#chicanidad

Link

From the article:

In light of recent events at the National MEChA – formerly known as Movimiento Estudiantil Chicanx de Aztlán – Conference this past weekend (March 29 to March 31, 2019) in Los Angeles, hosted by UCLA’s MEChA chapter, we come forward as a collective to write a statement. We make this statement to address the many misconceptions following the decision to permanently change MEChA’s name. During this conference we held a Resolution Circle where votes totaled to 29 in favor, three against, and two abstaining to move forward with The University of Oregon’s motion to replace “Chicanx” and “Aztlán” from the name in order to reflect our restructuring of the guiding philosophies of MEChA.

We first want to acknowledge the labor and sacrifices that Chicanxs and MEChistxs of the past had to do to get us to where we are now. We are by no means erasing those struggles; on the contrary, we are acknowledging and addressing the oppressive history and nature of MEChA. So in reality, we are honoring the history of our elders by bringing to light MEChA’s flaws and improving our organization. We are not abandoning the constructive and empowering lessons of our forerunners; we will continue the movement, work to right the wrongs of the past, and look forward to a future of liberation and radical love.

We are honoring the history of our elders by bringing to light MEChA’s flaws and improving our organization.We are not trying to take away anyone’s “Chicanx” identity. People are free to identify with the specific political and real implications of that identity. We are moving away from “Chicanx” being the sole representation of those within MECHA because it does not reflect the makeup of MEChA chapters across the US. We encourage individuals to continue to celebrate their Chicanidad within the organization, but without the exclusion of our other Latinx hermanxs who don’t identify with that. Since MEChA must be a place for Latinx people to find community in higher education, we wish to use our name to reflect that.

Furthermore, we have been disappointed and truly hurt by the disrespect shown by some members and alums, both at the Resolution Circle and on social media. This has caused divisiveness in the Chicanx and Latinx community and real harm to students. All we are asking is for us to redirect our attention to the opinions of students directly involved in MEChA who organize, campaign, educate communities, etc. After all, MEChA is a student-led movement. If we hope for unity, we must listen to those with real stakes in El Movimiento. Trust that we have rational, critical, and independent thought; we have not made this decision hastily.

The reasons for removing “Chicanx” and “Aztlán” from MEChA are as follows: Chicanx, which directly translates to Mexican-American, is exclusionary. Although some identify with the political connotations Chicanx can have, it has not traditionally been used in that way. We recognize that it would be wrong to force non-Mexican-Americans, Indigenous Mexicans who cannot identify with this term, and Black Mexicans whom this term has historically excluded to use this term to describe their political philosophy. As it is, MEChistx members who are not Mexican-American are often victims of xenophobia from Chicanx MEChistxs, and Indigenous and Black MEChistxs are often subjected to anti-Indigenous and anti-Black violence by Mestizx Chicanx MEChistxs.

Many of our ancestors were not Aztec but rather Maya, Purépecha, K’iche’, Guaraní, Garifuna, among others. As a collective, we recognize that the term Aztlán reflects MEChistxs’ appropriation of Aztec cultures and traditions; however, many of our ancestors were not Aztec but rather Maya, Purépecha, K’iche’, Guaraní, Garifuna, among others. The use of the term “Aztlán” also influences us to take part in the erasure of Indigenous peoples who are the true ancestral stewards of the US Southwest. We voted to remove “Aztlán” because although Aztlán was created as a philosophical ideology, it has had geographical consequences in claiming the land that was taken by the US on February 2, 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Chicanxs from the ’60s claimed the Southwest part of the United States as “Occupied Mexico” and our rightful land; however, this is not our land. The reality is this land belongs to the many Indigenous people who were here before the Mexicans and Chicanxs, e.g. the Diné people, the Tongva people, etc.

Continue Reading

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mañana

They look at me; then they see me. They see the tint of my skin. They see the Kahlo unibrow. They see the Cantinflas mustache. They ask: “Where are you from?” But that is not what they are asking. They are asking “Why is your skin not pale? Your facial hair so thin? Your hair so thick?” Why, why, why. And I must answer, “My mother is Mexican.” And then they ask, “Do you speak Spanish?” And I must answer, “No.” To which they ask “Why?” And I must answer. But I do not answer. I think. My mother did not teach me. Was she ashamed to be Mexican? And her child a Chicano? Perhaps she wanted me to be American, whatever that meant. But that is not enough. It has been years, I could have learned Spanish, in school or elsewhere. Mi Abuela had offered to teach me. And I declined, saying it was too much for just one summer. Is it a personal shortcoming? Am I lazy? Or destined to be monolingual? Maybe I am my mother’s child, ashamed to be myself. To be the “other” in the room. But I must answer. How long has it been? Only seconds perhaps. And I answer. “My mother did not teach me. She wanted me to be American.” And they nod in acknowledgement, understanding this familiar story. How many have lost their mother tongue of their fatherland because their mother and father wanted an American child? Different from them, same as everyone else. But that is not the case. It is never the case. We are always different. Different from our parents, from our ancestors, but also our peers, our colleagues, our compatriots. We are stuck, like a scratched record, speaking our “native” language with a broken tongue when we talk to other people of our nation. One day, things will be different. We long for that day. But we will be sure to not make the same mistakes of our forefathers and foremothers. Our children will grow up different from us, free from our struggles.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@ucla_csrc all set up for book exhibit display and selling publications at #otrócorazón2: Queering #Chicanidad in the Arts. We're in @ucla Royce 306, but main conference is in Royce 314! Come visit, bring a friend! 🤗❤✊🏽 (at UCLA Royce Hall)

0 notes

Text

Pan Dulce

In November of last year (around 11/25/17) I asked my friend Karinne in the Bay Area to send me pan dulce in the mail. At this time, my request for a sheet of copper from the Buena Vista del Cobre mine in Cananea, Sonora, Mexico had successfully been granted and the copper had arrived to me via UPS. I was curious to know how another kind of object from a different location, shipped to me in a similar way to that of the copper, would compare to the experience I had with obtaining the copper. Honestly, I didn’t feel much and I didn’t know what I wanted to do with it. So I just hid the pan dulces, each individually wrapped in their own paper bags all together in a ziploc bag, in the back of the fridge.

At first I felt a sense of guilt not having immediately “used” the pan dulces in a way I had imagined I might use them (as objects in an installation, similar to that of copper in Cobre). I felt guilty for asking my friend to go out of her way to buy the pan dulces for me and then ship them all the way to Ann Arbor only do let them mold, half forgotten, in the back of the fridge.

Periodically, I would think about the pan dulces, sitting in their silent prison, never to be eaten nor discarded, sitting in their own personal icebox limbo. And in each of these moments when I would imagine the pan dulces occupying the physical space of the bottom shelf, behind expired eggs and a bag of Granny Smith apples, I would become aware of the mental and imaginative space these sweet breads occupied within my own mind. Although I never physically interacted with the bundle of pan dulce, aside from periodically shifting it to grab another displaced food item, I became struck by my imagined interactions.

Today, 5/23/18, six months after my initial request, I was finally compelled (by some internal clock) to remove the goddam pan dulces from the fridge and photograph them. Photographing their “decay”, I was taken aback by how little mold was present (if any) on them. Instead, inhabiting each of the grease-stained paper gabs was an incredibly stale Mexican pastry crumbling profusely that inexplicably smelled like bananas. After photographing the pastries, I returned them to their spot in the back right corner of the bottom shelf—I don’t think I’m done with them yet.

Here are some of my best shots from today:

Now I’d like to take a little time to think about the “next steps” of this project, just some ramblings and ideas I have. General questions, wonderments, and curiosities of the sort.

1. Food is ephemeral, it is meant to be taken in as an energy source and eventually excreted by the body. What does it mean to “hoard” food, especially a culturally symbolic food? Am I wasting the food? What does it mean to neglect a culturally symbolic food? I expected the pan dulce to be completely decayed, however, there was hardly any evidence of mold. This to me almost speaks to a level of “endurance”, however absurd. Taking this further, this makes me think of almost an implicit “cultural endurance” that exists within people, at least within me. I can’t go on without considering this in context with the word “preservation” seeing that the bread was kept in a refrigerator, a form of technology meant to preserve food items by lowering their temperatures to a point that slows down natural decay. Had these been left out, they would have molded much quicker, I’m sure; however, there is a shit ton of sugar in pan dulce, so I can almost imagine that they would have decayed at a slower rate than a different kind of bread (not pastry).

2. I’ve become really intrigued by the mental burden the pan dulce has “imposed” on me. Every day, perhaps once or twice, almost like I am keeping tabs or an inventory, the thought of the bread crosses my mind. Each time it crosses my mind, it is shrouded by a sense of guilt as well an impulse to wait on any action. The guilt is multifaceted. First in comes from knowing that I had asked my friend for a favor and did not complete my initial intentions. However, that quickly shifted as I began to realize that “sitting” on doing anything with the pan dulce was turning into a project of its own (this). The more profound sense of guilt is the connection between the vocabulary I connect with my relationship with the pan dulce (waiting, hoarding, collecting, sitting on, pondering, contemplating, inability, hesitation, etc) and my relationship with my sense of Latinidad, Mexicaidad, Chicanidad, whichever label you wish to use. Similar to the pan dulces sitting in the back of the fridge, my relationship with my Mexican-American identity occupies a constant attention within my mentality. Much like the thoughts about the pan dulce that cross my mind daily, the thoughts, questions, anxieties I have about my own identity cross my mind several times a day, everyday. Many times, when briefly pondering the state of the pan dulce in the refrigerator, I would become consumed by questions about the “state” of my own identity. Perhaps analogous to Pavlov’s dogs (maybe that’s a stretch) the thought of the pan dulce would trigger within me an urge to “check-in” with myself and perform an audit of my perception of my own Mexican-Americanness. I am fascinated by this - and bummed that I didn’t think to take notes during each of these check-ins... aghhhhh.

3. On a final note, I will be heading back home to Santa Barbara, CA next week for my little brother’s high school graduation. The other day, when contemplating the pan dulces in the fridge, I had the urge to google how to make them. Of course, I was walking and easily distracted, so I quickly forgot my impulse. Later that day, when talking on the phone with my mother, I learned that Joey (a passionate baker) had been teaching himself how to make conchas. Putting my own urge and this news together, I am determined to learn how to make this type of pan dulce from my brother. I think it will be really cool to learn from my brother; I’ll be his apprentice.

0 notes

Text

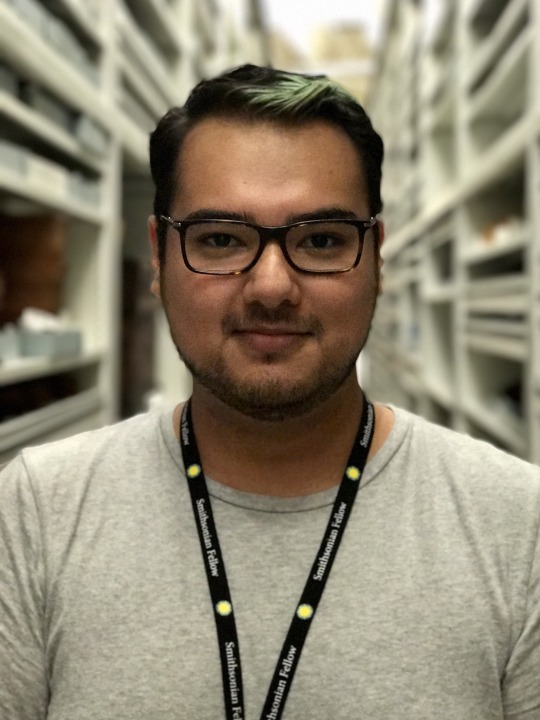

#LMSP2017 Fellow Takeover: Jonathan Cortez

Jonathan Cortez at the Cultural Resources Center branch of the National Museum of the American Indian.

¡Hola todxs!

My name is Jonathan Cortez and I am currently a doctoral student in the department of American Studies at Brown University. Thank you for joining me on my #LMSP2017 #FellowTakover blog post. Be sure to check out my #DayInTheLife by following @Smithsonian_lmsp on Instagram.

Growing up in the coastal bend region of South Texas in the town of Robstown, it is from this region’s history and proximity to the U.S.-Mexico border where I draw my inspiration for academic research and community involvement. My work focuses on the role of federally-funded labor camps along the U.S.-Mexico borderlands as a site for specific formations of race, gender, and human control during the early-to-mid twentieth century. In addition to my academic work, I find museums to be an important space to disseminate and co-create histories with communities often left out of museum narratives. Being a Latino Museum Studies Program Fellow has allowed me to hone both my research skills and my interest in museums with a focus on having a responsibility to communities.

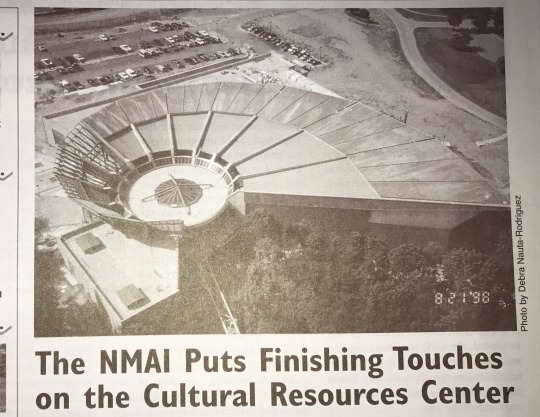

Top view of Cultural Resource Center. Photo by: Debrah Nauta-Rodriguez, from Runner No. 98-5, Sept/Oct 1998.

My practicum project is at the National Museum of the American Indian’s Cultural Resources Center (NMAI-CRC) where I am supporting Dr. Maria Martínez and Dr. Antonio Curet with the “Contextualizing Museum Archaeological Collections: The Case of Pre-Columbian Mirrors” project. Fun fact: the CRC holds most of the museum’s collections, about 98%. The NMAI views their collections as “living” in the sense that ancestral spirits continue to travel with these objects. This informs where the objects are kept, the proximity to other each other, what direction objects face, and how they are handled. By acknowledging the often violent ways in which these collections were acquired, the NMAI vows to stay in communication with Native communities and invite communities into the space to visit with their ancestral objects, and, if requested, take steps towards repatriation.

Jonathan Cortez examining the obsidian “mirror.” Photo by Maria Martínez.

My time since being at my practicum site has been a crash course in all things museums studies. Meetings about library research, archival material, data analysis, and cataloging are only a few of the training I have gone through. Curation, design, and collections will come in the next few weeks. The more special moments of the practicum thus far have been being on tours, especially with Native communities. The histories of these objects come face-to-face with their living descendants and are accompanied by many mixed emotions.

Tours with Native communities gives meaning to the collections beyond research purposes. On one tour with the Southern Ute from Colorado, the spiritual leader led a prayer in both Numic (Uto-Aztecan) and English. The CRC staff was encouraged to join the circle. The spiritual leader then prayed for the objects, acknowledging the looting and violence that took place for the museum to acquire, and he prayed for the staff, to be sure we can take care of the collection but also so that no spirits linger with us after we leave. The Southern Ute tribe proceeded to the private ceremonial room for more private prayer and smudging, if requested. As the tour journeyed through the collections, gasps at the astonishment of the objects could be heard alongside sniffles coming from a few tearful tribe members. These tours continue to bring with them emotional responses, evoking histories untold and peoples dispossessed.

Personally, this practicum continues to force me to reflect on the role of indigeneity in Latinx Studies. Traditionally indigeneity has been discussed, and rightly critiqued, within the scope of Chicanidad and the notion of mestizaje. However, working with the NMAI and getting to visit with Native communities moves past this historiographical view. Native communities are still here and continue to contribute to Latinidad as well as building their own identity within and beyond the U.S. nation-state. My time at the NMAI and CRC will continue to push me to center communities in the creation of museum design, content, and collection.

Follow the #LMSP Fellows via Instagram @smithsonian_lmsp @slc_latino, the Smithsonian Latino Center Facebook page or via Twitter @SLC_Latino.

0 notes