#center for netherlandish art at the museum of fine arts

Text

al things considered — when i post my masterpiece #1133

first posted in facebook november 13, 2022

michaelina wautier -- "self-portrait" (ca. 1649)

"we knew nothing about her. as a specialist working in the field, i didn’t know she existed" ... christopher atkins (director of the center for netherlandish art at the museum of fine arts)

"'it’s really pretty amazing,' said atkins, describing how art historians have traditionally focused on male artists from the era. 'how did we miss these things as a field for so long?'" ... malcolm gay

"i wonder if institutions know it is a problem. there is a lot of discussion about women having more exhibitions, so from the outside it seems like we are celebrating women of different ages. but i wonder if institutions realize that there needs to be a lot more work done. maybe they don’t understand how imbalanced it is" ... naima keith (vice president of education and public programs, los angeles county museum of art)

"the explanation that women [are poorly represented because they] have often decided to leave the art world? i don’t believe that for a minute. i think there have been women working hard in the art world forever and if we haven’t seen them, then shame on us" ... brooke davis anderson (director, the museum at the pennsylvania academy of the fine arts)

"i call bullshit on the idea that it takes a while [to see change]. how much more time does it take? if a new generation of art historians and curators have to be resensitized to this then my god, we have amnesia at this point" ... michelle millar fisher, (curator of contemporary decorative arts, museum of fine arts, boston)

"well, first of AL, i probably would fire christopher atkins (the alleged director of the NETHERLANDISH art at the museum of fine arts here in boston) IF he really did not even know that a master from the 'dutch golden age' like wautier even existed" ... al janik

#michaelina wautier#self-portrait#christopher atkins#art historians#center for netherlandish art at the museum of fine arts#boston#malcolm gay#female artists#naima keith#institutions#los angeles county museum of art#brooke davis anderson#museum at the pennsylvania academy of the fine arts#women artists#shame#michelle millar fisher#museum of fine arts#bullshit#al things considered

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

X-radiograph(s) of "Way to Calvary and Pieta (Diptych)", Harvard Art Museums: Photographs

X-Radiograph Description: Negative Burroughs Number: 720 X-Radiograph(s) of: Artist: Master of the Braunschweig Diptych, Netherlandish, act. late 15th century Title: Way to Calvary and Pieta (Diptych) Owner: Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussel... Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Alan Burroughs Collection of X-Radiographs

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/344431

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MWW Artwork of the Day (7/22/19)

Dirck van Baburen (Dutch, 1595–1624)

The Procuress (1622)

Oil on canvas, 102 x 108 cm.

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts (Theresa Hopkins Fund)

The Utrecht School painters specialized in close-up views of large, half-length figures, solidly modelled with emphatic contrasts of light and shadow. Here, an amorous suitor barters with an elderly, turbanned woman for the favors of a cheerful young woman. The lute, symbol of love, occupies the center of the composition; the gestures of the hands that surround it tell the painting's story.

From the end of the 1620s paintings containing a clear allusion to sensuality and sexuality increased. Such allusions had been present in an embryonic stage in sixteenth-century Venetian painting. But the authors of these seventeenth-century paintings were not Italian -- Italians were evidently inhibited by the Catholic Church's view of morality. Once Netherlandish artists returned to the Low Countries they developed a particular interest in scenes which combined seduction and music. The success of this combination is demonstrated by the sheer number of paintings that have survived. Baburen's painting is an example of this new genre, Honthorst's "Procuress" being another.

1 note

·

View note

Text

usse 55

Floral Patterns ~ An Essay About Flowers and Art (with a Blooming Addendum.)

Share

by Andrew Berardini

A Change of Heart installation view at Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Los Angeles, 2016. Courtesy: Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Michael Underwood

“Without flowers, the reptiles, which had gotten along fine in a leafy, fruitless world, would probably still rule. Without flowers, we would not be.”

— Michael Pollan, The Botany of Desire (2001)

“Not even the category of the portrait seems to have ever attained the profound level of painterly decrepitude that still life would attain in the sinister harmlessness in the work of Matisse or Maurice de Vlaminck… the most obsolete of all still-life types.”

— Benjamin H. D. Buchloh on Gerhard Richter’s Flowers (1992)

Don’t worry, nobody’s looking. Go ahead.

Stop and smell the flowers.

Feel that sumptuous perfume blooming from those spreading petals. That’s pleasure. That’s sex. That’s the body lotion of the teenage beauty fingering your belt buckle to take your virginity (or the one you wore when you tugged that belt off your first). That’s your grandmother’s bathroom and the heart-shaped wreath at her funeral. That’s the lithe fingers and supple wrists of the florist, an emperor of blooms arranging the flowers for your mother just so.

Those petals, that scent, those colors.

Somehow flowers have become a decrepit subject, “the most obsolete of all still-life types,” to use Buchloh’s words. Despite the eminent Octoberist’s antipathy (and he is hardly alone in his disdain), flowers in art are back in bloom.

Flagrantly frivolous, wholly ephemeral, though ancient in art, the floral’s recent return as a major subject for artists marks a pivot toward those things that flowers represent: the decorative, the minor, the ephemeral and emotional, the liveliness of their bloom and the perfume of their decay, a sophisticated language of purest color and form that can be both raw nature and refined arrangement, poetic symbolism rubbing against the political mechanisms of value, history, and trade. Flowers are fragrant with subtle meanings, each different for every artist who chooses them as a subject. They are a move away from literal explications, self-righteous cynicism—and toward what, precisely? Let’s say poetry.

Bas Jan Ader, Primary Time (still), 1974. © Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Andersen, 2016 / Bas Jan Ader by SIAE, Rome, 2016. Courtesy: Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles

Free in the wilderness, rowed in gardens, in bouquets on tables, or as a decorative aromatic around the dead, flowers offer an opportunity for a simple, sensual pleasure—both a temporary escape and a corporeal return. Their origins as a species are a bit shrouded in mystery, but most who study flowers and evolution agree that they came about in order to employ insects and animals in their reproduction (a process that surely continues with our artful interventions). They lure with beauty, eventually tricking humans into agriculture and the dream of making such fecund and lively yearnings permanent, into art.

First and foremost, flowers are the sex organs of plants. Those bright colors and elaborate bodies were meant to turn us on. Georgia O’Keeffe transformed her blossoms from still-life representation into a kind of abstraction that tongued that first truth of flowers; all of her blooms wore the faces of interdimensional pussies. Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of flowers look even more suggestive to me than some of his more obviously lusty snaps of men in various states of undress and erect action.

Though their flounce and curve have a pornography of color, flowers as a metaphor can be easily read as safe, sanitized stand-ins for the real musk and squelch of sex. A vase of flowers in grandma’s parlor might be less notable than a bouquet of dildos erupting out of a bucket of lube. The opposite of badass to all the tough boys playing with their power tools, flowers to them are for old ladies and sissies and girls. Macho minimalists preferred stacks of bricks and sheets of steel to prove the heft of their seriousness. Besides, the florals look too comfortably bourgeois for the shock and spectacle of self-serious avant-gardists, though Giacomo Balla’s Futurist Flowers(1918-1925) look as radical as anything else those defiant Italians cooked up.

Virginia Poundstone: Flower Mutations installation view at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, 2015. Courtesy: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield. Photo: Jean Vong

Though flowers have appeared in art for thousands of years, first evidenced in funerary motifs in the earliest Egyptian dynasties, they’ve been used mostly as a sideshow, a decorative motif, a signifying prop. But around 1600, during the time of the tulip mania that rubbled the Netherlandish economy, Dutch artists began to paint blooms as the main attraction: finely wrought bouquets with delicate strokes, an idealistic botanist’s attention to perfection and detail, each variety laden with meaning, some held over from religion, some devised for newly invented varietals. This efflorescence came about with the disposable income of the bourgeoisie and the introduction of the tulip to international trading with the Ottoman Empire; in the court of Constantinople, flowers were all the rage. As an object of desire and prestige, the flower earned its worth as a central subject.

By the Victorian era, the language of flowers became wildly popular, as that repressed period needed something sexy to finger, especially for the corseted women. The frivolity of flowers was perhaps an area of knowledge the patriarchy let ladies have mastery over, but male artists weren’t ignoring the chromatic potential of blooms, either. With wet smears and hazy visions, Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet were among the best floral daubers of their time (with a solid shout out to the drooping beauties of Henri Fantin-Latour, whose 1890 painting A Basket of Flowers made it onto New Order’s 1983 album Power, Corruption, and Lies, itself an elliptical Richter reference). Flowers to these painters were a way to explore the power and range of their medium with unfettered color. “Perhaps I owe it to flowers,” said Monet, “that I became a painter.” As art took an intellectual turn, however, flowers fell out as serious subjects and became the provenance of Sunday painters, appropriate only for the marginalized. Yet as outsiders increasingly collapse binaries, the center cannot hold and vines snake into the heart of power to bloom a variety as diverse and beautiful as the spectrum of humanity.

A Change of Heart, an exhibition organized by the curator Chris Sharp at Hannah Hoffman Gallery in Los Angeles in summer 2016, touched on dreams and contemplations I’d been having about obvious forms of beauty and their force in art as both assertion and escape. Sunsets, moonlight, waterfalls, and, of course, flowers, all easily dismissed as sentimental kitsch, seemed to be enjoying a new life, born of a self-conscious romanticism that acknowledges these subjects as perhaps decayed and misspent, but lets their beauty sweep them up anyway. Sharp stated in the press release that the work in the exhibition “embraces the floral still life in all its formal, symbolic, political and aesthetic heterogeneity… a radical and even dizzying diversity of approaches, including the queer, the decorative, the scientific, the euphemistic, the memento mori, the painterly, the deliberately amateur and minor as a position, and much more.”[1]

Willem de Rooij, Bouquet IX, 2012. Courtesy: the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Michael Underwood

From historical works by Andy Warhol, Alex Katz, Ellsworth Kelly, Jane Freilicher, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Bas Jan Ader to art made much more recently by Camille Henrot, Willem de Rooij, Amy Yao, Kapwani Kiwanga, and Paul Heyer, the pieces in A Change of Heart approach the floral in wholly unique ways. Rather than cordoning off the artists in Sharp’s excellent show, I’m going to weave their methods, ideas, and visions into a larger conversation, some aspects of which were quite likely on the curator’s mind, as any art gallery and its resources can only be so expansive. In London as well, the gallerist and curator Silka Rittson-Thomas has opened up a project space and storefront called TukTuk Flower Studio to host the floral visions of contemporary artists.

Of course some artists in recent history focus on the base, mass appeal of flowers, like Warhol and his iconic screenprint Flowers (1964), or Jeff Koons with his giant, bloom-encrusted Puppy(1992) and solid shimmering metal of Tulips (1995-2004). But despite the blank-faced games of pop cipher employed by Warhol and the spirited industrial-scale exuberance of Koons, I can’t help finding a whisper of contempt in both, a pandering hucksterism, giving the people what they want. This obviousness and its exploitation is of course a part of the story of our modern interactions with flowers, but it obscures a more nuanced narrative.

Capitalism has so often turned beauty as a notion into kitsch, or as Milan Kundera puts it, “a denial of shit,” and we can find this modern kitsch in the unblemished bloom on the cheeks of a Disney princess, or in “America’s most popular artist” Thomas Kinkade’s creation of an imagined past of perfect old-timey townships, a good old days that glosses over all the problems of inequality and oppression endemic to that era. Donald Trump is the kingpin of this kind of kitsch these days. The best of our feelings can be easily hijacked for political purposes, but it is a mistake to cynically dismiss those feelings simply because others would take advantage of them.

All aspects of creation are beautiful enough to need little human improvement, including flowers. As John Berger writes in The White Bird, “The notion that art is the mirror of nature is one that appeals only in periods of skepticism. Art does not imitate nature, it imitates a creation, sometimes to propose an alternative world, sometimes simply to amplify, to confirm, to make social the brief hope offered by nature.” [2] We attempt to capture the power of these moments not to improve upon them, but to fix their power, to make ephemeral hopes and desires into something more permanent. Perhaps the natural versus the human-made is one more collapsing binary, and the diversity of flowers allows for such wild variety that the simple monolithic subject of “flowers” can’t easily contain it. In using flowers as a subject, artists have gravitated from the classic still life (like Richter on the ass end of Buchloh’s anti-floral sentiment), with its entwined poetical and political meanings and their elaborate symbolic language, operating at the decorative margins, toward the center. This can be traced in the atmospheric floral patterns of Marc-Camille Chaimowicz (enjoying a fantastic resurgence of interest), the pastel squiggles of Lily van der Stokker, and the softly erotic washes of Paul Heyer. Pulling the margins into the center is also of course one of the great political projects of our time.

Felix Gonzales-Torres, “Untitled” (Alice B. Toklas’ and Gertrude Stein’s Grave, Paris), 1992.

© The Felix Gonzales-Torres Foundation. Courtesy: Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

The poetical-political intertwining in flowers has a few significant contemporary exemplars. Felix Gonzalez-Torres imbued common objects with profound poetic and political force throughout his work, and included in A Change of Heart was his photograph of the flowers on the graves of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. In a single snap, an almost slight touristic photograph, the artist reveals a nexus of forces around flowers: as memorial, as assertion of love with all its political and artistic forces, as vaginal (given their lesbian sexuality), and as a visual poem that matches Stein’s “A rose is a rose is a rose…,” itself of course an invocation of William Shakespeare’s “A rose by any other name would smell just as sweet.” A rose is a rose and love is love, by any other name.

With a blend of flowers, sometimes artificially constructed, and his own indexical variety of sharp critique, Christopher Williams takes a more distinctly political focus, working wholly on reclassifying a collection of flower models (fakes, to be clear) not into botanical hierarchies but into political relevance. The photographs in Angola to Vietnam* (1989) are snapped pictures of selected replicas from the Harvard Botanical Museum’s Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models, made between 1887 and 1936. Williams, however, focuses on flowers from countries where political disappearances were recorded in 1985, reclassifying them by country of origin rather than by the museum’s system. But although these are certainly flowers, one gets the feeling that Williams wants to undermine their bourgeois beauty and the colonial impulse that collected, modeled, and classified them.

This sharply political act finds force in Taryn Simon’s photo series Paperwork and the Will of Capital (2015) and Kapwani Kiwanga’s ongoing series Flowers for Africa (begun in 2012), with their similar focus on floral arrangements made for banquets celebrating important political moments. Simon’s pictures tend to flatten the arrangements into manipulated environments. Kiwanga presents living bouquets, with the intention that they rot over the course of the exhibition (I watched one whither in A Change of Heart) so as to describe a complex physical poetic. For Kiwanga, the flowers that stood on the tables of important moments in politics represent the colonial import of European flower arrangement: where, for what, and by whom these flowers were cultivated, but also the hope and heartbreak involved in many of the agreements they witnessed. Some represented a marked turn toward liberation, while other accords withered along with the flowers. (Both of these projects echo, for me, Danh Vo’s display of the chandeliers from the Hotel Majestic in Paris hanging over the agreement that ended the US-Vietnam War.)

Zoe Crosher, The Manifest Destiny Billboard Project in Conjuction with LAND, Fourth Billboard to Be Seen Along Route 10, Heading West… (Where Highway 86 Intersects…), 2015. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Chris Adler

Zoe Crosher’s billboard series Shangri LA’d (2013-2015), produced in collaboration with LAND, displayed a lush array of flowers and greenery arranged by the artist and shot in a storefront in Los Angeles’s Chinatown formerly occupied by the Chinese Communist Party. As one drove across the country on the transcontinental highway, I-10, the flowers rotted further with each successive picture, until a decayed brown mass greeted the traveler as they crossed into California and on to Los Angeles. The dream of prosperity and possibility that drives a traveler westward became the hardships of the road and the realities of the place.

For the last decade, Virginia Poundstone has included in her artwork all aspects of floral cultivation. She has climbed the Himalayan mountains to find the wildest of wildflowers, and traveled to the factory farms of Colombia, tracing industrially grown blooms from growth to auction to wholesalers to flower markets and shops. Her interest grew from her day job as a floral arranger and her research into the gendered origins of that craft in the West and its resonance as a mode of art making in Japanese ikebana. She has also curated exhibitions at the Aldrich Museum that included floral works by Christo, Nancy Graves, and Bas Jan Ader (Ader’s video Primary Time [1974], of endless arrangements, is also in A Change of Heart) that have informed her deep investigations into the complex symbolism and language of flowers.

Other artists focus primarily on this language. Willem de Rooij’s Bouquet series (first begun with his late collaborator, Jeroen de Rijke, in 2002) speaks without literal language. Discussions around politics are followed by meditations on color or a collection of blooms gathered for their intensely allergenic qualities. The giant displays, in contrast to Kiwanga’s, are carefully maintained throughout an exhibition; a florist collaborator always makes regular visits to an exhibition to maintain the scent, color, and freshness of the expression.

In A Change of Heart, Sharp also included Camille Henrot’s ikebana interpretations of important modern novels as well as Maria Loboda’s A Guide to Insults and Misanthropy (2006), which attempts to use the symbolic language of flowers to insult their receiver.

Camille Henrot, The Golden Notebook, Doris Lessing, 2014. Courtesy: the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

For flowers, the recent turn holds an echo of romanticism, the intuitive, the emotional, the poetic, existing alongside a belief in political freedoms. The lusty poet Lord Byron died in the war for Greek independence. One of the fundamental human rights is a right to pleasure, to beauty. Beauty isn’t our collective ignoring of the hard struggles of the world, but rather an assertion of exactly what we’re fighting for.

As Fernando Pessoa writes in The Book of Disquiet (1984), “Flowers, if described with phrases that define them in the air of the imagination, will have colours with a durability not found in cellular life. What moves lives. What is said endures.”[3]

[1] http://hannahhoffmangallery.com/media/files/pr_acoh_web.pdf.

[2] John Berger, The White Bird (London: Chatto & Windus, 1985)

[3] Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet (London: Serpent’s Tale, 1991)

~ BLOOMING ADDENDUM ~

Christopher Williams, Angola, 1989, Blaschka Model 439, 1894, Genus no. 5091, Family, Sterculiaceae Cola acuminate (Beauv.) Schott and Endl., Cola Nut, Goora Nut, 1989, from the series Angola to Vietnam*, 1989.

Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Orchid / #DA70D6

General Sternwood: The orchids are an excuse for the heat. You like orchids?

Marlowe: Not particularly.

General Sternwood: Nasty things. That flesh is too much like the flesh of men. Their perfume has a rotten sweetness of corruption…

— The Big Sleep (1946)

The shape of this flowering plant’s pendulous doubled root ball suggested to some ancient Hellenic botanist the particular danglers in a man’s kit, and the orchid got its name from the Greek word for testes. Thus the dainty beloveds of aristocratic gardeners and fussy flower breeders are buried balls, dirty nuts. Try not to snicker when granny effuses, “I simply adore orchids.” Flowers have always been symbolic of sexuality, and even more so for those for whom it’s suppressed. Women, especially older ones, have been forced by social norms to stanch their desires, rarely granted the allowance to fuck freely. It gladdens the heart in its own weird way to hear old folks homes have the highest rates of STDs these days. Not because it’s good for anyone to catch the clap, but because it means they fuck with more abandon than most might care to admit.

To some, orchids are the sexiest of flowers. Their namesake roots lie buried in most variants, while those strange blooms pump horticultural hearts with lively colors, generous curves, and lusty orifices. If vaginal decoration took a sharp surgical turn past bejeweled vajazzling, you might find yourself confronted with one of these psychedelic pussies when dipping down for a French lick. As flowers, they fall into an uncanny valley. Too close but not close enough, the effect is just creepy rather than alluring. While other flowers invite an inserted nose, a huff, and though not yet an erection, their floral perfume has turned my head in that general direction. But the fleshy orchid does not inspire my lusts even a little. Perhaps even the opposite—its odor and form the absence of body, a dry, funereal thing.

“Crypt orchid” is the term for an undescended testicle, though I dream a flower that can only blossom in tombs.

The bright, rich purple creeps its name from the flower, one of innumerable possibilities for a plant with wild variation. Though it has the crackle of electricity beneath its buzz, orchid’s too muted to be much beyond a suggestion. Bright but not the brightest, rich without being creamy, orchid’s a faded purple haze on a bright day, the fading neon of a strip club past its prime.

Rose / #FF007F

A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.

When a beautiful rose dies beauty does not die

because it is not really in the rose.

— Agnes Martin (1989)

Each five-petal-kiss of colors from the tangled, toothy green stems. A brokenhearted smear, a yearning expressed through the formality of its presentation, the rose’s simple obviousness is its charm. The color of nipple, just exposed before cold air and hot mouths harden it into a deeper shade.

In many languages, the words for “rose” and “pink” are the same.

Rose-colored glasses. Roseate glow.

Rose tints my world

Keeps me safe from my trouble and pain.

— The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

Ask any florist and he’ll know how much a dozen will cost, one extra thrown in for luck. The rose grows thorns to better climb over its neighbors, to push over other flowers hungry for a beam of sunlight. More than one rose has drawn my blood, the dripping finger quickly mouthed.

Rose, floating in the pond, a dead flower in the eddies of the silver surface spangled with light. A lover’s bathtub blanket, a romantic’s bedspread. Rose, a gesture, an empty signifier, a lover’s lament, a husband’s apology. A shapely scented flower, a dream of what pussies could be.

Flowers and fruits are the sex organs of plants. Georgia O’Keeffe knew surely what she was doing with her folded blooms, plumped petals peeled back. Victorian ladies corseted by rigid morality spent repressed hours devotedly fingering their carefully cultivated flowers. Fresh blossoms will wilt on the vine whether they are nabbed or not. Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, you virgins who make much of time. The scientific term for wilted plants starved of nutrients and water is “flaccid.”

A lover once told me she only enjoyed flowers knowing that something was dying expressly for her pleasure.

Every rose has its thorn…

Flowers began as a funeral tradition to mask the odor of a decaying corpse. Wreathed, bouqueted, and sprayed, apple blossoms and heliotropes, chrysanthemums and camellias, hyacinths and delphiniums, snapdragons and, of course, roses. Anything goes for funeral flowers, just as long as they are fresh.

One artist I know dreamed of casting in concrete the cast-off flowers at the base of a Soviet war memorial. All the original flowers she stared at for hours, snapping picture after picture, measuring and admiring the perfect war memorial, the waste of pageantry all heaped and rotting, all the showy pomp to be swept up and trashed. Failing to gather them all from a park one Sunday afternoon, she made a memorial to that one. Under marbles carved Pro Patria, sometimes you’ll find flowers, but you’ll be sure to find a corpse.

“Roses,” she thought sardonically, “All trash, m’dear.”

— Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway (1925)

As bright blooms fade, what is the color of decay?

Is it a sinking brown, a pale green, a moldy black that captures the wilted flower, the rotten fruit, the decomposing body? Spotted and mottled, both wet and dusty, alive with death’s critters and aromatic with rot, the color is unsteady at best, a hue with a checkered future. Tuck a rose away, let it dry, and though the life goes and the color fades, its form remains.

Ah Little Rose—how easy

For such as thee to die!

— Emily Dickinson (1858)

I won’t forget to put roses on your grave.

Lilac / #CBA2CB

I lost myself on a cool damp night

Gave myself in that misty light

Was hypnotized by a strange delight

Under a lilac tree

I made wine from the lilac tree

Put my heart in its recipe

It makes me see what I want to see

and be what I want to be

When I think more than I want to think

Do things I never should do

I drink much more than I ought to drink

Because it brings me back you…

Lilac wine is sweet and heady, like my love

Lilac wine, I feel unsteady, like my love

Pale purples are the fucking saddest. Lavender’s forgetful wash. Mauve’s lonely decadence. And lilac. The color of unwilling resignation to lost passion. The pale fade, a lost spring.

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

—T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land (1922)

The lilac flower originated on the Croatian coast whence it found its way into the gardens of Turkish emperors and from there to Europe in the 16th century, not reaching the Americas until the 17th. The scent of lilac has become for many the scent of spring. Carried by the compound indole, which is also found in shit, lilac’s aroma carries with its fade a special decay, heavy and narcotic. To a nose that does not know the tricks of the master perfumer, indole dropped in chocolate and coffee makes a product smell natural.

A note found in perfume, bottled spring, often worn by elderly ladies. In the Descanso Gardens near Los Angeles, there is a grove of two hundred fifty varieties of lilac, their names a horticulturist’s poetry of yearning: Dark Night and Sylvan Beauty, Snow Shower and Spring Parade, Maiden’s Blush and Vesper Song.

I missed their bloom this year, gone to the snowy mountains where the flowers blossom late, but to walk among the towering shrubs is to be punched in the face with perfume. So sweet, so heady. Running my fingers over its heart-shaped leaf, failing to feel my leaf-shaped heart. I dreamed of going to the gardens with my lover and went there many times after she left me. Dreaming of her. Feeling the sweet sadness of her perfume, the unwilling resignation of her love withdrawn. And this lover, all the lovers who always go away. One lilac may hide another and then a lot of lilacs…

— Kenneth Koch (1994)

Walt Whitman dropped a sprig on the passing coffin of a murdered president and birthed a poem for dooryards and students. Not his most beautiful by far, but its love is real. As any love for a distant leader can only be so real, but the lilac is love. Staring into a screen full of its color, I am both spring and its destruction. Its bright lovely burst of life, its wilt and loss. The cool kiss of night, naked skin shivers but still you stay. And you stay and drink its sweetness and its rot, you drink your heart.

In the desert

I saw a creature, naked, bestial,

Who, squatting upon the ground,

Held his heart in his hands,

And ate of it.

I said, “Is it good, friend?”

“It is bitter—bitter,” he answered;

“But I like it

Because it is bitter,

And because it is my heart.”

— Stephen Crane (1895)

Cherry Blossom / #FFB7C5

A Selection of the Traditional Colors of Japan;

or, Bands I Wished I Was In

Cherry Blossom

Ibis Wing

Long Spring

Dawn

Orangutan

Persimmon Juice

Cypress Bark

Meat

Sparrow Brown

Decaying Leaves

Pale Incense

The Brown of Flattery

The Color of an Undried Wall

Golden Fallen Leaves

Simmered Seaweed

Contemplation in a Tea Garden

Pale Fallen Leaves

Underside of Willow Leaves

Sooty Willow Bamboo

Thousand-Year-Old Green

Insect Screen

Rusty Storeroom

Velvet

Harbor Rat

Iron Storage

Mousy Wisteria

Thin Color

Fake Purple

Vanishing Red Mouse

Half Color

Inside of a Bottle

Andrew Berardini is an American writer known for his work as a visual art critic and curator in Los Angeles. He has published articles and essays in publications such as Mousse, Artforum, ArtReview, Art-Agenda.

Originally published on Mousse 55 (October–November 2016)

0 notes

Photo

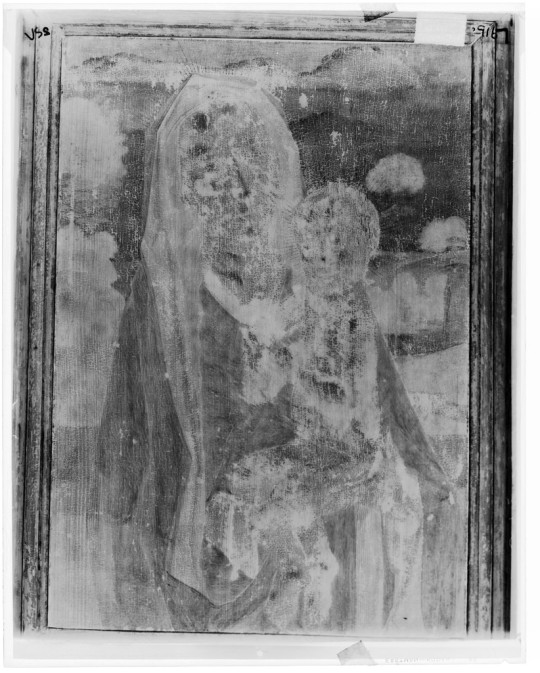

X-radiograph(s) of "Virgin and Child", Harvard Art Museums: Photographs

X-Radiograph Description: Negative Burroughs Number: 916 X-Radiograph(s) of: Artist: Goes, Hugo van der, Netherlandish, ca.1440-1482 Title: Virgin and Child Owner: Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium Object Number: 957 Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Alan Burroughs Collection of X-Radiographs

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/344626

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

X-radiograph(s) of "Portrait of William Moreel", Harvard Art Museums: Photographs

Burroughs Number: 1371 X-Radiograph(s) of: Artist: Memling, Hans, Early Netherlandish, ca.1433-1494 Title: Portrait of William Moreel Owner: Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium Object Number: 292 Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Alan Burroughs Collection of X-Radiographs

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/345077

0 notes

Photo

X-radiograph(s) of "St. Sebastian", Harvard Art Museums: Photographs

X-Radiograph Description: 2 details Burroughs Number: 1378 X-Radiograph(s) of: Artist: Memling, Hans, Early Netherlandish, ca.1433-1494 Title: St. Sebastian Date: early Owner: Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium Object Number: 291 Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Alan Burroughs Collection of X-Radiographs

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/345084

0 notes