#brother was born in 1920 its a product of the time

Text

I'm grateful every day

#doctor who#classic who#classic doctor who#the doctor#doctor who classic#talkies#blackface#blackface mention#i learned this and suddenly the grass is greener and the world is beautiful#suddenly peace and love is real#and i appreciate every classic who doctor a little bit more#if it were up to Patrick the first black doctor would also have been the second... unfortunately#he's a little confused but he's got the spirit#also please don't taint his memory with this#brother was born in 1920 its a product of the time

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panasonic Service Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad 7337443480

Panasonic Service Center Near Kukatpally Hyderabad - solutions for Split AC /Window AC, Repair, Installation and Uninstallation | Removal, Panasonic Washing Machine Fully Automatic Service Center Near Kukatpally / Front Load / Top Load Single door / double door / Side by side-Gas filling / No cooling, Not working near Miyapur, Nizampet, Pragathinagar, Kondapur, Madhapur. Call our eServe Panasonic customer support Kukatpally / Panasonic customer care Kukatpally / Panasonic service center number Kukatpally 7337443380 for best in class services.

Japanese company Panasonic Ac Repair Center Near Kukatpally Hyderabad embarked on creating elements and expanded to manufacturing entire appliances. the corporate survived warfare II, at the same time benefitting from a postwar abundance amount and troubled to navigate the political aftermath. It conjointly weather-beaten varied economic crises. Panasonic Service Center Near Kukatpally Hyderabad has pivoted often, expanded globally and these days continues to appear toward the long run of technology, together with teaming up with Tesla.

Here could be a temporary history of the company’s initial century:

Panasonic Repair Center Near Kukatpally Hyderabad was based on March seven, 1918, by Konosuke Matsushita, who was 23 years recent at the time. Previously, he’d been living in a very two-room apartment house together with his woman, Panasonic Service Center Near Kukatpally Hyderabad Mumeno Iue, and her teen brother, Toshio. when operating as an apprentice to hibachi and bicycle manufacturers and dealing for the port light bulb Company, Matsushita had returned up with a style for a replacement quite light-weight socket.

Despite discouragement from his supervisor, Panasonic Service Center Near Kukatpally Hyderabad Matsushita and his family tried to sell the devices out of their homes. They even sold off a number of their most precious possessions to form ends meet. Meanwhile, Matsushita distributed his product offerings, eventually fulfilling an order for blower insulation plates.

This Panasonic Service Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad gave the trio the means that to maneuver into a much bigger house and Matsushita electrical Housewares producing Works was born. Matsushita quickly expanded the company’s line of business to incorporate an attachment plug and a two-way socket. The previous recycled the metal screws from used light-weight bulbs. Panasonic Service Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad By the top of 1918, the corporate had big to 20 workers.

Matsushita was before his time in a way as his management approach. Once the corporate was a pair of years recent and had 28 workers, he fashioned what he referred to as the “Hoichi Kai,” which interprets to “one-step society.” Panasonic Service Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad It brought workers along to play sports and participate in alternative recreational activities.

Another unconventional leadership maneuver Matsushita spearheaded was transparency within the early 1920s, employee retention was a serious drawback in Japan Panasonic Repair Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad , initial because of competition among corporations, Panasonic Service Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad then attributable to economic worsening. Matsushita’s philosophy was one in all trust, and he set to share trade secrets even with new workers to create trust in the least levels of the organization. By the top of 1922, Panasonic Ac Repair Center Near Me the corporate had 50 workers and a replacement plant.

Related: 2018 could be a Milestone Year for powerful corporations together with Google, Tesla, and Airbnb

Since its foundation in 1918, it's big to become one in all the biggest Japanese physics producers together with Sony and Toshiba, additionally to electronics, Panasonic Service Center Near Kukatpally Hyderabad offers non-electronic merchandise and services like home renovation services. Panasonic Service Center Near KPHB was hierarchical the 89th-largest company within the world in 2009 by the Forbes international 2000 and is among the Worldwide high 20 Semiconductor Sales Leaders, Panasonic Repair Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad manufacture and market the electrical lamp sockets and plugs he designed. It had been incorporated in 1935 and started increasing chop-chop into a variety of various electrical product lines, throughout the thirties, it superimposed such electrical devices as irons, radios, Panasonic Ac Repair Center Near Me phonographs, and light-weight bulbs. Within the 1950s it began manufacturing semiconductor device radios, TV sets, tape recorders, stereo instrumentality, Panasonic Repair Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad and enormous home appliances, throughout the successive decade, it superimposed microwave ovens, air conditioners, and videotape recorders. Most of its merchandise square measure marketed beneath the complete names Panasonic, Quasar, Panasonic Repair Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad National, Technics, Victor, and JVC.

Non-consumer merchandise embodies minicomputers, phone instrumentality, electrical motors, chemical, and star batteries, and cathode-ray tubes the corporate conjointly has developed and marketed electronic measure and temporal arrangement instruments, copy machines, Panasonic Repair Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad automatic control devices, workplace automation instrumentality, and merchandise within the communications, broadcasting, and solar power fields. the corporate is noted for its significant investment in analysis and development; additionally, Panasonic Repair Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad to its main analysis laboratories, every Panasonic producing division is backed by its analysis team.

#Panasonic Repair Centre Near Kukatpally Hyderabad#Panasonic Repair Centre Near Kukatpally#Panasonic Repair Near Kukatpally#Panasonic Service Near Kukatpally Hyderabad#Panasonic Service Centre Near Kukatpally Phone Number

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nezha Reborn annotations - Part 1

Since New Gods: Yang Jian is about to enter NA theaters this week, and before I do a huge information dump about that movie, I wanted to write about its prequel - Nezha Reborn.

I've already seen Yang Jian twice in cinemas here in Australia, and the animation has markedly improved in the one year since Nezha came out - it's definitely worth seeing on the big screen. You don’t need to watch Nezha before Yang Jian but if you’re interested in the lore, then you should lol. It's on netflix.

My original thread on twitter.

Background

Nezha is one of the most well-known characters from the 16th Century Chinese Novel Investiture of the Gods (IOTG), with countless adaptations based on his legend.

New Gods: Nezha Reborn is one of the latest portrayals of the character, and is the first move in Light Chaser Animation Studios' attempt at establishing a New Gods cinematic universe.

Nezha’s origin story

Nezha was born as a round ball of flesh after his mother Lady Yin was pregnant for three years. His dad Li Jing thought he was demon spawn, so tried to kill him but was spared by the immortal Taiyi Zhenren who became his master. At seven years old, he caused a lot of trouble like accidentally killing a demon from 1000 miles away and killing the dragon king Ao Guang’s third son Ao Bing as well as his right hand man the Yaksa Li Gen. When Ao Guang demanded retribution from Li Jing, Nezha chose to sacrifice himself instead. His master later resurrected him using lotus roots to construct a human body, and he came back more powerful than ever. 3000 years later...

Breakdown

Donghai (East Sea). It was the mythical underwater city that Nezha once conquered, now depleted of all its water resources. Set design is inspired by Republican-era Shanghai and Manhattan in the 1920s and 1930s. The poor Chinese style backdrop is contrasted against the glitz of the Western style architecture in the rich area. Rickshaws were commonplace on the streets.

Fashion is also blend of east and west, like the guy wearing kung fu shoes with a denim jacket.

The qipao was a favored dress among women at the time, popularized by Chinese socialites and high society women in Shanghai. Flapper fashion also influenced Kasha’s outfit, blending eastern and western styles.

Li Yunxiang shares the same surname as the original Nezha. His brother Jinxiang’s name is also similar to Nezha’s eldest brother Jinzha. Jinxiang’s look is very typical of the republican era - complete with his center-parted hair and round glasses.

Old Li has the same temperament as Nezha’s dad, The Pagoda Bearing Heavenly King Li Jing.

Who is Yunxiang’s adoptive sister Kasha? She’s an orphan of Belarusian descent, however not much else is known about her past. Her name means porridge in Belarusian. It might be a corruption of Katyusha (喀秋莎) with middle character removed in order to follow Chinese naming conventions idk.

If you know the history of the Republic of China, there were many girls like Kasha in that era. Her father was a soldier and left Kasha and her mother after the war.

✨Princess✨ Ao Bing~~ and the Yaksa Li Gen. Ao Bing is the third son of the Dragon King of the East Sea. The Yaksa Li Gen is the dragon king’s right hand man.

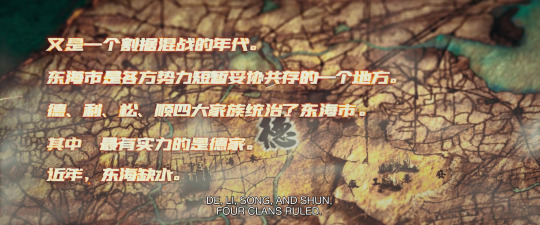

The four big clans - De, Li, Shun, Song (德家、利家、顺家、松家) - actually corresponds to the titles of dragon kings of the four seas. King De, Dragon King of the East Sea; King Li, Dragon King of the South Sea; King Shun, Dragon King of the West Sea, King Song, Dragon King of the North Sea.

A netizen looked this up and really wanted to kneel to Light Chaser for their worldbuilding.

Fun fact: the white horse from Journey to the West is the third son from the Song family.

H*rley-D*vidson Darrley-Hudson product displacement on the arm of Kasha’s jacket:

Actually the film has left some hints about her past. There are some Soviet-style badges pinned to her jacket, along with some small badges that Kasha herself added as well. Since this jacket is huge, it can be assumed that it was left to Kasha by her biological father.

The giant buddha statue is reminiscent of the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang, Henan.

Daddy! Ao Guang, the dragon king of the East Sea.

Art deco details on the hood ornament, decals and invitation card.

Monkey’s suit is basically a hot pink version of the Zhongshan suit, a style of menswear introduced by Sun Yat-sen during the republican era, adapted from Japanese student wear. The four pockets are said to represent the Four Virtues of propriety, justice, honesty, and shame. He's blinged up his prayer beads too.

Does this mean Dr. Su is a descendent of Su Daji, the femme fatale of IOTG? Or could she actually be Daji’s reincarnation? Now I don’t know whether to trust her or not.

All these sea creature demons. Why? Chinese dragons are aquatic. They live underwater, and command water-based attacks, unlike western dragons who breathe fire. So it makes sense for them to control an army of demons that came from the deep.

So this is the crystal palace.

After Nezha’s death, Li Jing found out that Nezha’s mother had built a temple in his honor and burned it down because he was still angry at his son for all the trouble he caused to the family. The soul of Nezha was pissed and after his reincarnation, began to pursue his dad with the intent to kill. It took several parties to step in before matters were resolved.

Looks like monkey likes to listen to Peking Opera.

The Pukui fan, commonly known as the cattail fan, is a fan made from palm leaves and stalks. Lightweight and cheap, it is the most widely used fan in China.

Part 2|Part 3

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

1932 Graham Blue Streak

By the standard of 1932, the Graham Blue Streak was genuinely shocking. As soon as the wraps came off, it commanded the automotive world’s attention just like the Cord L-29 and the Ruxton had a few years earlier. But even in the heady atmosphere of 1929, the L-29 was exotica, the Graham was a mainstream family car. Since so many of its best bits were quickly copied, some of its impact is lost today, but it was the kind of aesthetic design that shifted the industry big time.

The Blue Streak is known for one thing above all —the introduction of fully enclosed (or “Valanced”) fenders—but there was much more to it than that. The whole design subtly evolved the shape of the automotive form, and while the fenders were a first on a mainstream production car, some of the other changes were due to innovation you couldn’t see, like the car’s new, and very different, frame design. It was also as good to drive as it was to look at.

The Indiana-born Graham Brothers, Joseph (born 1882), Robert (1885), and Ray (1887), were still relative newcomers to passenger cars when the Blue Streak was unveiled in December of 1931, but they were anything but novices. After getting their start in the glassmaking business (which later provided lots of residual income), they began producing truck conversion kits for Model T Fords in 1919, then started building their own trucks, then building trucks for Dodge, and ultimately selling their firm to (pre-Chrysler Corporation) Dodge.

They got big payouts, but departed Dodge in April of 1926, with a stipulation that they couldn’t make any trucks under their own name for five years. Without the Grahams, the financial firm that by then owned Dodge, Dillon-Read, floundered, which is why the company ultimately got bought by Chrysler, but the Grahams had moved on.

The following summer, they bought the Paige-Detroit concern of Dearborn, Michigan (maker of Paige and Jewett cars) in 1927 and morphed its products into their first car line (styled by LeBaron), announcing a new line of Grahams (and some warmed-over Paiges) for the 1928 model year. They were instantly successful, with 73,000 cars sold the first year and 77,000 in 1929, but then the depression came and sales crashed, to just over 20,000 in 1931. The Blue Streak was purposefully created to turn the tide.

While the Grahams were truck guys, they knew that style sold cars, particularly after the success of Harley Earl’s 1927 LaSalle and the high-profile changes it created at GM. Even a firm doing as well as Graham among smaller independent makes did not have the resources to hire an “Art & Colour” section the way GM (and soon, Chrysler) did, so instead they went in two directions. First, they had their engineers run wild with new ideas, and second, they turned to body supplier Murray and their ace designer Amos Northup, for style.

Northup began his career as a furniture and drapery designer in his native Ohio but later went to work for Pierce-Arrow in Buffalo, New York, first designing trucks, then car interiors, then exteriors and advertising design for the company. He parlayed that experience into designing the Wills St. Claire car but soon grew frustrated by C.H. Wills’ conservative style choices. He went to Murray in 1926 or early 1927, but he was frustrated there too.

In the 1920s, designers got no respect. It was engineers who commanded how cars were made. This was probably doubly true for Northup, who was short, unassuming, and nothing like the flamboyant Ray Dietrich (Murray’s lead designer when Northup joined) or Harley Earl.

He was underpaid too, and quit in 1928, and in his time away from Murray he designed the 1930 Hudson, the Willys “Plaidside” Roadster, and the company’s compact 1930 Whippet line. Murray hired him back, with a big raise, in 1929. His next major project was the 1931 REO Royale, a curvaceous design that today looks more like a car of 1932-33 thanks to Northup’s round shapes and streamlining. The Blue Streak was a natural next step.

The Blue Streak would not be radical in the same sense as the L-29. Its mechanical pieces were conventional and it used the typical two- and three-box shapes of the day, but all the details telegraphed the future.

Northup’s “Unified Design” idea was that the entire car should look harmonious as if it were one solid piece. The enclosed fenders were only part of that. Many of the trim pieces, and particularly the low-set headlights, were painted rather than chromed, and the body sat very low, with the curious absence of any real trace of the frame. The undercarriage was entirely hidden even at the rear. The windshield, grille, and hood vents were all angled identically. Optional disc wheels made them look even sleeker.

The lowness, of course, was down to the engineers. Northup’s visuals get the glory, but that frame was what enabled them. Chief engineer Louis Thorns devised new side rails with no forward kick-up, as was normal then, and a “banjo” arrangement through which the rear axle passed, rather than having the frame curve above the axle as was normal. The springs were mounted outboard, rather than under the frame, which necessitated a slightly wider-than-normal track.

This made the Blue Streak a very good handler for its time, but it was also a double-edged sword. The much more rigid frame and huge decrease in body roll relative to other cars, aided by gigantic rubber bushings in the rear, meant much higher cornering limits than drivers were used to. This led to a reputation for snap oversteer among Graham salespeople, but the car was quick, with a 90-horsepower, 245.4-cid (4.0L) alloy-head straight eight and a fully-synchronized three-speed gearbox.

In the depths of the depression, many makes were trying to sell cars on durability and value, and while Graham had those attributes, the styling was the star of the show. Still, sales slid to just under 13,000 cars.

It did, however, send competitors scrambling. Virtually all of Graham’s competitors retooled at least their fenders for 1933 to match, forever hiding away the road dirt that would coat the inner areas of the fenders and taking the first step towards fully enclosed bodies, a streamlining process that would complete itself only after WW2. While everyone else tried to catch up, the ‘Streak got few changes for 1933. In 1934, they bolted on Superchargers.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Nail Coloring Tools: From Classic to Cutting-Edge

Nail coloring has been an integral part of self-expression and beauty rituals for centuries. From ancient civilizations using plant-based dyes to modern-day nail salons offering a plethora of vibrant colors, nail art has evolved significantly. One critical aspect of achieving the perfect nail look is the use of appropriate nail coloring tools. In this blog, we'll take a journey through the history of nail coloring tools and explore the wide array of options available today.

Ancient Origins: Natural Pigments and Henna

The practice of adorning nails with color dates back to ancient times. Egyptian and Chinese civilizations used natural pigments derived from plants and minerals to create stunning nail art. The earliest forms of nail coloring tools were rudimentary brushes made from animal hair or reeds. Additionally, henna, a plant-based dye, was widely used in India and the Middle East for intricate nail designs that symbolized status and beauty.

Enter Modernity: The Birth of Nail Polish

It wasn't until the early 20th century that modern nail polish was born. In the 1920s, Charles Revson, along with his brother and a chemist friend, developed the first colored nail lacquer. This led to the formation of Revlon, a renowned cosmetics company that revolutionized nail coloring for generations to come. The introduction of nail polish as a mass-market product significantly expanded the range of colors available and simplified the nail coloring process.

Nail Coloring Tools: The Essentials

The tools used for nail coloring have evolved and become more sophisticated over time. Some of the essential tools for a perfect manicure include:

Nail Files: Used to shape and smoothen the nails before applying polish.

Cuticle Pushers: To gently push back the cuticles for a clean canvas.

Base Coat: Creates a smooth surface and protects the nails from staining.

Nail Polish: A vast selection of colors and finishes, from matte to glittery, to cater to every taste.

Nail Brushes: These come in various shapes and sizes, perfect for intricate designs or simple strokes.

Nail Airbrushes: This tool can spread nail polish over a large area, as well as blend colors, stain nails, etc.

Nail Dotting Tools: Used for creating dots, patterns, and precise designs.

Nail Stamping Plates: Allow for transferring intricate designs onto the nails quickly.

Top Coat: Applied as a final layer to seal the polish and add shine, increasing longevity.

Nail Art Revolution: Stickers, Decals, and Beyond

The nail art revolution of the late 20th and early 21st centuries brought forth an explosion of creativity. Nail artists and enthusiasts experimented with stickers, decals, and 3D embellishments. The market responded by introducing press-on nails, nail wraps, and adhesive designs, catering to those seeking quick and convenient options for nail art.

Tech Meets Beauty: Digital Nail Printers

As technology continues to shape our lives, it has also made its way into the beauty industry, including nail coloring. Digital nail printers have gained popularity in some salons, allowing customers to print intricate designs directly onto their nails. These printers use specialized software and UV-curable ink to create stunning patterns and images in a matter of seconds.

Conclusion

The evolution of nail coloring tools has come a long way from the humble reed brushes of ancient civilizations to the sophisticated digital nail printers of today. Nail art and self-expression have become inseparable, allowing individuals to showcase their creativity and personality through their manicures. Whether you prefer the classic elegance of a single-colored polish or the intricate designs of modern nail art, the abundance of nail coloring tools ensures that everyone can find the perfect method to create their unique nail masterpiece. So, let your imagination run wild and embrace the world of nail coloring possibilities!

0 notes

Text

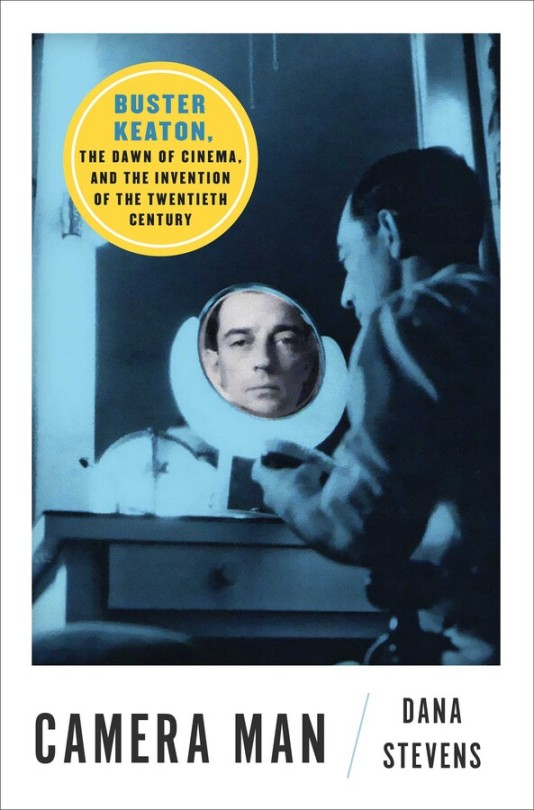

Salon film critic Dana Stevens’s first book is not so much a conventional biography of a silent screen comedy legend (for that you will have to turn to James Curtis’s forthcoming Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life) as it is a fascinating and appreciative cultural study of Buster Keaton’s (1895–1966) life in the context of his time. To understand Keaton, argues Stevens, is to understand the history of cinema. “Keaton’s birth and death were separated by a stretch of just seventy years, but in those years the country and the world had been profoundly reshaped by a technology born the same year he was: film."

On December 28, 1895 when French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière first screened their moving pictures shot on their patented Cinématographe machine to a paying public, young Joseph Frank Keaton (soon to be nicknamed Buster) was two months old, the first child of vaudevillian parents who would incorporate him into their traveling act. At that Paris screening, the world’s first film comedy debuted as a 49-second sketch involving a young boy pulling a prank on an older man with a garden hose. Stevens persuasively connects that cinematic precedent with the slapstick father-son conflict that made the Three Keatons’ act one of the most popular on the early 20th century vaudeville circuit, even if some of their most outrageous stunts barely skirted emerging child labor laws.

It was a theme that Keaton would continue to explore as vaudeville gave way to an emerging entertainment form, the movies. A chance meeting with Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle’s stage manager on a New York street in 1917 led to the most creative decade of Keaton’s life, an exhilarating period when pioneering filmmakers were experimenting with what the new technology could do. In analyzing Keaton’s cinematic output during those years, from the classic two-reeler One Week (1920) to his Civil War epic The General (1926), Stevens writes admiringly: “The breadth of his output…was the result of being a consummate craftsperson and a singularly gifted entertainer at a time when the new medium was its most malleable. His curiosity and ambition grew to fit what movies were becoming, and the form, in turn, expanded to make space for what he could do.”

With the arrival of talking pictures looming just over the horizon, Keaton’s independence as a filmmaker ended in 1927 when his production company was shut down and he signed a “fateful contract” with MGM. “The trajectory his career had followed from early childhood to early middle age, that smooth and steady upward arc, had hit its peak and was about to hit a steep, perilous drop.” What followed were miserable years at a studio that did not know what to do with Keaton’s talent, two failed marriages, a humiliating firing by Louis B. Mayer in 1933, and bouts with severe alcoholism.

Yet unlike other biographies that depict the latter half of Keaton’s life as a Shakespearean tragedy, Steven’s book portrays the “Great Stone Face” as a stoic man who got on with his life despite its difficulties, finding happiness in a third marriage, exploring the possibilities of early television, mentoring rising stars like Lucille Ball, getting small roles in movies running the gamut from Limelight (1952) to A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), and being rediscovered by a new generation of film lovers.

Clearly preferring the “white rose of Keaton” to the “red rose of Chaplin,” Stevens writes with verve and deep affection for her subject. But her study is not hagiography; in examining the influence of Bahamian-born entertainer Bert Williams (1874–1922) on Keaton’s work, the author is clear-eyed about Keaton’s race-based humor in his films. “Buster Keaton was ahead of his time in many ways, but when it came to the ambient cultural racism of the Jim Crow era, he was unfortunately very much a product of it.”

Integrating wide-ranging cultural research into a cohesive, entertaining whole, Camera Man is a fabulous read and will inspire die-hard fans and newbies to watch Keaton's silent films (now being beautifully restored by Cohen Media Group and Italy's Cinecita di Bologna) to enjoy their magic with fresh appreciation.

For readers on the East Coast, the author will be making several appearances along with screenings of some of Keaton’s films: https://www.simonandschuster.com/p/ca.... (less)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOT FORGOTTEN!! Born on this day on March 4, 1913 - known as John Garfield professionally and Julie to his family and friends. Here are some photos and info about his early days as an actor.

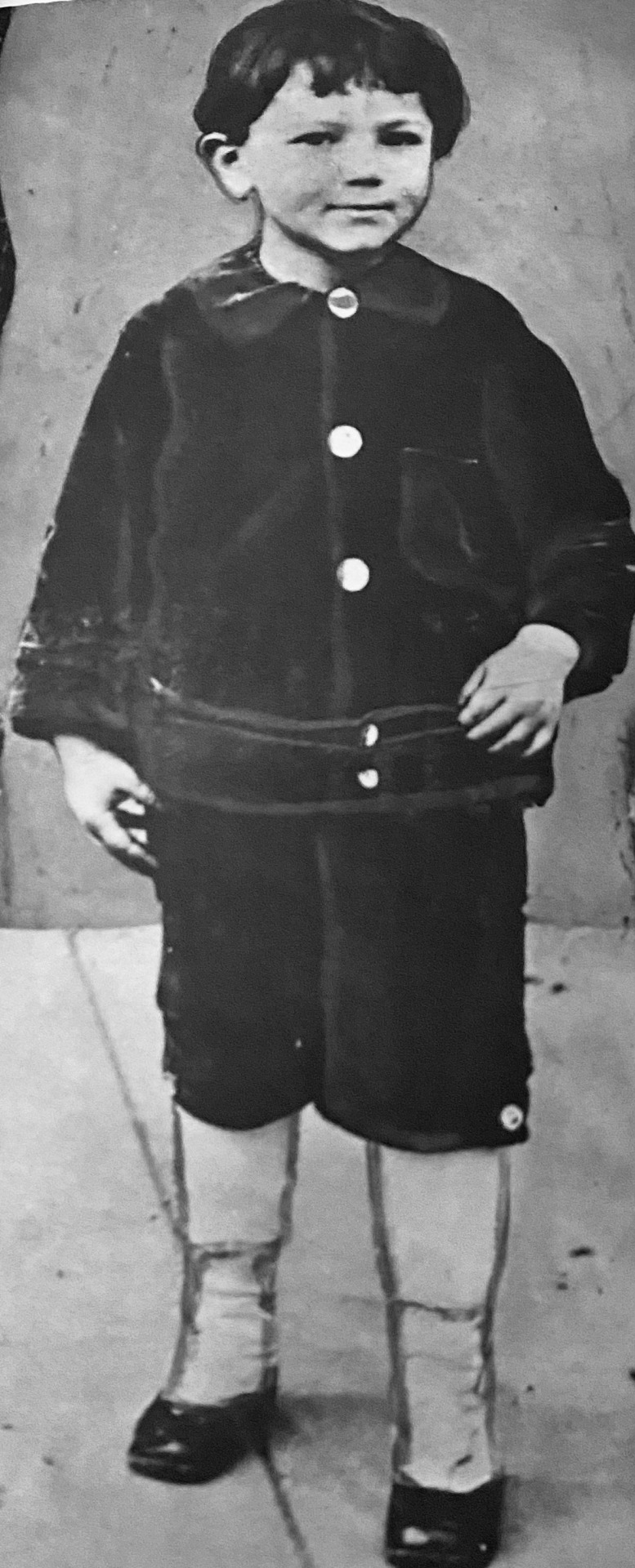

Jacob Julius Garfinkle was born in NYC’s Lower East Side on March 4, 1913. His mother, Hannah (Margolis) was of Ukrainian descent and his father, David of Russian Crimean origins.

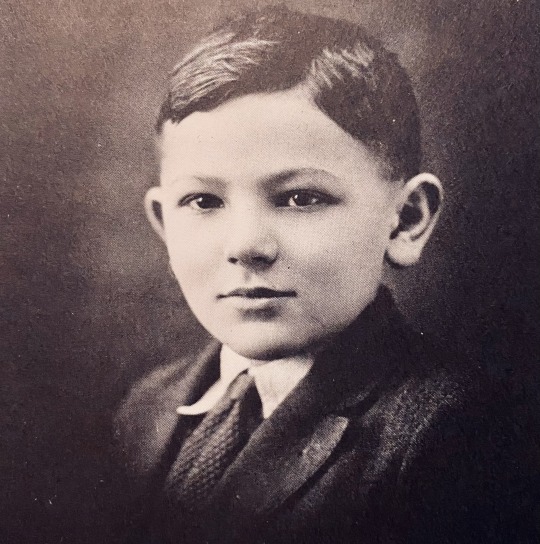

Not sure how old he is here is this photo—the face is Julie’s but the body looks oddly painted in. Julie lost his mother Hannah at the tender age of seven in 1920.

Julie and his brother, Max born in 1918 stayed with other relatives in tough neighborhoods after Hannah died.

In the photo above, Julie is age 13, just before his new stepmother, Dinah was able to enroll him at P. S. 45 in the East Bronx. The principal was innovative educator, Angelo Patri. Arts education was advocated, and Patri championed young Julie’s dramatic abilities in this crucial developmental time.

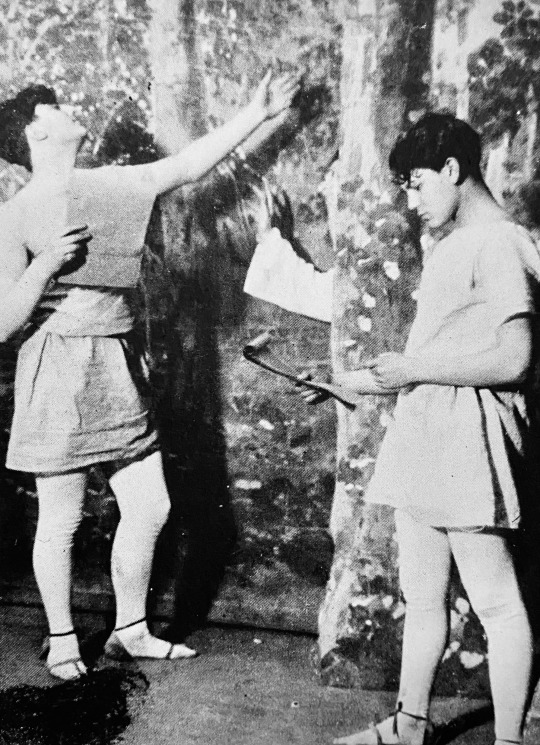

Julie is on the right in Roosevelt High School’s production of A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM. Soon after, he applied to THE AMERICAN LABORATORY THEATER (The Lab) run by Richard Boleslavski and Maria Ouspenskaya. These two players from the Moscow Art Theatre are credited with first teaching what evolved into THE METHOD in the U. S.

Konstantin Stanislavski, cofounder of the Moscow Art Theatre, also an actor and director, developed the SYSTEM of acting. It was embraced and by The Group Theatre and very widely associated later with The Actors Studio.

Check out the book from Isaac Butler, THE METHOD, How the 20th Century Learned to Act.

Julie is shown above in the role that gave him his big break—COUNSELLOR-AT-LAW. The new Equity cardholder now uses the stage name: Jules Garfield. The lead was played by Paul Muni opening in Chicago before its New York run. Tennis anyone?

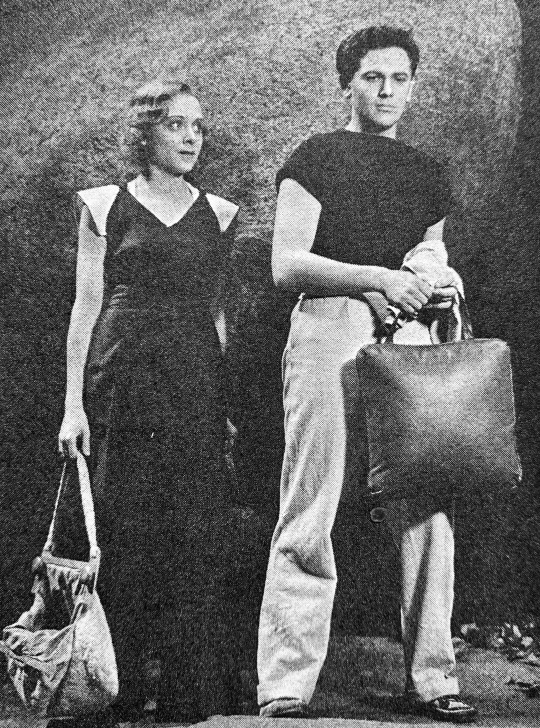

Julie playing Chick Kessler is shown above with Katherine Locke in HAVING WONDERFUL TIME.

Julie aspired to become a member of The Group, an ensemble of actors. He was rewarded with acceptance and is shown above in the production of AWAKE AND SING with Phoebe Brand.

Before Hollywood came calling and John Garfield started his film career, he made a name for himself in his Broadway appearances. Above is an early publicity photo of the handsome young stage actor housed in the digital collection of The New York Public Library.

#john garfield#happy birthday John garfield#the Method#the American laboratory theater#Moscow art theatre#the group theatre#the actors studio#Angelo Patri#having wonderful time#awake and sing#counsellor-at-law#Paul Muni#Maria ouspensaya#Richard boleslavsky#Julius Jacob Garfinkle#Jules Garfield#Isaac butler the method#Konstantin Stanislavski#Stanislavski system

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2016 My life was Not really much .. I was born in 1956 …which makes me well,,, old! I am an old Sea Hag ! I fucked up somewhere along the line I never married .. nor did I have any children ., that lived !

Actually I am a product of my Parents ! Or should I get right down to the crust ,.,. my grandparents ! My Dads Mother Rosemary Clayton born in 1899 July 14 Married Harry Elliott after WW1. My father Harry Clayton Elliott was born November 14, 1920.. it was Rumored that His Mother Rosemary ran screaming from the house after giving birth !? Her new Borns eyes needed salversand ? Rosemarys husband seemed to have gottenSyphilis and given it to his wife., So technically my dad is Rosemarys Baby! Which makes me …One of Rosemarys Babys ,..Babies . I am pretty sure there were trust issues along with the insanity that shows up after the Syphilis has taken its toll on your brain etc … grandfather died in an insane asylum.. My Mothers parents had to get married .. they went out on New Years Eve… My Mother Irma Louisa Gilmore was Born September 29 1924, to Arnold Gilmore & Catherine Cullen . Her heritage Irish Catholic , His German Scotsman a Baptist . They were from very different worlds . His Mother Sarepta looked down her nose at her daughter-in-law , was convinced she got pregnant on purpose to trap her son, on their first date. They were both employed at Foremost Dairy . What I do know is her parents had sex at least one more time because I have an uncle Arnold Eugene Gilmore born on January 1 1930., My mom said that she and her mom shared a bedroom and her dad and brother shared a bedroom! There wasn’t any affection hugs and kisses while growing up ! My mother was a wild one ! She once got married to an guy in the air force cause there was nothing else to do that Saturday Night! (She was 17 years old) My fathers childhood was the exact opposite,,, my father was enrolled in Catholic School varsity basketball team , His Mother ran a Boarding House his father had been employed by the RailRoad however was in an institution .one of the boarders was The chief of police Toby Rikley he and Rosemary were an item, however she was carrying on with Johnny Slayzack the Bartender at the Club downtown. One evening after dinner Toby asked my father to come into his room he handed my father an envelope told him to give it to the nuns at his School in the morning . My father said alright . Later that night he was awaken by the sound of a gunshot. Toby had committed suicide one shot to his head! It seems he came home early that day and found Rosemary in bed with Jonny the bartender! In the envelope Toby had given my father …. The tuition for the next three years at Catholic School ..

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mysterious Death of a Hollywood Director

This is the tale of a very famous Hollywood mogul and a not-so-famous movie director. In May of 1933 they embarked together on a hunting trip to Canada, but only one of them came back alive. It’s an unusual tale with an uncertain ending, and to the best of my knowledge it’s never been told before.

I. The Mogul

When we consider the factors that enabled the Hollywood studio system to work as well as it did during its peak years, circa 1920 to 1950, we begin with the moguls, those larger-than-life studio chieftains who were the true stars on their respective lots. They were tough, shrewd, vital, and hard working men. Most were Jewish, first- or second-generation immigrants from Europe or Russia; physically on the small side but nonetheless formidable and – no small thing – adaptable. Despite constant evolution in popular culture, technology, and political and economic conditions in their industry and the outside world, most of the moguls who made their way to the top during the silent era held onto their power and wielded it for decades. Their names are still familiar: Zukor, Goldwyn, Mayer, Jack Warner and his brothers, and a few more. And of course, Darryl F. Zanuck. In many ways Zanuck personified the common image of the Hollywood mogul. He was an energetic, cigar-chewing, polo mallet-swinging bantam of a man, largely self-educated, with a keen aptitude for screen storytelling and a well-honed sense of what the public wanted to see. Like Charlie Chaplin he was widely assumed to be Jewish, and also like Chaplin he was not, but in every other respect Zanuck was the very embodiment of the dynamic, supremely confident Hollywood showman.

In the mid-1920s he got a job as a screenwriter at Warner Brothers, at a time when that studio was still something of a podunk operation. The young man succeeded on a grand scale, and was head of production before he was 30 years old. Ironically, the classic Warners house style, i.e. clipped, topical, and earthy, often dark and sometimes grimly funny, as in such iconic films as The Public Enemy, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, and 42nd Street, was established not by Jack, Harry, Sam, or Albert Warner, but by Darryl Zanuck, who was the driving force behind those hits and many others from the crucial early talkie period. He played a key role in launching the gangster cycle and a new wave of sassy show biz musicals. At some point during 1932-33, however, Zanuck realized he would never rise above his status as Jack Warner’s right-hand man and run the studio, no matter how successful his projects proved to be, because of two insurmountable obstacles: 1) his name was not Warner, and 2) he was a Gentile. Therefore, in order to achieve complete autonomy, Zanuck concluded that he would have to start his own company.

In mid-April of 1933 he picked a public fight with Jack Warner over a staff salary issue, then abruptly resigned. Next, he turned his attention to setting up a company in partnership with veteran producer Joseph Schenck, who was able to raise sufficient funds to launch the new concern. And then, Zanuck invited several associates from Warner Brothers to accompany him on an extended hunting trip in Canada.

Going into the wilderness and killing wild game, a pastime many Americans still regard as a routine, unremarkable form of recreation, is also of course a conspicuous show of machismo. But in this realm, as with his legendary libido, Zanuck was in a class by himself. He had been an enthusiastic hunter most of his life, dating back to his boyhood in Nebraska. Once he became a big wheel at Warners in the late ’20s he took to organizing high-style duck-hunting expeditions: the young executive and his fellow sportsmen would travel to the appointed location in private railroad cars, staffed by uniformed servants. Heavy drinking on these occasions was not uncommon. (Inevitably, film buffs will recall The Ale & Quail Club from Preston Sturges’ classic comedy The Palm Beach Story, but DFZ and his pals were not cute old character actors, and their bullets were quite real.) Members of Zanuck’s studio entourage were given to understand that participation in these outings was de rigueur if they valued their positions, and expected desirable assignments in the future. Director Michael Curtiz, who had no fondness for hunting, remembered the trips with distaste, and recalled that on one occasion he was nearly shot by a casting director who had no idea how to properly handle a gun.

But ducks were just the beginning. In 1927 Zanuck took his wife Virginia on an African safari. In Kenya Darryl bagged a rhinoceros and posed for a photo with his wife, crouched beside the rhino’s carcass. Virginia, an erstwhile Mack Sennett bathing beauty and former leading lady to Buster Keaton, appears shaken. Her husband looks exhilarated. During this safari Zanuck also killed an elephant. He kept the animal’s four feet in his office on the Warners lot, and used them as ashtrays. If any animal lover dared to express dismay, the Hollywood sportsman would retort: “It was him or me, wasn’t it?” Zanuck made several forays to Canada with his coterie in this period, gunning for grizzly bears. Director William “Wild Bill” Wellman, who was more of an outdoorsman than Curtiz, once went along, but soon became irritated with Zanuck’s bullying. The two men got into a drunken fistfight the night before the hunting had even begun. In the course of the ensuing trip the hunting party was snowbound for three days; Zanuck sprained his ankle while trailing a grizzly; the horse carrying medical supplies vanished; and Wellman got food poisoning. “It was the damnedest trip I’ve ever seen,” the director said later, “but Zanuck loved it.”

Now that Zanuck had severed his ties with the Warner clan and was on the verge of a new professional adventure, a trip to Canada with a few trusted associates would be just the ticket. This time the destination would be a hunting ground on the banks of the Canoe River, a tributary of the Columbia River, 102 miles north of Revelstoke, British Columbia, a city about 400 miles east of Vancouver. There, in a remote scenic area far from any paved roads, telephones, or other niceties of modern life, the men could discuss Zanuck’s new production company and, presumably, their own potential roles in it. Present on the expedition were screenwriter Sam Engel, director Ray Enright, 42nd Street director Lloyd Bacon, producer (and former silent film comedian) Raymond Griffith, and director John G. Adolfi, best known at the time for his work with English actor George Arliss. Adolfi, who was around 50 years old and seemingly in good health, would not return.

II. The Director

Even dedicated film buffs may draw a blank when the name John Adolfi is mentioned. Although he directed more than eighty films over a twenty-year period beginning in 1913, most of those films are now lost. He worked in every genre, with top stars, and made a successful transition from silent cinema to talkies. He seems to have been a well-respected but self-effacing man, seldom profiled in the press.

According to his tombstone Adolfi was born in New York City in 1881, but the exact date of his birth is one of several mysteries about his life. His father, Gustav Adolfi, was a popular stage comedian and singer who emigrated to the U.S. from Germany in 1879. Gustav performed primarily in New York and Philadelphia, and was known for such roles as Frosch the Jailer in Strauss’ Die Fledermaus. But he was a troubled man, said to be a compulsive gambler, and after his wife Jennie died (possibly of scarlet fever) it appears his life fell apart. Gustav’s singing voice gave out, and then he died suddenly in Philadelphia in October 1890, leaving John and his siblings orphaned. (An obituary in the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent reported that Gustav suffered a stroke, but family legend suggests he may have committed suicide.) After a difficult period John followed in his father’s footsteps and launched a stage career, and was soon working opposite such luminaries of the day as Ethel Barrymore and Dustin Farnum. Early in the new century the young actor wed Pennsylvania native Florence Crawford; the marriage would last until his death.

When the cinema was still in its infancy stage performers tended to regard movie work as slumming, but for whatever reason John Adolfi took the plunge. He made his debut before the cameras around 1907, probably at the Vitagraph Studio in Brooklyn. There he appeared as Tybalt in J. Stuart Blackton’s 1908 Romeo and Juliet , with Paul Panzer and Florence Lawrence in the title roles. He worked at the Edison Studio for director Edwin S. Porter, and at Biograph in a 1908 short called The Kentuckian which also featured two other stage veterans, D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett. Most of Adolfi’s work as a screen actor was for the Éclair Studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, the first film capital. The bulk of this company’s output was destroyed in a vault fire, but a 1912 adaptation of Robin Hood in which Adolfi appeared survives. That same year he also appeared in a famous docu-drama, as we would call it, Saved from the Titanic. This ten-minute short premiered less than a month after the Titanic disaster, and featured actress Dorothy Gibson, who actually survived the voyage, re-enacting her experience while wearing the same clothes she wore in the lifeboat. (This film, unfortunately, is among the missing.) After appearing in dozens of movies Adolfi moved behind the camera.

Much of his early work as a director was for a Los Angeles-based studio called Majestic, where he made crime dramas, Westerns, and comedies, films with titles like Texas Bill’s Last Ride and The Stolen Radium. In 1914 the company had a new supervisor: D. W. Griffith, now the top director in the business, who had just departed Biograph. Adolfi was one of the few Majestic staff directors who kept his job under the new regime. A profile in the February 1915 issue of Photoplay describes him as “a tallish, good-looking man, well-knit and vigorous, dark-haired and determined; his mouth and chin suggest that their owner expects (and intends) to have his own way unless he is convinced that the other fellow’s is better.” It was also reported that Adolfi had developed something of a following as an actor, but that he dropped out of the public eye when he became a director. Presumably, that’s what he wanted.

Adolfi left Majestic after three years, worked at Fox Films for a time as a staff director, then freelanced. During the remainder of the silent era he guided some of the screen’s legendary leading ladies: Annette Kellerman (Queen of the Sea, 1918), Marion Davies (The Burden of Proof, 1918), Mae Marsh (The Little ‘Fraid Lady, 1920), Betty Blythe (The Darling of the Rich, 1922), and Clara Bow (The Scarlet West, 1925). Not one of these films survives. A profile published in the New York World-Telegram during his stint at Fox reported that Adolfi was well-liked by his employees. He was “reticent when the conversation turned toward himself, but frank and outspoken when it concerned his work. Mr. Adolfi is not only a director who is skilled in the technique of his craft; he is also a deep student of human nature.” Asked how he felt about the cinema’s potential, he replied, with unconscious irony, “it is bound to live forever.”

III. The Talkies

In spring of 1927 Adolfi was offered a job at Warner Brothers. His debut feature for the studio What Happened to Father? (now lost) was a success, or enough of one anyway to secure him a professional foothold, and he worked primarily at WB thereafter. Thus he was fortuitously well-positioned for the talkie revolution, for although talking pictures were not invented at the studio it was Sam Warner and his brothers, more than anyone else, who sold an initially skeptical public on the new medium. After Adolfi had proven himself with three talkie features Darryl Zanuck handed him an expensive, prestige assignment, a lavish all-star revue entitled The Show of Shows which featured every Warners star from John Barrymore to Rin-Tin-Tin.

Other important assignments followed. In March of 1930 a crime melodrama called Penny Arcade opened on Broadway. It was not a success, but when Al Jolson saw it he sensed that the story had screen potential. He purchased the film rights at a bargain rate and then re-sold the property to his home studio, Warner Brothers. Adolfi was chosen to direct, but was doubtless surprised to learn that Jolson had insisted that two of the actors from the Broadway production repeat their performances before the cameras. One of the pair, Joan Blondell, had already appeared in three Vitaphone shorts to good effect, but the other, James Cagney, had never acted in a movie. Any doubts about Jolson’s instincts were quickly dispelled. Rushes of the first scenes featuring the newcomers so impressed studio brass that both were signed to five-year contracts. While Adolfi can’t be credited with discovering the duo, the film itself, re-christened Sinners’ Holiday,remains his strongest surviving claim to fame: he guided Jimmy Cagney’s screen debut.

At this point the director formed a professional relationship that would shape the rest of his career. George Arliss was a veteran stage actor who went into the movies and unexpectedly became a top box office draw. He was, frankly, an unlikely candidate for screen stardom. Already past sixty when talkies arrived, Arliss was a short, dignified man who resembled a benevolent gargoyle. But he was also a journeyman actor, a seasoned professional who knew how to command attention with a sudden sharp word or a raised eyebrow. Like Helen Hayes he was valued in Hollywood as a performer of unblemished reputation who lent the raffish film industry a touch of Class, in every sense of the word.

In 1929 Arliss appeared in a talkie version of Disraeli, a role he had played many times on stage, and became the first Englishman to take home an Academy Award for Best Actor. Thereafter he was known for stately portrayals of History’s Great Men, such as Voltaire and Alexander Hamilton, as well as fictional kings, cardinals, and other official personages. The old gentleman formed a close alliance with Darryl Zanuck, whom he admired, and was in turn granted privileges highly unusual for any actor at the time. Arliss had final approval of his scripts and authority over casting. He was also granted the right to rehearse his selected actors for two weeks before filming began. All that was left for the film’s director to do, it would seem, would be to faithfully record what his star wanted. Not many directors would accept this arrangement, but John Adolfi, who according to Photoplay “was determined to have his own way unless he is convinced that the other fellow’s is better,” clearly had no problem with it. His first film with Arliss was The Millionaire, released in May 1931; and in the two years that followed Adolfi directed eight more features, six of which were Arliss vehicles. He had found his niche in Hollywood.

One of Adolfi’s last jobs sans Arliss was a B-picture called Central Park, which reunited the director with Joan Blondell. It’s a snappy, topical, crazy quilt of a movie that packs a lot of incident into a 58-minute running time. Central Park was something of a sleeper that earned its director positive critical notices, and must have afforded him a lively holiday from those polite period pieces for the exacting Mr. Arliss.

In spring of 1933, after completing work on the Arliss vehicle Voltaire, Adolfi accompanied Darryl Zanuck and his entourage to British Columbia to hunt bears. Arliss intended to follow Zanuck to his new company, while Adolfi in turn surely expected to follow the star and continue their collaboration. Things didn’t work out that way.

IV. The Hunting Trip

It’s unclear how long the men were hunting before tragedy struck. On Sunday, May 14th, newspapers reported that film director John G. Adolfi had died the previous week – either on Wednesday or Thursday, depending on which paper one consults – at a hunting camp near the Canoe River. All accounts give the cause of death as a cerebral hemorrhage. According to the New York Herald-Tribune the news was conveyed in a long-distance phone call from Darryl Zanuck to screenwriter Lucien Hubbard in Los Angeles. Hubbard subsequently informed the press. The N.Y. Times reported that the entire hunting party (Zanuck, Engel, Enright, Bacon, and Griffith) accompanied Adolfi’s remains in a motorboat down the Columbia River to Revelstoke. From there the body was sent to Vancouver, B.C., where it was cremated. Write-ups of Adolfi’s career were brief, and tended to emphasize his work with George Arliss, though his recent success Central Park was widely noted. John’s widow Florence was mentioned in the Philadelphia City News obituary but otherwise seems to have been ignored; the couple had no children.

V. The Aftermath

Darryl F. Zanuck went on to found Twentieth Century Pictures, a name suggested by his hunting companion Sam Engel. One of the company’s biggest hits in its first year of operation was The House of Rothschild, starring George Arliss and directed by Alfred Werker. The venerable actor returned to England not long afterwards and retired from filmmaking in 1937. In his second book of memoirs, published three years later, Arliss devotes several pages of warm praise to Zanuck, but refers only fleetingly to the man who directed seven of his films, John Adolfi, and misspells his name.

In 1935 Zanuck merged his Twentieth Century Pictures with Fox Films, and created one of the most successful companies in Hollywood history. He would go on to produce many award-winning classics, including The Grapes of Wrath, Laura, and All About Eve. Zanuck’s trusted associates at Twentieth-Century Fox in the company’s best years included Sam Engel, Raymond Griffith, and Lloyd Bacon, all survivors of the Revelstoke trip. Personal difficulties and vast changes in the film industry began to affect Zanuck’s career in the 1950s. He left the U.S. for Europe but continued to make films, and sporadically managed to exercise control over the company he founded. He died in 1979.

In 1984 a onetime screenwriter and film critic named Leonard Mosley, who had known Zanuck slightly, published a biography entitled Zanuck: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood’s Last Tycoon. Aside from his movie reviews most of Mosley’s published work concerned military matters, specifically pertaining to the Second War World. His Zanuck bio reveals a grasp of film history that is shaky at times, for the book has a number of obvious errors. Nevertheless, it was written with the cooperation of Darryl’s son Richard, his widow Virginia, and many of the mogul’s close associates, so whatever its errors in chronology or studio data the anecdotes concerning Zanuck’s personal and professional activities are unquestionably well-sourced.

When Mosley’s narrative reaches May 1933, the point when Zanuck is on the verge of founding his new company, we’re told that he and several associates decided to go on a hunting trip to Alaska. The location is not correct, but chronologically – and in one other, unmistakable respect – there can be no doubt that this refers to the Revelstoke trip. From Mosley’s book:

“There is a mystery about this trip, and no perusal of Zanuck’s papers or those of his former associates seems to elucidate it,” he writes. “Something happened that changed his whole attitude towards hunting. All that can be gathered from the thin stories that are still gossiped around was that the hunting party went on the track of a polar bear somewhere in the Alaskan wilderness [sic], and when the vital moment came it was Zanuck who stepped out to shoot down the charging, furious animal. His bullet, it is said, found its mark all right, but it did not kill. The polar bear came on, and Zanuck stood his ground, pumping away with his rifle. Only this time it was not ‘him or me,’ but ‘him’ and someone else. The wounded and enraged bear, still alive and still charging, swerved around Zanuck and swiped with his great paw at one of the men standing behind him – and only after it had killed this other man did it fall at last into the snow, and die itself. That’s the story, and no one seems to be able to confirm it nor remember the name of the man who died. The only certain thing is that when Zanuck came back, he announced to Virginia that he had given up hunting. And he never went out and shot a wild animal again, not even a jackrabbit for his supper.”

VI. The Coda

Was John Adolfi killed by a bear? It certainly seems possible, but if so, why didn’t the men in the hunting party simply report the truth? Even if their boss was indirectly responsible, having fired the shots that caused the bear to charge, he couldn’t be blamed for the actions of a dying animal. But it’s also possible the event unfolded like a recent tragedy on the Montana-Idaho border. There, in September 2011, two men named Ty Bell and Steve Stevenson were on a hunting trip. Bell shot what he believed was a black bear. When the bear, a grizzly, attacked Stevenson, Bell fired again – and killed both the bear and his friend.

That seems to be the more likely scenario. If Zanuck fired at the wounded bear, in an attempt to save Adolfi, and killed both bear and man instead, it would perhaps explain a hastily contrived false story. It would most definitely explain the prompt cremation of Adolfi’s body in Vancouver. Back in Hollywood Joe Schenck was busy raising money, and lots of it, to launch Zanuck’s new company. Any unpleasant information about the new company’s chief – certainly anything suggestive of manslaughter – could jeopardize the deal. A man hit with a cerebral hemorrhage in the prime of life is a tragedy of natural causes, but a man sprayed with bullets in a shooting, accidental or not, is something else again. That goes double if alcohol was involved, as it reportedly was on Zanuck’s earlier hunting trips.

Of course, it’s also possible that Adolfi did indeed suffer a cerebral hemorrhage. Like his father.

John G. Adolfi is a Hollywood ghost. Most of his works are lost, and his name is forgotten. (Even George Arliss couldn’t be bothered to spell it correctly.) Every now and then TCM will program one of the Arliss vehicles, or Sinners’ Holiday. Not long ago they showed Adolfi’s fascinating B-picture Central Park, that slam-bang souvenir of the early Depression years in which several plot strands are deftly inter-twined. One of the subplots involves a mentally ill man, a former zoo-keeper who escapes from an asylum and returns to the place where he used to work, the Central Park Zoo. He has a score to settle with an old nemesis, an ex-colleague who tends the big cats. As the story approaches its climax, the escaped lunatic deliberately drags his enemy into the cage of a dangerous lion and leaves him there. In the subsequent, harrowing scene, difficult to watch, the lion attacks and practically kills the poor bastard.

by William Charles Morrow

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

My sources for this article, in addition to the Mosley biography cited in the text, include Stephen M. Silverman’s The Fox That Got Away: The Last Days of the Zanuck Dynasty at Twentieth-Century Fox (1988), and Marlys J. Harris’s The Zanucks of Hollywood: The Dark Legacy of an American Dynasty (1989). For material on John Adolfi I made extensive use of the files of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Special thanks to James Bigwood for his prodigious research on the Adolfi family genealogy, and to Mary Maler, John Adolfi’s great-niece, for information she provided on her family.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Enrico Caruso was born on February 25, 1873. He was an Italian operatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) from the Italian and French repertoires that ranged from the lyric to the dramatic. One of the first major singing talents to be commercially recorded, Caruso made 247 commercially released recordings from 1902 to 1920, which made him an international popular entertainment star.

Caruso's 25-year career, stretching from 1895 to 1920, included 863 appearances at the New York Metropolitan Opera before he died at the age of 48. Thanks in part to his tremendously popular phonograph records, Caruso was one of the most famous personalities of his day, and his fame has endured to the present. He was one of the first examples of a global media celebrity. Beyond records, Caruso's name became familiar to millions through newspapers, books, magazines, and the new media technology of the 20th century: cinema, the telephone and telegraph.

Caruso toured widely both with the Metropolitan Opera touring company and on his own, giving hundreds of performances throughout Europe, and North and South America. He was a client of the noted promoter Edward Bernays, during the latter's tenure as a press agent in the United States. Beverly Sills noted in an interview: "I was able to do it with television and radio and media and all kinds of assists. The popularity that Caruso enjoyed without any of this technological assistance is astonishing."

Caruso biographers Pierre Key, Bruno Zirato and Stanley Jackson attribute Caruso's fame not only to his voice and musicianship but also to a keen business sense and an enthusiastic embrace of commercial sound recording, then in its infancy. Many opera singers of Caruso's time rejected the phonograph (or gramophone) owing to the low fidelity of early discs. Others, including Adelina Patti, Francesco Tamagno and Nellie Melba, exploited the new technology once they became aware of the financial returns that Caruso was reaping from his initial recording sessions.

Caruso made more than 260 extant recordings in America for the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor) from 1904 to 1920, and he and his heirs earned millions of dollars in royalties from the retail sales of these records. He was also heard live from the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in 1910, when he participated in the first public radio broadcast to be transmitted in the United States.

Caruso also appeared in two motion pictures. In 1918, he played a dual role in the American silent film My Cousin for Paramount Pictures. This film included a sequence depicting him on stage performing the aria Vesti la giubba from Leoncavallo's opera Pagliacci. The following year Caruso played a character called Cosimo in another film, The Splendid Romance. Producer Jesse Lasky paid Caruso $100,000 each to appear in these two efforts but My Cousin flopped at the box office, and The Splendid Romance was apparently never released. Brief candid glimpses of Caruso offstage have been preserved in contemporary newsreel footage.

While Caruso sang at such venues as La Scala in Milan, the Royal Opera House, in London, the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, and the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, he appeared most often at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, where he was the leading tenor for 18 consecutive seasons. It was at the Met, in 1910, that he created the role of Dick Johnson in Giacomo Puccini's La fanciulla del West.

Caruso's voice extended up to high D-flat in its prime and grew in power and weight as he grew older. At times, his voice took on a dark, almost baritonal coloration. He sang a broad spectrum of roles, ranging from lyric, to spinto, to dramatic parts, in the Italian and French repertoires. In the German repertoire, Caruso sang only two roles, Assad (in Karl Goldmark's The Queen of Sheba) and Richard Wagner's Lohengrin, both of which he performed in Italian in Buenos Aires in 1899 and 1901, respectively.

Repertoire

Caruso's operatic repertoire consisted primarily of Italian works along with a few roles in French. He also performed two German operas, Wagner's Lohengrin and Goldmark's Die Königin von Saba, singing in Italian, early in his career. Below are the first performances by Caruso, in chronological order, of each of the operas that he undertook on the stage.

World premieres are indicated with **.

L'amico Francesco (Morelli) – Teatro Nuovo, Napoli, 15 March 1895 (debut)**

Faust – Caserta, 28 March 1895

Cavalleria rusticana – Caserta, April 1895

Camoens (Musoni) – Caserta, May 1895

Rigoletto – Napoli, 21 July 1895

La traviata – Napoli, 25 August 1895

Lucia di Lammermoor – Cairo, 30 October 1895

La Gioconda – Cairo, 9 November 1895

Manon Lescaut – Cairo, 15 November 1895

I Capuleti e i Montecchi – Napoli, 7 December 1895

Malia (Francesco Paolo Frontini) – Trapani, 21 March 1896

La sonnambula – Trapani, 25 March 1896

Mariedda (Gianni Bucceri [it]) – Napoli, 23 June 1896

I puritani – Salerno, 10 September 1896

La Favorita – Salerno, 22 November 1896

A San Francisco (Sebastiani) – Salerno, 23 November 1896

Carmen – Salerno, 6 December 1896

Un Dramma in vendemmia (Fornari) – Napoli, 1 February 1897

Celeste (Marengo) – Napoli, 6 March 1897**

Il Profeta Velato (Napolitano) – Salerno, 8 April 1897

La bohème – Livorno, 14 August 1897

La Navarrese – Milano, 3 November 1897

Il Voto (Giordano) – Milano, 10 November 1897**

L'arlesiana – Milano, 27 November 1897**

Pagliacci – Milano, 31 December 1897

La bohème (Leoncavallo) – Genova, 20 January 1898

The Pearl Fishers – Genova, 3 February 1898

Hedda (Leborne) – Milano, 2 April 1898**

Mefistofele – Fiume, 4 March 1898

Sapho (Massenet) – Trento, 3 June (?) 1898

Fedora – Milano, 17 November 1898**

Iris – Buenos Aires, 22 June 1899

La regina di Saba (Goldmark) – Buenos Aires, 4 July 1899

Yupanki (Berutti)– Buenos Aires, 25 July 1899**

Aida – St. Petersburg, 3 January 1900

Un ballo in maschera – St. Petersburg, 11 January 1900

Maria di Rohan – St. Petersburg, 2 March 1900

Manon – Buenos Aires, 28 July 1900

Tosca – Treviso, 23 October 1900

Le maschere (Mascagni) – Milano, 17 January 1901**

L'elisir d'amore – Milano, 17 February 1901

Lohengrin – Buenos Aires, 7 July 1901

Germania – Milano, 11 March 1902**

Don Giovanni – London, 19 July 1902

Adriana Lecouvreur – Milano, 6 November 1902**

Lucrezia Borgia – Lisbon, 10 March 1903

Les Huguenots – New York, 3 February 1905

Martha – New York, 9 February 1906

Madama Butterfly – London, 26 May 1906

L'Africana – New York, 11 January 1907

Andrea Chénier – London, 20 July 1907

Il trovatore – New York, 26 February 1908

Armide – New York, 14 November 1910

La fanciulla del West – New York, 10 December 1910**

Julien – New York, 26 December 1914

Samson et Dalila – New York, 24 November 1916

Lodoletta – Buenos Aires, 29 July 1917

Le prophète – New York, 7 February 1918

L'amore dei tre re – New York, 14 March 1918

La forza del destino – New York, 15 November 1918

La Juive – New York, 22 November 1919

Caruso also had a repertory of more than 500 songs. They ranged from classical compositions to traditional Italian melodies and popular tunes of the day, including a few English-language titles such as George M. Cohan's "Over There", Henry Geehl's "For You Alone" and Arthur Sullivan's "The Lost Chord".

On 16 September 1920, Caruso concluded three days of recording sessions at Victor's Trinity Church studio in Camden, New Jersey. He recorded several discs, including the Domine Deus and Crucifixus from the Petite messe solennelle by Rossini. These recordings were to be his last.

Dorothy Caruso noted that her husband's health began a distinct downward spiral in late 1920 after he returned from a lengthy North American concert tour. In his biography, Enrico Caruso Jr. points to an on-stage injury suffered by Caruso as the possible trigger of his fatal illness. A falling pillar in Samson and Delilah on 3 December had hit him on the back, over the left kidney (and not on the chest as popularly reported). A few days before a performance of Pagliacci at the Met (Pierre Key says it was 4 December, the day after the Samson and Delilah injury) he suffered a chill and developed a cough and a "dull pain in his side". It appeared to be a severe episode of bronchitis. Caruso's physician, Philip Horowitz, who usually treated him for migraine headaches with a kind of primitive TENS unit, diagnosed "intercostal neuralgia" and pronounced him fit to appear on stage, although the pain continued to hinder his voice production and movements.

During a performance of L'elisir d'amore by Donizetti at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on December 11, 1920, he suffered a throat haemorrhage and the performance was canceled at the end of Act 1. Following this incident, a clearly unwell Caruso gave only three more performances at the Met, the final one being as Eléazar in Halévy's La Juive, on 24 December 1920. By Christmas Day, the pain in his side was so excruciating that he was screaming. Dorothy summoned the hotel physician, who gave Caruso some morphine and codeine and called in another doctor, Evan M. Evans. Evans brought in three other doctors and Caruso finally received a correct diagnosis: purulent pleurisy and empyema.

Caruso's health deteriorated further during the new year, lapsing into a coma and nearly dying of heart failure at one point. He experienced episodes of intense pain because of the infection and underwent seven surgical procedures to drain fluid from his chest and lungs. He slowly began to improve and he returned to Naples in May 1921 to recuperate from the most serious of the operations, during which part of a rib had been removed. According to Dorothy Caruso, he seemed to be recovering, but allowed himself to be examined by an unhygienic local doctor, and his condition worsened dramatically after that. The Bastianelli brothers, eminent medical practitioners with a clinic in Rome, recommended that his left kidney be removed. He was on his way to Rome to see them but, while staying overnight in the Vesuvio Hotel in Naples, he took an alarming turn for the worse and was given morphine to help him sleep.

Caruso died at the hotel shortly after 9:00 a.m. local time, on 2 August 1921. He was 48. The Bastianellis attributed the likely cause of death to peritonitis arising from a burst subphrenic abscess. The King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, opened the Royal Basilica of the Church of San Francesco di Paola for Caruso's funeral, which was attended by thousands of people. His embalmed body was preserved in a glass sarcophagus at Del Pianto Cemetery in Naples for mourners to view. In 1929, Dorothy Caruso had his remains sealed permanently in an ornate stone tomb.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

There Are No Secrets of Dumbledore Worth Adding to the World of Harry Potter

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

The sunk cost fallacy is a powerful thing. Despite the fact that the current pandemic has audiences more desperate than ever for tentpole films, no one has exactly been clamoring for the continuation of the Fantastic Beasts series, slated to have five movies in total. So it was with muted fanfare that Warner Bros. announced the upcoming release of the third Fantastic Beasts film, set to premiere in April 2022 under the title Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore. Those who watched The Crimes of Grindelwald will remember the prominent role of a young Dumbledore played by Jude Law—clearly the series isn’t quite finished exploring the famously eccentric wizard’s backstory. But given J.K. Rowling’s history of not knowing when to stop opening up the vault, unloading new factoids that simultaneously demystify the wizarding universe and cast its characters in a poor light, you have to wonder: Might everyone be better off if the secrets of Dumbledore were left untold?

The Fantastic Beasts series has never exactly set the world aflame with its brilliance. The initial film, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, approached the success of the original Harry Potter film series, earning $814 million on a $200 million budget. (Notably, it was the eighth highest grossing film in 2016, when each of the other Harry Potter films were in the top three highest grossing for their respective years.)

The final bait-and-switch reveal of Johnny Depp as the notorious Hitler-esque villain of the series did little to whet the appetites of moviegoers, and the second film fared considerably worse at the box office. The Crimes of Grindelwald made $150 million less than its predecessor, the worst showing of any Harry Potter film by far.

It was roundly criticized for its less than inspired plot and borderline offensive imagery surrounding some of the non-white characters. More than anything, audiences were turned off by the perceived pointlessness of the series: this was not an expansion of the Harry Potter universe that anyone was really asking for. And yet, the franchise soldiers on, kept alive more out of sheer bloody-mindedness than anything else. At this point, surely the kindest thing to do would be to put the poor dear out of its misery, releasing Eddie Redmayne from the shackles of a multi-million dollar contract and letting him go back to making inspirational period dramas. But as long as Rowling has life left in her body, she’s committed to tearing down her own legacy. So here we are: The Secrets of Dumbledore.

It’s no, well, secret that name-dropping Dumbledore in the title is a Hail Mary borne out of the desperate hope that evoking one of the most popular characters in the series will drive audiences back to the theaters. But realistically, it seems like Dumbledore’s backstory (and any hidden revelations contained within) has already been fairly well-mined. We’ve seen him as an old man, the wizened mentor of Harry Potter as headmaster of Hogwarts. We’ve seen him in flashbacks at various points in what we have to assume is an unusually extended middle age, thanks to Harry’s exploration of the Pensieve in an effort to learn more about Voldemort’s shadowy past. We’ve gotten first hand accounts of his early life from his brother Aberforth, and we’ve even read excerpts from an (admittedly potentially libelous) biography published posthumously by Bathilda Bagshot.

And now with The Crimes of Grindelwald, we’ve seen him as a roguishly handsome young Transfiguration professor at Hogwarts in the 1920s, thanks to Law in an impeccably tailored three-piece suit. Does Dumbledore even have any secrets left?

Setting aside all of the substantial on-screen exploration of Dumbledore’s past, we haven’t even begun to take into account one of the most powerful vessels of canonical Harry Potter intel: the famous Rowling info dump. Ever since Harry Potter put J.K. Rowling on the map, it’s been clear that she has veritable notebooks full of background information that didn’t make it into the books and films, and nothing delights her more than sharing some of these details. Some of them are puzzling but harmless, like the time she posted on Pottermore (apropos of nothing) that Hogwarts didn’t used to have indoor plumbing, and that witches and wizards simply relieved themselves wherever they stood and magically vanished the evidence.

Others add nuance to beloved characters: the revelation she shared shortly after the release of the final Harry Potter book, for example, which told us Dumbledore was gay. Learning all of this shapes our understanding of the series, but it also feels a little bit like a cheat. If it was important to Rowling that we know Dumbledore’s sexuality, why did she wait until after the ink was dry to tell us, and not simply include it in the text? In many ways, it’s a half measure; an opportunity to pay lip service to progressive values but without any inherent risk. (And the more that we learn about Rowling’s views on gender politics, the more it comes across as disingenuous.)

To be frank, audiences have reason to distrust Rowling’s attempts to elaborate on characters from the original series. Historically, this has not always improved said characters. Nagini, for instance, began as an intriguingly intelligent snake, one able to maintain a powerful bond to Voldemort when he was unable to connect with any of his own species in the same way. Everyone just sort of accepted that character as read, and no one asked for more of an explanation. The universe did not need a Nagini prequel.

But in The Crimes of Grindelwald, Rowling couldn’t resist the opportunity to tinker, and then we end up with a Nagini that is an incredibly problematic depiction of an Asian woman. She is enslaved by a circus owner and burdened with a blood curse that initially gave her the power to transform into a snake but, by the events of the original Harry Potter series, she is permanently fixed in snake form. Who in the world thought adding that to Nagini would make her a more compelling character? Proof that there is creative danger in becoming so rich and powerful as an artist that no one is willing to tell you, “No. That’s a bad idea.”

So while there are diehard fans out there, presumably thrilled by the news that the Fantastic Beasts franchise lives another day, there is a notable sense of dwindling enthusiasm amongst audiences at large. The Secrets of Dumbledore does little to inspire hope that this installment will prove itself worthy of existence, feeling more akin to a cynical attempt to capitalize on his popularity. Instead of making fans excited to learn more about the enigmatic Albus Dumbledore, it can’t help but evoke a feeling of dread. People still like Dumbledore, even with his questionable beliefs and actions in his early life, but what will happen when Rowling takes another swing at him?

No matter how much she intends to add to the character, there’s the very real risk she’ll take something away. Indeed, it seems obvious to everyone but the production team that she’s long since reached the point where the best thing for her own legacy would be for Rowling to put down the pen and walk away. Stop it before she does irreparable damage to the characters that a generation of children grew up with.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post There Are No Secrets of Dumbledore Worth Adding to the World of Harry Potter appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3EMU9qg

2 notes

·

View notes

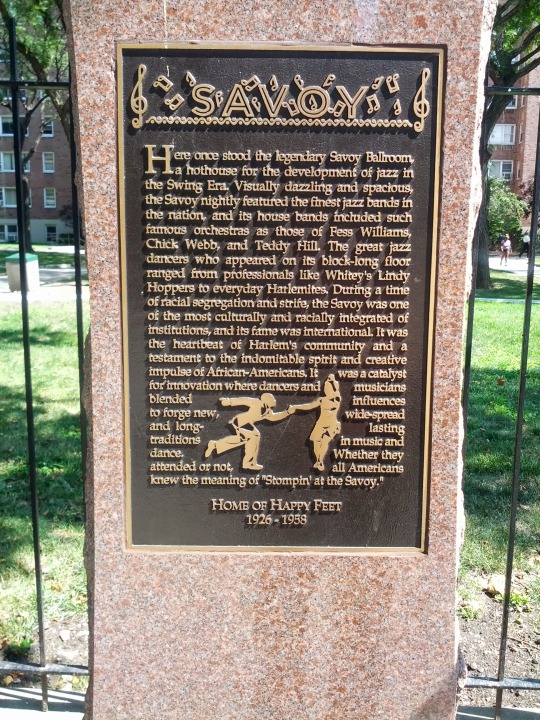

Photo

The Savoy Ballroom was a large ballroom for music and public dancing located at 596 Lenox Avenue, between 140th and 141st Streets in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. Lenox Avenue was the main thoroughfare through upper Harlem. Poet Langston Hughes calls it the Heartbeat of Harlem in Juke Box Love Song, and he set his work "Lenox Avenue: Midnight" on the legendary street. The Savoy was one of many Harlem hot spots along Lenox, but it was the one to be called the "World's Finest Ballroom". It was in operation from March 12, 1926, to July 10, 1958, and as Barbara Englebrecht writes in her article "Swinging at the Savoy", it was "a building, a geographic place, a ballroom, and the 'soul' of a neighborhood". It was opened and owned by white entrepreneur Jay Faggen and Jewish businessman Moe Gale. It was managed by African-American business man and civic leader Charles Buchanan. Buchanan, who was born in the British West Indies, sought to run a "luxury ballroom to accommodate the many thousands who wished to dance in an atmosphere of tasteful refinement, rather than in the small stuffy halls and the foul smelling, smoke laden cellar nightclubs ..."

The Savoy was modeled after Faggen's downtown venue, Roseland Ballroom. The Roseland was a mostly white swing dance club. With swing's rise to popularity and Harlem becoming a connected black community, The Savoy gave the rising talented and passionate black dancers an equally beautiful venue. The ballroom, which was 10,000 square feet in size, was on the second floor and a block long. It could hold up to 4,000 people. The interior was painted pink and the walls were mirrored. Colored lights danced on the sprung layered wood floor. In 1926, the Savoy contained a spacious lobby framing a huge, cut glass chandelier and marble staircase. Leon James is quoted in Jazz Dance as saying, "My first impression was that I had stepped into another world. I had been to other ballrooms, but this was different – much bigger, more glamour, real class ..."

The Savoy Ballroom was named after the Savoy Hotel in London as those who named the ballroom felt this gave the ballroom a classy, upscale feeling, as the hotel is a very elite, upscale hotel.

The Savoy was popular from the start. A headline from the New York Age March 20, 1926, reads "Savoy Turns 2,000 Away On Opening Night – Crowds Pack Ball Room All Week". The ballroom remained lit every night of the week.

The Savoy had the constant presence of the best Lindy Hoppers, known as "Savoy Lindy Hoppers". Occasionally, groups of dancers such Whitey's Lindy Hoppers turned professional and performed in Broadway and Hollywood productions. Whitey turned out to be a successful agent, and in 1937 the Marx Brothers' movie A Day at the Races featured the group. Herbert White was a bouncer at the Savoy who was made floor manager in the early 1930s. He was sometimes known as Mac, but with his ambition to scout dancers at the ballroom to form his own group, he became widely known as Whitey for the white streak of hair down the center of his head. He looked for dancers who were "young, stylized, and, most of all, they had to have a beat, they had to swing".