#boskednan stone circle

Text

19th Feb 2023

Boskednan stone circle is a gorgeous ring up high on a ridge near Morvah. Also known as The Nine Maidens, it's another ring that's been given the folklore of young maidens dancing on a sunday - and being turned to stone by the Christian God. According to Cornovia, originally it would've included many more stones but only 11 survive to today. Urns and other remains of a human presence have been found close by, as well as the close presences of several burial sites.

megalithic.co.uk

#cornwall#kernow#stone circle#nine maidens#boskednan stone circle#neolithic#bronze age#standing stones#menhir

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Milky Way appears to the naked eye above Lanyon Quoit, one of many Neolithic sites in Britain’s newest dark sky park. Photograph By Su Bayfield

See The Heavens The Way Ancient Britons Did At This Dark Sky Park

In Cornwall—Home to Hundreds of Neolithic and Bronze Age Structures—‘Archaeoastronomy’ Tours Explore the Link Between the Moon, the Stars, and Human History.

— By Richard Collett | March 14, 2023

In Britain’s newest dark sky park, the celestial tapestry above is deeply connected to an unsually rich archaeological landscape below.

Across Cornwall’s exposed peninsula of storm-ravaged cliffs and wind-blown moors, Neolithic people built stone structures guided by the constellations as long ago as 4000 B.C. In total, about 700 Neolithic and Bronze Age structures across 115 square miles in what is now West Penwith Dark Sky Park have helped shape the landscape of Britain’s southwest. Some structures point to the heavens, others are stacked over burial chambers or built in circles around ritual zones. All sit on a bed of granite veined with copper and tin.

This long-exposure photo shows star trails above Mên-an-Tol (Cornish for “the stone with a hole”) in Cornwall. Women would climb through the hole in the 3,500-year-old granite stone during fertility festivals, such as Imbolc, which marked the start of spring and the onset of new life in the Celtic calendar. Photograph By Duncan Scobie

“This is an ancient landscape with an ancient skyscape, and we can all connect with it in some way,” says astrophysicist Carolyn Kennett, who leads “archaeoastronomy” tours, an emerging interdisciplinary field that investigates the use of astronomy in ancient civilizations.

These “low-light” tours that begin at dusk explore the intertwined nature of the moon, stars, and human history. They’re a unique way to experience this sparsely populated wild coast, with its popular summertime beaches. Walking among ancient structures, travelers connect with local heritage while gazing at the sky above.

The Rise of Astro Tourism in Cornwall

Internationally recognized dark sky areas are nothing new in the United Kingdom. There are 14 total International Dark Sky Parks and International Dark Sky Reserves designated by the International Dark-Sky Association, from parts of Cairngorms National Park in Scotland to South Downs, the newest national park in England.

While West Penwith’s distinct coastal and moorland features have long been protected as part of the wider Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), West Penwithians pushed to preserve the night sky here as well.

“It’s not just about stargazing,” says Sue James, mayor of St. Just, a town in West Penwith, who led the area’s dark sky park committee. Indeed, West Penwith doesn’t even have an observatory. “The International Dark Sky Park is as much about archaeology, wildlife, creative arts, and photography as it is about astronomy.”

In the long term, preserving the night sky helps safeguard an ancient landscape in a modern economy. Any future developments in West Penwith must now limit light pollution.

And that’s just fine with resident Judith Summers, who values the ability to step out into her garden and take a photo of Jupiter on her mobile phone. “The night sky is part of our culture here,” she says. “We don’t want to lose it.”

Land of Giants and Daring Maidens

On a late February afternoon, Kennett leads her first tour of the season in Boskednan Moor, an area with a particularly high density of ancient sites, about five miles east of St. Just in the dark sky park.

By 3:45 p.m., the sun is already dipping low on the horizon. Participants walk a rock-strewn lane sunken into the earth by centuries of footfalls by farmers and livestock. It leads to an ancient granite boundary. In the field just beyond, the Bronze Age (2500-700 B.C.) standing stone, Mên Scryfa, marks the burial place of a king, nobleman, or warrior.

This composite image blends two photographs to depict what remains of St. Helen’s Oratory, in Chapel Field below Cape Cornwall. The ruins are said to date as far back as Roman times. The chapel and the promontory of Cape Cornwall make a dazzling backdrop for the Milky Way in the southwest. Photograph By Su Bayfield

“The stone with writing,” as it’s called in Cornish, points due north to align with Carn Galva, a rocky outcropping capping a hill, or tor. It was an important focal point some 6,000 years ago, says Kennett, and even today is steeped in local mythology.

In the 19th century, William Bottrell wrote in Traditions and Hearthside Stories in West Cornwall, that Carn Galva was inhabited by a friendly giant who protected local villagers from other giants. The tors and rock formations on the moor were the remnants of battles fought between mythological titans that shaped the landscape.

Tales of behemoth beings are commonplace in Celtic cultures like Cornwall’s. Kennett believes that many of these stories are in fact derived from celestial movements over landmarks such as Carn Galva, which could have been the focus of religious ceremonies or processions.

For example, she notes that a Christian version of a local folk story says Boskednan Stone Circle, better known as the Nine Maidens, are the petrified remains of local women who dared dance on the Sabbath. However, Kennett theorizes that this stone arrangement, as well as others on Boskednan Moor, were aligned with celestial movements thousands of years before Christianity arrived in Britain.

One possible explanation is that the circle is a lunar observation site. Viewed from the circle itself, the moon passes directly over Carn Galva at the end of the Metonic cycle, when it returns to its exact starting position every 19 years.

“Lunar events happen first thing in the morning when the sun rises and the moon sets, so your shadow would be long if you were facing Carn Galva from Boskednan Stone Circle,” Kennett notes. “You would become a giant as you walked through barrows towards a tor that could be worshiped as a god, possibly.”

“But West Penwith is full of stories,” she continues. “You have to take them all with a pinch of salt.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Windswept hawthorn tree near Boskednan stone circle.

Cornwall, May 2018.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five things meme.

Tagged by @old-long-john ❤︎

Rules: Tag 15 people at the end of this challenge!

Five things you’ll find in my bag

Painkillers.

Plasters (2 types!).

Small change specifically for emergencies.

A small notebook for capturing ideas.

A spare canvas tote bag for carrying groceries.

Five things you’ll find in my bedroom

Towering piles of books.

A sock drawer ordered by colour and pattern.

Pirate bunting!

A lovely piece of art by @walter-sullivan-stubble ❤︎

The ghostly sounds of Celine Dion albums playing through the ceiling from the flat upstairs like a hideous and unwanted ‘music from another room’ meme.

Five things I’ve always wanted to do

Write a graphic novel.

Learn to roller-skate properly.

Visit the Boskednan stone circle (The Nine Maidens).

Gain encyclopedic knowledge of fern species.

Research family history.

Five things that make me feel happy

My friends.

Solving crossword puzzle clues.

Misty weather.

Strange historical facts.

Brewing the perfect cup of tea.

Five things I’m currently into

A Series Of Unfortunate Events (I am so, so late to the party).

Honey soap.

Taika Waititi (It’s all your fault @old-long-john)

Lattice pies.

Ghosts.

Five things on my to-do list

Finish my fic for the Hallowe’en challenge.

Buy new shoes which don’t let in rainwater.

Finish serious applications for writing jobs.

Find a weird museum to take my visiting friend to this weekend.

To be honest my ‘To-Do List’ is mostly “finish your PhD.”

Tagging: @angst-wizard, @gothyringwald, @walter-sullivan-stubble, @volviroyale, @questionboxjuliet, @calicocaptain @braganzas if any of you fancy it!

#Five Things Meme#In which I probably reveal really embarrassing things about my daily life#It took me a long time to think of Five Things I've Always Wanted To Do which weren't the hobbies of middle-aged British people#Brass rubbing? Birdwatching? Tower climbing?

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Petrifaction in mythology and fiction

In Cornish folklore, petrifaction stories are used to explain the origin of prehistoric megalithic monuments such as stone circles and monoliths, including The Merry Maidens stone circle, The Nine Maidens of Boskednan, the Tregeseal Dancing Stones, and The Hurlers.

0 notes

Photo

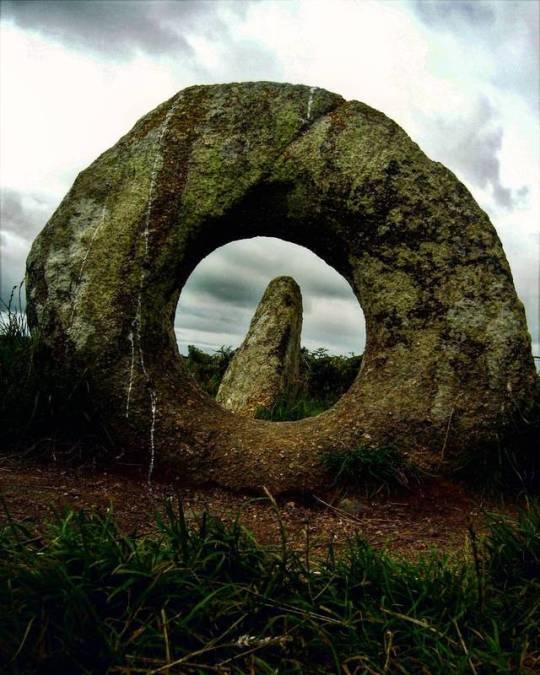

Mên-an-Tol, Madron, Cornwall. The monument consists of four stones: one fallen, two uprights, and between these a circular one, 1.3m, pierced by a hole about half its size in diameter. An old plan of Mên-an-Tol ('stone with a hole' in Cornish) shows that originally the three main stones stood in a triangle, which makes archaeo-astronomical claims for it difficult to support. They could be the remains of a Neolithic 'tomb', because holed stones are known to have have served as entrances to chambers. Its age in uncertain but it is usually assigned to the Bronze Age, between 3000-4000 years ago. Antiquarian representations of the site differ in significant details and it is possible that the elements of the site have been rearranged on several occasions. W Borlase described the monument in the 18th Century as having a triangular layout, and it has been suggested that the holed stone was moved from its earlier position to stand in a direct alignment between the two standing stones. In the mid 19th Century, a local antiquarian proposed that the site was in fact the remains of a stone circle. This idea was given additional support when a recent site survey identified a number of recumbent stones lying just beneath the modern turf which were arranged along the circumference of a circle 18 metres in diameter. The recumbent stones are somewhat irregularly spaced but the three extant upright stones have smooth inward facing surfaces and are of a similar height to other stone circles in Penwith. If this is indeed the origin of the site, the holed stone would probably have been aligned along the circumference of the circle and would have had a special ritual significance possibly by providing a lens through which to view other sites or features in the landscape, or as a window onto other worlds. There have also been suggestions that it may have been a component of a burial chamber or cist. There are instances of burial chambers close to stone circles, as at nearby Boskednan, and a barrow mound with stone cist has been identified to the north-east of the site, so it seems likely that the site was part of a more extensive ritual or ceremonial complex. (presso Mên-an-Tol)

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

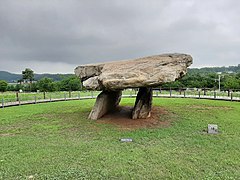

Chun Quoit, one of Cornwall’s best preserved prehistoric monuments, is spectacularly located high on a hill in West Penwith. Leaning with your back against it’s sun-warmed stones you can see for miles, expansive views across moorland, farmland and out to sea. But what was this structure for and what did it represent to the people that built it?

“Chun Cromlech, it is not so large . . . but its lonely position on the shoulder of the hill makes it an impressive object” – A.G. Folliott-Stokes, 1928.

Cornish Quoits

Cornwall’s quoits are some of our most imposing and easily recognisable monuments. There are around 20 remaining in the region, mostly clustered in Penwith. Besides Chun Quoit they include Lanyon, Mulfra, Zennor, Trethevy and Carwynnen – old Cornish names that feel suitably ancient and transportive.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

At one time there were almost certainly many more of these monuments across the region. As Ian Soulsby theorises:

“The fate of the Devil’s Coyt (a dialect spelling form) near St Columb Major, enterprisingly used as a pigsty until it collapsed in the 1840s, and then used as a source of hedging stone, reminds us that they [quoits] were probably much more numerous, like countless other types of early Cornish monuments.”

The earliest name recorded for these prehistoric structures in Cornwall is Cromlegh in an early 10th century charter for St Buryan. (Crom meaning curved, legh meaning slab in Cornish.) This word is closely related to the Welsh equivalent, ‘Cromlech‘. Where the term ‘quoit’ comes from isn’t entirely clear. Some believe the name has a connection to the game ‘Quoits’, others that it comes from a Cornish dialect word.

Caitlin Green, a historian who specialises in early literature, helped me to decipher the etymology further. Although Caitlin isn’t sure when the word was first used in Cornish, it likely comes from a Welsh word meaning ‘discus’, a solid circular object thrown for sport. Quoit “derives from the Anglo-Norman ‘coite’ borrowed into English in the 14th/15th century and implies they were seen as huge discuses thrown by giants.”

The folklore in Cornwall associated with these monuments varies from quoit to quoit but Robert Hunt reported that as a whole they were considered sacred and untouchable.

“It is a common belief amongst the peasantry over every part of Cornwall, that no human power can remove any of those stones which have been rendered sacred to them by traditional romance. Many a time have I been told that certain stones had been removed by day, but that they always returned by night to their original positions, and that the parties who had dared to tamper with those sacred stones were punished in some way.”

Resting Places

Dolmens, cromlechs, quoits, hunebedden, dolmains, anta, trikuharri – there are many names for these stone structures which can be found in one form or another all across Europe, in Central Asia and as far away as Korea. The translation of the various names ranges from ‘stone table’ to ‘bed of giants’. Almost universally however they are considered by archaeologists to be funerary structures, places where our dead ancestors were laid to rest.

Hunebedden, Netherlands. Credit: Entoen.nu

Although the design of this type of monument varies greatly from region to region but in the main they are constructed from three or more uprights supporting a large capstone. Burials or cremations were then thought to have been deposited within the void.

It was thought that these megalithic frames were once covered with an earthen mound which was subsequently eroded away by the elements, but apparently that is no longer agreed upon by archaeologists.

It seems possible that the stone structures were built to be free standing. Many dolmans, such as Chun and Mulfra, do stand on a low platform of stones however.

The chambered tombs of Cornwall are some of our oldest surviving monuments and Chun is one of the best preserved. Accurately dating quoits is difficult, however, due to the lack of finds, but they are thought to have been constructed during the middle to late Neolithic, around 3500 – 2500BC. This makes Chun Quoit 4000 – 5000 years old roughly the same age as the Pyramids at Giza.

Alternative Explanations

With ancient history there is rarely one definitive answer. In all honesty all we are ever doing is making educated guesses about what some structures were and what the people who built them intended. Throw into the mix the possibility of changes in use over the centuries that followed and it is little wonder that there are often varied and conflicting interpretations of prehistoric monuments. Quoits are no different.

“These structures, which seem to have been much more than mere burial mounds, probably fulfilled a number of ceremonial and territorial roles.” – Ian Soulsby

Although most archaeologists would agree that quoits are tombs, that they were “stone structures in which the dead were laid”, some argue that this may not have been their sole function.

Peter Herring, a landscape historian and archaeologist working for Cornwall Council, suggests that quoits could have had many different functions beyond funerary. They could have been communal gathering places, they perhaps marked very early territories or may have been the focus of ritual and spiritual practices.

John Barnett also suggests that these monuments could have been territorial markers seen from a distance and that their imposing size could be in part intended to impress visitors or those taking part in ceremonies:

“. . .the frequent burials perhaps indicate the concept of an ancestral resting place that would have been central to the symbolic expression of territory. In areas where settlement was relatively dispersed with no ‘secular’ centre, this symbolic centre could become the most important place there is and would serve a number of ceremonial functions . . . “

Stuart Dow, a prolific dowser, creator of the Earth Energies, Alignments and Leys Facebook group and a dear friend, has another slightly different take on these sites.

“They are devices to focus and harness the earth’s energies . . . every dowser has found them to be, if you like, a ‘hot spot’. The burials came later when they became forgotten as devices but remembered as something very special erected by their ancestors. Chun quoit is a great example, the radials of energy coming from [it] are phenomenal.”

Stuart Dow’s map of the energy lines at Chun Quoit

Another local fountain of knowledge Cheryl Stratton points out in her book Pagan Cornwall that there have been reports of a strange light phenomena seen dancing along the edge of Chun quoit itself. I will leave the rest to your own personal interpretation.

Beautiful Chun

“Chun cromlech . . . rises with great effect from the rock strewn moor. It stands on a little tumulus and is as prefect as when erected.” – Murray’s Handbook for Devon & Cornwall, 1859.

The name Chun is believed to be a contraction of the Cornish Chy Woon meaning ‘the house on the down’. This quoit may be one of Cornwall’s smallest but it is in a remarkable state of preservation. Writing in 1897 John Lloyd Warden Page thought it “the most perfect of the cromlechs” and it seems to have altered little since.

Chun quoit is known as a portal dolmen. It is constructed of four mighty uprights and a capstone which is roughly 3.7m (12ft) square and 0.8m (2.5ft) thick. There are two upright stones on the east and west sides, one on the north and a forth non-supporting stone on the south side completing the boxed chamber.

“The Capstone is nearly round, and as it’s top is convex and it projects considerably over the four supporting stones, which are set close together forming a square chamber, the whole structure looks at a distance like a giant mushroom” – John Lloyd Warden Page, 1897

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Chun quoit is around 4000 years old and interestingly stands close to an ancient trackway. The route is known as the Tinner’s Way and has been in use since at least the early Bronze Age but is almost certainly older. It ran between the area near St Ives to the known Neolithic axe factories on the western cliffs near Kenidjack Castle.

In 1871 when Borlase excavated Chun quoit, he describes surrounding mound and stone platform as being 9.7m in diameter and surrounded by a kerb of small upright stones. He found nothing inside the chamber of the quoit itself. Other features of interest included a possible cist identified within the mound and a line of cup marks on the surface of the capstone, possibly from the Bronze Age. Both may indicate the importance the site held for local people for generation after generation.

Surrounding Landscape

No monument exists in isolation, and Chun Quoit is no different. Close by you can find Boswens Menhir, Men-an Tol, Tregeseal Stone Circles, Lanyon Quoit, Boskednan Stone Circle and many others. But the most obvious neighbour is Chun Castle built during the Iron Age.

Entrance to Chun Castle

This impressive and complex site was built long after the quoit and deserves a post all of its own which is why I won’t cover it in detail here.

Chun Downs on which the quoit and castle stand is an atmospheric place like so much of the Penwith, a place where it is easy to imagine strange events and mystical beings at large.

“On the plain beneath Chun castle are scores of small barrows, heaps of stone, piled about the height of three feet. Some have been opened no urns or bones were found, but the earth was discoloured as if it had been subjected to fire. They lie scattered about in all directions, as if there had been some fierce battle here, and the dead had been burnt and their ashes buried on the spot where they had fallen.” John Thomas Blight, 1861.

Blight’s description suggests that Chun quoit is part of a far larger ceremonial or funerary landscape. The hill around the quoit is often deeply covered in deep undergrowth so I have personally never noticed any small cairns. But thirty years after Blight, Warden-Page also noted these features:

“The cromlech was evidently the chief tomb among many smaller ones, for the hillside is covered with the remains of tumuli.”

A Sorry Tale

In April 1939 The Cornishman newspaper reported, as a part of an article sharing ‘old timers’ memories, a strange and tragic event that had occurred eighty years before.

According to the paper in around 1859 there were two elderly sisters living in a thatched hut near Chun Quoit. The Riddigan sisters also owned some land and another cottage on the downs rented by a man named Lavers.

Lavers fell behind on his rent and in an attempt to avoid paying he perpetrated an act of cruel desperation. One night he set fire to the sister’s hut and his own cottage and fled. The two women died in the fire. According to the article a field close to the quoit was from then on known as ‘Burnt House’.

Final Thoughts

I have been visiting Chun Quoit for more than twenty years and have always assumed that it was the site of an ancient burial but what I have learnt while preparing this post has opened my eyes to so many other possibilities. Chun has taken on a different much more complex personality for me now. It just goes to show that there is always more waiting to be discovered about these wonderful prehistoric sites!

There are pages still waiting to be turned.

Further Reading:

Carn Kenidjack – the Hooting Cairn

Zennor Head

Thoughts of Carwynnen Quoit

Chun Quoit Chun Quoit, one of Cornwall's best preserved prehistoric monuments, is spectacularly located high on a hill in West Penwith.

0 notes

Text

19th Feb 2023

The sad stump of a menhir, between the Boskednan northern kerbcairn & the Boskednan Stone Circle. No records remain of why the stone has been reduced to a stump and indeed it's quite the sorry sight.

megalithic.co.uk

1 note

·

View note

Text

19th Feb 2023

Boskednan menhir & northern kerbcairn are two pretty impressive sites now hidden in the undergrowth. They're roughtly neolithic/bronze age and the menhir is set at quite the angle not far from the circle of stones making up the cairns ring. I've been able to find relatively little information on the cairn, even on megalithic.co.uk. It's still a gorgeous site rich with atmosphere.

megalithic.co.uk - Boskednan Megalith 2

megalithic.co.uk - Boskednan Northern Kerbcairn

0 notes

Photo

Boskednan stone circle, Cornwall.

May 2018.

#stone circle#standing stones#cornwall#mist#fog#landscape#photography#agavex-photography#2018#canon eos 750d

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Boskednan stone circle, Cornwall.

May 2018.

#stone circle#standing stones#cornwall#mist#fog#landscape#photography#agavex-photography#2018#canon eos 750d

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Boskednan stone circle, Cornwall.

May 2018.

#stone circle#standing stones#cornwall#mist#fog#landscape#photography#agavex-photography#2018#canon eos 750d

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monoliths, quoits, cairns and circles of stone, Cornwall is home to more megalithic sites per square mile than anywhere else in Britain. Of the 20 or so stone circles that remain today many more have been lost or destroyed.

Cornwall’s stone circles may not be as large or dramatic as those found in other parts of the country but often their beauty and isolation makes them wonderful, enigmatic monuments to visit. And they are just as mysterious as their much larger counterparts.

Discovering Boskednan

Boskednan circle, a ring similar to those of the Dawns Myin (Merry Maidens) and Boscawen Un and very interesting from its wild and commanding position. It is east-north-east of Lanyon, about 2 miles distant and plainly seen from the road and the Men an tol. The diameter is 66 feet, 8 stones stand erect, and one is nearly 8 feet in height. The eye ranges over a vast extent of uncultivated country and to the blue expanse of ocean. Directly north rise the magnificent rocks of Carn Galva. To the south is the mine of Ding Dong, to the east is seen Mulfra Quoit on the crown of a barren height some 2 miles away.

Murray, 1859

Boskednan stone circle is one of Cornwall’s lesser well known circles. It stands on isolated moorland on West Penwith. Walkers can find the stone circle on a lonely ridge not far from the Men Scryfa stone and Men an tol. At the foot of this hill you will also find the Venton Bebilbell well. The stones of this circle are an average of 1.2m (4ft) high, with the tallest stone reaching 2m.

Borlase excavated at the site in 1872. He uncovered a cist burial just outside the circle. The burial contained an urn and shards of pottery. The urn had small handles and a twisted cord decoration, according to Albury Burl in her book The Stone Circles of the British Isles. This pottery was of a type known as Cornish Trevisker Ware dating from the early Bronze Age.

Reconstruction of Trevisker Ware by English Heritage

Boskednan stone circle like several other stone circles in Cornwall is also known as The Nine Maidens. But this stone circle does not have nine stones, it never has done. In fact, there are thought to have been nineteen here (only eleven now standing).

Nineteen Stones

In Cornwall, especially in Penwith, nineteen seems to be a significant number. The Merry Maidens, Boscawen-un and Tregeseal all have nineteen stones.

It is thought that the number 19 is in someway connected to astronomy. Specifically to the Metonic Cycle. This is a period very close to 19 years (235 lunar months) after which the new and full moons return to the same dates of the year. Basically the lunar and solar cycles coincide every 19 years. It seems possible that our ancestors used these circles to mark the passage of time, amongst other things. One stone for each of the years before the ‘clock’ reset.

What is safe to say is that each precious monument that remains gives us a small window into the world that our ancestors lived in. These structures are our oldest connections to the past and their first messages to us. It is down to us to decipher them.

Further Reading:

Cornwall’s Prehistoric Holed Stones

Goodaver Stone Circle – Bodmin Moor

The Stone circles of The Gambia, West Africa

Walking Opportunities:

Rosemergy to Ding Dong Mine Circular Walk

Boskednan Stone Circle Monoliths, quoits, cairns and circles of stone, Cornwall is home to more megalithic sites per square mile than anywhere else in Britain.

0 notes