#the character growth and development and becoming more well rounded people through world travel was my favorite part of the show!

Text

I'll be honest, if their idea of improving on the original ATLA is to remove the character traits the characters overcame within the narrative as part of their growth because they paint the characters in a bad light or whatever, I don't think they know the show well enough to be remaking it. What next? Are they gonna erase Iroh's military history because good people can't have ever made the wrong choice in their lives? Is Toph gonna be polite and cooperative the moment they meet her because you should never be rude to people? Is Zuko just gonna be a good guy pretending to be evil because no one understands character growth and nuance is too subtle?

#from the desk of anachron#ugh#the tentative hope I had for the remake is shriveling#the character growth and development and becoming more well rounded people through world travel was my favorite part of the show!#they experienced things and met people and learned how other people live and think and they LEARNED FROM THAT!#that was the POINT

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

black eagles relationships i like but don’t see talked about enough

Ferdinand and Petra - I adore their supports. You see a lot of Ferdinand’s dorky side with his reading about historic weapons, and you see that he is genuinely curious about Petra’s culture. He admits that he initially didn’t realize how sophisticated Brigidian techniques are and I just adore his vulnerability with her. And then there’s Petra in their A support, admitting she found a second home in Fòdlan, and the two discuss their loneliness? It’s such interesting insight into both characters (especially Ferdie; I’d say these are some of his most well-rounded supports)

Hubert and Dorothea - Dorothea sees right through Hubert’s edgy theatre kid persona. She approaches him like she would any friend right from the beginning and teases him about his love life. She also respects and believes him when he says that unrequited love isn’t his motivation. I would’ve liked a conclusion that wasn’t Dorothea suggesting they marry, but it is really funny that she did that. I love their paired ending too--completely platonic espionage opera! What could be better?

Hubert and Byleth - in my head they have a quirky sitcom where Byleth keeps trying to arrange Edeleth/Ferdibert double dates and Hubert has to attend them. (but seriously, the appeal of Hubert is looking at this man and saying “I’m gonna make you like me”, and then you do it). Outside of my shipping biases, his threats to you are funny as shit considering that he has no power over you and he’s always dying in battle, but once you win his trust he admits that despite looking Blatantly Evil, he truly abhors TWSTID and is already planning their follow-up war. I could easily see him and Byleth co-leading the war in the shadows (and that’s where the dialogue of the aforementioned platonic Huleth workplace comedy takes place). Also my friend who played as m!Byleth told me the “we could be a couplet of birds” line in the A-support still exists regardless of gender. Hubert is demiromantic bi and you CANNOT change my mind

Edelgard and Petra - “Don’t settle for being the bird. Be the arrow instead” Both have a great deal of mutual respect for each other, even though Edelgard is heir to the nation that has kept Petra’s country down for years. You see the same beliefs Petra holds in her supports with Caspar here--that being, “we are not our parents, we can make different choices”. It’s a shame they only have 2 supports. I think it would’ve been cool to see Petra asking Edelgard for Brigidian independence or otherwise talking about how she can achieve her goal.

Edelgard and Linhardt - I actually think people talk about this a bit, but it’s one of my favourite Black Eagles support chains so I have to mention it. This one is the key to understanding that Edelgard’s better world is only possible in her route, when she has the support and opportunity to trust others enough to learn how to listen to them and consider their perspectives. I advise anyone who thinks Edelgard would be a brutal dictator to watch these supports, because they so blatantly contradict that idea? Linhardt initially frustrates her because she knows he’s talented and smart but he doesn’t want to do anything to help the world with that. Characters like Linhardt are usually given an arc in which they overcome an initial selfishness to help others. This is not that. These supports are about Edelgard learning to understand Linhardt and accommodate him. Edelgard agonizes over finding the perfect way to allow him to do his research in a way that suits him--and when she senses his hesitation at her initial plan, she presses him for the problem and reconfigures the idea because she won’t put him in a situation he’s not fully content in. This is astounding character growth (from both of them, but mostly Edelgard). Also the struggle depicted in this chain is just something that spoke to me when I first saw it--”be useful” versus “learn for knowledge’s sake” is pretty much my exact struggle in life 😂 Seeing two of my favourite characters reach a resolution that satisfied both of them was hopeful, to say the least.

Caspar and Ferdinand - What strikes me about their supports is that it compares and contrasts these characters’ ideas of justice against each other. Honestly, the Black Eagles as a whole have takes on morality that are just slightly skewed, and these characters’ arguments about it exemplify it. Caspar just thinks that people who hurt others should be hit right away, head empty no thoughts but j u s t i c e. Ferdinand initially believes that all sense of justice comes from being nobility, and with that comes an obligation to be morally superior. Having Caspar just go “uh yeah, what does nobility have to do with it? I just had to hit that guy” is one way in which Ferdinand’s ideals are challenged. It’s a cool contrast that I think highlights an interesting aspect of the Black Eagles and what they were taught.

Dorothea and Bernie - I love everything about their interaction. If Dorothea were a lesser character, she’d be the mean popular girl who shames Bernie for her messy hair and her anxiety. Instead, Dorothea is patient and Bernie is like “oh no she’s Too Cool for me”. Dorothea also makes note of what Bernie says as she gets too anxious to continue the interaction and aims to comfort her in their next support. We get a good Bernie character moment in their B-support, where she mentions her father ruining her friendship with a commoner boy--and a cathartic moment where Dorothea tells her that her father’s an asshole and that they’re going to be friends anyway. Bernie cries in Dorothea’s arms and AHHHH why didn’t we get MORE of this???

Bernie and Petra - If I could add any support and ending to the game, it would be Bernie/Petra. They have such a good starting point--because of Bernie’s anxiety and Petra being a second language speaker of Fòdlandish, they are prone to miscommunications (which is the general theme of early Bleagles supports). They had a nice 2-support arc where they understand each other a little better--but then there’s the paralogue, where Petra encourages Bernie to come to her homeland with her and Bernie realizes she wants to travel and see amazing things like carnivorous plants. This is fantastic character development for her and is a satisfying conclusion to her arc. I feel like most of Bernie’s endings involve her just reverting back to her hermit self instead of developing a balance between who she was at the beginning and who she’s grown into. I think Petra would offer to let her come to Brigid again, where she helps her navigate a new language and culture. Bernie’s anxiety is still bad but Petra has been in her position and can offer advise and reassurance. Petra is also patient and would give Bernie a safe little house near the carnivorous plants for her to retreat to when overwhelmed. It becomes both of their refuge, with Petra taking time away from her regal duties to spend time with Bernie and her art and her stories. Whether it’s romantic or platonic is up to preference but I low-key ship them 😏

#black eagles#ferdinand von aegir#petra macneary#hubert von vestra#dorothea arnault#caspar von bergliez#bernadetta von varley#edelgard von hresvelg#linhardt von hevrig#byleth eisner#fe3h

178 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who are you two favourite cats in each clan you're in? And why?

ohhh man i answered an ask similar to this a little while ago but slimming it down to just two per clan is hard...most of my answers have remained the same but there are some alterations from last time!

NETTLECLAN

berryclaw

everyone knows how much i adore berryclaw. she’s been an absolute favorite character of mine for years now, and the more time that passes, the more fond of her i am. she’s so hardworking, striving to build the best life she can have, and i always want her to succeed. she has a level head and good judgement but still obviously struggles when it comes to feeling in control / like she’s making the right choices and that makes her particularly relatable, i feel.

rabbitpaw

rabbitpaw’s a new addition since the last round, and she’s been stealing my heart from her earliest days. she’s just so completely sweet that i can’t help but adore her. the generosity and understanding she extends to everyone she knows is so charming and also a brilliant contrast with her much more self centered sisters, and okay, sue me, i’m biased because of just how precious her dynamic with flintheart is. her love for her uncle and her total faith in a cat who really has a hard time believing in himself is just so heartwarming and really does highlight just how big of a heart rabbitpaw has.

CREEKCLAN

currentstar

i will be a currentstar stan until i die. he’s so well written as a breath of fresh air against a backdrop of cats who tend toward the more chaotic side of things. currentstar’s not devoid of his problems, but i adore how unique he is in his viewpoints and behaviors. it’s easy enough to be a rebel, but currentstar is incredibly special because of how devoted and dedicated he is. snow did an amazing job of picking him up after a streak of dropped adopters and has made him so interesting and so sympathetic. he has to be this upstanding figure for everyone else’s sake and does so much to support his clan that everyone kind of just seems to take him for granted...more people need to appreciate my lovely lovely boy.

applepaw

i was drawn to applepaw almost instantly, and for good reason! she’s such a complex character due to being placed in the role of a “hero” or figurehead for the whole eden cause. the contrast between her and her brothers is incredible because she is, in theory, a much more realized and... secure sort of cat, except just kidding, this girl is full of insecurities. i love the fact that she manages to maintain an air of being more closed off and reserved without showing outright hostility, and i’m always eager to read roleplays that she’s involved in.

JAGGEDCLAN

stonefang

what is there to say about stonefang that i haven’t already? she’s had such a brilliant arc of development, going through trials and all sorts of suffering to become the cat she is, and it’s all been written so stunningly. stonefang is absolutely the hero of the story that you adore, root for, and desperately want to see crawl her way out of the hell she’s been put through. her sharp wit and judgement paired with her selfless acts to protect her loved ones makes her so enjoyable, and i also adore getting to see her slip away from being the more warm and kindhearted sort of cat she usually is when her security / loved ones are threatened. stonefang going crazy on fogclan always brightens my day, you get ‘em, girl.

eveningstorm

miss sunshine herself, despite her name. eveningstorm’s a cat i had to come around to really adoring after just liking her casually for a while, and i am so glad i saw the light. she’s got a tender heart and a level of sensitivity that makes her capable of helping others without ever giving in herself. she’s not weakened by her kindness but is instead fueled by it, and that makes her stand out against more typical shy and soft personalities that you might see elsewhere. her relationships are compelling and interesting, especially when it comes to her tendency to just...break down the barriers of cats who have spent so long building them up. she’s really just a little fluffy treasure and i adore her wholeheartedly.

FOGCLAN

lilystar

lilystar is easily one of the most complex, morally gray characters in the group. so many of her decisions and her choices have been flawed, but that’s what makes her feel real and drives me to love her. i feel like more often than not people are wary of having their characters make mistakes or take a path less traveled by, but lilystar always seems to go where no one else will. she’s driven, fiery, and certainly not the easiest cat to get to know, but her actions all click into place and make logical sense considering what she’s been through. her storyline is undeniably tragic, and the echoes of palestar’s influence that still run through her life give her such an intriguing thought process.

bramblefang

who doesn’t have a soft spot for bramblefang? he’s a special brand of gruff but not outwardly hostile that i feel is difficult to keep a balance of, but it just works so well for him. he has super clear motivations and the way he’s now developing ties in fogclan that allow him to let go of past hurt with his sister and the manipulation palestar put him through is so sweet. he definitely hasn’t flipped completely over to being soft, but i like seeing touches of it in him now. he knows when he needs to have a hard head and when it’s better to step back and be understanding, which is such a good development for him considering the way he used to view the world in a more black and white sense.

TRIBE OF TWISTED TUNNELS

spark feather

sometimes you just have to cheer for a character whose life seems to go wrong at every possible turn. spark feather has never had it easy, and as time goes on, he’s started to play a more active role in screwing himself over, which is a super interesting thing to see develop. he went from basically being a victim of circumstances that built him up to a cat who was capable of making all the foolish, rash mistakes he’s made now. everything about his arc feels natural and he’s still incredibly easy to sympathize with even when he’s doing the opposite of what he should be. he doesn’t get to show it often anymore, but i love his tender side that is displayed to his kits. he’s gone through so much growth already, and i’m eager to see where else he ends up now that his life is sort of starting to get stable again.

butterfly

sort of similar to spark feather, butterfly started a victim of circumstance...and she’s stayed that way all along. her life is absolutely devastating to watch because it never seems to want to treat her right despite her best efforts to be so good, so honest, so true to herself. i’m obsessed with her fixation on truth telling, and it’s such a brilliant trait for her to develop considering that basically no one in her life has ever been entirely honest with her. she’s been forced to navigate so many complex feelings from the moment she was born, and i have so much love in my heart for this poor little darling...it’s insane to think she’s really growing up and getting older now, but seeing her mature and come into herself is comforting after all the struggles she’s been forced through.

#berryclaw#rabbitpaw#currentstar#applepaw#stonefang#eveningstorm#lilystar#bramblefang#spark feather#butterfly#nettleclan#creekclan#jaggedclan#fogclan#tott#anonymous#ask

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

kizuna countdown part 2! yup i just did them all in one go, everyone who’s doing it day by day, have fun! See y’all on Friday!

Favorite Chosen Child-Digimon bond

... uh... so I guess I already answered this in the last question XD I think it's because it's so difficult to think about the Digimon without thinking a lot about the relationship they have with their partners. So I'll just let this one lie, I guess.

Favorite Chosen Children friendship

I pretty much like any relationship dynamic that involves Taichi.

Taichi & Yamato show the most growth, both in themselves and in their appreciation and respect for each other. Taich comes at Yamato expecting to make friends just by being himself as always. Yamato's built up walls to keep himself from getting hurt, plus there's a side to him that wants to be as free Taichi, and he winds up feeling jealous. Then there are ways in which they are legit different which adds even more friction. Their friendship comes out on top because both of them are extremely loyal to their friends at their core. They rock. I loved them in Tri too, when Taichi was acharacteristically waffling around and Yamato was even more concerned about it than the confused viewers hahahaha.

Taichi & Koushirou because they're the opposite of him and Yamato, their friendship is steady and strong throughout. They already respect each other from day one. Taichi puts a lot of faith and trust in Koushirou's abilities and relies on him to get him out of a pickle, even one he's made on his own. Koushirou is a bit shy and not exactly afraid to speak up, but not 100% convinced that his contribution is valued. Taichi helps him see his own worth. And Koushirou believes in Taichi :')

I also love him and Sora and Hikari. For friendships that don't include Taichi, my favs are:

Takeru & Hikari because they're really POWERFUL when they're together (teasing Daisuke for example)

Sora & Koushirou Managing Things, Somehow

Koushirou & Mimi driving each other crazy while really valuing each other

Daisuke & Miyako ^ similar dynamic

Ken & Miyako, I know it becomes a romance, but I loved it when they were kids and it was like Ken and Hikari were off being angsty together and Miyako's like I FEEL LEFT OUT and whines about and then kicks their butts to make the sun shine

Favorite Adventure series villain

Etemon! just kidding. Though the Etemon arc was so great for Taichi that I really enjoy it XD

I'd definitely pick the Dark Masters. Devimon was your typical RPG villain, then Etemon was nonsense run amok. Myotismon was the most fun storyline, what with going back to the human world and the search for the eighth child... I especially loved the chaos when the kids are all separated throughout the city.

But yeah, it'd be the Dark Masters, mostly because I loved how much the kids' resolve got tested when they had to decide for themselves to go to the digital world instead of just being thrown in there. The only one who's had to do that before was Taichi. They fought and they lost a lot of friends, and their team splintered and we saw new sides to everyone. It was harsh. About the villains themselves, MetalSeadramon was whatever, but Puppetmon with his envy and vulnerability and weird relationship with Cherrymon was so interesting to me. Machinedramon was downright terrifying. And then Piedmon playing everyone like marionettes and taking down the trump card as soon as it appeared on the scene... it all led to my favorite moment when the kids are running away one by one and sacrifice themselves to save each other. Sora's moment saving Takeru and Hikari while grabbing Yamato's doll was absolutely epic.

Favorite non-partnered Digimon

Piximon! I loved and wanted more of his training sessions. Wish he'd been like Rafiki and just followed Taichi around smacking him on the head with his stick.

Does Gennai count? He's not a Digimon so I guess not, but I loved Gennai too. He was useful. And also useless. I mostly liked it when he was useless xD

Also Whamon. Traveling in the belly of a whale is awesome. And I was so upset when he got killed.

Also Leomon & Ogremon should count as one of my favorite friendships.

Favorite ship / OTP

So, my number one Digimon OTP is Joumi. Always has been. I like it for a lot of similar reasons that people like Koumi, I guess. But the reason I glued onto Joumi mainly happened in Dark Masters when they were traveling just the two of them for a while. Mimi is positive and outspoken and caring despite being a bit self-absorbed. Jou is reliable, steady, and protective, even though he's also perpetually stressed out. They can both be panicky, but they grow out of it a lot. I think they're pretty realistc in personality and that's one reason I like them together: no one's unusually adept at something or other, they're just kids. They confide in each other about their struggles and they pick each other up. (I loved Ketsui for those moments! Such gifts)

Other ships I really enjoy are Taishiro, Taito, Miyakari, Daiken, Takari, and Daikeru. I also love one-sided Taidai and Mimiyako!

A friendship you'd like to see developed

Honestly? Sora and Miyako. The 02 kids inherited the Adventure team's crests, and each seemed to have a slightly stronger bond with one predecessor than the other. Daisuke had interesting dynamics with both Taichi and Yamato, so that was okay. Iori seemed to have more significant moments with Jou than Koushirou, I think because the sort of knowledge that Iori quests for is a different kind. Miyako is really, really similar to Mimi, her passions are just more hard sciences than artsy-fartsy. But Miyako really never gets any moments with Sora at all? There's that one when she's panicking about being a Chosen in like episode 2, and I can't think of any after that. I would love to see Sora big sister-ing Mimi, helpig her bring out her sensible side, since Mimi's got the eccentric covered.

I'd ALSO like to see Hikari & Sora have a great friendship. One that isn't entirely based on worrying about Taichi x'D

Favorite Kizuna character profile

Takeru's because I just love that he's in a children's lit club!

Favorite Kizuna promotional art

I... haven't been paying attention, so this isn't a real answer, but that one with the boys eating ramen I guess. I even wrote a ficlet for it lol.

Favorite Tri. installment

Kokuhaku!!!! That destroyed any reservations I still had about Tri. It was epic. Somewhat undercut by the fact that we all knew the Digimon would wind up getting their memories back eventually, but I was okay with just enjoying the ride until we got to that point. It was great. I loved the sacrifice the Digimon were willing to make, I loved the secret farewells each partner took, I loved Takeru's protectiveness, Koushirou's breakdown, and Tentomon's strength. Like seriously, he gets all the MVP awards.

Favorite non-Tri. Adventure movie

Our War Game. It's just classic. Plus, Bolero.

Favorite character besides the 12 kids & their partners

Oh, I guess now I could pick Gennai if I want. But I think I'd pick Meiko. I was so not feeling her when Tri came out because I expected her to be the Typical Anime Movie Newbie, who's almost always a girl, bland and uninteresting, eating up valuable screen time from the characters we actually want to see, magically saves everyone and then never appears again.

Meiko did not end up being that girl. Her shyness and awkwardness might have been annoying if they hadn't been tempered by her personal journey through the six movies, and I ended up really liking having a shy girl on the cast. It was refreshing and it was beautifully cast against Mimi. Mimi/Meiko FTW. And she hd real female relationships - with both Sora and Mimi. Her protectiveness of Meicoomon, but also her selfishness, and the terrible decisions she had to make, the way she struggled with self-pity and real honest grief... it ended up really moving me. I think she became very well-rounded and added a lot to Tri.

If Tri had been just one movie, like those anime movies I was expecting, I think she would have been That Girl, but fortunately with six we had plenty of time to get to know her.

(Bonus) Freebie! Talk about something we didn't cover :)

Well, we did lots of favs, so how about a "least fav"?

Of course I don't have a least favorite Chosen, or Digimon. In fact the only thing I'd really pin as a big disappointment happened in Tri. I love Tri but it's certainly got its holes, and for me, Himekawa Maki is a big one. I hate that we just left her wandering in the dark ocean. I hate that were wasn't more expansion on the original Chosen team. I remember when I was a kid and we found out in the last ep or so of Adventure that there had been kids before Taichi and co, I was annoyed, I'd wanted them to be the first.

But I was also curious. With Tri, we finally found out some about that... but only scraps. Who were the others on the team? Where are they now? What's their relationship with Digimon, and if they don't have one anymore, why? What would they say about Daigo's death and Maki's disappearance? Honestly I didn't want to dedicate more time to them at that point (even with six movies they couldn't cram everything in - much as I love Ketsui, I think it should have been a bit different, and moved the plot along faster). But I also hate that we finally learned some stuff about them and in the end were just left with even more questions.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

MARTHA JONES Is The Perfect DOCTOR WHO Supporting Character

Having recently rewatched Series 3 of Doctor Who, not only is it my favourite of new Who, but so is Martha Jones. I’d also go as far as saying she is the perfect supporting character.

First off, Freema Agyeman was the perfect casting decision. The showrunners were really impressed with her in the minor role she played at the end of Series 2. Instead of ignoring this fact, the writing brings up how it was Martha’s cousin who died at the Battle of Canary Warf. This accomplishes a couple of things; it explains how the same actress played two characters on the show without causing continuity errors. Then you have the Doctor forced to be reminded of said battle.

And Rose.

Which brings up to how the Doctor is still dealing with losing Rose at the end of Series 2. He needs a new companion and when a smart, clever, resourceful doctor presents herself to fill the spot, they both take it. The show gives us two doctors for the titular Doctor to choose from to accompany him. It’s obvious why he’d go for Martha given how scared the other candidate is. Unlike Rose, Martha was whisked into an adventure along with a hundred other people yet she’s the one who joins him in the TARDIS.

Rose’s shadow looms long over the Doctor. The Time Lord takes Martha to the same places he took Rose. People have criticized the showrunner Russell T. Davies of being obsessed with the character of Rose and the drama that came with it, but for me it just comes off as staying true to the character of the Doctor. He isn’t just going to forget about Rose and how in sync they were. That would be very disrespectful to Rose and her fans. Sadly this means Martha does get left behind as a character. She fulfills her purpose perfectly even though it means she cannot compete when it comes to Rose. It makes her character tragic and very sympathetic.

Snog her, you idiot!

Maybe it’s just me finding Freema and Martha attractive but as an audience member you really wish the Doctor could see Martha the way she sees him. Albeit, the Doctor shouldn’t really be dating any of his companions to be honest. Still, Martha isn’t getting enough out of their relationship or lack thereof which is sad.

Speaking of sad, Martha can show her vulnerability as easily as she can be sassy and funny. She can stare at the Doctor with puppy dog eyes in one scene yet demand answers about him and his past the next. All these emotions come off naturally, both in the writing and with Freema’s acting. She’s just a perfect blend of a supporting character. Balanced like all things should be.

Now, having said that, there is a problem with Martha. Despite being a balanced character that also means she doesn’t have the highest of highs or the lowest of low points. For the most part, Martha lacks major strengths and weaknesses that would solidify her as a great character.

Martha’s fun even when she tries too hard to be funny.

For that to happen, Series 3 would have needed a Martha-centric episode. If she had wanted to go back to being a doctor for a while then maybe her personality would have shone through more. This would cause a detour in the story and mess with the pacing though. One could argue that “Blink” does that, but who’d want to get rid of that episode? Plus the Doctor-lite episode was needed so both Tennant and Agyeman could do more shooting for other episodes.

I have loads of ideas for a Martha-centric episode...

Martha is a perfect supporting character, as in she services both the protagonist, story and plot. Supporting characters just tend to not be fleshed out well enough to be great characters. Arguably this changes when Martha decides to leave the Doctor. I haven’t seen her adventures in Torchwood but (I will check them out now!) Martha’s return in Series 4 was glorious. When we last see her in Ten’s last episode she’s an outright badass. So there is growth and character development, I just wonder how much of that is offscreen.

Martha’s main weakness, if you can call humanity that, is her feelings of inadequacy brought on by her unrequited crush/love for the Doctor. It humanizes Martha, adding to the juxtaposition between her and the inhuman Time Lord. Again, serving the protagonist and the story perfectly. The one-sided love story just never goes anywhere. Martha’s decision to just get out is sensible and it makes her extremely likeable and wise. It provides a character arc for her, but it’s not exactly memorable nor does it propel the story into new heights.

Martha literally gives her last breath to the Doctor as they are about to suffocate on the Moon.

That said, Martha went way beyond the call of duty, sacrificing herself to help the Doctor. Especially during the two-parter "Human Nature/Family of Blood” where Martha had to witness the Doctor falling in love with another woman while trying to keep the Time Lord safe from evil aliens. All the while having to put up with the prejudiced attitudes of the early 20th century England.

Right before Martha schools her on all the bones in her hand that’s about to pimp slap her.

In the same two-parter, when the amnesiac Doctor-turned-human falls down the stairs, Martha comes over as soon as she hears of it. Concern for the Doctor’s wellbeing is the first thing on her mind. Sure, Martha’s trapped there with the Doctor being her only way out, but it never comes across like that. The things Martha endures are sacrifices she’s deemed necessary. It really speaks volumes about the true grit of her character.

Waifu material.

She never becomes bitter or hardened by any of it either. Yet she isn’t without some sass either. When Martha’s told she should knock before entering, she steps back towards the door, knocks it and comes back. Martha Jones is such a well rounded character it’s a shame we only had her for a single season.

I’ll reiterate; all this this makes Martha my favourite New Who companion. It makes her the perfect supporting character.

I was going to make a joke about this, but I think the logo speaks for itself...

Martha’s own supporting cast reflects this as well. They all serve to paint a picture of Martha and pushing the story forward. Martha’s mother Francine is excelently utilized with very little screen time. Her skepticism towards the strange Doctor is only natural. It makes perfect sense for Francine to work with Saxon’s people who seemingly want to protect Martha like she does. This side plot in “42″ is actually the best part about the otherwise mundane enviromentalist episode.

Martha isn’t a jokester, but she has her moments. Kudos to Freema’s versatility as an actress.

As a character though, Jackie Tyler, annoying as she could be at times, is far better though. Jackie’s flirty personality, her accent and overall attitude towards life just shines through her every delivery of a line of dialogue. There are plot involving Jackie’s dead husband coming back to life and creating a deadly time paradox, too. Whereas Martha’s dad dating another woman doesn’t have effect on the plot. It doesn’t even phase Martha herself, she just tries to steer clear and juggle between her mom and dad which is easy because by now she lives on her own. Drama free.

That is when she isn’t being jettisoned into the sun!

Side note, I’m glad the character got a happy ending, albeit not with the Doctor like she wished. After all the hardships she endured and sacrifices she made for the Doctor for very little reward, she’s earned a little peace and quiet. She wasn’t lost on a parallel Earth nor forgot her adventures. She didn’t “die” like Amy, Rory and Clara.

It would have been absolutely terrible had Martha died. She’s my favourite of the bunch so it’s good to know she’s still out there somewhere in the Whoverse. The fact she could be easily written back into the show some day warms my heart.

For future reference, should Martha come back to the show and should the writers decide to kill off her character... like they are doing with the show proper at the moment... then allow me to give the showrunners and writers some advice. If Martha has to die, make her sacrifice herself for the Doctor one last time. As a one final act of love towards the man (assuming he’s back to being a man).

She’s talking about Shakespeare, but Martha’s line is very indicative of her relationship with the Doctor.

Don’t give us Mad Martha who decides to burn down whole cities full of people, okay. Don’t give us that “Martha kinda forgot her Hippocratic Oath” crap. You got that? Just making sure...

Anyway, Series 3 wasn’t the end for Martha and I’m so glad the character came back in Series 4 and like I said, I’ll be checking out Torchwood for more Martha appearances. But we’re here to talk about her as a companion so let’s get back on track.

That’s what she said about my tangent.

Now, you could get a good episode about Martha’s family drama, much like how Rose changed time to save his dad. But it’s not really necessary. The family drama in Series 11 has certainly shown how dull and dreary stories like that can be. That is why, even though Martha and her family aren’t exactly great characters that provide great stories, they are perfect at providing a clear context to the imaginary world that the Doctor, the TARDIS and time travel represents.

Freema sells that magical moment of a companion stepping into the TARDIS for the first time perfectly.

Again, perfect supporting characters that don’t waste time away from the things people actually watch the show for. That said, I wouldn’t have minded seeing a cat fight between Francine and her ex husband’s new bimbo girlfriend!

Just a single scene like that would have been endlessly entertaining and damn memorable!

Imagine that but between her and the bimbo: “Keep away from my husband.”

Martha’s sister Tish fares a lot better as a character as far as personality goes. There isn’t really a sibling rivalry going on, but Tish’s remarks about Martha dating a science geek speaks a lot about both her and Martha’s characters. What they look for in a man. When the Doctor asks what a science geek means, Martha explains it’s just someone who’s passionate about science which makes the Doctor happy. Which is what Martha wants, whether she was telling him the truth or sparing his feelings with such an interpretation. Brilliant writing for the characters all around.

Tish working with both Lazarus and Saxon, even if both instances were brought about by Saxon himself, tells about Tish being drawn towards wealth and power.

She was even ready to “snog” a de-aged Lazarus!

Damn right, she is! Not just a pretty face but smart too!

I wish we’d have seen more of Tish. Her interaction with Martha really created a contrast that benefitted both characters. In “The Lazarus Experiment” especially, Martha gets to shine. After helping her family escape, she goes back for the Doctor against her mother’s wishes. Later, Tish comes along. Martha takes control and takes Tish with her so that the Doctor has time to defeat Lazarus himself. Martha let’s the Doctor shine and in doing so shines herself. Tish acts as a great supporting character herself by asking who the Time Lord is. At this point Martha already knows because she’s asked him herself, demanding answers.

“We need to talk.” Never a good sign except in fiction.

Martha or the handling of her character is often criticized for how she had a thing for the Doctor. Her character was much more. In an early episode “Gridlock” we get one of Martha’s best moments; when she demands answers about the Doctor. She forces the Time Lord to come out of his shell, to stop pretending everything was all right. The Doctor tells Martha about being the last of the Time Lords which fits perfectly to the story of the Series.

Namely that the Doctor is not the last of his kind.

The Doctor also mentions how the Time Lords were all lost in a Time War, battling against the Daleks. It’s a great segway into the next two-parter story about Daleks themselves. The story flows really well with one thing leading to the next. The pacing is really good while the characters remain true to themselves. That said, it’s good to have Martha around to challenge the Doctor.

Asking seemingly harmless questions like this is vital for good supporting characters. We get to see the Doctor’s reaction to his home planet being brought up.

That said, I should mention a couple of things. In the episode “Smith & Jones” the Doctor kisses Martha to mark her with some of his DNA. This is done on the fly and while the Doctor had a plan, I dislike how this puts Martha in danger. Now, she doesn’t get into any serious trouble but considering how trigger happy the Judoon platoon upon the moon are, things could have gone real bad. This kiss does start Martha’s infatuation with the Doctor so there’s that.

Wait, don’t snog her, you idiot! Now she’s in danger!

The Doctor’s indifference to cool and hot Martha does make him in return look cooler. Martha is essentially the Doctor’s cheerleader which, despite sounding as not complimentary, really is that. You need the audience to root for the main character and this is partly achieved through supporting characters singing their praises. Of course, the characters still have to earn that praise. You can’t just have characters emotionally validate themselves or others to the audience.

Though it doesn’t hurt when Shakespeare himself is singing your praises.

The downside to the Doctor’s indifference is that he does come across as a jerk at times. Now this can be either a good or a bad thing based on the audience. While Martha is perfect as a supporting character, you don’t want neither her or the protagonist to be perfect. The Doctor missing Rose, as annoying as that can be to some, is keeping true to the character. The Doctor is in mourning. It’s his grief period and Martha is there to help him through it. In doing so, Martha learns that she doesn’t want to wait forever for another person to notice her.

In one of the best episodes in New Who’s history, “Utopia” draws a parallel between Doctor and Martha and the Professor and his assistant Chantho. Much like Martha, Chantho is smart, kind and caring. Based on her interactions and demeanor, Chantho adores the Professor and like Martha with the Doctor, she has a crush on him. Both the Professor and the Doctor don’t notice these signs. For an individual episode this is all well and good, but given the secret about Professor Yana, this parallel is much more impactful than it seems at first.

Spoilers to a Series over ten years old; Yana is actually the Master. This twist alone, the callback to the concept of a fob watch allowing a Time Lord to masquerade as a human was a brilliant touch. Martha of course recognizes Yana’s fob watch instantly and again, Freema sells the feeling of terror and dread so damn well.

Later in the episode Martha recognizes the Master’s voice as Harold Saxon. The name we’ve heard all throughout the Series. A lesser show would not have given Martha’s character such insight. It’s one of the numerous details that make her character clever and likeable.

Unfortunately, likeable characters aren’t always the most compelling ones. This makes Martha an underappreciated companion in the series history. While Martha is my favourite, I can’t really blame the detractors. Martha Jones served her purpose on the show which meant couldn’t shine as brightly of a star of her caliber. I’d still take her any day over Clara Oswald who was such a bad supporting character that it encroached on becoming the Clara Who show. And I say this as someone who loved the past and future Claras and Jenna Coleman playing the character(s).

Anyway, back to the actual episodes. While context is key, I find it interesting how the Master kills Chantho, showing no regard for her life. Now, the Doctor does care about life and he’s risked his own life for Martha many times. Still, being around the Doctor, much like with the Master, is dangerous. Neither can truly love their companions the way they want. That parallel is fascinating and I’m glad Martha was allowed to walk away from it of her own free will. Definitely one of the reasons this Series has the best writing out of New Who.

One of the few times the Doctor rewards Martha’s loyalty and bravery. Her reaction to receiving a key to the TARDIS is everything!

Speaking of writing. Before Martha says her goodbye, she has to walk the Earth and spread the gospel of the Doctor to the people of the world. Many have criticized how the show made the Doctor out to be a god who regains his power through prayer essentially. Rightfully so because even in context the twist does feel outlandish albeit totally awesome. Subjectively I’d say it’s one of the best moments in New Who.

Basically, the people have been subliminaly made to vote Master/Saxon into office. Now the Doctor has tapped himself into the same telepathic field and receives prayers, the word “Doctor” across the world. This turns him basically invincible for a time. Time enough to defeat the Master.

Because the telepathic field had been established in a prior episode and its effects had been reincorporated over and over again in the form of a drumming that the Master himself heard inside his head, I find that the twist is properly set up. That and because Martha has spent a whole year travelling around the world acting as a cheerleader for the Doctor.

The best cheerleader you could ever hope for!

Though how the Doctor’s orders relayed by Martha never reached the Master’s ears is a mystery. Martha was aware of a traitor though and she spoke to her accordingly, feeding false information. I doubt she told the people about the telepathic field. The Master could not put two and two together when the Doctor himself told of the plan. To the Master it was just hope and prayer.

Suffice to say I have mixed feelings about the final twist. None of this detracts from Martha Jones as a companion though and that’s why I wrote this blog post about her. If you’ve managed to get this far I thank you.

Boy, that was a lot of out of order, wibbly wobbly rambling about a show that I love and a companion I adore. Started well, that blog post.

<3

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

WIP Prep (tag)

I was tagged by @paladin-andric -- thank you!!! I loved filling this out, and sorry for the delay!

Rules: Answer the questions, then tag as many people as there are questions (or as many as you can).

The Colors of War

FIRST LOOK

1. Describe your novel in 1-2 sentences (elevator pitch)

Sent from London, England to Maine, USA by her guardian to escape The Blitz of World War II, Marjorie Borchert is left to navigate her young adult years in a tight-knit and foreign town. As the years progress, she learns war stretches far beyond the front lines.

2. How long do you plan for your novel to be? (Is it a novella, single book, book series, etc.)

A single book with possibly a collection of shorts from the other character’s lives.

3. What is your novel’s aesthetic?

Chilly mountains and moose.

4. What other stories inspire your novel?

Little bits from Number The Stars by Lois Lowry and the character of Emily Bennet from the Molly American Girl series.

5. Share 3+ images that give a feel for your novel

MAIN CHARACTER

6. Who is your protagonist?

Marjorie Borchert. She is in her mid-teens at the beginning of the story. Moody to say the least, but she has a big heart.

7. Who is their closest ally?

Daniel Reynard. Nikita Savas is a close second but Marjorie’s had a special bond with Daniel from the beginning.

8. Who is their enemy?

Kate, Beatrice, and Gina. Kate is the worst despite the fact Marjorie shares a room with Beatrice.

9. What do they want more than anything?

For things to be as they were before the war.

10. Why can’t they have it?

Her parents were both killed.

11. What do they wrongly believe about themselves?

She believes nobody wants her -- which is understandable after being passed off to strangers by her guardian and, in a way, her brother.

12. Draw your protagonist! (Or share a description)

I’m not much of an artist and she’d look like a cartoon, do description it is.

Tall, though not towering over everyone. She keeps her brown hair short or shoulder length until she’s older. She’s thin, possibly malnourished, when she first comes to America. She fills out a bit the longer she’s at the farm and eating three full meals a day. She’s pale, partly due to locations she’s lived. She had prominent German features, most notable, her accent which is mixed with a British tongue.

PLOT POINTS

13. What is the internal conflict?

There’s different stages I’ll say. In the beginning, it’s about Marjorie trying to find her place in this small and established community. Her biggest conflict being a target for the prejudiced Kate. Then it moves on to the progression of the war and her fears around America’s involvement. But she comes to see that war doesn’t just affect those fighting or being captured and bombed. She also sees how different people handle things differently. Priorities fall into place through this.

14. What is the external conflict?

Trying to get by and adapting to the changes the war is bringing to the community. Acceptance, too. Internal and external kind of work together.

15. What is the worst thing that could happen to your protagonist?

Losing her brother for good and/or not being able to return to England.

16. What secret will be revealed that changes the course of the story?

My only secret might not end up working. There would have to be a second book. Either way, I’m not going to reveal it. It might end up being one of things only me and a couple of my writing friends will ever know....

17. Do you know how it ends?

Yes, unless Marjorie decides to change her course of action.

BITS AND BOBS

18. What is the theme?

Acceptance and making the best of a bad situation.

19. What is a recurring symbol?

Change.

20. Where is the story set? (Share a description!)

Jackman, Maine, USA. A small town with a population under 1,000 a few miles from the border of Canada. It’s a heavily wooded area with beautiful mountain and lake views. Lots of wildlife, too. The town is small, running along a single street branching out into houses.

21. Do you have any images or scenes in your mind already?

So. Many.

22. What excited you about this story?

The time period. I’m a history buff and the 1940s has always been my favorite era.

23. Tell us about your usual writing method!

Procrastination. That’s really it. I do my best writing at five in the morning and knowing I have to pick my little cousin up from the bus in a few hours.

I tag (if you’d like): @throughwordsiescape @silverscreenwriter and @rachelradner

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I started the month in a really bad reading slump, so my main goal for the month was to get over that. Thankfully I successfully revived my love and enthusiasm for reading, and managed to have a really successful reading month. I’ve never read so many books in a month before in my entire life, and I’m feeling really good about it. I picked up what I felt like, and that meant I read a lot of graphic novels.

The House with Chicken Legs – by Sophie Anderson

All 12-year-old Marinka wants is a friend. A real friend. Not like her house with chicken legs. Sure, the house can play games like tag and hide-and-seek, but Marinka longs for a human companion. Someone she can talk to and share secrets with.

But that’s tough when your grandmother is a Yaga, a guardian who guides the dead into the afterlife. It’s even harder when you live in a house that wanders all over the world . . . carrying you with it. Even worse, Marinka is being trained to be a Yaga. That means no school, no parties–and no playmates that stick around for more than a day.

So when Marinka stumbles across the chance to make a real friend, she breaks all the rules . . . with devastating consequences. Her beloved grandmother mysteriously disappears, and it’s up to Marinka to find her–even if it means making a dangerous journey to the afterlife.

With a mix of whimsy, humor, and adventure, this debut novel will wrap itself around your heart and never let go.

This was such a quick, enjoyable read, and an interesting twist on the Baba Yaga story. It’s such a whimsical story, I loved all the interesting details that were woven throughout the book. I was quickly absorbed by Marinka’s life, and invested in her story. There are some really interesting themes explored throughout, and Marinka’s reactions always felt really genuine. I loved watching her character develop and grow throughout the story as she came to terms with her situation, and explored her identity. I can see why this book was released to so much praise, I’m just so glad I picked it up.

Rating: 4.5 Stars

Their Fractured Light – by Amie Kaufman & Megan Spooner

A year ago, Flynn Cormac and Jubilee Chase made the now-infamous Avon Broadcast, calling on the galaxy to witness LaRoux Industries’ corruption. A year before that, Tarver Merendsen and Lilac LaRoux were the only survivors of the Icarus shipwreck, forced to live a double life after their rescue.

Now, at the center of the galaxy on Corinth, all four are about to collide with two new players in the fight against LRI. Gideon Marchant is an underworld hacker known as the Knave of Hearts, ready to climb and abseil his way past the best security measures on the planet to expose LRI’s atrocities. Sofia Quinn, charming con artist, can work her way into any stronghold without missing a beat. When a foiled attempt to infiltrate LRI Headquarters forces them into a fragile alliance, it’s impossible to know who’s playing whom–and whether they can ever learn to trust each other. With their lives, loves, and loyalties at stake, only by joining forces with the Icarus survivors and Avon’s protectors do they stand a chance of taking down the most powerful corporation in the galaxy—before LRI’s secrets destroy them all. The New York Times best-selling Starbound trilogy comes to a close with this dazzling final installment about the power of courage and hope in humanity’s darkest hour.

This book took me so long to read, it just seemed to go on forever. I know that this is mostly because of my reading slump which hit right as I was reading this book, but I also feel like a lot of this book was about moving the characters towards a meeting point where they could then go on and finish the story. It almost feels like it could have been two books in that sense. One following Sophia and Gideon, and then a final book following all the characters once they meet.

Rating: 3.5 Stars

Before She Ignites – by Jodi Meadows

Before

Mira Minkoba is the Hopebearer. Since the day she was born, she’s been told she’s special. Important. Perfect. She’s known across the Fallen Isles not just for her beauty, but for the Mira Treaty named after her, a peace agreement which united the seven islands against their enemies on the mainland.

But Mira has never felt as perfect as everyone says. She counts compulsively. She struggles with crippling anxiety. And she’s far too interested in dragons for a girl of her station.

After

Then Mira discovers an explosive secret that challenges everything she and the Treaty stand for. Betrayed by the very people she spent her life serving, Mira is sentenced to the Pit–the deadliest prison in the Fallen Isles. There, a cruel guard would do anything to discover the secret she would die to protect.

No longer beholden to those who betrayed her, Mira must learn to survive on her own and unearth the dark truths about the Fallen Isles–and herself–before her very world begins to collapse.

Why aren’t more people talking about this book? It’s just so good, I loved every minute of it. I’m actually kind of mad that I don’t have the second book ready to start right away, but I will be pre-ordering that very soon. There is so much that I like about this book, firstly, this book has actual dragons in it!

Rating: 5 Stars

Bruja Born – by Zoraida Cordova

Three sisters. One spell. Countless dead.

Lula Mortiz feels like an outsider. Her sister’s newfound Encantrix powers have wounded her in ways that Lula’s bruja healing powers can’t fix, and she longs for the comfort her family once brought her. Thank the Deos for Maks, her sweet, steady boyfriend who sees the beauty within her and brings light to her life.

Then a bus crash turns Lula’s world upside down. Her classmates are all dead, including Maks. But Lula was born to heal, to fix. She can bring Maks back, even if it means seeking help from her sisters and defying Death herself. But magic that defies the laws of the deos is dangerous. Unpredictable. And when the dust settles, Maks isn’t the only one who’s been brought back…

This was everything I hoped it would be. I really enjoyed seeing more of the world in this book. I really love the magic system and the world building. I was worried about whether I would enjoy Lula’s perspective as much as I did Alex’s, but I needn’t have worried. This book was fantastic, and I already can’t wait for the next one.

Rating: 4.5 Stars

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them – by

A brand new edition of this essential companion to the Harry Potter stories, with a new foreword from J.K. Rowling (writing as Newt Scamander), and 6 new beasts!

A set textbook at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry since publication, Newt Scamander’s masterpiece has entertained wizarding families through the generations. Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them is an indispensable introduction to the magical beasts of the wizarding world. Scamander’s years of travel and research have created a tome of unparalleled importance. Some of the beasts will be familiar to readers of the Harry Potter books – the Hippogriff, the Basilisk, the Hungarian Horntail…Others will surprise even the most ardent amateur Magizoologist. Dip in to discover the curious habits of magical beasts across five continents…

I borrowed the audiobook from my local library, and I really enjoyed it. I wasn’t sure if this book could work well as an audiobook, but it really does. It’s narrated excellently by Eddie Redmayne, who is in character as Newt Scamander for the entire book. The whole thing is just really well done.

Rating: 4 Stars

Giant Days: volume 4

It’s springtime at Sheffield University — the flowers are blooming, the birds are singing, and fast-pals Susan, Esther and Daisy continue to survive their freshman year of college. Susan is barely dealing with her recent breakup with McGraw, Esther is considering dropping out of school, and Daisy is trying to keep everyone and everything from falling apart! Combined with house-hunting, indie film festivals, and online dating, can the girls make it to second year?

The Eisner Award-nominated series from John Allison (Bad Machinery, Scary Go Round) with artist Max Sarin delivers another delightful slice-of-life adventure in Giant Days Volume 4. Collects issues 13-16.

This was a birthday gift from my auntie, and I was so excited that I read it that same day. I loved it just as much as the previous volumes. It’s highly entertaining, and I definitely consider this to be one of my favourite graphic novel series.

Rating: 4.5 Stars

Giant Days – by Non Pratt

Based on the hit graphic-novel series from BOOM! Studios, the publisher behind Lumberjanes, Giant Days follows the hilarious and heartfelt misadventures of three university first-years: Daisy, the innocent home-schooled girl; Susan, the sardonic wit; and Esther, the vivacious drama queen. While the girls seem very different, they become fast friends during their first week of university. And it’s a good thing they do, because in the giant adventure that is college, a friend who has your back is key–something Daisy discovers when she gets a little too involved in her extracurricular club, the Yogic Brethren of Zoise. When she starts acting strange and life around campus gets even stranger (missing students, secret handshakes, monogrammed robes everywhere . . .), Esther and Susan decide it’s up to them to investigate the weirdness and save their friend.

I really enjoyed this book, and was so happy when it lived up to the awesomeness of the comics. Non Pratt has done a fantastic job of writing something that can stand alone from the comics, while matching the tone of the comics, and making subtle nods to the source material.

My Review

Rating: 4.5 Stars

Giant Days: volume 5

Going off to university is always a time of change and growth, but for Esther, Susan, and Daisy, things are about to get a little weird.

Their freshman year is finally coming to a close and Daisy, Susan, and Esther say goodbye to Catterick Hall forever. Literally forever. It’s being bulldozed and re-purposed as a luxury dorm next semester. But as one door closes, another opens and between end of semester hookups, music festivals, and moving into their first home together, the life experiences are just getting started.

Written by Eisner Award nominee John Allison (Bad Machinery, Scary Go Round) and illustrated by Max Sarin, Giant Days Volume 5 finishes off freshman year in style, collecting issues #17-20 of the Eisner and Harvey Award-nominated series.

I’ve already said how much I love this series, and this volume changes nothing. It’s great. I love that they are showing the passage of time, and allowing the characters to move forward and progress through life. I’m really looking forward to finding out what the girls will get up to in their second year of university.

Rating: 4.5 Stars

Ms Marvel: volume 9 – by G. Willow Wilson, Nico Leon

Kamala Khan has vanished! But where has she gone, and why? Jersey City still has a need for heroes, and in the wake of Ms. Marvel’s disappearance, dozens have begun stepping up to the plate. The city’s newest super hero Red Dagger and even ordinary citizens attempt to carry on the brave fight in Kamala’s honor. Somehow, Ms. Marvel is nowhere…but also everywhere at once! Absent but not forgotten, Ms. Marvel has forged a heroic legacy to be proud of. But when an old enemy re-emerges, will anyone be powerful enough to truly carry the Ms. Marvel legacy – except Kamala herself?

COLLECTING: MS. MARVEL 25-30

This is another of my favourite ongoing graphic novel series’, and one of the only Marvel titles that I’m interested in keeping up with. I really enjoyed this volume. I liked that they focused on Kamala’s friends, and how they cope without her while also covering for the missing Ms Marvel. It was a lot of fun, and I can’t wait to see what happens next.

Rating: 4 Stars

Ancient Magus Bride volumes 2,3,4,5

Great power comes at a price…

Chise Hatori’s life has recently undergone shocking change. As a sleigh beggy–a person capable of generating and wielding tremendous magical power–she has transformed from an unwanted child to a magician’s apprentice who has been introduced to fae royalty. But Chise’s newly discovered abilities also mean a cruel fate awaits her.

I’m really enjoying this manga series, the anime is a pretty faithful adaptation so far, so no surprises, but I love the art, and I’m really enjoying reading the source material. I especially loved all the tiny details and explanations that weren’t in the anime, that really add to the story. I loved the anime, but I feel like I’m getting to know the characters and the world a bit better in this format, and I really like that. I love the magic, and the large, interesting world that’s being set out in these books. Also, I really like the bonus content in the collected volumes, it makes me so happy.

Ratings: 4 – 4.5 Stars

Sorry this post is a month late, I don’t know why I didn’t post it sooner, it’s been ready for a while. I’ve been such a mess this past month, I need to be more organised.

Want to chat, about books or anything else, here are some other places you can find me:

Twitter @reading_escape

Instagram: @readingsanctuary

Goodreads

Tumblr

August Reading Wrap Up I started the month in a really bad reading slump, so my main goal for the month was to get over that.

#book blog#book blogger#book recommendations#Book Review#bookish#books#bookworm#reading wrap up#Review#YA#ya books#young adult#young adult books

1 note

·

View note

Text

Top 20 Blogging Rules (I bet you are overlooking at least one rule!)

Hi Everyone,

Welcome to the round-up of the Top Twenty Blogging Rules you need to follow if you are to make a success of your blog.

Blog rule 20 is finally revealed below.

So let us begin.

Rule 1 Theme

If you cannot navigate your website then neither can your readers - Choose themes carefully.

Running a successful blog and website involves a lot of work. Here at The Go To Girls Blog we take every minute we can and make the most of it, whether it is having some downtime with our families or using the time to update our website or writing blog post ready for future posts.

If you make any changes to a theme, that lead you to believe it makes it harder to read or navigate for that matter then you must correct them. Remember If you cannot read it easily then neither can your readers!

We read a lot of books and blogs and watch videos on blogging during our research and one of the top things that lose you readers and potential customers is a website that is poorly presented.

We have got pretty good at developing our website as you can see by the results on our site.

Rule 2 Logo

The Go To Girls Blog Brand Logo Image

One thing you will find your self needing for your blog is a logo. This logo will help people recognise you and your brand across every social media app you use.

If you think about your brand when you are opening social media accounts, if you use random photos or characters then how will people know when they have found the correct account?

After all, there are plenty of copy cats out there who will use your brand to get recognition for their own. You can never stop this but you can brand cleverly by having your own logo.

The Go To Girls Blog Logo

Some established brands even copyright the logo they create for their brand. Here at The Go To Girls Blog we actually have two logos. Either of them can help readers recognise our brand and we even have them on our business cards.

Rule 3 Great photos

Bloggers who write great posts will already know what to include and what not to in their work. Following our blogging rules could help you be one of those bloggers.

#Picoftheday

One of those things we found here at The Go To Girls Blog is to ramp up the interest in your post you must include lots of good quality photos and videos. When you take photos chose the best ones, don't use blurry or badly lit photos.

Take more photos than you need as you never know when you will capture the extra special one. There are lots of places out there you can get stock photos for free but the best photos are taken by YOU!

While some bloggers do not use photos at all and some use the middle of the road photography you can make your blog stand out and keep ahead of all of your competition by just following this one blogging rule.

Rule 4 Hosting

Choosing the best host for your website and/or blog is probably the most important thing as this can determine how good your website runs and looks.

While there are lots of website hosts out there you should consider what you want from your website and host, when making this decision.

At The Go To Girls Blog we chose Bluehost to be our host as, when we read up on what we wanted from our website, Bluehost came out as the one for us.

For The Go To Girls Blog a couple of things we wanted our blog posts to look good across all platforms, so no matter if you are looking at us on your phone or your laptop the website would look amazing.

It needed to be quick and have enough tools to make sure our website was secure and protected from cyber-attacks. One of the good things about Bluehost is WordPress can be installed directly.

There are lots of different themes within WordPress so you can build the most beautiful websites through Bluehost

Have a look around our website to see all of the amazing features of Bluehost. The most important thing of all depends on you doing your homework. Read up on all hosting services and make a list of what you want from your website then you are fully prepared to make your decision.

(This post may contain affiliate links for which (at no additional cost to you) we may receive a small re-numeration from any purchases you make.)

Rule 5 Post Regularly.

The Go To Girls Blog posts every day and there is a good reason for this frequency. If you want to get a regular following posting regularly is a must.

Whether you post every day or 3-4 times a week, POST REGULARLY. It lets people know they can expect to hear from you on certain days.

One thing readers do not like is bloggers who are unreliable. Having readers who never know when or if you will post again won't come back.

If you do blog every day you must make sure you still keep up the quality of your writing though. Do not exchange quality for quantity and this will lose you readers just as quickly.

Don't forget to make sure you do the same on all of your social media too.

Keeping your brand out in the public domain means making sure it is posted regularly across all of the social media platforms you use for promoting your brand.

What is the point of writing a great post and then it stays on your laptop?

The whole point of blogging is to let as many people know about it as possible. Using social media is a proven way to advertise your post so make sure you share it around as much as possible.

Rule 6 Time Management.

Time must be the no one thing all bloggers struggle with especially If you have a full-time job as well as a full-time blog. What can you do about this? I hear you ask.

Do you have great time management skills or do you get a plugin to do it for you?

There are so many different jobs you must do to run your blog successfully. You have to find time to come up with great ideas for your blog posts, take photos, keep your website up to date as well as maintenance and updated regularly.

So time management can be time-consuming in itself. If you really want to keep on top of your time then you can always use a great plugin.

Here at The Go To Girls Blog, we use Timetable and Event Schedule by MotoPress.

This plugin is great for arranging your time into slots of various tasks plus those all-important meetings.

You can arrange the whole lot in one plugin which is good as who wants to be splitting themselves between multiple time management apps as well. If you have a Wordpress blog then give it a try.

Rule 7 Be Unique

With so many bloggers out there you have to consider what is going to make you stand out among all of the others. One thing we learned here at The Go To Girls Blog is to be ourselves when we write.

Be the unique person you were born to be. Don't join the blogger bandwagon and write the same old stuff you see day in, day out. Everyone has a different view on life all with our own back story and each with our own strengths and weaknesses.

Always play to your strengths. Write about what you know. What are you good at? What do your family and friends come to you for assistance with? I am yet to meet a person who does not have at least one skill.

We might not all value each other's skills but we have them nonetheless. We all have experiences in daily life.

We all travel, work, cook, clean, care for ourselves or others. Every one of these things can give you a very successful blog. Why? Because they are all unique to YOU!, and someone always needs help or advice on one of the millions of topics around the world.

You just need to choose which one you can help others with. BUT write about it with your own unique insight. This should help at least get you recognised for being unique and therefore more people will come to your blog.

Which means, TRAFFIC. The holy grail for bloggers. Ask any blogger what their top want/need is!

They will all say the same - TRAFFIC.

Rule 8 Use Analytics.

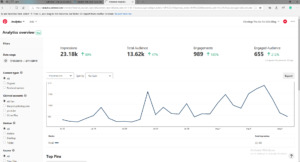

Any blogger loves to see how their website is doing across all of the social media platforms and especially their blog. To do this you need to have some form of analytics to record things like how many followers you have across all of your social media platforms.

Pinterest Analytics

Pinterest Analytics

What method people used to find your site, did they search Google or did they click a link in Pinterest? How many pageviews a day do you have and even how much time on any given page within your posts or website. I know it sounds amazing doesn't it that you can actually see all of this information.

Well, you can and I can tell you it becomes quite addictive. Watching how many visitors you have on the blog you just posted, tracking daily figures to determine the growth of your blog.

It feels great when you see one, ten, a hundred, a thousand people visited your site today and you never know when it is going to stop. Maybe it won't, maybe in a few months you will have a million views but the analytics will still remain one of the most important tools you will ever have as a blogger.

It will also help you find your audience, how old they are, what devices they are looking at your website on and even what interests they have. This may not sound like the information you want but believe me, it is!

This is the breakdown of everything you will ever know to make a success of your blog. Use it wisely and it will help you build your brand.

Rule 9 Budget.

Another rule for any blogger but especially a new blogger is don't spend money you don't have! You will see everywhere companies who want to help you with apps and plugins, themes and advertising.

While these may be ok if you have a budget they are not so great if you are on a tight or no budget at all. The truth is if you pick the right host you can rely on them to help you with some of the technical features of building your website.

Although some do not include some of the design features of your website like colors and themes. The internet and in particular YouTube is also an amazing tool in helping create a great website.

All you need is a little technical knowledge and YouTube and you can get away with little or no budget and have a beautiful website. One of the things we do here at The Go To Girls Blog is to offer assistance to new and existing bloggers' and technical help.

We know how hard it is to get your website up and running especially when you are right at the beginning of the process.

If you find yourself in need of a bit of technical help then drop us an email and depending on the nature of your query we may be able to help for free (in more complicated cases there may be a small charge)

But we will help you on your way to getting your website looking beautiful and your blog running smoothly.

Rule 10 SEO or Search Engine Optimisation.

Something to consider when writing a blog or creating a webpage is how it is going to appear on the internet, in particular within search engine results.

Nobody wants to spend all the time they have creating content and then not appear in any searches. Everyone wants their posts and website to appear on the first page of Google search and this is attainable.

You just have to optimise your post for this. SEO or Search Engine Optimisation is maximising blog posts or website pages chances of appearing high on search engine searches and therefore getting more traffic for your brand. As I said in a previous post traffic is key to a successful blog/website/brand.

Here at The Go To Girls Blog we use a couple of SEO Plugins. Why use more than one I hear you ask? Well, I thought long and hard about this and I came up with this, one SEO plugin told me to do certain things to my blog like use internal links and image tags.

Then just out of curiosity I installed another one and that told me a totally different list of things that would 'optimise' my post, like use a focus key phrase and set the width of my title to so many characters. Confusing, Yes! Or is it? Could it be more useful information on search engine optimisation?

We thought what if we try to follow the suggestions on 2 of these SEO plugins and see what happens. So we did and guess what happened?

WE GOT TRAFFIC TO OUR SITE!

It actually works.

We use On-Page and Post SEO and Yoast SEO.

Why not give them a go, it can't hurt your brand but it can make the world of difference to your website.

Rule 11. Appreciate Interaction.

When you are a blogger one thing that makes your day is when your readers and followers interact with you. This can be by following you, leaving a comment, linking to your blog or simply liking your latest work.

Whatever the interaction, make the most of it. If someone comments on your work then reply and whether it is positive or negative. If it is negative just take it on the chin.

You chose to put your work out there on the internet for all to see and you will find that whatever you write it will not be everyone's 'cup of tea'.

If someone writes a negative comment thank them for their opinion and leave it at that. Other bloggers may ask you for help if you can then help them, DO SO! Interaction is key!

You will be surprised how far answering a question (which may be easy for you to answer) will take you with regard to your reputation as a good blogger.

Other bloggers will always appreciate interaction whether it is a bit of help or advice when they need it. Don't forget not all bloggers are 'techie' or good at all aspects of bogging so you never know what help a fellow blogger will ask for.

Here at The Go To Girls Blog we get asked all sorts of questions from what hosting do we use? to how do we center ourselves when we write? We always reply with as much information as we can.

Rule 12. Teamwork.

There are so many different jobs you need to have covered when you are running a successful blog which could make it impossible to do alone. With this in mind, you are going to need an amazing team of very skilled people. Just to name a few roles you need to fill are a web designer, a social media manager, a photographer, and a writer.

When we started we did not have any of these roles here at The Go To Girls Blog there were just two of us. Now we have a few more people helping out with all of the various jobs we have to do daily. I can tell you it feels great not having to fit in all of these roles ourselves.

Directing all of these amazing people is so much simpler than doing it all your self. The one thing we noticed is the teamwork aspect of our job has just transitioned from managing time to managing our team.

Great teamwork is key! Everyone who has ever worked in a team will know not only do you need a team with the right skills for the job, they also have to have the right personality for your team.

Here at The Go To Girls Blog our team fits perfectly together. Everyone knows the importance we place on teamwork and we like to have a laugh but we all know when it is time to get our heads down and get to work too. Our team all work really hard and are always ready to put in that bit extra when it is needed.

This has also helped The Go To Girls Blog expand into helping other fellow bloggers who contact us regularly for help with various queries about their blogs. If you find your self in need of any help drop us an email at [email protected] or use our contact us link on the website. We are always here to help.

Let us know your stories about teamwork whether it is a small or large team, we would love to hear all about it.

Rule 13 Use Links.

When writing a blog post you will hear people recommend that you use 'links'. Well, this is ok, if you know what they are and how to use them. What they are for is another thing you will need to understand.

Firstly to explain a link is a way bloggers can direct traffic to other posts whether they are their own or other bloggers. This is a great way of getting other posts and bloggers traffic which may have a similar topic or niche.

Linking to other bloggers is also a great way to make blogger friends and building your blogger community. Using them is relatively easy as on most platforms the symbol for links is recognisable.

link