fentanyl. I swear just when you think they learn their lesson they just change the targets.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In 1941, whether liberal societies could endure despite their weaknesses was a more than theoretical question. Strauss’s lecture addressed the long-standing question of how liberal societies might protect the virtues they need but often struggle to cultivate, and sometimes actively undermine. And his answer, offered in defense of what he called the “open society” (a term Karl Popper would put to different use four years later), was provocative. He argued that many virtues essential to liberalism are best understood in the moral traditions that are most opposed to liberalism. He also suggested that the vices most threatening to liberal societies are often nurtured by liberal ideals themselves. As was his style, Strauss suggested, rather than explicated, his thesis: An open society requires strengthening by moral and political imaginations that have been formed in closed societies.

Strauss’s lecture bore the solemn title “German Nihilism”—slightly misleading, since its focus was broader than Germany and deeper than nihilism. Strauss was horrified by National Socialism, and he closed his lecture by expressing his admiration for Churchill and his gratitude toward British combatants. But what most engaged his attention was not contemporary statesmen and soldiers, but a previous generation of teachers and students. Strauss worried that the mistakes made by progressive educators in the decades prior to the rise of National Socialism could be made again, endangering the stability of Western democracies.

Strauss opened with a claim that may be unsettling, even when considered in context. He expressed his regret that National Socialism had been identified with nihilism, a philosophical doctrine whose political goals were said to be purely destructive. His concern was not that Hitler’s regime had been denied a fair hearing among intellectuals. For Nazi ideology Strauss expressed only the severest contempt, and with the interesting exception of Ernst Jünger’s early work, he dignified no contemporary German writer with a citation. Nor did Strauss suggest that the regime’s goals were less barbaric in theory than they were proving to be in practice.

Strauss’s concern was that the brutality of the regime evoked strenuous moral responses that impaired philosophical thinking and historical judgment. The regime posed an obvious threat to its victims and to those resisting its advance on two continents by force of arms. But Strauss argued that it posed a less obvious and potentially more enduring threat to those opposing it by intellectual means. Authoritarianism clouded the thinking of some of its most trenchant opponents, making it difficult for them to understand critiques of modernity as anything other than the “ravings” of the vulgar, the provincial, and the stupid. Strauss lamented that a political movement whose lasting defeat required the deepest philosophical wisdom had, in too many cases, elicited something else. It had given defenders of democracy, among whom Strauss included himself, the opportunity to demonize liberalism’s critics as “gangsters,” “mentally diseased,” or “morbid.”

Strauss was not alone in wishing for a deeper understanding of the intellectual roots of European illiberalism. In the same semester, a young John Rawls published his first essay, a sympathetic reading of Oswald Spengler’s predictions of democratic decline. But Strauss’s worry was distinctive of him and his pedagogy, which would play an increasingly important role in American conservatism after his move to the University of Chicago in 1949. Strauss worried that Western thinkers were no longer capable of contemplating perspectives beyond liberalism, even against liberalism, from which to judge the present. Far from constituting a threat to clear thinking, such a perspective is essential to it—for only outside the open society can we identify its virtues and its vices, and gain the strength to endure its discontents. But if we are to reach this horizon, Strauss argued, a popular prejudice often directed against critics of liberalism must be rejected. For what is mislabeled “nihilism” is not a destructive doctrine at all. It is a protest on behalf of something of the highest human importance—something liberalism dismisses at its peril.

(…)

Strauss’s portrait of his classmates was unsparing, but not disdainful. Strauss described young men full of vehement certainty about what they rejected, but inarticulate and unreflective about what they affirmed. “The prospect of a pacified planet, without rulers and ruled,” he observed, “was positively horrifying to [them].” Strauss lamented that their passions found no outlet other than the crudest propaganda. Unable to understand or express themselves in any other way—Strauss noted that they had largely rejected Christian belief—they gave voice to savage forms of group identity. The mark of barbarism, Strauss explained, was the belief that truth and justice should be defined in terms of ethnic or racial membership.

But Strauss acknowledged that these students, shaped by defeat, conflict, and social disintegration, were inspired by an ideal—an ideal whose dangers they did not understand but whose allure they keenly felt. Here we approach the heart of Strauss’s lecture, which sought to place these interwar students and their ideal in a broader intellectual history. Strauss cautioned that he sought not to pardon what deserved condemnation, but to make intelligible what required understanding. He therefore challenged his class to see in the youthful German protest what many had failed to perceive two decades earlier: its moral basis. This protest against liberalism was not fundamentally inspired by a love of war or a love of nation, Strauss insisted. Nor could it be explained by material or class interests. It was inspired, as he put it in a bracing passage, by “a love of morality, a sense of responsibility for endangered morality.”

Strauss named this outlook the morality of the “closed society.” No sensitive reader of the lecture can avoid being struck by the intensity of the passages in which Strauss describes the gravity of the challenge this “endangered morality” poses to the “open society.” What is the closed society? Strauss didn’t identify it with any one people, tradition, or form of government. By the “closed society” he didn’t mean non-Western cultures, pre-Enlightenment thought, or even undemocratic polities. The closed society represented a perennial moral possibility, whose roots are found in every human soul and whose demands must be confronted by every human community. In its most common expression, the closed society levels a familiar accusation: that the open society is immoral, or at least amoral, because it jeopardizes the very possibility of living a virtuous life.

Strauss assumed his American students might have difficulty seeing the possible strengths, to say nothing of the seductive appeal, of a way of life associated with ignorance and bigotry. He therefore tried to show them how liberal and democratic ideals might appear from a perspective that denies their moral legitimacy—not out of resentment or bad faith, but out of loyalty to a higher order of values. The rights of man, the relief of the human estate, the happiness of the greatest possible number—for advocates of the open society, these are ideals that have inspired social progress. They are part of a shift in modern consciousness, through which we have recognized our power to change the present, rather than simply accept the authority of the past. But to defenders of the closed society, Strauss argued, the moral prestige of these slogans evinces a different kind of shift. It is a sign that humanity has been debased rather than ennobled.

To draw his listeners into anti-liberal ways of thinking, Strauss sketched the development of modern political thought from the perspective of the closed society. This interpretation casts the arc of modernity in a disturbing light, depicting as decline what Enlightenment thinkers hailed as advance. It sees modernity as the story of how and why Western societies chose to lower their moral ideals, exchanging the demanding codes of antiquity and biblical religion for the comfortable norms of commercial society, legal proceduralism, and bourgeois life. Heroic ideals, attainable only by the exceptional few, were defined down for the ordinary many; ideals that promoted spiritual or intellectual excellence were balanced by those promoting health and prosperity; ideals that imposed self-denial were replaced by those that indulged self-expression.

As Strauss’s reading of modernity suggests, the closed society is defined by what it affirms no less than by what it rejects. He emphasized that its conflict with the open society is ultimately over the most fundamental question: Which way of life is best for man? For defenders of the closed society, human life should be ordered to a political end whose achievement requires the highest and rarest human qualities. So demanding is its vision of moral excellence, so uncommon are the virtues it requires, and yet so necessary is it to the sustaining of human life, that its fulfillment involves the greatest personal risk. As Strauss described it:

Moral life . . . means serious life. Seriousness, and the ceremonial of seriousness . . . are the distinctive features of the closed society, of the society which by its very nature, is constantly confronted with, and basically oriented toward, the Ernstfall, the serious moment. . . . Only life in such a tense atmosphere, only a life which is based on constant awareness of the sacrifices to which it owes its existence, and of the necessity, the duty of sacrifice of life and all worldly goods, is truly human.

Duty, sacrifice, danger, struggle—here we enter the charged atmosphere of a moral world that Strauss feared his students, and not only his students, failed to understand. It saw the best human life as one that dares to risk all for the sake of heroic possibilities. It saw the desire to pledge oneself to a great cause and to prostrate oneself before great authorities as essential to human virtue. In later writings, Strauss would examine a tension between the life of philosophy and the life of faith, a tension that he believed was foundational to Western civilization. But the conflict between the open and closed societies is not a conflict between reason and revelation. It is a conflict over the necessity of life-and-death struggles for human excellence. If the open society is constituted by free argument and equal recognition, the closed society is formed by loyalty, courage, sacrifice, and honor. It celebrates the virtues that it believes make political order possible: the willingness to forgo material comforts, to close ranks against outsiders and oppose enemies, and, above all, to fight to the death with no thought for profit or pleasure. Though these virtues animate other spheres of life, they are, in their deepest origin and highest expression, martial virtues.

(…)

But in defending the martial virtues of courage, heroism, and loyalty, Strauss was not simply giving guarded expression to past political views. He was giving voice to a moral ideal that defenders of democracy were jeopardizing, at significant human cost. That ideal insisted that these are the virtues through which, and only through which, a man can prove himself to be a man in full. It contended that what makes us human is not the way we pursue and enjoy the goods of bodily life, however refined our habits might be. Rather, we prove our humanity only by exercising our radical ability to contradict those goods, only by risking our lives for a value greater than mere survival. To live as a human being is to fight to the death for something higher than life. Within this moral world—a world so fundamentally hostile to liberal modernity—man is not made for comfort and security. He is tempted by them. The man who wishes truly to live must flirt with death.

Strauss was aware of the destructive power of this impulse and its pursuit of meaning through confrontation with annihilation. But before it could be corrected, he believed, its moral critique of liberal modernity had to be confronted. Proponents of the closed society regard the open society as degrading not simply because it places bodily safety and well-being at its political center. They regard it as degrading because it diminishes the soul’s need for moral risk, demotes the virtues needed for pursuing and protecting the highest things, and devalues the men who strive to live by its severe code. For those, such as Ernst Jünger, who found the most sublime virtues in the trenches of a world war, the open society was hypocritical. It lived by achievements it did not properly honor, or merely pretended to honor, and in doing so lied about the basic facts of human experience. Its dream of a world of freedom and equality, a world in which everyone was happy and satisfied and at peace—such a world was no dream, but a posthuman nightmare, “in which no great heart could beat and no great soul could breathe.”

Strauss’s portrait of the closed society made no claim to originality. As he acknowledged, his account brought together critiques of liberal modernity made by Rousseau, Tocqueville, Nietzsche, and others, who had likewise questioned whether something vital to human life was lost when older moral codes were exchanged for greater freedom and equality. But if Strauss’s reading of history was not original, the lessons he drew from it for the American university were. As he brought his seminar to a close, he reflected again on the generation of students who had entered adulthood during the decades before the Second World War, and whose moral passions had been so poorly understood and so poorly formed. He said that what those students had needed most was “old-fashioned teachers.” It is a startling remark.

(…)

Strauss didn’t wish to turn his students into sophisticated enemies of liberalism. His goal was to turn them into virtuous defenders of democracy. But to become true patrons of the open society, they needed qualities of character that could be developed only through a proper appreciation of traditional society. The open society was right to order its common life through the exercise of reason and the arts of civility. But the closed society was also right about some important things. It acknowledged our need to be loyal to a particular people, to inherit a cultural tradition, to admire inequalities of achievement, to reverence the authority of the past, and to experience self-transcendence through self-sacrifice. It acknowledged as well the importance of a leadership class whose decisions expose them to special risk rather than shielding them from it. As Strauss observed, these are permanent truths, not atavisms, no matter how unpalatable they are to the progressive-minded. A society that cannot affirm them invites catastrophe, no less than does a society that cannot question them.

Strauss gave his lecture only months after the institution of a military draft in the United States. But his primary aim wasn’t to steel his students for the nation’s entry into war. As Western democracies sent young men into combat, they needed to think more soberly about the kind of society they wished to defend after the fighting ended. Strauss warned them against the illusion of building a culture around values of “openness” that scorned the human need for solidarity, sacrifice, and even suffering. As a philosopher, Strauss was a critic of modern thinkers whose ideas encouraged, as he later wrote, the “corrosion and destruction of the heritage of Western civilization.” Strauss was therefore both a defender of liberal democracy, as well as a critic of liberal theories of human nature that sought to domesticate the highest longings of the soul. He correctly saw that some of the most serious threats to liberal ways of life do not come from authoritarian regimes. They come from homegrown ideals of equality and freedom, which can exercise their own kind of tyranny over the social customs and habits that make open societies possible.

For Strauss, more was at stake than the West’s readiness to shed “blood, sweat, and tears” on the shores of Europe and the islands of the South Pacific. There was also the tradition of education on which the peoples of the West depend for their civilizational identity. Strauss saw liberal education not as a catechesis in liberal pieties, but as a courageous engagement with moral traditions that may be profoundly at odds with democratic life. In this way, a genuinely liberal education served as a “counterforce” to the leveling pressures of mass culture. It provided reminders, as he later put it, of human greatness, of human possibilities beyond a life of consumption and production.

Strauss wrote frequently about education, and the survival of great books education in our country owes a great deal to his work. But his boldest insight is found in this early lecture, delivered at a time when the future of Western civilization was in doubt. Strauss implied a moral connection between the martial virtues of the closed society and the liberal virtues of the open society—between the life of the warrior and the life of the philosopher. He suggested that only in the search for wisdom could a human being truly achieve the qualities sought by the warrior and the soldier. Strauss did not therefore condemn the man who fights valiantly to the death; he sought to perfect the martial ideal, transposing it to the mind’s struggle against its enemies, falsehood and flattery. To pursue the highest truths and the highest goods, he claimed, requires the rarest human excellences. It requires the courage to risk cherished beliefs and self-images in encounters with great authors of the past. Strauss ended his lecture with a remark that is as arresting today as it was eighty years ago. He observed that there is a place in Western culture where the old morality and its noble ideals are still defended rather than subverted. Within its ancient universities, the greatest human battle is carried on bloodlessly and perpetually—as rational debate over the nature of truth and goodness.

(…)

Strauss wished to recover classical philosophy and revive the careful study of the great books. He believed that this kind of education could open the aristocratic horizon that citizens of an open society most desperately need, if they wish to save liberalism from itself: not freedom from the past, but freedom from the present. Perhaps education cannot bear the moral weight that Strauss placed on it. And as religious men and women, we should entertain even more serious doubts whether the philosophical life can fulfill our deepest aspirations for wisdom and holiness. But as our politics burns through the ideological firewalls of the postwar era, we should heed Strauss’s prescient warning: An education that denies our need to risk our lives for something beyond life will fail students to the extent that it succeeds. It will leave them in a condition like that of Strauss’s doomed classmates: angry, lost, and prey to the savagery that will destroy our civilization.”

#strauss#leo strauss#liberalism#anti liberalism#open society#closed society#nihilism#germany#philosophy#political philosophy#education#ernst junger#ernst jünger#modernity#tradition#society#neocons#neoconservative

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jimmy Dore says "I told you"

youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

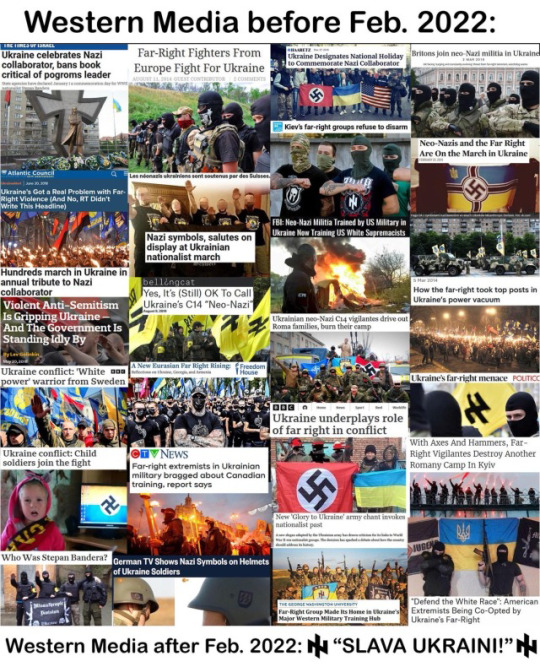

It all started with Putin’s 2007 Munich speech against the New World Order…

https://www.cato.org/commentary/did-putins-2007-munich-speech-predict-ukraine-crisis

…

“However one might embellish this term, at the end of the day it refers to one type of situation, namely one centre of authority, one centre of force, one centre of decision‐making. It is a world in which there is one master, one sovereign.”

“Today we are witnessing an almost uncontained hyper use of force — military force — in international relations, force that is plunging the world into an abyss of permanent conflicts. And of course, this is extremely dangerous. It results in the fact that no one feels safe. I want to emphasise this — no one feels safe!”

“NATO has put its frontline forces on our borders, although as yet, we do not react to these actions at all. NATO expansion, he stated, represents a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust. And we have the right to ask: against whom is this expansion intended? And what happened to the assurances our western partners made after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact?”

“With respect to democracy and NATO expansion. NATO is not a universal organisation, as opposed to the UN. It is first and foremost a military and political alliance, military and political!”

“Moreover, his concerns and objections went beyond the mere expansion of NATO’s membership. His larger sus “why is it necessary to put military infrastructure on our borders during this expansion?”

https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/02/18/putin-speech-wake-up-call-post-cold-war-order-liberal-2007-00009918

…

.

2008: Russia-Georgia conflict after Georgia invades South Ossetia

https://www.history.com/news/russia-georgia-war-military-nato

…

2014:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russo-Ukrainian_War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annexation_of_Crimea_by_the_Russian_Federation

…

2015:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_military_intervention_in_the_Syrian_civil_war

…

>>>

2017: Russia defeats ISIS

https://www.cnbc.com/2017/12/11/putin-boasts-about-defeated-isis-in-syria-discloses-troop-withdrawal.html

…

2022: Putin: Denazification of Ukraine

#syria#tartus#isis#Georgia#ukraine#crimea#grozny#south ossetia#Donbas#baghdadi#israel#john mccain#team b#neocons#denazification#putin

22 notes

·

View notes