Text

How This Ends

Loan Tran

Two weeks into quarantine I read an article in The Atlantic titled, “How the Pandemic Will End.” It still felt wildly early to make any predictions about the future and the course of the virus. It has been now over a year that I have been trying to write a response to what I read, not because of any substantial disagreement but I foresaw then what I know now to be true, that after nearly a year of pandemic life: none of this simply ends.

There are no numbers and statistics, CDC guidelines, or even well thought out epidemiological reports that captures the depth of what it means that over 2.75 million people have died from COVID-19; over half a million of them alone in the U.S. We have witnessed a year that has made everything that was terrible before, much, much worse. And we know how we got here—especially being in the belly of the beast— we know all too well what regimes of power are capable of in their commitment to greed and profit. If you are like me or if you love people like me, you may know too that the world has come to an end many times before. What is different about this ending? If anything?

It was mid-March. My partner and I were on our way to the beach for her birthday. During our drive, we got news that the airports were starting to shut down and we were uncertain of the rumors about the National Guard being deployed to ensure compliance with stay-at-home orders. The beach was still there, and still sweet as always. We celebrated her the way we love each other; we ate delicious food, we laughed. She made her family’s shrimp: Lee Adam’s Shrimp. Which is comical, she says, because this was the only dish he would ever cook, and he got it named after him. Meanwhile, the family functioned because of women who made everything else possible. Such is our lives.

The Atlantic Ocean on the coast of North Carolina in mid-March is wind-swept, vast, very quiet. The sand becomes these large mountains to be trekked over before the water meets your eyeline. But once you see it, you know exactly where the ocean departs the sky. It was terribly cold. Yet, I was grateful to be by the water as our world began to shake us into conference calls and organizing meetings. Within just a few short hours of our Governor declaring lock down, we had formed the United for Survival and Beyond coalition. And knowing the year we were going to have and coming out of years of pavement pounding work, we were already exhausted. Deeper than the exhaustion is the truth that we must stick together, and we must find a way to continue on, especially now, with the cards so clear on the table: some of us will live and some of us will die. And there will be no logic to the madness.

The political work is instinctual to me; it makes sense in any crisis to bring together as many people as possible to understand a situation and to then take action. But the political work is also sometimes slow moving, even when we are all speeding and incredibly busy. So, I did other work that I felt, by my own standards, was more tangible. Like organizing a group chat of the queers I know who need medication on a regular basis. Or joining the local Mutual Aid Groups (and then promptly leaving all of the groups, which was simply a matter of exiting the Signal threads). Making a phone tree that was unreasonably the size of a phone book itself was an early action, too. And of course, cooking. There have been gallons upon gallons of pho. And gumbo. And at least 1,000 meatballs. Anything to attempt at satiating what I knew would become a growing hunger inside of me for a normalcy that still has not yet returned.

Things were deteriorating quickly all around me. By March’s end, my mom and I are on hold with her retirement company. She wants to get her money out of her account before the stock market steals it all away. This economic system routinely comes tumbling down for her; and often does it too line the pockets of the already ultra-wealthy. She has earned her retirement from working at the same alterations shop for over 20 years. She is paid for the time it takes to hand sew sequins onto wedding gowns that cost more than her year’s entire salary. She makes the inseam of your boutique jeans go from 32” to 30” with you never knowing the difference. She helps make people feel good, never questioning their own frivolousness in paying someone else to replace a missing button on their jacket. Her job has treated her well. This pandemic was beginning to test it as she’s filed for unemployment, without assistance from her bosses. The alliances that had shaped her life up until this point were beginning to fall apart, as is the case for so many of us.

It would become easier in the summer, but even then, the sweaty walks and the sitting outside in the beating sun just to eat a meal with someone who I wasn’t also sleeping with most nights began to tire me. I was unsatisfiable. I am lucky to have eaten many good meals, celebrate even more pandemic birthdays, and have extra money to keep supporting my parents’ and sister’s bills in between our socially distanced visits. Things would seem relatively calm for some weeks, when I felt like the weather wasn’t badgering on me. Which is to also say, that when things felt turbulent, it really just meant I was incredibly sad.

As I’ve been writing this piece in my mind, mulling over—as I usually do—which details feel relevant enough to evidence in words, the world around us has danced to the precipice of something new and back again. In between it all, I have had some of the most elaborate dreams of my life, the dreams at the heart of how I wish life could be.

I am home in Viet Nam. The sky is a dreamy pink, small stripes of orange and some residual blue as the sun sets and the moon takes over. I am sitting by the water and before me stretches a few miles of the bay. On the other side, mountains: spotted gray from granite and green from trees. I think to myself, “this is beautiful” and I take out my phone so I don’t forget what this looks like. My mom is here with me and it is quiet and perfect. Standing in line waiting to buy coffee from a street vendor, I think to myself, “wow, I get to be here,”; there are children and their parents who look my kin weaving around my stillness on the side of the road. I smile at someone I clock to be like me: a little odd, short haired, sweet looking in the face, stern and tough but kind in spirit. Then I wake up. It’s a dream. And all I know is that it’s a beautiful, perfect dream.

While time stretched and I could dream and I could travel in my mind, buoyed by my memories, telling stories that after the 3rd or 4th re-telling feels almost untrue, time also pulled me back to reality. To the everyday where I had few answers for the big question of: what now?

So what of time now? What is its worth? And what is worth it? I wear a watch every day still and I check my calendar still. And I still want Fridays to feel how Fridays are supposed to feel, still: they should release me. I still want to wake up slow on a Sunday, my favorite day, still. Things feel numbered and open all at once. Do I measure the worth of my life in this way or that? Do I consider tragedy to be where we start or is it having a witness to it that makes the clock run? Do I count the pints of soup I have made? What about the distance between us? There have been more cardinals than usual, but I’m really not counting. I do miss the children in the streets and the laughter beaming from their hands. Making sense of quiet and calling this place, my ever-growing city of just nearly 270,000 people, a ghost town seems a little defeatist; some days it seems just right, and some days it feels like an opening: to stop counting the time.

There is a slowness of this period that I have come to appreciate, even as it frustrates me. The slowness to remember and reconsider and re-learn the basic unit of relating: care; to care for each other and to care for ourselves. And we are being subject to the realities of care’s absence: there are millions of people—while they toil and make our world turn, even against the heaviest measures of despair—are disregarded as undeserving of housing, of health(care), of food, of life itself.

These systems of violence and domination continue to evolve, as showcased by this next phase of neoliberalism, with its elite colors and sloganeering. Coca-Cola racial justice investments and Nike’s you can do it to end racism and NFL’s $250,000,000 check to shut it (what, exactly?) down. Our task is more urgent than ever, yet there is still, simply this: you and I making a road where perhaps previously there was not, where perhaps previously there were, and it had been bombed or torn apart.

I am on the eve of my second pandemic birthday. And between the last time I dared contemplate how this ends and this moment now, there have been attempted coups and multiple mass shootings; there have been more vaccines distributed in the 1st world and essentially none for our sisters, brothers, and kin to the global south. Schools in my city are reopening and the people who suffer are made to blame each other.

A pandemic of this kind, through which a virus has served as the vehicle sounding the sirens of human plight, has the potential to lure us towards conclusions about the ever-deepening crises of white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism that will be regretful for us in the long-term. Namely, while it is true many things are outside of our control, like how a virus may mutate or transmit, there is so much more that is within our control.

We have witnessed that even in the middle of a pandemic, our people have risen up across the globe to declare that there must be another way to live. What deserves to be said again and again is that on one hand there is the science of this pandemic and the science of greed which profits on sickness; on the other is clear the science of solidarity; the science of organizing; the science of returning people back to each other; a sense of attention, a regard for care, an interest in ourselves and each other and the planet as people and places worthy of a world different than what centuries of violence and domination have conditioned and forced us toward.

At last, I do not know what the end of this pandemic means. But it seems to the hopeful, revolutionary optimist in me, that we have tried our raggedy best this year. I have appreciated more than ever our attempts at an honesty we may not have been willing to demonstrate. It seems to me that I haven’t been the only one to lie about how much I don’t know. And if you are looking for a script right now, about how to be, or how to cope, or how to regard yourself as belonging to those around you who do not look like you or speak like you or understand as you understand, I hope you’ll remember that there is no one else to make the future but us if we are to see ourselves in it.

I am embarrassed by my desperate need for things to return to normal. I am so desperate that I lay awake at night: wanting something I know I cannot have and the intelligent part of me knows that if I could have it, it would not be good for me or the people I love. The desperation is also a grief, fear, fatigue. But I also lay awake some nights taking audit of my gratitude; that beside me is my lover deep in restful sleep, that somehow in the morning our hands always find each other; and when we get out of bed, to make breakfast, or step outside: there is another day that affords me the time to learn how to be more human, and perhaps that is what this is worth. And those of us who still have it in us, and even those of us who feel that we have lost it, we must help this situation by becoming more and more human, as that is the only way I would want this to end.

This piece is dedicated to my dear friends who have kept me this year, in particular Zaina, Mindy, Margo, and Nadeen. It is also dedicated to our beloved Elandria (E) Williams, may they continue to rest in piece and know that we are taking their mandate for us to care, seriously. It is dedicated to the best pandemic pal and partner I could have ever asked for, who has also vowed to return the favor next pandemic, Chantelle. This is dedicated to the streets, to the uprisings, to all people everywhere who believe life doesn’t have to be this way, that we are so much more—these people include city workers, educators, youth and students, organizers, healthcare workers, and more. Thanks for the example of your lives.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

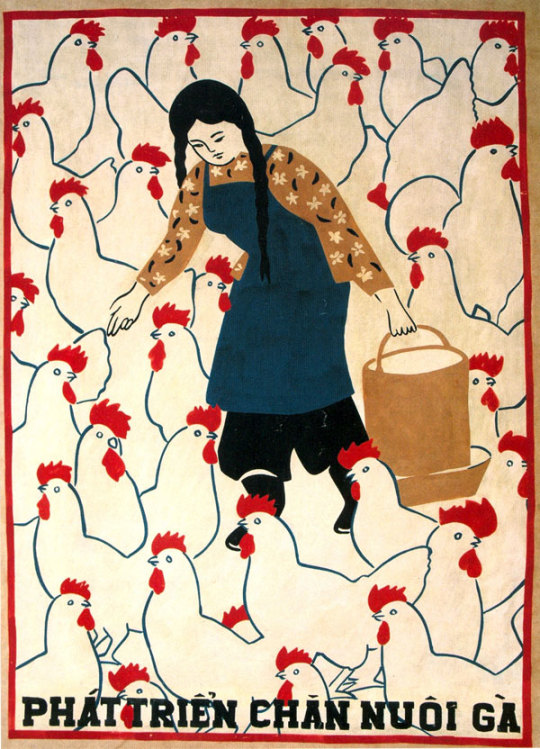

To be women

loan tran

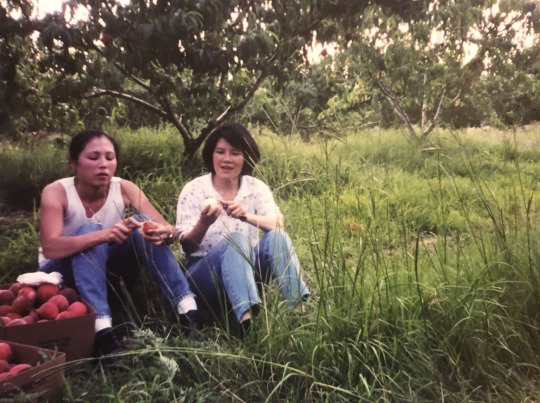

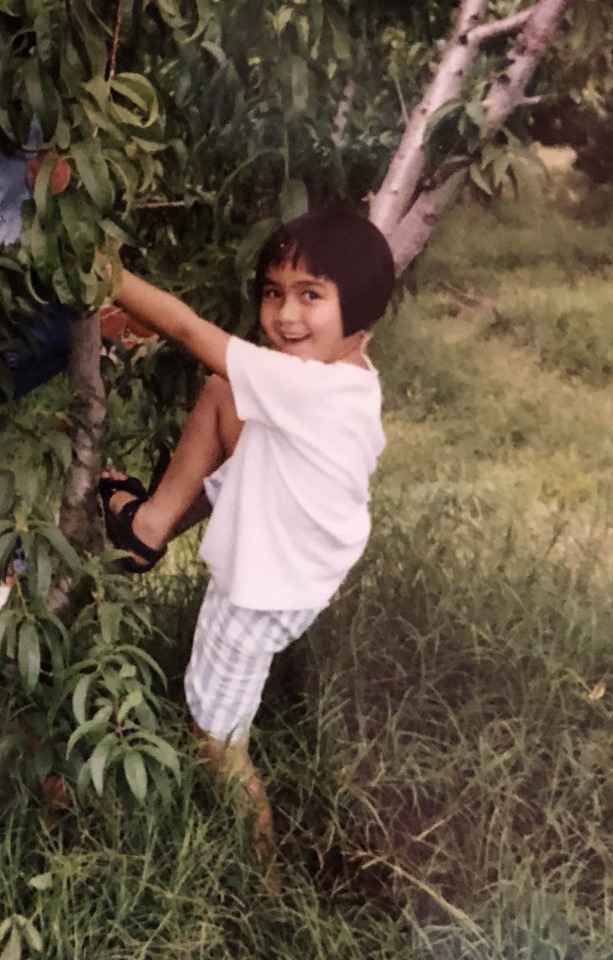

I am 6 years old. My hair is cut into a short bob and I am wearing a white t shirt and striped shorts in a peach orchard. I lean back and smile at the camera before climbing the tree with my leather strapped sandals. The women all around me are laughing under the shade with small peeling knives in their hands; separating skin from fruit. For a moment their hands are soft, peach fuzz smoothing at their callouses from days and years of piecing together fabric at their sewing machines. They enjoy each other. I reach for my own peaches and later I stand in the back of my family’s green pick-up truck waiting for someone to weigh our baskets filled to the brim. I hold my hands behind my back, small and shy, watching a woman shift and re-arrange the crates. I am awkward and can’t stop staring. She only smiles back at me.

I am 8 and spend most of my days after school with my dad at the billiards hall where he plays cards and jokes in the backroom with his friends. I make my own friends with the domino sets, the wobbly coffee tables, and the woman who works there. She has long black hair, just like mine, though kept much better. One afternoon she tucks me gently into her arms as we sit on the hood of an old Cadillac. Everything bright: the car, her pants, her smile. I am small and still shy, hair longer, and with the reasonable fashion sense of an 8-year-old; pink leggings sticking out from under my khaki uniform pants, matching my pink shirt. I am wearing sneakers and she, a pair of black stilettos. She cares for me in absence of everyone else and I never feel like a burden.

I am lucky that from a young age, the women around me, if I paid enough attention, allowed me a life to claim, to call my own. They offered a recognition that I mean something. I’ve learned that women make a conscious choice to love—not in a reductive way; not in the, we are ok extracting feminized labor kind of way. But in a way where time and time again, I have seen the women in my life deprived of respect in a world hellbent on their punishment for not being man, or white, or able-bodied, or straight, or cisgender still root in dignity and regard for other human beings. I am lucky for the persistence and clarity of women’s regard.

“Woman”—with its complexities, contradictions, and its constant dance against/with/for colonization, white supremacy, patriarchy and transphobia, and capitalism—is not a matter of biology. It’s instead the active choosing of the relationships, connections, desires, acts of care and love we are trained to cast away and make invisible.

Women’s regard is what makes me the dyke gender non-conforming person I am. It is what gives me the conviction to be on testosterone and feel confident that I can be a woman of a different kind.

The women who make me woman are the women who clearly have defied all odds to be their own, in a terrifying and heart wrenching world which takes from them everything: their bodies, their joy, their love, and their care. The ones who have been called failed women, because of their skin, desire, shape and size of their body, or ability of their body. The ones who have strapped guns to their backs to harvest the field and have written poems at wartime; whose strongest political directive, whose clearest tactical skill comes from a place of deep knowing that the care we have for each other allows care for ourselves, and that is what gives everything in this fleeting lifetime meaning.

To be women, in the morning:

I wake up and question the width of my own hips or contest the shape of my chest, wondering if it is meant to look this way. I wonder where else this body could have hair and why don’t I have it there. I argue with myself in the mirror; on today’s menu of misogyny, do I want to be seen first as a man and then a woman or a be seen first as a woman and then a man? I try to accept that when I leave the mirror, my want won’t matter. I clean my skin with an alcohol pad and inject testosterone into my body. This is one year and not much has changed. I cringe at being called “sir” for my voice and mustache as much as I cringe at being called “ma’am” for my hips and breasts. I am anxious that what I believe lovers love about me is different than what they may actually love about me. I am worried about love. I wait still for the moment of “discovery”; for when someone claims I have lied about myself and that somehow that is more offensive than lying to myself to comfort them. I get good at redirecting the self-negating thoughts. This body hollows out on command when I am misnamed. I get ready.

And in the same morning:

I wake up and feel desire and heat in my bones for a woman. I imagine the skin of my arm touching my face to be the skin of another woman. I find tenderness with a certain name I can press my tongue into, so softly, without hesitation, as if that name were my own. I smile to myself imagining the full depth and gravity of the lives of the women around me. I read these women. Adrienne Rich writes: without tenderness, we are in hell. And Toni Morrison said: It is more interesting, more complicated, more intellectually demanding and more morally demanding to love somebody, to take care of somebody, to make one other person feel good. And my body eases in the middle of a world on fire. I remember to keep caring, to smooth the callouses, to enjoy the fruit. I get back to the ground, to the earth, to my own body that women make possible; whether with piss your pants laughter, unashamed crying in public, or the caring nudge of a plate of food in my face: eat, you have to eat. So then I look in the mirror at myself and think: oh, there she is. There’s the woman I’ve been looking for. There’s the woman I am choosing to be.

The most significant relationships in my life have been with (other) women, somewhere on their journey – whether across borders, lifetimes, bodies, or binaries. We bear a kind of witness for each other that tells me that I can’t separate my gender and my desires. Who I am is who I want is who I want to be. No more flattening, no more making the parameters of this life small, the possibility of this life small—when our lives deserve to be big, complex, ever-changing, bursting at the seams with the invitation to constantly become what we are seeking of and in each other.

For a long time I have seen this body as nothing more than a failed project. This body: Viet, survivor, migrant, gay, gender non-conforming, girl, weirdo, woman, freak. I learned early that my body would not be my own unless I fight for it. I have been fighting for it for a very long time. And I love it just a little better now, having given myself permission to belong to this body and to remember womanhood is something ever expansive.

I choose woman for myself because I want to honor my own pain and misery and heartache and joy and pleasure; because I want to be like those women in my life who have a steady generosity to stand witness for the pain and misery and heartache and joy and pleasure of others—as friends, family, and lovers.

I am 10 years old and the only way I am speaking to the world is through a composition notebook drowning with badly written and very sad poems. My dad has gone to jail and I feel utterly alone. In my yearbook, my English teacher, Mrs. Roberts wrote: keep writing, you’re good at it. So, this is for me, for the women to whom I owe my life and belonging. For the women who have given me the chance to choose and to be. And to be of them.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am writing to you from the 51st anniversary of the My Lai massacre that took place during the American war on Viet Nam. It was a brutal slaughtering of at least 500 people, women, children, and men in a small village on the claim that there were active Viet Cong (communist) or VC sympathizers in a neighboring village. That March of 1968, the Charlie Company of the Americal Division’s 11th Infantry Brigade, led by Lt. William Calley, raped, mutilated, and opened fire on the My Lai village. No Viet Cong. Only a few weapons. This was covered up for nearly two years before a soldier in the 11th Brigade broke rank.

This piece of my people’s history alone is enough for me to be born with every bone in my body refusing the U.S. declaration of freedom of democracy. This refusal is not only historical, it is current. I cannot be a person of this experience and believe that U.S. intervention in Venezuela is in the service of the Venezuelan people; that U.S. intervention and occupation anywhere (and the list, past, current, and either directly or through proxy, is very long: Libya, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Colombia, Palestine, Korea, Guatemala, Philippines, Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia, Cuba, Brazil…) is never in the interest of oppressed people, working people, poor people.

I do not claim any authority on what it means to be of Viet diaspora, or to belong to the many generations of people from many different nations who have had to flee or escape or cross oceans to breathe easier. The pain is very deep, it has traveled very far, to nearly every inch of this planet. It is confusing, it makes life difficult. It complicates political work on the basis of individual experience and not on the basis of collective imperative to change the violence which confuses us.

But I do claim authority on being a product of history, which is not as simple and one sided as so many of us are led to believe.

I know that most people coming up in the U.S. in the decades following the American war have read at least 2 paragraphs about the project of “U.S. democracy” in Southeast Asia. Simultaneously, they, me, all of us, have also read and eaten up the thinly veiled anti-communist and racist propaganda accompanying this vision. We’ve seen time and time again how powerful it is when capitalists, colonizers, and imperialists get to write history.

Do we really think a place like this has the interest of oppressed people in mind, ever? How could any colonial and imperialist organ such as NATO and the Pentagon have the right to give voice to democracy or justice? Have our individual pains twisted us up so badly that we have forgotten this is an empire we are talking about? Words mean things.

While writing this I had to Google “My Lai Massacre” several times, for fear that I would get the year wrong (1968) or that I would get the number of people slaughtered wrong (more than 500, at least) or in some twisted way, I would get the place wrong (My Lai village in Quang Ngai). To be frank with you, being of diaspora in this particular empire, during this particular moment, it is hard for me to recall any details of anything I have ever learned — about myself, about my people, about any people, really, subjected to the violence and vicious greed of war-mongering, colonial, and capitalist vultures. It’s truly a mind fuck. That is the point of empire, to make us crazy in every possible and every which way.

Part of this crazy making are the clever ways empire is able to isolate us, make us feel as if our pain is the only of its kind; that — especially for those of us living in the U.S. — it is separate and divorced from the pain experienced by those around the world. There are many of us pained. I don’t have exact numbers, but my vehement opposition to capitalism gives me enough confidence to say the number is probably about 7 billion, give or take the rich and the soulless (different and the same).

I believe there is also the crazy making of arrogance that sometimes we use to deal with our pain. We see this a lot and we struggle with it in large because we experience some relative pleasures and luxuries of organizing in the belly of the beast. State repression and police retaliation are still very real, I’m not saying our people aren’t targeted for offering political and tactical leadership. But there are some nuances here we should really strive to sit with if we call ourselves anti-imperialists and internationalists. And these nuances can only strengthen us, it contextualizes every struggle as a global struggle; it mandates that we all take our work and our futures seriously; it demands of us a rigor that is not just in word or thought, but in action.

The left (lol) in the U.S. is fractured, it is damaged, it is traumatized. It really doesn’t have its shit together and we know everyone is busting ass to make sense of a situation that is almost incomprehensible in its scale and monstrosity. In our best moments, we are relentless and resilient and so capable. In our worst moments we are burn out, exhausted, and even harmful to and for each other. I don’t really know what to do about or with this.

I’ve been thinking about war and I’ve been obsessed with pain and loneliness because I am human and maybe because the only way I’ve been able to deal with a great feeling of hopelessness is to dive into the things that terrify me the most.

There’s a cliche about being born alone and dying alone. I think it’s an extremely individualistic and selfish way to look at the world. We are seeped in a culture of vapid individualism; it’s very cruel that we hurt ourselves while being hurt. It makes me very sad but I get where it comes from. It comes from same mouth that says it’s totally reasonable that Jeff Bezos is a billionaire while Amazon workers pee in water bottles at work; the same mouth that contorts itself to convince us that it makes sense there are enough empty houses across this country to house every unhoused person and then more; the same mouth that twists and turns red lying about how one of the wealthiest countries in the world cannot afford to provide healthcare to all of its people; the same mouth that propagandizes about the redemptive nature of prisons when it is not Black people, indigenous people, immigrants, queer and trans people, disabled people or poor people who need to be redeemed; and of course the same mouth that says it’s possible for Juan Guaido to be the interim president of Venezuela while Donald Trump is the president of the U.S.

Perhaps the logistics of birth and death are singular, but after we are born, we live and before we die, we have lived a life that is wild, at times tumultuous; filled with mistakes, questionable decisions, bad, bad, bad decisions; but a life, for so many of us, all the more beautiful, interesting, worthy of something, because we chose to not be alone in our sorrow or alone in our struggle for liberation.

I will always choose to reach past the isolation, the crazy making, the arrogance, and the pain of it all — for something beyond, something so much bigger than all of us; something I know all of us deserve.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calling In, Take 2: Power, Accountability, Movement, and the State

In the winter of 2013, I wrote a piece titled, “Calling IN: A Less Disposable Way of Holding Each Other Accountable.” Over the next four years or so, this piece would become the bane of my existence. Let me explain.

This piece sort of exploded – I was receiving emails and messages that the piece was really resonating with folks doing justice work across all types of communities. It was true and probably is still true how tired we all are of the constant worry that we cannot make mistakes – not even among those who we call friends, family, and/or comrades.

There have been numerous challenges that have arisen since the publication of this piece. The first is that it was so wildly appropriated by white people to rationalize or justify their own racist behavior. It’s been wildly appropriated to push away valid critique of racist or otherwise oppressive behavior. I remember as Ani DiFranco was being called out for playing music at a slave plantation, that white lesbians were quoting “Calling In” to tell Black women and women of color that they shouldn’t be critiquing Ani (or other white people) in such a harsh way. I don’t think I need to offer any more examples on how this piece or this concept has been misconstrued to mean, “I can do whatever I want and you have to be nice to me.”

The second challenge actually has a lot more to do with my own political development than external factors—how it was being read by my community or how it was being used by those inside and outside of my community. In the four years since writing this piece, I regret to some extent not writing more about the relationship we have to each other in movement versus our relationship to each other and that relationship to the state – the apparatus which seeks to and often succeeds at dividing, repressing, and conquering (literally and metaphorically) us.

I have become regularly frustrated by some of the contexts in which “calling in” has been used or named. It’s less about people annoying me (because people annoy me a lot) or some idea that I am the arbitrator of what “calling in” as an accountability practice or process actually means. It is actually more about the individualistic ways we think of accountability, power, and our relationships to each other. In many ways it is not surprising that we conceptualize ourselves as simply individuals. We are born into this world by ourselves (unless we’re a twin or a triplet, or something, but you get my point), we experience much of the world with only ourselves (even if many of our experiences involve others), at night we fall asleep and wander into the dream world on our own, and when we die – and we all die – we die alone.

We take the reality of the human experience as being both terrifyingly and rewardingly lonely and compound it with the deadliest economic, political, and social system in existence, capitalism, and most of us end up having a lot of shit to unpack around our individualism, and specific to this context, our understanding of harm and repair.

So what does it mean to hold each other accountable in a world that is incredibly messy? In a world where we don’t have much to rely on but the reality that things are incredibly messiness? That isn’t to say that there aren’t topics or issues where we are capable of drawing a clear line. We know how to do that – that’s why we have vibrant social movements.

But we have to start figuring out the space that exists between ourselves and our communities, our communities and the movement, and the movement and the state. Not only do we have to start figuring out that space, we have to do this in a way that is honest, transformative, and real.

I don’t think that I can say this enough: we are human beings and we have our shit. We carry with us the traumas we experience from early ages, that we don’t start developing different coping mechanisms for until later in life. For some of us, it is much later in life or it is never actually dealt with at all.

Being in movement has taught me that movement brings together the maladjusted weirdos of society who have decided or have been led to doing something about their own and others’ maladjustment. When I say “maladjusted” I am capturing a pretty broad stroke of people who are, by the standards of this system and society, not fit to be a part of this system and society. We are rightfully upset, uncomfortable, and angry. In most aspects of our lives – at our jobs, in our classrooms, in our neighborhoods, and most public spaces, including those that are allegedly democratically elected to represent us, we do not belong nor do we have power.

Movement is where we have power. Movement is where those of us who have seen the most fucked up shit; have made a whole lot out of the nothing slapped to us by capitalism; have had to endure the incredulous crimes against humanity, whether it be gentrification or police brutality, homelessness or addiction, incarceration or unemployment; have once believed that we might not survive another day have managed to find others, to find a way, and to fight for our right to life every day.

The power we have in movement spaces is beautiful, transformative, and sometimes (and increasingly so) threatening to those who have power over us. But the power we have can sometimes fuck us up. Let’s be real. Sometimes we get power and suddenly no one is a friend, it’s only foes. And it’s especially foes if not everyone agrees with us. Sometimes we get power and we become stagnant, we start operating in the interest of preserving our own power, instead of remembering why people’s power means anything to begin with: we have to build with other people to win. Our fingers tight as a fist are much stronger than they are a part. Our arms linked are a much stronger barricade than our shoulders alone in the cold. The harmony of many voices is much louder than just one.

The movement gives us power and we start acting like calling out greedy politicians and corporate profiteers or politicians who want to rid the world of queer and trans people is the same as calling out our cousin who makes sexist jokes at the family reunion or even a fellow organizer who takes up a lot of space as a white person. These are fundamentally different relationships. Our relationships to capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy as pillars holding up a destructive and deadly system is fundamentally different than our relationships to the human beings who have to survive these systems.

The state is an oppressive force that seeks to cultivate division and thrives on our disconnection and alienation from each other. Let’s try our best to not feed it with our harms and grievances as if it could help us resolve them.

Our movement is, in many ways, fighting to confront the state. We are disrupting the institutions and systems harming our people. Our movement is not mechanized with an oppressive ideology; we are not weaponizing ourselves toward profit; we are not propping up fake democracy to make the rich more comfortable; we are not fighting to dispose of our people, leave our people behind or for dead. If we are truly building our movement to confront the state, we’ve got to stop treating each other like the mistakes we commit are the same heinous crimes that the state commits against our people. We are all capable of causing harm but we can’t operate as if the harm we cause to each other is the same as what we experience from the state. Often, the harm we cause to each other happens in the process of trying to build a different world.

Somewhere along the lines, the idea of “calling in” was put in opposition to “calling out.” I don’t believe that such dichotomy exists, since I think that our accountability should be more rooted in our understanding of power, to each other and to the forces that seek to exert power over us, than rooted in our individualism and selfishness about who gets to be right and who is wrong.

But ultimately, whether you want to call in or call out, let’s all try to be on the same page about who our shared enemy is – and it is not each other. I stick by a lot of what I originally wrote in that piece in 2013. Movement building is about relationship building. And it’s also about nuance. In the piece I elaborated on how we use our relationships as the basis for determining whether we "call in" or "call out." I’m still less interested in how we label our processes for holding each other accountable and more interested in the process itself. Some questions that I would pose to folks when they are deciding how they want to deal with an oppressive situation are: what is the depth of the relationship I have with this person? Are they someone I consider an acquaintance? A friend? A comrade? What values do we share (if any) and what are they?

There are deeper political questions that should inform how to hold people accountable, too -- because everything is political and more importantly, because everything requires us to think of ourselves within the context of a broader society. Our society necessitates harm in order to thrive and it can either continue to thrive or be delegitimized based on our responses to harm.

We live in a real society of disposability. We talk about it a lot but I think sometimes we forget how entrenched we are in it. When we talk about the prison industrial complex, we are talking about a world that puts people in cages for the rest of their lives because of an accountability system where the state arbitrates who gets to make mistakes and who doesn't. The structural violence carried out by the state shapes and informs how we relate to each other interpersonally.

Lately I’ve been returning to the fact that we are human beings. This kind of statement is obviously a little oversimplifying. We are human beings who are greedy, selfish, cruel, unforgiving, vengeful and also deeply feeling, compassionate, remorseful, creative, apologetic, loving, and caring. Some of the human beings on this earth commit viler nastiness than just being human – we know that this shows up in our communities and in the broader world as sexual, emotional, and physical violence, all tied and connected to capitalist exploitation and oppression: white supremacy and anti-blackness, transmisogyny and homophobia, islamophobia and xenophobia, Zionism and anti-Semitism and more.

I'm not saying that there is never harm nor that we should martyrize ourselves to minimize the harm we experience. I'm saying we should remember we have all caused harm, have the propensity to cause harm and if causing harm or making mistakes were the basis for whether or not we maintain community with each other instead of our humanity, our dignity, our aptitude for change, and our belief in a radically different and better world, we'd have no community. And probably just as scary, if not more, we’d have no movement.

There is no perfect way to deal with harm or conflict. We are trying our best to maintain our relationship to each other and ourselves in a world that is routinely dehumanizing, under a system that doesn’t care about what we mean to each other. But we should care about what we mean to each other.

As a queer and gender non-conforming person of color, a migrant from Viet Nam, and a communist, what keeps me alive is the fact that everything changes – that in fact, everything must change. When something has stopped changing, it’s dead. If there’s nothing that is useful from this piece, any of my (largely unoriginal) musings on power, accountability, movement, and the state – I hope at least that we can all remember and respect that everything changes. That this be a gift we do not take for granted, that this be a gift we give to each other in service of a better world, a world where not only are we capable of transforming but one that our transformation made possible.

In the spirit of change, I acknowledge that four years from now I might write a totally different piece, depending on where the forces of this gruesome planet are, depending on the tenacity and resilience of humanity, I might write a take three. But for now, I hope that I’ve done some justice to those who I am fighting alongside with each and every day, whose mistakes I share in, whose vision I believe in and co-create, whose wisdom, commitment, and revolutionary optimism reminds me that healing, being free, and almost anything is possible.

75 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I was never certain

who I was supposed

to be here.

Jen Rouse, from “Audience,” Acid and Tender (via lifeinpoetry)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Please—

what’s the word for being born of sorrow

that isn’t yours? For having a family?

For belonging nowhere? Not even

your body. Especially not there.

— Cam Awkward-Rich, from “Another Middle-Class Black Kid Tries To Name It,” published in Nepantla

600 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Less by Alice B. Fogel

It was twilight all day.

Sometimes the smallest things weigh us down,

small stones that we can't help

admiring and palming.

Look at the tiny way

this lighter vein got inside.

Look at the heavy gray dome of its sky.

This is no immutable world.

We know less than its atoms, rushing through.

Light, light. Light as air, to them,

for all we know. Trust me on this one,

there is happiness at stake.

Boulder, grain. Planet, dust:

What fills the stones fills us.

I remember, or I have a feeling,

I could be living somewhere with you,

weighted down the way we aren't now.

Often the greatest things,

those you'd think would be the heaviest,

are the very ones that float.

0 notes

Text

SOMEBODY WHO LOVES ME

(in honor of the 1 year anniversary of the shooting at Pulse night club)

at the local gay bar

you see close like

fingers hooked through belt loops

a hanging on

where the dance floor sits still

catching our knees in each beat

in a room low and tight

fearless is thinking of dying

casual like our belief in ghosts

how they sway with us in dance

wade in sweat, in bodies’ odors

like love

we tug the other to let go of death

our family sings out

to whitney houston

i wanna dance with somebody

we feel the heat of the world

outside rise from leftover tears

with arms spinning under the disco ball

our eyes glitter kaleidoscopic

we claim the most dangerous storm

the end is near

the favorite part of lines rehearsed

escape from our feet, bellow into the air

echoes of voice linger beautiful on their own

heartbreaking together

in synchronicity

moments we share

leave us alive before departure

don’t you wanna dance

with me baby?

my gut is how I know:

the last song that played is a space unchanged

where our kindred made ritual

through touch my hand sure in your palm

your head safe in my neck

our bodies a key for unlocking every door

we made a world where in nighttime

pulse is refuge

where only our hearts could kill us

we have survived you our acts of joy

our somebody when the music stops

we keep dancing.

0 notes

Quote

My parents have been married for over 30 years and I have been raised in their love. My mother told me my father used to send her a handwritten love letter every day when they were young in Somalia and sometimes twice a day when he missed her something bad. Love is having babies and fleeing a country in war together. It is being scared and being brave anyway. It is missing each other and always being friends. My parent’s love taught me that you need more than beautiful words for love to survive. Love is hard work, it is a commitment every day, it is doing what is necessary to make sure the other person is ok. My father somehow took care of a family of 12+ on a taxi cab driver’s salary and studied by a lamp’s light every night. My mother raised 10 children in a country hostile to their very existence with nothing but pure wit and strength. So I learned early on that love must manifest in actions. My favorite memory of them is how my mother would wait to eat until my father came home every day and them sitting together just laughing, talking, and loving. One time, my father took my mother’s hand and looked at us sitting around the table and told us, ‘you know, I love this woman. She is my best friend.’ And the way my mother still looks at my father, I know he’s not the only one who feels that way.

Yasmin Mohamed Yonis, in an interview for the Black Love Project (via ethiopienne)

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

march 7th 1957 lể kỷ niệm hai bà trưng

vintage photo of a holiday parade celebrating the trưng sisters who led resistance against chinese occupation in việt nam

1 note

·

View note

Text

I REMEMBER, DO NOT THINK THAT I FORGOT

4 notes

·

View notes

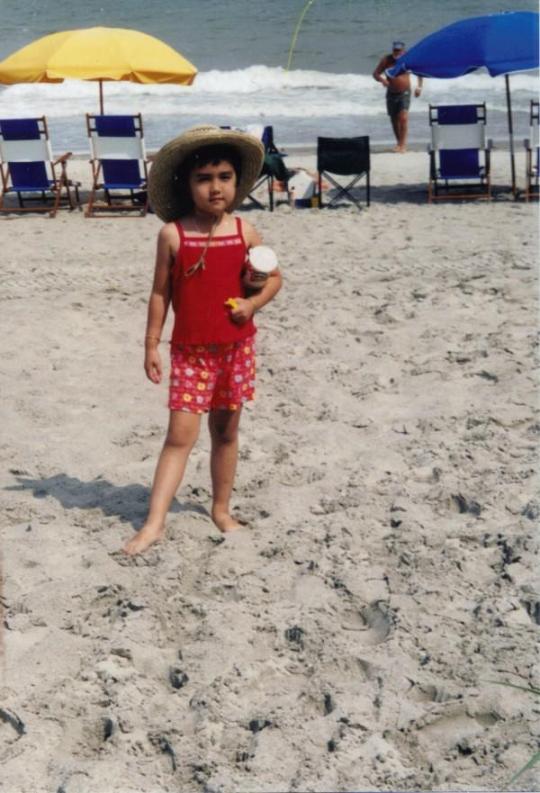

Photo

color coordinated commie calling

pringles picking pinky swears

beach body burying toes

old orange...oranges

aka

redlined, redstriped, redstarred yellow gurls

aspiring american red mostly white and blue

family dollar shorts and tan lines

white men who photobomb all the damn time

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[photo description: two bats hanging upside down. they are looking at the camera as one wraps one of its wings around the other.]

these are too cute i'm going to die

140K notes

·

View notes

Photo

"you eat this shit?" & the science of stomaching racism

middle school came and we were making ice cream in class, shaking sandwich bags full of salt and crushed ice. each period passed with another group of bright eyed 12 year olds scooping out cold, pasty white stuff on their finger tips, bragging about eating ice cream in class until there was nothing left to brag about and no one to brag to.

i liked the shaking more than i like the science. my biology class made it routine to want to eat the things we made, excavated and picked at from shoestring thin teacher budget ingredients. pop rocks and soda, cookies and chocolate chips.

one year we made agar plates for studying bacteria. and that year i was alone about wanting to eat the things we made.

i grew up with agar agar powder being a household, staple item. 49 cents a packet from the local super market and my mom could make 2 big phở-sized bowls of rau câu which was really just sweetened clear jello. sometimes she would brew a big batch of cà phê sữa đá and make a layered jello of coffee and coconut milk. a genius, my mom.

when rau câu settles and cools, the top layer is always a little tougher, it was smooth to the touch and was fun to save for last.

so when we made agar plates that one year and i said, "this is actually really delicious," they asked me, "you eat this shit?" and this fun science experience turned into silence; the pouring of hot water, the mixing of powder turned into still, hidden hands as if they could see all of the times i've peeked over kitchen counters with my tiny, greedy, chubby fingertips waiting to hold jello in my hands; what was commonplace in my fridge, at parties and after school for snacking became petri dishes only fit for bacteria and mold, distant and microscopic.

they won't tell you science is racist but they will ask, "you eat this shit?" and make your body and your mother and your people feel primitive, fitting enough to be distant and microscopic; exotic, foreign, alien enough to be poured and mixed, probed and left alone to harbor and harbor nastiness.

science will make you shrink and i trust no one who's never been delegitimized by it.

"you eat this shit?" so i swallow my tongue and say, "maybe i'm mistaking it for something else." and they all laugh that laugh that they do - when it's not really funny but a little more discomforting, awkward, questionable. i smile along, move my eyes away from the plate, dust powder off my hands: removing evidence that i knew agar agar to be anything but the filling for petri dishes ready to hold bacteria for science.

i wonder had it been different if i chose a different word. if i had said, "my mom makes this jello" instead of "my mom makes this agar." i wonder if that would've made them trust me over science, believe me over directions. even now, today, searching for photos of rau câu i tried to find more appetizing ones.

of all of the ways i have been taught in my science classes to think about my body, my gender, my sex, my race, my heritage: this memory of being silenced by science, being pushed aside for the validity of some discipline dominated by white bodies for the purpose of white bodies sticks with me the strongest - not because of the question those kids ask but because of the disgust and discomfort on their faces that follow my gut everywhere, fighting still to make itself more room than the delight and joy that rau câu and agar agar brings to it.

science does not sit well in my stomach yet it follows me everywhere. and i have cooled and settled too, my surface a little tougher and i save it for last to be broken.

481 notes

·

View notes