#wrongfully convicted

Text

Kathleen Folbigg's children most likely suffered from various genetic conditions that led to their deaths. Folbigg was wrongfully imprisoned in 2003 and ordered to serve a minimum of 25 years for the suffocation murders of three of her children and manslaughter for the fourth.

source 1

source 2

source 3

#destiel meme news#destiel meme#world news#news#tw death#tw child death#kathleen folbigg#is true crime not allowed to tag?#<- thats my true crime tag i guess#australia#wrongfully imprisoned#wrongfully convicted#acquittal

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ledell Lee (July 31, 1965 – April 20, 2017) was an American man convicted and executed for the 1993 murder of his neighbor, Debra Reese. He was convicted in 1995 and the Arkansas Supreme Court affirmed the conviction in 1997, but numerous questions have been raised about the justice of his trial and post-conviction representation. Issues have included conflict of interest for the judge, inebriation of counsel, and ineffective defense counsel. A request to postpone the execution in order to test DNA on the murder weapon was denied by a circuit judge. After Lee's execution, it was proven that the DNA on the murder weapon belonged to another person, an unknown male.

Controversy over judge's conflict of interest

According to the ACLU:

Additionally, Lee was tried by a judge who concealed his own conflict of interest: an affair with the assistant prosecutor, to whom the judge was later married. Mr. Lee's first state post-conviction counsel introduced the evidence of the affair by calling the judge's ex-wife, who testified about the affair after opposing the subpoena. That lawyer, however, was so intoxicated at the hearing that the state moved for him to be drug tested after he slurred, stumbled, and made incoherent arguments. The inebriated lawyer also represented Lee briefly in federal court, where he raised the important claim that Lee was ineligible for execution because of intellectual disability. Lee won new proceedings because of the lawyer's drunkenness, though his representation did not improve afterward. His next lawyers failed to introduce evidence of the affair, giving up one of many of Lee's important arguments, and never pursued his innocence or intellectual disability claims.

"This is a story of the judicial process gone totally wrong," Lee's lawyer said. "The kinds of attorney failures here: an affair with the presiding judge by the prosecutor, gross intoxication by defense counsel, and wild incompetence undermine our profession as a whole. Mr. Lee has never had the opportunity to have his case truly investigated, despite serious questions about guilt, and his intellectual disability."[11][5]

Throughout the legal challenges, the family of Debra Reese hoped that the execution would go through as scheduled.

HE WAS INNOCENT

#ledell lee#african#african american#kemetic dreams#wrongfully convicted#death penalty#judge#justice system#debra reese#legal#lawyer

342 notes

·

View notes

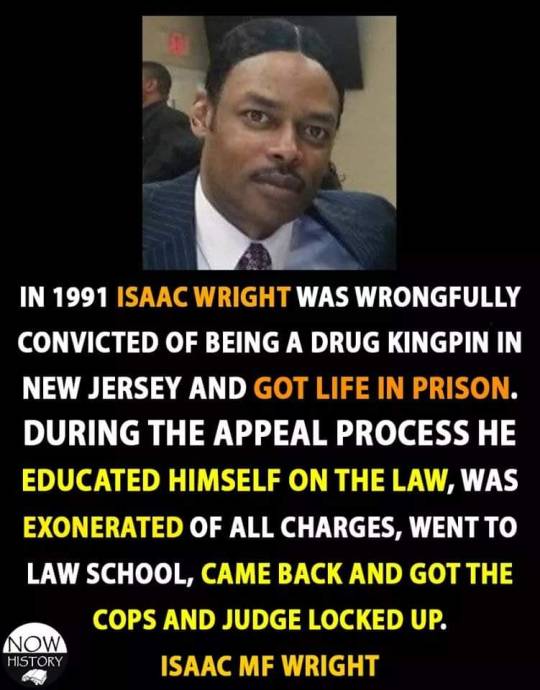

Text

#issac wright#wrongfully convicted#black history#civil rights#black literature#black community#law school

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

you number one fan-- a messy girl, in a messy room, bound to an old love who cant let go and let her live her truth.... but what will the gods do now... that this truth has been unveiled...

#jealous#envy#evil eye#truth teller#protected#wrongfully convicted#trust#truth#pink aesthetic#slim waist#hips dont lie

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The Fatal Police Shootings That Don’t Make Headlines

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Believes Kyoshk Is Innocent,” Toronto Globe. April 24, 1912. Page 2.

----

REV. MR. RIGSBY CONVINCED BY INDIAN’S STATEMENT - NOW INVESTIGATING

----

(Special Despatch to The Globe.)

Sarnia, April 23. - The police here are investigating a new theory in the Walpole Island murder, for which Stephen Kyoshk, a twenty-year-old Indian youth, has been sentenced to hang. The latest developments may remove the stain of guilt from the young man and place it on another Indian.

Kyoshk has stated to his minister, Rev. Mr. Rigsby of the Sarnia Reserve, some very important facts. The blame is put on a neighbor, and the authorities are investigating.

The prosecution in the case claimed that a repeating shotgun was used, but from the facts brought out to-day it has been proven that the shells provided could not have come from such a weapon.

#sarnia#walpole island#walpole island first nation#murder#murder trial#wrongfully convicted#sentenced to be hanged#death sentence#capital punishment#first nations#indigenous people#history of crime and punishment in canada#crime and punishment in canada#bkejwanong#anti-indigenous racism#armed with a shotgun

1 note

·

View note

Text

Struggling for justice is a fruitful endeavour.

—Ady Barkan

0 notes

Text

#louis scarcella#shawn williams#detective misconduct#coerced testimony#wrongful arrest#wrongfully convicted

0 notes

Text

#petfinder#catfinder#cat#kitten#kitty#burgle#black tuxedo#nj#new jersey#mod note: wrongfully convicted !!!!!!!!

537 notes

·

View notes

Text

remus with abs is so funny to me like that man has never worked out in his life. he used to excuse and lie his way out of PE, like one week he has a cold the next he forgot his trainers and the next he has period cramps

#remus loser lupin#overcooked noodle boy with a soft tummy#remus lupin#the only reason he would ever run is away from sports#or from his problems#or towards sirius when he suddenly shows up after 12 years of being a wrongfully convicted mass murderer

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyone ever think about how in season one of the flash they had their superhero maintain an extrajudicial prison in his basement made up entirely of solitary confinement and then when a guy broke them all out they acted like he was the asshole in that situation

#constantly crazy to me how they made barry my dad was wrongfully convicted of murder allen a firm believer in the system#coldflash are so interesting because barry so easily could have been just like len and vice versa#why didn't they ever do anything interesting with that dynamic#i know its because it's on the cw but still#the flash

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

so excited to meet prosecutor blackquill he sounds like he's got some poor little meow meow ass bullshit going on

#i sense an edgeworth 2#wrongfully convicted guy with a guilt complex who's prosecuting to punish himself?#we'll see#ace attorney#dual destinies liveblog

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Seeing how greatly interested the convicts were in the Christian Herald, I obtained permission from the warden to secure their subscriptions for it. Several hundred prisoners became subscribers and regular readers. In many instances the influence of this religious journal upon the convicts became very noticeable.

Among the subscribers was a full-blooded young Indian, of the Mohawk tribe, and known as “Indian Joe.” He was accused of having killed a man in a riot among the miners in the coal fields. Although he steadfastly maintained his innocence of the crime for which he was sentenced, he took his imprisonment with true Indian stoicism.

In his cell he kept an unique home-made calendar. On a large piece of cardboard he had drawn a great number of circles, with twelve circles in a row. Each circle stood for a moon, or month, and each row represented a year. It was the Indian calendar. As time elapsed, month by month, he marked off a circle. When all the moons on his calendar had waxed and waned, and were marked off, his long sentence would be at an end. It was a joyous ceremony to him each month when he marked off a passing moon, bringing him one step nearer to ultimate freedom.

Indian Joe was greatly pleased and perplexed as he read the Herald—pleased with the ideals of Christian living as it was taught, and perplexed by the many un-Christian acts of life as it was lived.

I was very much interested in the reactions of his alert and practical mind. One day, while talking with him about such matters, he asked me, ‘‘How come Christian folks send missionaries to China, and keep innocent white men and Indians locked up in pen right here home?”

Needless to say I was puzzled about what kind of an answer to give him, but, finally, I explained that Christian people did not know that these prisoners were innocent.

His practical mind flashed back a question immediately. “Then why no tell them?” he asked sincerely."

- Earl Ellicott Dudding, The Trail of the Dead Years. Edited by William Winfred Smith. Huntington, West Virginia: Prisoners Relief Society, 1932. p. 100-101

#life inside#west virginia penitentiary#moundsville#sentenced to the penitentiary#west virginia#american prison system#prisoner autobiography#history of crime and punishment#research quote#prison conditions#trail of the dead years#reading 2024#religion in prison#indigenous people#american indians#wrongfully convicted#christian mission#mohawk

1 note

·

View note

Text

One of these days I'm going to go on a ramble about how much I love Nina's apparent friendship with Eddy and none of you can stop me 🙂

#✧・゚:*𝐿𝑜𝑜𝓀𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝒻𝑜𝓇 𝒞𝑜𝓂𝑒𝓉𝓈*:・゚✧ - Random Thoughts#|| wrongfully convicted capoeira mans meets intentional criminal womans w near vigilante like motives#|| all bc devil mans hired both of them to put up w him & be his bodyguards / army leaders#|| they trade prison stories amid what did our boss do now stories 😔💜#|| even if Eddy's T8 story somehow puts a wrench in the idea - I will go canon divergent if I have to. Harada this is a threat.#|| Their friendship is the only semi wholesome canon content I get w my girl and thus this is my hill c':#|| I will T pose. I will gatekeep gaslight girlboss you watch me.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

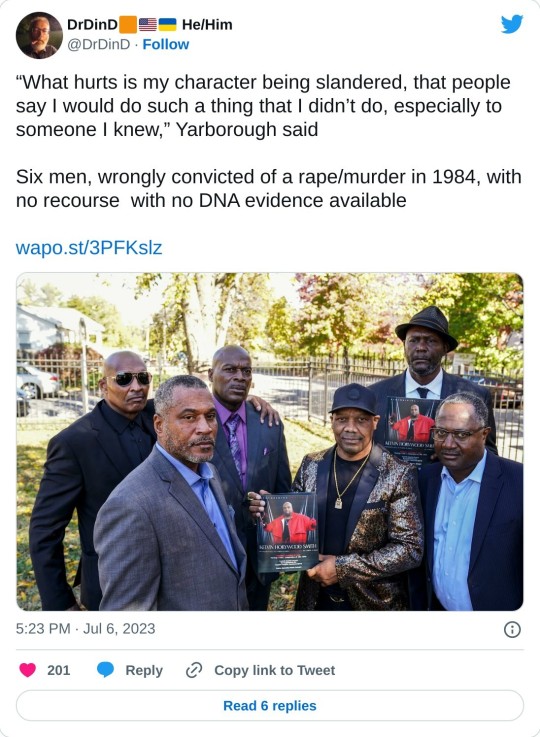

From left: Charles Turner, Timothy Catlett, Levy Rouse, Chris Turner, Russell Overton and Clifton Yarborough, attend the funeral for their friend Kelvin “Hollywood” Smith on Oct. 27 in Capitol Heights, Md. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

https://wapo.st/3PFKslz

Clifton Yarborough patted his chest as he turned his gray Honda into a narrow alley in Northeast Washington. “My heart racing fast,” he said. He eased the car to a stop and pointed to a garage behind a rowhouse. “That’s it,” he said. “That’s where it happened.” There was graffiti on the weathered plywood door. Otherwise it looked ordinary. There was nothing to indicate what had unfolded in the small structure 39 years earlier.

The alley in the H Street neighborhood is around the corner from the home where Yarborough, 56, grew up, but this is the first time he has been here since he was a teenager. He didn’t want to stay long. He put the car into drive and pulled away from the place where a 49-year-old mother of six from the neighborhood was found dead in 1984, the victim of a brutal beating and rape.

Then 16, Yarborough was the youngest of 17 people arrested in the case. He and seven other young men from the neighborhood would eventually be tried, convicted and incarcerated for a combined 258 years. Justice, it seemed, was served.

But the men have insisted all along that they had nothing to do with the rape and the murder. That they didn’t know anything about those crimes. That their trial wasn’t fair.

Kelvin Smith, who served 35 years before being released in 2019, died at home in October. Steven Webb died in prison in 1999 after a stroke. He had served 15 years. The other six men — Yarborough, Christopher Turner, Charles Turner, Timothy Catlett, Levy Rouse and Russell Overton — are now in their 50s and 60s.

They have completed their sentences and been released from prison. The final one got out just last year.

But this ghastly crime hangs over them. They are free, but not free.

What they want, they say, is for their names to no longer be associated with one of the most vile crimes in Washington history. And they want the government that prosecuted and jailed them to admit it was wrong for not sharing evidence they believe would have helped them prove their innocence.

All of the men now live in Washington or its close-in suburbs. They have jobs — forklift driver, maintenance worker, parking lot attendant, janitor, warehouse worker.

They have reconnected with their families and friends and are trying to shape a new life in a city and world that has changed immeasurably from the city and world in which they grew up. Their newly free lives are dominated by thoughts of what they’ve lost and what they can still salvage.

“What hurts is my character being slandered, that people say I would do such a thing that I didn’t do, especially to someone I knew,” Yarborough said. “Clear this. Make it be known we didn’t commit this crime.”

Rouse says it is hard for him to trust anyone. He was 19 when he was arrested and had a newborn son,whom Rouse wouldn’t see in person until his release in 2019.

“I wrote letters to him a lot, and when he grew older he would write me back, saying — Dad, I know you’re innocent and I’m always going to love you,” Rouse said. “It hurts me inside to know he had to go through that.”

Rouse says he and his 39-year-old-son are now the best of friends, making up for time they were apart.

Since getting out of prison, Rouse has focused on moving forward.Now a maintenance worker, he has completed computer courses from a career training school. He also counsels other former prisoners who have recently been released. And in September, he got married. “It’s wonderful, wonderful,” Rouse said. “Best thing that ever happened to me.”

But even as he looks forward, Rouse can’t let go of the past. “It’s important the truth comes out because they know they was wrong,” he said.

Charles Turner lives at brother Christopher’s apartment in Southeast Washington. He has a full-time maintenance job at the Martin Luther King Jr. library in downtown Washington. He’s determined to reclaim his time.

“They took 36 years from me, so I plan to be out here alive for another 36 years,” Turner said. “I’m gonna get those 36 years back.”

Turner, 59, said he feels cheated that he was locked up when his mother died and that he couldn’t say goodbye to her. And he laments never having children.

“Being locked up, they took my bloodline,” he said. “No one is gonna ever know I was even here.”

Christopher Turner, nicknamed “the Mayor” by other defendants, was the first to bereleased. He was given a shorter sentence than the others because he had completed high school and had no criminal record. In prison, he spent much of his time reading and learning about the law. While incarcerated and in the years since his release in 2010, he has led the effort to clear his name and those of his fellow defendants.

Along the way, Christopher Turner has also become an advocate for prisoners. He is on the board of the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project, which works to prevent and overturn convictions of innocent people, and Free Minds, a D.C.-based book club and writing workshop for incarcerated youths.

The men’s effort to continue lobbying for their innocence while reentering the workforce and reconnecting with their families and their city, Christopher Turner admits, is wearying.

“I know the guys are really tired,” he said recently over breakfast at a Capitol Hill diner. “We’re trying to move on with our lives. But this is still a fight we need to fight. As long as there’s air in my body, I’ll continue to fight.”

The men compare their case to that of the Central Park Five, the five teenagers from Harlem who were convicted of the 1989 rape of a woman and spent years in prison before DNA evidence and a confession led to their convictions being overturned in 2002.

But this murder occurred before the use of DNA in solving crimes began, and no evidence that can be tested survived. And unlike the Central Park case, no one else has come forward to admit guilt.

Over the years, the men have unsuccessfully appealed their convictions.

In 2017, at the Supreme Court, their attorneys argued that prosecutors violated the Brady rule by not turning over evidence to the defense. The court ruled 6-2 that the withheld evidence would not have made a difference in the outcome of the case. After that decision, the men were out of options.

But their attorneys and some of the most powerful law firms in Washington have stuck with them.

“I wouldn’t represent them if I thought they had any involvement in this whatsoever,” said Shawn Armbrust, executive director of the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project and Christopher Turner’s attorney. She has been working with the defendants since 2005. “Our standard is — you can’t have any involvement in the crime. If we find evidence pointing to guilt, we’re done.”

But there are no legal appeals left to file. No courtroom arguments left to make. No witnesses left to cross-examine.

For the defendants and their attorneys, their only hope may be a presidential pardon. And that, all of them acknowledge is, a long shot.

Crime was a problem in Washington in 1984, especially in the busy, blue-collar corridor of H Street NE. Murders in D.C. were nowhere near the astronomic levels they would climb to in the late 1980s and ’90s, but they weren’t rare either.

Among them, one murder stood out: The Oct. 1, 1984, killing of Catherine Fuller.

Fuller was 49, Black, a married mother of six who lived a short walk from the alley behind H Street where she was found dead on that rainy October day. She had been beaten and sodomized with a pipe-like object. It tore through her intestines and abdomen, according to medical examiners. Her ribs were broken. Fuller weighed less than 100 pounds. She had been robbed of $50 and some jewelry.

Years later, her son David Fuller would remember her as “a loving, caring parent.” His mother, he told The Washington Post in 2017, “was the type of person who would go out of her way to do anything for you.”

The pressure on police and politicians to find the culprit — or culprits — was intense. The most promising information came the first day, when a street vendor who found the body told police he saw two men acting suspiciously in the alley, one with an object under his coat. They ran when police first approached the scene.

But there was little else to go by. Then a couple of anonymous phone tips. A caller referenced the “8th and H Crew” and mentioned a few names.

Three days after the murder, detectives, acting on the tip, picked up Yarborough. Then 16, Yarborough was a special-educationstudent at Eastern High School. His IQ was below 70, and he had difficulty reading. He was interrogated for hours without a lawyer or a parent present.

Yarborough said he told police he didn’t know anything about the crime, but he eventually signed a statement that provided some details and names. He would later say he signed the document because he was scared.

Despite the early leads, the investigation stalled. It was not until late November that a 16-year-old girl gave police the name of Calvin Alston, a person she said had talked about committing the crime. The girl later acknowledged being high on PCP when she was interviewed by police. Alston denied being involved but eventually gave police information about Fuller’s death and a few names, including Yarborough’s. Later Alston would testify that police threatened him with life in prison if he didn’t admit to a role in the murder.

The detectives brought Yarborough back in.

According to Yarborough, the questioning this time was relentless. He said detectives slammed him against a desk, injuring his knee, and held his head above a flushing toilet. The detectives denied those allegations under oath and said the injury was preexisting.

Eventually, Yarborough said, the detectives wore him down. He said they read a statement to him given by Alston and told him to corroborate it. Yarborough agreed, and his statement was videotaped.

“The homicide people interrogated me to a point where I wanted to do anything to get out and go home,” Yarborough said, sitting at a Starbucks across from a Whole Foods on a revitalized H Street that bears little resemblance to the neighborhood in which he grew up. “First they had to calm me down from crying.”

His attorneys would later argue that Yarborough’s testimony was coerced. The two lead detectives and a police officer who worked on the case either declined or did not respond to interview requests for this story.

Yarborough’s statement became crucial evidence that helped lead to the arrests and conviction of his fellow defendants and cemented the idea in the public mind that the crime was the work of a ruthless gang, the “8th and H Crew.” All of those charged, however, said there was no gang. Some of them didn’t even know one another.

Ultimately, 10 people were brought to trial in 1985 for Fuller’s murder. After deliberating for seven days, the all-Black jury found two defendants not guilty and six guilty. The jury told the court it was “impossible” to reach a unanimous verdict for Christopher Turner and Russell Overton.

The judge ordered the jury to continue deliberating, and two days later, the jury returned with guilty verdicts for both men. It had taken “40 to 50” more votes to reach a unanimous decision, jurors told reporters later.

Christopher Turner, then 20, was stunned. He was so certain he would be found innocent that he had turned down a plea deal that would have required him to serve just two to six years. Taking a plea deal for something he hadn’t done was something he objected to on principle, he said. “People still ask me, do you regret not pleading guilty and going on with your life? And my answer is no, emphatically no, I don’t regret it.”

David Fuller was 16 when his mother was killed. He knew a few of the defendants. Christopher Turner was three years older and helped manage Fuller’s go-go band. Yarborough was the same age and lived around the corner. Yarborough said he used to bring pies his grandmother made over to the Fuller house.

Fuller, who now lives in Missouri, originally agreed to be interviewed for this article but then did not respond to messages. The Post was unable to locate Catherine Fuller’s other children. But David Fuller talked about his mother and the case in 2017 for a Post story.

By then, he said, he had found a measure of peace with what had happened. “Even with loss you got to keep going,” he said.

And he acknowledged that some or all of the men may not have been responsible. “My heart goes out to some of the gentlemen if they were falsely accused, because they suffered,” he said.

Russell Overton, 65, folds his 6-foot-7-inch frame into an armchair in the living room of his 85-year-old mother’s tidy Silver Spring home. He has lived here with his sister since his release in March 2022.

Overton, the last of the men to be released, was the oldest of them when they were arrested. He was 26 then and had children. Now he is a great-grandfather and getting to know his family as a free man.

The adjustment hasn’t been easy. Overton still sleeps with his door open and wakes at every sound. He keeps his toiletries in a container on his dresser the way he did when he was locked up. He has a job at a warehouse where he is doing well but is still coming to terms with engaging in pleasantries and trusting people.

“What happened to [Catherine Fuller] was wrong. I’m sorry that it happened. Sympathy for her family,” he said in an interview, leaning forward in his chair. “But there’s no way I can have remorse when I never did have anything to do with it. I wasn’t no angel out there. I got in trouble here and there, but I didn’t do this.”

The system, he said, failed them all.

In 1995, while still in prison, Christopher Turner wrote to Post reporter Patrice Gaines, who had helped cover the original trial. He told her he wanted her to know he was innocent. Gaines looked into the murder and made discoveries that raised questions.

In 2001, Gaines reported that Harry Bennett, called as a witness in the case, told her he had falsified testimony to avoid a life sentence.Bennett said the prosecutor, Jerry Goren, “painted a picture for me. All I had to do was say yes.”

Gaines would also learn a critical piece of information never turned over to the defense. Three weeks after Fuller’s murder, a woman named Ammie Davis told police she had been in the alley that day shooting heroin and saw a man she knew named James Blue. She said Blue savagely attacked a woman and stole money from her in the alley. The week before the Fuller trial began, Blue fatally shot Davis. He died in prison in 1993.

The defendants in the Fuller case challenged their conviction in D.C. Superior Court in 2012 and learned during discovery that another key piece of information was never turned over.

One of the men who ran when police first approached the scene was James McMillan, a 19-year-old who was new to the neighborhood. Three weeks after Fuller’s body was found, McMillan was arrested in two violent assaults and robberies of middle-aged women in the neighborhood. But even though he had been identified at the scene by three witnesses, prosecutors did not share that information with the defense in the Fuller case.

Eight years after Catherine Fuller’s murder, McMillan would be arrested for the murder and forcible sodomy of a woman in an alley in the same H Street neighborhood. He is serving a life sentence in federal prison in Virginia. He declined through prison officials to be interviewed and previously denied any responsibility for Fuller’s death.

During the 2012 proceedings, Goren, the prosecutor, admitted that evidence had been withheld from the defendants. He testified that he didn’t pass on information about McMillan because he did not believe it relevant enough. He also said he didn’t tell the defense about Davis because he didn’t find her story credible.

Reached briefly by phone at his California home earlier this year, Goren declined an interview.

D.C. Superior Court Judge Frederick H. Weisberg ultimately rejected the bid for a new trial, saying the “petitioners have not come close to demonstrating actual innocence.” In 2015, the D.C. Court of Appeals confirmed that ruling. The Supreme Court decision in 2017 ended any hopes the men had of having their convictions overturned.

For some who have followed the case, the Supreme Court ruling was the culmination of a process that has been flawed at every step of the way.

“It’s reaffirmed for me that there are some deep systemic problems in the legal system and that those need to be fundamentally changed,” said Thomas L. Dybdahl, whose book, “When Innocence is Not Enough: Hidden Evidence and the Failed Promise of the Brady Rule,” tracks the legal journey of the Fuller murder defendants in the context of examining Brady disclosure requirements.

Dybdahl argues that even though the Brady rule requires prosecutors to hand over favorable evidence to the defense, they have little incentive to do so because they face little threat of punishment for not adhering to it.

The defendants in the Fuller case “didn’t want mercy, they wanted justice,” Dybdahl said. “Unfortunately, they didn’t get either.”

In 1985, Michele Roberts was a D.C. public defender representing Alphonso Harris, one of the men charged in Fuller’s murder. Roberts, who retired last year as the executive director of the NBA Players Association, remembers the “intense pressure on the government” to get a conviction. Her client was one of the two defendants to be found not guilty.

While her client went free, Roberts said the evidence withheld from the defendants would have been critical to the outcome of the case.

“If I had what we later discovered … all of them would have walked,” she said. “The most powerful evidence that you can present as a defense attorney, if it’s credible, is to be able to say ‘Not only did my guy not do it, but let me tell you who did.’”

John Williams, a lawyer with the powerhouse Washington firm Williams & Connolly who represents Yarborough and argued the men’s case at the Supreme Court, said one option may be available to the defendants to provide them some measure of justice.

Williams said he and the other attorneys are actively considering petitioning for a presidential pardon. It is a complicated process that could take years, and there is no guarantee they will be successful.

“Those are always long shots,” he said. “But these men are incredibly deserving.”

“They were wrongly labeled as murderers. The system still regards them as murderers,” Williams said. “I understand why they’re continuing to fight, and that’s why we are continuing to fight for them.”

In late October, the six surviving defendants wore suits to the funeral of their gregarious and fun-loving fellow defendant Kelvin Smith, known to all of them by his nickname, ‘Hollywood.’ On a breezy, sunny afternoon at a cemetery in Hyattsville, they walked past rows of headstones and markers to the gravesite. One of Smith’s favorite songs, “Bitter Sweet Symphony” by the Verve, played through a speaker nearby.

Smith was Christopher Turner’s best friend. On the day of the funeral, Turner said he thought about how little freedom his friend had been able to enjoy and how he wouldn’t live to see his name cleared. “I felt bad because I wanted him to have that moment,” Turner said.

On days when he struggles to find the energy for this fight, Turner said, he thinks about Hollywood and about Steven Webb, who died in prison. And he thinks about his fellow defendants and their families and friends, whose lives were forever changed by a horrific crime in a small garage in an alley in Washington almost 40 years ago.

“I’m not even sure what keeps me going,” he said. “I just know there’s a fire burning inside me to right a wrong.”

#DC#Wrongfully Imprisoned#Fake Evidence#No Rape#They served decades in prison for a crime they say they didn’t commit#Black Lives Matter#Six men#wrongly convicted of a rape/murder in 1984#with no recourse with no DNA evidence available

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

the mc of the book im reading is convinced that a man could not possibly be a bad guy bc his "...strong bone structure was too clean-cut for someone prone to deviant behavior." completely disregarding the fact that he is a prisoner. in a prison.

#what kinda [im ashamed i cant remember the word. using facial traits to determine character.] bs is she on???#also im sure itll be revealed in the coming chapters that 'ohhhh hes NOT a bad guy! he was wrongfully convicted!'#but like her reasoning. bonkers.#also my dude is apparently a full on alien but his name is Simon#smh

3 notes

·

View notes