#wielder of the flame of Anor. The Dark Lord will not avail you

Text

ALSO UNLETARED, BUT SPEAKING OF FANTASY AU's, My case for Kyoya being Boromir in a Lord of the Rings AU:

Ngl, would be tempted by The Ring, and try to take it from whoever is Frodo

The "Who is this up-start Gingka son of Ryo, the elfs are claiming as the 'True King of Gondor', my family has been running this country for centuries" to "I would have gone with you to the end" pipe line is real, whether Kyoya wants to admit it or not

Devine shield, aka protector of the realms of Men?

Kakeru can be Faramir, ridding his bike horse up and down Ithilien

Tackled by a bunch of Halflings

#idk I had thoughts at midnight and now I have written them down in a tumblr post#special move: rambling#don't really know who else is who except Kakeru as Faramir and Gingka as Aragorn#and maybe Kenta Yu and Tithi being the hobbits#if Kenta is Frodo would Ryuga then be Gollum?#That does NOT fit his character lmao#idk maybe him and Kenta should be in the Hobbit instead#Also ngl Ryo pulling “You shall not pass! I am a servebt of the secret flam#wielder of the flame of Anor. The Dark Lord will not avail you#Flame of Udun! Go back to the shadow#and when dying in a cave in#BUT coming resurrected#Good stuff#but would not work with Gingka being Aragorn#eh#I am sure if I squint hard enough I can find parallels everywhere#good night folks

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edmure's Gandalf moment:

Lord Tywin had tried to force a crossing at a dozen different fords, her brother wrote, but every thrust had been thrown back. Lord Lefford had been drowned, the Crakehall knight called Strongboar taken captive, Ser Addam Marbrand thrice forced to retreat . . . but the fiercest battle had been fought at Stone Mill, where Ser Gregor Clegane had led the assault. So many of his men had fallen that their dead horses threatened to dam the flow. In the end the Mountain and a handful of his best had gained the west bank, but Edmure had thrown his reserve at them, and they had shattered and reeled away bloody and beaten. Ser Gregor himself had lost his horse and staggered back across the Red Fork bleeding from a dozen wounds while a rain of arrows and stones fell all around him. "They shall not cross, Cat," Edmure scrawled, "Lord Tywin is marching to the southeast. A feint perhaps, or full retreat, it matters not. They shall not cross."

A Clash of Kings, Catelyn VI

The Balrog reached the bridge. Gandalf stood in the middle of the span, leaning on the staff in his left hand, but in his other hand Glamdring gleamed, cold and white. His enemy halted again, facing him, and the shadow about it reached out like two vast wings. It raised the whip, and the thongs whined and cracked. Fire came from its nostrils. But Gandalf stood firm.

'You cannot pass,' he said. The orcs stood still, and a dead silence fell. 'I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass.'

The Fellowship of the Ring, The Bridge of Khazad-dûm

That's all.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Balrog reached the bridge. Gandalf stood in the middle of the span, leaning on the staff in his left hand, but in his other hand Glamdring gleamed, cold and white. His enemy halted again, facing him, and the shadow about it reached out like two vast wings. It raised the whip, and the thongs whined and cracked. Fire came from its nostrils. But Gandalf stood firm.

'You cannot pass,' he said. The orcs stood still, and a dead silence fell. 'I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass.'

...

From out of the shadow a red sword leaped flaming.

Glamdring glittered white in answer.

There was a ringing clash and a stab of white fire. The Balrog fell back, and its sword flew up in molten fragments. The wizard swayed on the bridge, stepped back a pace, and then again stood still.

'You cannot pass!' he said.

...

At that moment Gandalf lifted his staff, and crying aloud he smote the bridge before him. The staff broke asunder and fell from his hand. A blinding sheet of white flame sprang up. The bridge cracked. Right at the Balrog's feet it broke, and the stone upon which it stood crashed into the gulf, while the rest remained, poised, quivering like a tongue of rock thrust into emptiness.

With a terrible cry the Balrgo fell forward, and its shadow plunged down and vanished. But even as it fell it swung its whip, and the thongs lashed and curled about the wizard's knees, dragging him to the brink. He staggered and fell, grasped vainly at the stone, and slid into the abyss. 'Fly, you fools!' he cried, and was gone."

-Lord of the Rings, JRR Tolkien

4 notes

·

View notes

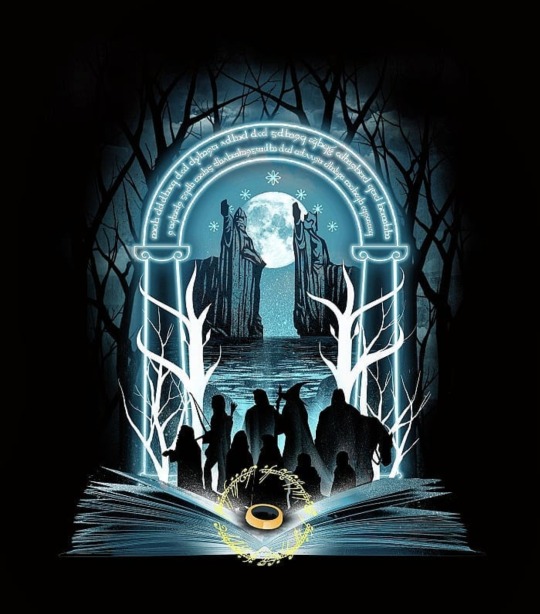

Photo

“ You cannot pass! I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the Flame of Anor. The dark fire will not avail you, Flame of Udun! Go back to the shadow. You shall not pass! “

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

0 notes

Photo

Dueling Magic Systems

In our very first lesson (find it here), I pointed out that readers of fantasy crave tales with a strong sense of wonder. That’s why many editors seek stories that have a high level of magic. In short, magic happens frequently. But you might notice that if you only have one magic system in a story, one way of creating wonder, the level of wonder in the story will begin to wane, and as your single magic system becomes better understood by the reader, it might begin to feel . . . stale—not quite as wondrous as it did when you began. So authors very often juggle multiple magic systems in a single story. Making better magic systems is difficult, but how do you juggle more than one?

For example, if you look at J.K. Rowling’s books, every few pages she introduces a new spell or new type of magic. Is her magic cast only with wands? No. She has some places where a simple spell might be cast using only an incantation, without the amplifying power of a wand. In other places, magic is cast using potions or enchanted objects. In other places, we have various creatures that have their own magical abilities.

A similar thing happens in Lord of the Rings, where each race seems to have its own magical gifts. Sauron’s magic seems to be his alone, and Gandalf with his wizardry and the elves with their own lore seem unable to withstand his powers. Only Tom Bombadil, with his own innate magic, seems unaffected by Sauron’s will. But in a parallel similar to Rowling, we see various manifestations of magic in herbal lore, enchanted items, and magical creatures. Indeed, when Gandalf confronts the Balrog and claims to be the wielder of the “secret fire,” the flame of Anor, to the Balrog he warns, “The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn.” Thus he claims to be a servant to a higher power, not just a power in himself.

We can of course go back to classic tales and find similar uses of multiple magic systems in a high-magic tale. We can see it in things like Homer’s The Odyssey, or in the Mayan Popol Vuh,

Not only do some tales have high magic levels where there is a great deal of magic and low magic levels where there is practically no magic at all, there are magic systems that are “hard” or “soft.”

A hard-magic system is one where the magic system is concrete, well developed, and has defined rules and limits, as in Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn series. A soft magic system is one where the rules are nebulous and unclear, perhaps even to the author.

Now, even a low-magic system can induce a sense of wonder, and some great works make use of this. For example, let’s go back to what Gandalf was saying. As a servant of the secret fire, what exactly were his powers? I’m not sure that even Tolkien really knew. He never tells us the rules of this magic system, how it was used or mastered. Thus, Tolkien made good use of nebulous magic systems, and even Galadriel seems unsure of what humans call magic.

In fact, we don’t often see novels where two or more hard magic systems are put in competition, where wizards from different schools of magic for example find themselves at odds. I played with this in my Runelords series by having Gaborn torn between the rune magic used by his forefathers and the far older “earth magic” used by wizards in his world, but I have to admit that the rules of earth magic in my system aren’t as “hard” as those found in the rune system. After all, the earth grants powers to those who serve it, and those powers seem to differ based upon the wizard's calling and needs.

Instead of multiple hard magic systems, a lot of authors will develop one magic system well—the one that the protagonist must master—but will have various other magical wonders sprinkled throughout. Thus we see Harry Potter struggling to master wand magic, but at the same time we see him visit a haunted loo, deal with magical artifacts like talking photographs, while dueling against other softer magics.

Why are some magics soft? Usually because the protagonist has no firsthand knowledge of the system. Frodo doesn’t understand how the dwarves create their magical implements. Do dwarvish swords not rust or grow dull because of incantations or is it simply that they have created new types of hardened metals that don’t suffer the fates of simple iron? I suspect that what Frodo perceives as magic, a metallurgist would see as science. Yet within the context of the story, dwarven blades still arouse a sense of wonder. And in much the same way, Galadriel doesn’t talk about her magical ropes as being “magic,” but calls the wonders “well made.”

So, how do you add new wonders to your story? In designing role-playing and video games, we see a lot of possibilities. For example, you can add wonder to a tale by creating “Points of Interest.” These can be places that have a fascinating history, but often which also have some sort of magic associated with them. Thus we have haunted swamps, powerful magical wards, healing pools, and so on.

The same kinds of wonders can be associated with various species of creatures. In a game, for example, we might give magical speed to a horse, or fire-breathing powers to a monster, or strength to a certain class of fighter, or the ability for a tree to make travelers fall asleep while its roots slowly entangle them.

And of course we might imbue various artifacts with similar magical powers.

As a writer of fantasy, one goal is to simply make the tale as fun as possible!

Enjoy your writing this week!

-David Farland

#writing#writer#writingtip#writingtipsandtricks#writinglesson#writingadvice#writinghelp#author#editor#writerblr#fanfiction#nanowrimo#writingabook

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

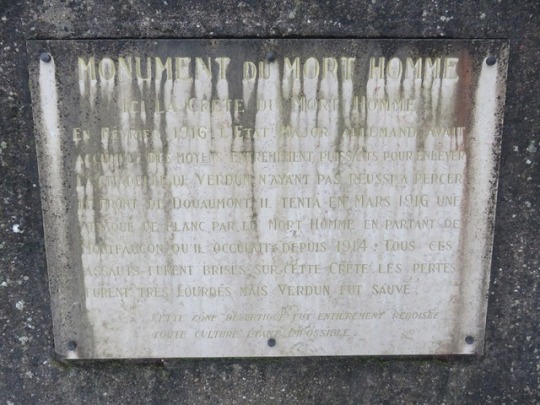

Monument Le Mort Homme, Chattancourt France, December 2018.

Full photo gallery online here.

Monument Le Mort Homme

The scene of ferocious fighting during the Battle of Verdun, Le Mort Homme (The Dead Man, named before the Great War began curiously enough) lost 35 feet in overall height due to the amount of artillery fire that took place between the French and Germans. The ground still bears the pockmarked evidence of the shell explosions despite being covered by Austrian pine trees that were planted in the 1930’s (strong enough to withstand the toxic soil, poisoned by the remains of battle). The Germans took this hill in May of 1916 and, despite constant fighting, it was not taken back by the French until August 1917.

There are two prominent memorials at the top of the hill. The smaller of the two, an obelisk with an engraved sword to commemorate the French 40th Division. The other, a large skeleton holding the French flag and a torch, a commemoration of the French 69th Division. “ILS NONT PAS PASSE” (They Did Not Pass), in reference to French General Robert Nivelle’s inspiring June 23 1916 order of the day (Ils ne passeront pas!), is inscribed on the base of the monument. Author J.R.R. Tolkien, serving at the Somme in July of 1916, may have been aware of Nivelle’s order and, along with other experiences from the Great War, might have used this bit history when writing Gandalf’s equally inspiring words in his 1954 Lord of the Rings – Fellowship of the Ring:

You cannot pass," he said. The orcs stood still, and a dead silence fell. "I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass.

It was a snowy, foggy and icy drive to get to this place. It was very quiet, I was the only one stupid enough to be at the top of this hill on such a miserable day, but the weather seemed appropriate for the location. It would have been interesting to explore the woods a bit, but there was no path and who knows what unexploded munitions are still in the ground up there.

February 22, 2019

#morthomme#verdun#france#greatwar#firstworldwar#worldwar1#nivelle#tolkien#lordoftherings#youcannotpass

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

'You cannot pass! I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the shadow! YOU!! SHALL NOT!! PASS!!'' - Gandalf the Grey Nu in pre order van Prime1 Studios Lord Of The Rings: Gandalf Vs Balrog Diorama . Zoekcode op onze webshop P1SPMLOTR02 #gandalfthegrey #tolkienfan #jrrtolkien #lotr #tolkien #fellowshipofthering #gandalf #thelordoftherings #lordoftherings #middleearth #thehobbit #tolkienart #gandalfthewhite #balrog https://www.fanssite.be/lord-of-the-rings-gandalf-vs-balrog-diorama.html (bij FANS-shop) https://www.instagram.com/p/CCppYHgHg1l/?igshid=ctsssmi3i4cm

#gandalfthegrey#tolkienfan#jrrtolkien#lotr#tolkien#fellowshipofthering#gandalf#thelordoftherings#lordoftherings#middleearth#thehobbit#tolkienart#gandalfthewhite#balrog

0 notes

Photo

""You cannot pass," he said. The orcs stood still, and a dead silence fell. "I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass." —The Lord of the Rings @theancientforge #lordoftherings #lordoftheringscosplay #lordoftheringstrilogy #lordoftheringsonline #lordoftheringsrp #lordoftheringsquote #lordoftheringsfan #lordoftheringsnerd #lordoftheringsmarathon #lordoftheringslegolas #lordoftheringsmovielocations #lordoftheringsphotoshoot #lordoftheringsshit #LordOfTheRingsStyle #lordoftheringsart #lordoftheringstour #LordOfTheRingsGame #lordoftheringsswords

0 notes

Video

youtube

"You cannot pass," he said. The orcs stood still, and a dead silence fell. "I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass."—The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring, Book II, Chapter 5: "The Bridge of Khazad-dûm"

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding THE LORD OF THE RINGS

The Lord of the Rings has already inspired two blog-like posts from me: one, written on a particularly nostalgic day, chronicles the most tear-jerker moments of the trilogy and the other, my review for The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies, served not just as a critical analysis of that film, but I used the Lord of the Rings trilogy as a consistent counterpoint to illustrate why those films are so seminal. I note these two pieces to emphasize this point: Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy is a monumental cinematic achievement in my eyes, and greatly shaped my appreciation for film and its possibilities. They’re simultaneously well-honed adventure epics and brimming with hints of former lore -- of a history that has shaped the world we get to see. Having taken The History of Middle-earth course, those gaps are now filled, and my appreciation and comprehension of Tolkien's world is far more complete than it was before.

The portrayal of Middle-earth in the films is one of decay, of a bygone era long-crumbled, and the remnants are now scattered kingdoms filled with weak or illegitimate leaders. This is clear from the first viewing of these films, and I always understood that there was a rich history behind these images. The film consistently brings them up: Aragorn sings of the Lay of Lúthien, Frodo and Sam happen upon a decapitated statue of a king, Gandalf warns “they are not all accounted for -- the lost seeing stones” -- the only backstory we get of the Palantíri. Indeed, even things we are shown in the prologue are only given so much information. Viewers have no idea of Mordor’s history -- was it always there? Has Sauron always been a plague on Middle-earth? Where did he come from? And little is told of Valinor, the land Frodo sails off to in the end, the land Gandalf gorgeously describes to calm Pippin during the siege of Minas Tirith.

The Silmarillion tells us of before Earth (or Arda) is even created, how the beings that helped shape it reside in Valinor across the western sea. From it we have better descriptions of Valinor than the poetry Gandalf musters, and we understand the Valar themselves -- their limitations of understanding, their unique desires to see different aspects of Arda to fruition, and the thousands of years of history that explain why Valinor is such a coveted destination -- and a particularly impossible one for the race of Men.

That’s a heavy amount of information already, but it’s enough to bring the grander vision of Middle-earth into the light. Before the course, my understanding of Valinor was that it was a Tolkienized vision of heaven; a place where you never die, you never hunger, you never feel pain. And while heaven isn’t exactly a wrong term to describe Valinor, it’s also incorrect in its lack of nuance and understanding. Valinor is a real place in Arda, a place with its own geography and names and cities. The majestic beauty of the Valar, the godlike beings who first shaped Arda and reside in Valinor, bestow upon the lands a light that gives it a heaven-like quality, but it isn’t a heaven in the religious sense.

While I always inferred a sense of ancient history to The Lord of the Rings, I had absolutely no comprehension of how far back that history ran, nor how much the geography changed since Arda’s formation. When we follow the Fellowship into the Mines of Moria, there is a sense of hundreds of years of decay, but the truth is the oldest places of Middle-earth are under the sea -- sunken from a great battle to expel evil (more on that later). Time, and just how much of it has passed and shaped the people, the world, is lost in the films. All we see are bones now; ruined monuments, frail kingdoms. Another example from Moria is when the Orc stampede awakens a Balrog. This moment is superbly done in the film and still gives me goosebumps: the music halts, stone creaks, and Gandalf for the first time has no answers except “run.” The entire following sequence has entered pop culture. But I was left to come up with my own idea of the Balrog’s origins. It seemed like the depths of Middle-earth held a powerful evil, one of the worst of which could be the Balrog. Turns out, well...

The Silmarillion describes one of the Valar, Melkor, who strayed from the light from pride and desire, and eventually sought to undermine the other Valar and rule Arda. He was the one who began to torture Elves, twist them into Orcs through cruelty (this is shown once in the films and is quite ambiguous -- another gap filled by the history). And Melkor, later named Morgoth, supplemented his armies of Orcs with legions of Balrogs. There used to untold numbers of those foes. They slaughtered Elves and Men in several wars, before the western lands sank, and they even had a leader named Gothmog (a name I suppose Jackson & Co. liked so much they donned it upon the crippled Orc leader in Return of the King). Tales of these wars, of the heroes within them, are often told in detail, and when Morgoth was finally defeated (after a very, very long time), the remaining Balrogs fled into the deeper, darker regions of the world, to hide and await the return of their master. The now-classic Khazad-dûm sequence is given layers of context from this: a creature of ancient evil, created by a Valar of all beings. No wonder Gandalf is out of options; the Fellowship doesn’t have a chance against such a creature. Moreover, when Gandalf holds the Balrog on the bridge, he says, “I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the Flame of Anor. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn.” The Silmarillion teaches us that the Secret Fire, or Flame Imperishable, is with Ilúvatar, and that Anor is another name for the Sun. Again these indications of a greater lore behind the present storytelling, but only indications -- only mentions. The Silmarillion doesn’t break down this phrase, but it does use this terminology. I could get the gist of what Gandalf was saying beforehand, but now I know exactly what he’s saying and referencing. And this adds layers to Gandalf, too. Sure, he knows what a Balrog is from the start, but now I know he’s referencing Illúvatar, the light of the Sun as provided by the Valar, and he knows the Balrog’s master, and Melkor’s first fortress Utumno. A kind of snowball effect begins to occur with the extra knowledge of this history, and soon every character feels deeper, feels more connected to a root system going back thousands of years.

Through the history, the origins of seemingly random things can be traced, thereby eliminating their randomness. Sauron, though the highest power of evil in the Third Age, was a mere lieutenant to Morgoth. And Sauron was a corrupted Maiar, a lesser version of the Valar, tasked to aid the Valar with the keeping of Arda. In the Unfinished Tales, we learn that wizards like Gandalf and Saruman are Istari, sent in the fallible form of Men in the Third Age by the Valar to help steer Elves and Men along the path of the light in the wake of Sauron’s growing influence. This was always a point of contention with pedants: “Why can’t Gandalf use magic to help them out here?” -- akin to the “Why can’t he summon the Eagles to fly them straight to Mordor?” argument. My answers, before the course, were more defense of story structure than actual answers. But it makes sense, given the history of Maiar like Sauron, that the Valar would send the Istari to Middle-earth with restrictions on their powers, lest they be tempted to rule by force or seek power. This still happens with Saruman, and so the Valar seem wise to have placed limitations on wizardly powers. But again, these answers are not clear from the films. The films don’t tell us what Maiar are, and thus Gandalf and Sauron simply are. They exist without given reasons. The history detailing the Istari not only illuminates on Gandalf and Saruman’s backgrounds, but it raises the stakes for Gandalf. His susceptibility to human weakness makes him less otherworldly, less out of place from the Fellowship, and the challenges he faces seem greater. He cannot just poof away his problems. And these sorts of things continue to show up in the histories. Ungoliant, a presumed twisted Maiar in the form of a wretched spider-beast, is pivotal in a dark moment in the ancient history of Valinor, and her appearance (without even mention of it) makes Shelob’s presence in Return of the King more acceptable (as in, it’s more than just “a giant spider monster happens to dwell in this tunnel”) and fearsome.

To the strongest point of the history’s effect on the films, I think the theme of doom and how it ripples through the timeline even to Lord of the Rings is the most compelling and rewarding for later re-watched of the films. Morgoth doesn’t start out as this vicious, evil spirit, but his slow descent from disobedience to power-hungry lust is what does it. He learns to lie, to deceive and spread half-truths, to sow evil into the hearts of (first) the Elves and (then) Men. And it reaches out from there. Countless times, a small act from Morgoth eventually incites violence, and those involved don’t even know of Morgoth’s involvement half the time. In Valinor, during the First Age, Morgoth is the catalyst for rumors of discontent among one of the Elvish clans -- the Noldor. And when Fëanor creates the Silmarils, beautiful orbs of light from the Trees of Valinor, Morgoth steals them with the help of Ungoliant. Because the Noldor have learned of deceit, learned of greed, and even learned of weapons thanks to Morgoth’s “advice,” violence and tragedy strike through Valinor as Elves attack Elves, banishments from the Valar are placed, and foul oaths are taken. The Silmarils, through the course of the First Age, bring nearly every big player in that era to their knees, and this theme of doom echoes around them -- the fate of Arda being tied to them. Fëanor, so enamored with his creations, swearing to destroy any kind of being -- Elf, Man, or otherwise -- in pursuit of the reclamation of his treasures echoes the weak will of Isildur to destroy the One Ring. Even the rings themselves are connected to Fëanor via ancestry through Celebrimbor.

This theme of all beings of Illúvatar and their weakness, their ability to succumb to power, to self-aggrandizement, to doomed desire, encircles the entire history of Middle-earth; it isn’t just unique to The Lord of the Rings. The fact that this keeps playing out again and again, in different ways, with different consequences, and yet always with grief and strife one way or another, makes those themes in The Lord of the Rings even more tragic and poignant.

#Lord of the Rings#Lord of the Rings History#the silmarillion#Morgoth#Valar#Unfinished Tales#jrr tolkien#Gandalf#Saruman#Moria#Balrog#Silmaril#Feanor

0 notes

Text

I was tagged by neferukaen

The BBC estimates that most people will only read 6 books out of the 78 listed below. Bold the ones you’ve read.

1. Pride and Prejudice - Jane Austen

2. Lord of the Rings - J. R. R. Tolkein (I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass)

3. Jane Eyre – Charlotte Bronte

4. Harry Potter Series - JK Rowling

5. To Kill a Mockingbird - Harper Lee (It ain’t fair)

6. The Bible

7. Wuthering Heights – Emily Bronte

8. Nineteen Eighty Four – George Orwell

9. His Dark Materials – Philip Pullman

10. Great Expectations – Charles Dickens

11. Little Women – Louisa M Alcott

12. Tess of the D’Urbervilles – Thomas Hardy

13. Catch 22 – Joseph Heller

14. Complete Works of Shakespeare (I’ve read Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, and Twelfth Night)

15. Rebecca – Daphne Du Maurier

16. The Hobbit – JRR Tolkien (The road goes ever on and on)

17. Birdsong – Sebastian Faulks

18. Catcher in the Rye – J D Salinger

19. The Time Traveller’s Wife - Audrey Niffeneger

20. Middlemarch – George Eliot

21. Gone With The Wind – Margaret Mitchell

22. The Great Gatsby – F Scott Fitzgerald

23. Bleak House – Charles Dickens

24. War and Peace – Leo Tolstoy

25. The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams (Time is an illusion. Lunchtime doubly so.)

26. Brideshead Revisited – Evelyn Waugh

27. Crime and Punishment – Fyodor Dostoyevsky

28. Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck

29. Alice in Wonderland – Lewis Carroll

30. The Wind in the Willows – Kenneth Grahame

31. Anna Karenina – Leo Tolstoy

32. David Copperfield – Charles Dickens

33. Chronicles of Narnia – CS Lewis

34. Emma – Jane Austen

35. Persuasion – Jane Austen

36. The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe – CS Lewis

37. The Kite Runner - Khaled Hosseini

38. Captain Corelli’s Mandolin - Louis De Bernieres

39. Memoirs of a Geisha – Arthur Golden

40. Winnie the Pooh – AA Milne

41. Animal Farm – George Orwell

42. The Da Vinci Code – Dan Brown

43. One Hundred Years of Solitude – Gabriel Garcia Marquez

44. A Prayer for Owen Meaney – John Irving (The only way you get Americans to notice anything is to tax them or draft them or kill them.)

45. The Woman in White – Wilkie Collins

46. Anne of Green Gables – LM Montgomery

47. Far From The Madding Crowd – Thomas Hardy

48, The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood

49. Lord of the Flies – William Golding (Poor Piggy)

50. Atonement – Ian McEwan

51. Life of Pi – Yann Martel

52. Dune – Frank Herbert

53. Cold Comfort Farm – Stella Gibbons

54. Sense and Sensibility - Jane Austen

55. A Suitable Boy – Vikram Seth

56. The Shadow of the Wind – Carlos Ruiz Zafon

57. A Tale Of Two Cities – Charles Dickens

58. Brave New World – Aldous Huxley

59. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time – Mark Haddon (I want my name to mean me.)

60. Love In The Time Of Cholera – Gabriel Garcia Marquez

61. Of Mice and Men – John Steinbeck

62. Lolita – Vladimir Nabokov

63. The Secret History – Donna Tartt (Beauty is rarely soft or consolatory. Quite the contrary. Genuine beauty is always quite alarming)

64. The Lovely Bones - Alice Sebold

65. Count of Monte Cristo – Alexandre Dumas

66. On The Road – Jack Kerouac

67. Jude the Obscure – Thomas Hardy

68. Bridget Jones’s Diary – Helen Fielding

69. Midnight’s Children – Salman Rushdie

70. Moby Dick – Herman Melville

71. Oliver Twist – Charles Dickens

72. Dracula – Bram Stoker

73. The Secret Garden – Frances Hodgson Burnett

74. Notes From A Small Island – Bill Bryson

75. Ulysses – James Joyce

76. The Bell Jar – Sylvia Plath

77. Swallows and Amazons - Arthur Ransome

78. Germinal – Emile Zola

19/78

The BBC need stop being so cynical, everyone should read these classics. Can’t be bothered to tag anyone, do it if you see it and feel like it.

#might've had a bit too much fun doing this#Not a single damn Lovecraft book on this list though?#Also some of these I hardly remember atall.

0 notes