Text

8 Signs your Sequel Needs Work

Sequels, and followup seasons to TV shows, can be very tricky to get right. Most of the time, especially with the onslaught of sequels, remakes, and remake-quels over the past… 15 years? There’s a few stand-outs for sure. I hear Dune Part 2 stuck the landing. Everyone who likes John Wick also likes those sequels. Spiderverse 2 also stuck the landing.

These are less tips and more fundamental pieces of your story that may or may not factor in because every work is different, and this is coming from an audience’s perspective. Maybe some of these will be the flaws you just couldn’t put your finger on before. And, of course, these are all my opinions, for sequels and later seasons that just didn’t work for me.

1. Your vague lore becomes a gimmick

The Force, this mysterious entity that needs no further explanation… is now quantifiable with midichlorians.

In The 100, the little chip that contains the “reincarnation” of the Commanders is now the central plot to their season 6 “invasion of the bodysnatchers” villains.

In The Vampire Diaries, the existence of the “emotion switch” is explicitly disputed as even existing in the earlier seasons, then becomes a very real and physical plot point one can toggle on and off.

I love hard magic systems. I love soft magic systems, too. These two are not evolutions of each other and doing so will ruin your magic system. People fell in love with the hard magic because they liked the rules, the rules made sense, and everything you wrote fit within those rules. Don’t get wacky and suddenly start inventing new rules that break your old ones.

People fell in love with the soft magic because it needed no rules, the magic made sense without overtaking the story or creating plot holes for why it didn’t just save the day. Don’t give your audience everything they never needed to know and impose limitations that didn’t need to be there.

Solving the mystery will never be as satisfying as whatever the reader came up with in their mind. Satisfaction is the death of desire.

2. The established theme becomes un-established

I talked about this point already in this post about theme so the abridged version here: If your story has major themes you’ve set out to explore, like “the dichotomy of good and evil” and you abandon that theme either for a contradictory one, or no theme at all, your sequel will feel less polished and meaningful than its predecessor, because the new story doesn’t have as much (if anything) to say, while the original did.

Jurassic Park is a fantastic, stellar example. First movie is about the folly of human arrogance and the inherent disaster and hubris in thinking one can control forces of nature for superficial gains. The sequels, and then sequel series, never returns to this theme (and also stops remembering that dinosaurs are animals, not generic movie monsters). JP wasn’t just scary because ahhh big scary reptiles. JP was scary because the story is an easily preventable tragedy, and yes the dinosaurs are eating people, but the people only have other people to blame. Dinosaurs are just hungry, frightened animals.

Or, the most obvious example in Pixar’s history: Cars to Cars 2.

3. You focus on the wrong elements based on ‘fan feedback’

We love fans. Fans make us money. Fans do not know what they want out of a sequel. Fans will never know what they want out of a sequel, nor will studios know how to interpret those wants. Ask Star Wars. Heck, ask the last 8 books out of the Percy Jackson universe.

Going back to Cars 2 (and why I loathe the concept of comedic relief characters, truly), Disney saw dollar signs with how popular Mater was, so, logically, they gave fans more Mater. They gave us more car gimmicks, they expanded the lore that no one asked for. They did try to give us new pretty racing venues and new cool characters. The writers really did try, but some random Suit decided a car spy thriller was better and this is what we got.

The elements your sequel focuses on could be points 1 or 2, based on reception. If your audience universally hates a character for legitimate reasons, maybe listen, but if your audience is at war with itself over superficial BS like whether or not she’s a female character, or POC, ignore them and write the character you set out to write. Maybe their arc wasn’t finished yet, and they had a really cool story that never got told.

This could be side-characters, or a specific location/pocket of worldbuilding that really resonated, a romantic subplot, whatever. Point is, careening off your plan without considering the consequences doesn’t usually end well.

4. You don’t focus on the ‘right’ elements

I don’t think anyone out there will happily sit down and enjoy the entirety of Thor: The Dark World. The only reasons I would watch that movie now are because a couple of the jokes are funny, and the whole bit in the middle with Thor and Loki. Why wasn’t this the whole movie? No one cares about the lore, but people really loved Loki, especially when there wasn’t much about him in the MCU at the time, and taking a villain fresh off his big hit with the first Avengers and throwing him in a reluctant “enemy of my enemy” plot for this entire movie would have been amazing.

Loki also refuses to stay dead because he’s too popular, thus we get a cyclical and frustrating arc where he only has development when the producers demand so they can make maximum profit off his character, but back then, in phase 2 world, the mystery around Loki was what made him so compelling and the drama around those two on screen was really good! They bounced so well off each other, they both had very different strengths and perspectives, both had real grievances to air, and in that movie, they *both* lost their mother. It’s not even that it’s a bad sequel, it’s just a plain bad movie.

The movie exists to keep establishing the Infinity Stones with the red one and I can’t remember what the red one does at this point, but it could have so easily done both. The powers that be should have known their strongest elements were Thor and Loki and their relationship, and run with it.

This isn’t “give into the demands of fans who want more Loki” it’s being smart enough to look at your own work and suss out what you think the most intriguing elements are and which have the most room and potential to grow (and also test audiences and beta readers to tell you the ugly truth). Sequels should feel more like natural continuations of the original story, not shameless cash grabs.

5. You walk back character development for ~drama~

As in, characters who got together at the end of book 1 suddenly start fighting because the “will they/won’t they” was the juiciest dynamic of their relationship and you don’t know how to write a compelling, happy couple. Or a character who overcame their snobbery, cowardice, grizzled nature, or phobia suddenly has it again because, again, that was the most compelling part of their character and you don’t know who they are without it.

To be honest, yeah, the buildup of a relationship does tend to be more entertaining in media, but that’s also because solid, respectful, healthy relationships in media are a rarity. Season 1 of Outlander remains the best, in part because of the rapid growth of the main love interest’s relationship. Every season after, they’re already married, already together, and occasionally dealing with baby shenanigans, and it’s them against the world and, yeah, I got bored.

There’s just so much you can do with a freshly established relationship: Those two are a *team* now. The drama and intrigue no longer comes from them against each other, it’s them together against a new antagonist and their different approaches to solving a problem. They can and should still have distinct personalities and perspectives on whatever story you throw them into.

6. It’s the same exact story, just Bigger

I have been sitting on a “how to scale power” post for months now because I’m still not sure on reception but here’s a little bit on what I mean.

Original: Oh no, the big bad guy wants to destroy New York

Sequel: Oh no, the big bad guy wants to destroy the planet

Threequel: Oh no, the big bad guy wants to destroy the galaxy

You knew it wasn’t going to happen the first time, you absolutely know it won’t happen on a bigger scale. Usually, when this happens, plot holes abound. You end up deleting or forgetting about characters’ convenient powers and abilities, deleting or forgetting about established relationships and new ground gained with side characters and entities, and deleting or forgetting about stakes, themes, and actually growing your characters like this isn’t the exact same story, just Bigger.

How many Bond movies are there? Thirty-something? I know some are very, very good and some are not at all good. They’re all Bond movies. People keep watching them because they’re formulaic, but there’s also been seven Bond actors and the movies aren’t one long, continuous, self-referential story about this poor, poor man who has the worst luck in the universe. These sequels aren’t “this but bigger” it’s usually “this, but different”, which is almost always better.

“This, but different now” will demand a different skillset from your hero, different rules to play by, different expectations, and different stakes. It does not just demand your hero learn to punch harder.

Example: Lord Shen from Kung Fu Panda 2 does have more influence than Tai Lung, yes. He’s got a whole city and his backstory is further-reaching, but he’s objectively worse in close combat—so he doesn’t fistfight Po. He has cannons, very dangerous cannons, cannons designed to be so strong that kung fu doesn’t matter. Thus, he’s not necessarily “bigger” he’s just “different” and his whole story demands new perspective.

The differences between Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi are numerous, but the latter relies on “but bigger” and the former went in a whole new direction, while still staying faithful to the themes of the original.

7. It undermines the original by awakening a new problem too soon

I’ve already complained about the mere existence of Heroes of Olympus elsewhere because everything Luke fought and died for only bought that world about a month of peace before the gods came and ripped it all away for More Story.

I’ve also complained that the Star Wars Sequels were always going to spit in the face of a character’s six-movie legacy to bring balance to the Force by just going… nah. Ancient prophecy? Only bought us about 30 years of peace.

Whether it’s too soon, or it’s too closely related to the original, your audience is going to feel a little put-off when they realize how inconsequential this sequel makes the original, particularly in TV shows that run too many seasons and can’t keep upping the ante, like Supernatural.

Kung Fu Panda once again because these two movies are amazing. Shen is completely unrelated to Tai Lung. He’s not threatening the Valley of Peace or Shifu or Oogway or anything the heroes fought for in the original. He’s brand new.

My yearning to see these two on screen together to just watch them verbally spat over both being bratty children disappointed by their parents is unquantifiable. This movie is a damn near perfect sequel. Somebody write me fanfic with these two throwing hands over their drastically different perspectives on kung fu.

8. It’s so divorced from the original that it can barely even be called a sequel

Otherwise known as seasons 5 and 6 of Lost. Otherwise known as: This show was on a sci-fi trajectory and something catastrophic happened to cause a dramatic hairpin turn off that path and into pseudo-biblical territory. Why did it all end in a church? I’m not joking, they did actually abandon The Plan while in a mach 1 nosedive.

I also have a post I’ve been sitting on about how to handle faith in fiction, so I’ll say this: The premise of Lost was the trials and escapades of a group of 48 strangers trying to survive and find rescue off a mysterious island with some creepy, sciency shenanigans going on once they discover that the island isn’t actually uninhabited.

Season 6 is about finding “candidates” to replace the island’s Discount Jesus who serves as the ambassador-protector of the island, who is also immortal until he’s not, and the island becomes a kind of purgatory where they all actually did die in the crash and were just waiting to… die again and go to heaven. Spoiler Alert.

This is also otherwise known as: Oh sh*t, Warner Bros wants more Supernatural? But we wrapped it up so nicely with Sam and Adam in the box with Lucifer. I tried to watch one of those YouTube compilations of Cas’ funny moments because I haven’t seen every episode, and the misery on these actors’ faces as the compilation advanced through the seasons, all the joy and wit sucked from their performances, was just tragic.

I get it. Writers can’t control when the Powers That Be demand More Story so they can run their workhorse into the ground until it stops bleeding money, but if you aren’t controlled by said powers, either take it all back to basics, like Cars 3, or just stop.

—

Sometimes taking your established characters and throwing them into a completely unrecognizable story works, but those unrecongizable stories work that much harder to at least keep the characters' development and progression satisfying and familiar. See this post about timeskips that take generational gaps between the original and the sequel, and still deliver on a satisfying continuation.

TLDR: Sequels are hard and it’s never just one detail that makes them difficult to pull off. They will always be compared to their predecessors, always with the expectations to be as good as or surpass the original, when the original had no such competition. There’s also audience expectations for how they think the story, lore, and relationships should progress. Most faults of sequels, in my opinion, lie in straying too far from the fundamentals of the original without understanding why those fundamentals were so important to the original’s success.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Don't Need an Agent! Publishers That Accept Unsolicited Submissions

I see a few people sayin that you definitely need an agent to get published traditionally. Guess what? That's not remotely true. While an agent can be a very useful tool in finding and negotiating with publishers, going without is not as large of a hurdle as people might make it out to be!

Below is a list of some of the traditional publishers that offer reading periods for agent-less manuscripts. There might be more! Try looking for yourself - I promise it's not that scary!

Albert Whitman & Company: for picture books, middle-grade, and young adult fiction

Hydra (Part of Random House): for mainly LitRPG

Kensington Publishing: for a range of fiction and nonfiction

NCM Publishing: for all genres of fiction (YA included) and nonfiction

Pants of Fire Press: for middle-grade, YA, and adult fiction

Tin House Books: very limited submission period, but a good avenue for fiction, literary fiction, and poetry written by underrepresented communities

Quirk Fiction: offers odd-genre rep for represented and unagented authors. Unsolicited submissions inbox is closed at the moment but this is the page that'll update when it's open, and they produced some pretty big books so I'd keep an eye on this

Persea Books: for lit fiction, creative nonfiction, YA novels, and books focusing on contemporary issues

Baen: considered one of the best known publishers of sci-fi and fantasy. They don't need a history of publication.

Chicago Review Press: only accepting nonfiction at the moment, but maybe someone here writes nonfiction

Acre: for poetry, fiction and nonfiction. Special interest in underrepresented authors. Submission period just passed but for next year!

Coffeehouse Press: for lit fiction, nonfiction, poetry and translation. Reading period closed at time of posting, but keep an eye out

Ig: for queries on literary fiction and political/cultural nonfiction

Schaffner Press: for lit fiction, historical/crime fiction, or short fiction collections (cool)

Feminist Press: for international lit, hybrid memoirs, sci-fi and fantasy fiction especially from BIPOC, queer and trans voices

Evernight Publishing: for erotica. Royalties seem good and their response time is solid

Felony & Mayhem: for literary mystery fiction. Not currently looking for new work, but check back later

This is all what I could find in an hour. And it's not even everything, because I sifted out the expired links, the repeat genres (there are a lot of options for YA and children's authors), and I didn't even include a majority of smaller indie pubs where you can really do that weird shit.

A lot of them want you to query, but that's easy stuff once you figure it out. Lots of guides, and some even say how they want you to do it for them.

Not submitting to a Big 5 Trad Pub House does not make you any less of a writer. If you choose to work with any publishing house it can take a fair bit of weight off your shoulders in terms of design and distribution. You don't have to do it - I'm not - but if that's the way you want to go it's very, very, very possible.

Have a weirder manuscript that you don't think fits? Here's a list of 50 Indie Publishers looking for more experimental works to showcase and sell!

If Random House won't take your work - guess what? Maybe you're too cool for Random House.

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other day, I went down the rabbit hole of "cute donkeys" and came up with my head full of things I didn't know about mules (the hybrid offspring of a horse and a donkey), and why they were once so coveted as work animals.

Brace for info dump, while enjoying this lovely photo of a trio of draft mules.

The explanation is hybrid vigour, when hybrid offspring have enhanced traits compared to its parents:

Mules are stronger, hardier, healthier, have better enduranve, harder hooves, sturdier skin and can handle extreme weather better than horses or donkeys. They are also more patient, more intelligent, and easier to handle than either of their parent species. Horses may be faster, but that's about the single thing they're better at than a mule of the same size.

So mules, being all around nicer to work with and getting you more work for the same amount of feed, and with less hassle, were preferred for just about every job purpose.

Habby du Magnou, a Poitevin Mulassier mare, and her daughter Lady du Magnou, a rare Poitevin mule

But since horses have 64 chromosomes and donkeys have 62, mules end up with 63 chromosomes, which means they are almost invariably sterile. That's because biology gets very confused when trying to split an uneven number of chromosomes neatly in half to create germ cells. There are a few documented exceptions of fertile mule mares (never stallions), but they are very, very rare. So you have to keep crossbreeding the two parent species to produce them, usually by breeding a donkey sire (jack) to a horse dam (mare). This is because it's easier for a 32 chromosome egg to incorporate a 31 chromosome sperm into a viable zygote (fertilised egg) than vice versa.

Because of this, there was (and still is) in France a breed of absolutely massive draft horses, the Poitevin Mulassier, and a breed of big-ass donkeys (pun intended, but honestly, it's arguably the largest donkey in the world, and it's shaggy like Highland cattle), the Baudet du Pitou, two breeds whose main purpose was to breed the enormous and super-strong Poitevin mule.

The Poitevin mule

This absolute unit was the must-have work-animal for all kinds of farm and industrial work for centuries, and a significant French export, until mechanisation made these magnificent creatures obsolete.

With no demand for the Poitevin mule , its parent breeds dwindled, almost to the brink of extinction. Determined conservation efforts during the last few decades are slowly bringing their numbers back up, but they're very far from their heyday, when some 20,000 Poitevin mules were born annually.

The Poitevin Mulassier

Both the parent breeds are still endangered, which means most of the current effort is directed into bringing up the numbers of Poitevin horses and Pitou donkeys. This means breeding horses to horses and donkeys to donkeys, with very few breeding opportunities allowed to produce the Poitevin mule. Only about 20 of those are born each year.

The Baudet du Pitou

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

What No One Tells You About Writing Fantasy

Every author has their preferred genres. I love fantasy and sci-fi, but began with historical fiction. I hated all the research that historical fiction demands and thought, if I build my own world, no research required.

Boy, was I wrong.

So to anyone dipping their toe into fantasy/sci-fi, here’s seven things I wish I knew about the genres before I committed to writing for them.

1. You still have to research. Everything.

If you want any of your fantasy battle sequences, or your space ships, or your droids and robots, or your fictional government and fictional politics to read at all believable.

In sci-fi, you research astronomy, robotics, politics, political science, history, engineering, anthropology. In fantasy, you have to research historical battle tactics, geography, real-world mythology, folklore, and fairytales, and much of it overlaps with science fiction.

I say you *have to* assuming you want your work to be original and unique and stand out from the crowd. Fanfic writers put in the research for a 30k word smut fic, you can and will have to research for your original work.

2. Naming everything gets exhausting

I hate coming up with new names, especially when I write worlds and places divorced from Earthly customs and can’t rely on Earthly naming conventions. You have to name all your characters, all your towns, villages, cities, realms, kingdoms, planets, galaxies, star systems.

You have to name your rebel faction, your imperial government, significant battles. Your spaceships, your fantasy companies and organizations, your magic system, made-up MacGuffins, androids, computer programs. The list goes on and on and on.

And you have to do it all without it sounding and reading ridiculous and unpronounceable, or racist. Your fantasy realms have to have believable naming patterns. It. Gets. Exhausting.

3. It will never read like you’re watching a movie

Do you know how fast movies can cut between scenes? Movies can balance five plotlines at once all converging with rapid edits, without losing their audience. Sometimes single lines of dialogue, or single wordless shots are all a scene gets before it cuts. If you try to replicate that by head-hopping around, you will make a mess.

It’s perfectly fine to write like you’re watching a movie, but you can’t rely on visual tricks to get your point across when all you have is text on a page – like slow mo, lens flares, epically lit cinematic shots, or the aforementioned rapid edits.

It doesn’t have to, nor should it, look like a movie. Books existed long before film, so don’t let yourself get caught up in how ~cinematic~ it may or may not look.

4. Your space opera will be compared to Star Wars and Star Trek

And your fairy epic will be compared to Tinkerbell, your vampires to Twilight, your zombies to The Walking Dead, Shaun of the Dead, World War Z. Your wizards and witches and any whisper of a fantasy school for fantasy children will be compared to Harry Potter. Your high fantasy adventure will be compared to Lord of the Rings.

You can’t avoid it, but you can avoid doing it to yourself. When people ask about your book, let them say “oh, you mean like Star Wars” to which you then can say, kind of, except XYZ happens in my book. These IPs will never fade from the public consciousness, not while you exist to read this post, at least, but Harry Potter isn’t the only urban fantasy out there. Lord of the Rings isn’t the only high fantasy. Star Wars isn’t the only space opera.

Yours will be on the shelves right next to them, soon enough, and who knows? You might dethrone them.

5. Your world-building is an iceberg, and your book is the tip

I don’t pay for any of those programs that help you organize your book and mythos. I write exclusively on Apple Notes, MS Word, and Google Suite (and all are free to me). I have folders on Apple Notes with more words inside them than the books they’re written for.

If you try to cram an entire college textbook’s worth of content into your novel, you will have left zero room for actual story. The same goes for all the research you did, all the hours slaving away for just a few details and strings of dialogue.

There’s a balance, no matter how dense your story is. If you really want to include all those extra details, slap some appendices at the end. Commission some maps.

6. The gatekeeping for fantasy and sci-fi is still very real

Pen names and pseudonyms exist for a reason. A female author writing fantasy that isn’t just a backdrop for romance? You have a harder battle ahead of you than your male counterparts, at least in the US. And even then, your female protagonist will be scrutinized and torn apart.

She’ll either be too girly or not girly enough, too sexy, or not sexy enough. She’ll be called a Mary Sue, a radical feminist mouthpiece, some woke propaganda. Every action she takes will be criticized as unrealistic and if she has fans who are girls, they will be mocked, too.

If you have queer characters, characters of color, they won’t be good enough, they won’t please everyone, and someone will still call you a bigot. A lot of someones will still call you a bigot.

Do your due diligence and hire your army of sensitivity readers and listen to them, but you cannot please everyone, so might as well write to please yourself. You’re the one who will have to read it a thousand times until it’s published.

7. Your “original” idea has been done before, and that’s okay

Stories have been told since before language evolved. The sum of the parts of your novel may be original, but even then, it’s colored by the media you’ve consumed. And that’s okay!

How many Cinderella stories are there? How many high fantasies? How many books about werewolves and witches and vampires? Gods and goddesses and celestial beings? Fairies and dragons and trolls? Aliens, robots, alien robots? Romeo and Juliette? Superheroes and mutants?

Zombies may be the avenue through which you tell your story, but it’s not *just* about zombies, is it? It’s about the characters who battle them, the endurance of the human spirit, or the end of an era, the death of a nation. So don’t get discouraged, everyone before you and everyone after will have written someone on the backs of what came before and it still feels new.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Mental Health With Compassion

I've gotten a few questions regarding depicting characters with mental health challenges and conditions and I wanted to expand a little more on how to depict these characters with compassion for the real communities represented by these characters.

A little about this guide: this is, as always, coming from a place of love and respect for the writing community and the groups affected by this topic at large. I'm also not coming at this from the outside, I have certain mental illnesses that affect my daily life. With that, I'll say that my perspective may be biased, and as with all writing advice, you should think critically about what is being told to you and how.

So let's get started!

Research

I'm sure we're all tired of hearing the phrase "do your research," but unfortunately it is incredibly important advice. I have a guide that touches on how to do research here, if you need a place to get started.

When researching a mental health condition that we do not experience, we need to do so critically, and most importantly, compassionately. While your characters are not people, they are assigned traits that real people do have, and so your depiction of these traits can have an impact on people who face these conditions themselves.

I've found that reddit is a decent resource for finding threads of people talking about their personal experiences with certain illnesses. For example, bipolar disorder has several subreddits that have very open and candid discussions about bipolar, how it impacts lives, and small things that people who don't have bipolar don't tend to think about.

It's important to note that these spaces are not for you. They are spaces for people to talk about their experiences in a place without judgment or fear or stigma. These are not places for people to give out writing advice. Do NOT flood subreddits for people seeking support with questions that may make others feel like an object to be studied. It's not cool or fair to them for writers to enter their space and start asking questions when they're focused on getting support. Be courteous of the people around you.

Diagnosis

I have the belief that for most stories, a diagnosis for your characters is unnecessary. I have a few reasons for thinking this way.

Firstly, mental health diagnoses are important for treatment, but they're also a giant sign written across your medical documents that says, “I'm crazy!” Doctors may try to remain unbiased when they see mental health diagnoses, but anybody with a diagnosis can say that doctors rarely succeed. This translates to a lot of people never getting diagnoses, never seeking treatment, or refusing to talk about their diagnosis if they do have one.

Secondly, I've seen posts discuss “therapy speak” in fiction, and this is one of those instances where a diagnosis and extensive research may make you vulnerable to it. People don't tend to discuss their diagnoses freely and they certainly don't tend to attribute their behaviors as symptoms.

Finally, this puts you, the writer, into a position where you treat your characters less like people and story devices and more like a list of symptoms and behavioral quirks. First and foremost, your characters serve your story. If they don't feel like people then your characters may fall flat. When it comes to mental illness in characters, the people aspect is the most important part. Mentally ill people are people, not symptoms.

Those are my top three reasons for believing that most characters will never need a specific diagnosis. You will likely never need to depict the difference between bipolar and borderline because the story itself does not need that distinction or to reveal a diagnosis at all. I feel that having a diagnosis in mind for a character has more pitfalls than advantages.

How does treatment work?

Treating mental health conditions may appear in your story. There are a number of ways treatments affect daily life and understanding the levels of care and what those levels treat will help you depict the appropriate settings for your characters.

The levels of care range from minimally restrictive and minimal care to intensive in-patient care in a secure hospital setting.

Regular or semi-regular therapy is considered outpatient care. This is generally the least restrictive. Your characters may or may not also take medications, in which case they may also see a psychiatrist to prescribe those medications. There is a difference between therapists, psychiatrists, and psychologists. Therapists do not prescribe medications, psychiatrists prescribe medications after an evaluation, and psychologists will (sometimes) do both. (I'm US, so this may work differently depending where you are. You should always research the specific setting of your story.) Generally, a person with a mental illness or mental health condition will see both an outpatient therapist and an outpatient psychiatrist for their general continuing care.

Therapists will see their patients anywhere from once in a while as-needed to twice weekly. Psychiatrists will see new patients every few weeks until they report stabilizing results, and then they will move to maintenance check-ins every 90-ish days.

If the patient reports severe symptoms, or worsening symptoms, they will be moved up to more intensive care, also known as IOP (Intensive Outpatient Program). This is usually a group-therapy setting for between 3-7 hours per day between 3-5 days a week. The group-therapy is led by a Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC) or Licensed Professional Social Worker (LPSW). Groups are structured sessions with multiple patients teaching coping mechanisms and focusing on treatment adjustment. IOP’s tend to expect patients to see their own outpatient psychiatrist, but I've encountered programs that have their own in-house psychiatrists.

If the patient still worsens, or is otherwise needing more intensive care, they'll move up to PHP (Partial Hospitalization Program). This can look different per facility, but I've seen them to be more intensive in hours and content than IOP. They also usually have in-house psychiatrists doing diagnostic psychological evaluations. It's very possible for characters with “mild” symptoms to go long periods of time, even most of their lives, without having had a diagnosis. PHP’s tend to need a diagnosis so that they can address specific concerns and help educate the patient on their condition and how it may manifest.

Next step up is residential care. Residential care is a boarding hospital setting. Patients live in the hospital and focus entirely on treatment. Individual programs may differ in what's allowed in, how much contact the patients are allowed to have, and what the treatment focus is. Residential programs are often utilized for addiction recovery. Good residential programs will care about the basis for the addiction, such as underlying mental health issues that the patient may be self-medicating for. Your character may come away with a diagnosis, or they may not. Residential programs aren't exclusively for addictions though, and can be useful for severe behavioral concerns in teenagers or any number of other concerns a patient may have that manifest chronically but do not require intensive inpatient restriction.

Inpatient hospital stays are the highest level of care, and this tends to be what people are talking about when they tell jokes about “grippy socks.” These programs are inside the hospital and patients are highly restricted on what they can and cannot have, they cannot leave unless approved by the hospital staff (the hospital's psychiatrist tends to have the final say), and contact with the outside world is highly regulated. During the days, there are group therapy sessions and activities structured very carefully to maintain routine. Staff will regulate patient hygiene, food and sleep routines, and alone time.

Inpatient hospital programs are controversial among people with mental illness and mental health concerns. I find that they have use, but they are also not an easy or first step to take when dealing with a mental health condition. Patients are not allowed sharp objects, metal objects, shoelaces, cutlery, and pens or pencils. Visitors are not allowed to bring these items in, staff are not allowed these items either. This is for the safety of the patients. Typically, if someone is involuntarily admitted into the inpatient hospital program, it is due to an authority (the hospital staff) deeming the patient as a danger to themselves or others. Whether they came in of their own will (voluntary) or not does not matter in how the program operates. Everyone is treated the same. If someone is an active danger to themselves, then they may be on 24-hour suicide watch. They are not allowed to have any time alone. No, not even for the bathroom, or while sleeping, or during group sessions.

Inpatient Hospital Programs

This is a place of high curiosity for those who have never been admitted into inpatient care, so I'd like to explain a little more in detail how these programs work, why they're controversial, but how they can be useful in certain situations. I do have personal experience in this area, but as always, your mileage may vary.

When admitting, hospital staff are the final say. Not the police. The police hold some sway, but most often, if someone is brought in by the police, they are likely to be admitted. They are only involuntarily admitted when the situation demands: the staff have determined the person to be an imminent danger to themselves or others. This is obviously subjective, and can easily be abused. A good program with decent staff will do everything they can to convince the patient to admit voluntarily if they feel it is necessary, but ultimately if the patient declines and the staff don't feel they can make the clinical argument that admittance is necessary, the patient is free to leave. It should be noted that doctors and clinicians have to worry about possibly losing their licenses to practice. They don't want to fuck around with involuntary admittance if they don't have to, and they don't want potentially dangerous people to walk away.

Once admitted, the patient will have to remove their clothing and put on a set of hospital scrubs. These are mostly made of paper, and most often do not have pockets, but I have seen sets that do have pockets (very handy, tbh). They are not allowed to take anything into the hospital wing except disability-required devices such as glasses, hearing aids, mobility aids, etc. Most programs will require removing piercings, but not all of them, in my experience.

The nurses will also do a physical examination, where they will make note of any open wounds, major scars, tattoos, and other skin abrasions that may be relevant.

The patient will then be led to their bed, where they will receive any approved clothing items from outside, a copy of their patient rights, and a copy of the floor code of conduct and rules, a schedule, and any other administrative information necessary for the program to run efficiently and legally.

Group sessions include group-therapy, activities, coping skills, anger management, anxiety management, and for some reason, karaoke. There is a lot of coloring involved, but only with crayons. A good program will focus heavily on skills and therapeutic activities. Bad programs will phone it in and focus on karaoke and activities. Most hospitals will have a chaplain, and some will include a religious group session. I've never attended these, so I can't speak for them.

Unspoken rules are the hidden pieces of the inpatient programs that patients tend to find out during their first visit. There is no leaving the program until the doctor agrees to it. The doctor will only agree to it if they deem you ready to leave, and you are only ready to leave if you have been compliant to treatment and have seen positive results in the most dangerous symptoms (homicidal or suicidal ideations). Noncompliance can look like: refusing your prescribed medications (which you have the right to do at any time for any reason. That does not mean that there won't be consequences. This is a particularly controversial point.), refusing to attend groups (chapel is not included in this point, but that doesn't mean it's actually discounted. Another controversial point.), violent or disruptive outbursts such as yelling or throwing things, and refusing to sleep or eat at the approved and appointed times. All of this may sound like the hospital is restricting your rights beyond reason, but I've seen the use, and I've seen the abuse. Medications are sometimes necessary, and often patients seriously prefer having medication. Groups are important to a person's treatment, and refusing to go can be a sign of noncompliance or worsening symptoms. If someone is too depressed or anxious to go to group, then they're probably not ready to leave the hospital where the structure is gone and they must self-regulate their treatment. Violent or disruptive outbursts tend to be a sign of worsening symptoms in general, but even the best of us lose our tempers from time to time when put into a highly stressful situation like an inpatient hospital stay. The hospital is supposed to be a place of healing, for many it is. But for many more, it is a place of systematic abuse and restriction.

Discharge processes can be long and arduous and INCREDIBLY stressful for the patient. Oftentimes, they won't know their discharge date until the day of, or perhaps the day before. Though the date can change at any time. The discharge process requires the supervising psychiatrist to meet with the treatment team and then the patient to determine if the patient had progressed enough to be safely discharged. Discharge also requires a set outpatient plan in place, such as a therapy appointment within a week, a psychiatrist visit, or admittance into a lower level of care. This is where social workers are involved. Patients are not allowed access to cell phones or the internet. They cannot make their own appointments with their outpatient care providers without a phone number and phone access. Some floors will have phone access for this reason, others will insist the social worker arrange appointments and discharge plans. Social workers are often incredibly overworked, with several patients on their caseload.

The patient cannot be discharged until the social worker has coordinated the discharge plan to the doctor's approval. Most often, unfortunately, the patient rarely receives regular communication regarding the progress of their discharge. I've been discharged with as much as a day's notice to two hours notice.

Part 2 Coming Soon

This guide got longer than expected! Out of respect for my followers dashboard, I will be cutting it here and adding a Part 2 later on.

If you find that there are more specific questions you'd like answered, or topics you'd like covered, send an ask or reply to this post with what you'd like to see in Part 2.

– Indy

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Person: What's your book about?

Writers:

I'm both somehow 🙃

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pro-writing tip: if your story doesn't need a number, don't put a fucking number in it.

Nothing, I mean nothing, activates reader pedantry like a number.

I have seen it a thousand times in writing workshops. People just can't resist nitpicking a number. For example, "This scifi story takes place 200 years in the future and they have faster than light travel because it's plot convenient," will immediately drag every armchair scientist out of the woodwork to say why there's no way that technology would exist in only 200 years.

Dates, ages, math, spans of time, I don't know what it is but the second a specific number shows up, your reader is thinking, and they're thinking critically but it's about whether that information is correct. They are now doing the math and have gone off drawing conclusions and getting distracted from your story or worse, putting it down entirely because umm, that sword could not have existed in that Medieval year, or this character couldn't be this old because it means they were an infant when this other story event happened that they're supposed to know about, or these two events now overlap in the timeline, or... etc etc etc.

Unless you are 1000% certain that a specific number is adding to your narrative, and you know rock-solid, backwards and forwards that the information attached to that number is correct and consistent throughout the entire story, do yourself a favor, and don't bring that evil down upon your head.

82K notes

·

View notes

Text

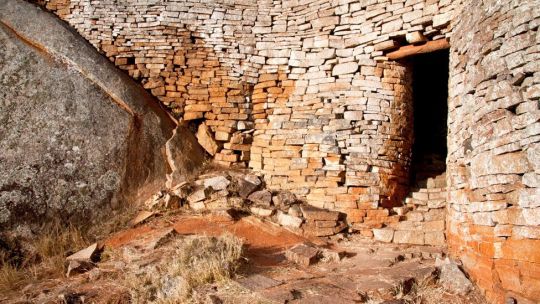

BBC: The ancient remains of Great Zimbabwe

The ancient city of Great Zimbabwe was an engineering wonder. But archaeologists credited it to Phoenicians, Babylonians, Arabians – anyone but the Africans who actually built it.

W

Walking up to the towering walls of Great Zimbabwe was a humbling experience. The closer I got, the more they dwarfed me – and yet, there was something inviting about the archaeological site. It didn't feel like an abandoned fortress or castle that one might see in Europe: Great Zimbabwe was a place where people lived and worked, a place where they came to worship – and still do. It felt alive.

Great Zimbabwe is the name of the extensive stone remains of an ancient city built between 1100 and 1450 CE near modern-day Masvingo, Zimbabwe. Believed to be the work of the Shona (who today make up the majority of Zimbabwe's population) and possibly other societies that were migrating back and forth across the area, the city was large and powerful, housing a population comparable to London at that time – somewhere around 20,000 people during its peak. Great Zimbabwe was part of a sophisticated trade network (Arab, Indian and Chinese trade goods were all found at the site), and its architectural design was astounding: made of enormous, mortarless stone walls and towers, most of which are still standing.

However, for close to a century, European colonisers of the late-19th and early-20th Centuries attributed the construction to outsiders and explorers, rather than to the Africans themselves.

Indeed, the author of the first written European record of Great Zimbabwe seemed to be staggered by the very idea that it could have been built at all. Portuguese explorer Joao de Barros wrote in 1552 that, "There is masonry within and without, built of stones of a marvellous size, and there appears to be no mortar joining them."

Built between 1100 and 1450 CE, Great Zimbabwe was large and powerful (Credit: evenfh/Getty Images)

In the Shona language, zimbabwe translates approximately to "stone house", and because of the site's size and scope, it became known as Great Zimbabwe. Moreover, it was not the only such "Zimbabwe": there are remains of approximately 200 smaller settlements or trading posts spread across the region, from the Kalahari Desert in Namibia to Mozambique.

According to Munyaradzi Manyanga, a professor of archaeology and cultural heritage at Great Zimbabwe University, the position of Great Zimbabwe among these settlements has been widely debated. Some people have speculated that it was a capital city of a very large state, but to Manyanga, that seems unlikely. "Such a state would have been too large. One wouldn't have been able to manage that kind of extent and size. So most of the interpretations talk of these as having been influenced by Great Zimbabwe." He added that the Kingdom of Zimbabwe is considered to be made up of Great Zimbabwe and the smaller settlements located closer to it.

The walls, which are made of granite, are stacked precisely and do not use any mortar to hold them in place (Credit: 2630ben/Getty Images)

The walls, which are made of granite, are stacked precisely and do not use any mortar to hold them in place. "The quarrying of the granite, taking advantage of natural processes of weathering and the shaping of it into regular blocks was a major engineering undertaking by these pre-colonial communities," Manyganga said. Iron metallurgy was needed to make the tools required to cut the blocks; it was also needed to make trade goods subsequently found at the site. All of this points to a highly organised and technologically advanced society.

The population of Great Zimbabwe began to decline in the mid-15th Century as the Kingdom of Zimbabwe weakened (possible theories for the decline include a drop in mining output, overgrazing by cattle, and depleted resources), but the site itself was not abandoned. Manyganga explained that it was regularly visited by different Shona groups for spiritual reasons right up until colonisation by the British in the late 19th Century.

Europeans of the late-19th and early-20th Centuries attributed the construction to outsiders and explorers, rather than to the Africans (Credit: Agostini/Getty Images)

A decade later, in a speech to the Royal Geographic Society, British journalist Richard N Hall supported Bent's perspective after visiting the site himself. He talked about the artistic value of soapstone carvings that had been unearthed and the "marvellous cleverness" of a gold-mining operation that spanned hundreds of mines, before concluding that "it is quite a moral certainty that even the cruder methods of [these sciences'] application were imported from the Near East, and did not originate in South-East Africa." Instead, he and his colleagues held that Phoenicians, Arabians or Babylonians created the city.

According to Manyanga, "They wanted to use [this explanation] as a moral justification for colonising Zimbabwe. If there was this long-lost civilisation in this part of the world, there was nothing wrong with colonialism because they were resuscitating this old kingdom."

However, a few archaeologists of the time countered that the site was not nearly old enough to be from Biblical times. "The then-colonial government suppressed these views, and the official narrative in public media and museums was that Great Zimbabwe was of foreign origins," said Manyanga. This version of history was upheld through the 1960s and 1970s by the white-minority government of the colony. Only in 1980, when Zimbabwe achieved independence, could the new leaders finally affirm that the site was built by their own ancestors. During the 1960s, black nationalists had even settled on Zimbabwe as the name for the country they hoped to lead to freedom, harkening back to Great Zimbabwe.

Since 1980, local archaeological research has been slow to resume and has dealt largely with maintenance and repair. Research has instead focused on the satellite sites, in part because they were less disturbed by early excavations. Manyanga emphasised that scholarly understanding of Great Zimbabwe has shifted. "Eurocentric models interpreted the site as though you were looking at a castle in Europe. What has come to light from recent work is that Great Zimbabwe was built over a long period of time; it was not built once and then occupied, but grew over time. Even the walling came at a later stage because earlier on there were farming communities at Great Zimbabwe."

Today, the great ancient city remains just as important for Zimbabweans. Shona villages are located nearby, and many residents work to maintain the site. A religious centre is close by too, and the site still attracts worshippers who practice traditional Shona faiths.

"It was Africans who created this," said writer Marangwanda. "And over a millennium later it's still standing. It's a testament to who we are."

BBC Travel's Lost Civilisations delves into little-known facts about past worlds, dispelling any false myths and narratives that have previously surrounded them.

431 notes

·

View notes

Text

And then when we can't think of how to start it, we create memes

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

That thistle in the foreground, next to the wash.

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Word of Advice About Critique Groups, Beta Readers, and Other Peer-Based Feedback on Your Writing

In my time as a professional editor, I've have many writers come to me with stories they've been trying to improve based on suggestions from critique groups, beta readers, or other non-professional feedback sources (friends, family, etc.). The writers are often frustrated because they don't agree with the feedback, they can't make sense of the comments they've gotten, or they've tried their best to implement the suggestions but now they've made a big mess of things and don't know where to go from here.

If this happens to you, you're not alone. Here's the deal.

Readers and beginning writers are great at sniffing out problems, but they can be terrible at recommending solutions. For that reason, critique groups can be a disastrous place for beginning writers to get advice.

Here's a good metaphor. Imagine you don’t know the first thing about cars. Someone tells you, “There’s oil leaking onto the driveway. You should cover the car with a giant garbage bag.” Alarmed, you oblige, only to be told the next day that “now the car smells like burning plastic and I can’t see out the windows.”

A mechanic would’ve listened to the critic’s complaint and come up with their own solution to the leaking oil, ignoring the amateur’s ridiculous idea, because they know how to fix cars and can use their skills to investigate symptoms and find the correct solution.

Critique groups actually aren’t bad places for experienced writers, because they can listen to the criticism, interpret it, and come up with their own remedies to the problems readers are complaining about. Beginning writers, on the other hand, can end up digging themselves into a deeper hole.

There's a great Neil Gaiman quote about this very conundrum:

Remember: when people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right. When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.

So what to do?

First, try to investigate the reader's complaint and come up with your own solution, instead of taking their solution to the problem. Sometimes, in the end, the reader's solution was exactly right, which is lovely, but don't count on it. Do your own detective work.

Second, take everything you hear with a huge grain of salt, and run the numbers. Are 9 out of 10 readers complaining about your rushed ending? It's probably worth investigating. Does nobody have an issue with your abrasive antagonist except your cozy mystery-loving uncle? Then you might not need to worry about it.

Third, give everything you hear a gut check. Does the criticism, while painful, ring true? Or does it seem really off-base to you? Let the feedback sit for a week or so while you chill out. You might find you're less sensitive and open to what's been said after a little more time has passed.

Lastly, consider getting professional feedback on your writing. Part of my job as an editor is to listen to previous feedback the writer has gotten, figure out whether the readers were tracking the scent of legitimate problems, and offer the writer more coherent solutions. Of course, some professional editors aren't very good at this, just like some non-professional readers are amazing at it, so hiring someone isn't a guarantee. But editors usually have more experience taking a look under the hood and giving writers sound mechanical advice about their work, rather than spouting ideas off the top of their head that only add to the writer's confusion.

Hope this helps!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

REVERSE TROPE WRITING PROMPTS

Too many beds

Accidentally kidnapping a mafia boss

Really nice guy who hates only you

Academic rivals except it’s two teachers who compete to have the best class

Divorce of convenience

Too much communication

True hate’s kiss (only kissing your enemy can break a curse)

Dating your enemy’s sibling

Lovers to enemies

Hate at first sight

Love triangle where the two love interests get together instead

Fake amnesia

Soulmates who are fated to kill each other

Strangers to enemies

Instead of fake dating, everyone is convinced that you aren’t actually dating

Too hot to cuddle

Love interest CEO is a himbo/bimbo who runs their company into the ground

Nursing home au

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ugh, was having a great time mocking my recently imprisoned rival when I noticed the camera positioning makes it so that I appear behind the bars, thus framing me as trapped in a metaphorical prison of the narrative, now my whole day is ruined. Fuck.

104K notes

·

View notes