#chateau de Montmorin

Text

Château de Montmorin. Shot on Rollei Superpan 200 with an IR filter.

#analog#photography#filmisnotdead#film photography#medium format#120 film#microphen#rollei film#rolleisuperpan200#infrared photography#infrared#chateau de Montmorin

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The death of the princesse de Lamballe

Portrait by Marie-Victoire Lemoine, dated 1779

Sold at Christie's in April 2012

On this day, 3rd September, in 1792 the Princesse de Lamballe, companion of Marie-Antoinette, was bludgeoned to death outside the La Force prison, her body stripped, her heart torn out, her head hacked off and impaled on a pike, and her pathetic remains paraded in bloody triumph through Paris over several hours. Exact details are disputed and her murder was not, of course, the only act of Revolutionary violence that September, Nonetheless the brutality of her death continues to exercise a fascination due to the contrast with her privileged aristocratic upbringing and reputation for refined sensibilities. The archetypal victim, the Princess in many ways represented a substitute for Marie-Antoinette herself.

The "myth" of the Princesse de Lamballe has recently been explored in depth by Antoine De Baecque in his Glory and Terror: seven deaths under the French Revolution (English version 2002). What follows is a modest attempt to piece together what actually happened in those final hours.

Who was the Princesse de Lamballe?

As the daughter of Prince Louis-Victor de Savoie-Carignan of the House of Savoy, Marie-Thérèse Louise de Savoie-Carignan (1749-1792) was a blue-blood of impeccable credentials. In 1767 she was splendidly married by proxy to the young Prince de Lamballe, huntsman of France and only son of the duc de Penthièvre, cousin of Louis XVI. Unfortunately the fairy-tale union was cut short by the premature death of her thoroughly debauched young husband, leaving the Princess to be presented at Court already a widow at the tender age of nineteen. Various projects for her remarriage came to naught. Financially liberated by marriage settlement - 60,000 livres, plus a life interest on further 30,000 livres - she seemed genuinely devoted to her father-in-law, who had a great reputation for piety and good works. Neither maid nor wife, she therefore continued - like Marie-Antoinette, with her unconsummated marriage - to inhabit a strange and ambivalent sexual no-man's-land. For a while she was joined in intimate friendship with the Queen - a relationship massively charged with Rousseauist emotion; Marie-Antoinette even had her friend's image painted on a mirror to make life bearable when they were briefly parted.The impression they gave was one of thoughtless insouciance. In the terrible winter of 1776, whilst people starved, the two famously fair-haired young women, twins in their bejewelled white furs, zooming through Paris on a horse-drawn sledge, the Princesse de Lamballe looking, as Madame Campan has it, like "spring clothed with ermine" or "a rose in the snow".

Alexander Roslin, Portrait of an unknown woman,

speculatively identified as the princesse de Lamballe.

In 1775 the Princess was brought to public attention for the first time, when Marie-Antoinette revived at fabulous expense for her favourite the position of superintendant of the the Queen's household, a move widely thought to be responsible for the fall of Turgot who had protested against the extravagance. Unfortunately for her future reputation, the Princess revealed herself as both a stickler for protocol and grasping for property and sinecures on behalf of her relatives (both her brothers were given senior army posts). Despite her considerable private income, she insisted on the entire salary for the post attracted and ill-advisedly offended courtiers when she as she demurred from issuing invitations to events as demeaning to her status. It was as part of a campaign orchestrated by members of the Court, that suggestions of an improper relationship between the two young women began to circulate: she became an iconic hate-figure second only to the queen herself, a milky-skinned blond ice-maiden of unshakeable hauteur and hidden perversity.

Jean-Baptiste Charpentier, The duc de Penthièvre and his daughter,

Chateau de Versailles

Ironically enough it was at this very time that the Princess was largely replaced in Marie-Antoinette's affections by the duchesse de Polignac. From the mid-1770s, she was to keep at a discreet distance, either with her father-in-law's at Sceaux or Rambouillet or in circle of the duc de Chartres, later duc d'Orléans, who was married to the duc de Penthièvre's daughter, Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon. It was this last association which prompted Louis XVI to discourage the friendship with his wife. Prompted by her brother-in-law, the Princess became involved in the fashionable new craze of freemasonry at this time and was Grand Mistress of Loge du Contrat-Social in 1780. Though later associated with radical politics, this brand of freemasonry was really little more than a pretext for balls, suppers and social events. A number of society portraits of the Princess survive from this period - small featured and fair, she is clearly recognisable by her pearls and the three feathers which characteristically adorned her luxuriant blond hair.

By Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, painted in 1782,

Château de Versailles

The accounts give a picture of a woman who was sweet-natured but protective of her privileged status, obliging to her friends and family and a little slow-witted. Straightforwardly and unimaginatively pious, she gave generously to the poor ("vos pauvres" as Marie-Antoinette remarked). In appearance she was small and fragile - even Madame de Genlis, who disliked her, admitted that she was "delicately pretty". Her best feature was the beautiful blond hair which, when it fell from beneath her cap after a bath, completely covered her face and shoulders. She was also weak in health and prone to fainting fits - though whether from a definite medical problem or an oversensitive imagination is unclear. The unkind Madame de Genlis thought the faints were a deliberate affectation - for a whole year the Princess made a point of fainting twice a week at fixed hours, her doctor conveniently at hand. We learn that she fainted in a visit to Crécy when one of the servants yawned incautiously while the party were enjoying a ghost story. It was a favourite anecdote that she even fainted at sight of a painting of a lobster.

The Princess during the Revolution

After the Diamond Necklace affair, the Princess regained some of her lost favour. As Olivier Blanc notes, her portraits from the late 1780s suggest a desire to appear more serious and reflective; thus Anton Hickel in 1788 depicts her at her desk, pen in hand:

Portrait by Anton Hickel, 1788

Liechtenstein Princely Collections

. After October 1789, following flight of Madame de Polignac and the transfer of the Court to Paris, she once again took up her duties as superintendant in charge of ceremonies, this time at the Tuileries. There are some hints that she was more actively involved than is at first sight apparent in the machinations of the captive court. Her name appears, for instance, in a list of recipients of secret payments from the Ministry for Foreign affairs. At time of the flight to Varennes she embarked from Dieppe with a passport signed by Montmorin in April 1791 and successfully reached England. If the 19th-century Secret memoirs of the Princess Lamballe are to be believed, she was involved in a whole series of manoeuvres to discover the disposition of the Pitt government. However, the careful researches of Georges Bertin suggest a more modest itinerary; the Princess was at Passy on 20th June when she heard news of the projected royal flight, went thence to Boulogne, crossed to Dover on the 23rd, took ship the next day for Ostend, and arrived at Brussels on the 27th. After the arrest of the royal family, she progressed to Aix-la-Chapelle, where she dictated her will on 15 October and then, whether by her own initiative or on Marie-Antoinette's instruction, returned courageously to Paris and her duties as superintendant.

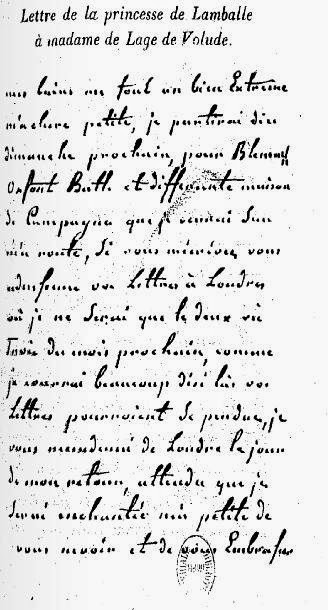

Handwriting and signature of the Princesse de Lamballe

Reproduced from Lescure, La princesse de Lamballe (1864)

Shortly afterwards the Princess was denounced by Committee of Surveillance of the Legislative Assembly and also pinpointed in the Revolutionary press for her involvement in the the secret machinations of the Court. No doubt at the very least she had some role as intermediary in the manoeuvres of the so-called "Austrian committee" and knew the identities of compromised Revolutionaries such as Sombreuil, Brissac, Valdec de Lassart, Thierry de Ville-d'Avray, through whom the Court had attempted to influence the decisions of the Revolutionary government.

By the fateful events of the 10th August, she was already singled out for vengeance.......

I

Arms of the Princesse de Lamballe,

Reproduced in Paul Fassy,

Episodes de l'histoire de

Paris sous la Terreur (1886)

References

Antoine De Baecque, Glory and Terror: seven deaths under the French Revolution (2002)

Antonia Fraser, Marie-Antoinette: the journey (2006)

Olivier Blanc, Portraits des femmes : artistes et modèles à l'époque de Marie-Antoinette (2006),p.199-206.

2 notes

·

View notes