Text

Blog Post 10: Endless self-tracking & self-surveillance (Soon Poh Suan)

In Crawford’s Our metrics, ourselves: A Hundred years of self-tracking from the weight scale to the wrist wearable device, Crawford explored the historical account of the weight scale, by looking at its changing role as it shifted locations from offices to streets and to homes. This symbolized the normalization of technology and internalization of self-surveillance. Next, Crawford also analyzed the advertising campaigns of both weight scales and wearable devices and realized the association of self-knowledge and better lives connected to these external measurement of data. It is often to see advertisements emphasizing on the relationship between numerical accuracy, truth and self-knowledge; with better data, the better quality of self-knowledge and so a ‘better human’ is created. The sense of empowerment and control promised by these wearable devices or technologies of self-measurement reflected constant monitoring, self-surveillance and power over one’s body. With that, Crawford also used a case study of FitBit in courts to explore how wearable devices have advanced its role as a legal witness. These historical, semiotic and legal perspectives gave a comprehensive understanding of the tensions for a person’s desire for self-knowledge and the loss of privacy or control over the data.

With that, I strongly resonated with his perspective that the full use of these data is always out of sight to the user. Given the sense of discomfort and uncertainty that human bodies were being tracked, documented and rendered meaningfully through a device that records a wealth of data for the parent company, users have lost the agency to control the number of third parties gaining access to the data. For instance, the controversial use of contact tracing application, TraceTogether, in assisting the police force to investigate serious crimes have faced immense public backlashes for extending these TraceTogether data beyond contact tracing purposes. Furthermore, while these wearable devices promise to give the user a better self and better life through a mediated self-knowledge, I found these promises relatively disturbing as it normalizes the use of technology and capitalizes economic values on people’s curiosity to track the conditions of their own body. For instance, the Healthy365 smartphone application is an example of gamification and wearable devices. By syncing with a wearable tracking device, users are required to self-track their active lifestyle by participating and completing challenges to get rewards. The application also collects and gives an activity summary of the number of steps and total duration of Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity (MVPA), such as brisk walking, running and bicycling.

Beyond tracking the physical movement of human bodies, the increasing reliance on technological devices to track one’s heartbeat rate is also equally daunting. For instance, Love Alarm is a popular Netflix series that revolves around a technology that enabled users to discover their love by notifying whether someone within the range of 10 metres has romantic feelings for them. While it is a fictional story, I feel that it provides a hindsight to humans’ increasing reliance on technology and wearable devices to manage various aspects of their lives, even for their own romance or emotional feelings which is often seen as immeasurable. Therefore, with these various examples, I questioned whether these data collected ultimately benefit the user or the parent company itself.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 9: Performing Chinese Masculinities on Dating Apps (Soon Poh Suan)

In Chan’s Performing Chinese masculinities on dating apps: Interpretations, self-presentations, and interactions, Chan examined the way in which Chinese heterosexual men perform and negotiate their masculinity through interpretations, self-presentations, and interactions on dating apps. With reference to dating apps such as Momo and Tantan, Chan asserted that dating app will only reproduce the existing gender hierarchy if men cannot see gender dynamics as a positive-sum game. Chan highlighted three interrelated aspects of the use of dating apps, which are:

1) Motivations and interpretations. Based on users and gratification theory, there are diverse uses of dating apps to seek gratifications such as seeking social approval, looking for romance, seeking sexual experience, improving social skills, preparing for travelling, distracting oneself from work or study, and more.

2) Creating and browsing profiles. The initial impression of someone whom one meets on dating sites or apps is entirely built upon the online profiles.

3) Managing connections and conversations. The access to a large pool of dating prospects creates an issue of choice overload.

With reference to Connel’s hegemonic masculinity, Chan asserted the ideal Chinese masculinity can be achieved through balancing wen and wu which can be constructed and negotiated via the above three aspects of the use of dating apps.

Upon reading Chan’s article, I strongly agree that intimacy with people became an irony in today’s world. Beyond the context of China, I find it contradictory that dating apps allow users to gain access to meet a larger pool of people but only to use filters to set age or height range or rely on algorithms to calculate the match percentage between the user and other person. As Chan asserted, apps “provide them with many options, yet they must then screen people out because there are too many options.” This issue of choice overload affects the satisfaction level with one’s selection. With multiple ongoing conversations, the chances of establishing intimate or genuine connection with the other person via dating apps are often lowered and left users feeling less satisfied with their selection of people. For instance, the usual advices we hear on “how to kickstart a conversation” with the other person adopts an interaction script or a checklist mode of standard topics to begin conversations and look for potential partners in the quickest way possible. Therefore, while it feels as though new media technologies subverted the conventional dating norms where more control are given to users to initiate contacts with potential partners, dating apps are unlikely to allow users to fulfil their gratifications of forging intimate relationships with each other.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 8: Mobile Phone Games as a Distraction (Soon Poh Suan)

In Bown’s Unproductive Enjoyment: ‘A Culture of Distraction’, the author asserted that this distraction is a counterpart to the idea of ‘worthwhile’ or ‘fulfilling’ enjoyment. Instead, Bown argued that mobile phone games are used as an example of an enjoyment that is seen as nothing more than a distraction and an unproductive use of time. With reference to the workplace, these enjoyable distractions by mobile phone games served as a form of destressing the stress caused by our unenjoyable work. It worked to hide the alienation and prevent organized rejection of working conditions. Bown’s two case studies, Candy Crush and Football Manager (FM), were used to explore the different kinds of a culture of distraction, to pass time and seize any moments of boredom, leaving us in a constant state of entertainment. For instance, Candy Crush is seen as a distraction as it simulates a feeling of satisfaction people ‘return to work’ and reinforces the sense that our work has coherent order and value. However, FM is a cultural phenomenon which had an influence on the real football world it simulated. Through competition with others, the appeal of FM makes users feel ‘invincible’ by experiencing simulated ‘success’. Hence, while Candy Crush works by hiding and feeling of ‘work stress’, FM produces pleasure to subjects by passing over from the ‘passivity of the experience’ to ‘the activity of the game’.

While I understand the negative implications of the mobile phone games on users such as serving its purpose as a distraction, I still remain hopeful that games can bring about more positive effects in reality. For instance, while Candy Crush is seen negatively as a distraction for people to remain in the ‘work mode’ and mindlessly playing the game, I believe that it ultimately allowed people to relieve stress from their work. Similarly for FM, the simulation of real football world allowed people to feel the sensation of ‘career success’ which may not be easily attained in their real-world jobs. Furthermore, such simulation games also allowed people to take on the ‘ideal’ role of a football manager, which potentially opened up more career options in the real football industry. For instance, as mentioned by Bown, a deal between Everton FC and game manufacturer Sports Interactive in 2008 allowed them to access to the game’s database to scout for more talents. Additionally, student Vugar Huseynzade was promoted to the manager of FC Baku’s reserve team based on his success in FM.

Hence, I still strongly believe that games can bring about more positive effects in the real world. For instance, the fact that games such as Kahoot are often included in the education field demonstrated its usefulness in engaging and simulating pleasure amongst players. Although the lack of agency and the reinforcement of interpassivity, the symbiotic relationship between agency, pleasure and interpassivity can enable people to better project themselves through the use of games in the social construction of reality.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog Post 7: Building an intelligent society through a social network (Soon Poh Suan)

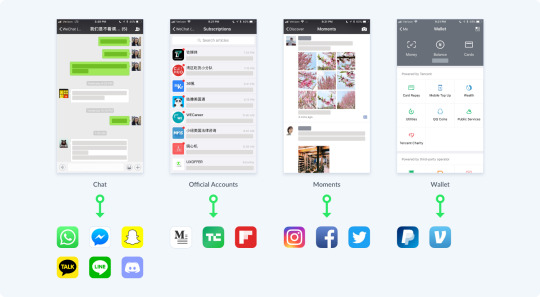

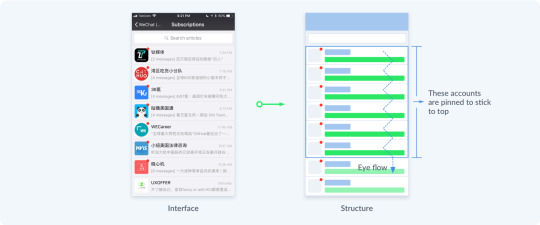

In WeChat: Social Network and Smart City, Zhang, Munoz and Hannien explored the study of WeChat, started from higher-class and gradually normalize to the citizens of China. With the rapid growth of the Internet of Things that gave birth to the “smart city”, the widespread use of smartphones, wireless Internet communication and easy access to new application technologies led to the advancement of WeChat, a “super social network” combining online and offline communications (real-life communication).

Integration of WeChat. Source: https://medium.muz.li/what-makes-wechat-so-successful-5d4795c96e1d#:~:text=WeChat%20is%20so%20successful%20because,letting%20us%20go%20anywhere%20else.

For instance, the main function of WeChat was instant messaging, similar to WhatsApp, with integrated and improved functions of WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, Skype and mini-programmes. Additionally, WeChat Pay is also the main service of instant and cashless payment, making it the most used social network with greater commercial value. Hence, these multiple functionalities in the application which included marketplace, payment method and operating systems integrated new usage and rapid expansion in forming a new communication consumption framework. For instance, people are able to share their daily means of transportation such as bicycles and cars by unlocking through their mobile phones and riding them wherever. These “public services” effectively provide the Chinese citizens with daily needs and link various stakeholders such as the government, e-commerce, residents and properties together to create a smart city. Thus, the innovation of WeChat, the social network’s integration of multiple functionalities improved the information technology and services of the city. Eventually this social platform curates and develops people’s tastes and quality of lives.

User Experience. Source: https://medium.muz.li/what-makes-wechat-so-successful-5d4795c96e1d#:~:text=WeChat%20is%20so%20successful%20because,letting%20us%20go%20anywhere%20else.

With that, I agree with the authors’ analysis on WeChat platform. With the Chinese government’s strong push for digital currency, WeChat’s easy access to multiple functionalities was easily implemented across the country. Aligned with Bourdieu, this digital technology initiative that was first started by the higher authority eventually influenced their citizens to obey and comply with the digital transformation. Eventually, the use of mobile phones and WeChat to facilitate in daily needs is normalized across many parts of China. For instance, the use of digital, cashless payments are widely implemented, even in places such as hawker centres.

WeChat is just like an ‘all-in-one’ app with very streamlined browsing experience, online stores to convert users into consumers and integration of other social apps. The online stores and social apps largely used to influence users’ tastes and urge to shop by ensuring seamless user-friendly experiences. This cultivates a particular sense of culture and quickened the pace of the Chinese citizens consuming media and information.

However, with such rapid economic and technological growth, disadvantaged groups are often easily left behind. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a widely circulated news story of an old man was stopped from taking the train when he failed to produce his electronic health code. Thus, while these super apps facilitated China’s growth, it also contained inherent pitfalls, such as forming ‘in-groups’ and ‘out-groups’ in the society.

References:

Huang, Y.P. (December 28, 2020). How digital technology is transforming China’s economy. East Asia Forum. Retrieved from https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/12/28/how-digital-technology-is-transforming-chinas-economy/

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 6: Precarity and Labour (Soon Poh Suan)

In What Is the Sharing Economy, Ravenelle first defined the sharing economy as platforms that focus on short-term income opportunities even though it claimed to bring financial sustainability and flexible work. With reference to Juliet Schor, the sharing economy activities can be classified into four broad categories, namely the recirculation of goods, increased utilization of durable assets, exchange of services, and sharing of productive assets. Subsequently, Ravenelle’s article explored three major themes. Firstly, the distrust and lack of connection between individuals resembled more of gesellschaft (society) than gemeinschaft (community). With reference to Lyft and Uber, Ravenelle asserted that consumers are more interested in lowering costs and greater convenience. Hence, instead of the desire to ‘share’ with each other, consumers lack the interest to foster long-lasting relationships. Secondly, the increasing short-term casualization of labour lacked a proper long-term contract to protect these gig workers, leading to a shift in risk to these workers. Ravenelle asserted that gig workers were termed as independent with no protection or responsibility from the company. This transfer of financial risk created more flexibility and side incomes for employers while created more job insecurity for the gig workers. Thirdly, with the expropriation of positive terms for marketing, such as sharing, trust, disruption and autonomy. In fact, these workers were being downgraded of the value of labour where there are limited measures to ensure the safety of these workplaces.

At this point, I strongly agree with Ravenelle’s arguments on the dark side or negative effects of the gig economy. Working for these platform economies only focused on short-term benefits such as flexible work, but not all benefits equally and creates pressing issues such as financial insecurity, discrimination, lack of career progression. According to Hern, the gig economy often trapped workers in a precarious existence where more time and effort is required from the gig workers to devote to the platform in order to remain financially stable. For instance, based on my father’s personal experiences, while he only viewed his role as Grab Driver as a means of gaining side incomes as he travelled to work in the morning and back from work in the evening, he often grumbled that Grab should give the drivers extra incentives to cover their fuel costs. Apart from flexible earning opportunities, these drivers are also constantly under the pressure of doing well and securing high rating for every ride.

Overall, I still remain hopeful regarding the future of gig economy. With the mediatization of these technologically enabled systems, consumers are grown to using these platforms as essential parts of their everyday lives. For instance, I have known several friends who frequently called for Grab or Gojek due to many reasons, such as inconvenient location of their homes or even their lack of time management. Thus, these platform economy will continue to stay and prosper with the growing demand from consumers even though the outlook of these technology companies taking more responsibility to ensure more labour protection rights of these gig workers does not look promising.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 5: Family Influencers (Soon Poh Suan)

In #familygoals: Family Influencers, Calibrated Amateurism, and Justifying Young Digital Labour, Abidin (2017) explored family influencers, one genre of microcelebrity, sustained by an undercurrent of “filler” content where the routines of domestic life are shared with followers as a form of calibrated amateurism. Abidin delineated the key difference between Reality TV families and family influencers which is that Reality TV families are often known for their extraordinary achievement whereas family influencers are ordinary, everyday, and mundane. Their productions is usually always self-directed and their output is primarily disseminated on social media, unlike Reality TV families who usually appear on mainstream media. Furthermore, Abidin also discussed how parents justify digital labour of young children through four main mechanisms. Firstly, emphasising their children are experiencing joy, having fun and displaying enthusiasm as willing participants. Secondly, parents regularly allow children to have some editorial discretion and agency to shape the content being produced and takeover some aspects of domestic filler content. Thirdly, parents demonstrate children’s consent to participate or semblances of disallowing children to participate as part of their disciplining. Lastly, parents assure audiences that their children are still “normal kids”.

I agree with Abidin’s argument that these mechanisms are problematic to young digital labour. For instance, famous local YouTubers and influencers such as Jianhao Tan, Xiaxue and Naomi Neo often document their lives and lives of their adorable son or daughter. These influencers used these snippets of their domestic lives as a strategy to be relatable with their followers, which not only increase their appeal to convince followers that they are “family” before “influencers” and place more priority on ensuring the care, well-being, and enjoyment of their children above their commerce. We often see followers leaving comments such as #familygoals which shows their envy to emulate their unity and family spirit too. While I enjoyed the adorable photos and videos of their young children, I also found it distasteful that they have placed their children on a high public profile and scrutiny on the Internet at such a young age. This may be problematic in the sense that it is nearly impossible for them to express their consent to accept or reject it. These children may be unable to fully comprehend and express their stance on the future implications on their growth and adulthood. Hence, similar to Abidin, I do not agree that these justifications made by family influencers are valid reasons.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 4: Media Industries (Soon Poh Suan)

Harrison’s Reflections on the Amen Break: A Continued History, an Unsettled Ethics explores the ethics of convergence – copyright, plagiarism and remix culture. The author first define the two different and distinct concepts of copyright infringement and plagiarism. The former involves legal violation while the latter is a form of ethical misconduct by copying works of others and claiming as its own. This separation of concepts set an important foundation for Harrison’s claim that there is a blurring boundary between copyright, plagiarism and remix culture. According to Harrison, he argues that culture is being (re)produced through the “everyday act of copying”. Harrison used the example of Amen Break — which was a source material used from a recorded music to art installation to YouTube video and to Economist article — to assert the blurry lines between copyright infringement and plagiarism. Harrison also asserts that every act of borrowing should strive to acknowledge the source material, which could be something as simple as citations in essay writing or as complex as the careful manipulation of established visual codes.

Overall, I strongly agree with Harrison’s argument as we live in a globalised world. Cultures are constantly exchanging and reproducing via the use of digital technologies. In turn, the exchange and reproduction of culture then shape our own identity. During the tutorial discussion, I vividly remembered an example given in class which provoked deeper thoughts on how copyright infringement is an inescapable issue, something that never has been an easy and explicit matter to handle due to the globalising world we live in.

(Screenshot from the Music Video: https://youtu.be/6a6mFypGsmI?t=1078)

A kNOCkout contestant in a local YouTube channel Night Owl Cinematics, rewrote song lyrics and rearranged bits and pieces to a remix song. The judges then critiqued that such acts of assembling different parts and songs may involve copyright infringement issues. Similar practices are prevalent in the music industry. Whenever artists make song covers or remix, they would always cite the original singer and song to avoid the legal violation. In some sense, Harrison’s argument of “copyleft” is in line with the practices of the culture industry, which is to acknowledge that the source material is being taken in the circumstances.

Harrison, N. (2014). Reflections on the Amen Break: A Continued History, an Unsettled Ethics. In The Routledge Companion to Remix Studies (pp. 454-462). Routledge.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 3: Mobile Media (Soon Poh Suan)

Tussey’s The Procrastination Economy: The Big Business of Downtime analyses the relationship between mobile device use and the spatial and technological constraints of the commute. Tussey first defined the procrastination economy as a variety of subscription services that offer leisure and communication apps that make the ride to and from work a social occasion. Commuters not only seek to separate themselves from their surroundings and enjoy an audio-visual experience during their rides, but also allow them to interact with their friends, family and larger cultural conservations. Commuters are also usually busy text messaging their loved ones or playing their preferred songs according to their context, mood and taste. Interestingly, advertisers identified commuters as busy professionals charging through their workdays and pursuing money which would be spent shopping online during their commute back home. Hence, marketing messages and posters are designed noticeably in order to catch commuters’ eyeballs instantly.

Tussey’s assertion on the role of mobile media deeply intrigued me in understanding how mobile media mediated people’s identities and relationships on a daily basis. For instance, I observed that one common way of parents pacifying their noisy young children during public rides is to allow them to be engaged with portable devices in exchange of gaining quietness and peacefulness as they are able to browse through their own phones. While I do not agree with their ways, this observation is in line with Tussey’s argument on how mobile media has fostered and deepened social bonds and behavioural norms such as quietness and privacy among commuters.

(Source: https://www.brainpulse.com/articles/6-mobile-marketing-statistics.php)

Furthermore, I am also inclined to agree that commuters are not passive, but rather, active users who are busy text messaging and interacting with their loved ones or playing preferred songs according to a specific context. Based on my personal experience, I remember looking forward to long bus or MRT rides because I could indulge in listening to my favourite playlist or podcasts in Spotify while mindlessly scrolling through Instagram feeds. These were precious moments where I felt isolated from my surroundings and could afford to take a breather from hectic, fast-paced lifestyle. In rare occasions where I do not have my wireless earpiece, I will feel unusually uncomfortable as I was the only person in the crowd who has nothing to do on hand. Yet, these were also the fulfilling and peaceful times where I pay more attention to my surroundings and listen to conversations or interactions between commuters. This difference in experiences made me realized the impact of mobile media entering our everyday lives (mediation) and in turn, influenced how we are interacting with one another in public transportation (mediatization).

Overall, I strongly resonated with Tussey as the sense of individualism and disconnectedness allows commuters to be isolated in a ‘cocoon’ and disallows disruptions or anxieties from their surroundings. Mobile media has played a significant role in creating an economic opportunity for advertisers to cater a wide variety of products and services to fulfil the needs of these commuters, people who require a portable personal space to rest in order to cope with the demands of the world today.

Tussey, E. (2018). The Commute: "Smart" Cars and Tweets from Trains. Chapter 3 in The procrastination economy: The big business of downtime. New York: New York University Press. Pp. 74-109.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 2 – Role of television in our homes (Soon Poh Suan)

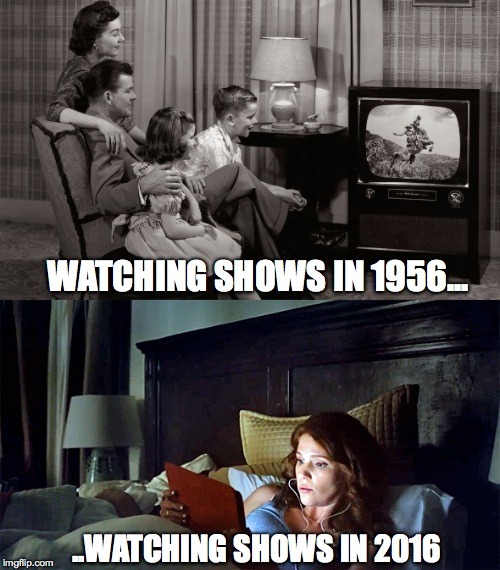

In Spigel’s TV and the Spaces of Everyday Life reading, Spigel asserted five main arguments of the television studies. In essence, Spigel first maintained the television’s continued place as a spatial apparatus and as a symbolic object in domestic spaces. Secondly, Spigel posited the television’s relation to suburbanization and privatization of public amusements. The creation of home theatres cultivates a “fortress” mentality where television can provide privacy, security as well as a form of luxury and comfort to consumers. Thirdly, Spigel contended the television’s centrality to ‘mobile privatization’ and fantasies of virtual travel. Furthermore, television provides a sense of liveness and ‘telepresence’. Lastly, Spigel also argued that the television has predominantly shifted from a domestic medium to a mobile technology and “everywhere” cultural form. The television is not only our ‘window to the world’ but also has extended itself from our private life into public spaces with the emergence of digital media.

I strongly agree with Spigel as I related to my own personal experience of how the emergence of digital media changed the television industry and my family dynamics within my domestic space. Spigel’s perspective coincides with the layout of my home and speaks truthfully about my family unity and division.

(Evolution of watching shows. Source: https://imgflip.com/tag/television?sort=top-2016)

To begin with, my living area is the first to be noticed when one enters our home. When my brother and I were young, our family usually eat our dinner by 7pm at the dining area and proceed to watch television programmes together. However, as we grew up and the emergence of digital media such as Netflix, my brother and I are usually preoccupied with our sources of entertainment from devices such as laptops, phones, and iPads. The variety of devices could cater to our different needs and interests, and we do not have to compromise with each other to watch the same programme together. Hence, while the television set is deemed to be an essential item in our home, our family hardly gathers around the living area to watch television programmes together anymore. Apart from our parents who would still be sitting in the living area and watching local news at the stipulated times, my brother and I normally sit at our study area or in our rooms. This change in family dynamics is saddening as the television used to be a bonding time for my family to interact and have quality time with one another after a long day of work and school.

(Binge Watching TV shows on Netflix. Source: http://www.anchorsaweighblog.com/2015/02/how-we-watch-tv-binge-watching.html)

Yet, Spigel’s reading made me understood the impacts of digital media technologies on families and our domestic spaces. The shift and change from television and mobile technologies was even more apparent and mediatized in the time of COVID-19. According to Dixon, streaming services have boomed even more rapidly during the rise of the global COVID-19 pandemic as lockdowns began all around the world. MeWatch, a local streaming service by MediaCorp that is striving to keep up with Netflix, has offered a steady stream of local shows. These personal experiences with digital media made me realize how digital media has forced its way through or mediated in constructing our everyday reality, reshaped and mediatized the workings of the television industry and consumers’ everyday reality.

References:

Dixon, I. (2020, May 9). The rise and rise of Netflix in a time of coronavirus. Channel News Asia. Retrieved from https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/netflix-television-coronavirus-covid-19-quarantine-lockdown-tv-12714118

Spigel, L. (2015). TV and the Spaces of Everyday Life. In Mediated Geographies and Geographies of Media (pp. 37-63). Springer, Dordrecht.

0 notes

Text

Mediatization (Soon Poh Suan, A0202791J)

In Chapter 2 of The Mediated Construction of Reality, Couldry and Hepp introduced the concept of social world as a communicative construction of everyday reality. They asserted that communication, and specifically mediated communication, contribute to the social construction of reality. Indeed, our everyday lives are interwoven with communication and media. This relationship has been even closer to one another with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The interplay of connections between various mediated realities converge and integrate into habits and norms of communicative practices and eventually shape how people make sense of the world. In essence, social worlds are not just mediated but mediatized with the role of media in the process.

Upon reading Couldry and Hepp’s piece, I strongly agree that these technologically based media of communication institutionalize our communicative practices – that is, to materialize and naturalize the level of forms and patterns of our practices. For example, instant messaging platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram are my go-to communication platforms.

Image of the differences between WhatsApp, Telegram and Signal.

Source: https://fractionalciso.com/whatsapp-vs-signal-vs-telegram-security-in-2020/

Taking reference to the screenshot image above, WhatsApp is largely used for work-related messages and calls while Telegram is used for casual conversations with my friends and university course mates for group projects. With the “secret chat” function and “public” username, Telegram ensures more privacy and hold conversations without saving other users’ contact numbers. Thus, I resonate with Couldry and Hepp that the social world is differentiated with the different symbolic resources of media — in particular to this example, the different features of WhatsApp and Telegram — but they also sustained communication across and intersect with one another. As these communicative practices increase, these patterns of institutionalization became a form of habit and norm amongst many of us and part of our everyday reality.

Additionally, I also strongly relate to their argument with the extensive use of video-conferencing platforms. Zoom, Skype and Google Meets became increasingly prevalent in schools, businesses and workplaces especially during the early phase of Circuit Breaker. As people source for a variety of options, these three main video-conferencing applications gradually shaped the different purposes of usage and ingrained in people’s minds. Firstly, Zoom is widely referred to the more comprehensive application to be used for business and workplace communication. Secondly, unlike Zoom, Skype is more commonly used for informal calls with friends and family. Thirdly, while Google Meets falls behind of Zoom and Skype due to its lack of intuitive features in the interface, it is also generally used for smaller groups of business and workplace communication. Thus, these three video-conferencing platforms often overlap, form connections with one another and institutionalize people’s communicative behaviour and practices.

To conclude, Couldry and Hepp’s reading was fascinating with the introduction and unpacking of the term ‘mediatization’ and relatable to my personal experiences with media.

Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2017). The social world as communicative construction. Chapter 2 in The mediated construction of reality. Cambridge, UK;Malden, MA;: Polity Press. Pp. 15-33.

1 note

·

View note