#Shlomo Rechnitz

Text

Shlomo Rechnitz nursing home suit over COVID deaths reflects ‘broken state licensing’

Johanna Trenerry of Happy Valley holds a photograph of herself with her husband, Art Trenerry, who died last year of COVID-19 while staying at Windsor Redding Care Center. His family members, including Johanna, are named as plaintiffs in a lawsuit against the facility. Photo by Matt Bates for CalMatters

IN SUMMARY

A lawsuit describes nursing home magnate Shlomo Rechnitz and his companies as the “unlicensed owner-operator” of a troubled Redding facility.

The state’s largest nursing home owner, Shlomo Rechnitz, is facing a lawsuit alleging that one of his homes is responsible for the COVID-related deaths of some 24 elderly and dependent residents.

The catch? Five years ago, the state denied Rechnitz and his companies a license to operate the place, the state’s own records show.

The case brought against Rechnitz, his companies and the home itself, Windsor Redding Care Center, is yet another footnote in an ongoing nursing home licensing saga documented in a CalMatters investigation last spring.

That investigation revealed an opaque and confusing state licensing process frequently marred by indecision and delays. CalMatters found that the California Department of Public Health has allowed Rechnitz to operate many skilled nursing facilities for years through a web of companies as their license applications languish in “pending” status — or are outright denied.

The lawsuit — which includes a total of 46 plaintiffs, including 14 deceased residents and 32 family members — specifically calls out Rechnitz and his management companies as being an “unlicensed owner-operator” of the skilled nursing facility. The plaintiffs also are suing the previous owners, whose names and companies remain on the license.

Family members of residents who died as a result of a COVID-19 outbreak last fall are suing the facility for elder neglect and abuse, alleging that Windsor Redding forced employees to come into work while symptomatic with the virus, triggering the outbreak.

The complaint further alleges that dozens of residents who fell ill were left isolated and neglected due to “extreme understaffing.” One nurse told state inspectors that she alone had to pass out medications to 27 COVID-positive patients, meaning the medications were often late, according to an Oct. 21, 2020, inspection report, also cited in the lawsuit. Another nurse told them that nurses on the COVID unit, or “Red Zone,” were “stressed, overloaded and tapped out” and unable to take breaks, the report said.

The complaint lists 142 violations substantiated by investigators including neglect, abuse, staffing and infection control issues between January 2018 and June 2021. In November 2020, the federal government fined the facility $152,000 as a result of the inspections.

A ‘broken’ licensing system

Democratic Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi of Los Angeles said the lawsuit against the Redding facility, located 160 miles north of Sacramento, “clearly provides Exhibit A of the broken state licensing system for nursing homes.”

“The fact that this facility had its license application denied and yet they continued to operate during this pandemic, which unfortunately led to an alleged 24 deaths from COVID, highlights the urgent need for the state to fix its broken licensing system,” he said.

On Tuesday, the Assembly Health Committee will hold an informational hearing to discuss problems with nursing home oversight and licensing in the state.

“They know this operator is running the facility, and they’re not doing anything about it. In a sense, the state could be co-defendants in this case.”

Rechnitz, a Los Angeles entrepreneur, was in his mid-30s when he began buying nursing homes 15 years ago. He and his companies, including Brius Healthcare, have acquired at least 81 facilities around California, making him the state’s biggest for-profit nursing home owner.

Rechnitz and his companies operate more than a quarter of those facilities despite the fact that the California Department of Public Health has not approved — or has outright rejected — their licensing applications, according to state records. In the case of five “Windsor” facilities, including Windsor Redding, Rechnitz and his companies continue to run them after the state’s license denial. The previous owners’ companies, affiliated with the Windsor brand, are still listed in state records as the official license-holders.

Mark Johnson, an attorney who represents Rechnitz and Brius, said in an emailed statement that he could not comment on pending litigation except to say that: “The facility vehemently disagrees with the allegations and it intends to defend the action vigorously.”

Johnson has previously declined to answer detailed questions about the licensing issues. But he has expressed frustration in emailed statements to CalMatters about the state’s inconsistent approach to Brius homes — approving some, denying others, and leaving still others stuck in pending status.

The death of Art Trenerry

Art Trenerry arrived at Windsor Redding on Aug. 6, 2020, after suffering a stroke, his family and attorney say. Several of Trenerry’s family members are named as plaintiffs in the lawsuit.

Visitors weren’t allowed inside at the time, they told CalMatters. Instead, Johanna, his wife of 60 years, and their children would visit outside the window, said one of their daughters, Nancy Hearden, in an interview. Sometimes the facility would wheel the wrong person out, she said.

Johanna said she would ask nurses to hold the phone to her 82-year-old husband’s ear so she could tell him “Hi Dad, I love you.”

His daughters called twice a day to check on him, growing concerned by their perception that “things aren’t right,” Hearden said. They began looking to move him to a new facility, or to bring him home, she said.

Hearden said she called in a complaint about the care her father received to Shasta County’s public health department on April 20, 2021. “Their response to me was, ‘they’re complying now,'” she said.

Hearden said she had not known who owned the facility when her father arrived there. The state denied Rechnitz licenses to operate Windsor Redding and four other facilities in July 2016, citing the poor track records of many facilities “owned, managed, or operated, either directly or indirectly, by the applicant,” according to 22-page denial letters addressed to Rechnitz.

Two departments within state government record Rechnitz’ relationship to the Redding facility differently. Rechnitz is listed as the owner of Windsor Redding in cost reports filed with the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development in 2020. But his name is not on the California Department of Public Health’s consumer website, Cal Health Find, which identifies the facility’s owner/operator as Lee Samson, Lawrence Feigen and two limited liability companies with the Windsor brand. Windsor still operates nursing homes in California and Arizona, according to its website.

The lawsuit, filed last month in Shasta County Superior Court, also alleges that Rechnitz and his “management operating companies” circumvented the state’s denial by creating a “joint venture” with Samson and a limited liability company affiliated with S&F Management.

S&F is a West Hollywood-based company that provides “professional consulting services to Windsor facilities,” Todd Andrews, senior vice president of S&F Management Co., told CalMatters in March. When asked about the lawsuit last week, Andrews said that his company and its president and CEO, Lee Samson — also named as defendants in the complaint — have had no day-to-day involvement with the facility. He said the state “has not transferred the license in over seven years,” despite repeated appeals, so Windsor remains the licensee.

A spokesperson for the California Department of Public Health declined to comment on the case because it is pending litigation.

Nursing home oversight in legislative crosshairs

Assemblymember Muratsuchi authored a bill earlier this year that would forbid the use of management agreements to “circumvent state licensure requirements” and would require owners and operators to get approval from the California Department of Public Health before acquiring, operating or managing a nursing home.

Long before COVID-19, Windsor Redding had a history of care problems. Given that, the complaint says, “it was foreseeable that Defendants would continue to neglect and harm more residents during the pandemic.”

In August 2020, state inspectors cited the facility for admitting patients who were negative for COVID-19 into rooms with residents who were positive for the virus, or had been exposed.

COVID outbreak sweeps through home

By the next month, the facility had an outbreak — 60 of the 83 residents contracted the virus, and “approximately 24” passed away from complications related to COVID-19, the complaint states. (The state identified 23 COVID-related deaths at the home last fall and winter.)

In September 2020, the California Department of Public Health conducted an inspection of the facility and declared an “immediate jeopardy,” the level of deficiency reserved for the most egregious incidents in nursing homes that could cause serious injury or death.

Among the inspection’s findings: the facility had punitive sick leave policies. Two staff members reported being told to come into work despite having symptoms of COVID-19, including “body aches, chills, sweats and respiratory symptoms” for one and “loss of taste, lethargy, and cough” for the other, according to a Sept. 25, 2020, inspection report. Both eventually tested positive.

The complaint alleges, further, that the defendants have a “general business practice” of understaffing the facility.

“It makes dying alone even lonelier,” said Wendy York, a Sacramento attorney specializing in nursing home abuse whose firm is among three representing the families. “My heart gets heavy when I think of them in this unit, in this environment.”

Tony Chicotel, staff attorney for California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, said he holds the state partly to account for the outbreak.

“They know this operator is running the facility, and they’re not doing anything about it,” he said. “In a sense, the state could be co-defendants in this case.”

Trenerry family say its goodbyes

The last time Johanna Trenerry was able to see her husband, Art, was the night of Sept. 25, 2020, after he tested positive for COVID. She and some of her children were allotted 15 minutes each to see him. During those minutes, Trenerry sat next to her husband, holding his hand. Right before she left, she raised her face shield and kissed him. He died a week and a half later.

Johanna Trenerry is Catholic, and believes that Art is with God now, and that they’re both keeping an eye on her. Ever since the couple met as 16-year-olds on a blind date, Art had taken care of her, always supporting her “crazy ideas.” She told him she wanted a big family, a farm and a two-story house. “Ok, hon, whatever you want, you can have,” he said.

He worked as a stationary engineer, doing maintenance at the local hospital in Redding, and served as a volunteer firefighter and on the local water board. They raised eight children together on a 14-acre farm in Happy Valley, a small community outside town. His family describes him as quiet, but funny, always ready to help a neighbor and so devoted to his grandchildren that he built them a miniature railroad track on the property.

When a friend down the street said that her own husband was unwell, Johanna didn’t mince words.

“Don’t send him to a rest home,” she told her friend. “He’ll die there.”

0 notes

Text

Troubled Nursing Home Chain Owner Shlomo Rechnitz Gets New Licenses Just Before State Reforms Take Effect

The state is moving forward with licensing two dozen nursing homes whose primary owner’s companies have a lengthy track record of problems – as uncovered by a CalMatters investigation – despite a new law designed to provide better oversight of the facilities.

The nursing homes in question are owned by Los Angeles businessman Shlomo Rechnitz, who owns dozens of California facilities through a web of companies, including Humboldt County's four primary skilled nursing facilities.

One of his main companies, Brius Healthcare, has been scrutinized for poor quality care and inadequate staffing, according to federal and state inspection reports, plaintiffs’ attorneys and press accounts. By 2015, government regulators decertified or threatened to decertify three of Rechnitz’s companies’ California nursing homes, a rare penalty that strips facilities of crucial Medicare and Medi-Cal funding.

One of those facilities, Wish-I-Ah Healthcare & Wellness Centre near Fresno, was closed following the death of a 75-year-old resident from a blood infection after staff left behind in her body a foam sponge used in dressing her mastectomy wound. Investigators also found toilets brimming with fecal matter and other serious problems, according to the state’s accusation.

The State Auditor’s office in a May 2018 report spotlighted Brius for its higher rate of federal deficiencies and state citations, compared to the rest of the industry in the state.

It was via bankruptcy court that Rechnitz scooped up 18 Country Villa-branded nursing homes in 2014. Per state law, he then filed change-of-ownership applications seeking licenses to run those homes. The state didn’t approve or deny them, instead leaving them pending. In the meantime, Rechnitz continued to run the nursing homes for years without a formal license in his name – which isn’t technically illegal.

A new law was supposed to close that loophole. But that law, co-authored by Democratic Assemblymembers Al Muratsuchi of Los Angeles and Jim Wood of Santa Rosa, doesn’t go into effect until July 1 — and it focuses on new license applications, rather than those that have been operating in the legal gray area for years.

The California Department of Public Health, which oversees the state’s nursing homes, defended the new licensing settlement with Rechnitz, which includes tools for the state to monitor the nursing homes’ performance. The department noted the settlement allows the nursing homes to continue operating, instead of closing and forcing hundreds of residents from their homes.

“This settlement resolves longstanding issues we have had with this provider and provides our department stronger enforcement tools to ensure the provider is delivering reasonable and appropriate care to its residents,” Dr. Tomás Aragón, director of the Department of Public Health, said in an emailed statement. “With this settlement, we will continue to monitor the facilities involved with a focus on maintaining that level of care.”

Under the settlement announced this week, the state health department agreed to approve license applications for 24 skilled nursing facilities owned by Rechnitz – once the department receives all necessary documents to complete the process.

The settlement includes some oversight provisions, including a two-year monitoring period. The health department is to meet with each facility every six months to review the quality of care residents are receiving, and each facility is to provide a slew of documents before the meetings. Deficiencies in care are to result in heightened oversight, including daily phone calls. Failing to comply with those parameters is to result in a fine of $10,000 per failure.

An attorney representing Rechnitz’s company Brius did not respond to a phone call or an emailed request for comment.

“We think this is a message to residents of nursing homes in California that their welfare just isn’t all that concerning to the state.”

Tony Chicotel, California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform

Tony Chicotel, a staff attorney for California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, called the state’s move to license Rechnitz’s nursing homes “sad.”

“There’s been longstanding, systematic problems in nursing homes run by this chain,” he said. “We think this is a message to residents of nursing homes in California that their welfare just isn’t all that concerning to the state.”

Not all of Rechnitz’s applications had been left pending – some were denied outright. In denying his licensing application for Windsor Healthcare Center of Oakland in 2016, the Department of Public Health said staff at the facility neglected to treat the skin ulcers and pain of six different residents — including a paralyzed resident who was left covered in feces and then hospitalized for sepsis.

That facility is now one of the 24 the state is moving toward licensing under the new settlement. The two-dozen facilities also include 13 of the 18 Country Villa properties Rechnitz purchased in 2014.

Another one of Rechnitz’s nursing homes was in hot water recently. Alta Vista Healthcare & Wellness Centre in Riverside, owned by Rechnitz, and its management company, Rockport Healthcare Services, agreed to pay the state and federal government some $3.8 million over allegations they provided kickbacks to doctors. According to the U.S. Justice Department, Alta Vista gave doctors extravagant gifts – including expensive dinners, limousine rides and massages – in exchange for referring patients to their nursing home between 2009 and 2019.

That facility is not included in the new licensing agreement.

Chicotel said he’s “disappointed but not surprised” the state is moving to license Rechnitz’s facilities. It was clear that the law taking effect July 1, which he opposed because he said it lacked teeth, would not take existing facilities away from bad operators, he said.

Assemblymember Wood’s spokesperson, Cathy Mudge, said he was not aware of the settlement and would not be able to comment on it yet. “This is an important issue to him and he will be asking CDPH for more information,” she said in an email.

Assemblymember Muratsuchi’s office did not respond to an email seeking an interview.

The new law still has value going forward because it will apply to new cases, said Dr. Michael Wasserman, a geriatrician and chair of public policy for the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine.

“I think (it) was meant to keep the type of licensing issues that have occurred in the past from ever happening again,” he said.

Author: Celia Hansen

0 notes

Text

Who is Shlomo Rechnitz?

Shlomo Rechnitz is the Los Angeles-based, multi-billionaire owner of Brius, the largest nursing home company in California. In 1998, Rechnitz began his business career by selling supplies—such as latex gloves, adult diapers, and wheelchairs—to nursing homes with his twin brother, Steve. Together, they founded and operated TwinMed, LLC, and have grown it into a nation-wide distributor of medical supplies and services.

Business Holdings

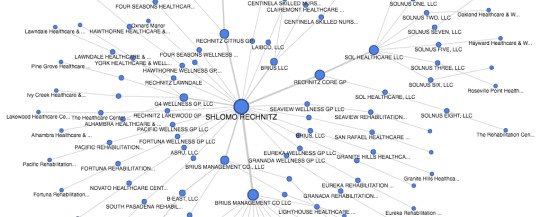

Rechnitz reportedly controls his California nursing homes through a web of 130 companies, according to the Sacramento Bee. He has an ownership stake in many other companies, including a pharmaceutical company, two medical supply corporations, and a management services business.

Wealth

Rechnitz’ total wealth is not publicly available, although records from the Securities and Exchange Commission, the IRS, and other government agencies indicate he controls millions of dollars of assets and cash. As part of a bidding process to acquire one long-term care facility, Brius disclosed to the California Attorney General that it took in profits of $77 million in 2013.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rechnitz is also the owner of Brius Healthcare Services, the largest for-profit nursing home provider in California. Rechnitz runs over 80 facilities in California, Nevada, and Texas.

0 notes

Text

Nursing home, management reach $3.8M settlement with feds in kickbacks case

A California skilled nursing facility run by the state’s largest nursing home owner has, in conjunction with its management firm, agreed to pay $3.8 million to settle kickback allegations brought by a whistleblower.

Alta Vista Healthcare & Wellness Centre in Riverside, CA, and Rockport Healthcare Services faced False Claims Act charges of paying physicians to send them more patient referrals over an 11-year period, the Department of Justice announced late Wednesday.

The settlement amount was negotiated based on Alta Vista’s and Rockport’s “lack of ability to pay,” the government said.

It alleged that from 2009 through 2019, Alta Vista, “under the direction and control of Rockport,” gave some physicians gifts including expensive dinners, golf trips, massages, tablets, and gift cards worth up to $1,000.

Alta Vista also paid the same physicians monthly stipends of $2,500 to $4,000, “purportedly” for their services as medical directors, a press release on the case said, noting that “at least one purpose of these gifts and payments was to induce these physicians to refer patients.”

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services records indicate Alta Vista has been at least partially owned by Shlomo Rechnitz since 2019. He has held operational or managerial control of the 99-bed facility since 2009.

Rechnitz or his wife Tamar are listed as owners of 118 nursing homes in a CMS database; it’s unclear if all of those are in California. A company that Rechnitz owns, Brius Healthcare, reportedly operates more than 80 nursing homes in the state, making it the largest provider there.

He is a controversial owner, having been targeted in several lawsuits and state actions. A similar 2019 False Claims suit alleges Alta Vista, Rechnitz, Brius and Rockport paid cash kickbacks to employees who recruited skilled patients.

In the case resolved this week, the government said Alta Vista and Rockport’s actions resulted in false claims to Medicare and California’s Medicaid programs, the latter of which is jointly funded by the federal government and California. Under the settlement, they will pay $3,228,300 to the United States and $596,700 to California.

“Decisions that affect patient health should be made solely on the basis of a patient’s best interest,” said California Attorney General Rob Bonta. “When a healthcare company cheats and offers kickbacks to gain an unfair advantage, it jeopardizes the health and wellbeing of those who rely on its services. These illegal schemes also make public services and programs costlier, and ultimately waste valuable taxpayer dollars.”

The complaint being resolved began in 2015, when a former Alta Vista accounting employee brought her complaints in a qui tam suit on behalf of the government. That employee, Neyirys Orozco, will receive $581,094 as her share of the federal government’s recovery.

In addition to resolving their False Claims Act liability, Alta Vista and Rockport also entered into a five-year Corporate Integrity Agreement with the HHS-OIG which requires, among other compliance obligations, an Independent Review Organization’s review of Alta Vista’s and Rockport’s physician relationships.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shlomo Rechnitz nursing home suit over COVID deaths reflects ‘broken state licensing’

The state’s largest nursing home owner, Shlomo Rechnitz, is facing a lawsuit alleging that one of his homes is responsible for the COVID-related deaths of some 24 elderly and dependent residents.

The catch? Five years ago, the state denied Rechnitz and his companies a license to operate the place, the state’s own records show.

The case brought against Rechnitz, his companies and the home itself, Windsor Redding Care Center, is yet another footnote in an ongoing nursing home licensing saga documented in a last spring.

That investigation revealed an opaque and confusing state licensing process frequently marred by indecision and delays. We found that the California Department of Public Health has allowed Rechnitz to operate many skilled nursing facilities for years through a web of companies as their license applications languish in “pending” status — or are outright denied.

The lawsuit — which includes a total of 46 plaintiffs, including 14 deceased residents and 32 family members — specifically calls out Rechnitz and his management companies as being an “unlicensed owner-operator” of the skilled nursing facility. The plaintiffs also are suing the previous owners, whose names and companies remain on the license.

Family members of residents who died as a result of a COVID-19 outbreak last fall are suing the facility for elder neglect and abuse, alleging that Windsor Redding forced employees to come into work while symptomatic with the virus, triggering the outbreak.

The complaint further alleges that dozens of residents who fell ill were left isolated and neglected due to “extreme understaffing.” One nurse told state inspectors that she alone had to pass out medications to 27 COVID-positive patients, meaning the medications were often late, according to an Oct. 21, 2020, inspection report, also cited in the lawsuit. Another nurse told them that nurses on the COVID unit, or “Red Zone,” were “stressed, overloaded and tapped out” and unable to take breaks, the report said.

The complaint lists 142 violations substantiated by investigators including neglect, abuse, staffing and infection control issues between January 2018 and June 2021. In November 2020, the federal government fined the facility $152,000 as a result of the inspections.

A ‘broken’ licensing system

Democratic Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi of Los Angeles said the lawsuit against the Redding facility, located 160 miles north of Sacramento, “clearly provides Exhibit A of the broken state licensing system for nursing homes.”

“The fact that this facility had its license application denied and yet they continued to operate during this pandemic, which unfortunately led to an alleged 24 deaths from COVID, highlights the urgent need for the state to fix its broken licensing system,” he said.

On Tuesday, the Assembly Health Committee will hold an informational hearing to discuss problems with nursing home oversight and licensing in the state.

Rechnitz, a Los Angeles entrepreneur, was in his mid-30s when he began buying nursing homes 15 years ago. He and his companies, including Brius Healthcare, have acquired at least 81 facilities around California, making him the state’s biggest for-profit nursing home owner.

Rechnitz and his companies operate more than a quarter of those facilities despite the fact that the California Department of Public Health has not approved — or has outright rejected — their licensing applications, according to state records. In the case of five “Windsor” facilities, including Windsor Redding, Rechnitz and his companies continue to run them after the state’s license denial. The previous owners’ companies, affiliated with the Windsor brand, are still listed in state records as the official license-holders.

Mark Johnson, an attorney who represents Rechnitz and Brius, said in an emailed statement that he could not comment on pending litigation except to say that: “The facility vehemently disagrees with the allegations and it intends to defend the action vigorously.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Troubled Nursing Home Chain Owner Shlomo Rechnitz Gets New Licenses Just Before State Reforms Take Effect

The state is moving forward with licensing two dozen nursing homes whose primary owner’s companies have a lengthy track record of problems – as uncovered by a CalMatters investigation – despite a new law designed to provide better oversight of the facilities.

The nursing homes in question are owned by Los Angeles businessman Shlomo Rechnitz, who owns dozens of California facilities through a web of companies, including Humboldt County's four primary skilled nursing facilities.

One of his main companies, Brius Healthcare, has been scrutinized for poor quality care and inadequate staffing, according to federal and state inspection reports, plaintiffs’ attorneys and press accounts. By 2015, government regulators decertified or threatened to decertify three of Rechnitz’s companies’ California nursing homes, a rare penalty that strips facilities of crucial Medicare and Medi-Cal funding.

One of those facilities, Wish-I-Ah Healthcare & Wellness Centre near Fresno, was closed following the death of a 75-year-old resident from a blood infection after staff left behind in her body a foam sponge used in dressing her mastectomy wound. Investigators also found toilets brimming with fecal matter and other serious problems, according to the state’s accusation.

The State Auditor’s office in a May 2018 report spotlighted Brius for its higher rate of federal deficiencies and state citations, compared to the rest of the industry in the state.

It was via bankruptcy court that Rechnitz scooped up 18 Country Villa-branded nursing homes in 2014. Per state law, he then filed change-of-ownership applications seeking licenses to run those homes. The state didn’t approve or deny them, instead leaving them pending. In the meantime, Rechnitz continued to run the nursing homes for years without a formal license in his name – which isn’t technically illegal.

A new law was supposed to close that loophole. But that law, co-authored by Democratic Assemblymembers Al Muratsuchi of Los Angeles and Jim Wood of Santa Rosa, doesn’t go into effect until July 1 — and it focuses on new license applications, rather than those that have been operating in the legal gray area for years.

The California Department of Public Health, which oversees the state’s nursing homes, defended the new licensing settlement with Rechnitz, which includes tools for the state to monitor the nursing homes’ performance. The department noted the settlement allows the nursing homes to continue operating, instead of closing and forcing hundreds of residents from their homes.

“This settlement resolves longstanding issues we have had with this provider and provides our department stronger enforcement tools to ensure the provider is delivering reasonable and appropriate care to its residents,” Dr. Tomás Aragón, director of the Department of Public Health, said in an emailed statement. “With this settlement, we will continue to monitor the facilities involved with a focus on maintaining that level of care.”

Under the settlement announced this week, the state health department agreed to approve license applications for 24 skilled nursing facilities owned by Rechnitz – once the department receives all necessary documents to complete the process.

The settlement includes some oversight provisions, including a two-year monitoring period. The health department is to meet with each facility every six months to review the quality of care residents are receiving, and each facility is to provide a slew of documents before the meetings. Deficiencies in care are to result in heightened oversight, including daily phone calls. Failing to comply with those parameters is to result in a fine of $10,000 per failure.

An attorney representing Rechnitz’s company Brius did not respond to a phone call or an emailed request for comment.

“We think this is a message to residents of nursing homes in California that their welfare just isn’t all that concerning to the state.”

Tony Chicotel, California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform

Tony Chicotel, a staff attorney for California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, called the state’s move to license Rechnitz’s nursing homes “sad.”

“There’s been longstanding, systematic problems in nursing homes run by this chain,” he said. “We think this is a message to residents of nursing homes in California that their welfare just isn’t all that concerning to the state.”

Not all of Rechnitz’s applications had been left pending – some were denied outright. In denying his licensing application for Windsor Healthcare Center of Oakland in 2016, the Department of Public Health said staff at the facility neglected to treat the skin ulcers and pain of six different residents — including a paralyzed resident who was left covered in feces and then hospitalized for sepsis.

That facility is now one of the 24 the state is moving toward licensing under the new settlement. The two-dozen facilities also include 13 of the 18 Country Villa properties Rechnitz purchased in 2014.

Another one of Rechnitz’s nursing homes was in hot water recently. Alta Vista Healthcare & Wellness Centre in Riverside, owned by Rechnitz, and its management company, Rockport Healthcare Services, agreed to pay the state and federal government some $3.8 million over allegations they provided kickbacks to doctors. According to the U.S. Justice Department, Alta Vista gave doctors extravagant gifts – including expensive dinners, limousine rides and massages – in exchange for referring patients to their nursing home between 2009 and 2019.

That facility is not included in the new licensing agreement.

Chicotel said he’s “disappointed but not surprised” the state is moving to license Rechnitz’s facilities. It was clear that the law taking effect July 1, which he opposed because he said it lacked teeth, would not take existing facilities away from bad operators, he said.

Assemblymember Wood’s spokesperson, Cathy Mudge, said he was not aware of the settlement and would not be able to comment on it yet. “This is an important issue to him and he will be asking CDPH for more information,” she said in an email.

Assemblymember Muratsuchi’s office did not respond to an email seeking an interview.

The new law still has value going forward because it will apply to new cases, said Dr. Michael Wasserman, a geriatrician and chair of public policy for the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine.

“I think (it) was meant to keep the type of licensing issues that have occurred in the past from ever happening again,” he said.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Creating a Successful Business

Creating a Successful Business

Creating a successful business is no easy feat. It requires a lot of hard work, dedication, and the ability to adapt to changing market conditions. In this blog post, we will explore some of the key factors that contribute to creating a successful business and provide tips on how to get started.

Read To Learn More: Shlomo Rechnitz

Develop a Clear Vision

A clear…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Shlomo Rechnitz: Importance of Charity

Shlomo Rechnitz: Importance of Charity

Shlomo Rechnitz: Importance of Charity

Donating to Charity and Why it’s important by Shlomo Rechnitz. There are many ways to participate in the work of the charity. Not only can charity work come in a variety of kinds of ways to utilize your funds. However, it could also help good causes in communities around you or further.

What kind of work for charity Can I do?

If you’re not sure how to begin…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#hocmedia#hocmultimedia#hocmediaproduction#khoahocmedia#khoahocmultimedia#hocmediaodau#hocmultimediaodau#huongnghiepaau#hnaau#sanxuattruyenthong#quanlysanxuattruyenthong

0 notes

Photo

Brius nursing homes in California

Shlomo Rechnitz is the Los Angeles-based, multi-billionaire owner of Brius, the largest nursing home company in California.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Profit Scheme Amasses Millions for California Nursing Home Chain Brius Healthcare

California’s largest for-profit nursing home chain, Brius Healthcare, has fallen under scrutiny for its financial practices following an investigation into why its facilities scored poorly on inspections of staffing, overall care, and resident health and wellbeing despite Brius’ seemingly immense funding. The primary owner of Brius Healthcare, Shlomo Rechnitz, began the nursing home conglomerate with a single Los Angeles facility in 2006; since that time, the operation has grown to more than 80 facilities across the state of California. As of 2018, Brius Healthcare received nearly one billion in funding from Medicare and Medicaid alone.

Channeling Money Through Nursing Home Companies

The crux behind the profit setup lies in “related parties,” or companies that nursing home providers or their families own in whole or in part. The nursing home uses operating funds to pay these related parties for services such as financial consulting, which results in the transfer of funds from the nursing home directly to the nursing home operator or their family by way of the related party owned by the individual in question. Currently, more than 70% of the nation’s long-term care facilities engage in this practice.

While utilizing related parties is not illegal, watchdog groups argue that nursing homes overpay their own companies in order to turn a personal profit. The facilities, in contrast, assert that spreading the operating costs to these other businesses controls costs and limits financial liability. Michael Wasserman, the former CEO of the company that provided administrative assistance to almost all of Brius’ facilities, told the Washington Post that Rechnitz’s approach to making financial decisions for his nursing homes “would be made looking at the bottom line rather than what was the right thing to do for the residents.”

In total, Brius-operated nursing homes pay approximately 40% more per bed than other nursing homes in the state; advocates against Rechnitz’s behavior allege that this increase in funds arises from a desire to route the money through related parties and back to Rechnitz and his family. Five companies related to Brius shared their tax returns; one was a related party offering financial counseling, and the other four were holding companies that produced no good or services.

According to an investigation by The Post, the financial counseling party—Boardwalk West Financial Services—is 99% owned by Rechnitz, with his wife Tamar claiming the other 1%. Boardwalk received $2.6 million dollars, of which nearly 1.3 million was paid to Rechnitz and Tamar as a cash distribution. The four holding companies acquired almost $40 million, paying out distributions of $28 million to Rechnitz and his wife.

The State of Brius Nursing Homes

Brius facilities have come under fire across California for their lackluster inspection scores, with staffing being one of the primary concerns. Allegedly, the staffing coordinator for one nursing home was not aware that the state offered mandated paid leave during 2020’s coronavirus pandemic, instead requiring employees to exhaust all of their unpaid sick and vacation time. Brius facilities have been home to a number of residents who sustained severe injuries or even died as a result of insufficient oversight by staff; at one location, a 57-year-old resident was able to exit the building unnoticed and douse herself with gasoline before igniting herself in an alley. She passed away hours later, and Brius offered no comment on the case, citing patient privacy.

This is just one of Brius’ many nursing home neglect and abuse lawsuits in recent years. As the investigation into Brius Healthcare’s financial operations continue, further light may be cast on a growing number of negligence cases in the facilities.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Reply TO PLAINTIFF’S OPPOSITION TO PETITION TO COMPEL CONTRA

To compel contractual arbitration and motion for stay Bruis, LLC; Shlomo Rechnitz, an by difendants Brius, LLC; SAN individual; Nora DE Leon Flores, an Mateo Wellness GP, LLC dba individual; Shirley Faller, an Burlingame skilled nursing; individual; Susan Ehrlich,

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rechnitz opens his home to the needy - not only to distribute money, but also to hear their stories and to offer the most effective solutions to the problems that might be plaguing them. When Hurricane Sandy struck

0 notes

Text

What Does the Shlomo Rechnitz Controversy Have to do with Nursing Home Abuse?

In the last three years or so, California news reports have followed the story of the many legal disputes involving nursing homes owned by Shlomo Rechnitz. In some respects, the controversy is simply a matter of business disputes, but part of it actually has to do with allegations of nursing home abuse. In 1998, Rechnitz and his twin brother Steve founded a medical supplies company called TwinMed, and their business interests grew from there, to the point that, by 2016, about 7% of California nursing home residents lived in facilities owned by Rechnitz. The Sacramento Bee ran a series of articles detailing the violations and complaints associated with nursing homes Rechnitz owned or operated.

Doctors and nurses have a duty to provide care for patients in nursing homes, and failure to meet that standard of care constitutes medical malpractice. Title 22 specifies what the standard of care is that nursing home employees owe to patients. Here are some examples of complaints originating in nursing homes associated with the Rechnitz controversy and how they represent violations of the standard of care.

Nursing Home Fails to Meet Patient’s Dietary Needs

According to Title 22, nursing homes must give patients as much feeding support as they require, but not more. Feeding tubes should only be used if there is no other way for the patient to receive nutrition. At Alameda Healthcare and Wellness Center, a patient lost 11% of her body weight in four months because of inadequate feeding support. She had some difficulty swallowing on her own, but would have been able to eat if the food had been less dry. The patient requested more gravy be added to her foods, but the dietary aide did not notify the nursing home cook of this preference until the patient had lost a lot of weight.

Improper Infection Control Procedures

Title 22 specifies that nursing homes must follow medically recommended practices to prevent the spread of infections and infectious diseases within nursing homes. At Oakhurst Healthcare & Wellness Center, insufficient measures to control infection led to seven patients and one staff member becoming seriously ill. Investigators found that the nursing home staff were not following proper infection control protocol in terms of hand washing, cleaning of surfaces, and washing of linens. In another Rechnitz-owned facility that has since closed, a patient died from sepsis after the staff of the nursing home failed to follow the correct infection control procedures. In this case, the patient contracted a fatal infection after her wound dressings became contaminated. An investigation of the nursing home showed that, in general, the staff was not doing enough to prevent the spread of infection; this was obvious from the cleanliness of the kitchen and bathrooms and from the garbage removal procedures.

Contact Case Barnett About Nursing Home Abuse

California laws are clear about the standard of care owed by nursing homes to their residents. Contact Case Barnett in Costa Mesa, California if you think that the nursing home where your family member is being treated is in violation of the legal standards for nursing homes.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Shira Choir Sings New Song At Bar Mitzvah - מקהלת שירה מבצעת את השיר החדש ׳אם השם לא יבנה בית

Chorale juive Orthodoxe

Ce morceau A cappella « Im Hashem Lo Yivneh Bayis » a été composé par Shlomo Yehuda Rechnitz pour la Bar Mitzvah d’un des fils du fondateur de la chorale Shira, Shraga Gold à Williamsburg.

A écouter, votre néchama (âme) va briller !

Site internet : https://shira24.com/

1 note

·

View note