#I love how the gold looks together and how it shimers

Text

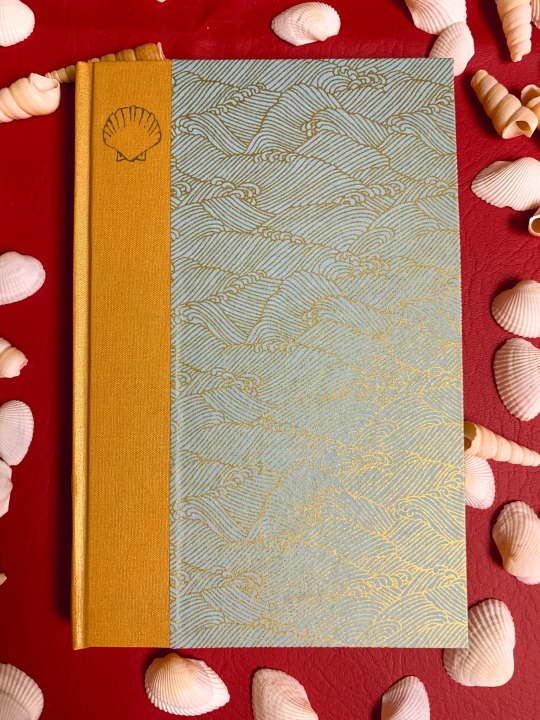

Todays bind! Fools Gold, by @tigers1o1 !!

Personally, I absolutely adore the paper and bookcloth combination on this bind. I got the cloth a while back for free and I’ve been waiting for a chance to use it, and then my friend Cam got me this paper as a gift! It seemed way too perfect to not use!

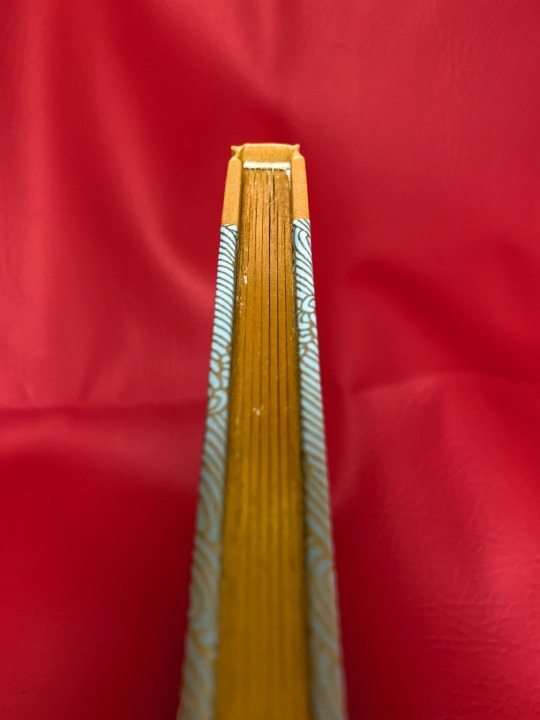

This was a very exciting bind, because it gave me the opportunity to try something completely new, gilded edges!!

Although it didn’t turn out perfect, I’m still super proud of how clean it ended up. Plus, I personally think the flaws make it better :D

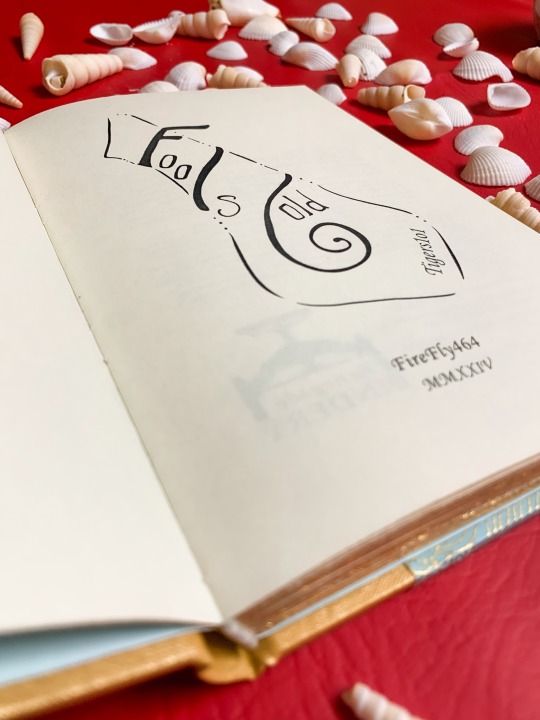

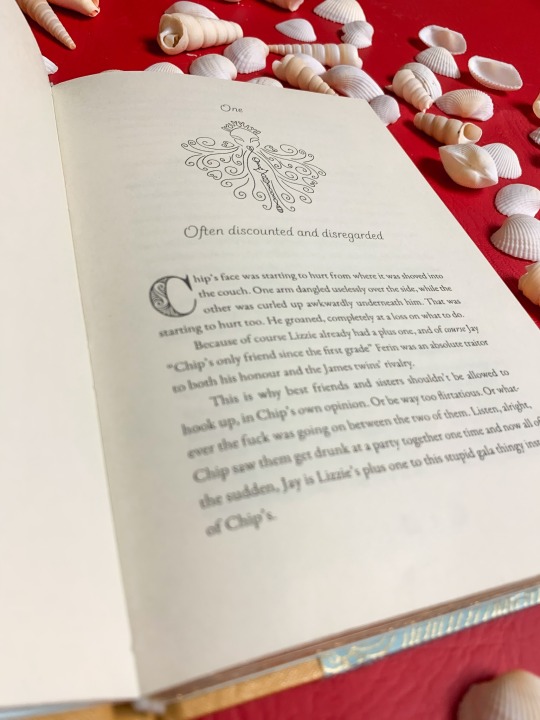

The typesetting here was very exciting for me. A few months ago Ty held a tattoo contest for the fic, and I couldn’t not use them when I saw the two finalist designs. So I went ahead and contacted the artists, and they both said I could use them!!

Title page design: @eldrigeonsss

Chapter header design: @sheeeeeeeepherd

Thank you both again for letting me use your beautiful work!

You can read the fic here: https://archiveofourown.org/works/42798252/chapters/107512251

#guys I’m so proud of this book you have no idea#I think it’s one of my favorite books I’ve ever made#I love how the gold looks together and how it shimers#the bookcloth and the paper both shimmer and it’s SO pretty#plus on top of that this binding let me meet some really really cool people#and helped me unlock some super cool opportunities#so it’s definetly going to be one I hold close to my heart for a long time#also major shoutout to Indy and Ty for letting me borrow the red leather and the shells for the pictures#it worked out so much better than I ever could have hoped#fish n chips#jrwi show#just roll with it#chip jrwi#fish and chips#jrwi fnc#gillion tidestrider#ficbinding#firebound press#renegade bindery#fanbinding#bookbinding

254 notes

·

View notes

Note

Angst Idea: Shape!Traveller shifting into their sibling at night. They fall asleep hugging themselves and crying, muttering soft 'i love you's and other things they never got to tell them :'( (they shift back after they've fully fallen asleep)

Missing The Other Half | Genshin Impact | Aether

If only Lumine could see him now.

Curled up on his side, hugging nothing but the empty air, Aether allowed himself to losely cross over one another as the shakey sigh of longing left him. Paimon slept soundly, small, deep breaths filled his ears while the wind blew gently against the tent.

But other than that, there was an empty silence.

A silence that made Aethers mind swirl with doubts and longing.

His heart felt cold, hollow, the pain of not having the last of his family within arms reach grew into a destructive and depressing force. Strong enough to cut through the ice that slowly to frost over the hope of finding Lumine again, the 'what ifs' started to build, and the tears started to build behind his eyes.

The subtle shift felt like nothing, deep and long golden locks became short and in the color of lemon and daffodil, eyes losing the peach tone of warmth and now becoming solid and sharp. The browns, golds, and dark colors of Aethers clothing shifted into a dress, white as freshly fallen snow and tained with the shimering teal and honey that could only be found in celestial planes.

A small whimper leaves his throat, but it isn't his, it's hers. Her voice, filling her ears, but it's his mind that suffers in the lack of her real presence.

God's, even with everyone in Teyvat- Mondstat to Snezhnaya, he can't seem to fill that hole in his heart. Bit how could he? Aether has only had Lumine, and Lumine alone, since his birth. They traveled worlds together, had breaks without one another, but in the end they came back. They always came back to each other.

But there's a doubt in his mind, it lingers, and settles into the darkest parts of his mind.

It's there as he fades into sleep, his delusion of comfort with it, and hes back to the look that he was born with.

Will she ever come back, willingly?

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Justin Olsen Will Get Lost

New Post has been published on https://www.articletec.com/justin-olsen-will-get-lost/

Justin Olsen Will Get Lost

Feb 8, 2018

Justin Olsen’s start is perfect.

It’s a frigid November evening in Park City, Utah, and the gold medalist’s final run on Park City’s bobsled track. After three races and two days competing against twenty-three teams at the Bobsled World Cup, this will earn him the points he needs to get to Pyeongchang.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

The four-man team hunkers down in the bullet-shaped sled: Olsen first, in the driver’s seat, with three push men (responsible for furnishing a thigh-crunching boost of power) behind. They gain speed through curves one, two, three, gravity thrusting the sled down. Spectators spring onto their tiptoes; a kid whoops and punches the air as the sled barrels through curve six.

Olsen (top, right) consults his teammate, Evan Weinstock, before a run at the Lake Placid Olympic Sports Complex.

Joao Canziani

Half bent over, in helmets and matching skintight navy-blue suits, thirty-year-old Olsen—the gold-medalist push man turned pilot—and his teammates are nearly impossible to differentiate from each other. Together, the team looks more like a giant whooshing snap pea than a quartet of elite athletes. Bobsled is a balancing act, and shaving off a few hundredths of a second comes down to Olsen’s power, speed, and precision.

In his 2013 memoir, But Now I See, legendary bobsled driver and Olympic hero Steve Holcomb likened bobsled to ballet. It’s an apt analogy. These men could blend in on an NFL sideline, but they’re actually burly ballerinas, exploding off the starting block tiptoed in steel-plated shoes that flex like a leather slipper, and mirroring each other with near-perfect synchronicity.

Holcomb led the U.S. Men’s Bobsled Team to three Olympic medals, ten World Championships, sixty World Cup tour medals, and served as Olsen’s unofficial mentor. If things had gone according to plan, Holcomb would’ve been piloting down this slippery, fifteen-turn track. But in May 2017, Holcomb was found dead in his dorm room outside of Lake Placid, New York, upending U.S. Bobsled’s plans and expectations. Olsen was left to grieve his friend and advocate—and get back in the sled. With only a few short months to spare, he had to figure out not only how to lead a team he wasn’t supposed to be leading, but also how to find a way to the Olympic podium.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Spectators at the Lake Placid bobsled track wait for the next sled.

Joao Canziani

Bobsled might not seem as dangerous and difficult as it is. If you’re watching a race on TV, say, it could look as if there’s not much to it: What else is there to do besides jump in a sled on an ice-coated slide and let gravity take over?

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

But bobsled is wild. If you know nothing about the sport outside of the movie Cool Runnings, here’s how it works: In either the two-man or four-man race, one or three brakemen (or push men) push the 450-pound sled. The driver (also called the pilot) steers by tugging on D-rings, like taut sleigh reigns. Once they’re off, bobsled speeds can exceed ninety miles per hour, with each rider plastered to his seat by more G-forces than astronauts experience at takeoff. Every turn on the track is like getting kicked in the groin and chest while a truck sits on your head, Olsen told me. It’s almost like the nauseating pull of a roller-coaster loop, but 100 times more intense.

The International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation

The goal is to maintain fluidity, to not crash or fall over. The subtlest of movements can mean the difference between a gold medal and missing the podium entirely. If the driver catches a curve too late, or comes off early, the sled can flip and plummet down the track, ejecting the riders onto a sheet of ice that cheese-grates the skin.

And bobsled drivers barely get a chance to practice before competing, upping the stakes on the entire enterprise. There are only sixteen tracks in the world, each with its own set of curves, gradients, and conditions. So pilots have to memorize them, walking down a track to quickly learn its quirks before getting in maybe three runs prior to a major race. (Imagine if NASCAR drivers, jockeys, or speed skaters had less than five minutes on their tracks before go time.)

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Piloting requires not just skill but a hefty dose of intuition, since it’s impossible for a driver to see much more than a few feet in front of him in the twisting, thunderous tunnel of ice. It also demands the ability to mentally disconnect. It’s not about strategic thought, but about letting go, almost like getting lost, and somehow finding the right amount of control in a largely uncontrollable craft.

“Every run down the track is kind of like a car crash,” Olsen says. “Like an old car hitting a really long patch of ice.”

Joao Canziani

Who would want to repeatedly relive a car crash? As a job?

Olsen might not have dreamt of becoming a bobsled champion growing up (not many kids do), but he was built for it. Born to two competitive athletes—his dad played football and basketball, while his mom ran track—Olsen was raised in West Texas and immersed in the Texas faith of football. Early on, he showed a propensity for two traits bobsled coaches love: a hunger for speed and an utter lack of fear, no matter how turned around he might’ve been. At age four, says Olsen’s mom, Kim, he took off his bike’s training wheels so he could go faster. (He suffered his first concussion shortly after, when he flew over the handlebars and landed on his face; in sum, he’s had around ten.) As he grew up, he’d wander off aimlessly into the woods and fields around his home for hours, somehow always navigating his way back home. “He’d come back with scraped shins, dirt splotched across his face, bruised up, and mosquito bites covering every inch of him,” says Kim.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

When Olsen was ten, his football coaches told his parents that he showed boundless promise, thanks to his abnormal commitment to extra practice time and his untamed exuberance on the field. He went on to play football at the Air Force Academy, where he studied engineering, a dream asset for bobsled, since athletes are tasked with repairing their own sleds. But he didn’t stay long—“I wasn’t ready for that kind of structure”—and went back to Texas, where he worked multiple jobs and took engineering classes, unsure of what to do next. “He was sort of just…lost,” Kim says.

One day in 2007, Kim heard a radio ad calling for athletes with strength, speed, and a high vertical jump. “And something about bobsledding,” she says. “In San Antonio, of all places. I figured Justin had all those things, so I told him to go.”

Joao Canziani

Olsen and four other guys showed up and went through the paces. Team USA coaches invited him to travel to Lake Placid, New York, the headquarters of U.S. Bobsled, to be evaluated for the team. “It felt like it was right to at least give it a shot,” Olsen says. He was nineteen and broke, so he sold his motorcycle, stereo—anything he could find to pay for the plane ticket. “I thought he was out of his mind,” Kim recalls. But a few weeks later, after cutting it in early tryouts, he called home with news: He was moving to upstate New York.

The sliding track suited him. He craved its explosive starts and the adrenaline of winning by .01 seconds. “He didn’t mind that when you’re making it in bobsled, you end up riding in a sled that gets flipped over by amateur drivers,” says Brian Shimer, U.S. Bobsled’s head coach. Physically, Olsen was a near-perfect push man: tall, with broad shoulders and knotty legs that could lift the entire U.S. figure-skating team.

About a month into his new career, he met Holcomb, the centerpiece of the U.S.’s Men’s Bobsled Team. (“The best,” says Olsen.) All of the new push athletes wanted to be on the ten-year veteran’s sled, USA-1; Olsen surprised everyone when, in his second season, he landed the coveted spot and started pushing for Holcomb in the two-man. “He called me and the first thing he said was, ‘I’m on Steve’s sled!” Kim says.

Over the next eight years, Olsen traveled the circuit with his team, racing in both the two-man and the four-man with Holcomb, hanging out with him in training rooms and hotel lobbies. “Justin was the man-child on the team, and definitely the entertainment,” says retired push man Steve Mesler, a veteran of Holcomb’s four-man sled. Holcomb was the pro who “kept to himself,” says Olsen. He’d always been the quiet teammate, and for good reasons.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

A stoic older-brother figure, Holcomb was an unlikely Olympic champion with a complicated backstory. In 2006, just as he started to succeed on the track, he noticed his eyesight worsening. He told no one. Doctors diagnosed him with keratoconus, a degenerative eye disease that distorts the cornea, and warned him that total blindness was imminent. He kept driving—bobsled is the rare sport where one can get away with less-than-20/20 vision—but the pressure of battling the disease, and his decision to keep it secret, isolated him from the team. He suffered from depression and, in 2007, washed down seventy-three sleeping pills with a bottle of Jack Daniel’s in a suicide attempt. A few months later, upon his coach’s urging, Holcomb received an experimental surgery—a surgery subsequently named Holcomb C3-R—to correct his vision.

After winning the gold medal in Vancouver. L-R: Curt Tomasevicz, Steve Mesler, Olsen and Holcomb.

Getty Images

Holcomb returned to driving just as Olsen started to shine as one of the team’s best push men. The legendary driver remained reclusive, but Olsen had a penchant for opening him up—cracking jokes about the young upstart one day beating the older vet, peppering Holcomb with questions about what to look for during walks down the track, indoctrinating him into Olsen’s not-so-secret Swiftie side. “Steve walked in on me once in my hotel room,” says Olsen. “He was like, ‘Dude, you’re this big-ass guy, in tiny little underwear, listening to Taylor Swift.’ I said, ‘I don’t know, man. It just makes me feel good.’” The duo often appeared together doing “the Holcy Dance”—a kind of restrained shuffle of Holcomb’s that became a team joke as they competed around the globe.

Together, they medaled in two World Cup races and won the 2009 World Championships in the four-man. In 2010, as they headed into Vancouver’s Olympics, their four-man sled, dubbed the Night Train, was number one in the world, and for the first time in sixty-two years, Americans won the gold. Along with their teammates Steve Mesler and Curt Tomasevicz, Holcomb and Olsen landed on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

L-R: Holcomb, Olsen, Mesler, and Tomasevicz.

Getty Images

Throughout, commentators spoke about Olsen and his meteoric rise with astonishment usually reserved for kid prodigies. Bobsledders typically either push or drive; switching positions is rare, especially after reaching the pinnacle of the sport as a push man. “It’s very difficult to be a brakeman, then pick up the skills to drive,” says head coach Shimer, a five-time Olympian himself. But Olsen was different. He’d had a great mentor to study, the best in the world. After Vancouver, he thought, Maybe my time as a brakeman is done. “My coaches said, ‘You’re a great brakeman, and you’re young; we’ve got to get you in the driver’s seat,’” he says.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

He split his time between pushing for Holcomb and feeling out driving. “In driving, if you’re not really ready for what you’re about to see [on the track], that’s when you can make mistakes,” Olsen says. And he did make mistakes, a lot of them, but he knew what a winning drive should feel like. “I was ready for whatever challenges driving came with. Learning to drive new tracks and managing stress, I was fine with that.”

“For me, [he] was going to be our next Steve Holcomb,” says Shimer. “Our next franchise. The program was going to be built around Justin Olsen.”

Last March, Holcomb and Olsen were in Pyeongchang for a World Cup race—the first on the new track built for the 2018 Games. They strategized how best to run the track’s sixteen curves. Curve two was particularly tricky. On their second day, while Holcomb was still bumping the wall, Olsen ran it clean and explained to Holcomb what he’d done. Advising his mentor felt new, and weird.

Afterward, they sat together and talked. “He kind of caught me off guard,” Olsen recalls. Whatever it is that makes bobsled pilots great—that intangible quality drivers and coaches can’t exactly define—Holcomb said he thought Olsen had it. “Pilot instincts, I guess,” says Olsen. “It was the first time he’d ever said anything to me like that.” Olsen, Holcomb said, was going to be a phenomenal driver. “Well shit, thanks,” Olsen replied, humbled.

Olsen and Holcomb at a New York Rangers hockey game following the Vancouver Olympics.

Getty Images

Two months later, on a humid and cloudy May morning at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Lake Placid, where dozens of winter Olympians live year-round, frantic texts from his teammates suddenly popped up on Olsen’s phone: I’m worried. I haven’t heard from Steve. Have you seen him?

More texts rang out. I’m just really worried about Steve. I have a really bad feeling. Olsen asked them to call the building’s manager to open Holcomb’s door, on the opposite side of the dorm-style building from him. “I don’t mind if we barge into Steve’s room and he yells at us,” he texted back. “I’ve done it before.” He dressed quickly, then heard furious knocks at his door. Olsen opened it to find the manager of Lake Placid’s training center, one of Steve’s closest friends, winded and panicking. “It’s bad, it’s really, really…”

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Barefoot, Olsen ran through the halls to the opposite wing of the building and found two of his teammates hugging outside Holcomb’s door, tears streaming down their faces. “Somebody tell me what’s happening,” Olsen said. “What did you see?”

Holcomb celebrates a four-man run in Koenigssee, Germany in January 2017.

Getty Images

“He’s dead,” one of them mumbled. Olsen didn’t believe it at first. “Did you check his pulse?” Olsen asked. The door was cracked. “Yeah, we did. He’s not moving,” they said. Holcomb, only thirty-seven, had died in his sleep. (An autopsy later found excess amounts of sleeping pills and alcohol in his system; the coroner ruled it an accidental death.)

Olsen went back to his room before the emergency medical technicians arrived. “I just didn’t want to see my close friend like that. I was shocked, but I wasn’t completely frozen,” he says. He had calls to make, to coaches and the CEO of U.S. Bobsled.

When he hung up his last call, Olsen felt his tempered resolve give way to a familiar dread—shortness of breath, nausea, and panic, as he experienced a kind of déjà vu from two years prior, when his father had died from a sudden heart attack. Back then, with his dad, he tried not to think about it and just kept racing. He’d deal with it later, he told himself. But with Holcomb’s death, “I knew I couldn’t act how I did with my dad,” says Olsen. “I knew I needed to be here this time…I knew that I needed people around me, and that people needed me.”

“Olsen was a rock,” says Holcomb’s best friend, Katie Uhlaender. “He helped me sort through the chaos.” He’d lost the person who represented his immediate future; the person who told him, You’re next, and was supposed to lead him there. “You’re not prepared to lose someone close until you lose somebody close,” says Olsen. “No one can replace Steve. I won’t.” He couldn’t breathe well at times, but he adopted the role of a leader, a role he knew the team needed.

Joao Canziani

“Justin stepped up. He knew how important Steve was,” says Shimer. “Steve Holcomb was the soul of this team. He was one of the best drivers in the world. The prospect of the two of them driving at the Games—that’s tough to walk away from.”

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

After the memorial service in Lake Placid, Olsen knew he had to get back to training for Pyeongchang. Training was relatively simple in the off-season—a lot of cardio and weights and making sure you don’t get hurt. Getting back in the sled was not.

Joao Canziani

Four months before the Games, the team gathered, as they always did, for the first run at the Lake Placid track. For a decade, Holcomb had taken the first run. “This year, my coach looked at me and said, ‘Olsen, you’re going to be the first one down the hill.’ That was my oh shit moment.”

For a second, he felt physically unable to take a step forward. “I had to,” Olsen says. “Even though I didn’t feel like [Holcomb] and I were done when he passed away—this is still my sport, even though it’s not the same.”

Holcomb’s death doesn’t make it harder to drive, Olsen says. What’s difficult are the waves of yearning for more time spent walking down the track, knowing that Holcomb would do anything to help Olsen improve. He’s motivated by his memory, by trying to find what else of Holcomb’s he can carry with him, and by all the things Holcomb taught him—like how reveling in achievement isn’t as important as the opportunity to have it.

“All you really have is what’s right in front of you,” Olsen says. You travel full speed, falling into a blinding, white blur where unexpected things happen—where, if you’re going fast enough, you can soar upside down and come back again, seamlessly.

After his November run in Park City, Olsen competed in five more World Cup events, ending up as the top American finisher in the last two races before the Games. It’s the position Holcomb would’ve been in, the one with all the hopes and expectations for the medal stand.

This week, after the ceremonies and the practice runs in Pyeongchang have passed, Olsen will arrive at the track again. He’ll close his eyes at the top of the hill and find a dark kernel of stillness. In the symphony of low hums coming from somewhere down the ice, he’ll summon his previous runs. He’ll think of curve two, and Holcomb’s advice about curve nine will reverberate in his head.

He’ll open his eyes at the start and tap the sled to signal to his teammates that he’s ready. He’ll jump in and let go. The world will turn quiet for fifty seconds in a sea of blurry white. And, hopefully, he’ll lift his gaze and punch his fist in the air because his start was perfect and he’d figured out the rest.

Photography by João Canziani • Videography by Matthew Troy •

Edited by Whitney Joiner

Source link

0 notes