#*images rock n roll is our epiphany

Text

Mandy Sacs: Fitness Girls Shoot (2023)

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

a wizard/a true star is fifty

some folks was even higher than me – but probably not too many

“It isn’t supposed to be for having major epiphanies. It’s supposed to be for looking at colorful shit.”

I still recall how intensely I resisted my sister’s advice – seldom the choicest instinct. She was my sitter, uniquely predisposed as she was and is to equanimity and sweetness. Of the two of us, I tend to be the handful, and she has enough patience and self-control for both of us – sometimes I wonder if I left mine behind in the womb for her. Anyway, she’d brought two tabs of LSD, a gift from a boy she lived with who shared her name, a former child prodigy violinist who’d completed his descent into defiant chaos. Drug-dealing was a part of this, and it’s another testament to my sis that she only ever did a few bumps of coke, in such proximity to his tundra of a stash. I’d have ended up at the “being murdered for pinching” part of the process in weeks, and I don’t even like cocaine – though that’s mostly because I’ve never tried it, having somehow sustained a rule to avoid anything that could kill me.

She’d had her first experience with acid that summer, nearly five decades after the of-love one, and neither of us could say if the stuff in our possession shared one molecule of ‘60s acid’s chemistry – the stuff that woke the Beatles up, and spurred them in 1967 to blur the lines between rock ‘n’ roll and some wondrous something else. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was the first album to come clad in a self-consciously artistic garb: the world’s most famous band disguised in mustaches and multicolored marching band outfits, the unwieldy misdirect of a title printed on a bass drum and BEATLES spelled out in flowers. In books they loved (Through the Looking Glass et al.), Lennon & co. had learned how to translate the beguiling mystery of dreams into text. For three LPs, climaxing with Pepper, they’d more or less invented the music for it, too.

That kicked off a little epoch of people trying to do the same – my favorite in pop history. Every sound was new, all prior rules relaxed as fresh ones were being fashioned. The “rock” music of that ’67-‘74 era – a wild mass art project which for me includes Stevie Wonder and Joni Mitchell’s tonal palettes – eludes description. Music itself is remarkably emotional, endlessly communicative beyond the purely verbal. It’s a mysterious, potent substance, these infinite combinations of waves. Short of a more inventive image, Pepper and its descendants were radiant splashes of color bleeding through greyscale lines, indelibly staining blank canvas with unprecedented tints and shades. Even decades ago, people tried to wave their hands through that pink smoke with complaints about Western chauvinism and “high art” gentrification. But to me, it’s surrealism + genderfluidity + pure melodic rapture. You say you want a revolution?

Drugs were the primary engine of a lot of this effort. But by the mid-‘70s, which were a long time ago, even the best art-rock sounded washed out – overfed and overfunded. The hippies’ sweet dreams had barely weathered a dark night of the soul in full swing just a year after they’d hit full flower. But even without a ‘68 to bring everybody down, the fact remains – few dreams survive daybreak. And the waking dreams drugs deliver do usually crash into some kind of foggy hangover, “that elusive feeling” alcoholics talk about reliably dragging them closer to the gates of insanity or death. As for me, I first tried a drug – marijuana – just in time for my 21st birthday, after a youth spent getting high on people and rarely subduing my lows. It did feel like a waking dream – and as with any other addict, that enchantment came to haunt me. No common sense could keep my cat-curiosity from pulling me toward a second try.

Just a few years later, the obsession was total. My rock bottom was still a long way down, but anytime I could get my hands out of my empty pockets and on something which promised a buzz – an escape from reality’s perpetual itch and unrelenting anxiety – I made sure I did. I invited myself anywhere that held the promise of a shared smoke, and when no such invitation/intrusion was available, I credit-carded locked doors and quietly opened drawers minutes before the absent party returned. On a particularly audacious occasion, I found my way through a window I’d only hoped would be so easy to jigger open on the ride over. So often is marijuana insisted to be non-addictive, yet I went to insane lengths to disprove this, with no intention of sharing the data – the hiding, a product of the shame, is a huge part of addiction. I wasted time dreamin’ of the myth of California sobriety, but I was as much a mess as anyone stuck in their cups.

The accumulation of highs puts you sorely in the red on time and money you’ll never get back, and distances you from the longer-lasting highs you could, and ought to, build toward. But along with peacing (when not freaking) you out, drugs might, at their friendliest, convince you that you can see for miles and miles and miles. Oh yeah. What is it about, say, a THC high? It illuminates and then softens the barriers between you and the ether, that magical otherworld glimpsed in dazzling flashes but so elusive, drowned out by reality (or is it society?)’s dutiful buzzkill. It really connects you with something that does feel cosmic or spiritual or otherwise enlightening, and it can lead to breathtaking external or internal connections, or – if you happen to be an artist – invaluable arrangements of elements not otherwise discoverable. At its most benevolent, it can make artists of us all. But is the art you make true enough to be worth it, when it’s not you creating – it’s you through some disorienting filter?

Why I’d waste the actual prime of my life on all those fuzzed-out “highs” speaks to questions I’ve yet to answer. Other than being a lifelong self-sabotager, there’s no solid explanation available. Some of the motivation, though, lies in that first night I ever tried LSD. My quest for profound realizations was thwarted by a sudden inability to properly complete sentences. This did not ease my passage to becalmed bliss, and eventually my sister accepted that while I would probably prevent myself from enjoying/embracing the experience, I also wouldn’t die. She left, but it’s OK. She reclaimed her night, and I reclaimed my sanity (such as it was) by discovering how much nicer Can’s “Future Days” and Parliament’s “Flash Light” suddenly felt – my sister’s advice in vivid action.

I once read a quote about a researcher of some kind discussing two test groups of scientists, boldly exploring the frontier of recreationally ingesting mind-altering substances (for science). It was something about the marijuana users sitting around discussing life’s most profound questions, and the LSD users sticking their fingers in their bellybuttons. My only worthwhile experiences on LSD the three or four stomach-churning times I tried it that summer were musical. This translated to marijuana, which at least did me the favor of not disabling communication (and by extension, creativity). But in general, I was not asking profound questions while on weed – I’d just hole up and let my mind wander, with music becoming my most irresistible companion.

Frankly, the harmonic and structural advancements THC spurred in music I wrote were indispensable – bar its inconvenient side-effect of keeping me from finishing 80% of my ideas. The music I replaced these incomplete masterpieces with was an endless stream of Spotify playlists, glutted with mostly “art rock” from mostly the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Much of it was designed for something like weed – you have no reason to play a Yes album more than once otherwise. I distracted myself from the fact that I was merely distracting myself with so much art whose sole purpose was to capture the whims of its perpetrators’ wasted minds. Still: in a big-beat, multi-track format, that approach can yield some real fun. Just marvel at the complete works of the second-chiefest (after sex) pleasure of my brief LSD patch, Jimi Hendrix, who died chasing his extraplanetary visions, but sure sounded dynamite giving them life.

Fifty years ago, Todd Rundgren, who like a lot of painfully white folks loved Jimi Hendrix, had ended up on the same astral plane Jimi crashed in. Having avoided drugs for ages, the better to maintain his uptight aloofness (and develop those acrobatic arrangements, and produce like nine other albums a year), by 1973, he was in a position to spend a lot of time and money getting audibly smacked sideways by substances. The hardest thing he’d taken before had been Ritalin, which resulted in the double-disc talent tour Something/Anything. But after disliking his first taste of psychedelics (DMT, the one where you have that fleeting field trip to a land of elves), Todd fell headfirst into his own head. What he saw made him hear beautiful music only he was capable of concretizing.

“I became more aware [through psychedelic drug use] of what music and sound were like in my internal environment, and how different that was from the music I had been making,” Todd told Mike Myers’ brother, who proved himself an excellent reporter (and très enthusiastic fan) for a 2010 biography. “My new challenge was to try to map, as directly as I could, the various kinds of chaotic musical element[s] in my head.” The artist began to externalize these mad visions by building himself a studio, and enlisting fellow musical utopians in the reification of his own flights of fancy. The resultant A Wizard/A True Star was an hour long – a two-LP length. But Rundgren crammed it onto one record, risking the loss in fidelity for his magnum opus in order to honor its unbroken sides. Wizard is the white Electric Ladyland: a production fantasia only a talent as hyperactive/producer as unkempt as Todd could’ve fashioned.

The standard for headphone music fifty years ago was the clean dreariness of Dark Side of the Moon, the first rock LP where all technological shortfall has been eliminated from the recording process. But Rundgren’s facile pop confections reliably share two characteristics – impudence and impatience. At his best, these qualities are more temperate – don’t let Mark David Chapman scare you off the brilliant (if deceptively deep) Ballad of Todd Rundgren. Yet a lot of times Todd’s natural insolence is what makes him fun – makes him punk, albeit a punk who’d never give up pop. He remains the corniest musician ever to secure Patti Smith’s stamp of approval (Blue Öyster Cult are close), but even she’s ignited by his messy genius. “Clever as a fox, my spirit lights,” she says in a poem Wizard included. “Spirit laughing free as water, in a ring of fire, with its hair aflame.” Todd had dyed his hair three neon colors that season.

Few records are as nice a listen high as Wizard – which inevitably means it loses a little luster when you’re not, its flaws magnified in the first rays of the new rising sun. It is the surest proof of one sad principle: the music intensifies the wonder of the drugs, but the drugs don’t deepen the meaning of the music. In any case, Wizard pulls out all the trippy tricks beautifully at its beginning. It kicks off with a fractalized tone dancing from one corner of your brain to another. Then the simulated sound of a rocket’s billowing plumes, then a slurp up to the stars on some synthesizer setting, and finally, a resonant keyboard ostinato Pete Townsend might give his sad-eyed nod to. It’s as if AI were told to synthesize “far out, man!” into a piece of music, and AI had a trace of wit (yet). It spills into a wonderful pop song, one which actualizes the automatic agape of psychedelic euphoria. “International Feel”’s pretty chord sequence that helps spruce up its words, which are only not nonsense under certain conditions.

(There is more) international feel

(And there’s more) interplanetary deals

(Still there’s more) interstellar appeal

(Still there’s more) universal ideal

“I only want to see if you’ll give up on me,” he sings. Decades later, he bragged during a commencement speech about how Wizard halved his audience, touting it as an example of the valiance of following your own nose. Not terrible advice for a graduating class – but an arguable misreading of what his endeavor represented. Wizard was designed as mass outreach, but when Todd turned on, it turned people off. Alienation is no virtue, and it’s definitely no way to establish a utopia. The fact is, so many drug users imprisoning themselves in their own heads think the things they’re conjuring up in there would set the entire world free – but good luck getting a coherent message across when you’ve returned to Earth. So the fun of this record is in its self-referential games, not its cockeyed aperçus, a technicolor extrapolation of Something/Anything’s cute “sounds of the studio” interlude. “Just as surely as I’m in your ears”, he winks at you at one point, and I can never for the life of me remember the second half of that thought.

After “International Feel”, Todd drifts into a number from the Mary Martin Peter Pan before the primary fear of a “head trip” hits – that the good part will fade soon (better get more!). “Tic, Tic, Tic (It Wears Off)” takes you on a cheerful march through the LP’s main style – intricately layered synthesizer doodles, unless Todd is picking up his guitar and brontosauring around in the manner of the most indulgent Roy Wood. It resembles Something/Anything’s “Breathless”, though wiggier and more whimsical, which is welcome. At its most arbitrary, Wizard feels like nothing more than exercises in overdubbing – but if you’re in an altered mindstate, everything is illuminated. He then crashes into a song that bellows “WHAT YOU NEED IS YOUR HEAD”, even as the artiste sounds like he’s lost his. The album is usually either a kaleidoscopic confluence of alluring cadences, or a lot of weird shit piling up around you.

It doesn’t puncture the dreamlike aura, but “You Need Your Head” unleashes Todd’s mean streak, which no magnitude of good vibrations can subdue. For a willow of a wunderkind, at his worst, Todd was a notorious asshole. Though the bar was low enough to reach, the vitriolic “Rock ‘n’ Roll Pussy” is a much weaker song than the contemporary work of its target, John Lennon. Of all those impotent dogfight insults, the word “pussy” – so sensual in its other sense – is especially noxious. Lennon was a far gentler spirit than Rundgren, but Rundgren has the advantage of never dealing anything but verbal blows. “Pussy” is commendable for calling this out, but when Rundgren took it farther in offhand comments, he got his ass handed to him, in the finest thing Lennon wrote in 1974.

After that, Rundgren layers himself pretending to be dogs laughing for another transitional minute – it’s annoying, but not ineffective, especially if you’re in that tense interval every high guarantees. This whole sequence of vignettes slides by so fast, and is so disorienting and unprecedented, that it can be a rush in context. But as I write about it, the meaner-spirited it all feels. This is especially true of the supercute but indefensible “You Don’t Have to Camp Around”, on which Todd (who somewhere on side B sings “my voice is so high, you would think I was gay”) confers upon himself the authority to call out the queer male community’s “mincy lisping” as some kind of pose. Wilde might smirk at the “tssss-ts-ts-tssss” vocal percussion, but mostly, it's typical ‘70s hate humor. The permission it thinks it gives for gay men to liberate themselves from already liberated behavior is a condescension that could only spew forth from a giant fucking dick.

Still, it’s in keeping with the concept, which is apt for a drug album: Whatever Just Occurred to Todd, verbally and musically. Yet another arch instrumental (“Flamingo”, get it?) blends into side A’s captivating, perplexing centerpiece, “Zen Archer”. It seems bent on being a battle hymn for Martians, and the lyrics scrape at significance without ever getting there. But as it gives way to a swirl of harmonies (a Rundgren specialty, that callow, childish voice going all angelic in a choir of itself), and as those simulated arrows soar between your ears, you’re under the wizard’s spell, and buying everything the true star is selling. On a song like this, the endless sardonics lighten a heavier tread – Todd is too sarcastic not to palliate self-serious caprices such as this.

Still there’s more. Todd impersonates a nightmare oompah band on “Just Another Onionhead”, another set of words the drugs told him were profound enough to write down (“the falling of the hare“, “prime cut of baby’s butt”). It switches on a dime to “Da Da Dali”, an ersatz Al Jolson croon over an atomized jumble of deliberately fucked-up Tin Pan Alley chords. Then comes “When the Shit Hits the Fans; Sunset Blvd.”, another blast of macho-rock – as Todd sings elsewhere, “I play my guitar in such a man-cock way”, and this proves it again. One of the ways Wizard best flatters a high is how you can let your mind wander about fifteen minutes in and you won’t miss anything. But when it all surges back into “International Feel”’s glorious refrain, well. You feel like you’ve really been somewhere.

As I inferred earlier in this piece, I didn’t want to take drugs to turn my mind off. Todd has spoken of the same objective. Trouble is, when you take drugs, you’re not necessarily likely to strengthen your mind. Indeed, you’re ceding its control to an occupier that can’t think, but sure has some ideas about how you should be doing it. Even a few years into my abuse of weed, I recognized that what I appreciated about it was uncomfortably close to one of alcohol’s many dubious assets: the parameters of its impairment momentarily strengthened a focus. (Being a millennial means having ADHD – like Todd – so I shudder to imagine how many problems of mine a first sniff of cocaine might appear to solve.) It’s just an illusion, and all its confusion will catch up to you sooner or later. Some of Wizard’s players crowed to Paul Myers about how nice the muddled-ethereal chords are for “Sometimes I Just Don’t Know What to Feel”, but the lyrics prove its clearest thought is the titular one. It vies for incisive, but ambles toward aimless.

That song is an uncertainty manifesto: a self-negating oxymoron. But the parts that aren’t dour or overambitious are really gorgeous, and the rest of side B is a string of some of the nicest pearls ever to form in an acid-addled noggin. “Does Anybody Love You” boasts a master melodist’s most effervescent melody, and the auteur’s chirping vocal improves one more unaccountably bitchy lyric, knocking a mirror-gazing narcissist of the female persuasion. (He was with Bebe Buell at the time, a person who’s made a career of her own promiscuity, and who inspired another talented sexist, Elvis Costello, to pen his most vituperative tunes.) It's a testament to Todd’s equal-opportunity nastiness that he manages to sling mud at the vain and the self-disgusted (“love between the ugly is the most beautiful love of all”) in the same two-stanza track; it’s a testament to his voracious taste for sweeter melodies that he cloaks this dagger in one of the sweetest.

He then spares us further transitional crotchets by borrowing some of the most beautiful melodies of all. Like so many Philly musicians, pop-soul was in Todd’s blood. To kick off the medley in this side’s middle, he chooses one exquisite hit each from the genre’s greatest innovators, Curtis Mayfield (the Impressions’ “I’m So Proud”) and Smokey Robinson (the Miracles’ “Ooh Baby Baby”). The choices are astute – two of the dreamiest songs by two of the dreamiest writers, who shared a gift for sifting disarming emotion out of the harmonic atmosphere. The songs’ mutual tone is so gentle and compassionate that the long break they offer from Todd’s uncut ego dissolves any bad taste he’s left. I wish he’d gone with Chairmen of the Board’s “Give Me Just a Little More Time” or the Five Stairsteps’ “O-o-h Child” over the Delfonics’ “La La Means I Love You” for his third, but his bratty delivery adds an odd resonance to its innocence, and he would’ve ruined those other, better songs anyway. And though his 7/4 rendition of “Cool Jerk”, the medley’s conclusion, is another burst of buzzy racket, for once, the music justifies the discord.

After the dumb “Hungry for Love” – which always flies by even though it technically hangs around for two minutes too long – come two cuts, one feather-soft and one diamond-hard, which pull off the unusual trick of partially justifying their own toxic politics. “I Don’t Want to Tie You Down” is the most vulnerable Todd ever let himself be in front of a microphone, a rare concession that the double standard men impose on liberated women (a still-fresh concept in 1973!) is bullshit. As I-fucked-up songs go, it’s a blue valentine. “It gives my life a bit more meaning to feel in love with you,” Todd admits, letting his codependency show. But he sees this shaky foundation, and a glimmer of saving-grace interdependence: “The balance of our minds together, the perfect give and take/for me to let my love possess you, that would be my worst mistake”. Only once does he compulsively mar his own perfect picture, cracking his paper thin voice as he leans into the one stupid line he allows: “oh JEsus/I don’t want to nail you down.”

Then there’s the striking “Is It My Name”. An ardent, searing plea to some ladyperson who doesn’t want to deal with Todd’s bullshit, there’s plenty of it to step in throughout the lyric – not just the gay voice-“man-cock” couplet, but the indecipherable chorus itself. Is Todd’s hypothesis that she doesn’t want to go out with him because he’s too famous (haha), or because he has one of the unsexiest (Rundgren) names (Todd Rundgren) in rock ‘n’ roll history? And does he seriously not know that’s not it? But the opening line is “there is cause and effect/there’s a reason I’m so erect”, and it’s belted with such openhearted urgency, the crotch-rock of it all is dispelled in the sheer candor. Its extended coda is a clunky blizzard, but if your mind was blurry to begin with, this feels like a real climax. Then he closes out with five flawless minutes: “Just One Victory”, as celestially empowering an anthem as was ever divinely dictated to a nerdy white pseud.

I spent ten years high on not just weed but the same small chunk of pop history. I eroded my resolve against the hippie era’s long-disproven false promises with a dangerous cocktail: records, mixed with stronger and less pure intoxicants than the stuff they had back then. A horribly destructive bout of alcoholism – that habit is a whole year kicked – pulled me away from pot for a hot minute. But I still tricked myself into thinking that being a clean half century away from 1973 meant I should drown myself in its music, which, barring some anomalies, was either painfully pillowy or deliriously droogy. That year was peak bleak ‘60s hangover, and while I’m glad coke and quaaludes aren’t all the rage anymore, I gobbled enough space candy to simulate each, tearing myself off my own yellow brick road. And I frequently returned to “International Feel”, giving into the urge to tickle my brain with the same distressingly impermanent hour on trips that got me precisely nowhere.

I don’t know what Todd and I were looking for – escape, I suppose, a version of consciousness featuring frills only mirages can provide. In any case, he never got where he was trying to go either – his next three records, Todd, Todd Rundgren’s Utopia and Initiation,took unchecked psychedelic doodling well beyond the humanly tolerable. Because Todd’s best work (productions for other artists aside) was behind him by 1973, I’d forgotten how self-parodic and sanctimonious so much of his later work could be, even after he’d rediscovered form’s function. He was so talented, I have a permanent soft spot for him, and I was licking my lips reading the effusive descriptions of heavenly harmonies on the much later Nearly Human’s “The Waiting Game”, which Todd claims he dreamed. Put it on and you hear ‘80s hell. Rundgren is too sharp today to suspect he stayed stoned, but I wonder how unblown a mind can become. The loss of whatever he traded away was a fatal one.

I’ll never forget the soul-settling luminosity of the opening notes to Jimi’s “Burning of the Midnight Lamp” as I enjoyed them coming down from a no-fun high (so many of them are no-fun highs), while laying back in my neighborhood pool after dark. But the reality is, you don’t need any substances to really dig Electric Ladyland – it gets you there anyway. Wizard is the ultimate drug LP; drop the 3-D glasses, and watch its dimensions flatten. And much of the last decade’s pop, be it trap or the sugary soundscapes of Charli XCX (who sampled Todd on an early mixtape), does the waking dream thing better. As more earthbound sounds seep onto the charts again, I uneasily realize that much of what I’ve been up to all this time is diluting one high with another one. The best music will transport you all by itself. To insist on conjuring up clouds to admire it through is to pull a curtain between you and the art – and even worse, you and the life the art is there to affirm.

1 note

·

View note

Text

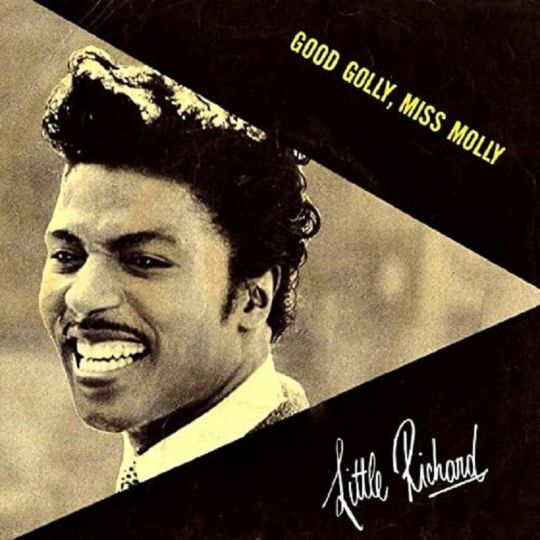

Little Richard: Rock and Roll Legend Died at the Age of 87

Little Richard, best known as Little Richard, who mixed the black church's sacred yells with the profane blues sounds to make some of the world's first and most influential rock 'n' roll songs, died in Tullahoma, Tenn, Saturday morning. He was 87.

His lawyer, Bill Sobel, has said bone cancer was the cause.

Little Richard never invented rock 'n' roll. By the time he released his first single, "Tutti Frutti" — a raucous song about sex, his lyrics cleaned up but its sense was hard to miss — other musicians had already found a similar vein in a New Orleans recording studio in September 1955. Chuck Berry and Fats Domino had reached the top 10 of the rock, Bo Diddley had topped the rhythm and blues charts, and for a year Elvis Presley had made hits.

But Little Richard, delving deeply into the wellsprings of gospel music and the blues, pounding the piano vigorously and shouting as if for his own life, lifted the energy level to many notches and produced something not quite like any music that had been heard before — something fresh, exciting and more than a little dangerous. As Richie Unterberger the rock historian put it, “He was crucial in upping the voltage from high-powered R&B into the similar, yet different, guise of rock ’n’ roll.”

The label for which he released his greatest hits, Art Rupe of Specialty Music, named Little Richard "dynamic, completely uninhibited, unpredictable, wild." "Tutti Frutti" rocked up the charts and was soon followed by "Long Tall Sally" and other music now known as classics. His live performances were so amazing.

"He would just burst out from anywhere onto the stage and you could not hear anything but the audience's roar," record producer and arranger H.B. Barnum, who played a saxophone early on in his career with Richard Penniman, recalled Charles White's authorized biography in "The Life and Times of Little Richard" (1984). "He would be on stage, he would be off stage, he would be jumping and yelling, screaming, whipping the audience on."

An Immense Impact

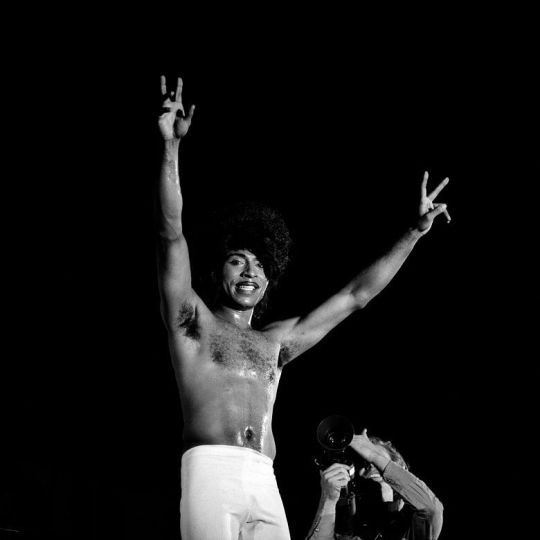

Rock 'n' roll was in its early days an unabashed macho music, but Little Richard, who had performed in drag as a teenager, posed a very different image on stage: gaudily dressed, his hair piled up six inches high, his face aglow with cinematic makeup. In later years he was fond of suggesting that if Elvis were the king of rock 'n' roll, he was the queen. He described himself as homosexual, bisexual and "omnisexual" in different ways offstage.

His success as an artist was incalculable. It could be seen and heard in James Brown's flamboyant showmanship, who idolized him (and used some of his musicians when Little Richard began a long hiatus from performing in 1957), and in Prince, whose ambisexual image owed him a great debt.

Presley has captured songs from him. A octave-leaping exultation, the Beatles adopted his signature sound: "Woooo! "(Paul McCartney said the first song he ever performed in public was" Long Tall Sally, "which he later recorded with the Beatles.) In his yearbook for high school, Bob Dylan wrote that his dream was to" join Little Richard.

The impact of Little Richard was very social as well.

Mr. White quoted him as saying, “I’ve always thought that rock ’n’ roll brought the races together.” “Especially being from the South, where you see the barriers, having all these people who we thought hated us showing all this love.”

Mr. Barnum told Mr. White that when Little Richard sang, "they still had the audience segregated" at concerts in the South in those days, but that, “most times, before the end of the night, they would all be mixed together.”

If uniting black and white audiences was Little Richard's point of pride, it was a source of concern for many, particularly in the South. The North Alabama White Citizens Council released a rock 'n' roll denunciation primarily because it put "people of both races together." And with several radio stations under pressure to keep black music off the air, Pat Boone's clean-up, toned-down version of "Tutti Frutti" was a bigger success than the original Little Richard. (He even had a "Long Tall Sally" hit) Still, it seemed like nothing could hinder Little Richard's rise to the top, until he himself stopped it.

He was at the height of his fame when, in late September 1957, he left the United States to begin a tour of Australia. He was tired as he told the story, under constant pressure from the Internal Revenue Service and angry at the low rate of royalties he earned from Specialty. He had signed a deal, without anybody to inform him, which gave him half a cent for every record he sold. "Tutti Frutti" sold half a million copies but only netted $25,000 for him.

One night in early October, he had an epiphany in front of 40,000 fans at an outdoor Sydney arena.

"Russia sent that very first Sputnik off that night," he told Mr White, referring to the first satellite that had been sent into orbit. "It looked like the huge ball of fire was going straight over the stadium about two or three hundred feet above our heads. It made my mind shake. It just made my head shake. I got up from the piano, saying, "This is it. I am through. He had one last Top 10 hit: "Good Golly Miss Molly," recorded in 1956 but not released until the beginning of 1958. At the time he had left behind a rock 'n' roll.

He was an evangelist on the run. He went into Oakwood College (now Oakwood University) to prepare for the ministry in Huntsville, Ala., a Seventh-day Adventist church. He cut his hair, married and began gospel music recording.

He will be torn between pulpit gravity and stage pull for the remainder of his life.

“Although I sing rock ’n’ roll, God still loves me,” he said in 2009. “I’m a rock ’n’ roll singer, but I’m still a Christian.”

In 1962, he was drawn back to the stage and he performed for wild acclaim in England, Germany and France over the next two years. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones were among his opening acts, and then at the beginning of their careers.

He went on to tour the United States relentlessly, with a band that included Jimi Hendrix on guitar at one time. By the late 1960s, sold-out performances in Las Vegas and triumphant appearances at Atlantic City and Toronto rock festivals were sending out a clear message: Little Richard was back to stay.

‘I Lost My Reasoning’

Alcohol and cocaine began to drain his soul by his own account ("I lost my reasoning," he would later say), and in 1977 he turned from rock 'n' roll to God once again. He became a Bible salesman, started making worship songs again and vanished from the spotlight for the second time.

He is not staying away forever. His biography was released in 1984 and marked his return to the public eye, and he started performing again.

By now he was as much a musician as he was a personality. He played a prominent role as a record producer in the hit movie "Down and Out in Beverly Hills" by Paul Mazursky in 1986. He appeared on television on talk shows, variety, comedy, and awards shows. He worked at celebrity weddings, and performed at funerals for celebrities.

In concert he could still uplift the roof. He stole the spotlight at a rock 'n' roll revival concert in London's Wembley Arena, in December 1992. "Today, I am 60," he told the crowd, "and I still look remarkable." He proceeded to look incredible — with the aid of wigs and heavy pancake makeup as he flew intermittently into the 21st century. But in the end, age took its tool.

He walked onstage with the assistance of two canes by 2007. In 2012, he suddenly ended a show at Washington's Howard Theater, telling the audience, "I cannot breathe hard." A year later, he told Rolling Stone magazine that he was retiring.

"In a sense I am done," he said. "There is nothing I feel like doing right now." Survivors include a friend, Danny Jones Penniman. Full survivor information was not immediately available.

Raised in Macon, Ga., on 5 Dec. 1932, Richard Wayne Penniman was the third of 12 children born to Charles and Leva Mae (Stewart) Penniman. His father was a brick mason on the road, selling moonshine. An uncle, a brother, and a grandfather were preachers, and as a child he attended churches of the Seventh-day Adventist, Baptist, and Holiness, and aspired to be an evangelist artist. An early influence was Sister Rosetta Tharpe, a gospel singer and guitarist, one of the first artists to blend a religious message with the intensity of R&B.

Richard's ambition had taken a detour by the time he was at his teens. He left home and started performing in traveling medicine and minstrel shows, part of a dying-out 19th-century tradition. Billed as Little Richard by 1948—the name was a nod to his youth and not to his physical stature — he was a cross-dressing actor with a minstrel troupe named Sugarfoot Sam From Alabam that had been performing for decades.

He recorded his first songs in 1951, while performing alongside strippers, comics and drag queens on Atlanta's Decatur Street strip. The songs, without distinct style, were generic R&B, and attracted almost no attention.

He encountered two performers during this time whose look and sound alone would have a profound impact: Billy Wright and S.Q. Reeder, who has performed as Esquerita and recorded it. Both of them were professional pianists, glamorous dressers, flamboyant entertainers and as openly gay as it was possible in the 1950s to be in the South.

Richard Penniman acknowledged his debt to Esquerita, who he said gave him some tips for playing the piano, and to Mr. Wright, whom he once called "the most fantastic entertainer I have ever seen." However much he borrowed from either man, the music or persona that emerged were his own.

His break came when Mr. Rupe signed him to Specialty in 1955, and arranged for him to record with local New Orleans musicians. He began singing a raucous yet obscene song during a break at that session which Mr. Rupe thought could attract the burgeoning teenage record-buying audience. Mr. Rupe hired Dorothy LaBostrie, a New Orleans songwriter, to clean up the lyrics; the song became "Tutti Frutti"; and a rock 'n' roll star was born.

By the time he finished playing, Little Richard was a recipient of lifetime achievement awards from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences and the Rhythm and Blues Foundation in both the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (he was inducted in the Hall's first year) and the Songwriters Hall of Fame. In 2010, "Tutti Frutti" was added to the National Register of Congress Library.

If Little Richard ever thought he had deserved all the honors he got, he would never admit it. "Many people call me the rock 'n' roll architect," he said one time. "I do not call that to myself, but I think it is true."

Do not forget leaving your valuable comment on this piece of writing and sharing with your near and dear ones. To keep yourself up-to-date with Information Palace, put your email in the space given below and Subscribe. Furthermore, if you yearn to know about effect of virus on Frank Soo, view our construct, ‘Frank Soo: Google is celebrating England's forgotten footballer.’

Read the full article

#BoDiddley#CongressLibrary#ElvisPresley#GoodGollyMissMolly#JamesBrown#LittleRichard#littlerichardsongs#LongTallSally#LongTallSallysong#Mr.White#Omnisexual#Presley#RichardPenniman#RosettaTharpe#Tullahoma#TuttiFrutti#TuttiFruttisong

0 notes

Text

Investment

I came to the local Starbucks in my town to “do work” and find myself at a standstill because there is the work that I “want to do” and then there’s the reality that neither of these will result in paycheck. There’s a possibility that applying for jobs via NYU career net will result in something. Anything...Maybe.

I don’t want to stay at Jump forever. I enjoy the company but it pays so little and I know that I could be making it just like everyone else who is pursuing their passion, but I don’t invest time in my personal projects for that very reason. Time is a precious thing in this world... sort of... well at least the safety of our assets resides in it.

I woke up this morning from a nap this morning, looked outside my window and thought I was at the beach. I asked my dad yesterday where he would like to go if you could go anywhere. At first, he refused to answer and insisted I share my answer first but after my subtle demanding he said: Bora Bora.

There, he said, you could wake up on the beach, literally roll out of bed and be on the beach.

I found it to be a funny image of someone falling off their bed and drowning from shallow clear waters.

I looked over the old text posts I did on this account and was bemused.

I was taken back by my own ferocity and anguish but also, I don’t remember writing half of those posts.

Interesting what stress can do.

My mom asks me if I remember a lot from when we went to El Salvador.

I don’t.

I remember getting a big chocolate donut, it, of course, being ordered for me (because no habla espanol cuando seis anos).

Those n’s need squiggly on them god damn it.

Why doesn’t the computer recognize that already wtf.

Anyways, I remember a donut, a pool, a hungry coconut eating monkey, and riding on a boat. But that’s it.

Oh! And a place called El Mundo Feliz. I feel like I wrote about it in elementary school at one point. El Mundo Feliz was basically this https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OlSbxMDWIc0

I remember this one little game that looked like a pinball machine in the sense that the components of the game were covered and you would control a little car inside the game with buttons on the outside of the plastic glass. I don’t know why but I remember how aesthetically satisfying that game was.

Now that I think about it, I think I’ve only liked games for the aesthetics of them. Growing up, my brother and I used to play Halo 3 together and I liked that game solely for how gratifying it was to kill someone, the weapons in that game were so pretty.

I had a huge investment in assassins creed (now talk about tying my subject matter in hell ya). I played the first, second, brotherhood, revelations and a little bit of assassins creed 3, black flag and unity. I can’t pinpoint the exact reasoning other than I probably just got bored along the way and didn’t see it being something for me to invest my time into anymore. My coworker Promo let me play the newest game on his computer and it was super fun but obviously, it wasn’t something I considered to be worth my time or money enough.

I follow my intuition when it comes to the investment I guess. But also, when the amount of items I put on my plate in these moments of “time to do work” falls on my own personal judgment, I tend to invest time into what I enjoy doing.

What do I need to do? Apply for scholarships, make money... really that’s all that I need to do for myself. I’d be content with writing or drawing or dressing up or makeup or singing or songwriting for the rest of my life in order to make a buck. But I think I’ve spent the past 30 minutes writing this blog post because it gets me out of my head and it a platform I can access immediately. I’m hoping that the more I write the more I can be connected to myself and the little voice in my head.

Anyways, I think I’m going to end now with a prosed poem.

Imagine

immediately the sand is caught beneath

my feet

longing

waiting

for you to comfort me

for you to hold me

to touch me

to sing to me

but where is your voice??

where is that sweet sin of indulgence you owe to yourself?

to your everlasting epiphanies?

to your wondrous senses?

I believe in a cure for mankind

erratic and fortuitous for the both of us

maple and cured

sweet serenitous baby

do you grapple time

or do you listen to your stomach?

I am in search of darkness

for a multitude of cacophonous rock

of melodic chimes

and distant winds.

I am in search of great power

fearing responsibility and rude awakenings

but welcoming with open palms

You can do it all.

You can put great fury to paper and listen to distant winds.

watch the baby.

He will fall if you’re not looking after him.

Into the water.

Into the fountain of youth.

He will reverse

and grow into the subtle peacock he was born to be

flying over mountains that were never meant to have lightning

or palm trees.

0 notes

Text

Rock n roll is our epiphany: Patrick Jones and a theatrical vision for a young Wales

In recent days, I received my copy of the 10th anniversary edition of Manic Street Preachers’ eighth studio album Send Away the Tigers. I have been collecting Manics’ special editions for some time now. While they sit outside the scope of my electronica radar, I find them musically, lyrically and aesthetically irresistible; indeed, their exceptional artwork is often the reason why I purchase their reissues, rather than James Dean Bradfield’s kitchen demos.

Last year, of course, was the 20th anniversary of their iconic (as a threesome) Everything Must Go, which followed their even more iconic The Holy Bible (when they were a foursome).

Against this backdrop, I have been reminded of my encounter with the early plays of Patrick Jones (pictured above), which I covered when I was a drama critic at the turn of the second millennium. Jones, for those who don’t know, is the older brother of Nicky Wire (real name: Nicholas Jones), feather boa-adoring bass player of the Manics. But he is also one of the most intriguing playwrights I ever came across. Given that I am dipping in and out of the Manics on iTunes these days, I thought I would share some of my writing on Jones’ first two staged plays, which I had the privilege of seeing in 1999-2000. While they were staged during the first term of Tony Blair’s government, the issues they explored seem just as relevant now, if not more so, as when they were premiered. Please bear in mind, as you read on, that the following was written in 2000.

Then came human beings. They wanted to cling but there was nothing to cling to. Albert Camus

The Sherman Theatre in Cardiff is celebrating the millennium with an urgent form of epic theatre. Fusing the wintry apocalypse of 20th century British poetry, the classical paradigm of modern American drama and the nihilistic vision of a teenage wasteland, two powerful and contrasting plays reveal Patrick Jones as a vital new British playwright. This unique voice rejects the muscular iconography of Welsh culture and instead confronts historical and topical manifestations of nationalism and fatherhood.

With the nihilistic pose of punk and the androgynous pout of glam, Manic Street Preachers have always understood the grand gesture. The generation the Welsh rock group represent is largely drawn to the shared hopelessness that Richey Edwards, their original ideologist-in-chief, articulated in a despairing, often holocaustic, lyricism. His disappearance without trace, after episodes of self-harm and anorexia, in 1995 arguably compares with the cultural and emotional significance of Princess Diana and Kurt Cobain.

Provoked by the subsequent media hysteria, Jones was anxious to find a theatrical voice that would eloquently speak out: “The press were saying that rock music is bad for young people,” he recalls. “I wanted an intellectual rebel to look around today and ask what we have become. So I started writing notes for a play about how young people grew up amongst this.” Against an urgent rock soundtrack, Jones reclaims the classical tragedy from Arthur Miller for a youth betrayed by old Wales and the New Labour government.

Libraries gave us power, then came work and made use free.

What price now for a shallow piece of dignity?

“A Design for Life”, Manic Street Preachers

Jones’ first play Everything Must Go* is located in Blackwood, the South Wales hometown he shares with Manic Street Preachers. Under Margaret Thatcher, the capitalist temples of Sony, Toshiba and Pot Noodle replaced the local coal industry. In Phil Clark’s production, which premiered in February 1999 at the Sherman Theatre, beautifully choreographed factory production lines hover menacingly over the stage like an Orwellian industrial nightmare. As piercing shrills of factory hooters punctuate these images, a cacophonic fanfare to the philosophy of “arbeit macht frei” is hauntingly evoked. “It’s creating theatre that works on all your senses,” insists Clark, the Sherman’s artistic director and a highly regarded champion of new plays for young people.

The production inhabits a vastly different universe from the venal commercial instincts of an Irvine Welsh stage adaptation. What transpires is a powerhouse mixture of poetic imagery and an intelligent rock score. This Brechtian model sharpens the play’s dialectic by using popular songwriting to lend immediacy to not only the political issues raised, but also the human cost involved. “We should be looking for more epic forms of theatre,” argues Clark.

Opening with “A Design for Life”, this urban hymn to the British welfare state sweeps rhapsodically over an apocalyptic scene of youth culture in the Welsh valleys. “It allows the audience to enter into the dramatic world of the play,” explains Clark. Another song called “Ready for Drowning” translates the Stevie Smith metaphor into a polemic about how recent British governments have divided communities with free market economics. This nightmarish sequence shows a group of miners leaving the pit, before being placed in front of computers they are clearly incapable of using. As frustration turns into farce, one by one, the miners pick up their monitors and throw them into the pit hole, while the light from their helmets pierces the dark auditorium. “An understanding of the working-class voice and the structures of our society has always been of use to the next generation,” reckons Clark.

Only takes one tree to make a thousand matches.

Only takes one match to burn a thousand trees.

“A Thousand Trees”, Stereophonics

The narrative, however, pivots around the enigmatically named A, a rebel archetype in a similar mould to Quadrophenia’s Jimmy or The Catcher in the Rye’s Holden Caulfield. As the play’s title infers, a plague of retail outlets has reduced Blackwood to a shuttered fortress. Better still, an anarchist’s playground. “The dilemma Patrick brings up in the play,” Clark suggests, “is that, even though A identifies what’s wrong, he doesn’t know what to do about it.”

Politically inspired by Aneurin Bevan, A has the ideal canvas on which to graffiti the social ills he sees around him – want, ignorance, squalor, disease and idleness – which the founder of the NHS sought to eradicate. More poignantly, Bevan’s message actually sounds like a modus vivendi for a modern Wales. “The message I get from young people is more cynical than the punk vision,” adds Jones. “I want to show that, if they had A’s awareness, it would give them empowerment out of all this.”

A is originated by a remarkable young Welsh actor called Oliver Ryan, who understands the protagonist’s iconoclasm and the ambivalence of his situation. “He’s terrifyingly well read,” says Ryan. “But he has built his own world through newspaper clippings, Welsh history and Karl Marx. He has to make it seem real to him. There’s so much sadness in A because he doesn’t realize that he has a voice. Instead, he chooses to destroy in order to create, which I think is very apt for teenagers today.”

This mentality is intelligently juxtaposed with Ryan’s mesmerizingly ethereal character in Unprotected Sex, Jones’ play by Jones, which premiered at the Sherman Theatre Studio in October 1999. Appearing as a sullied glam rock angel, Denver is the victim of childhood bullying who sought refuge among the mountain ponies and found solace in their need for companionship.

Witnessing the murder of a pregnant mare by knife-wielding thugs has heightened his selfless despair: a solo choir voicing the isolation and destructiveness of this grotesque rite of male initiation.

Acting as a counterpoint to Denver’s introspection, Richard Harrington’s portrayal of Gary, a former soldier, is a sensitive antidote to the Charles Bukowski image of manhood. What social skills the army taught him are the brutalizing, if childlike, means of control used to inspire discipline through some kind of surrogate family loyalty. Abandoned by his father at a vulnerable age, he is seemingly perfect cannon fodder. But military life has denied him the full range of emotions to deal with the atrocities he witnessed in Kosovo. The war still raging inside his mental universe, he returns to Triste, his pregnant girlfriend, with only alcohol and testosterone as support.

Returning to Everything Must Go, the dominant focus of A’s rage is to avenge the loss of his father, a former miner whose death was hastened after being sacked following a decade on a production line without any explanation. “It’s about how, with a click of the mouse, his father was gone from the workforce,” says Jones. In the apotheosis, extreme personal morality, rather than sociopathic dysfunction, inexorably propels A to kill Worthington, the factory manager responsible for sacking his father. “There’s a certain rage when words are not enough,” Jones accepts. “I’m not saying that killing someone is the answer. But I don’t think there was another way, dramatically, in which he could prove his point. He’s not going to be a politician or a pop star and he cares so much about his father.”

Every day when I wake up, I thank the Lord I’m Welsh.

“International Velvet”, Catatonia

The betrayal of the human spirit underpins the damning indictment of Blair’s Britain, which drives Everything Must Go. For A’s friends, empty days are filled with material dreams, petty crime and a perverse determination to survive. There’s Pip, who is more interested in the next sexual conquest than political idealism; there’s Jim, who never seems to learn from the Open University TV programmes that keep him up all night; and there’s Curtis, who, denied an identity at school, speaks only in song lyrics from époque-making groups, such as The Who, Nirvana and Oasis. “It’s brilliant you have to pay to listen to young people, telling you how they feel,” enthuses Oliver Ryan, “because this is the generation that everyone is so quick to dismiss.”

This popular cultural sensibility is employed with greater subtlety in Unprotected Sex. Admittedly, there is a hypnotic score from James Dean Bradfield of Manic Street Preachers, which resonates through this compelling example of physical theatre. Meanwhile, the lyrical sense of poetry mirrors the social disintegration of TS Eliot’s The Wasteland, which, in its time, commented on a crisis in the human condition. Moreover, it convincingly evokes the claustrophobic intensity of Edward Albee and Tennessee Williams.

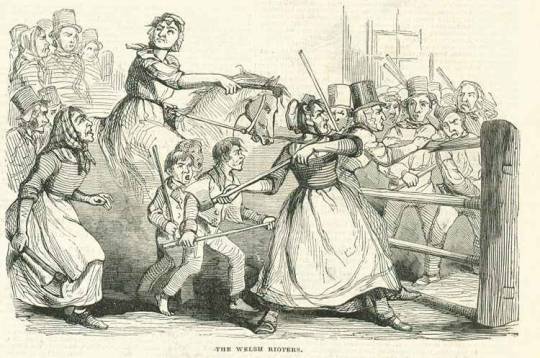

Jones attempts to resolve the patriarchal conundrums that – from the Rebecca Riots to the tribal machismo of the rugby field – are posed (but not exclusively) by Welsh society. In each play, a female character – both stunningly portrayed by Maria Pride – offers poignant insights into maleness and its relationship with national identity at this millennial juncture. As masculinity implodes around her in Unprotected Sex, Triste becomes the voice of hope, while Cindy in Everything Must Go has to deal with her disgust and frustration at what Wales has become through self-harm and heroin abuse. “I’m sure part of me hates a lot of the old Wales,” believes Jones. “But part of me relishes what it was. We don’t really celebrate Bevan. Instead, we’ll have the Welsh national anthem only sing on the rugby pitch by ‘real’ men with a tear in their eye.”

Dr Stephen Gregson

Co-founder

Language and Culture

* Although the Manics’ album Everything Must Go was released in 1996, it took its name from Jones’ play, which was in draft form at that stage.

If you enjoyed this blog, check out Fuse, a collection of plays and poetry by Patrick Jones, published by Parthian Books.

0 notes

Text

Mandy Sacs: Fitness Girls Shoot (2023)

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

@r0sebudz

Mandy Sacs: Fitness Girls shoot 2023

#images - rock n roll is our epiphany#mandy rose#c: amanda#mandy sacs#amanda saccomanno#body image tw

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Say @fkapaige whatever happened to these proper battlers?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Equally hot on top and bottom @r0sebudz

#c: amanda#*images rock n roll is our epiphany#images taken before soup#smoking tw#alcohol tw#wce#tags upon tags

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prepare yourselves England

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve always quite enjoyed 4 July through the years.

Always wondered what we’re celebrating however?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA: @r0sebudz now has her own merchandise line available on fangear dot VIP.

Tees, hoodies, his and hers shorts that go to support the artist, the muse, this dog and helps keep her out of my bloody closet. Please shop heartily and enjoy your product!

Customer service is standing by, but don’t call me after ten PM or you’ll hate what you hear.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spoiler Alert: this was absolutely not the collab that I suggested or thought it was. @r0sebudz

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you see this on the beach, no you didn’t.

@r0sebudz

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

@myownkingdxm joins the Judgement Day : 6 May 2023

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also for context, I’ve no issue with Prince Harry and his decisions. I just needed a quip to burn some dead air.

Also we’ve extras of these shirts to sell on the Fantime

@twcstedjacy @r0sebudz @dvlins

1 note

·

View note