#barbara wharton low

Photo

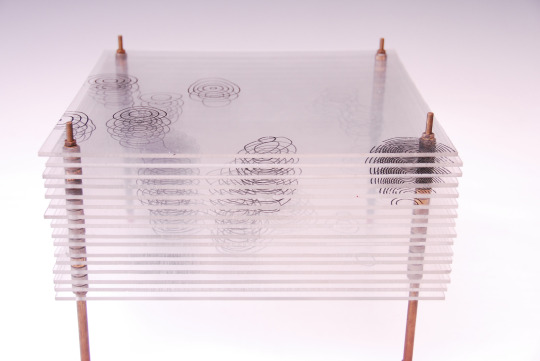

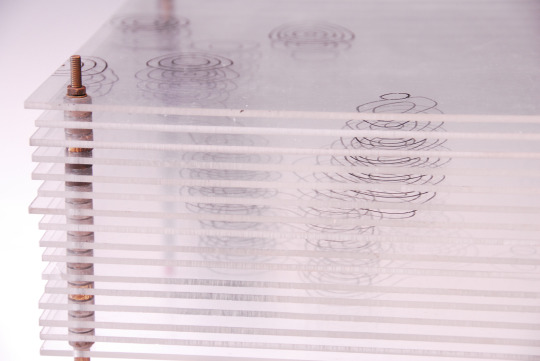

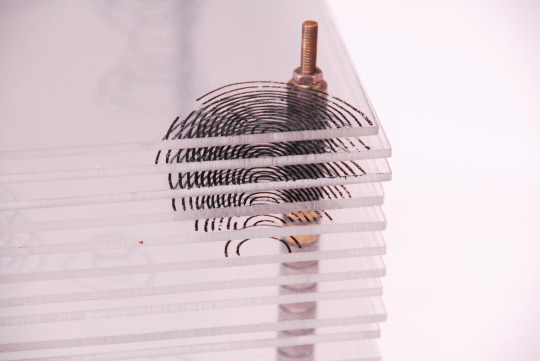

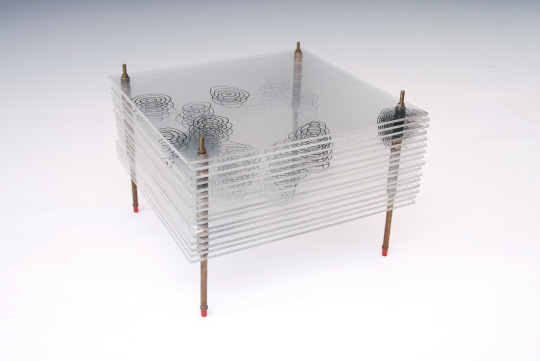

Model of the Structure of Penicillin, by Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, Oxford, ca. 1945 [Based on X-ray crystallography work by Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin and Barbara Wharton Low (Oxford) and C. W. Bunn and A. Turner-Jones (I.C.I. Alkali Division, Northwich)] [© History of Science Museum, University of Oxford, Oxford]

#chemistry#x ray crystallography#crystallography#geometry#pattern#structure#dorothy crowfoot#dorothy crowfoot hodgkin#barbara wharton low#barbara low#c. w. bunn#a. turner jones#history of science museum#1940s

129 notes

·

View notes

Photo

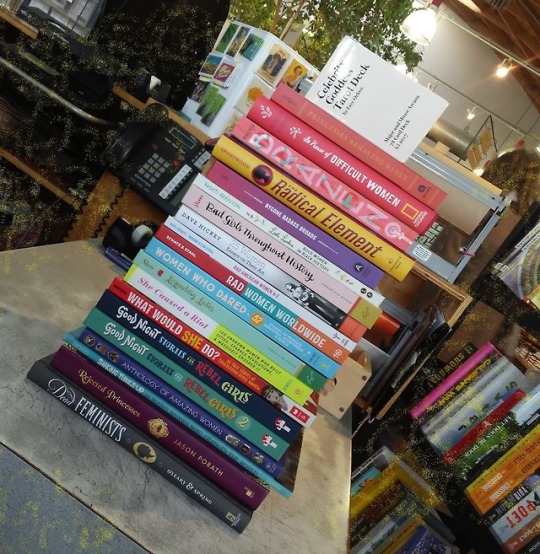

Late last night we gathered all of the new books that we carry that contain lists of

radical/difficult/legendary/badass/bold/brave/bad

girls/women/ladies/leaders/rebels/princesses/goddesses/feminists/heroines

and created a word cloud of all the names that occur in these books. Here it is in long form:

A'isha bint abi Bakr

Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer

Abigail Adams

Ada Blackjack

Ada Lovelace (appears 4 times)

Adina De Zavala

Aditi

Aelfthryth

Aethelflaed

Agatha Christie

Agnodice (appears 3 times)

Agontime and the Dahomey Amazons

Aine

Aisholpan Nurgaiv

Ala

Alek Wek

Alexandra Kollontai

Alexis Smith

Alfhild (appears 2 times)

Alfonsina Strada

Alia Muhammad Baker

Alice Ball (appears 3 times)

Alice Clement

Alice Guy-Blache

Alice Paul

Alicia Alonso

Alma Woodsey Thomas

Althea Gibson

Amal Clooney

Amalia Eriksson

Amanda Stenberg

Amaterasu

Amba/Sikhandi

Ameenah Gurib-Fakim

Amelia Earhart (appears 4 times)

Amna Al Haddad

Amy Poehler (appears 2 times)

Amy Winehouse

Ana Lezama de Urinza

Ana Nzinga

Anais Nin

Andamana

Andree Peel

Angela Davis (appears 3 times)

Angela Merkel (appears 2 times)

Angela Morley

Angela Zhang

Angelina Jolie

Anita Garibaldi (appears 3 times)

Anita Roddick

Ann Hamilton

Ann Makosinski

Anna Atkins

Anna May Wong

Anna Nicole Smith

Anna of Saxony

Anna Olga Albertina Brown

Anna Politkovskaya

Anna Wintour

Anna-Marie McLemore

Anne Bonny

Anne Hutchinson

Anne Lister

Annette Kellerman (appears 3 times)

Annie "Londonderry" Cohen Kopchovsky

Annie Edson Taylor

Annie Edson Taylor

Annie Jump Cannon (appears 3 times)

Annie Oakley (appears 2 times)

Annie Smith Peck

Aphra Behn

Aphrodite

Arawelo

Aretha Franklin

Artemis

Artemisia Gentileschi (appears 4 times)

Artemisis I of Caria

Ashley Fiolek

Astrid Lindgren

Athena

Aud the Deep-Minded

Audre Lorde

Audrey Hepburn

Augusta Savage

Aung San Suu Kyi (appears 2 times)

Azucena Villaflor

Babe Zaharias

Barbara Bloom

Barbara Hillary

Barbara Walters

Bast

Bastardilla

Beatrice Ayettey

Beatrice Potter Webb

Beatrice Vio

Beatrix Potter

Beatrix Potter

Belle Boyd

Belva Lockwood

Benten

Bessie Coleman (appears 2 times)

Bessie Stringfield

Bettie Page

Betty Davis

Betty Friedan

Beyonce (appears 3 times)

Billie Holiday

Billie Jean King (appears 3 times)

Birute Mary Galdikis

Black Mambas

Blakissa Chaibou

Bonnie Parker

Boudicca (appears 3 times)

Brenda Chapman

Brenda Milner

Bridget Riley

Brie Larson

Brigid of Kildare

Brigit

Britney Spears

Bronte Sisters

Buffalo Calf Road Woman (appears 2 times)

Buffy Sainte-Marie

Calafia

Caraboo

Carly Rae Jepsen

Carmen Amaya

Carmen Miranda

Carol Burnett

Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbuttel

Carrie Bradshaw

Carrie Fisher (appears 2 times)

Caterina Sforza

Catherine Radziwill

Catherine the Great (appears 3 times)

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

Celia Cruz

Chalchiuhtlicue

Chang-o

Charlotte E Ray

Charlotte of Belgium

Charlotte of Prussia

Cher

Cheryl Bridges

Chien-Shiung Wu

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (appears 3 times)

Chiyome Mochizuki

Cholita Climbers

Chrissy Teigen

Christina

Christina of Sweden

Christine de Pizan

Christine Jorgensen (appears 2 times)

Clara Rockmore

Clara Schumann

Clara Ward

Claudia Ruggerini

Clelia Duel Mosher

Clemantine Wamariya

Clementine Delait

Cleopatra (appears 3 times)

Coccinelle

Coco Chanel (appears 2 times)

Constance Markievicz

Cora Coralina

Coretta Scott King

Corrie Ten Boom

Courtney Love

Coy Mathis

Creiddylad

Daenerys Targaryen

Dahlia Adler

Daisy Kadibill

Dame Katerina Te Heikoko Mataira

Delia Akeley

Demeter

Dhat al-Himma

Dhonielle Clayton

Diana Nyad

Diana Ross

Diana Vreeland (appears 2 times)

Dixie Chicks

Dolly Parton (appears 2 times)

Dolores Huerta

Dominique Dawes

Dona Ana Lezama de Urinza and Dona Eustaquia de Sonza

Dorothy Arzner

Dorothy Dandridge

Dorothy Thompson

Dorothy Vaughan

Dr. Eugenie Clark

Dr. Jane Goodall (appears 3 times)

Durga

Edie Sedgwick

Edith Garrud

Edith Head

Edith Wharton

Edmonia Lewis

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor Roosevelt (appears 3 times)

Elena Cornaro Piscopia

Elena Piscopia

Elinor Smith

Elisabeth Bathory

Elisabeth of Austria

Elizabeth Bisland

Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Hart

Elizabeth I (appears 3 times)

Elizabeth Murray

Elizabeth Peyton

Elizabeth Taylor

Elizabeth Warren

Elizabeth Zimmermann

Elizsabeth Vigee-Lebrun

Ella Baker

Ella Fitzgerald

Ella Hattan

Elle Fanning

Ellen Degeneres

Elsa Schiaparelli

Elvira de la Fuente Chaudoir

Emily Warren Roebling

Emma "Grandma" Gatewood

Emma Goldman (appears 2 times)

Emma Watson (appears 2 times)

Emmeline Pankhurst (appears 3 times)

Emmy Noether (appears 3 times)

Empress Myeongseong

Empress Theodora (appears 2 times)

Empress Wu Zetian (appears 2 times)

Empress Xi Ling Shi

Enheduanna

Eniac Programmers

Eos

Erin Bowman

Estanatlehi

Ethel Payne

Eufrosina Cruz

Eustaquia de Souza

Eva Peron (appears 3 times)

Fadumo Dayib

Faith Bandler

Fannie Farmer (appears 2 times)

Fanny Blankers-Koen

Fanny Bullock Workman

Fanny Cochrane Smith

Fanny Mendelssohn

Fatima al-Fihri (appears 3 times)

Fe Del Mundo

Ferminia Sarras

Fiona Banner

Fiona Rae

Florence Chadwick (appears 2 times)

Florence Griffith-Joyner (appears 2 times)

Florence Nightingale (appears 4 times)

Frances E. W. Harper

Frances Glessner Lee

Frances Moore Lappe

Franziska

Freya

Frida Kahlo (appears 7 times)

Friederike Mandelbaum

Funmilayo Ransome Kuti (appears 2 times)

Gabriela Brimmer

Gabriela Mistral

Gae Aulenti

Gaia

George Sand

Georgia "Tiny" Broadwick

Georgia O'Keefe (appears 3 times)

Gertrude Bell

Gerty Cori

Gilda Radner

Girogina Reid

Giusi Nicolini

Gladys Bentley

Gloria Steinem (appears 3 times)

Gloria von Thurn

Grace "Granuaile" O'Malley

Grace Hopper

Grace Jones

Grace O'Malley (appears 3 times)

Gracia Mendes Nasi

Gracie Fields

Grimke Sisters

Guerrilla Girls

Gurinder Chadha

Gwen Ifill

Gwendolyn Brooks (appears 2 times)

Gypsy Rose Lee

Hannah Arendt

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Tubman (appears 6 times)

Hathor

Hatshepsut (appears 7 times)

Hazel Scott

Hecate

Hedy Lamarr (appears 5 times)

Heidi Montag and Spencer Pratt

Hel

Helen Gibson

Helen Gurley Brown (appears 2 times)

Helen Keller (appears 2 times)

Hildegard von Bingen

Hillary Rodham Clinton (appears 2 times)

Hina

Hortense Mancini

Hortensia

Hsi Wang Mu

Huma Abedin

Hung Liu

Hypatia (appears 4 times)

Iara

Ida B. Wells (appears 3 times)

Ida Lewis

Imogen Cunningham

Irena Sendler (appears 3 times)

Irena Sendlerowa

Irene Joliot-Curie

Isabel Allende

Isabella of France

Isabella Stewart Gardner

Isadora Duncan (appears 2 times)

Isis

Iva Toguri D'Aquino

Ixchel

J.K. Rowling (appears 3 times)

Jackie Mitchell

Jacqueline and Eileen Nearne

Jacquotte Delahaye

Jane Austen (appears 2 times)

Jane Dieulafoy

Jane Mecom

Jang-geum

Janis Joplin

Jayaben Desai

Jean Batten

Jean Macnamara

Jeanne Baret (appears 3 times)

Jeanne De Belleville

Jennifer Aniston

Jennifer Steinkamp

Jenny Lewis

Jesselyn Radack

Jessica Spotswood

Jessica Watson

Jezebel

Jill Tarter

Jind Kaur

Jingu

Joan Bamford Fletcher

Joan Beauchamp Procter

Joan Jett (appears 2 times)

Joan Mitchell

Joan of Arc (appears 3 times)

Jodie Foster

Johanna July

Johanna Nordblad

Josefina "Joey" Guerrero

Josephina van Gorkum

Josephine Baker (appears 7 times)

Jovita Idar (appears 2 times)

Juana Azurduy

Judit Polgar

Judy Blume

Julia Child (appears 2 times)

Julia de Burgos

Julie "La Maupin" d'Abigny (appears 3 times)

Julie Dash

Juliette Gordon Low

Junko Tabei (appears 4 times)

Justa Grata Honoria

Ka'ahumanu

Kali

Kalpana Chawla

Karen Carson

Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera

Kat Von D

Kate Bornstein

Kate Sheppard

Kate Warne

Katherine Hepburn

Katherine Johnson (appears 2 times)

Kathrine Switzer

Katia Krafft (appears 2 times)

Katie Sandwina

Kay Thompson

Keiko Fukuda

Keumalahayati

Kharboucha

Khawlah bint al-Azwar

Khayzuran

Khoudia Diop

Khutulun (appears 5 times)

Kim Kardashian

King Christina of Sweden

Kosem Sultan

Kristen Stewart

Kristin Wig

Kuan Yin

Kumander Liwayway

Kurmanjan Dtaka

Lady Godiva

Lady Margaret Cavendish

Laka

Lakshmibai, Rani of Jhansi (appears 5 times)

Lana Del Rey

Las Mariposas

Laskarina Bouboulina (appears 2 times)

Laura Redden Searing

Lauren Potter

Laverne Cox (appears 2 times)

Lee Miller

Lella Lombardi

Lena Dunham

Leo Salonga

Leymah Gbowee (appears 2 times)

Libby Riddles

Lieu Hanh

Lil Kim

Lili'uokalani

Lilian Bland (appears 3 times)

Lilith

Lillian Boyer

Lillian Leitzel

Lillian Ngoyi

Lillian Riggs

Lindsay Lohan

Liv Arensen and Ann Bancroft

Lorde

Lorena Ochoa

Lorna Simpson

Lorraine Hansberry

Lotfia El Nadi

Louisa Atkinson

Louise Mack

Lowri Morgan

Lozen (appears 3 times)

Lucille Ball

Lucrezia

Lucy Hicks Anderson

Lucy Parsons

Luisa Moreno

Luo Dengping

Lyda Conley

Lynda Benglis

Ma'at

Mackenzi Lee

Madam C.J. Walker (appears 3 times)

Madame Saqui

Madia Comaneci

Madonna (appears 3 times)

Madres de Plaza de Mayo

Mae C. Jemison

Mae Emmeline Wirth

Mae Jemison (appears 3 times)

Mae West

Mahalia Jackson

Mai Bhago

Malala Yousafzai (appears 7 times)

Malinche (appears 2 times)

Mamie Phipps Clark

Manal al-Sharif

Marcelite Harris

Margaret

Margaret "Molly" Tobin Brown

Margaret Bourke-White

Margaret Cho

Margaret Hamilton (appears 2 times)

Margaret Hardenbroeck Philipse

Margaret Sanger

Margaret Thatcher (appears 2 times)

Margery Kempe

Margherita Hack

Marguerite de la Rocque

Maria Callas

Maria Mitchell

Maria Montessori (appears 2 times)

Maria Reiche

Maria Sibylla Merian

Maria Tallchief

Maria Vieira da Silva

Mariah Carey

Marian Anderson

Marie Antoinette

Marie Chauvet

Marie Curie (appears 5 times)

Marie Duval

Marie Mancini

Marie Marvingt

Marie Tharp

Marieke Nijkamp

Marina Abramovic

Mariya Oktyabrskaya (appears 2 times)

Marjana

Marlene Sanders

Marta

Marta Vieira da Silva

Martha Gelhorn

Martha Graham

Mary Anning (appears 5 times)

Mary Blair

Mary Bowser (appears 3 times)

Mary Edwards Walker (appears 2 times)

Mary Eliza Mahoney

Mary Fields (appears 2 times)

Mary Heilmann

Mary Jackson (appears 2 times)

Mary Kate and Ashley Olsen

Mary Kingsley

Mary Kom

Mary Lacy

Mary Lillian Ellison

Mary Pickford

Mary Quant

Mary Seacole (appears 3 times)

Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft (appears 2 times)

Maryam Mirzakhani

Mata Hari (appears 3 times)

Matilda of Canossa

Matilda of Tuscany

Matilde Montoya

Maud Stevens Wagner

Maya Angelou (appears 4 times)

Maya Gabeira

Maya Lin (appears 2 times)

Mazu

Meg Medina

Megan Shepherd

Melba Liston

Mercedes de Acosta

Merritt Moore

Meryl Streep

Micaela Bastidas

Michaela Deprince

Michelle Fierro

Michelle Obama (appears 3 times)

Mildred Burke

Miley Cyrus

Millo Castro Zaldarriaga

Mina Hubbard

Minnie Spotted Wolf

Mirabal Sisters (appear 2 times)

Miriam Makeba (appears 3 times)

Missy Elliot

Misty Copeland

Mochizuki Chiyome

Moll Cutpurse

Molly Kelly

Molly Williams

Moremi Ajasoro

Murasaki Shikibu (appears 3 times)

Nadia Murad

Nadine Gordimer

Nakano Takeko

Nana Asma'u (appears 2 times)

Nancy Rubins

Nancy Wake (appears 2 times)

Naomi Campbell

Naziq al-Abid

Neerja Bhanot

Nefertiti

Nell Gwyn

Nellie Bly (appears 8 times)

Nettie Stevens (appears 2 times)

Nichelle Nichols

Nicki Minaj

Nicole Richie

Nina Simone (appears 2 times)

Njinga of Angola

Njinga of Ndongo

Noor Inayat Khan (appears 3 times)

Nora Ephron (appears 3 times)

Norma Shearer

North West

Nuwa

Nwanyeruwa (appears 2 times)

Nyai Loro Kidul

Nzinga

Nzinga Mbande

Octavia E Butler

Odetta

Olga of Kiev (appears 2 times)

Olivia Benson

Olympe de Gouges

Oprah Winfrey (appears 5 times)

Osh-Tisch

Oshun

Oya

Pancho Barnes

Paris Hilton

Parvati

Patti Smith (appears 2 times)

Pauline Bonaparte

Pauline Leon

Peggy Guggenheim (appears 2 times)

Pele

Petra "Pedro" Herrera

Phillis Wheatley

Phoolan Devi

Phyllis Diller

Phyllis Wheatley

Pia Fries

Pingyang

Policarpa "La Pola" Salavarrieta

Policarpa Salavarrieta (appears 2 times)

Poly Styrene

Poorna Malavath

Pope Joan

Portia De Rossi and Ellen Degeneres

Princess Caraboo

Princess Diana

Princess Sophia Duleep Singh

Psyche

Pura Belpre

Qiu Jin (appears 3 times)

Queen Arawelo

Queen Bessie Coleman

Queen Lili'uokalani (appears 2 times)

Queen Nanny of the Maroons (appears 4 times)

Quintreman Sisters

Rachel Carson (appears 4 times)

Rachel Maddow

Raden Ajeng Kartini

Ran

Rani Chennamma

Rani Lakshmibai

Rani of Jhansi

Raven Wilkinson

Rebecca Lee Crumpler

Rhiannon

Rigoberta Menchu Tum

Rihanna

Rita Levi Montalcini (appears 2 times)

Robina Muqimyar

Roni Horn

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Parks (appears 4 times)

Rosalind Franklin

Rosaly Lopes

Rose Fortune

Rowan Blanchard

Roxolana

Ruby Nell Bridges (appears 3 times)

Rukmini Devi Arundale

Rupaul

Ruth Bader Ginsburg (appears 3 times)

Ruth Harkness

Ruth Westheimer

Rywka Lipszyc

Sadako Sasaki

Sally Ride

Samantha Christoforetti

Sappho (appears 3 times)

Sara Farizan

Sara Seager

Sarah Breedlove

Sarah Charlesworth

Sarah Winnemucca

Saraswati

Sarinya Srisakul

Sarojini Naidu

Sarvenaz Tash

Sayyida al-Hurra (appears 2 times)

Sekhmet

Selda Bagcan

Selena

Seondeok of Silla (appears 2 times)

Serafina Battaglia

Serena Williams (appears 4 times)

Shajar al-Durr

Shamsia Hassani

Sharon Ellis

Sheryl Crow

Sheryl Sandberg

Shirely Chisolm (appears 2 times)

Shirley Muldowney

Shonda Rhimes (appears 2 times)

Simone Biles (appears 2 times)

Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Veil

Sister Corita Kent

Sita

Sky Brown

Sofia Ionescu

Sofia Perovskaya

Sofka Dolgorouky

Sojourner Truth (appears 5 times)

Solange

Sonia Sotomayor (appears 2 times)

Sonita Alizadeh (appears 2 times)

Sophia Dorothea

Sophia Loren

Sophie Blanchard

Sophie Scholl (appears 3 times)

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz (appears 2 times)

Sorghaghtani Beki

Spider Woman

Stacey Lee

Stagecoach Mary Fields (appears 2 times)

Steffi Graf

Stephanie Kwolek

Stephanie von Hohenlohe

Stevie Nicks

Subh

Susa La Flesche Picotte

Susan B. Anthony

Susan La Flesche Picotte

Sybil Ludington (appears 3 times)

Sybilla Masters

Sylvia Earle (appears 3 times)

Tallulah Bankhead

Tamara de Lempicka

Tara

Tarabai Shinde

Tatterhood

Taylor Swift

Te Puea Herangi (appears 2 times)

Temple Grandin (appears 3 times)

Teresita Fernandez

Mirabal Sisters

Muses

Night Witches

Shaggs

Stateless

Thea Foss

Therese Clerc

Tin Hinan

Tina Fey (appears 2 times)

TLC

Tomoe Gozen (appears 2 times)

Tomyris (appears 2 times)

Tonya Harding

Tove Jansson (appears 2 times)

Troop 6000

Trung Sisters

Trung Trac and Trung Nhi (appear 2 times together)

Tyche

Tyler Moore

Tyra Banks

Ulayya bint al-Mahdi

Umm Kulthum

Ursula K. LeGuin

Ursula Nordstrom

Valentina Tereshkova (appears 5 times)

Valerie Thomas

Vanessa Beecroft

Venus Williams (appears 2 times)

Victoria Beckham

Vija Celmins

Viola Davis

Viola Desmond

Violeta Parra

Virginia Apgar

Virginia Hall

Virginia Woolf (appears 3 times)

Vita Sackville-West

Vivian Maier

Wallada bint al-Mustakfi (appears 2 times)

Wang Zhenyi (appears 2 times)

Wangari Maathai (appears 3 times)

Washington State Suffragists

Whina Cooper

Willow Smith

Wilma Mankiller

Wilma Rudolph (appears 3 times)

Winona Ryder

Wislawa Szymborska

Wu Mei

Wu Zetian (appears 3 times)

Xian Zhang

Xochiquetzal

Xtabay

Yaa Asantewaa (appears 3 times)

Yael

Yani Tseng

Yayoi Kusama

Yemoja

Yennenga

Yeonmi Park

Ynes Mexia

Yoko Ono

Yoshiko Kawashima

Yuri Kochiyama

Yusra Mardini

Zabel Yesayan

Zaha Hadid (appears 2 times)

Zenobia

Zoe Kravitz

Zora Neale Hurston (appears 2 times)

#publishing#lists#women#ladies#girls#princesses#goddesses#daredevils#adventurers#broads#feminists#heroines#trailblazers

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marketing Strategy: Forever 21

From all the fun and stylish clothes you wanted as a teenager, to now a company that is filing for bankruptcy, the real question is, where did it all go wrong?

Forever 21 first started with South Korean immigrants, Jin Sook and Do Wan Chang in 1984 with an eleven thousand dollar savings from working in low-paying service jobs. As years passed, Sook and Chang took a quick turnaround and made this company grow from a 900 square foot store located in Los Angeles to an expansion of 500 stores occupying enormous amounts of space across the United States of America. By 2015, with a net worth of 6 billion dollars, Sook and Chang were definitely on their way to success.

Forever 21 is very known for wide selections of the trendy and not to mention, very cheap clothing. It gives young customers who don���t have money to spend, the advantage to get the latest looks that come out each season. So the question continues, if they are a company that was doing so great, what exactly, went wrong?

First, Forever 21 didn’t think wisely when it came to space. Wharton’s, Barbara Kahn stated that, “they weren’t seeing the trends, and instead of slowing down on physical space, they were building up physical space. That was a tactical mistake.” In a short period of time, this company was expanding rapidly and still continued opening new stores as late as 2016. Not to mention, as other companies were downsizing, they were opening outlets in seven different countries to 47 in a matter of six years.

It was also not long until technology started expanding and so did online shopping. Digital has become such an important component to retail that most stores cannot survive without it; Forever 21 didn’t prepare themselves for such a competition like this . In today’s generation, everything is about technology and convenience. If you think about it, you can get something so quickly without even having to go to the mall. Not to mention, there are also companies that are just as cheap as Forever 21, and better yet, have cuter and trendier clothes.

Forever 21 has become a fashion fail and because of this, they have taken on the sales decline stage in the Product Life Cycle. This company focused way too much on physical space and within the past two years where online marketing has grown, they still didn’t strategize correctly on making an effort to build up on their online website. Although with a target audience that is so young, it can be difficult trying to figure out what consumers want because “they’re revolting about what’s there, they want to do something new, and it’s kind of hard to figure out what their trends will be.” Through a marketing strategy, Forever 21 made a big mistake throughout the few years, thinking too fast in expanding their locations and most importantly having enormous amounts of physical space for each store. Instead they need to strategize in making smaller stores, where ultimately, they still have their trendy clothes in store in a smaller location and also not spend so much on expenses for rent. Have ship-to-store options, where people could order online and pick it up in store, where ultimately, both company and customer don’t have as high of an expense on shipping. Lastly, having overall have sustainable products and having the trendiest clothes possible.

0 notes

Text

Wharton's Barbara Kahn Gives Advice On How Retailers Can Win <b>Back</b> Customers

Wharton's Barbara Kahn Gives Advice On How Retailers Can Win Back ... excellence, low costs and efficient operations that eliminate pain points.

from Google Alert - Back Pain https://ift.tt/2rtfVeL

0 notes

Text

Are the Stock Market and the Economy Out of Sync?

The post Are the Stock Market and the Economy Out of Sync? is republished from: www.goldstonefinancialgroup.com

Goldstone Financial Group

In normal times, the stock market is often a reflection of the economy. But these are not normal times. Even though April was marked by a global shutdown of businesses, rampant unemployment and low economic growth, the S&P 500 Index ended the month up 12.9%. This represented the highest one-month gain since 1987 and posted the fastest recovery of the fastest bear-market decline in 90 years.1

It’s been a difficult time for investors, faced with the question of whether they should sell or “stay the course.” A lot depends on where you are in your timeline for achieving financial goals. You may have lost money and then regained it. You may have lost money and chose to sell. If you are near or in retirement, and unsure what you should do now, give us a call. We have many different options available to help you pursue your goals, and will help you create a financial strategy designed for your individual situation.

While the stock market and economy have an enormous influence on each other, it’s important to recognize stock prices often are driven by irrational emotions. Moreover, stock prices are forward looking, meaning they bet on future corporate profits, which do not necessarily take into account a correlation with organic growth. A good example of this was demonstrated by the 2017 corporate tax cut. Many companies used the increase in corporate earnings to buy back stocks and/or pay out dividends rather than invest in growth or worker income.

Recent volatility in the stock market is largely a result of investor optimism that the economy will survive the pandemic, followed by pessimism that it may take longer than hoped. Much of this is driven by government actions, such as the unprecedented consumer stimulus and small business “grants,” as well as the various closing and reopening phases of economies on a state-by-state basis.2

Stimulus actions may provide short-term relief, but also present a long-term drag on the economy. Reduced demand of common products and services may help ward off inflation, but the risk of deflation is just as damaging. Deflation is caused by a sustained period of falling prices, in which lower spending causes businesses to reduce staff and wages — as if that isn’t already a problem. Since consumer spending is one of the key drivers of the U.S. economy, this could lead to a long road to recovery.3

This brings us back to the stock market, with its eccentric performance that appears driven more by investor superstition, optimism and uncertainty rather than actual fundamentals. Longer term, asset prices will presumably begin to reflect the future fortunes (or losses) of corporations. It’s hard to see a scenario in which a wide swath of companies will thrive in the near term, with certain exceptions (like whichever pharmaceutical companies develop a COVID-19 vaccine).

For now, it’s important to view your portfolio within the scope of your financial goals and timeline for achieving them, as well as your risk tolerance. It’s easy to fall under the spell that a high-performing stock market will continue despite occasional blips, or that we’re in for negative returns for the foreseeable future. Regardless of which side of investor sentiment you fall on, stock market data is the same for everyone. The only differentiation is your own personal view of what will happen next.4

Meanwhile, health experts warn of a potential ramp up of contagion in states that reopen too quickly and/or in the fall when flu season commences. Given this possibility, any moves you take right now may be short-term; your view may change again if and when this actually happens. It’s possible we could have a short-term recovery, and long-term investors may want to stay in the market for exposure to that. But no one can accurately predict when the stock market could drop precipitously again, so bear that in mind.5

Content prepared by Kara Stefan Communications.

1 John Persinos. Investing Daily. May 4, 2020. “Economy Down, Stocks Up: Why The Disconnect?” https://www.investingdaily.com/55655/economy-down-stocks-up-why-the-disconnect/. Accessed May 5, 2020.

2 Barbara Kollmeyer. Marketwatch. May 5, 2020. “This is the trap awaiting the stock market ahead of a grim summer, warns Nomura strategist.” https://www.marketwatch.com/story/this-is-the-trap-awaiting-the-stock-market-ahead-of-a-grim-summer-warns-nomura-strategist-2020-05-05. Accessed May 5, 2020.

3 Paul Davidson. USA Today. May 3, 2020. “Besides millions of layoffs and plunging GDP, here’s another worry for economy: Falling prices.” https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2020/05/03/coronavirus-us-deflation-falling-prices-new-economic-risk/3070084001/. Accessed May 5, 2020.

4 Knowledge@Wharton. Jan. 14, 2020. “How Superstition Triggers Stock Price Volatility.” https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/wachter-superstitious-investors-research/. Accessed May 5, 2020.

5 Matt Egan. CNN. April 16, 2020. “The stock market is acting like a rapid recovery is a slam dunk. It’s not.” https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/16/investing/stock-market-dow-jones-recession/index.html. Accessed May 5, 2020.

We are an independent firm helping individuals create retirement strategies using a variety of insurance and investment products to custom suit their needs and objectives. This material is intended to provide general information to help you understand basic financial planning strategies and should not be construed as financial or investment advice. All investments are subject to risk including the potential loss of principal. No investment strategy can guarantee a profit or protect against loss in periods of declining values.

The information contained in this material is believed to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed; it is not intended to be used as the sole basis for financial decisions. If you are unable to access any of the news articles and sources through the links provided in this text, please contact us to request a copy of the desired reference.

1184249C

0 notes

Text

Which is the best place to study an MBA, the UK or US?

Are you confused about which destination to choose from the best study abroad destinations? US and UK being the top two study abroad destinations always attract lots of international students. But there are many questions which you must be looking for. e.g. what is the difference between

MBA in USA vs UK

? Which of the two will suit your requirements the best? Whether studying MBA in USA will help you to grab that dream job or Studying MBA in UK will be more beneficial? Which one encourages international students more? Where I will be able to afford to pursue my dream course?To help you to choose the best destination for you, we are going to evaluate 8 parameters in this article. So, read on to know the facts and take a rational decision about MBA in USA Vs UK.MBA in USA Vs UK

World Ranking and Quality of Education

Eligibility Criteria

Job Prospects

Style of Education

Simplified Visa Processes

Lifestyle

Cost of Living

Life After MBA

World Ranking and Quality of EducationBoth the countries provide the best in class education and thus attract lots of International students. If we go by the ranking the USA has more universities in the list of top 10 universities of the world. Hence, USA is the most preferred destination of the international students.US offers a diverse range of options to international students to explore from and decide about what suit them the best. An International student can aim to study from ivy-league schools like Harvard & Stanford to outstanding public colleges like Santa Barbara City College. These institutes are not only diverse in their culture but also tuition

Business Resources and Information.

is known to provide best infrastructure, latest technology and equipment to the students.

In UK, you will find a unique amalgam of historic academic excellence from Oxford, Cambridge, LSE and the latest technology available at the new campuses like Brunel University. Eligibility criteria is very important to check the eligibility criteria. Though the eligibility requirements may vary from university to university but the general norms followed are:-Eligibility for USAMin. 4 years education after 10+2 (some colleges do accept 15 years of education)Eligibility for UK3-year graduation accepted GMAT ScoreUSA- 720 – 730UK-680 – 690Work experience USA- 3 – 6 years UK- 2 – 4 years, you need to check the individual website of the universities you are planning to apply for. Checking eligibility criteria is very important as you should know whether you are eligible to study in Study in USA Vs UK. As there are some B-Schools in US that do not require work experience but the top B-Schools want you to have at least 3-6 years of work experience. Also, there are some good B-Schools which accept 15 years of education in US.List of the Top B-Schools Which Accept 15 Years of Education:

University of Virginia Darden School of Business

Dartmouth University Tuck School of Business

University of Pennsylvania Wharton School

NYU Stern School of Business

MIT, Sloan School of Management

Duke University Fuqua School of Business

University of Chicago, Booth School of Business

Northwestern University, Kellogg School of Management

Columbia Business School

Yale School of Management

There is always room for some flexibility so a candidate should check with the concerned department if there is any confusion about the eligibility criteria.Job ProspectsMost of us want to go for study abroad for better job prospects after studying. So, which country will offer you better opportunities after MBA?Chances of Employment for U.K. - FairChances of Employment for U.S.A. - GoodWork Permit for U.K. - FairWork Permit for U.S.A. - EasyChances of employment after you Study MBA in the USA are attractively high. On the other hand, the chances of employment in UK are also decent enough and you can apply for the work permit after MBA but it is at times restricted to two years. With the change in policies it has become easier to get the work permit in USA.Style of EducationThe style of education in both the counties is very different. In USA, the learning system is wide and varied. The students are encouraged to go for optional subjects beyond the curriculum of their major. The focus is on the breadth of learning.On the other hand, if you Study MBA in UK you will be required to focus on the subject area you have opt for and you are expected to gain thorough knowledge of the subject through classroom teachings. The focus is on the in-depth study of the subject area.Simplified Visa ProcessesIt is extremely difficult to get admission into the world’s best universities, no matter which country they are located in. But to get admission into the best American schools is even harder. The competition is hard and the acceptance rate for international students is quite low. Also, the visa requirements are tough and all this requires lot of energy and time if you want to study in American Universities.The visa and application process in UK has been streamlined and made easier for the benefit of the students. The drawback of the same is that there are more number of applicants per seat and that makes the competition tougher.LifestyleBoth the countries are multi-cultural with students coming from all across the globe. They provide full support to the international students so that they feel at home and develop as a whole in a new environment.If you love to explore places which are rich in history and culture with the green countryside, UK is the place you should be looking for.The USA also has something in store for all; there are different climate ranges, fast moving cities and easy-going suburbs.Cost of LivingThe cost of living in both the countries is on the higher side when compared to the India’s cost of living. When compared the cost of MBA in USA Vs UK, the cost of studying MBA in USA is higher than that of the cost of studying in the UK. The tuition fee is much higher in USA universities. For US, fees can go up to 1 crore; whereas in UK it would be under 60 Lakhs.Also, one can complete an MBA degree program in one year from the UK whereas in the USA, you have to spend two years to earn an MBA degree.Life After MBAWhat you want to do after you complete your MBA is another important decision factor.

If you want to stay back after your MBA, USA is a better option as you can get unconditional employment in USA. Though getting a job is not that easy. On the other hand in UK, the international students doing MBA can get a work permit of limited time period of two years only once they get a job.

With an MBA from the UK, it is also possible to get employment opportunities in Europe.

If you wish to come back and work in your own country, then choose the one which suits your pocket, time and temperament.

So, when you are deciding about whether to go for MBA in USA Vs UK, just answer the below questions to yourself and analyze your answers to choose what is best for you.

Will it help you to rise up the career ladder?

Does your own country recognize the program and university you are planning to apply for?

Do you want to study in-depth about a particular subject or you want to go for the variety of subjects.

Which option is more pocket-friendly?

Do you fulfill the visa requirements and other criteria?

Thus, it is always better to take a rational decision after evaluating all the major factors. You can always take expert’s guidance by connecting with us through 24×7 guidance services provided at our website. We are always happy to help our students! We love to see them chasing and then living their dreams in reality.Credit:

Study in London MBA for International Students

0 notes

Link

VA Loans in Santa Maria Texas

Contents

Texas home health jobs

Fee applies. property insurance

Loan center (rlc

Native americans roughly 13

Whether you're buying a new home or refinancing, Homebridge is your trusted home mortgage lender to help you find the right loan – FHA, First Time Home.

VA Loans in Whitehouse Texas VA Loans in Smiley Texas VA Loans in Wharton Texas VA home loans. ROSENBERG, Texas, United States. 11C Indirect Fire Infantryman.. Sponsored by National Guard – save job.. Be the first to see new texas home health jobs in Wharton, TX. My email: Also get an email with jobs recommended just for me. Company with Texas Home Health jobs.VA Loans in Wolfe City Texas Get help planning a burial in a VA national cemetery, order a headstone or other memorial item to honor a Veteran’s service, and apply for survivor and dependent benefits. Careers and employment Apply for vocational rehabilitation services, get support for your Veteran-owned small business, and access other career resources.A 0.00% origination fee applies. property insurance is, and flood insurance may be, required. Other rates and terms available. Additional restrictions apply to Texas home equity loans. VA loans require a VA funding fee collected at closing. The fee varies with the amount of the down payment and is higher with no or low down payments.VA Loans in Sunset Texas A VA loan is just the type of loan, you still need to be approved for a loan for it to be backed by VA. VA Loans in Timpson texas local loan Limits – Timpson, TX Loan limit summary. limits for FHA Loans in Timpson, Texas range from $314,827 for 1 living-unit homes to $605,525 for 4 living-units.

At Lendmark Financial Services, we understand loans are as individual as the people who apply for them. We personalize loan solutions to meet your unique needs, but one thing is always the same for every Lendmark customer: we strive to make borrowing easy, convenient, and affordable.

American Mortgage Lenders has been opened in Santa Maria, Ca. since 1998. Our experienced staff has over 100 years of combined Mortgage lending experience. American Mortgage Lenders, Inc. is a locally owned company that is ready to help with your mortgage needs and typically gets you approved in a few short minutes.

VA Loans in Whitney Texas VA Loans in Willamar Texas Houston Regional Loan Center Our Services. The houston regional loan center (rlc) is one of eight VA regional loan centers (RLCs) administering VA’s Home loan guaranty program, which helps veterans obtain mortgage loans from private lenders by guaranteeing a portion of the loan against loss.VA Loans in Winona Texas VA Loan Limits : 2019 Current VA Limits for TEXAS Counties. Although VA guaranteed loans do not have a maximum dollar amount, lenders who sell their VA loans in the secondary market must limit the size of those loans to the maximums prescribed by GNMA (Ginnie Mae) which are listed below.

Nutmeg State also announced Working Wheels, an auto loan program designed. Union ($840 million, Austin, Texas) in 2020. In addition, PSCU announced Chartway Federal Credit Union ($2.2 billion,

Santa Barbara County, California VA Loans. The 2018 $0 down; VA home loan limit for Santa Barbara County is $625,500. Located along the Pacific Coast in Southern California, the area of modern day Santa Barbara County was settled by native americans roughly 13,000 years ago.

The VA loan isn’t just for San Antonio homebuyers: Eligible homeowners in Texas have several options for refinancing using the VA loan program. The VA Streamline Refinance (also known as an Interest Rate Reduction Refinance Loan, or IRRRL) allows qualified VA homeowners to reduce their interest rate.

VA Loans in Southmayd Texas Home Loans In Voca, Texas licensing info: nmls # 317299. rmlo # 222329 "consumers wishing to file a complaint against a company or a residential mortgage loan originator should complete and send a complaint form to the texas department of savings and mortgage lending, 2601 north lamar, suite 201, austin, texas 78705.

Get help planning a burial in a VA national cemetery, order a headstone or other memorial item to honor a Veteran’s service, and apply for survivor and dependent benefits. Careers and employment Apply for vocational rehabilitation services, get support for your Veteran-owned small business, and access other career resources.

Kositzka, Wicks and Company – This Alexandria, Va.-based accounting. allegedly sent this Santa Ana-based bank, called “Lender C” in his indictment, doctored and falsified financial documents to try.

About Home Loans. VA Home Loans are provided by private lenders, such as banks and mortgage companies. VA guarantees a portion of the loan, enabling the lender to provide you with more favorable terms. Your length of service or service commitment, duty status and character of service determine your eligibility for specific home loan benefits.

The post VA Loans in Santa Maria Texas appeared first on VA Loans Arlington TX.

https://ift.tt/2ZGHY8N

#Arlington VA Home Loan#VA Home Loan Requirements in Arlington#Arlington VA Loan Rates#VA Home Loan R

0 notes

Text

‘Stable genius’ Trump has spent decades fixating on IQ

New Post has been published on https://thebiafrastar.com/stable-genius-trump-has-spent-decades-fixating-on-iq/

‘Stable genius’ Trump has spent decades fixating on IQ

“Sorry losers and haters, but my I.Q. is one of the highest -and you all know it! Please don’t feel so stupid or insecure, it’s not your fault,” Donald Trump tweeted in 2013. | Alex Wong/Getty Images

white house

People who know Trump suspect his IQ obsession stems in part from a desire to project an image of success, despite scattered business failings and allegations of incompetence.

It was January 2004 and Donald Trump was on the “Today Show” to promote a new reality TV series called “The Apprentice.”

Almost immediately after the interview began, Trump started bragging about the unparalleled intellect of the contestants who would compete for a job at one of his companies.

Story Continued Below

“These are 16 brilliant people. I mean, they have close to 200 IQs, all of them,” he told Matt Lauer. “And some may be beautiful and some may not be beautiful. But everybody has an incredible brain.”

It wasn’t the first time Trump fixated on IQ as a measure of a person’s worth — or, as is frequently the case, worthlessness. And it wouldn’t be the last. Fifteen years later, Trump, now the president of the United States, still uses IQ as a shorthand for intelligence, dividing the people in his orbit into winners and losers.

In private, according to interviews with a half-dozen people close to him, Trump frequently asserts that people he likes have genius-level IQs. At various points during his presidency, he’s told aides that Lockheed Martin CEO Marillyn Hewson and Apple CEO Tim Cook are high-IQ individuals, for example, former White House officials said. Trump has also dubbed himself a “very stable genius” on multiple occasions.

And the president is quick to accuse his political enemies of having low IQs, as he did when he repeated North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un’s criticism of former Vice President Joe Biden, one of his leading Democratic challengers.

“I was actually sticking up for Sleepy Joe Biden while on foreign soil. Kim Jong Un called him a ‘low IQ idiot,’ and many other things, whereas I related the quote of Chairman Kim as a much softer ‘low IQ individual,’” Trump said Tuesday after the Biden campaign criticized him for tweeting during his trip to Japan that he smiled when Kim insulted Biden’s intelligence.

While the exact reason for Trump’s IQ obsession is difficult to nail down, people who know him suspect it stems in part from his desire to project an image of success and competence, despite scattered business failings and repeated allegations from critics that he’s incompetent. Trump is also known for being thin-skinned. He often fires back at anyone who criticizes him with a barrage of insults, while simultaneously building himself up.

“I don’t think you have to put him on the couch to see that someone who has such a consistent need to build himself up and belittle everyone else must have some problems with self-esteem,” said Trump biographer Gwenda Blair, who wrote a book about the Trump family. “It’s a lifelong theme for him.”

“Part of it comes from his insecurities about not being perceived as intelligent,” a former White House official added.

In recent years, Trump has accused Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.), actor Robert De Niro, Washington Post staffers, former President George W. Bush, comedian Jon Stewart, Republican strategist Rick Wilson, MSNBC host Mika Brzezinski, and Rick Perry, now his energy secretary, of having low IQs.

He once suggested he’d like to compare his IQ to that of then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, adding, “And I can tell you who is going to win.” He privately mocked former Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ intelligence, according to a former White House official. All the while, Trump has claimed his Cabinet has the highest IQ of any assembled in history.

“Sorry losers and haters, but my I.Q. is one of the highest -and you all know it! Please don’t feel so stupid or insecure, it’s not your fault,” Trump tweeted in 2013.

Just last week, the president again referred to himself as an “extremely stable genius,” and he has spent years insisting has a high IQ score, though he has never revealed the exact number. When a Twitter critic challenged him in 2013 to prove his high IQ, Trump responded simply, “The highest, asshole!”

Democrats are increasingly fed up with Trump’s name calling, encouraging journalists to ignore it altogether and arguing it’s a sign that the president isn’t serious about policy or governing.

Trump has been obsessing over IQ and pedigree for decades, long before he moved to the White House. Barbara Res, a former Trump Organization official, recalled that Trump used to brag about one of his executives graduating from Yale Law School at the top of the class, even though Yale Law doesn’t rank its students. Trump later made the same false assertion about Brett Kavanaugh.

“He always used to say that he had a very high IQ,” Res added, recalling her decade-plus working alongside him.

Trump’s black-and-white view of intelligence was formed long before psychologists embraced a more nuanced definition of the term. In 1983, for example, developmental psychologist Howard Gardner put forward his theory of multiple intelligences, which stressed that people learn in many different ways and suggested IQ tests were too narrow.

“Measuring someone’s intelligence is not simply a matter of taking one test with a sharpened No. 2 pencil. Donald Trump came of age before that whole notion, for sure,” Blair said. “He’s still thinking in terms of that No. 2 pencil.”

Recently, however, IQ measurement has found increasing resonance among alt-right and white supremacist groups, who have linked IQ and race to argue for limits on immigration from certain ethnic groups.

Trump, who attended the Wharton School of business at the University of Pennsylvania, has an affinity for people who graduated from prestigious universities.

He warmed up to his former staff secretary, Rob Porter, once he learned that Porter attended Harvard University and was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, according to two people familiar with the matter. “This guy is so smart,” he’d sometimes tell other staffers of Porter. “He was a Rhodes Scholar!”

He was similarly impressed with the credentials of his two Supreme Court picks: Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch. The president has regularly touted their Ivy League educations in conversations with allies, and White House aides believe attending a top-tier law school is one of Trump’s prerequisites for any future nominee to the high court.

Trump has also frequently mentioned his late uncle, a former physics professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, calling him “a great, brilliant genius,” last year.

But Trump himself has long been reluctant to reveal any details about his own schooling. Trump’s longtime fixer Michael Cohen told lawmakers in February that his boss regularly instructed him to pressure the reality TV star’s alma maters with letters warning of jail time if they released Trump’s grades.

“I’m talking about a man who declares himself brilliant, but directed me to threaten his high school, his colleges and the College Board to never release his grades or SAT scores,” Cohen told the House Oversight Committee.

The White House press office did not respond to a request for comment, nor did it respond to an inquiry about Trump’s IQ score.

The president’s elitism stands in stark contrast to the central messages of his campaign, which promised to upend establishment Washington and sought to appeal to disaffected white working class voters. But Trump’s advisers say the dichotomy works in his favor, arguing that the president’s business experience and lavish lifestyle is one of the things that makes him appealing to his base.

“He’s a populist in a way, but he’s a populist only in terms of his policies,” said another former White House official. “His personal message has always had a real elitist flavor to it.”

Daniel Lippman contributed to this story.

Read More

0 notes

Text

Retailers try to lure customers with free Uber rides

NEW YORK — While shoppers are getting everything from morning coffee to complete work wardrobes delivered to their homes, some businesses are working with ride-hailing company Uber to entice customers through their doors.

Uber launched a voucher program Tuesday that enables companies like Westfield Mall and TGI Fridays to dole out free or discounted rides to customers, offering a way for retailers to counter declining foot traffic heightened by the growth of online shopping.

Retail traffic has declined 2.3% over the last two years, according to Cowen Equity Research. Malls in particular have experienced a drop-off as younger generations living in urban centres have shown little interest in owning cars and taking trips to suburban shopping malls, said Jon Reily, vice-president and global commerce strategy lead at Publicis Sapient. The growing number of retail bankruptcies illustrates the problem, he said.

“That’s a great move for malls to get people in the door, because malls need footfall, and anything that they can do to get that is a good thing,” Reily said.

Restaurants are also participating in the Uber vouchers, including some that are already delivering food to customers’ homes through Uber Eats.

Getting diners back into the restaurant — even if it means paying for their ride — could enable restaurants to make more money since customers could be more inclined to order a dessert or an alcoholic beverage or two than if they ordered delivery to their homes.

Alcohol is a money-maker for restaurants, and delivering happy hour margaritas or cocktails in an Uber car isn’t a viable option. Uber does deliver alcohol from a very limited number of restaurants, but it is not available to most customers.

“Our bartenders might hand these out as a way to ensure we’re providing a great guest experience,” said Sherif Mityas, chief strategy officer at TGI Fridays.

The vouchers — like coupons — could be given out as a perk to rewards members, creating another visit that might not happen otherwise, Mityas said.

In recent months Uber has been working with hundreds of companies to test the program, including entertainment providers such as concert promoter and venue operator Live Nation, basketball team the Golden State Warriors and MGM Resorts. The program is now more widely available to business in the majority of cities where Uber operates.

Participating businesses pay for the rides and set the terms, deciding whether to offer free or discounted rides and any time limitations, and they distribute the vouchers as they see fit. They send customers a link to the voucher through email or their own apps, and when customers accept the voucher it will be loaded into the Uber app.

“Consumers today are really demanding that convenience,” said Brittany Wray, strategic partnerships lead for Uber for Business. The vouchers enable businesses to offer a better customer experience by taking care of the hassle of getting to and from the physical location, she said.

Uber’s new product illustrates a paradigm shift in retailing where businesses are focused on customer experience instead of the product, said Barbara Kahn, professor of marketing at The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

One way to compete with Amazon’s low prices and convenience is to offer a really good in-store experience, and “in order to do that, you do have to bring people into the mall,” Kahn said.

from Financial Post http://bit.ly/2P2AMjQ

via IFTTT Blogger Mortgage

Tumblr Mortgage

Evernote Mortgage

Wordpress Mortgage

href="https://www.diigo.com/user/gelsi11">Diigo Mortgage

0 notes

Text

Online Shopping: The Complete Wired Guide

New Post has been published on http://webhostingtop3.com/online-shopping-the-complete-wired-guide/

Online Shopping: The Complete Wired Guide

Type “cheesecloth” into Google shopping. Hundreds of online shopping options pop up, in more than a dozen shades, at a range of price points. Many of the packages can be shipped to you in two days or less. In other words, shoppers live in a golden age of convenience. We’ve got more access to more stuff than ever before, at cheaper prices and ever-more-instant speeds. And the businesses who hawk us that stuff? They’ve got unprecedented levels of data on us, and they’re using it to target us in ever-more personalized ways.

As Americans, shopping’s in our bones. Patriotic fervor practically elevated consumerism to a religion after World War II, and today, we blur Jesus and Santa, ditch Thanksgiving for Black Friday, and mint new holidays (Cyber Monday) that give way to copycat holidays (Prime Day), all dedicated to buying stuff. Consumer spending on the “goods” portion of goods and services powers roughly one quarter of the economy, so it follows that retail is uber-susceptible to the technological, political, and economic forces that shape our society. Long ago, traveling peddlers were displaced by local merchants, who were supplanted by downtown department stores, which were upended by shopping malls, then big box chains, and now, the internet. And technology has armed today’s retailers with powerful tracking tools: We accept user agreements and pop-ups, trading gobs of valuable personal data in exchange for convenience—a commodity almost as prized as shopping itself.

The History of Online Shopping

The age of internet commerce really kicked off with Sting. Back in 1994, a band of coders led by a 21-year-old Swarthmore grad named Dan Kohn lived together in a two-story Nashua, New Hampshire, house. Fueled by ambition and a roaring Coca-Cola habit, they launched an online marketplace called NetMarket. The site let users make secure purchases by downloading encryption software named PGP, for “Pretty Good Privacy.” At noon on August 11, a Philadelphia man named Phil Brandenberger logged on. Typing in his address and credit card number, he bought a CD of Sting’s “Ten Summoners’ Tales” for $ 12.48 plus shipping. Champagne corks flew. The New York Times called it the first secure purchase of its kind. “Attention Shoppers,” a headline announced. “The Internet Is Open.”

Years later, Randy Adams, CEO of another online store called the Internet Shopping Network, claimed to have beaten out Kohn’s group by a month. In either case, the ecommerce floodgates didn’t quite fly open. The Unix-based programs required some tech know-how, and computers were a lot slower back then.

While we wait for modem speeds to rev up from bits to megabits, then, let’s review some retail history. Back in the ’80s, shopping largely centered around malls. Post–World War II migration to the ‘burbs had gutted downtown shopping centers and the sprawling department stores that served as their nuclei. Tax breaks and car culture spurred mass development of new big box stores and suburban shopping malls, and these parking-flush spaces recreated sanitized versions of urban retail corridors, writes Vicki Howard in From Main Street to Mall. Giant discount shops devoured local mom and pops. By 1990, Walmart had become the nation’s largest retailer.

Consumers were spoiled for choice, and they could get it on the cheap. But big box shops were laid out to maximize in-store time, turning shopping into a time-gobbling, endurance event. In the 2003 comedy Old School, Will Ferrell’s character Frank the Tank played this suburban ritual for laughs: “Pretty nice little Saturday, actually, We’re going to go to Home Depot…Maybe Bed, Bath, & Beyond, I don’t know. I don’t know if we’ll have enough time!”

Online shopping, by contrast, offered the promise of near-limitless choice at relatively snappy speeds. One of the earliest pre-Internet shopping ventures to test the online waters, CompuServe’s “Electronic Mall,” opened in 1984, offering stuff from more than 100 merchants, from JC Penney to Pepperidge Farms. Next to today’s sleek web pages, CompuServe’s command line interface looks positively primitive. But it worked, and it saved a trip to the mall. (As one early adopter told his local newscaster: “I just don’t like crowds.”) When it opened, only eight percent of US households had a computer, and at dial-up rates starting at around $ 5 an hour, the mall enjoyed limited success. E-shopping was still a decade away from going mainstream.

youtube

In 1988, a CompuServe competitor named Prodigy sprung up, the product of a partnership between Sears and IBM. Alongside news, weather, email, banking, and bulletin boards, the service included a store. Jaunty illustrations accompanied item descriptions, but as Wired noted in 1993, “the service’s cartoon-like graphics proved far less useful to purveyors of items that consumers wanted to see before buying, such as clothing and home furnishings.” A short-lived grocery service folded “because consumers were uncomfortable using a PC to select food.”

Until the World Wide Web debuted publicly in 1991, online shopping remained the province of services like Prodigy. That year, the National Science Foundation, which funded the networks that made up the backbone of the Internet, lifted its ban on commercial activity. Merchants were free to register domains and set up cybershop, but a problem lingered: Shoppers were—rightly—suspicious of handing over credit card data to remote, faceless webmasters. No mechanism existed to verify the sites’ authenticity.

In December 1994, a 23-year-old University of Illinois grad named Marc Andreessen released Netscape 1.0. The web browser featured a protocol called Secure Sockets Layer (SSL), which let both sides of a transaction encrypt personal information. From there, ecommerce began to take off.

Without the cost of maintaining physical stores, online retailers could offer lower prices and larger assortments than their brick and mortar counterparts, and people could by them in less time than it took to gas up the minivan. A “nice little Saturday” no longer had to entail epic marathons to warehouse-style superstores. If Sting knocked on the floodgates, Amazon was the wave that was about to burst them open.

In July 1995, a hedge fund VP named Jeff Bezos opened an online bookstore. He named it after the world’s largest river, after deciding against Relentless.com. (The domain still redirects to Amazon.) The site carried a million titles, and Bezos billed it “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore.” Within a month, Amazon.com had sold books to buyers in every US state, plus 45 countries.

Bezos recognized that shopping online at the time carried so-called pain points. Gauging quality could be difficult. Shoppers had to manually enter lines and lines of payment and shipping info each time they wanted to buy a nut sampler. High shipping costs could cancel out savings. Such headaches led shoppers to abandon their carts at distressing rates.

Amazon knew these minor irritations could add up, spelling major revenue losses. From the beginning, “Bezos was maniacally focused on the customer experience,” says retail expert and Wharton professor Barbara Kahn. No more cartoonlike graphics: Books were fully digitized, and shoppers could flip through the pages like they could in a physical store. Books were searchable by title, browsable by category, and readers could post reviews. In 1999, Amazon famously patented one-click ordering. This seemingly minor innovation slashed shopping cart abandonment, convinced customers to fork over their data, and helped cement Amazon as the go-to one-stop-shop for hassle-free shopping. Shipping got faster and cheaper, becoming free for orders above $ 99 in 2002, then for all Prime members in 2005.

Sites like Amazon and eBay, which also opened in 1995 as “AuctionWeb,” proved you didn’t need a physical store to give customers what they wanted. A lot of what they wanted. In 1999, Zappos (since acquired by Amazon) opened one of the first online-only shoe stores, enticing shoppers with free shipping, a generous (and free) return policy, and legendary customer service (one call famously lasted ten hours). The internet promised riches, and investors exuberantly, sometimes irrationally, supplied the funding.

Not every digital store survived that first boom. Cash-flush e-tailers like pets.com and grocery deliverer WebVan poured millions into ad campaigns, expanding rapidly before realizing that customers didn’t always want what they offered. Less than a year after the pets.com mascot soared over Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade, the company learned that plenty of pet owners in the already crowded space didn’t mind picking up dog food and kitty litter from the grocery store, especially if that meant avoiding shipping costs and long waits. The company closed in 2000. Not long after erecting state-of-the-art fulfillment centers in ten cities, WebVan discovered that the cost-conscious shoppers they targeted weren’t ready for what amounted to an upmarket service: Customers didn’t spend enough to subsidize the trips; they preferred coupons and economy sizes, which WebVan didn’t offer; they often weren’t home during the short delivery windows. The grocery business’s paper-thin margins provided little room for error, and the company declared bankruptcy in 2001, near the height of the dot-com crash. These failures, however, would become instructive for the next generation. “Get Big Fast” gave way to “Minimum Viable Product.”

The Latest Shopping Tech

Stock Bots

Walmart partnered with Bossa Nova Robotics to deploy inventory-tracking droids in 50 stores this year.

Virtual Showrooms

Hardware giant Lowe’s debuted its “Holoroom” last year, which guides headset-clad DIYers through home improvement projects in VR.

Face Time

Gourmet confectioner Lolli & Pops recently installed facial recognition cameras in stores to flag regulars and compile customized shopping recommendations.

Mirror, Mirror

Fashion retailer Farfetch unveiled touchscreen mirrors and clothing racks that sense when an item is removed—then beam a virtual version to the shopper’s smartphone.

Cinderella Scanners

New Balance and Fleet Feet Sports recently introduced scanners by Volumental that generate a 3D virtual model of your feet in five seconds. An AI algorithm extracts 10 measurements, from length to arch height, to recommend a perfectly fitting shoe. No disposable sock required.

Swipe and Shop

Through Instagram’s new shopping feature, users can tap stickers on Stories to display merchandise details and shopping links. The Facebook-owned social media platform is reportedly developing a standalone shopping app.

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, “digitally native vertical brands” (DNVBs) like Bonobos (menswear) and Warby Parker (eyewear) spun up their own direct-to-consumer models. By controlling the entire process from factory to sale and reaching consumers directly through websites and social media channels, these brands could keep prices down, collect extensive data on their customers, and test new products. Last year, DNVBs grew three times faster than ecommerce as a whole. The more data companies swallowed up, the better they got at personalizing their recommendations. They burrowed their way into our inboxes and onto our social media pages. Their algorithms knew what we wanted and predicted what we were going to want. It started to seem like brick and mortar didn’t stand a chance.

Indeed, by the mid-2010s, tax breaks and a hunger for growth had led US retailers to build stores at rates that eclipsed Europe and Japan by a factor of six. This “over-storing,” combined with ecommerce competition, set the stage for the so-called “retailpocalypse.” In 2017, an estimated 7,800 US stores shuttered, and 3,600 were forecast to close in 2018.

If big box stores were going to survive, they needed to reinvent themselves. Consumers had grown to expect all the convenience, selection, and low prices of online shopping. To compete, brick and mortars had to act a little more like websites. Hardware giant Home Depot saw its stock price shoot up after integrating its desktop, mobile, and physical stores, introducing options like Buy Online, Pick-up In Store. By 2016, 61 percent of retailers offered some version of the service. Curbside pickup flourished, flying in the face of the old ethos of maximizing in-store-time.

For those that adapted, a retail future exists outside of bits and bytes. The web may know your habits better than any store clerk, but that’s starting to change. IRL stores aren’t headed for the deadstock pile. They’re just going to look a bit different, get a bit smarter. Some may ditch cashiers, or cash registers altogether. Others will employ robots. And those cameras—they’re not just for catching shoplifters anymore, either.

The Future of On- (and Off-) Line Shopping

The retailpocalypse, in fact, has come full circle. In 2015, Amazon opened its first physical bookstore, then followed it up with 17 more (then raised that by a Whole Foods acquisition). The shops aren’t particularly high tech. No holograms, no VR, plenty of good old-fashioned paper. The shops occupy modest footprints, carrying only four star-and-above-rated books. Squint, however, and you can see the future: Prices are not on display, and customers must log onto Amazon’s smartphone app to see them. Prime members get lower prices, of course. “They train you when you go in the store to open your app,” says Kahn. This lets them merge your online and in-store data. More data equals better personalized marketing, tighter inventories, and lower costs.

Of course, Amazon isn’t the only one corralling your digital data to optimize your in-store experience. Personalization companies like AgilOne and Qubit have sprung up to vacuum all our clicks, tweets, and e-communiques and merge them into individual profiles that stores like Vans and Under Armour use to better target their marketing. And some are going a step further.

Earlier this year, gourmet confectioner Lolli & Pops installed facial recognition cameras in its stores’ entryways. The cameras alert clerks when VIPs (who’ve opted in) enter, then call up their profiles and generate recommendations. In the future, face-identifying cameras could track shoppers throughout stores, noting where they linger and where they don’t. Retailers could use this to maximize purchasing by, say, rejiggering floor layouts and product displays. But some businesses fail to disclose cameras, inflaming privacy defenders.

When the ACLU asked 21 of the nation’s largest retailers if they were using facial recognition, presumably for theft prevention, all but two refused to answer. (Lowe’s owned up to it.) The organization warned of “an infrastructure for tracking and control that, once constructed, will have enormous potential for abuse.” Meanwhile, other companies have convinced shoppers to knowingly trade privacy for convenience.

Register-Free Retail

Visitors to the first Amazon Go store in Seattle said it felt like shoplifting: Walk in, grab what you need, and go without ever taking out your wallet. The shop’s balletic system of computer vision, motion sensors, and deep learning renders checkout lines obsolete. Amazon reportedly plans to open another 3,000 cashier-free stores by 2021, but it has some competition.

Zippin

In April, this San Francisco concept store became the first Amazon Go challenger to open in the States. The company aims to offer its cashierless platform to hotels and gas stations.

Bingobox

This company operates more than 300 RFID-powered human-free convenience stores throughout China, with plans to reach 2,000 locations by 2019.

Kroger

The supermarket giant’s “Scan, Bag, Go,” model, already used in nearly 400 stores, lets shoppers scan their barcodes on their groceries and pay straight from their smartphones.

Standard Cognition

This San Francisco startup has partnered with Japanese drugstore supplier Paltac to open 3,000 checkout-free shops by 2020.

This year, Amazon opened its first cashierless stores in the US, followed by a handful of smaller startups. Powered by hundreds of super-smart (but not face-recognizing) cameras and an array of weight and motion sensors, stores like Amazon Go and Zippin let shoppers simply grab what they want and leave. (Once again, Amazon customers must use their app, this time to swipe in.) The surveillance offers unprecedented intel about shoppers’ habits and supposedly prevents theft. Investors see the potential. CB Insights reports that over 150 companies are developing checkout-free technology.

In this new blended, digi-physical landscape, brick and mortar stores will leverage their physical advantages, while rendering unto the web that which is better handled digitally. This might mean smaller stores that act more like showrooms than storehouses. When digital-first brand Bonobos (now Walmart-owned) opened physical “guideshops,” they functioned more like fitting rooms-cum-hangout spots. Shoppers arrived by appointment, were offered a beer, tried on clothes, then had their orders shipped directly to them from an offsite warehouse. Other stores are fashioning themselves into tricked-out lounges and event spaces. Some won’t even sell you a darn thing.

It’s called “experiential retail,” In January, Samsung opened a 21,000-square-foot Experience Store in Toronto. Visitors can test out VR headsets and tablets, chat with tech pros, or partake in autumnal smoothie classes and artist demos. The one thing they can’t do? Buy stuff. Restoration Hardware has begun fusing retail with hospitality, outfitting luxurious furniture showrooms with rooftop restaurants, barista bars, and wine vaults. In a history-is-cyclical turn, Apple’s newest DC flagship will host concerts, coding classes, workshops, and art exhibitions, recalling the multipurpose, live-band- and tea-room-appointed department stores of the early 20th century.

The ultimate fusion of convenience and experience could lie in virtual and augmented reality. As with many things VR, it’s too early to predict the impact. You can imagine it though: endless stores featuring infinite inventory, all for zero rent. Walmart filed two patents this summer for a “virtual retail showroom system.” Headset- and sensor-glove-garbed shoppers would browse digital aisles selecting products, which would be packed and shipped from an automated fulfillment center. Ikea launched an AR app last year, letting shoppers “try” out true-to-scale virtual furniture models at home before buying. And Macy’s is already rolling out VR in 69 furniture departments this year. Shoppers can design their own room on a tablet, then traipse through the space in VR.

Some retailers are going all in on the Star Trek vision of shopping. Lowe’s launched its VR Holoroom last year, leading headset-clad in-store shoppers through DIY home improvement tutorials. A month later, fashion retailer Farfetch unveiled their “Store of Future.” Touchscreen dressing room mirrors let shoppers request new sizes, holograms help them customize garments, and smart clothing racks sense when items are removed, then beam virtual versions to a smartphone wishlist.

But much of the evolution is likely to happen behind the scenes. A lot of innovation will happen in logistics, with robot-staffed fulfillment centers and delivery drones, feeding appetites for ever-faster, cheaper shipment. This year, Walmart rolled out robots in 50 stores; the wheeled automatons scan shelves and notify employees when they need to be restocked.

Stores will seek out shoppers where they spend their time, increasingly cozied up to mobile devices and smart speakers. OC&C Strategy Consultants projects voice shopping in the US will reach $ 40 billion by 2022, up from $ 2 billion this year. Given that Echos comprise nearly two-thirds of smart speakers, with Google Home racing to catch up, Amazon is once again poised to dominate. Without infinite pages of cheesecloth to browse, voice shoppers will rely heavily on recommended products (a la “Amazon Choice”). And if the smart speaker company doubles as a private label (a la “AmazonBasics”), you can guess which brand they’ll suggest first.

It all adds up to an unnervingly creepy or fantastically convenient and curated world, depending on your vantage point. Or maybe it’s all the above. On the other end of that cart you casually abandon or that data you impatiently fork over sits a business that translates that behavior into real dollars and cents. Multiply that by thousands of shoppers and you’ve got a make-or-break bottom line. Times that by millions of businesses and you’ve got a fat chunk of the economy. No wonder retailers are doing backflips to make shopping as convenient, pleasurable—and quietly invasive—as possible. It’s up to shoppers to decide where to draw the line.

Learn More

Stepping Into An Amazon Store Helps It Get Inside Your Head

Amazon’s new checkout-free stores may represent the future, but they’re just the latest in a long line of retail tech aiming to capture, digitize, and monetize your in-store behavior. One predecessor? Barcode scanners.

Welcome to Checkout-Free Retail. Don’t Mind All the Cameras

Roam the aisles of Zippin, the cashierless store of the future, where smart shelves and cameras mean perfect inventory management. (And where you never have to speak to another human.)

The Shopping Malls and Big Box Stores Gutted By E-Commerce

A haunting photo essay portrays the blanched wreckage of the retail apocalypse. Photographer Jesse Riser traveled the American southwest, stopping at more than 150 shuttered or near-shuttered shopping malls and big box stores. He transforms eyesores into meditations on the internet’s impact on public spaces.

Your Online Shopping Habit Is Fueling A Robotics Renaissance

The demand you’re creating with all your Prime orders and Birchboxes is poised to have ripple effects beyond the fulfillment center. Newer, more advanced, more collaborative robots are coming online, thanks to the packing and shipping needs generated by ecommerce. Before long, these roving, picking, super-sensing bots could move from the warehouse into our homes.

Inside Adidas’ Robot-Powered, On-Demand Sneaker Factory

The future of shopping will play out largely behind the scenes, and Adidas is striving to lead the way. The German shoemaker’s on a quest to reinvent manufacturing in the age of 3-D printing, fast fashion, and hyper-personalization, then bring it to America.

Google and Walmart’s Big Bet Against Amazon Might Just Pay Off

In its effort to retain the Nation’s Top Retailer crown, Walmart’s been pouring billions into ecommerce, including last year’s purchase of Jet.com. The company’s recent partnership with Google Home marks their foray into an arena Amazon has all but owned: voice shopping.

Turns Out the Dot-Com Bust’s Worst Flops Were Actually Fantastic Ideas

Dot-com-era failures no doubt made some ill-advised business moves, but perhaps they were also ahead of their time. Now that the internet’s more integral to our lives, remarkably similar ideas are finding second lives.

The Next Big Thing You Missed: Online Grocery Shopping Is Back, and This Time It’ll Work