Text

8th Stop: Everything on the Internet are Networked, Even Hating Women

Networked hatred and harassment

Harassment has been defined as:

Being called offensive names, being embarrassed online, being physically threatened online, being sexually harassed online, being harassed over a long time, being hurt online by a romantic partner, being impersonated, spreading damaging rumors online, encouraging others to harass you online, and attempting to hurt the victim in person after online harassment (Lenhart et al., 2016)

According to this definition, harassment encompasses a wide spectrum, ranging from minor incidents like name-calling to severe forms of abuse. Nonetheless, pinpointing the exact boundaries of harassment is challenging due to its multifaceted and evolving nature. Ongoing debates persist regarding the interpretation of sexual harassment, with its definition being heavily influenced by contextual factors. As a result, there is often a lack of consensus on what constitutes sexual harassment, as perceptions of it can vary greatly among individuals (Fairchild 2010, p.194). Furthermore, sexual harassment is both a manifestation of and a contributor to gender inequality, adding layers of complexity to its identification. Determining where acceptable behavior ends and harassment begins is not always straightforward, as power dynamics and definitions are intricately intertwined.

Regardless of the specific definition of harassment, research indicates that women, particularly those from marginalized communities such as women of color and queer women, face heightened vulnerability to online harassment. Negative behaviors are more likely to be perceived as harassment by women, to the extent that some young women consider it a normative aspect of their online interactions (Lenhart et al. 2016; Vitak et al. 2017). This trend extends to women occupying public roles, such as journalists and politicians, who commonly experience online harassment (Barton & Storm 2014; Krook 2017). Consequently, harassment serves as a means to regulate women's online conduct and may deter their active engagement in both online and offline public spheres.

Scholars in feminist studies have coined various terms like "online hate," "e-bile," "gender trolling," and "online misogyny" to illuminate how online behaviors perpetuate structural sexism and violence against women (Banet-Weiser & Miltner 2016; Citron 2014; Fairbairn 2015; Franks 2012; Jane 2014; Mantilla 2013). Regardless of the specific targets or circumstances, much of the harassment directed at women online centers around their gender, manifesting in forms such as sexist language, pornographic content, and threats of sexual violence. Banet-Weiser and Miltner introduced the term "networked misogyny" to underscore the coordinated and organized nature of such behavior, highlighting its systemic and pervasive nature.

“We don’t usually think of online harassment as a social activity, but we do know from the strategies and tactics that they used that they were not working alone, that they were actually loosely coordinating with one another. The social component is a powerful motivating factor that works to provide incentives for perpetrators to participate and to actually escalate the attacks by earning the praise and approval of their peers” - Sarkeesian, in a passionate talk at TedWomen, explained how the “cyber mob” targeting her worked in a gamified context.

This networked misogyny frequently finds organization within subcultural online hubs like Reddit, 4Chan, and chat rooms, where participants collaboratively portray feminists like Sarkeesian as antagonists or "villains." In these spaces, such depictions serve to rationalize and justify the harassing conduct, often granting those involved a sense of moral superiority (Jhaver, Chan, & Bruckman 2018).

Where does this point of view come from, and how is it perpetrated online?

The Manosphere: A Collection of Lonely Modern Men

The Men’s Rights Movement (MRM) traces its origins back to the early 1970s when college-age men engaged with the emerging Women’s Liberation movement (Fox 2004; Messner 1998). Initially, scholars within this movement, such as Warren Farrell, Marc Fasteau, and Jack Nichols, acknowledged the harm caused by sexism towards women but also highlighted the negative impact of strict gender roles and patriarchal society on men (Coston & Kimmel 2012). Early literature from the "Men’s Liberation" era addressed issues like emotional stoicism, unequal child support obligations, male-only draft requirements, and the societal pressures of traditional male masculinity (Shire 2013).

However, a faction within the Men’s Rights Movement, known as Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs), veered away from these original ideals. They contended that white men in America were facing a crisis, attributing the perceived decline of American culture to feminism and liberalism (Bean 2007). This perspective emerged amidst significant geopolitical and socioeconomic changes of the 1980s, marked by events like Reaganomics in the US and Thatcherism in the UK, which led to social upheaval (Faludi 1991; Kennedy 1996). The contemporary men’s rights movement reflects a reaction to the diminishing social status of cisgender white men and the rise of feminist and multicultural activism, positioning itself in opposition to feminism while ostensibly advocating for men’s rights (Allan 2016).

The manosphere encompasses various groups, including Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs), pickup artists, Men Going Their Own Way (MGOW), incels (involuntary celibates), father’s rights activists, and others. Despite their diversity, these groups share a central belief that society is dominated by feminine values, which they perceive as suppressed by feminists and "political correctness." They argue that men must resist what they see as an overreaching, misandrist culture to safeguard their existence (Marwick & Lewis 2017).

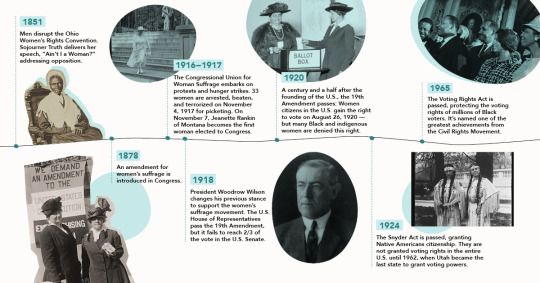

In the context of the #MeToo movement, opinions diverge widely. While some view #MeToo as a significant stride for feminism, likening it to a rewriting of history and a pivotal moment for gender equality akin to women gaining the right to vote, others criticize it as an unjustified vilification, character assassination, and witch-hunt against men. They fear that #MeToo risks demonizing all men and undermining their legal rights.

However, despite the contentious perspectives on women presented within the manosphere, it also provides explanations for and proposed solutions to real challenges faced by young men. Data reveals alarming trends such as men falling behind in education engagement and outcomes, along with a notable rise in young male economic inactivity over the past two decades (Rich & Bujalka 2023).

The manosphere resonates with its audience because it addresses the tangible struggles experienced by young men, including romantic rejection, alienation, economic hardship, loneliness, and a doom outlook on the future. These shared experiences unify them and propel them towards the shared goal of undermining feminism.

How Can You Be a Better Man?

Although digital misogyny is networked, it originates from individuals' deeply ingrained anxieties and fears, which tend to spread to others. Therefore, what steps can we take to improve the situation?

Encourage discussions and initiatives that promote healthy expressions of masculinity

Offer community support

Promote education on gender equality and empathy-building programs

Increase access to mental health services and destigmatize seeking help for mental health issues among men

Encourage critical engagement with ideologies propagated within the manosphere

Reference

Allan, JA 2015, ‘Phallic Affect, or Why Men’s Rights Activists Have Feelings’, Men and Masculinities, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 22–41.

Banet-Weiser, S & Miltner, KM 2015, ‘#MasculinitySoFragile: culture, structure, and networked misogyny’, Feminist Media Studies, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 171–174.

Barton, A & Storm, H 2014, Violence and Harassment against Women in the News Media: a Global Picture - IWMF, www.iwmf.org, International Women’s Media Foundation, DC.

Bean, K 2007, Post-Backlash Feminism, McFarland, North Carolina.

Coston, B & Kimmel, M 2013, ‘White Men as the New Victims: Reverse Discrimination Cases and the Men’s Rights Movement’, Nevada Law Journal, vol. 13, no. 2, viewed 10 April 2024, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/White-Men-as-the-New-Victims%3A-Reverse-Cases-and-the-Coston-Kimmel/a3039c71bcf6c2573d5dd8066f3e3973c1eb9454.

Danielle Keats Citron 2016, Hate Crimes in Cyberspace, Harvard University Press, MA. Fairbairn, J 2015, ‘Rape Threats and Revenge Porn: Defining Sexual Violence in the Digital Age’, in VM Steeves & J Bailey (eds), EGirls, ECitizens, University Of Ottawa Press, Ottawa, Ontario.

Fairchild, K 2010, ‘Context Effects on Women’s Perceptions of Stranger Harassment’, Sexuality & Culture, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 191–216.

Faludi, S 1991, Backlash: the Undeclared War against American Women, Three Rivers Press, New York.

Fox, J 2004, ‘How Men’s Movement Participants View Each Other’, The Journal of Men’s Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 103–118.

Franks, MA 2009, Sexual Harassment 2.0, Ssrn.com, viewed 10 April 2024, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1492433.

Jane, EA 2012, ‘“Your a Ugly, Whorish, Slut”’, Feminist Media Studies, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 531–546.

Jhaver, S, Chan, L & Bruckman, A 2018, ‘The view from the other side: The border between controversial speech and harassment on Kotaku in Action’, First Monday.

Kennedy, L 1996, ‘Alien Nation: White Male Paranoia and Imperial Culture in the United States’, Journal of American Studies, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 87–100.

Krook, ML 2017, ‘Violence Against Women in Politics’, Journal of Democracy, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 74–88.

Lenhart, A, Ybarra, ML, Zickuhr, K & Price-Feeney, M 2016, Online Harassment, Digital Abuse, and Cyberstalking in America, Data & Society Research Institute, New York.

Lewis, B & Marwick, AE 2017, Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online, Data & Society.

Mantilla, K 2013, ‘Gendertrolling: Misogyny Adapts to New Media’, Feminist Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 563–570.

MESSNER, MA 1998, ‘The Limits of “The Male Sex Role”’, Gender & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 255–276.

Rich, B & Bujalka, E 2023, The draw of the ‘manosphere’: understanding Andrew Tate’s appeal to lost men, The Conversation.

Shire, E 2013, A short guide to the Men’s Rights Movement, theweek.com.

Vitak, J, Chadha, K, Steiner, L & Ashktorab, Z 2017, ‘Identifying Women’s Experiences With and Strategies for Mitigating Negative Effects of Online Harassment’, in Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, OR: ACM, Portland.

0 notes

Text

7th Stop: You Have to Learn in Genshin Impact, and It's Not Exactly Easy

If you've played Genshin Impact, you're likely familiar with the struggle every newbie encounters. The mantra “Teyvat has its own laws” demands both gaming prowess and extensive exploration. With 9 cultural maps, seven types of quests, five "gacha" banners, 82 playable characters each with unique abilities, 243 enemies scattered throughout the open world, numerous weapons, tools, and puzzles, as well as an intricate, overlapping storyline, the game presents a vast and complete fictional world. The game even has its own languages. Even after playing for a year or two, many players still feel like newcomers in the Genshin Impact community due to the sheer volume of knowledge required to navigate the game.

In response to this complexity, players have created knowledge communities—a space where they can ask questions, share information, and discuss strategies tailored to their needs. These communities consist of smaller groups that players move between based on skill, expertise, and knowledge. In contrast to traditional media like films or books with finite plots, games like Genshin Impact offer an ever-expanding world, with new content released regularly. As players progress through the game, they continually encounter new challenges and questions, ensuring that the need for knowledge sharing and discussion remains constant, a part of their journey and life as a citizen of Teyvat.

We share knowledge, although people call us brainrot for playing Genshin Impact

“The new knowledge communities will be voluntary, temporary, and tactical affiliations, defined through common intellectual enterprises and emotional investments.” Jenkins (2006, p.136)

Members seamlessly transition between different communities based on their evolving interests and needs, often participating in multiple communities simultaneously. Within Genshin Impact communities, players congregate in various subchannels on platforms like Discord, each dedicated to different aspects of the game, such as screenshotting in-game scenarios, character building, quest guidelines, achievements, and "gacha" tips and tricks. Despite these diverse interests, they remain united by their shared commitment to producing and exchanging knowledge.

Online fan communities reflect Lévy's (1997) concept of cosmopedia, functioning as self-organizing groups focused on collectively interpreting and discussing various aspects of popular culture artifacts. These communities transcend geographical boundaries, uniting members based on shared interests rather than physical proximity.

Nancy Baym (1998) has discussed the important functions of talk within digital communities, or in this case, players with mutual interest in Genshin Impact. They share knowledge of the game's history because the genre demands it. 'Any game has released more material than any single player can remember.' Players inform each other about past events or recent developments they may have missed. The game community pools its knowledge because no single fan can know everything necessary to fully appreciate Genshin Impact. Lévy (1997) distinguishes between shared knowledge (which would refer to information known by all members of a community) and collective intelligence (which describes knowledge available to all members of a community). Collective intelligence expands a community's productive capacity because it frees individual members from the limitations of their memory and enables the group to act upon a broader range of expertise. As Lévy (1997) writes, within a knowledge community, 'no one knows everything, everyone knows something, all knowledge resides in humanity.’

Beyond What Mihoyo Officially Created

Baym's (1998) concept of 'socioemotional' emphasizes that meanings within fandoms are not purely intellectual; they are intertwined with emotions and desires, shaping the bonds that hold communities together. In the Genshin Impact community, shared expressions of emotion and desire, often referred to as 'drool' by fans (Clerc 1996), play a significant role alongside the exchange of game-related information. Yet, at the same time, conflicting assumptions and interpretations, competing ways of knowing can become the basis for deeply felt antagonisms, with 'unforgivable' lapses resulting in social rifts. Players’ speculations may, on the surface, seem to be simply a deciphering of the aired material, but increasingly, speculation involves fans in the production of new fantasies, broadening the field of meanings that circulate around the primary text.

In Genshin Impact, speculation among players often focuses on the game's storyline and combat mechanics. Seasoned players, in addition to sharing their knowledge and collaborating with newcomers, actively develop theories aimed at unraveling the mysteries surrounding the main characters' origins and predicting future plot revelations. Each member of the community analyzes the evidence presented in the series, proposing various narratives and alternative scenarios about the protagonists, Lumine and Aether, and the eventual outcome of the story. It is doubtful whether the solutions ultimately provided by the series will match the complexity and originality of the theories generated by the players.

Moreover, players have surpassed the expectations set by the game developers, particularly in terms of combat mechanics. Many players find that the trial versions of characters provided by the game are too weak compared to the powerful builds they have created for their characters. Just when it seems that a character's abilities have reached their peak, players discover new combinations of teams, weapons, and artifacts that elevate their effectiveness even further.

Levy contrasts his ideal of 'collective intelligence' with the dystopian image of the 'hive mind,' where individual voices are suppressed. Unlike the stifling conformity associated with a hive mind, this new culture celebrates diverse ways of knowing and encourages the free exchange of ideas. This collective exchange of knowledge cannot be fully contained by previous sources of power: 'bureaucratic hierarchies' (based on static forms of writing), media monarchies (surfing the television and media systems), and international economic networks (based on real-time technologies), which depended on maintaining tight control over the flow of information.

In the evolving information landscape, various forms of recontextualization emerge, often unstable yet rich with potential. The significance of information grows through social interaction, emphasizing the role of collective engagement in shaping its value. While commodities are finite and their exchange can perpetuate inequalities, meaning stands apart as a communal and ever-renewable resource. As it circulates, meaning has the power to forge and rejuvenate social connections, underscoring its transformative capacity within communities.

Reference

Baym, NK 1998, ‘Talking about Soaps: Communication Practices in a Computer-Mediated an Culture’, in C Harris & A Alexander (eds), Theorizing Fandom: Fans, Subculture, and Identity, vol. 42, Hampton Press, New York, no. 1_suppl, pp. 29–52.

Clerc, S 1996, ‘DDEB, GATB, MPPB and Ratboy: The X-Files Media Fandom Online and Off’, in D Lavery, A Hague & M Cartwright (eds), Deny All Knowledge: Reading the X-Files, Syracuse University Press, New York.

Jenkins, H 2006, ‘Interactive Audiences? The “Collective Intelligence” of Media Fans’, in Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture, New York University Press, New York, pp. 134–151.

Lévy, P 1997, Collective Intelligence: Mankind’s Emerging World in Cyberspace, Cambridge, Mass Perseus Books.

0 notes

Text

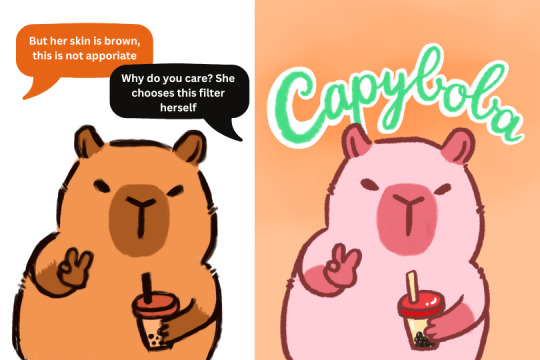

6th Stop: The Online Body and The Authentic Self

Many of us have our go-to filters, which serve as digital mirrors reflecting our online lives. As someone who habitually embellishes my photos with filters, I contend that these tools, akin to traditional photo editing, vintage cameras, and carefully staged compositions, offer us the means to craft a visually pleasing narrative of our reality, which also holds authenticity in them.

Defamiliarizing Life Online: La Vie En Rose

The use of photo filters not only enhances the visual appeal of our images but also, as Sontag refers to the portrayal of war imagery, can desensitize us to the mundane aspects of our daily lives (1973, 20). Yet, concurrently, filters present us with images that deviate from the familiar scenes we're accustomed to witnessing.

One reason why filters captivate us is their ability to give images a sense of strangeness, defamiliarizing our everyday existence. Filters steal a little bit of our images; they corporate our vision with what the lens of a machine portrays.

Let me see my life through someone else’s eyes—or, in this case, the unfocused and impartial eye of a machine - Bianca Bosker (2014)

Although Instagram-style filters may initially render our selfies and everyday snapshots unrecognizable, their widespread usage eventually diminishes the effect of defamiliarization, transforming it into a commonplace occurrence. Nevertheless, our everyday photos serve as a means of heightening our personal experiences and giving them special meanings.

In essence, these filtered photos afford ordinary individuals the opportunity to engage in artistic expression—a realm once reserved for professionals due to the intricacies of photography and editing tools such as DSLR cameras and Photoshop. And each photo serves as a narrative that we consciously choose to share.

Platformatization: Finding Authenticity in Filters

Behavior of any kind, even that wholly in accord with societal mores, is authentic if it results from personal understanding and approval of its drives and origins rather than merely from conformity with the received wisdom of society. - Erich Fromm (2011)

Behavior, whether conforming to societal norms or not, is considered authentic by Erich Fromm (2011) if it stems from an individual's personal understanding and endorsement of its underlying motivations and origins, rather than mere conformity to prevailing societal expectations. Fromm views authenticity as a positive result of informed and enlightened motivation, rather than a negative consequence of rejecting societal pressures.

For instance, when selecting a filter for a photo, individuals make subjective choices that reflect their authenticity (Kumar & Madhushree Nanda Agarwal 2023). Consider a woman of color opting for a filter adhering to Western beauty standards. Her choice may signify a desire for societal acceptance, despite the inherent social injustices minorities face. In this context, her selection of a filter becomes a statement about her own experiences and struggles.

Platformization has transformed filters into customizable tools, allowing greater freedom to shape representations that reflect the diversity of our world. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook empower users, predominantly individuals, to design their own filters tailored to their unique needs and authenticity. Today, filter development is just as, if not more, likely to be conducted by a camgirl as it is by hundreds of full-time employees in a campus-sized studio. Skill-based barriers to entry have been eroded by the proliferation of low-cost and easy-to-use software development platforms known as AR toolkits .

These toolkits prioritize the creator's vision over technical expertise, resulting in a diverse range of filters that challenge conventional beauty standards. These filters may explore themes of disempowerment rather than conquest or feature mechanics that promote introspection over agency, thereby expanding the narrative possibilities and contributing to a more inclusive representation of reality.

Indeed, the filtered world we create online may diverge from its natural state, but it remains authentic in its own right. Through the lens of a digital camera, we craft a human-made vision of reality that reflects our perceptions, experiences, and desires. While this digital representation may not mirror the raw world, it nonetheless captures aspects of our inner selves and external surroundings, rendering it authentic in its portrayal of our lived experiences. Our online reality, shaped by filters and digital tools, serves as a unique and valid expression of our individual perspectives and narratives.

Reference

Bosker, B 2014, Hi, My Name Is Bianca And I’ve Already Taken Your Picture, HuffPost, viewed 31 March 2024, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/narrative-clip_n_4760580.

Fromm, E 2011, Escape from freedom, Ishi Press, New York, Tokyo.

Kumar, H & Madhushree Nanda Agarwal 2023, ‘Filtering the reality: Exploring the dark and bright sides of augmented reality–based filters on social media’, Australian Journal of Management, SAGE Publishing.

Rettberg, JW 2014, ‘Filtered Reality’, in Seeing Ourselves Through Technology: How We Use Selfies, Blogs and Wearable Devices to See and Shape Ourselves, Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 20–32, viewed 31 March 2024, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661_2.

Sontag, S 1978, On Photography, Allen Lane, London.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

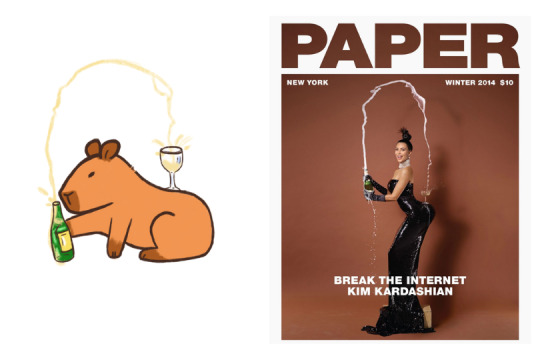

5th Stop: Is Kim K Slave to Her Own Body or Vice Versa?

The secret to the Kardashian empire is that they maintain the perfect balance on the fine line between two sides of every problem that they have created. Pro-feminist or anti-feminist, sexual liberation or pornification, in control or objectified? Kim K is not any woman; she is at the frontier of these controversies and is clever enough to stay in-between space or flux between the bound and unbound, which finally breaks the binaries and creates new feminine identities for the contemporary workers of glamour labour.

She is wearing her body, and you will follow her

In the new era of post-fashion, ‘[e]ffortless is no longer the goal – now, a body has to look like the product of work’, the kind of work evidenced by Kim Kardashian’s effortful body,” Hyland (2015).

This is a departure from the role of glamour in the past, where the point was to hide the work, and to make it look like it was natural and effortless.

By revealing her effort, Kim shows us how she is the all-American girl with an all-American work ethic, and if we just work hard too, we will make it like she did. Her overarching message is that you gotta work it, so you can be like me! Play my game, and you will be training yourself for the life of glamour: Practice here, and if you play the game right in real life, you can achieve the dream of fabulous wealth, fame, and an enviable lifestyle. How do you get all of this? Photoshop, filters, cosmetic surgeries, heavy editing, personal trainers, makeup, cucumber salad, skincare, poses, and designed clothes—all of which are the labours that we sacrifice without thinking to be just an ounce like the Amerian billionare family.

Kim’s attitude exudes the idea that we are just girlfriends hanging out, just let her show you: ‘Here is how you do make-up like mine’. Her feed is populated by photos and videos of her sharing instructions about how to get her look, achieve a body like hers, and dress it as she does. The tone is friendly, instructional, encouraging, and luring. By now, Kim’s make-up tutorials have become quite well known, so notorious in fact that they make it onto several 'make-up trends to leave behind’ every year.

To attain similar success, the consumption of specific fashion and beauty products is needed. Kim’s minions do not know exactly why Kim is on such a high social ladder; whether it is because of her provocative appearance, acts of female liberation and empowerment, or sex-positive attitudes, they just replicate her as much as they can to become like her. And slowly, they learn to hate their bodies, because it is only when they cannot stand their looks that they become loyal consumers of the ever-expanding beauty industry.

An Empire Built on Glamour

‘Glamour labour’ is the work to edit the self and body so that one appears to be the highly scripted, filtered, and carefully constructed image, which so many work so hard to create and present online (Wissinger 2015).

In 2012, communication scholar Gina Neff described the ‘give it all to have it all’ imperative of highly uncertain ‘venture labor.’ Recent scholarship has documented how this imperative has spread via social media technologies, whose promises of easy success lure many to work hard at putting themselves out there. Media studies scholar Alice Marwick (2013) noticed this trend in the promotional labour needed to achieve high online status. Similarly, communication scholar Sarah BanetWeiser (2012) tracked the spreading imperative to build one’s online brand, with women and girls feeling these pressures most keenly. As communication professor Brooke Duffy’s (2015) study of fashion bloggers shows, the ‘romance of work’ plays on worker’s aspirations to achieve the good life, where work is play and play is work, and good things come to only a few of the many who mercilessly perform their lives to supply their endlessly voracious Instagram feed.

As these studies show, in the digitized world, many are willing to give up much for glamorous work. Forget job stability, health insurance, or even pay! If you can be on the inside of the media machine, you are one step closer to the glittery riches it promises to all, yet rewards to very few. The game is rigged, yet, in a neo-liberal world, failure is always your fault. If you experience society as racist, classist, or sexist, it is only because you are not working hard enough. It is up to you to fix your life, to build your brand, and to become the kind of famous person who reeks of success.

Over-sharing, a Kardashian specialty, takes on a glamorous sheen, when coupled with the trappings of the celebrity lifestyle that the family has achieved by seeming to do nothing.

The Kardashians’ joyful abdication of the right to any privacy at all, paves the way towards normalizing the loss of privacy rights, drawing us into the world where the ‘“likes”, clicks, and tweets that can be earned by sharing’ seduce us into what legal scholar Bernard Harcourt (2015) has called a 'mad frenzy of disclosure’ (pp.18) as we buy into the discourse of ‘datafication’ (pp. 21). Self-tracking taps into the voracious desire for self-improvement, providing new fodder for the ongoing practices of online self-documentation, as we post our step scores, tweet our opinions, Facebook our vacation, and Instragram pictures of our dinner plates. Insidiously, our loss of privacy is what the Kardashians hide in plain sight.

Glamour labouring to chase an ever-receding ideal of looking right, feeling right or being in the right circle, where the desire for pleasure trumps the need for privacy, leaves us as routinely exposed as Kim Kardashian’s backside. Perhaps, it's not Kim who is enslaved by her body, but rather, it is us who workship, resent, and invest so much in ours.

Reference list

Alice Emily Marwick 2013, Status Update: celebrity, publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Banet-Weiser, S 2012, AuthenticTM the politics of ambivalence in a brand culture, New York, N.Y. New York University Press.

Duffy, BE 2016, ‘The Romance of Work: Gender and Aspirational Labour in the Digital Culture Industries’, International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 441–457.

Harcourt, BE 2015, Exposed: Desire and Disobedience in the Digital Age, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Hyland, V 5AD, What the Rise of the Couture Body Means for Fashion, The Cut, viewed 10 November 2021, https://www.thecut.com/2015/05/rise-of-the-couture-body.html.

Neff, G 2015, Venture labor: Work and the Burden of Risk in Innovative industries., Mit Press, Cambridge.

Stevenson, T 2019, ‘The Kardashian complex: Performing Sexuality and Femininity through Image and Screens’, Scope: Contemporary Research Subjects (Art & Design 17).

Wissinger, E 2015, This year’s model : fashion, media, and the making of glamour, New York University Press, New York.

0 notes

Text

4th Stop: Greenwashing as a Rapid Escape from Authentic Slow Fashion

Being Slow is the New Sexy

Informed consumers are increasingly prioritizing the long-term well-being of both people and the planet, leading to the emergence of the Slow Fashion movement (Fletcher 2010; Freudenreich & Schaltegger 2020). This movement advocates for a shift towards sustainable practices and a reevaluation of core values within the fashion industry (Şener, Bişkin & Kılınç 2019; Clark 2008), emphasizing the production of durable products using traditional techniques that transcend seasonal trends (Jung & Jin 2016a, 2016b).

Slow Fashion encourages brands to adopt a business philosophy centered on quality rather than speed, promoting slower production methods, ethical practices, and the creation of well-designed, long-lasting products. Consumers are drawn to sustainable consumption by the prospect of minimizing environmental harm without compromising on style, viewing sustainability as a means to enhance both personal satisfaction and well-being (Bly, Gwozdz & Reisch 2015, p. 12).

Existing literature highlights a set of values identified by Şener, Bişkin, and Kılınç (2019), as well as Štefko and Steffek (2018), which play a significant role in driving sustainable consumption. These values, combined with individual ethics, include authenticity, locality, exclusivity, equity, and functionality.

On the other hand, when considering the quality, price, aesthetics, and availability of sustainable fashion, most customers view them as trade-offs that they are not willing to pay for the vague faraway ecological benefits. Ironically, slow fashion, while expected to be the opposite of the pro-trend throwaway attitude of fast fashion, seems to be perceived as a short-term trend that most consumers and businesses do not deem serious (Lai, Henninger & Alevizou 2017).

Green Washing to the Rescue

“Disinformation disseminated by an organization so as to present an environmentally responsible public image; a public image of environmental responsibility promulgated by or for an organization, etc., but perceived as being unfounded or intentionally misleading” - Concise Oxford English Dictionary

The fashion industry is rife with vague buzzwords, narrowly focused goals, cherry-picked objectives, and unsupported green claims. For instance, the 'Halo effect' or tokenism makes it challenging for consumers to distinguish between a company's overall image and the actual sustainability of its products (Lyon & Montgomery 2015). H&M's introduction of the Conscious collection in 2010, which initially touted sustainable practices, has faced criticism for creating a sustainable collection that merely serves as a passing trend rather than encouraging consumers to prolong the lifespan of their existing clothes (Mondalek, 2020). Moreover, they are also under attack, on the one hand, over having a specific collection that is sustainable while, on the other hand, having most of the product range as ordinary fast fashion products that are not sustainable (Mondalek, 2020).

Another aspect of greenwashing involves selective disclosure, where companies highlight positive information while concealing negative aspects (Lyon & Montgomery 2015). For example, H&M promoted its recycling program in the Close the Loop ad, while it was revealed in 2017 that the company sourced viscose from factories in China and Indonesia causing environmental pollution (Hoskins 2017). Additionally, H&M's self-reported Higg Index scores only provide average environmental impact data for types of textiles, rather than the complete impact of manufacturing and selling a specific clothing item (Ponte 2023). This demonstrates how companies use green communication tactics to mislead consumers and associate themselves solely with positive attributes.

Other greenwashing tactics includes:

False or Exaggerated Claims

Green Marketing Gimmicks

Misleading Labels and Certifications

Limited Scope

Incomplete or Inaccurate Information

“But I cannot afford sustainability…”

Park and Pellow (2011) argue that when there is environmental injustice, there must also be environmental privilege, which they describe as resulting from "the exercise of economic, political, and cultural power that some groups enjoy, which enables them exclusive access to coveted environmental amenities."

Using clever marketing and advertisements, the fashion industry echoes this theme, where consumers are able to maintain their consumption habits while simultaneously convincing themselves they are doing something good for the environment by buying "eco-friendly" or "sustainable" fashion.

Kari Norgaard's (2012) fieldwork in Norway found that it is not in fact true that people are unconcerned with the reality of climate change; rather, their awareness and concern make them so uncomfortable that they end up pushing it away and dealing with more manageable everyday life issues instead.

According to Leon Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance (1957), in order to resolve this inconsistency, one of the cognitions needs to be changed (Norgaard 2012). Norgaard argues that if people feel a sense of guilt or responsibility, they use avoidance and denial as a strategy to escape from that cognitive dissonance (2011, 2012).

It could be that consumers feel concerned about the state of the fashion industry and the pollution it causes, but it's an uncomfortable fact to deal with. It is thus easier to purchase something that is said to be good for the environment or be more eco-friendly with the clothes you own, as these tasks are all manageable within the realms of everyday life. Companies push us in this direction so that we continue to uphold the status quo while feeling like "at least we are trying."

Reference

Bly, S, Gwozdz, W & Reisch, LA 2015, ‘Exit from the high street: an exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers’, International Journal of Consumer Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 125–135.

Clark, H 2008, ‘SLOW + FASHION—an Oxymoron—or a Promise for the Future …?’, Fashion Theory, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 427–446.

Fletcher, K 2010, ‘Slow Fashion: an Invitation for Systems Change’, Fashion Practice, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 259–265.

Freudenreich, B & Schaltegger, S 2020, ‘Developing sufficiency-oriented offerings for clothing users: Business approaches to support consumption reduction’, Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 247, p. 119589.

Hoskins, T 2017, H&M, Zara and Marks & Spencer linked to polluting viscose factories in Asia, The Guardian, www.theguardian.com.

Jung, S & Jin, B 2016a, ‘From quantity to quality: understanding slow fashion consumers for sustainability and consumer education’, International Journal of Consumer Studies, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 410–421.

― 2016b, ‘Sustainable Development of Slow Fashion Businesses: Customer Value Approach’, Sustainability, vol. 8, no. 6, p. 540.

Lai, Z, Henninger, CE & Alevizou, PJ 2017, ‘An Exploration of Consumers’ Perceptions Towards Sustainable Fashion – A Qualitative Study in the UK’, in C Henninger, P Alevizou, H Goworek & D Ryding (eds), Sustainability in Fashion, Palgrave, pp. 81–101.

Lisa Sun-Hee Park & Pellow, DN 2020, The Slums of Aspen: Immigrants vs. the Environment in America’s Eden, New York University Press.

Lyon, TP & Montgomery, AW 2015, ‘The Means and End of Greenwash’, Organization & Environment, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 223–249.

Norgaard, KM 2012, ‘Climate Denial and the Construction of Innocence: Reproducing Transnational Environmental Privilege in the Face of Climate Change’, Race, Gender & Class, vol. 19, no. 1/2, pp. 80–103.

Ponte, C 2023, The H&M Greenwashing Scandal: Has Business Learned the Lesson?, Impakter, viewed 2 March 2024, https://impakter.com/hm-greenwashing-scandal-has-business-learned-the-lesson/.

Şener, T, Bişkin, F & Kılınç, N 2019, ‘Sustainable dressing: Consumers’ value perceptions towards slow fashion’, Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 28, no. 8.

Štefko, R & Steffek, V 2018, ‘Key Issues in Slow Fashion: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives’, Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 2270.

#WEEK 6#MDA20009#Digital Citizenship Case Study: Social Media Influencers and the Slow Fashion Movement

0 notes

Text

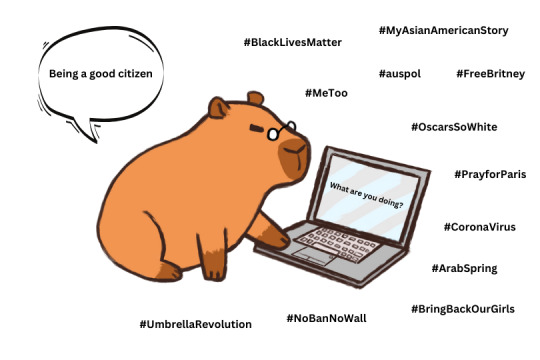

3rd Stop: Moving between Digital Platforms

Digital Citizenship: Understanding People Online

A digital citizen is expected to:

Proficiency in digital technologies

Actively engage in communities across various levels

Participate in a dual process of lifelong learning and continual advocacy for human dignity (Hintz, Dencik, & Wahl-Jorgensen, 2019).

Proficiency in digital platforms is essential for digital citizenship, as differences in technical capabilities among platforms can have diverse political implications. For example, Twitter and Facebook vary in their network structures, methods of information consumption and proliferation, and even user base orientations towards public affairs (Shane-Simpson et al. 2018).

The nature of social connections between Twitter and Facebook significantly influences bridging and bonding social capital and the extent of gender differences in political communication (Koc-Michalska et al. 2021). In comparison with Facebook, Twitter users tend to engage more in political posting, are exposed more frequently to counter-attitudinal political content, and are less likely to receive mobilizing messages or political advertising (Vaccari & Valeriani 2021).

Platformization and Online Political Participation in Action

Political engagement in advanced democracies has undergone a transformation. In recent decades, there has been a decline in membership in many traditional collective action-oriented organizations such as political parties and trade unions. Simultaneously, there has been an increase in citizens’ ad hoc involvement with local communities, environmental and human rights organizations, causes, and online social movements, indicating a shift in their approach to long-term allegiances and membership (Vromen 2016).

Social media offers various affordances for facilitating political acts. Some of these acts are simply faster and easier ways to accomplish traditional forms of participation, like sharing a petition or contacting public officials, while others have no direct analogue in the pre-digital era (Theocharis & van Deth 2018). Examples include publicly following a political figure, posting written comments for other people, commenting on others' posts, and forwarding political news, with or without commentary and social endorsement.

Most citizens now engage in politics in individualized, ad hoc ways rather than as committed members of formal groups. This can encompass offline and online petitioning, monetary donations, ad hoc volunteering, and boycotting or buycotting consumer items over political concerns.

The emergence of social media has introduced a heightened everyday sociality to political interactions online, embedding political engagement within everyday cultural production and consumerism.

The Shifting Nature of Political Involvement

Changes in political engagement signify a departure from traditional modes of engagement towards ‘citizen-initiated’ and ‘policy-oriented engagement’ (Dalton 2019). This shift is reflected in a preference for issue-based campaigns and the ‘politics of the ordinary’, as well as a general inclination towards flexible forms of ‘individualized collective action’ (Bang 2005; Micheletti 2003).

“The politics of choice appears to be replacing the politics of loyalties” (Norris 2002, p. 4).

Citizens are less likely to be passive subjects and more likely to demand a say in the decisions affecting their lives. The new style of citizen politics reflects a more active participation in the democratic process (Dalton, 2008, p. 9).

Digital divide, however, acts as a barrier to the ideal form of public sphere. Subsequent analyses of the digital divide suggest that the issue is no longer about access to the internet but rather political efficacy and the internet’s tendency to simply replicate offline political inequalities.

In other words, individuals who are politically engaged online are typically the same type of people who are active offline. Pippa Norris (2001) acknowledged this early on when discussing a democratic divide where the internet reinforces existing political inequalities rather than mobilizing citizens absent from political engagement and participation.

Reference

Bang, H 2005, ‘Among everyday makers and expert citizens’, in J Newman (ed.), Remaking governance, The Policy Press, Bristol, pp. 159–178.

Cristian Vaccari & Augusto Valeriani 2021, Outside the bubble : social media and political participation in western democracies, Oxford University Press, New York, Ny.

Dalton, RJ 2019, CITIZEN POLITICS - INTERNATIONAL STUDENT EDITION : public opinion and political parties in... advanced industrial democracies., Sage Publications Inc, S.L.

Farkas, J 2020, ‘Hintz, A., Dencik, L., & Wahl-Jørgensen, K. (2019). Digital citizenship in a datafied society. Cambridge: Polity Press, 193 pp.’, Communications, vol. 0, no. 0.

Koc-Michalska, K, Schiffrin, A, Lopez, A, Boulianne, S & Bimber, B 2019, ‘From Online Political Posting to Mansplaining: The Gender Gap and Social Media in Political Discussion’, Social Science Computer Review, vol. 39, no. 2, p. 089443931987025.

Micheletti, M 2003, Political Virtue and Shopping, Palgrave Macmillan US, New York. Norris, P 2013, Democratic phoenix : reinventing political activism, Cambridge University Press, , Cop, Cambridge ; New York.

Shane-Simpson, C, Manago, A, Gaggi, N & Gillespie-Lynch, K 2018, ‘Why do college students prefer Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram? Site affordances, tensions between privacy and self-expression, and implications for social capital’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 86, pp. 276–288.

Theocharis, Y & van Deth, JW 2016, ‘The continuous expansion of citizen participation: a new taxonomy’, European Political Science Review, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 139–163.

Vromen, A 2016, ‘Introduction’, in Digital Citizenship and Political Engagement, Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 1–7.

0 notes

Text

2st Stop: The “RuPaulitics” of TV Drag Culture

Hosted by the established drag artist RuPaul Charles and representing a seismic shift in queer male visibility through the hypervisibility of televised drag performance, RuPaul’s Drag Race 'has served to propel drag culture from the obscurity of the gay bar/club scene to the mainstream of reality television’ (Brennan & Gudelunas 2017).

Much like other reality TV, RuPaul's Drag Race features the complexities of governmentality and the self; nationhood and globalism; gender and sexuality; class and race; and performance.

Drag Culture On-Air: Sissy That Performance!

Paradoxically, performing and competing in drag, framed as a 'race,' creates conflicts within traditional drag norms that celebrate creativity and extraordinariness. This paradox intensifies when large queens are scrutinized and judged based on ideal body image standards, fueling numerous social media wars. In the 'herstory' of Drag Race, no oversized queens have been crowned, despite the ungodly amount of spin-offs within the franchise.

Through a range of increasingly corporate and cross-promotional devices, RPDR has consistently become less about representing drag culture in its diverse communities and more about transforming drag into individuals' advancement and promotion. It has also played a role in shifting common views of drag from a subculture to art and a valid profession.

Starting in 2009, the post-2008 age of austerity, RuPaul’s Drag Race represents one of the most influential shifts in reality TV: 'the neoliberal turn.' The transformative promise of reality TV is grounded in neoliberal values of personal responsibility, entrepreneurialism, and self-empowerment through self-management (Ouellette & Hay 2008). These values are mobilized by experts on 'life intervention' shows to transform 'needy' and underprivileged drag queens into 'functioning citizens' that inspire and contribute to society.

Drawing on a Foucauldian power/knowledge framework, reality television functions as a cultural technology of governmentality, teaching participants, as well as viewers, the knowledge and techniques required for empowerment through self-governance. Each participant, judge, guest, and coach appearing on the show is constructed based on 'the self as project' to function as 'living brands’ (Ouellette 2016). These individualist brands are intricately woven into queer discourses, including gender performativity, street smartness, self-love, homophobia, and other forms of bigotry and oppression, sparking everyday political discussions on social media.

The equation of self-disclosure and self-expression in earlier reality TV has now been conjoined with the demand that neoliberal subjects fashion themselves into branded products to achieve social recognition through accrued attention capital, especially for those caught in the crosshairs of economic precarity and gendered consumption patterns (Andrejevic 2014). Drag queens' participation in the digital economy of self-branding as a form of extracted labor connects with the numerous ways in which neoliberal subjects engage in 'immaterial labor' concentrated as choice and even passion, despite the root in the insecure nature of work for queer people in the US.

Queens competing in RuPaul’s Drag Race remain brand ambassadors long after their initial TV appearances. Their participation in official events like Drag Con (a spin-off convention from the show) and social media promotions, various tours, and public appearances with other queens from the show generate incomes, networks, fame, and endorsements, much more compared to their bar jobs.

Towards the Global Visibility of Rupaul’s Drag Race

Despite its US-centrism, RPDR has made drag queens and drag culture infinitely more accessible to American and global audiences. For American LGBTQ viewers located far from the gay meccas of New York, Chicago, San Francisco, or Los Angeles, and for straight viewers who would not consider attending a drag act, RPDR provides an up-close, even technical view of what drag entails. However, RPDR may be global in distribution, but the question of global values associated with the program is a far more complicated notion.

The international queens on the show are not exactly portrayed in the best light, as RPDR creates and frames divisions between contestants that reveal deep disparities in aesthetics, class, race, and geography (McIntyre & Riggs 2017). Queens who are the intersection of immigrants and urbanists are the outsiders on the show, labeled based on their origin rather than talent ('Latino queens' instead of 'dancing queens' or 'camp queens'), laughed at for their accents, and often criticized for their knowledge gap in US cultures. To the fan community, they are spicy and exotic creatures that contribute to the racial diversity of the show.

Cultural proximity (Straubhaar 1991) affects how global audiences perceive reality TV, especially one with heavy reference to the US drag subculture throughout the history. While due to Brazil’s own long-standing drag/transvesti traditions, Brazilian drag queens, their fans, and followers have made the Brazil version of RPDR their own (Castellano & Heitor Leal Machado 2017), Mexican gay men are skeptical of and resistant to RPDR’s portrayals of drag and queer culture (Villarreal, García & Fernández 2017). Even in Brazil, because homophobia is not only rampant but also institutionalized by politicians and the media, RPDR, while seen as a step up for gay movements, can be divisive to the local gay community. Not all gay people watch RPDR; they may not understand the alienated languages, cultures, and ideologies the program conveys to its fans, which are the values US society holds closest.

Not to mention that in some countries with unfit cultures, infrastructure, and values, they cannot have their own RPDR with nationally imbedded culture, nor can they reasonate with Western-centric jokes. This is contradictory to how Bandura’s (2001) social learning theory is used to explain how RPDR might, possibly, educate audiences, including their levels of empathy for and identification with (Igartua & Muñiz 2008) the show’s contestants. It can be considered a mere hegemonic entertainment show rather than having an actual impact on the local landscapes.

Reference

Andrejevic, M 2014, ‘When Everyone Has Their Own Reality Show’, in A Companion to Reality Television, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 40–56.

Bandura, A 2001, ‘Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication’, Media Psychology, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 265–299.

Brennan, N & Gudelunas, D 2017, ‘Drag Culture, Global Participation and RuPaul’s Drag Race’, in RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Shifting Visibility of Drag Culture, Palgrave Macmillan Cham, pp. 1–11.

Castellano, M & Heitor Leal Machado 2017, ‘“Please Come to Brazil!” The Practices of RuPaul’s Drag Race’s Brazilian Fandom’, in N Brennan & D Gudelunas (eds), Springer eBooks, Palgrave Macmillan Cham, pp. 167–177.

McIntyre, J & Riggs, DW 2017, ‘North American Universalism in RuPaul’s Drag Race: Stereotypes, Linguicism, and the Construction of “Puerto Rican Queens”’, in N Brennan & D Gudelunas (eds), RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Shifting Visibility of Drag Culture, pp. 61–75.

Ouellette, L 2016, Lifestyle TV, Routledge.

Ouellette, L & Hay, J 2008, Better Living Through Reality TV, Wiley-Blackwell.

Straubhaar, JD 1991, ‘Beyond Media Imperialism: Assymetrical Interdependence and Cultural Proximity’, Critical Studies in Mass Communication, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 39–59.

Teresa, S-GT 2023, ‘Origen, aplicación y límites de la ”teoría del encuadre” (framing) en comunicación’, Handle.net, Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra, viewed 8 October 2023, https://hdl.handle.net/10171/7975.

Villarreal, NA de la G, García, CV & Fernández, GKR 2017, ‘Reception of Queer Content and Stereotypes Among Young People in Monterrey, Mexico: RuPaul’s Drag Race’, in D Gudelunas & N Brennan (eds), RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Shifting Visibility of Drag Culture, Palgrave Macmillan Cham, pp. 179–195.

0 notes

Text

1st Stop: Cirque du tumblr's Identity Performers

Anyone can be anyone on Tumblr. It is not hard to imagine a Capybara being a feminist social media researcher here.

Navigating this highly personalized landscape requires a specific type of subcultural capital (Clawson & Thornton 1997) to discover an alternate world—a queer, carnival-like atmosphere where diverse individuals converge over shared passions, desires, and identities. Comparable to a circus, Tumblr's pleasures are both vast and unpredictable; its heightened drama breathes life and inspiration into users, but occasionally takes an ugly turn and leaves wounds in its wake.

Who are you, and what are you doing on Tumblr?

Tumblr transcends the label of a mere platform; for many, it's a home, especially for the socially and politically disenfranchised. These counterpublics have their own audiences, develop their own language, and offer a circulating discourse that is oriented toward the future (Warner 2002). As a deinstitutionalized, underfunded, and countercultural space, Tumblr fosters alternative pleasures, education, resource sharing, and creative and critical work.

However, the freedom and spontaneity of Tumblr come with a double-edged sword, allowing for misunderstandings, misrepresentation, harassment, plagiarism, trolling, and threats. While celebrated as a "social justice" platform, some researchers view it more as a network, a "contact zone," or even a "landmine" than a cohesive community (McCracken et al. 2020). Subcultures on Tumblr vary widely, with some far from progressive or empowering, condoning self-harm, promoting racism and transphobia, and turning inward in ways that are devastating. Unfortunately, the same "call-out culture" and social justice rhetoric that check privilege can be weaponized to hurt, ridicule, and dehumanize others (Mccracken 2017).

The Home for Double-life Performers

“The magic of Tumblr is we let you put anything in and get it out any way you want.” - David Karp

Tumblr's design and aesthetics have left an indelible mark on social media and popular culture in the 2010s.

Its features encourage heartfelt confessions, heated discussions, and dreamy creations, with the only boundary being one's imagination. Understanding Tumblr's social dynamics and its value requires recognizing it as a space affording young people a particular kind of social privacy aligned with their believes, than the more conventionally prioritized informational privacy. This stands in contrast to mainstream spaces like Facebook, which are more tightly integrated with offline lives, norms, and practices.

Drawing from Judith Butler's ideas of performativity (1988), which suggest that identity is not something inherently fixed but is instead performed and constructed through social and cultural practices, Tumblr users engage in digital identity performance—curating content, creating original posts, and interacting with others. The platform becomes a space for individuals to express nuanced and complex identities with dual lives—online and offline.

Tumblr embodies postmodern ideals as users navigate a space where traditional hierarchies and structures are often deconstructed. The emphasis on user-generated content and the blending of various media forms contribute to the creation of hyperrealities. The platform's interface attracted users seeking creative agency and an egalitarian, nonhierarchical, uncensored media environment. Adopting pseudonyms and high personalization allowed users to change identities at will, providing a protective opacity to separate online life from work and personal spheres. Tumblr's content pool, notably broader than other platforms, historically permitted adult sexual content (Ashley 2019), and users largely ignored commercial copyrights. In essence, Tumblr granted users control over what to post, how their blog looked, its connection to real life, and the ongoing presence and identity of their online persona.

Many people, therefore, view life on Tumblr as their second life, especially teenagers with privacy pervading issues within their own homes. The fact that the most significant threats to young people’s ability to manage social privacy typically come from within the “private sphere” of the home and close aquaintances often leads them to seek out moments of privacy in “public” spaces like Tumblr, where—despite the presence of a much larger potential audience—they find that they can exert more personal agency over information about themselves because no unwanted audience is (usually) paying specific attention to them (Marwick & boyd 2014).

Of course, it does not always turn out that way. At the end, this place is like a circus with loads of strangers having the same burdens and mental states.

Reference

Ashley, V 2019, ‘Tumblr porn eulogy’, Porn Studies, pp. 1–4.

Butler, J 1988, ‘Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: an Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory’, Theatre Journal, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 519–531.

Clawson, MA & Thornton, S 1997, ‘Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital’, Contemporary Sociology, vol. 26, no. 4, p. 510.

Marwick, AE & boyd, danah 2014, ‘Networked privacy: How teenagers negotiate context in social media’, New Media & Society, vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 1051–1067.

Mccracken, A 2017, ‘Tumblr Youth Subcultures and Media Engagement’, Cinema Journal, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 151–161.

McCracken, A, Cho, A, Stein, L & Hoch, IN 2020, a tumblr book: platform and cultures, University of Michigan Press, viewed 2 February 2024, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11537055.

Nunes, M 1995, ‘Jean Baudrillard in Cyberspace: Internet, Virtuality, and Postmodernity’, Style, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 314–327.

Warner, M 2002, ‘Publics and Counterpublics’, Public Culture, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 49–90.

Wu, T 2013, ‘David Karp Is Tumblr’s Reluctant Technologist’, The New York Times, 11 September.

0 notes

Text

I hate orange, he is effing racist

1 note

·

View note