#and then I came up with an internal research proposal and methodology and am in the process of implementing it

Text

I have achieved peak evolution from ‘the weird kid who remains quiet during social events unless it’s to give a deeply disconcerting insight’ to ‘that one researcher who actively has research plans and frameworks on human psychology and behaviour who is a really good source if you need insight on a social situation’.

#my friend: oh by the way I have new data for you and a new research subject you might find interesting#me: heart eyes instantly ‘oh?’#and then I came up with an internal research proposal and methodology and am in the process of implementing it#my work on queerness and the social construction of gender and attraction is surprisingly valuable!#the best ppl I know just come like ‘I know you’re running some sort of experiment and you’ll tell me the results at some point’ when I ask#Then recently I was like ‘btw I have new information on a certain social situation’ and my friend was immediately like ‘meet me for lunch?’#I wld probably be better at studying if I was worse at this but#It’s a very useful social behaviour to have and I rather like it so I’ll just compensate#Brought to you by a neurodivergent queer studying queerness in literature#Oh actually I disagree with my old frameworks when I reread my paper#could have done more with the concept of the counterpublic and based it more deeply in queer theory#because I misused a few concepts but yeah#Syl’s ramblings

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Radical Rituals

forty-five degrees is an open collective of architects and designers dedicated to the research and critical making of collective space. They take different forms when engaging in collaborations with other experts, adapting to the project’s scope. In their practice, space-making is about resources, not only material or financial but the intangible resources of human and non-human knowledge.

Talking in the park in front of Tageszeitung in Berlin-Mitte with Alkistis Thomidou and Berta Gutierrez. | Photo © Boštjan Bugarič

Their work aims at investigating the built environment through research, design and artistic experimentation, across multiple scales and in its social, economical and structural entanglements.They are collecting protocols and collective approaches, exploring alternative living and city making models and new paradigms of urban development to engage with communities and local agents. They strive to create inclusive and accessible spaces through careful use of scale, material and design language with a commitment to rethinking education through academia and practice placing design at the intersection of arts and sciences. Berta Gutierrez and Alkistis Thomidou were talking to Boštjan Bugarič.

***

For this interview we meet in a new park next to Hejduk’s Tower; why did we meet here?

BG: I really appreciate Hejduk's theoretical work and I find it very relevant nowadays since I believe it can give us many leads on how architecture should be taught during the contemporary crisis.

In 2010 the architecture community gathered to protect the Kreuzberg Tower as new owners began altering the facade. | Photo © Boštjan Bugarič

Around this park are also other important buildings?

AT: On the other side we find a first cooperatively built project for offices, FRIZZ, and on the other there is also the new TAZ building.

This park is divided with paths (lines), how can we create these lines?

AT: This area had a very strange atmosphere although it is quite central. I am actually the first time in the park after its renovation. These lines cutting through the space shall be a result of shortcuts where people cross the former park, literally, the footprint.

“Radical Rituals” is an itinerary survey along the 45ºN parallel, on the inventiveness of everyday life, new hybrid vernacular practices and rituals that stimulate and nurture the commons across Europe. | Photo © forty-five degrees

What about your line, the forty-five degree? What is a project about?

AT: The name came along with the idea of a research of the 45ºN parallel as many people in our team come from the south of Europe but studied or work and live in the north part of Europe. This line has influenced our way of thinking and although it is a fictional line it burdens Europe and represents a border that people try to cross every day from South to North. We wanted to investigate what is happening along this line that crosses France, Italy, Croatia, Serbia, Romania all the way to the Black Sea. Although it cuts the middle of Europe, cities around it are considered ‘peripheral’. We are researching how the European identity is reflected along this line.

Polarisation between north and south, heterogeneous economic models, diversity of cultural and historic backgrounds. | Photo EW Elsevier Weekblad, Issue 22, 2020

What have you discovered so far?

BG: We are currently preparing our first field trip, and we will be in Romania and Serbia by September. Right now this is a very fascinating part of the project as it is like a zoom into the ground. If you go very far away, you see the meridians and parallels as the way of shaping the world, but when you start to get closer, you see countries, borders, cities, landscapes and people. We would like to zoom in as much as possible, so we can really understand local situated practices that are happening in very specific physical environments.

AT: The project “Radical Rituals” is a survey on very local spatial practices or initiatives that addresses climate challenges, space justice and biodiversity. We want to be surprised by what we learn along the way, what kind of collectivity is created and how local identities can influence space production.

A British writer Shumon Basar references the metallic flowers of Hejduk on the facade as,"grips for angels to hold onto when they climb the sides of the tower” inspired by “Wings of Desire"by Wim Wenders. | Photo © Boštjan Bugarič

BG: In this sense it is great that we are in front of Hejduk’s building because he proposes the way in which design comes as a result of small narratives or characters entangled with each other, working with crafts or local materials and contexts. For us the exercise is similar, but instead of working with fiction we work with reality as nowadays reality is complex enough. We don’t have all the answers to these challenging topics, but we believe that this exercise will give us a sort of light.

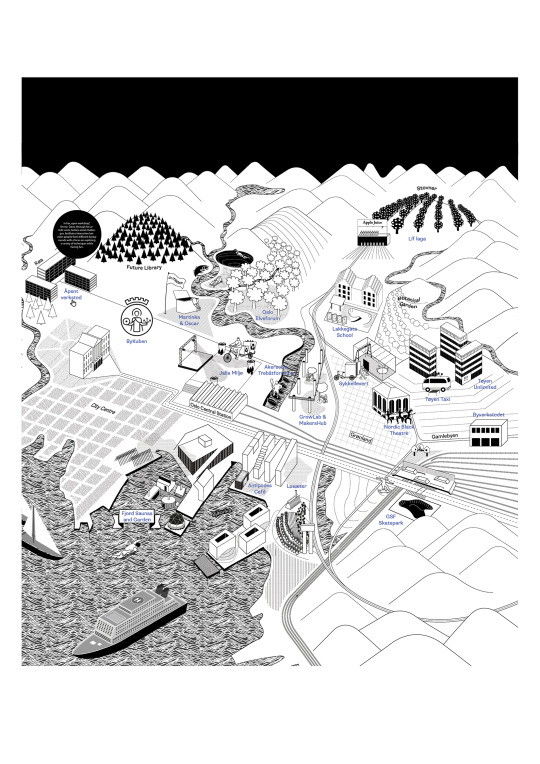

AT: Through this research we want to see what stories point to possible futures and possible present-s as people develop tools and knowledge that is embedded in the context of the local space. We worked on this concept at the Architecture Triennial in Oslo, where we created a digital Atlas that connects OAT’s archive and discourse with the transformations that take place on the city’s ground through local initiatives. We encountered initiatives that manage to achieve systemic changes and give multiple answers to the big challenges we are facing. In a way, proving that the environment is a primal source of our knowledge.

Oslo In Action(s) is a research project uncovering city-makers who stimulate and nurture the commons beyond the boundaries of professional practice.

The Digital Atlas was commissioned by the Oslo Architecture Triennial for their 20th jubilee “Conversations about the city". | Photo © forty-five degrees

Your practice was as well put on the list of the Future Architecture Platform? How do you see yourself in the FAP?

AT: It was an important experience to have this opportunity of working with people and institutions. We met extremely generous and inspiring people in Ljubljana and then in Oslo. Then, we got the digital research fellowship at Architectuul which enables us to meet and connect with other projects and not just sit in our office and work on the research but expand our network and bring different perspectives together. We are very grateful that the Future Architecture Platform gave space for this project.

Initiatives in Oslo (up) and Urtegata Sykkellevert space for multimedia production and Tøyen Taxi. | Photo © forty-five degrees

Just finished curating a panel on Kvadrato, how did you choose panels and why you wanted to present them?

AT: The panel was called ‘Communication for Commonalities’, where we invited diverse initiatives that work collectively and with several communities. Their work spans from creating digital platforms that communicate collective intelligence on a global scale, to very local projects that engage directly with a variety of actors on the ground.

With Akerselva Trebåtforening, we paddled on a 100-year-old wooden boat on an underground river running into the fjord (up); Losæter is the city farm of Oslo. | Photo © forty-five degrees

BG: It was a great example for us to address our questions and concerns and discuss them in the context of communication of architecture. As we know, communication in architecture is about media and its symbolic representation. Nevertheless, for us communication is related with the ground, physical context, methodologies and the communication channels that people use to promulgate the project with peers or bigger networks.

The Fjord floating saunas - Oslo Badstuforening. | Photo © forty-five degrees

The legendary GSF Skatepark. | Photo © forty-five degrees

The Oslo fjordhage, a floating classroom dome. | Photo © forty-five degrees

How you integrate the theoretical methods in the learning process?

BG: In my personal research I try to answer the question of how do we promote other ways of learning coming from non-disciplinary practices since academia became such a rigid space with a very outdated curriculum. With non-disciplinary practices beyond academia we can really find many inputs on this crossing.

Berta Gutierrez and Alkistis Thomidou | Photo © Boštjan Bugarič

AT: We are currently collaborating with two other international practices on an Erasmus+ Youth in Action project on how to learn together. During the next two years we will develop formats of different ways of learning and engaging youth to physical interaction with various spaces in the city, public, private or common areas. We see the engagement of young adults in space-making processes as a project of emancipation and investment in the future.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dissertation Prospectus: The Development of South Korean Prisons and Penology, 1945-1961

Dissertation Prospectus

[Please DM for file with full citations]

“The Development of South Korean Prisons and Penology, 1945-1961”

I. Project Overview

Stripped of its legitimating discourses, imprisonment is the simple act of putting human beings into cages. By the mid-twentieth century, the practice of incarceration had spread by means of Western colonial expansion to nearly every area of the globe. Many of the formal vestiges of empire fell away after the second World War, but Western-style incarceration remained a worldwide practice. The project to modernize the Korean prison system continued long after its initial development during the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945). After a chaotic period under the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK; hereafter “MG”) (1945-1948), South Korean penal officials were immediately swept up in bold prison reform efforts. My dissertation research examines the ways South Korean penal reformers imagined the past, present and future of the prison system during Korea’s tumultuous 1950s. I am working to map the cultural, political and economic influences on Korean penology and its discourses in the early Cold War era. The United States government relied on the internal stability of South Korea as an East Asian bulwark against communism, and directly shaped the development of the penal system within the Cold War system. This study has larger implications for the general history of 1950s South Korea, Cold War international relations, and the development of power and social control in the Republic of Korea (ROK) state by historicizing a crucial institution used for state control of the incarcerated and free population alike. This dissertation will argue for rereading the history of the South Korean prison as a crucial site for the production of notions of ROK national identity and citizenship.

The historical timeline of this project extends from Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule and subsequent division by the U.S. and Soviet Union in 1945, through the Korean War (1950-1953) and fall of the Syngman Rhee regime in 1960, and ends with the coup d’etat by General Park Chung Hee in 1961. After the establishment of the Republic of Korea in 1948, penal reformers proclaimed the goal of “democratizing” the prison system under the slogan ‘Democratic Penology’ (minju haenghyŏng). Prior to the Korean War, prisons were underfunded, overcrowded, and used for ostentatious performances of anticommunist conversion. However, by the late 1950s penal officials boasted of the prisons’ humane conditions and state-of-the-art rehabilitative and educational function. Exhibitions displaying prisoners’ paintings, calligraphy, craftworks and writings evidenced their “reformation” for the public. How did the state of prisons change so drastically over a single decade, and how much of these claims is simple propaganda? These purportedly liberal reforms were carried out by the notorious authoritarian regime of South Korea’s first president, Syngman Rhee. Penal practice departed drastically from reformist theory when it came to punishing political opponents of the regime, but the prison system nevertheless did see major changes in the overall treatment of prisoners and training of penal officers. At the same time, this official narrative of reform is conspicuously silent with regard to the state of prisons during the Korean War (1950-1953), a period in which tens of thousands of political prisoners were massacred.

The devastation of the conflict left nearly every South Korean penal facility in ruins. Postwar reconstruction efforts focused not only on the rebuilding of existing prisons, but also the addition of new, state of the art facilities. With the help of material aid from the United Nations and the United States, Korean penal reformers began to transform their system in the image of their Cold War allies. Post-Korean War penal practice took on the guiding ideologies of liberal democracy and ‘penal education’ (kyoyuk hyŏng). The new system emphasized job training and rehabilitation of prisoners for reentering society. Penal reformers also embarked on UN-sponsored trips abroad to study the prison systems of the U.S. and Western European countries. These officials debated responses to the challenges facing their system in the pages of professional journals and books on penology and its history. While the period spanning South Korea’s first republic (1948-1960) stands as a crucial first stage of autonomous penal reform, it remains understudied in the field of Korean history.

Through my analysis of the discourse in professional journals of penal administrators, prisoner educational materials, and the memoirs of former guards and inmates, I will ask the following questions: What rules governed what could be said about the socially deviant and their treatment? What behavior constituted true violation of the social contract and what acts would be punishable by death? How and why was the idea of rehabilitation of convicts sold to the public? How were these rules affected by the Cold War system? What statements were qualified and by whom? When penal reform efforts were obviously failing, what political goals were achieved by state officials and civil society members claiming the contrary? Why was it culturally and socially significant to portray images of the well-ordered prison to the populous? I will trace the changes in these discourses of criminality and reform in the early ROK to explicate the pivotal role of punishing the deviant in the reflexive formation of national identity and solidification of state power.

II. Theoretical Framework: The Prison, the State, and Power

This dissertation, as it deals with the repressive apparatus of the prison, also deals concomitantly with theories of state power and violence. It interrogates the thesis of colonial continuity in the post-liberation state. The Korean history field assumes direct continuity between the colonial and post-liberation states without agreeing on a clear methodology or framework for locating which actors and institutions qualify as the “state.” Max Weber, one of the many scholars expounding on just what constitutes the state, defined it as the “human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force.” The parenthetical status of “success” in this translation perfectly reflects the tension at the heart of this project. The prison system was a vital tool for solidifying state power that acutely manifested the evolving relationship between subject and sovereign, but its supporters constantly struggled to defend its legitimacy and exaggerated the effectiveness of reforming inmates in the crisis-ridden institution. The U.S. occupation and Syngman Rhee regime inherited the colonial prison system’s veneer of legitimacy in incarceration as a practice resulting from due process of law, but continually reverted to extrajudicial and exceptional violence to solidify control of their territory. Giorgio Agamben’s work reveals this sovereign exception, the violent act of exclusion of the killable other from qualified political life, to be as old as the polis itself. Agamben amends Michel Foucault’s notion of state racism—the normalizing precondition that allows for killing internal others —to include all states, not just their modern and totalitarian instantiations. However, analyzing cases under the the Cold War system presents novel challenges to these theories of state power and violence: ROK authorities’ indiscriminate massacre of ideological prisoners without regard for loss of legitimacy reveals that their monopoly of violence was legitimated by the external machinations of Cold War containment, rather than an internally derived pact between the state and citizenry. This dissertation examines the shifting status of ROK sovereignty and authority to punish and kill through periods of both occupation and an “autonomous” South Korean government.

The U.S. occupation had to ‘rebuild’ the state in the momentary absence of the Japanese colonial repressive apparatus: this dissertation views prison-building as a part of state-building. Bruce Cumings has shown how Korea’s transition period from colonial to occupation state power was a crucible for popular resistance to underlying social contradictions that often pitted the rural populace against representatives of central power in the capital. Penal systems have a distinct function for suppressing such revolt by controlling bodies and flow of information in prescribed spaces, part of a process that Anthony Giddens calls “internal pacification.” Internal pacification is a generalized phenomenon that establishes “locales” to “promot[e] the discipline of potentially recalcitrant groups at major points of tension, especially in the sphere of production.” Neither the U.S. military occupation nor the fledgling Rhee government could claim total control of the peninsula’s mountainous regions, but improving surveillance networks through an archipelago of carceral institutions made both rebel activity and common criminality ‘legible’ as sets of tables, statistics and programs for social engineering. This project will treat provincial jails and prisons as outposts of pacification, simplification, and the spread of central power to the whole of the Korean peninsula.

Researching postcolonial societies in their immediate post-liberation period also reveals the nebulous nature of the state as a set of institutions, discursive effects, and material realities. Timothy Mitchell has proposed analyzing the state “not as an actual structure, but as the powerful, metaphysical effect of practices that make such structures appear to exist.” At various points in the analysis of early ROK penal history, the prison system appears as more idealistic rhetoric than fact, but it nonetheless projected the effects of a (re)developing state apparatus. Examining Korea’s ‘Liberation Space’—the period after 1945 when political control of the Korean peninsula was still in flux—and tenuous sovereignty after 1948 is better served by Foucauldian power analysis and his idea of ‘governmentality’: the “institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, the calculations and tactics that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power, which has as its target population, as its principal form of knowledge political economy, and as its essential technical means apparatuses of security.”

This approach allows for analyzing discourse as both an instrument and effect of power, identifying the “decentered and productive nature of power processes.” Traditional political histories fail to locate, or misattribute state power as a possession of a select few actors in the Syngman Rhee regime without accounting for the persistent local contestations to central power or the ambiguous status of South Korea’s sovereignty in the U.S.-dominated Cold War system. This dissertation asks how power was produced and maintained in early South Korea by diverse sets of actors and discursive effects of state and non-state institutions alike. Foucault’s reframing of modern power as a matrix of relations dispersed throughout the social body allows for thinking social existence beyond the juridical and state horizon: Power is not held, but constantly negotiated. Previous scholarship has looked for the emergence of such Foucauldian phenomena as governmentality, biopower, and panopticism before and after colonial annexation, but there has been little scholarship about what became of these dispersed power relations in the interlude between the colonial and U.S. occupation, how they were reified in the military government, or how they manifested in the ROK state. Korea’s ‘Liberation Space’ has been characterized as a power vacuum, but one can reexamine the period through the prison as a representative institution that facilitated the continued spread of disciplinary power in post-liberation society. Analyzing governmentality in this period problematizes Foucauldian models’ linear progression toward the telos of the Western European nation-state. Was the spread of these technologies of colonial state power truly continuous? Or was their spread halted and then redeveloped? Is modern power a one-way threshold or cyclical phenomenon capable of starts and stops, progression and regression? The broader goal of this research is to examine the rebirth and/or afterlives of governmentality and modern power in post-liberation Korea.

III. Methodology

This dissertation will utilize discourse analysis to track changes in notions of criminality, deviance, and its punishment in post-liberation Korea. The existing penal historical scholarship on the early South Korean prison system, which is minimal, has merely identified the gaps between penal officials’ theory and their practice, limiting analysis to the immediate space and functions of the prison and simply concluding that little had changed between the colonial and ROK penal systems. This narrow approach confines historical analysis to prison spaces without accounting for the myriad social forces that shape penal policy and their (in)efficacies.

A more thorough Foucauldian discourse analysis will allow for reading between the lines of official discourse to identify subtle changes in framing and rhetoric that signify larger currents in not just the prison system, but in the broader society as well. Shifts in penal discourse reflect changes in modes of production, emergence of new mentalities, and changes in power relations between the citizen and state. This dissertation will ask why significant thematic shifts in penal discourse occurred when they did, identifying the larger social and historical forces that shaped popular assumptions about citizenship and its deviant other. This analysis will answer these questions to account for the porous nature of prisons as spaces productive of a power that comes to permeate all social relations in the modern state. It will identify the dialectical nature of the prison that both affects and is affected by social and historical change.

More specifically, this dissertation will primarily focus on the post-Korean War discourse of “democratic penology” (minju haenghyŏng), a guiding principle of late-1950s penological texts that elevated the rehabilitation of the prisoner to the status of (re)building the nation itself. A more integrated analysis of both official and public discourse on punishment reveals the ways the Cold War system came to colonize the very consciousness and subjectivity of ROK citizens, shaping the way individuals viewed basic categories of the criminal and what constituted the ideal democratic citizen. One of the basic arguments of this dissertation is that early South Korean penal culture was fundamentally shaped by transnational interaction with the penological regimes of the U.S. and United Nations during the Korean War. The Cold War system influenced penology by reframing rehabilitation as the necessary work of reforming unruly bodies susceptible to idleness and communism into industrious, educated participants in the crusade to build a “Free World.” In this way, the Syngman Rhee’s anticommunist authoritarian state regime utilized prisons as both a productive and repressive technology for maintaining control of prisoners and the broader public. Images of ideal ROK citizenship found their other not only externally, with the positioning of South Korea as the anticommunist opposition to their northern counterparts; ROK identity was also formed through the isolation, confinement, and reform of the internal deviant other.

IV. Writing Korea into Global Penal Historiography

This dissertation is an attempt to write Korea into the broader field of penal history to better understand local instantiations of the global spread of incarceration. The current field of U.S. penal history was largely inspired by the historiographical turn of the 1970s that reframed punishment as a technology of social control. While their theoretical approaches differ, penal historians working in the 1970s and 1980s fundamentally refuted the traditional narrative of the prison as a self-evidentiary necessity or universal good. Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1975) has had the most lasting impact on penal historians for fundamentally reframing the role of prisons in the development of novel forms of power, governance, and modern subjectivity. Foucault revealed the prison as a key site for examining the production of docile, normalized bodies in modern states. Additionally, the prison produced discourse of the deviant recidivist and presented itself as the sole answer to this self-generated problem. Foucault viewed this normalizing ‘power/knowledge’ of the deviant as both a repressive and productive force. These Foucauldian concepts help to contextualize the historical developments of post-1945 South Korean penal culture, where authorities repeatedly committed to the “failing” prison system while simultaneously producing knowledge about the criminal and deviant. This dissertation will interrogate the persistence of the prison form and its normalizing discourses across ruptures of the liberation, division, and the Korean War.

The field of Western penal history has been significantly focused on explaining the persistence of the prison despite its continual failure to achieve its proponents’ goals. The group of scholars contributing to The Oxford History of the Prison (1995) demonstrate that modern incarceration has almost always been ineffective in attaining its changing and even conflicting goals. For the purpose of reform, it has historically been impossible to find meaningful correlation between the quality of imprisonment and deterrence of crime. Prison also does not satisfy the public need for retribution: at any given time, the majority of citizens of modern societies perceive punishment as overly lenient. Even when the prisoner is simply considered a source of cheap or free labor, there are varied conclusions regarding the efficacy of productive labor in penal history. The general consensus is that Western imprisonment seldom, if ever, achieved the intended goals of its implementation: it self-perpetuates despite its internal contradictions. Rebecca McLennan has shown how U.S. penal reformers at various points from the nineteenth to mid-twentieth century continually portrayed the prison in a state of “crisis” as it expanded and solidified its hold as the dominant form of punishment. Crises in the modern state, both manufactured and real are met with political attention, expenditure of resources, and bureaucracy that takes on an expansionist logic and life of its own. Further research in Korean penal history presents a crucial case study for the persistence of the carceral form in material conditions starkly different from its development in Western Europe and the United States. It must critically examine the highly propagandistic discourse of early ROK reformers with evidence of the material conditions of war and poverty that threatened the very existence of the carceral apparatus throughout the 1950s.

Some penal sociologists claim that Foucauldian explanations for carceral expansion are too instrumentalist. David Garland challenges the Foucauldian view of an agentless, rational power driving the expansion of the carceral state, and revitalizes the Durkheimian view of punishment as the public’s passionate retribution against social deviance. For these scholars, punishment is highly imbued with cultural meaning and public participation. Garland seeks to go beyond Foucault’s perspective on power, demonstrating the ways the prison “satisfies a popular (or a judicial) desire to inflict punishment upon law-breakers and to have them dismissed from normal social life, whatever the long-term costs or consequences.” Philip Smith further questions Foucault’s erasure of the role of irrational concerns and cultural values in punishment. He responds to the Foucauldians, “how does the ideal type of disciplinary power intersect with broader systems of meaning? How does the civil sphere participate in surveillance? Under what circumstances might spectacle still play a role in social control?” This research will hold these approaches in tension with Foucauldian analysis, a framework developed from the specific historical case of Western European nation-states. Examining the sudden reversal to punitive retribution against social and ideological deviance during the Korean War must account for Korean penal development’s post-colonial and Cold War historical specificities.

This dissertation is further informed by Western penal historical scholarship that emphasizes the porous nature of prisons as social and cultural entities. Some have amended the Foucauldian view of one-way discursive production of prisoner identity as it overlooks the ways deviant subgroups were defined and defined themselves. Others have revealed how penal regimes respond to external stimuli, and sometimes even serve as the primary impetus for political formations in free society. Accordingly, historicizing the development of South Korean prisons must account for their reciprocal relationship to political and economic dynamics in the broader society along with the development of an emerging ROK national identity. The prison must be examined in its Korean context, as well as the regional and global context of the Cold War.

Contemporary penal historians have charted the expansion of the Western prison form to the rest of globe outside of Europe and North America. Comparative penal histories further accentuate the importance of differing local conditions that shaped the African, Latin American, and Asian experiences of penal modernization. Contributors to the influential volume, Cultures of Confinement (2007) center the role of cultural practices and social dynamics to develop a more comprehensive approach that “highlight[s] the extent to which common knowledge is appropriated and transformed by very distinct local styles of expression dependent on the political, economic, social and cultural variables of particular institutions and social groups.” Frank Dikotter reminds us that the prison, like all institutions, “was never simply imposed or copied, but was reinvented and transformed by a host of local factors, its success being dependent on its flexibility.” Not every case of colonial prison expansion was “successful” for colonial aims: Peter Zinoman’s Colonial Bastille demonstrates how French colonial prison spaces facilitated intellectual exchange across dispersed geographic locations and helped foment a Vietnamese national identity amongst otherwise disparate linguistic and ethnic groups of Southeast Asia. Clare Anderson presented a case with the opposite effect in British colonial India, where the prison forced cohabitation of traditionally segregated social castes—an offense severe enough to foment popular uprising across the subcontinent. Despite vast differences with the case of Korea, these examples demonstrate how development of the western prison form was not always an unproblematic or effortless technique of social control: the spatial entity of the prison brought together diverse social forces, impacting existing local conditions and drawing dynamic responses to reorganization of the social order. The same attention to local dynamics must be applied to the crisis-ridden early ROK prison system that took more than a decade to clothe, feed, and properly contain its inmates.

The English-language penal historical field’s shift in focus to colonial prisons revealed challenges to Foucault’s emphasis of the advent of disciplinary power in modern incarceration. While previous scholarship on the global rise of imprisonment framed colonial institutions as “laboratories of modernity” that employed state of the art technologies for effective governance, Zinoman found that “[French] colonial prison officials introduced no such innovations and ignored many of the putatively modern methods of prison administration that had been developed in Europe and the United States during the nineteenth century.” Dikötter emphasized that colonial or peripheral iterations of the penitentiary deviate from the Foucauldian narrative of imprisonment’s shift away from corporal punishment: “a history of the prison shows not so much the ‘disciplinary power’ of the modern state but on the contrary the many limits of the government in controlling its own institutions: prisons were run by a customary order established by guards and prisoners on the ground rather than by a panopticon project on paper.” Florence Bernault cites the persistence of retributive and deterrent violence in African colonial regimes to refute the correlation between modern governance and the decline of “state-inflicted destruction.” Proponents of the Western penitentiary reframed free individuals as subjects, while the colonial prison primarily constructed colonial individuals as objects of power. Black and brown bodies bore the brunt of colonial, retributive violence well into the twentieth century despite changes in metropolitan nations. Historicizing the advent and persistence of the carceral form in Korea must allow for local specificity that challenges common Foucauldian narratives of the development of bloodless, disciplinary power. Widespread corporal punishment, torture, and destruction of the body was maintained in the penal practice of colonial and postcolonial Korea until as late as democratization in 1987.

The rise of the prison in Western European metropoles paralleled the extension of political rights of citizens in the rise of the modern liberal state, and thus held great promise for nascent anti-imperial and nationalist modernization movements. Following this model, East Asian powers enthusiastically adopted the prison as a tool of social control, producing a well-disciplined citizenry as a preemptive measure to resist colonization, or, in the case of Japan, forcing legal modernization on their neighbors as a strategy of colonial aggression. Prisons were quintessentially modern facilities that promised rehabilitation of human beings and the (re)invention of the nation itself. Frank Dikötter’s study shows how late-Qing and early republican reformers were quite successful in developing modern penal facilities and practices, so much so that Western imperial powers demanded a regression to corporal punishment to bolster the deterrent effects protecting their extraterritorial interests in China. This clearly demonstrates the Janus-faced nature of the Western penal form’s entrée into East Asia: modern disciplinary power was reserved for white bodies and the prison otherwise served imperialist, capitalist endeavors. Daniel Botsman further details the advent of East Asian penal modernization in Punishment and Power in the Making of Modern Japan. Botsman analyzes penal institutions in Japan before Western influence, their hasty reform in the Meiji era, and the use of legal reform discourse to justify imperial expansion into the rest of East Asia. Once the carceral form came to dominate Western imperialist discourse of legitimate exercise of state power, Japanese historians raced to locate its origins before Western imposition in the Tokugawa stockade. Japanese reformers quickly developed model prisons and flaunted them as both tools of colonial legitimation and repression in Korea and Taiwan. These works by Dikötter and Botsman are the most prominent English-language works writing East Asia into global penal history, but no such work yet exists for the Korean case. This dissertation will start to write Korea into global penal history, tracing the development of the carceral form on the Korean peninsula through its colonial introduction and extending analysis beyond liberation. Historicizing the postcolonial South Korean penal system will reveal the ways postcolonial penal regimes both reflected and challenged penological trends after World War II, when the world historical system that brought imprisonment to every corner of the globe entered a new phase of global struggle in the form of the Cold War.

V. Korean Penal Historiography

The following section will outline secondary scholarship in Korean penal history, highlighting the ways previous scholarship has been limited by the thesis of a dichotomy between premodern and modern forms of punishment, and between colonial oppression and Korean resistance. Korean penal historiography has primarily focused on the late-nineteenth century introduction of the carceral form and its uses during the Japanese Colonial Period (1910-1945) to suppress resistance to Japanese rule. Chosŏn penal culture was primarily retributive with legal institutions relying heavily on corporal punishment for deterrent effect, and torture to extract confessions. By prioritizing the mere deprivation of liberty over physical harm of the body, the 1890s codification of carceral punishment and conversion of flogging to units of time served represented a monumental shift towards rehabilitationist penal thought during the Taehan Empire (1897-1910) period. While the question of autonomy of the Korean state to carry out penal reforms without colonial manipulation is debated in existing scholarship, it is clear that the continued rationalization of the Korean criminal justice system in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries aided the subsequent colonial state’s penetration of everyday life on the peninsula.

Historicizing Korea’s first modern prisons cannot be separated from their use by the colonial regime to detain, torture, and execute members of resistance movements. Lee Jong-min has shown how colonial penal modernization had political dissent as a primary concern, and more general crime as an afterthought. The explicitly political nature of penal reform continued into the colonial period, and saw a racialized recommitment to bodily punishment and ideological conversion. Previous scholarship focuses almost entirely on colonial penal authorities’ persistent use of bodily torture to refute the notion of colonial prisons’ “modernity.” This view uncritically accepts both incarceration and modernity as positive developments in a linear progression of the humane treatment of the subject by state power. More problematically, it reifies the notion of a more “humane” form of incarceration that hypothetically would have developed had it not been for the colonial intervention.

Scholars inspired by the “colonial modernity” paradigm questioned nationalist historical narratives, and problematized notions of “distorted” modernity. They do not see flogging as a disqualifying factor for a novel type of state power under Japanese rule, and present a nuanced reading of the development of Foucauldian disciplinary power that retained corporal punishment due to local specificities of the Korean colonial context. Flogging Korean bodies in the presence of medical doctors was a sophisticated technology of social control used in lieu of the underdeveloped use of incarceration and monetary fines, punishments that colonial authorities feared had not yet been sufficiently internalized by the local populous as deterrents to crime. By the end of the colonial period, Korea’s premier penal institutions had factories, educational programs, and ideological conversion programs aimed at cultivating ideal imperial subjects. Korea’s penal modernization was indeed colored by the colonial experience, but this fact should not cloud analysis of the global spread of disciplinary power through both colonial regimes and their post-colonial successors.

The Korean history field still lacks a comprehensive work detailing Korea’s post-1945 penal history in either the Korean or English languages. The most thorough narrative can be found in the Republic of Korea Corrections Bureau’s official history. While useful as a starting point for scholarly research, the work presents a hagiographic account of the triumph of the ROK’s modern penal practice over traditional and colonial practices, and uncritically accepts the development of incarceration as desired progress. The most recent edition of this state-sponsored history retains the Cold War-influenced, anticommunist narratives of the division and Korean War, notably silencing the early ROK penal system’s use in ideological indoctrination, preventive custody of political prisoners, and massacres of political prisoners. Political concerns aside, this institutional history fails to place Korean penal history in its social and political context, taking the prison form for granted and extending its history backward from the present day.

More critical academic scholarship in penal history attempts to contextualize development of the ROK carceral system, but the field has largely overlooked the period between the peninsula’s Liberation in 1945 and the 1961 military coup by General Park Chung Hee. The seminal work of Bruce Cumings and contributors to the first volume of Haebang chŏnhusa ŭi insik (Korean History Before and After Liberation) clearly established the role of the U.S. military occupation government in appointing collaborators and veterans of the colonial system in the early ROK police and legal apparatuses. The specifics of post-liberation continuity in the penal system from the colonial period have yet to be properly fleshed out, but existing scholarship paints a picture of overcrowded, underfunded, escape-prone prisons in the wake of popular resistance to U.S. occupation policy. Prisons were most crowded following the crackdown of the Autumn Harvest Uprising of 1946, a series of widespread clashes between central authority and local supporters of the ‘people’s committees’ that had sprung up after liberation. Though his work focuses primarily on prisons during the later Park Chung Hee dictatorship, sociologist Ch’oe Chŏng-gi briefly examines the post-Liberation turnover of prisons to contextualize colonial continuities in the penology and ideological indoctrination of South Korea’s subsequent authoritarian regimes. He attempted to explicate the “real conditions” (silt’ae) of post-liberation penal spaces, revealing that most of the personnel retained their positions from the colonial system, and newly hired officials received minimal training that changed little from the colonial model. Pak Ch’an Sik’s work revealed the strain on the penal system when mainland prison facilities received an influx of detainees after the 1948 Cheju Uprising, a series of revolts on Cheju Island that were met with a protracted campaign by the MG and South Korean authorities to massacre leftists, their collaborators, and ordinary citizens caught in the fray. Further research utilizing U.S. military archival sources will facilitate a more detailed understanding of the MG’s role in penal modernization, its colonial legacies, and the Cold War’s impact on South Korea’s penal history.

There is even less scholarship dedicated to the penal system of the First Republic (1948-1960), but prison spaces served a crucial role in suppressing leftist activity from the founding of the ROK in 1948 to the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950. Historian Kang Sŏng-hyŏn has provided detailed historical accounts of the early Rhee regime’s expanded categorization of “thought criminals” (sasangpŏm) after the 1948 passing of the National Security Law, the act that allows for the exemption of constitutional rights to due process and habeas corpus in cases related to national security. As prisons overflowed, the state attempted reeducation and conversion of ideological offenders through the euphemistically named National Guidance League (Kungmin podo yŏnmaeng). Historians working in the early 2000s exposed the history of forced reeducation and eventual wartime massacre of suspected leftists who were members of the League, but the League’s relationship to the penal apparatus needs to be examined further to better historicize changes in penal thought and practice at the founding of the First Republic.

Historical analysis of prisons during the Korean War emphasizes their use as sites of liberation or massacre while the peninsula changed hands back and forth between the ROK and DPRK. After the retaking of Seoul in the Fall of 1950, the Rhee regime used penal spaces for detainment and expedited execution of those suspected of collaborating with the Korean People’s Army (KPA) of North Korea. The literature on prisoners of war reveals a geopolitical layer to consider when charting the Cold War influence on Korean penal practice. Further research of the UN’s extensive POW and ROK civilian internee reeducation programs will show changes in ROK penal practice across the wartime rupture and account for the Cold War imposition of the Geneva Convention and United Nations-imposed penal paradigm. Nearly all of South Korea’s prison facilities were destroyed or damaged in the war, and reconstruction was still only partially complete as late as 1960. Other than a brief mention in the ROK Correctional Service official history, there appears to be no published research detailing the post-war reconstruction of the ROK penal system or its transformation to the “correctional” model in 1961. This dissertation will use diverse and previously underutilized primary sources to explicate the pivotal role of the prison and its discourses undergirding the social upheaval of the early ROK’s history of war and reconstruction.

VI. Primary Sources

Inspired by a Foucauldian model of discourse analysis, this research seeks to historicize changes in ROK penal culture by analyzing both official reform discourse and responses to its implementation on the ground. Primary source materials related to prisons in the immediate post-liberation period are scarce, and researchers must utilize both U.S. and local sources to develop even the most rudimentary account of the turnover of penal authority from colonial to occupation forces. The files of the United States Military Government in Korea contain the occupation government’s penal section records. MG administrators kept haphazard, and often handwritten reports on prison conditions and fluctuations in inmate totals, which also contained evaluations on changes in penal practice relative to their Japanese predecessors. These materials are invaluable for ascertaining the most basic information about the penal system after the transfer of authority from the Japanese colonial government to the U.S. military occupation. They will also help track the evolving MG penal discourse that celebrated perceived advances in reform while facing intensified resistance to the occupation. This dissertation will also analyze Korean print media sources to chart local perceptions and responses to prison overcrowding, organized escape attempts, and deteriorating prison conditions. After events like the Autumn Harvest Uprising of 1946, depictions of penal spaces and activities appear in more diverse archival sources produced by different sections of the military government tasked with suppressing rebellion, investigating hygienic conditions and prisoner abuse, and responding to reports of massacres.

This dissertation also examines the early development of the field of ROK penology—the study of prisons and penal practice. The liberation period saw a limited number of publications by Korean penologists establishing the state of their field with renewed purpose and the perspective of an autonomous institutional future in an independent Korean nation. These early publications include the first post-liberation issues of Penal Administration (Hyŏngjŏng), a successor to a similar colonial period penal journal that was then discontinued after the outbreak of the Korean War. Novelist Yoon Paek-nam also published a history of Korean penal culture, A History of Chosŏn Penal Administration (Chosŏn Hyŏngjŏngsa), in 1948. The work traces developments in punishment on the Korean peninsula from before the Three Kingdoms Period (57 BCE - 688 CE) through to the colonial period, and repositions the Korean people as the subject of their own penal modernization. Newspapers also served as both cheerleader and watchdog for early advances in South Korean penal administration.

With the outbreak of the Korean War, the body of available primary source material becomes sharply limited and shifts subject focus from typical penal administration to the handling of prisoners of war. The United Nations Command’s Provost Marshall section, the unit responsible for the handling of POWs and Civilian Internees (CI), kept extensive incident reports for cases of abuse, injury, and death of prisoners. The U.S. National Archives and Record Administration facility (NARA II) in College Park, Maryland holds extensive records, course materials, and correspondence related to POW reeducation programs. The same institution also holds vital materials related to wartime atrocities such as the massacres at Taejŏn Prison in the summer of 1950, and the summary execution of Sŏdaemun Prison inmates at Hongche-ri in the fall of same year.

The key primary source for analyzing post-Korean War penal development discourse is the Ministry of Justice professional journal, Penal Administration (Hyŏngjŏng). The monthly journal ran from 1952 to 1961 and featured a diverse range of articles on penal reform, musings on life as a prison guard, comics, poems, short stories, and reporting from observation tours of the penal facilities of the United States and other Cold War allies. Active penal administrators contributed to the journal and fleshed out the specifics of what it meant to “democratize” their vocation as public servants in an ostensibly democratic and developing society. This project will consider the subjectivity of prison guards (many of them veterans of the colonial prison system) in developing an autonomous penological ideal and institutional culture infused with nationalist and Cold War anticommunist ideology. Late-1950s newspapers profiled veteran prison guards, remarked on advances in penal practice since liberation, and introduced the public to the “new penology” of rehabilitation through arts, crafts and vocational training. The period also saw further development of the field of penology in international context with publications like Kwon T’ae-gŭn’s Penology (Haenghyŏnghak) in 1956. The prisoner magazine, New Path (Saegil) featured articles and creative works by prisoners for prisoner consumption, and is another vital source for understanding the specific content and messaging of rehabilitation programming. South Korean archives contain more official records and prisoner-targeted materials produced by the Ministry of Justice’s Penal Bureau, such as textbooks and approved recreational reading material, plays, and films. Further field work will also prioritize finding unofficial memoirs and eyewitness accounts of penal spaces to bring propagandistic claims of reformers and prisoner experience into the same frame of analysis. This project will also utilize interviews with former guards and inmates introduced through the network of historians associated with Seodaemun Prison History Hall.

Further archival work is needed to excavate the specific primary sources relevant to changes in prisons after Gen. Park Chung Hee’s 1961 coup d’état, but the period’s much improved administrative and records-keeping capacity make obtaining official documentation much easier than work on the Rhee regime. The largest obstacle, however, to obtaining primary sources for both the 1950s and early 1960s is the stringent nature of South Korean privacy laws that prevent archival access for materials containing the personal information of living private citizens. Thus the project will require alternative methodologies and creative use of unofficial sources to historicize the changes to penal administration in this period.

VII. Chapter Outline

The first chapter of this dissertation will reevaluate the advent of the carceral form and practice on the Korean peninsula by reviewing the scholarship on penal modernization and suggesting a more thorough Foucauldian reading of carceral practices and governmentality during the Taehan Empire (1897-1910) and Japanese colonial period. This chapter identifies the local specificities of Korea’s penal modernization, highlighting autonomous Korean discourses of reform and changes in penal culture, and merge Korean penal history scholarship with debates on the emergence of modern governmentality prior to formal annexation. This chapter will locate trends in colonial period penal discourse to better understand continuities and ruptures in the post-Liberation penal system.

The second chapter analyzes the official discourse that reframed the prison as a necessary tool for public safety divorced from its colonial legacy. It seeks to answer the question of how southern Korean prisons went from nearly empty in the Fall of 1945, to overflowing by August of 1948. It combines analysis of U.S. military archival sources with local responses to flesh out the narrative of post-Liberation penal reform and its opposition. This chapter will complicate the narrative of a seamless transition from colonial to ROK penal practice by accounting for both U.S. and local officials’ repositioning of the role of punishment under occupation and (ostensibly) autonomous Korean rule. While the infrastructure and personnel were often the same, post-liberation authorities struggled to justify the prison as a necessary institution for public safety while emphasizing qualitative difference with colonial penal practice. Popular resistance to U.S. military rule complicated official narratives about criminality and social deviance by pitting the occupation against the very people it proposed to protect. Koreans’ fight for local autonomy and survival under mismanaged economic policy landed many in jail or prison, revealing the MG criminal justice system as the repressive tool of yet another occupier. The chapter will further examine official and public discourse surrounding the state of USAMGIK prisons in comparison to their Japanese predecessors, and center high-profile cases of abuse and prison breaks following the Autumn Harvest Uprising of 1946. It will utilize the abundant primary source material (testimonies) produced surrounding the October Taegu Uprising (1946) and Cheju Massacres (1948) to account for the role of the penal apparatus in suppressing rebellion and facilitating massacre.

The third chapter will explore penal reform and ideological indoctrination, analyzing the shifting official and public discourse surrounding criminality and punishment after the founding of the Republic of Korea in 1948. The establishment of a separate government in the south further solidified division of the peninsula and raised the status of social control of deviance to that of the Cold War containment of communism. Maintaining an archipelago of well-ordered prisons (and the disciplinary power they projected to the free population) were crucial to solidifying South Korea’s internal stability as a bulwark against the spread of communism in East Asia. This chapter focuses on the penal rhetoric of president Syngman Rhee, a problematic figure with his own history of incarceration and prison activism. As one of the first administrative measures of the new republic, the Rhee regime enacted mass pardons to release a significant portion of nonviolent offenders from prison, a thinly veiled measure to remedy prison overcrowding and reduce operational costs. The problematic pardons prompted a wholesale reevaluation of the parole system and South Korean society’s belief in rehabilitation penology at large. Any relief mass pardons provided for prison overcrowding was immediately erased with the expansion of categories of political crime after the passing of the National Security Law. This chapter traces changes in the discourse surrounding “ordinary” criminality alongside the First Republic’s resurgence of colonial era methods of ideological conversion (K: chŏnhyang; J: tenkō) in penal spaces and activities of the National Guidance League. It interrogates the historiographical division between “normal” and politicized penal practice with a case study where hegemonic anticommunist ideology came to influence every facet of governance and public discourse. Analysis of materials related to the activities of the National Guidance League will emphasize the shift to a Cold War penal paradigm after the passing of the National Security Law in 1948 and flesh out the relationship between early ROK penology and ideological indoctrination.

The fourth chapter will trace developments in ROK penology and penal administration through the rupture of the Korean War. It will examine the phenomenon of massacres of political and ordinary prisoners, exploring the role of ROK penal spaces and practices in the killing. Where the previous chapter explored the discourse and rationale of pardons, this chapter examines wartime massacre of prisoners as a reversal of disciplinary power, where the status of prisoners as social deviants and the ulterior motive of conversion programs were laid bare. Prior to the outbreak of the Korean War, prisoners undergoing anticommunist conversion were housed, fed, educated and socially assimilated. After North Korean forces invaded Seoul in June of 1950, tens of thousands of ideological offenders were massacred. This chapter explores the breakdown of penal administration and resort to retributive violence towards both political and ordinary prisoners in wartime crisis. Prisons were sites of both liberation and massacre as the KPA occupied portions of South Korea in 1950. This chapter will account for the use of southern prisons by North Korean authorities, isolating the prison as a site and technology of power readymade for use by shifting polities for varied political ends.

This chapter will further explicate the influence of U.S. and United Nations penological schema on the development of rehabilitation-based penology that was infused with wartime ideological indoctrination. The UN Command’s Civilian Information and Education Section oversaw an extensive program for the “reeducation” of North Korean and Chinese POWS as well as ROK CI’s through propaganda film screenings, assigned readings produced by the United States Information Service (USIS), group discussions, and other cultural activities in the POW camps of Kŏje Island. This chapter will weave analysis of materials related to POW and civilian internment to account for changes in pre- and post-war ROK penology across a period that has heretofore only registered as a rupture in the penal historical record.

The fifth chapter will focus on the post-Korean War reconstruction of the prison system and wholesale reframing of penal administration as a tool of “democratization” and development. Nearly all of South Korea’s prison facilities were destroyed in the war. The primary aim of this chapter is to chart the significant shift in the post-war (1953-60) ROK penal imaginary that refigured the prison as a site for rehabilitation and production of the ideal democratic citizen. Spurred by technological aid from the U.S. and U.N., ROK authorities embarked on a campaign to reconstruct existing prisons, build new state-of-the-art penal facilities, and reframed their guiding ideology as a project for “democratizing” penal administration (minju haenghyŏng). Rehabilitation through education and penal labor was reframed as a mission to prepare inmates to not only rejoin society, but contribute as model citizens in an emerging member state of the Cold War’s “Free World.” This chapter will explore how South Korean penality interacted with discourses of development, modernization, poverty, and overcoming “backwardness.” It will demonstrate how discourse on the prison and deviance reflected hegemonic discourses of gender and race in the Cold War 1950s. South Korean discourses of the democratic citizen, their duties, and the human itself were significantly impacted by encounters with U.N. aid organizations and the emerging “human rights” global discourse. This chapter asks how the Cold War environment and U.S. influence racialized notions of deviance and development through the lasting impact of wartime reeducation schema that emphasized a perceived East Asian difference in the capacity for reform and achievement of liberal democratic subjectivity. South Korean penologists responded to these encounters with Western penal regimes with an urgency to overcome the “backwardness” of their system and its material limitations.

The concluding chapter concerns changes in the ROK prison system after the April Revolution of 1960 (the popular uprising that overthrew the Syngman Rhee regime) and subsequent military coup in May of 1961. Prison spaces appear in historical narratives of the initial period of repression following the fraudulent election of March, 1960, but the role of prisons in this period is understudied. The military junta (1961-63) led by Gen. Park Chung Hee fundamentally reframed the mission of penal institutions under the euphemistic schema of “corrections” by renaming penal institutions kyodoso in December of 1961. South Korean penal culture still utilizes the language and guiding ideology of corrections developed in this era.

VIII. Research Plan

My archival work in South Korea, which will start in July 2019, will be supported by the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad fellowship. While in Korea I will be affiliated with Sungkyunkwan University’s Interuniversity Center for Korean Language Studies which will provide library access and other logistical assistance. I will also work closely with one faculty member at SKKU, Professor Oh Je-yeon who specializes in contemporary Korean history and student movements of the 1950s. With Fulbright funding I will spend eight months in Seoul accessing several state archives, including the National Assembly Library, the National Library System’s central library, and the National Archives of Korea. I will also search for materials held by the Ministry of Justice Correctional Service’s central headquarters, and also explore what is made publicly available by the remaining prison facilities and archival institutions in the provinces outside of Seoul. I have also met with the director of Seodaemun Prison History Hall, Dr. Pak Kyŏng-mok, and his curatorial staff will assist me in accessing their archival materials. They also have a network of former staff and inmates from the Park Chung Hee period who periodically speak about their experience, so I have obtained the necessary credentials from UCLA’s institutional review board of the Office of the Human Research Protection Program to conduct interviews. I will return to Los Angeles in March of 2020 and support the rest of my writing process with funding as a teaching assistant. I plan to make another research trip to NARA in Maryland, as well as other U.S. archives to further flesh out the U.S. influence on Korean penology. I will then apply for the Dissertation Year Fellowship (DYF), planning to use the rest of my departmental funding and finishing my dissertation to graduate in 2022.

Sample Bibliography

Primary Sources

Newspapers and Magazines

Chosŏn ilbo

Chungang ilbo

Hyŏngjŏng

Kyŏnghyang sinmun

Saegil

Tonga ilbo

Archival Sources

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA II)

Record Group 554: Records of General HQ, Far East Command, Supreme Commander of Allied Powers and United Nations Command. USAFIK, XXIV Corps, G-2, Historical Section. “Records Regarding the Okinawa Campaign, U.S. Military Government in Korea, U.S.-U.S.S.R. Relations in Korea, and Korean Political Affairs. 1945-48.

---. Provost Marshall’s Section. Records Relating to Anticommunist Measures, Prisoners of War, and Troop Planning, 1950-51.

---. Provost Marshall’s Section. Prisoner of War Division, Correspondence Relating to Interned Korean Civilians.

RG 59 General Records of the Department of State. Central Decimal File, 1960-63. Box 2178. Country Law study for the Republic of Korea. JAG Section, HQ, Eighth U.S. Army.

“Appendix C: Reports on Korean Prisons,” Country Law study for the Republic of Korea. JAG Section, HQ, Eighth U.S. Army. 4/19/61. p. C1. NARA II, RG 59 General Records of the Department of State. Central Decimal File, 1960-63. Box 2178.

Hoover Institution Archives:

Haydon L. Boatner Papers

George F. Mott Papers

Other

American Advisory Staff, Department of Justice, USAMGIK, “Draft of Study on the Administration of Justice in Korea Under the Japanese and in South Korea Under the United States Army Military Government in Korea to 15 August 1948”

Ch’oe Se-hwang. Yŏngguk ŭi hyŏngjŏng chedo. Seoul: Ch’ihyŏng Hyŏphoe, 1954.

Gayn, Mark. Japan diary. William Sloane Associates, 1948.

Kwon, T’ae-gŭn. Haenghyŏnghak. Seoul: Kyujangsa, 1956.

Yoon, Paek-nam. Chosŏn Hyŏngjŏngsa. Seoul: Munyesŏrim, 1948.

Secondary Sources

Korean Language Sources

Ch’oe Chŏng-gi. Kamgŭm ŭi chŏngch’I. Seoul: Ch’aek Sesang, 2005.

---. Pijŏnhyang changgisu: 0.5 p’yŏng e kach’in hanbando. Seoul: Ch’aek Sesang, 2007.

---. “Haebang ihu Han’guk chŏnjaeng kkaji ŭi hyŏngmuso silt’ae yŏn’gu,” Chenosaidŭ (Genocide) Yon’gu, no. 2 (August 2007), 63-93.

Im, Chong-t’ae. Han’guk esŏ ŭi haksal: han’guk hyŏndaesa, kiŏk kwa ŭi t’ujaeng. Seoul: T’ong’il Nyusŭ, 2017.

Kang Hye-kyŏng, Che 1-konghwaguk ch'ogi kungmin t'ongje ŭi hwangnip. P'aju: Han'guk Haksul chŏngbo, 2005.

Kang Sŏng-hyŏn. “Kungmin podo yŏnmaeng, chŏnhyang esŏ kamsi, tongwŏn, kŭrigo haksal ro,” in Chugŏm ŭrossŏ nara rŭl chik'ija: 1950-nyŏndae, pan'gong, tongwŏn, kamsi ŭi sidae, edited by Kim Tŭkchung, et. al., 119-76. Seoul: Sŏnin, 2007.

---. “Han’guk chŏnchaeng chŏn chŏngch’ibŏm yangsan ‘pŏpgyeyŏl’ ŭi unyŏng kwa chŏngch’ipŏm insik ŭi pyŏnhwa,” in Chŏnchaeng sok ŭi tto tarŭn chŏnchaeng, edited by Sŏ Chung-sŏk et. al., 83-128. Sŏnin, 2011.

Kim Sam-ung, et. al. I Sŭng-man chipkwŏn'gi ŭi sŏdaemun hyŏngmŭso. Sŏdaemun hyŏngmuso yŏksagwan, 2012.

Lee Im-ha, “Han’guk chŏnjaenggi puyŏkcha ch’abyŏl,” in Chŏnjaeng sok ŭi tto tarŭn chŏnjaeng, edited by Sŏ Chung-sŏk et. al, 129-72. Seoul: Sŏnin, 2011.

Lee Jong-min, “1910-nyŏn tae kŭndae kamok ŭi toip yŏngu,” Chŏngsin Munhwa Yŏngu 22, no. 2 (Summer 1999).

---. “Cheguk ilbonŭi ‘mobŏm’ kamok: tok'yo - t'aibei – kyŏngsŏng ŭi kamok sarye rŭl chungshim ŭro,” Tongbang Hakchi 177 (2016): 271-309.

Pak Ch’an-sik, “Cheju 4.3 sakŏn kwanlyŏn haenghyŏng chalyo wa hyŏngmuso chaesoja Sŏdaemun, Map’o, Kwangju hyŏngmuso lŭl chungsim ŭlo,” Tamna Munhwa, Vo. 40, (2012): 251-315.

Pak I-jun “Migunjŏnggi chŏn'guk chuyo hyŏngmuso chiptan t'arok sagŏn yŏn'gu” Tamnon 201 9(4) (2006): 141-69.

Pak Kyŏng-mok, “Taehan cheguk malgi ilche ŭi kyŏngsŏng kamok sŏlch’i wa pon’gam/pun’gam che shihaeng,” Han’guk Kŭnhyŏngdaesa Yŏngu, no. 46 (Fall 2008): 81-104.

---. “1930 nyŏn dae Sŏdaemun Hyŏngmuso ŭi ilsang.” Han’guk Kŭnhyŏndaesa Yŏngu 66 (September 2013): 65-116.

Pŏmmubu Kyojŏng Bonbu, Taehan Min'guk kyojŏngsa, vol. 1. Paju: Pŏmmubu Kyojŏng Bonbu, 2010.

Sim, Chae-u. Chosŏn hugi kukka kwŏllyŏk kwa pŏmjoe t'ongje: ‘shimnirok’ yŏn'gu. T’aehaksa, 2009.

Song Kŏn-ho. Haebang chŏnhusa ŭi insik, vol. 1, revised edition. Seoul: Han’gilsa, 1989.

To Myŏn-hoe, Han’guk Kŭndae Hyŏngsa Chepan Chedo-sa. Seoul: P’ulŭn Yŏksa, 2014.

English Language Sources

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo sacer: Sovereign power and bare life. Stanford University Press, 1998.

Anderson, Clare. The Indian uprising of 1857-8: prisons, prisoners and rebellion. Anthem Press, 2007.

Botsman, Daniel V. Punishment and power in the making of modern Japan. Princeton University Press, 2013.

Bright, Charles. The Powers that Punish: Prison and Politics in the Era of the" Big House", 1920-1955. University of Michigan Press, 1996.

Burge, Russel. “The Prison and the Postcolony: Contested Memory and the Museumification of Sŏdaemun Hyŏngmuso,” Journal of Korean Studies, Volume 22, Number 1 (Spring 2017): 33-67.

Cumings, Bruce. The Origins of the Korean War, vol. 1. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Dikotter, Frank, and Frank Dikötter. Crime, punishment and the prison in modern China. Columbia University Press, 2002.

Dikötter, Frank. and Ian Brown. ed. Cultures of Confinement: A History of the Prison in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007).

Dudden, Alexis. Japan's colonization of Korea: discourse and power. University of Hawaii Press, 2006.

Foucault, Michel. “Truth and Power,” in Power/Knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977, ed., trans. Colon Gordon, 109-33. New York: Vintage Books, 1980.

---. Discipline and Punish: The birth of the prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

---. The Foucault effect: Studies in governmentality. University of Chicago Press, 1991.

---. "Society Must Be Defended": Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976. Vol. 1. Macmillan, 2003.

---. The Punitive Society: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1972-1973, ed. Arnold Davidson, trans. Graham Burchell. Picador, 2013.

Garland, David. Punishment and modern society: A study in social theory. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. Vol. 21. University of California Press, 2007.

Henry, Todd A. Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910–1945. Vol. 12. University of California Press, 2016.

Hwang, Kyung Moon. Rationalizing Korea: The rise of the modern state, 1894–1945. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015.

Ignatieff, Michael. A Just Measure of Pain: The Penitentiary in the Industrial Revolution, 1750-1850. Macmillan, 1978.

Kang, Jin Woong. "The Prison and Power in Colonial Korea." Asian Studies Review 40, no. 3 (2016): 413-426.

Karlsson, Anders. "Law and the Body in Joseon Korea." The Review of Korean Studies 16, no. 1 (2013): 7-45.

Kim Dong-choon. The Unending Korean War: A Social History, trans. Sung-ok Kim. California: Tamal Vista, 2009.

Kim, Marie Seong-Hak. Law and Custom in Korea: Comparative Legal History. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Kim, Monica. "Empire’s Babel: US Military Interrogation Rooms of the Korean War." History of the Present 3, no. 1 (2013): 1-28.

---. The Interrogation Rooms of the Korean War: The Untold History. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Kim, Sonja M. Imperatives of Care: Women and Medicine in Colonial Korea. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2019.

Lee Chulwoo. “Modernity, Legality, and Power in Korea Under Japanese Rule,” in Colonial Modernity in Korea, edited by Gi-wook Shin and Michael Robinson, 21-51. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

McLennan, Rebecca M. The crisis of imprisonment: Protest, politics, and the making of the American penal state, 1776–1941. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Melossi, Dario and Massimo Pavarini. The Prison and the Factory: Origins of the Penitentiary System. MacMilan, 1981.

Morris, Norval, and David J. Rothman, eds. The Oxford history of the prison: The practice of punishment in Western society. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Nisa, Richard. "Capturing the forgotten war: carceral spaces and colonial legacies in Cold War Korea." Journal of Historical Geography (2018).

O'Brien, Patricia. The promise of punishment: Prisons in nineteenth-century France. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Rothman, David. The Discovery of the Asylum: social order and disorder in the new republic. Little, Brown: 1971.

---. Conscience and convenience: The asylum and its alternatives in progressive America. Routledge, 2017.

Smith, Philip. Punishment and culture. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Thomas Lemke, Foucault’s Analysis of Modern Governmentality: A Critique of Political Reason. Translated by Erik Butler. London: Verso Books, 2019.

Mitchell, Timothy. “The Limits of the State: Beyond Statist Approaches and Their Critics.” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 85, No. 1 (Mar., 1991): 77-96.

Scott, James C. Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Weber, Max. In From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, edited and translated by H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, 77‐128. New York: Oxford University Press, 1946.

Wright, Brendan. “Civil War, Politicide, and the Politics of Memory in South Korea, 1960-1961.” PhD diss., University of British Columbia-Vancouver, 2016.

Yoo, Theodore Jun. It's madness: The politics of mental health in colonial Korea. Oakland: University of California Press, 2016.

Zinoman, Peter. The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862-1940. University of California Press, 2001.

#koreanhistory#korea#south korea#ROK#historiography#penal history#prison studies#penalhistory#incarceration#humancaging#human caging

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sociology as a Vocation in Search of Why

By Chimemerigo Princess Ilonze

Recently, in a social theory class we talked about Judith Butler’s performativity theory. A part of the discussion had to do with the use of language and how words shape experience. I found this interesting for several reasons. First, I come from a Nigerian culture that places a high value on words and names. We are a very religious and superstitious people to the point that when someone is sick, we often never admit it for fear of aggravating the illness or alerting the evil spirits lurking in the corner. People would rather say, instead, that they are “strong.”

Another reason performativity stuck with me was that in my statement of interest to get into the MUN sociology program, my beginning paragraph was autobiographical, introducing myself by the meaning of my name and how it had shaped my reality. In a way, my name created my version of sociology, my “battles” which make me constantly question my existence, the performance I put forward in the world, and the performances I receive in return. Here is a portion of my statement of interest: “My name is Chimemerigo Princess Ilonze. I’m from a tribe that holds many beliefs dear. One such belief is that a person’s name determines her or his future. So, here is what my name says about me; I am the Princess, who’s God has won (Chimemerigo) the battle among the chieftains (Ilonze). Indeed, my name, in many ways, does reflect my life.”

I was born and raised in Lagos, Nigeria, the most populous city in Africa, teeming with 21 million people. To be Nigerian is to be in constant conflict with your identity. On one end we are proud to be Africa’s largest economy, home to 250 ethnic groups and 520 languages. On the other hand, we bear the shame of our international image. Also, the Nigerian “nationality” really exists only outside of Nigeria. Internally, tribalism tears our diversity apart. My parents are from Eastern Nigeria, so I am from Eastern Nigeria; never mind that I have visited there only for a total of three weeks in my entire life. As a member of a marginalized majority tribe in the country, I am constantly at war with my identity and have always felt unwelcome at home in Western Nigeria.

All of this is not to say that I did not benefit from some privileges. In a majority black country, being fair skinned is a currency that did open several doors for me. My colorist privilege, however, does not shield me from sexism and harassment. My appearance – tall, fair-skinned and fit – was, as with most things in life, a blessing and a curse; physical, verbal and sexual harassment was common. This is, not surprisingly, the foundation of my feminism; definitely resisting the object or spectacle that I was being turned into.