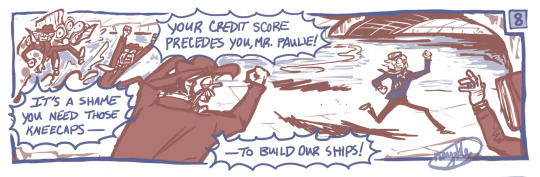

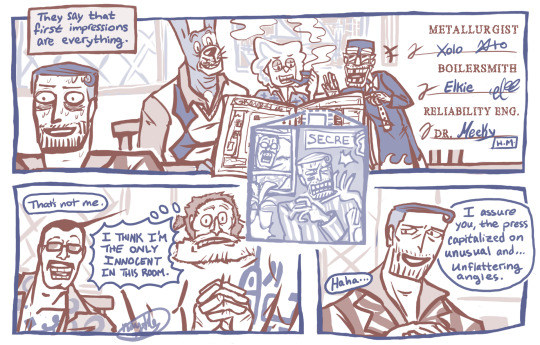

#Tilestone can do no wrong

Photo

Crazytrain - 8

#One Piece#One Piece fanfiction#OP fancomic#Iceburg#Paulie#Peepley Lulu#Tilestone#OPC Xolo#OPC Elkie#OPC Meeky#One Piece OC#during timeskip#Galley-La#OP Crazytrain#naytile art#the specialist engineers arrive - all are real occupations#we've got a mink a human and a... a human#none are spring chickens!#Tilestone can do no wrong#I like that Paulie tries to be professional but still ends up sounding rude#dog-tleman?#Tyrannosaurus is hiding#Lulu lies while Burg tries to save PR - two kinds of people#i lol bc the foremen were expecting these BIG. BURLY. MEN. aka: people exactly like them

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The plasticity of the notion of reading meant that it represented the medium through which middle-class Victorian girls passed many hours, but it did not bring a uniform message. Like their parents and advisers, adolescent girls who were writing about reading were of two minds. On the one hand, as William Thayer put it, reading could be a way of demonstrating rectitude and diligence; on the other, it could be a route to indolence and the shirking of responsibilities.

Mary Thomas, away at school in Georgia in 1873, suggested these dual meanings of reading as she imagined a newly virtuous domesticity for herself upon returning home: ‘‘I will sew and read all the time, I am not going out any where, but intend to stay at home and work all the time; no matter how interesting a book may be, I will put it down and do whatever I am asked to do, they shall no longer accuse me of being lazy and good for nothing, I will work all day.’’ In its contrast to engaging in a social whirl of visiting and flirtation, reading, like sewing, represented a becoming and modest domesticity. However, reading might also subvert good intentions, and tempt a girl to inattention to, or even disobedience of, the demands of others or of household work. In any case, reading had a meaning for the self, as well as for the family and the culture.

Reading good books was of course a way of demonstrating virtue. Measured reading of improving texts was part of the regimen of many Victorian girls. As advisers suggested, the reading of history was especially praiseworthy. When Nellie Browne returned home from school in 1859, her mother noted in her diary with pride, ‘‘Nellie begins to read daily Eliot’s History of the United States,’’ a parentally encouraged discipline which would both improve and occupy Nellie now that her school days were over.

Jessie Wendover, the daughter of a prosperous Newark grocer and another regular diarist, recorded a steady diet of history in her journal, justifying her summer vacation in 1888 with the reading of a two-volume History of the Queens of England, as well as doing a little Latin and some arithmetic. The popular British domestic novelist Charlotte Yonge wrote her History of Germany specifically for readers like Jessie Wendover, who began it the following year. What American girl readers took from the history they read is hard to ascertain, because unlike their rapt reports on novels, they recorded their history as achievement rather than illumination.

One can certainly appreciate the irony, though, in encouraging girls to read accounts of national travails, the stories of armies, wars, and dynastic succession, which were ennobled partly by their distance from girls’ real lives. One of the advantages of history seemed to be that girls could be expected to have no worrisome practical interest in it—in marked contrast to the reading of romances or novels.

Victorian girls could build character through a variety of other literary projects, prime among them the memorizing of poetry. Over the course of the late nineteenth century, the publishing industry issued a number of collections of snippets of poetry known as ‘‘memory gems,’’ designed for memorization by schoolchildren. The verse in these anthologies was to serve as ‘‘seed-thoughts’’ for earnest young Victorians aspiring to know the best, and these were the likely sources for many of the couplets which appear in girls’ diaries and scrapbooks.

Margaret Tileston’s daily diary, recorded religiously for her entire life, both fed and celebrated a variety of literary disciplines, including most prominently reading and memorizing poetry. She too read histories during the summer, along with keeping up with her other studies, noting one July day following her graduation from Salem High School that she had ‘‘read my usual portions of Macaulay [a 40-page allotment] and French, but only a few pages of Spencer.’’ Margaret Tileston also read advice literature, such as Mary Livermore’s What Shall We Do with Our Daughters? and two books by Samuel Smiles, Self-Help and Duty. (The latter she described as looking ‘‘quite interesting and full of anecdotes.’’) Margaret Tileston’s diaries suggest a life consumed with the rewards of self-culture.

At fifteen, however, she recorded a brush with another literary genre and mode of striving—a seeking not only for mastery of the will but for beauty itself. Poetry first appeared simply as a verse of romantic poetry copied on the page: ‘‘Why thus longing thus forever sighing, for the far-off, unattained, and dim, while the beautiful, all round thee lying, offers up its low, perpetual hymn.’’ Margaret Tileston was now away at girls’ school, where she had experienced something of an emotional awakening in the intense atmosphere of schoolgirl friendships.

Her turn to poetry seems to reflect the new culture in which she was briefly submerged. That summer, back with her family on vacation on the Massachusetts coast, Tileston again turned to poetry, and to beauty, in an uncharacteristic passage of effusion. ‘‘The moon was perfectly lovely in the sky and its light on the water. We quoted lines of poetry, and it was beautiful.’’ By January of the next year, however, poetry had been incorporated into her disciplines of order and accomplishment. After returning from boarding school, she had moved with her family from the farm where she had spent her formative years to the town of Salem, where she attended the local high school. There she embarked on another campaign of self-improvement, the memorization of poetry, perhaps as a strategy to gain control of alien surroundings.

Two months later she described a new discipline: the daily ritual repetition of all the poems she had learned, of which there were by then 111. On May 25 she reported that her extraordinary ability to memorize poetry was gaining her a reputation. ‘‘Miss Perry asked me if I knew about 250 poems. She said that one of the Goodhue girls had told her I did. I remarked something of the sort to Miss Perkins one day in recess, and somehow it was repeated.’’ By the end of July she noted that she was beginning to have trouble finding new poems to learn because she knew so many already.

Appreciation of the beauty of poetry had dropped out of her journal. Nor did she suggest that the poetry had any meaning to her at all. Yet she very likely gained some of the satisfactions from poetry expressed by Louisa May Alcott, some years before. After disobeying her mother, at the age of eleven, Alcott ‘‘cried, and then I felt better, and said that piece from Mrs. Sigourney, ‘I must not tease my mother.’’’ She went on, ‘‘I get to sleep saying poetry,—I know a great deal.’’ For those feeling guilty, sad, misunderstood, or wronged, repeat- ing lines of elevating poetry had an effect in a secular mode analagous to the saying of ritual Hail Marys. The verses established an alliance with a higher authority and suggested personal participation in a glorious and tragic human struggle.

And in fact, poetry, even more than history, was the prototypical idealist genre. In 1851 the British educational pioneers Maria Grey and Emily Shirreff proposed the reading of poetry rather than fiction, explaining the crucial distancing effect of poetic subjects. ‘‘In a poem, the wildest language of passion, though it may appeal to the feelings, is generally called forth in circumstances remote from the experience of the reader.’’ They suggested that in poetry there was a higher truth than that of superficial realism: ‘‘The grand conceptions of the poet are true in ideal beauty.’’

Writing fifty years later, Harriet Paine too suggested that poetry had generic qualities of elevation. ‘‘After all, in poetry itself what we read is not the important thing. We should read poetry to give us a certain attitude of mind, a habit of thinking of noble things, of keeping our spirit in harmony with beauty and goodness and strength and love.’’ Earlier Paine had commended the memorization of poetry as neces- sary to ‘‘take in the full meaning,’’ suggesting just such a regular regimen of repetition as Tileston had pursued. The spiritual rewards from internalizing poetry were revealed by Paine’s proposal that it take place on the Sabbath: ‘‘Surely we must give a part of every Sunday to such elevating study.’’

Elizabeth Barrett Browning had censured poets for their historical escapism in her 1857 poem Aurora Leigh, arguing Their sole work is to represent the age, Their age, not Charlemagne’s—this live, throbbing age, That brawls, cheats, maddens, calculates, aspires. Yet it was in just its remoteness from ‘‘this live, throbbing age,’’ just in the ‘‘togas and the picturesque’’ disparaged by Browning that poetry was considered so appropriate for girl readers.

…If reading presented an opportunity to discover national allies, to demonstrate private virtue, and to suggest the triumph of the will against ennui or boredom, it increasingly endorsed another way of defining life: the excitement and the exercise of the feelings. Girls who read their daily allowance of Macaulay or the Bible with pride and self-satisfaction upbraided themselves for their difficulties in controlling their insatiable appetites for Victorian novels of all kinds. Reading for leisure or for pleasure invariably meant reading for ‘‘sensation,’’ reading for adventure, excitement, identification, titillation. In the process of this kind of reading, Victorian girls ministered to a complex of emotions.

…Perhaps leisure reading can best be defined by what it was not: study, sleep, or sewing. Girls chastised themselves for imperfectly learning their lessons, and sometimes blamed the distractions of leisure reading. Martha Moore, who had just begun to attend school in occupied New Orleans during the Civil War, confessed that she found the schoolwork hard and had had two crying spells before she ‘‘picked up an interesting story and with my old habit of procrastination, thought I would read that first, and then study.’’

She observed the inevitable consequence ‘‘that my lessons are very imperfectly known.’’ And even Margaret Tileston, whose discipline seldom allowed her to swerve from duty, could be seduced by light reading. At the age of fourteen: ‘‘I scarcely studied in my history at all, because I was interested in ‘Sir Gibbie,’ and wanted to finish reading it.’’ At the age of seventeen: ‘‘I undertook to spend the afternoon and evening on my Ancient History, but my thoughts wandered and I spent some time on papers and magazines.’’ At the age of twenty: ‘‘I did not study a great deal in evening, on account of my interest in my novel, but I read over my History lesson.’’

Girls also resolved to prevent reading from interfering with their domestic chores, usually their needlework. Treating reading as recreation, Virginian Agnes Lee observed, ‘‘I really am so idle I must be more industrious but it is so hard when one is reading or playing to stop to practice or sew.’’ Another Virginian, Lucy Breckinridge, set up a similar opposition, noting that she and her sisters had gathered together in her room ‘‘being industrious. I am getting over my unsocial habit of sitting in my room reading all day.’’ For Lucy Breckinridge private reading not only was not industrious, it was also antisocial.”

- Jane H. Hunter, “Reading as the Development of Taste.” in How Young Ladies Became Girls: The Victorian Origins of American Girlhood

2 notes

·

View notes