#And who we choose to support and uplift will be our demise or salvation

Text

Why are you so angry all the time? Why do you lock yourself away from the world? Why are you not living your life they ask?

I answer with my own set of questions. How can I live in a body that doesn’t work? In a house divided? In a mind that constantly races? How can I go out and try to make a living when I know off the back of my labor my money goes to funding genocide? How can I think positively and go out and have fun when children are being gun downed for going to school, the movies, the mall? Is this survivor’s guilt? It can’t be. I don’t feel guilty for surviving. I feel rage and sorrow that I have to survive. I should be living. We should be living. One shouldn’t have to struggle to eat, drink, and have basic healthcare and rights.

#We can’t right all the wrongs in this world they say#People will always be doomed to repeat history they say#But we all have the power to choose. One person can’t change the world on their own#but one person can start a chain reaction!#And who we choose to support and uplift will be our demise or salvation#*steps off soapbox*#ironically hate religion so much but this sounds very pastoral#once again baffled by the stupidity and cruelty of humanity#us politics#what a country#free Palestine#free Congo#free Haiti#free everyone from their colonizers and oppressive regimes#this post won’t do anything but pls what you buy#the films you watch the musicians you support it all literally adds up#religion is shit ppl in charge are shit I’m never leaving my room again#anygays…#ok to rb

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Frances,

Iola Leroy; or, Shadows Uplifted (1892) centres on the eponymous heroine, Iola Leroy, the daughter of a white slave owner and one of his slaves. When the novel opens, we are at some point during the American Civil War, and a group of slaves meet in secret to discuss the Union army’s progress. Forbidden to congregate, they hold clandestine prayer meetings in the woods. They are talking in code about the war, so as to hide their knowledge from their white owners. Most of them desert their owners and join the Union army, and one of them informs the Union commander of a young woman who is being held as slave in their vicinity. Her name is Iola Leroy, and they decide to rescue her.

The story then jumps back to the years prior to the war, and we follow Iola’s story. Her father, Eugene Leroy, was a wealthy slaveowner who had survived a serious illness through the care of one of his slaves, Marie, who was one-quarter black. He fell in love with her, set Marie free, sent her to a northern school, then married her and had three white children.

Eugene decides to raise Iola, Harry, and Gracie as white, to protect them from prejudice. They were educated in the North and their black ancestry was hidden from them. While at school, Iola even professes a pro-slavery stance. However, when Eugene suddenly dies of yellow fever, his cousin, Alfred Lorraine, decides to make use of legal loopholes to overtake Leroy’s property. Lorraine goes to court to declare Marie’s manumission illegal and her marriage is then annulled. She and her three children revert to slavery and are separated and sold away by Lorraine, who becomes the heir of Eugene’s fortune.

The plot shifts back to the war, when Iola has been rescued from slavery and becomes a nurse in a military hospital. She then receives a marriage proposal from a white medical doctor, Dr. Gresham, who initially professes to be against miscegenation. Upon knowing about Iola’s black ancestry, he asks her to hide it from others and to pass as white. The novel explores her struggle with the question on whether or not she should pass as white and hide her ancestry, so as to make her life easier and take advantage of opportunities for assimilation into white society.

This is a topic that would be explored many times later in literature, such as in Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1928) and Passing by Nella Larsen (1929), and you take a clear stance on it: embracing black identity is a more fulfilling experience for the characters, even if it means that they will have to confront racism to find a job or a house. Further, you make clear that, by asking Iola to ‘pass as white’, Gresham is not only exercising a (not so) subtle form of oppression, but also romanticizing her past as a slave as well as fashioning his role as some kind of ‘white saviour’.

You explore not only the personal but also the political implications of ‘passing’, and, such as in Harriet Wilson’s Our Nig, or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black (1859), you also dismantle the conflation of skin colour, social class, civil rights, and morality, as well as criticize the racism of northern white Americans who were used to think of themselves as ‘more enlightened’ as their southern counterparts.

As Iola sets out to find her mother and bring her family together, she strives to improve the conditions of black people. Caught in the intersection of racial and gender oppression, she struggles to assert her professional independence as a woman during the post-war Reconstruction period.

Such as in Geraldine Jewsbury’s The Half-Sisters (1848), you explore the idea that the fact that a woman has a career does not endanger her womanhood, but rather enhances her roles as wife and mother and contributes to a better family life, as a source of self-respect. Further, you seem to equate enforced domesticity with moral corruption. “”Uncle Robert,” said Iola, after she had been North several weeks, “I have a theory that every woman ought to know how to earn her own living. (…) I think that every woman should have some skill or art which would insure her at least a comfortable support. I believe there would be less unhappy marriages if labor were more honored among women.””

Through conversations between the characters, you incorporate discussions (and speeches) on religion, racism, the rise of violence against black people, temperance (the discussion on the damaging effects of alcohol, as part of a larger discussion on male violence against women), women’s rights, assimilation, education, moral progress, and the movement for equal rights for black people. “”Slavery,” said Mrs. Leroy, “is dead, but the spirit which animated it still lives; and I think that a reckless disregard for human life is more the outgrowth of slavery than any actual hatred of the negro. “The problem of the nation,” continued Dr. Gresham, “is not what men will do with the negro, but what will they do with the reckless, lawless white men who murder, lynch and burn their fellow-citizens”.”

The novel incorporates genres such as slave narrative, sentimental novel, historical fiction, social protest, and the coming of age narrative, as well as political and social commentary. I particularly liked the use flashbacks and dialect throughout the novel, and the fact that its main political ideas are incorporated through conversations conveyed in dialect, providing not only a black perspective but a black voice. You seem to link the topics of how slavery fractures the family unit and how racism fractures one’s notion of identity – particularly racial identity, as in the case of ‘passing’. “I ain’t got nothing ‘gainst my ole Miss, except she sold my mother from me. And a boy ain’t nothin’ without his mother. I forgive her, but I never forget her, and never expect to. But if she were the best woman on earth I would rather have my freedom than belong to her.”

The subtitle of the novel – “(…) or, Shadows Uplifted” – seems to suggest racial and civil empowerment, as well as the release from the shadows of war and slavery. “The shadows have been lifted from all their lives; and peace, like bright dew, has descended upon their paths. Blessed themselves, their lives are a blessing to others”. It also hints at religious enlightenment and salvation, at the uplifting of the afflicted, as you explore the moral contradiction of slavery and Christianity: “But, Mr. Bascom,” Harry said, “I do not understand this. It says my mother and father were legally married. How could her marriage be set aside and her children robbed of their inheritance? This is not a heathen country. I hardly think barbarians would have done any worse; yet this is called a Christian country.” “Christian in name,” answered the principal”. Finally, the subtitle also points to the lifting of the “veil of concealment” represented by the act of ‘passing’, and to a defence of the assertion of black heritage and black identity.

Iola Leroy resists the literary convention of the “tragic mulatta” and its conflation with the “fallen woman” trope to evoke sympathy in a white reading audience: your book does not portray miscegenation as a catalyst to a female character’s demise, and you refuse to use Iola to placate white readers. She is her own woman.

Iola will eventually choose her black heritage, and you frame this choice as one of truth and moral fortitude over (white) appearance and shallowness. Some have read this framing as a conservative choice in its disavowal of passing (which they read as a disavowal of miscegenation and equality); to me, however, particularly in the context in which you were writing, your framing reveals ‘passing’ as a subtle form of oppression and the need of assimilation into white society as a conservative stance.

The highlight of the book for me is the fact that it encompasses a variety of black experience, from slaves to freed blacks to mixed-race characters to black intellectuals and the black upper class: it is a jam session of black voices, with an underlying, radical beat of resistance and hope.

Yours truly,

J.

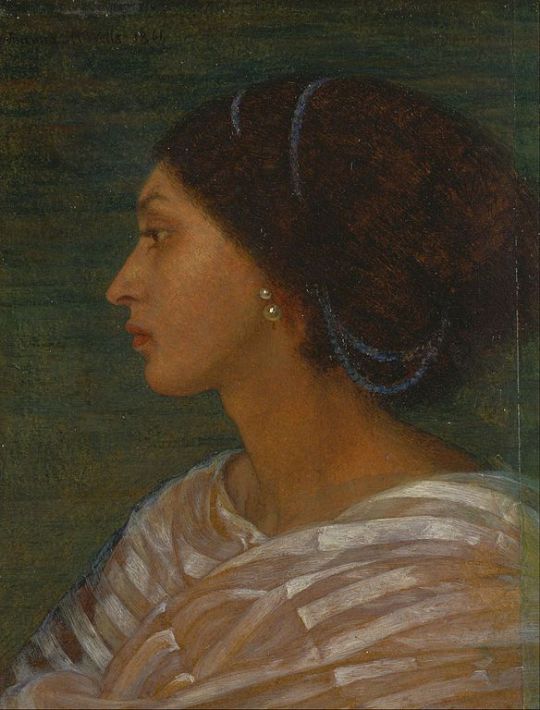

‘Head of Mrs Eaton (Fanny Eaton)’ by Joanna Boyce Wells (1861)

“Miss Leroy, out of the race must come its own thinkers and writers. Authors belonging to the white race have written good racial books, for which I am deeply grateful, but it seems to be almost impossible for a white man to put himself completely in our place. No man can feel the iron which enters another man’s soul.” – Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Iola Leroy: Shadows Uplifted

*

Now, Captain, that’s the kind of religion that I want. Not that kind which could ride to church on Sundays, and talk so solemn with the minister about heaven and good things, then come home and light down on the servants like a thousand of bricks. I have no use for it. I don’t believe in it. I never did and I never will. If any man wants to save my soul he ain’t got to beat my body. That ain’t the kind of religion I’m looking for. I ain’t got a bit of use for it. Now, Captain, ain’t I right?” – Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Iola Leroy: Shadows Uplifted

*

“Miss Iola, I think that you brood too much over the condition of our people.” “Perhaps I do,” she replied, “but they never burn a man in the South that they do not kindle a fire around my soul.” – Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Iola Leroy: Shadows Uplifted

*

One day a gentleman came to the school and wished to address the children. Iola suspended the regular order of the school, and the gentleman essayed to talk to them on the achievements of the white race, such as building steamboats and carrying on business. Finally, he asked how they did it? “They’ve got money,” chorused the children. “But how did they get it?” “They took it from us,” chimed the youngsters. Iola smiled, and the gentleman was nonplussed; but he could not deny that one of the powers of knowledge is the power of the strong to oppress the weak. – Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Iola Leroy: Shadows Uplifted

About the book

Broadview Press, 2018, 352 p. Goodreads

Penguin Classics, 2010, 256 p. Goodreads

Beacon Press, 1999, 320 p. Goodreads

First published in 1892

My rating: 3,5 stars

Projects: The Classics Club; A Century of Books; Back to the Classics, hosted by Karen

My thoughts on Iola Leroy; or, Shadows Uplifted (1892), by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper #readwoman #readsoullit #zoracanon Dear Frances, Iola Leroy; or, Shadows Uplifted (1892) centres on the eponymous heroine, Iola Leroy, the daughter of a white slave owner and one of his slaves.

0 notes