#china country garden crisis

Text

China's Actions Enrage the West: Why Sacrifice Our Economy?

I am deeply concerned about the actions of China that have recently sparked outrage in the Western world. As an avid observer of global affairs, I can’t help but question the motives behind these actions and reflect on the potential impact they could have on our own economy. In this blog post, I will delve into the reasons why sacrificing our economic interests for the sake of China’s agenda is a…

View On WordPress

#china country garden crisis#china deflation#china deflation crisis#china economic collapse#china economic slowdown#china economy just flipped#china evergrande#china property collapse#china property crisis#china real estate#china real estate collapse#china real estate crisis#China stimulus#economic news#economic recession#evergrande bankruptcy#evergrande crisis#global recession#investing news#recession 2024#sean foo#us dollar#world reserve currency

0 notes

Text

Inmobiliaria Country Garden se enfrenta a nuevo vencimiento de cupón en dólares

El asediado promotor inmobiliario chino Country Garden se enfrenta a otra prueba de liquidez, ya que el lunes debe pagar US$15 millones en intereses vinculados a un bono offshore, tras haber esquivado el impago en el último minuto en dos ocasiones este mes.

Country Garden, cuyos problemas financieros han empeorado las perspectivas del sector inmobiliario y han provocado una serie de medidas de…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

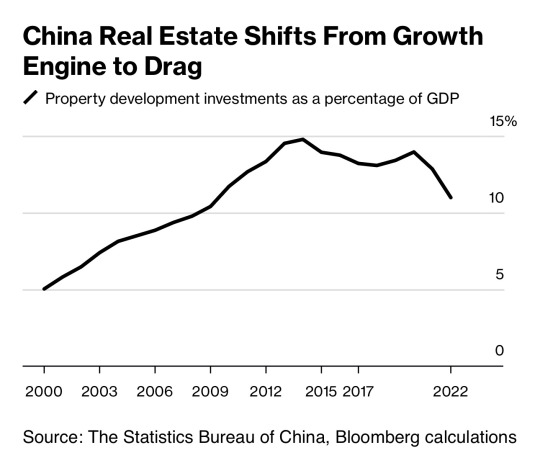

For the last three decades, the Chinese economy has resembled an impressionist painting: beautiful from afar, but a jumbled mess up close. China’s economic model has centered around investment-led growth made possible by the supply of cheap capital extracted through domestic financial repression, using a combination of policies—such as interest rate caps, capital controls, and restrictions on credit allocation directions and financial market entry—to channel capital into state-prioritized sectors. While this model has contributed to China’s rapid rise, it has also led to the entrenchment of structural issues that began to emerge well before President Xi Jinping assumed power in 2012. Instead of taking the chance for reform, though, Xi’s policies have only worsened these issues.

China faces three major structural challenges that expose it to the risk of economic stagnation akin to Japan’s “lost decades”: Escalating debt coincides with decelerating growth, sluggish household consumption lags overextended supply, and adverse demographic trends have blunted China’s edge in cheap but skilled young labor, which amplifies social welfare costs and causes housing market demand to dwindle. The inevitable reckoning of China’s structural challenges has been accelerated since Xi’s ascendence.

The fuse on this economic time bomb is steadily shortening. In recent months, critical economic indicators—from industrial profits and exports to home sales—have all recorded double-digit percentage declines. In July, while consumer prices rose globally, they fell in China, raising concerns that deflation could worsen the difficulties faced by heavily indebted Chinese companies. A convergence of idiosyncratic factors now threatens to ignite a crisis in the property and construction sector, which makes up nearly 30 percent of Chinese GDP. China Evergrande’s recently filed for bankruptcy. Coupled with the impending default of Country Garden, another major property developer, after missed bond payments this month, it has deepened the already profound sense of uncertainty and fear among the business community.

This economic uncertainty is further heightened by the Chinese Communist Party’s ever-shifting targets of anti-corruption and anti-espionage campaigns. Health care is the latest sector to fall under the gaze of authorities, even as the effects of previous campaigns against tech, private education, gaming, and finance still linger. In the background, the friction between China and the United States continues largely unabated. Private conversations among Chinese citizens, particularly the young, reveal an undercurrent of pessimism and unease. Among the contributing factors is the looming specter of military conflict with the West regarding the future of Taiwan. China’s one-child generation would shoulder the weight if such a conflict were to happen, an existential threat of unparalleled proportions.

Milton Friedman was partially correct when he famously stated that “[i]nflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” In China, the manifestation of economic deflation symptoms—even transitory—has been shaped by Xi’s departure from the reform and opening up policy and the return of expansive political, ideological, and geoeconomic aspirations reminiscent of the Mao Zedong era. We might dub the resulting phenomenon “Xi-flation,” deflation with Chinese characteristics. The cumulative policy shocks of the last five years have exacerbated, rather than quelled, the structural challenges that have been dragging—but not crashing—China’s growth.

The posture of China’s teetering-but-not-tumbling growth trajectory has long called for careful structural reform. The goal should be to squeeze out the property market bubble without bursting it, to alleviate income inequality without stifling entrepreneurship, and to foster fair competition without hurting productivity. The success of these reforms hinges on a calibrated policy orchestration. Instead, Xi’s policy has produced grandiose political rhetoric, such as “common prosperity” or “shared human destiny,” mixed with clumsy and misguided enforcement.

Economically, Xi has been a bull in a china shop. His economic policies have often shifted focus but always emphasize the party’s overarching control across nearly all dimensions of China’s economic and financial activity. Since 2017, foreign companies operating in China have organized lectures for employees to study the role of the party and Xi speeches. As of October 2022, 1,029 out of the 1,526 of the mainland-listed companies (more than two-thirds) whose shares can be traded by international investors in Hong Kong acknowledge “Xi Thought” in their corporate constitutions and have articles of association that formalize the role of an in-house party unit.

In fairness, Xi did not create China’s structural woes. However, the reform and opening up policy suffered a quiet, unheralded death as Chinese policy thinkers attempted to compensate for the absence of prudent economic strategy under Xi by ceaselessly leaping from one grand idea to the next under the banner of national rejuvenation.

For example, since December 2016, the phrase “houses are for living, not for speculation” has become the principle to curb the property sector. In 2017, the “thousand-year project” Xiong’an New Area was launched as a city of the future. In 2019, “establishing a new national system for innovation” entered the lexicon for state-led science and technology innovation. Since 2020, “common prosperity” has become the mantra behind which to launch antimonopoly and antitrust probes into China’s tech sector. And since November last year, when Xi suddenly reversed China’s zero-COVID policy, the new catchphrase has shifted to “consumption promotion.”

Xi-flationary policies have exacerbated China’s latent structural problems and rung up a steep tab. For instance, Xi’s regulatory crackdown on China’s leading tech companies wiped out more than $1 trillion in market value, a figure comparable to the GDP of the Netherlands. The zero-COVID policy incurred costs of at least 352 billion yuan ($51.6 billion) for Chinese provinces, almost twice the GDP of Iceland ($27.84 billion in 2022).

The financial cost of these policy missteps is not their worst aspect. The most profound cost of Xi-flation so far is an unprecedented run on confidence in the Chinese economy from within and without. Beijing’s old economic playbook has run out of pages when it comes to tackling this crisis. China cannot export its way out of today’s economic challenges or stimulate its way toward a full recovery without also addressing the underlying political cause. As China moves up global supply chains, foreign companies are increasingly looking for alternative countries to sources for inputs and locate production to ensure they do not fall on the wrong side of any lines drawn as part of Western policymakers’ drive to “de-risk” their reliance on China.

This is, in part, a belated reaction to the willingness of China under Xi to use economic coercion. Researchers from the International Cyber Policy Centre found that between 2020 and 2022, China resorted to economic coercion in 73 cases across 19 jurisdictions, a marked increase compared to China under Xi’s predecessors.

China’s waning comparative advantage is a long-term structural problem, but political and geopolitical factors drive the current run on confidence. As Xi continues to consolidate power, the once lucrative China premium will be further discounted due to the growing regulatory and geopolitical uncertainty. Chinese technocrats cannot fully address this run on confidence using only their limited economic toolbox, such as the People’s Bank of China’s use of the so-called precision-guided structural monetary tools to selectively provide credit for state-preferred sectors.

Xi’s global assertiveness has caused negative spillback for China’s economy. Amid China’s fraying ties with the West and multinationals hastening to diversify their supply chains, ordinary Chinese households are left to deal with mounting anxiety. They are economically less secure as a consequence of Xi’s zero-COVID policy, and they are increasingly concerned that geopolitical forces beyond their control have limited their individual futures. Xi’s commitment to reunite Taiwan with the mainland, by force if necessary, has created the perception among some in China that conflict is inevitable—the same as in the United States. This loss of confidence aggregates across hundreds of millions of Chinese households, underpinning an economic condition that James Kynge has characterized as a “psycho-political funk.”

An essential factor behind China’s economic success during the reform and opening up period was what economist John Maynard Keynes termed “animal spirits”—those emotional and psychological drivers that push people to spend, invest, and embrace risk. For decades, China not only benefited from the inflow of foreign direct investment and technology from the West, but also enjoyed a steady tailwind from the optimistic outlook of Western business leaders eager to capitalize on the globalization trend. When Western companies briefly reconsidered their involvement with China in the aftermath of the Tiananmen protests, Deng Xiaoping rescued the situation by embarking on his influential southern tour in 1992. During his tour, he the world of the party’s commitment to economic reform, stating, “It is fine to have no new ideas … as long as we do not do things to make people think we have changed the policy of reform and opening up.”

However, Xi’s policies have undone much of Deng’s legacy and upended China’s prior economic success formula. China’s appeal as a destination for both tourism and business has dimmed, and a growing number of the country’s elite look beyond the border for their future. If this trend continues, China may fall into the dreaded middle-income trap or face even graver risks such as a financial crisis. A financial crisis in China would have far greater consequences than any other previous emerging market crisis. The size of China’s economy and its level of integration dwarf that of South Korea in the late 1990s, when it was at the epicenter of the East Asian financial crisis.

The West has a genuine interest in preventing the economic downfall of China. Washington and Brussels must closely coordinate to ensure their de-risking policies send a clear message to Beijing on its intended goals and limits by drawing a bright red line around sectors with potential military dual use while clarifying in which circumstances cooperation is still encouraged. Otherwise, the West risks legitimizing Xi’s claims that economic containment is to blame for China’s economic woes, and that further self-sufficiency is the only antidote. The West must be careful to communicate that its policies are designed to avoid the global alienation of 1.4 billion Chinese people.

When the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit meets this November in San Francisco, the sister city of Shanghai, China’s economy may be on considerably less sure footing than the United States for the first time in decades. That may prove to be an opportune time for both countries to repair the world’s most consequential bilateral relationship.

The Biden administration can take a page from the playbook of Otto von Bismarck: “Diplomacy is the art of building ladders to allow people to climb down gracefully.” A good start would be for the United States to lend a ladder this fall and help China clean out its gutters—if a Xi-led China is capable of accepting the help.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Is China about to have its ‘Lehman’ moment? After Chinese property developer Evergrande filed for bankruptcy protection in the U.S., that’s been the question some have whispered. The country’s debt crisis that’s rumbled on for two years is coming to a head, with China’s shadow bank sector now defaulting on payments.

(…)

Last week, Evergrande filed for protection in the U.S. under Chapter 15 of the bankruptcy code, which helps keep creditors at bay when a company is restructuring. Evergrande’s debt is held mainly by Western investors, hence filing in Manhattan.

It’s been at the center of the Chinese property sector’s debt crisis, which first unfolded in 2021 and has reared its head again this summer. Nearly two years ago, Evergrande defaulted on making interest payments on bonds, which sparked a set of failures across the Chinese property sector.

Companies accounting for roughly 40% of China’s home sales have now defaulted on debt since the crisis first unfolded. This has led to unfinished homes and ‘ghost cities’, supply chain disruptions and institutional investors out of pocket.

(…)

It’s not the only property developer struggling this week. China’s Country Garden Holdings is looking to restructure its bond repayments totaling $535 million over three years to stave off financial trouble.

(…)

Given real estate is estimated to make up 30% of China’s GDP, there are fears the contagion in China’s real estate market could spread and create a downward spiral of the property market depressing growth.

Last week, there were rare protests in Beijing after bank subsidiary Zhongrong defaulted on several investment products without immediate plans to repay its clients. Its parent company, Zhongzhi, manages $138 billion in assets, 10% of which are exposed to the real estate market.

Moody’s has previously stated that the increased amount of defaults from property developers has raised Chinese banks’ non-performing loan rate to 4.4% by the end of last year, up from 1.9% in 2020. China’s property sector is also considered the world's largest asset class, worth around $62 trillion, so any further signs of trouble could lead to the Chinese government intervening.

(…)

As for the Hang Seng Index in Hong Kong, it’s officially entered a bear market. Around half the stocks on the index are now oversold, and it’s lost 11% of its value in August so far, which sets the scene for the Hang Seng’s worst performance since October.

The fear has spread to the U.S. markets in August, with the S&P 500 suffering three straight weeks of decline. The Nasdaq lost 5.5% in value in the same period, while the Dow Jones has seen a 3.2% decline.

Several banks have also downgraded China’s GDP growth outlook, which was previously estimated at 5% for 2023. Nomura now predicts 4.8% growth, with the likes of Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan and Barclays all following suit.”

“Country Garden Holdings Co., the distressed Chinese developer that earlier this month missed interest payments on some dollar bonds, is leaving investors in the dark about the exact date the grace period ends.

That’s adding to signs of opaqueness in the nation’s offshore junk debt market, which has lost $87 billion in the past two years.

One of China’s biggest developers, Country Garden must repay a combined $22.5 million in two coupons within the grace period, otherwise creditors could call a default that would be the developer’s first on such debt. That would threaten even worse impact than defaulted peer China Evergrande Group given Country Garden has four times as many projects.

(…)

China’s worsening property debt crisis has prompted a slew of developers including Evergrande to use grace periods in recent years. In many cases, doing so has only bought time before they eventually went on to default, adding to record debt failures.

Growing concerns that the same fate could strike Country Garden, which had 1.4 trillion yuan ($192 billion) of total liabilities at the end of last year, have dragged Chinese junk dollar bonds deeper into distress under 65 cents. The market value of Bloomberg’s index for the securities, mostly issued by builders, has shrunk to only about $44.7 billion from some $131.8 billion two years ago.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wealthy economies have high levels of production, with resource and energy use vastly exceeding sustainable boundaries, but they still fail to meet many basic human needs. This occurs because, under capitalism, the goal of production is not to improve well-being or achieve social progress, but to maximise and accumulate corporate profit. So we get plenty of SUVs, fast fashion and planned obsolescence, but chronic shortages of essential goods and services like public transit, affordable housing and universal healthcare.

Ecological economists argue that one of the best ways to deal with this problem is to establish universal public services. Public services mobilise production around human needs and well-being, and can deliver strong social outcomes with lower levels of resource and energy use. It also enables a more rapid, coordinated shift to more sustainable systems. By decommodifying and democratising key sectors such as food, mobility and housing, we can solve the cost-of-living crisis – by directly reducing prices – and help solve the climate crisis at the same time. This requires reversing the current tendency of neoliberal governments to defund and dismantle public services, which has led to the extraordinary crisis that is presently engulfing the NHS and the railways in the UK.

The cost of food has been impacted not only by the war in Ukraine, export bans by Russia and India, and Covid-related supply chain issues, but also by global heating. The entire American West, China and large parts of Europe are facing severe droughts, which has led to a number of crop failures, lower yields and higher prices. This is a long-term trend that will only accelerate if we don’t increase climate action. In 2020 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projected an increase of up to 30 per cent in the price of cereals by 2050 due to more extreme weather.

The capitalist food system is a major driver of climate change and ecological breakdown. Addressing this problem requires a general shift towards more plant-based diets, relocalisation of production where possible, less food waste, and regenerative production methods. This approach would also help to separate agriculture from the fossil fuel sector, as food production would be less reliant on fertilisers and transport, thus helping to insulate food systems from related inflationary pressures. As food price increases are also driven by financial speculation, banning this practice would contribute to stabilising prices.

In fact, a major step in addressing the cost-of-living crisis is to decommodify access to food. To do this, governments can fund regenerative farms and gardens linked to public grocery stores and community kitchens to ensure universal access to nutritious, affordable, vegetarian foods. Such a system would reduce food waste, land use and energy use, delivering significant ecological benefits while also relaxing pressure on food prices.

[...]

In fact, a major step in addressing the cost-of-living crisis is to decommodify access to food. To do this, governments can fund regenerative farms and gardens linked to public grocery stores and community kitchens to ensure universal access to nutritious, affordable, vegetarian foods. Such a system would reduce food waste, land use and energy use, delivering significant ecological benefits while also relaxing pressure on food prices.

Most global climate policy has focused on the difference between developed and developing countries, and their current and historical responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions. But a growing body of work suggests that a “polluting elite” of those on the highest incomes globally are vastly outweighing the emissions of the poor.

This has profound consequences for climate action, as it shows that people on low incomes within developed countries are contributing less to the climate crisis, while rich people in developing countries have much bigger carbon footprints than was previously acknowledged.

[...]

"Tackling global poverty will not overshoot global carbon budgets, as is often claimed. Failure to address the power and privilege of the polluter elite will. These are related because reducing carbon consumption at the top can free up carbon space to lift people out of poverty.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shimao Group Faces Liquidation Petition Amidst China's Property Sector Turmoil

(Source-constructionworld.in)

Creditors Take Legal Action

Shanghai-based real estate titan Shimao Group is the latest casualty in China’s tumultuous property market as it grapples with mounting debt and creditor pressure. On Monday, the company disclosed receiving a liquidation petition from a Chinese state-owned bank, marking another instance of creditors resorting to legal measures to recoup funds from troubled developers in the world’s second-largest economy.

Shimao Group Legal Petition and Financial Implications

According to a filing with the stock exchange, China Construction Bank (Asia) filed a “winding-up petition” against Shimao Group on April 5 in Hong Kong. The petition, citing a financial obligation of approximately HK$1,579.5 million ($204 million), underscores the deepening financial woes facing the property giant. Despite the legal action, Shimao Group has asserted its intention to vigorously oppose the petition while simultaneously striving towards an offshore restructuring aimed at maximizing value for its stakeholders.

Roots of Shimao’s Debt Woes

Shimao Group’s debt predicament traces back to July 2022, when it defaulted on interest and principal payments on a $1 billion bond. This default has precipitated a sharp decline in the company’s share value, plummeting over 14% in Hong Kong on Monday and nearly 40% year-to-date. The company’s challenges mirror those of numerous Chinese developers entangled in a crisis sparked by government measures to curb excessive borrowing, aimed at deflating the property bubble.

Impact on China’s Economy

The ripples of China’s real estate turmoil are reverberating throughout the nation’s economy. The real estate sector, once a pillar of growth, has now become a drag on broader economic recovery efforts. Lingering effects from pandemic lockdowns compounded with challenges like record-high youth unemployment and financial strains at local government levels intensify the gravity of the situation.

Evergrande’s Precedent and Ongoing Concerns

The plight of Shimao Group echoes the dramatic saga of Evergrande, the emblematic face of China’s property crisis. In a landmark decision, Evergrande was ordered to liquidate by a Hong Kong court in January. The failure to reach a debt restructuring agreement after 19 months of negotiations underscores the complexities and uncertainties surrounding the fate of investors, employees, and homebuyers entangled in the fallout.

Industry-wide Struggles

Shimao Group’s tribulations are not unique within the sector. Country Garden, another prominent developer, faced a similar fate after defaulting on its debt last year, prompting a liquidation petition from a creditor in February. As the domino effect of defaults and legal actions unfolds, the broader implications for China’s economy remain uncertain, with stakeholders anxiously awaiting resolution amidst the ongoing turmoil in the property market.

Also Read: Ripple CEO Forecasts Crypto Market to Surpass $5 Trillion

0 notes

Text

"Unveiling China's Property Crisis: The Surprising Impact on the Global Economy That You Won't Believe!"

China’s real estate industry is currently experiencing a slow and steady collapse. This can be seen in the ongoing debt crisis faced by major developers such as Evergrande and Country Garden. Additionally, the prevalence of “ghost cities” in the Chinese countryside further illustrates the dire state of the industry. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has recently lowered its global growth…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"Unveiling China's Property Crisis: The Surprising Impact on the Global Economy That You Won't Believe!"

China’s real estate industry is currently experiencing a slow and steady collapse. This can be seen in the ongoing debt crisis faced by major developers such as Evergrande and Country Garden. Additionally, the prevalence of “ghost cities” in the Chinese countryside further illustrates the dire state of the industry. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has recently lowered its global growth…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

China’s Property Crisis Is Upending Tens of Thousands of Lives

Default is all but official at one of China’s largest developers. That’s intensifying the pain for struggling homebuyers, workers and investors, just when the economy most needs a boost.

⬇️ https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-10-23/china-property-crisis-country-garden-distress-crushes-investors-homebuyers?utm_source=website&utm_medium=share&utm_campaign=twitter via @wealth

0 notes

Text

La desaceleración china y su modelo agotado hacen temblar la economía mundial

Los primeros ocho días de octubre son conocidos en China como la “semana dorada”. Cada año, el gigante asiático celebra su día nacional (el 1 de octubre) con ceremonias oficiales, desfiles y eventos que impulsan desplazamientos masivos y la llegada de turistas internacionales.

Este año sirvió de termómetro para poner a prueba la recuperación del dragón rojo… y ha asustado a los mercados: en esta ocasión la economía no brilló. Si bien los datos oficiales señalan un repunte del consumo superior a 2019, este sigue siendo insuficiente para impulsar el nivel de crecimiento al que China está acostumbrada.

Las grietas en la economía del gigante asiático han suscitado el temor global entre los inversores. La crisis de Evergrande, la principal empresa inmobiliaria del país, así como los problemas de liquidez del banco en la sombra, que carece de la supervisión y de los controles propios de los bancos, han hecho tambalear la seguridad de los inversores, que se ilusionaron demasiado pronto por una florida recuperación de la economía china. Además, la estricta intervención del régimen de Xi Jinping y la ausencia de un banco central independiente siguen generando dudas sobre el verdadero estado de salud del gigante chino.

Por ello, los inversores siguen atentos a su economía. Según los datos publicados el pasado 13 de octubre, las exportaciones cayeron un 6,2% en tasa interanual en septiembre (frente al 8% esperado por los analistas) y las importaciones también disminuyeron un 6,2% el mismo mes. Pese a quedarse en terreno negativo, ambos indicadores señalan una moderación de las caídas respecto al verano. La inflación, en cambio, no se inmutó. En septiembre se quedó en el 0% en tasa interanual (frente al 0,2% esperado), mientras la subyacente aumentó un 0,8%. Si tuvieran que dar un nombre a este escenario, los analistas consultados coinciden en uno: desaceleración.

Este sumidero de problemas es síntoma de que el modelo de crecimiento de China, basado en las exportaciones y en la acumulación de capital, está agotado. Michael Pettis, miembro de la Fundación Carnegie y experto de China, explica que desde 1980 el gigante asiático implementó un modelo de desarrollo basado en la inversión, especialmente en vivienda e infraestructuras, y altos ahorros. Si bien fue exitoso hace tres décadas, los problemas empezaron a aflorar hace unos 10-15 años. “China aumentó tanto el nivel de inversión que la economía ya no podía absorberla productivamente. Desde entonces, como hemos visto en otros países, su crecimiento se impulsó mediante un incremento la deuda”, explica. Scope Ratings estima que la deuda pública china alcanzará el 147% del PIB en 2027.

En los últimos años los mandatarios intentaron alejarse de este modelo, hacia uno centrado en el consumo. Sin embargo, la pandemia supuso un frenazo en su intento. La exportaciones habían sido una fuente clave de crecimiento para la nación durante la crisis del coronavirus, pero el enfriamiento de la demanda mundial mermó la recuperación de China y las expectativas de los mercados. Sin embargo, para Luis Pinheiro, economista de CaixaBank Research, la cota de China a nivel global está llegando a su límite, especialmente por las tensiones geopolíticas con EE UU y la eurozona, y ya no pueden ser el principal motor de crecimiento. Del otro lado, la extraordinaria dependencia de China en inversiones en propiedades e infraestructuras supone, a día de hoy, el mayor reto.

El sector pesa en torno al 15% sobre el PIB chino, pero de forma indirecta aporta más de un 30%. Además, supone un 20% del empleo urbano y ha sido el instrumento de inversión más importante entre la población, ya que representa en torno al 70% de los activos totales de los hogares, según Mali Chivakul, economista de mercados emergentes en J. Safra Sarasin Sustainable AM. Pero la crisis de Evergrande, y de la más reciente Country Garden, reveló los límites de un sector que se ha convertido en un quebradero de cabeza.

Cuando Evergrande, que fue la principal empresa inmobiliaria del país, entró en default en 2021 empezó a revelar las primeras grietas del sector. El gobierno en aquel entonces endureció el acceso a la financiación bancaria a las promotoras con un alto nivel de deuda, bajo el lema del gobierno de Xi Jinping “la vivienda es para vivir en ella, no para especular”. El pasado agosto Evergrande se declaró en quiebra de forma oficial en EE UU, para evitar el embargo de sus activos.

A esta, se suma Country Garden, la principal promotora del país, que a finales de agosto anunció pérdidas de más de 6.000 millones de euros en el primer semestre de 2023. No se trata de casos aislados. Según Bloomberg, de las 38 promotoras inmobiliarias estatales que están registradas en Hong Kong y en China continental, 18 han anunciado pérdidas en la primera mitad del año.

Por otro lado, los expertos debaten todavía sobre las consecuencias de la crisis del sector inmobiliario. Los más optimistas la consideran una “crisis local” con un impacto directo moderado en los mercados. Pese a ser la segunda economía global, China no tiene una conexión muy estrecha con los mercados financieros globales a diferencia, por ejemplo, de EE UU. “Se estima que los inversores chinos detengan un 5% de activos y pasivos globales, un nivel muy lejano al tamaño de su economía”, explica Luis Pinheiro.

Asimismo, el economista recuerda que la crisis de Evergrande es un viejo conocido y todavía no ha creado fuertes turbulencias en los mercados. “El mercado de bonos internacionales en China, en particular en el sector de la construcción y de las inmobiliarias, ya está descontando una probabilidad muy elevada de este default en gran parte de las promotoras”, explica.

El contagio internacional no debe preocupar, ya que el escenario actual es muy diferente al que se vivió durante la crisis financiera de 2010. En ese entonces, en España los bancos financiaban las hipotecas emitiendo deuda en el exterior y se encontraron de repente sin liquidez por la falta de confianza de los inversores. En China, en cambio, la financiación del sector inmobiliario viene de las familias, de unos bancos y de la emisión de deuda pero no se trata de financiación externa, según explica Alicia Herrero, economista jefe de Asia-Pacífico de Natixis. “La caída de oferta de la vivienda es más lenta que en España, porque mientras aquí nadie podía financiar un solo proyecto, en China las promotoras del Estado compran el terreno y tienen liquidez”, destaca.

Pettis también descarta una crisis financiera en China. Es más, considera que se enfrentará a un “ajuste lento y prolongado” como el que vivió Japón después de 1990, con un impacto limitado en los mercados pero desigual. “Los países y sectores que se beneficiaron de los altos niveles de inversión en China, como los productores de bienes de capital o materias primas industriales, se verán gravemente afectados por la brusca caída de la inversión, mientras que los que se beneficiaron del consumo chino, como los productores de bienes de consumo y materias primas agrícolas, se desempeñarán bien”, concluye.

No obstante, no faltan los pesimistas que consideran que el estallido de la burbuja podría escalar. Virginia Pérez, directora de inversiones de Tressis, cree que la quiebra de Evergrande podría contagiar el sector y causar problemas financieros en la industria. Además, generaría una mayor aversión al riesgo y una pérdida de confianza en los mercados.

Los ojos de los inversores miran fijamente a los próximos datos macroeconómicos de China como el PIB, que se conocerá el miércoles, y que sugerirá si el dragón rojo va camino de convertirse en un cisne negro.

Los inversores esperaban con expectación el abandono de la política Covid cero en China y la recuperación de los viajes internacionales. Sin embargo, el impulso del gigante asiático no se ha visto. Ante unos datos que apuntan a una desaceleración de la economía, los analistas señalan la posibilidad de una japonización del dragón rojo, que supondría un periodo de bajo crecimiento y tipos de interés deprimidos, como ocurrió en Japón en los años 90. Vladimir Oleinikov, analista senior de CFA, y Christoph Siepmann, economista de Generali Investments identifican las similitudes.

Mercado inmobiliario. La contracción del nivel de inversión inmobiliaria, de venta de propiedades y de los precios de la vivienda se han contraído notablemente, tal y como ocurrió en Japón. Sin embargo, la morosidad estimada en el sector parece hasta ahora más asumible para los bancos y el gobierno chino ejerce un control mucho mayor sobre los precios, los promotores, los bancos y sobre las necesidades de desapalancamiento.

Inflación. En julio el IPC de China cayó un 0,3%. Si bien repuntó en agosto un 0,1%, en septiembre se quedó inmutada en el 0%. Los analistas interpretaron estos datos como un sintoma de un problem de deflación de larga duración, como el que protagonizó Japón en las últimas décadas.

Demografía. La proporción de personas mayores de 65 años era del 12,7% en Japón en 1991, similar a la de China en la actualidad. Tal y como el país nipón, China se enfrenta a una rápida disminución de su población en edad de trabajar y, por lo tanto, a una caída de la productividad de la economía.

Deuda/Pib. El ratio deuda/Pib del sector privado no financiero de China ha alcanzado el 220% del Pib a finales de 2022, y supera el de Japón de 1990, que llegó al 202% del Pib.

0 notes

Text

Evergrande's Implosion: Debunking China's Impending Collapse

In this blog post, the focus will be on debunking China’s impending collapse through the lens of Evergrande’s implosion. The author delves into the factors contributing to the current situation, exploring the potential consequences and offering insights into the overall stability of the Chinese economy. By examining the challenges faced by one of China’s prominent real estate giants, this article…

View On WordPress

#china#china country garden#china dumps treasuries#china dumps us bonds#china economic crisis#china economy#china economy collapse#china economy just flipped#china evergrande#china real estate#china real estate crash#china real estate crisis#china us dollar#country garden crisis#economic news#evergrande bankruptcy#evergrande crisis#evergrande implosion#financial crisis#global recession#investing news#recession 2024#sean foo#world reserve currency

0 notes

Text

Chinese property sector crisis

Hui Ka Yan, who grew up poor in the countryside, was a symbol of China’s economic rise. With Evergrande teetering, his future is uncertain, too.

Country Garden’s (2007.HK) entire offshore debt will be deemed to be in default if China’s largest private property developer fails to make a $15 million coupon payment on Tuesday, the end of a 30-day grace period. Non-payment of this tranche is set to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Unveiling the Enigmatic Eclipse: China's Country Garden on the Brink

Evergrande, China’s leading private property developer, is currently facing severe financial challenges that have raised concerns about the stability of the country’s housing market. While these troubles may not directly trigger a widespread Chinese debt crisis, they have the potential to weaken Beijing’s efforts to stabilize the housing sector.

The ongoing financial troubles of Evergrande have…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: Country Garden Caves to Debts as China’s Real Estate Crisis Worsens by Daisuke Wakabayashi

By Daisuke Wakabayashi

The property giant was unable to repay a loan and signaled it would default on its debt, becoming one of the biggest casualties of China’s deepening property crisis.

Published: October 10, 2023 at 12:09AM

from NYT Business https://ift.tt/KUYVBhS

via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

[ad_1] Fresh drama at property developers including China Evergrande Group is jeopardizing President Xi Jinping’s latest efforts to end the housing crisis. Just as China enters a key holiday sales season, a raft of headlines are weighing on already-frail confidence in the property market. Evergrande said it has to revisit its debt restructuring plan and a unit missed a yuan bond payment. Former executives at the defaulted real estate giant have been detained, Caixin reported. Meanwhile, China Oceanwide Holdings Ltd said it is facing liquidation and Country Garden Holdings Co is still trying to avoid a potential default. The news, which contrasts with a slew of recent government measures to prop up housing demand, has fueled investor confusion over whether authorities have a unified plan to stabilize the market. It couldn’t come at worse time for Chinese developers counting on the upcoming Golden Week holiday period to spark a long-awaited revival in home sales.“Any setback in the process will negatively affect the still very fragile market sentiment of almost all players in the sector and defeat the policy purpose,” said Zhi Wei Feng, a senior analyst at Loomis Sayles Investments Asia Pte.A Bloomberg Intelligence gauge of Chinese developer shares fell 0.7% on Tuesday morning, a day after dropping the most this year as the crisis at Evergrande entered a new phase. The developer scrapped key creditor meetings and said it must rethink its debt overhaul plan, raising the risk of a liquidation of the nation’s most indebted builder. On top of that, Caixin reported that Xia Haijun, an ex-chief executive officer of Evergrande, and Pan Darong, a former chief financial officer, have been detained by Chinese authorities.The eight-day national holiday starting Friday is the centerpoint of the industry’s September-October busy season. The stakes are higher than ever this year, as the housing slowdown weighs on China’s economic recovery and developers that are struggling to refinance rely on cash from sales to meet debt obligations. “Property sales this year have been very lackluster, so for most developers accelerating transactions in the two months will be especially crucial,” said Zhang Hongwei, founder of Jingjian Consulting, which advises real estate companies. If sales aren’t good enough by October, local governments will roll out more stimulus, Zhang added. An easing of mortgage restrictions at the end of August triggered a spurt of home sales in larger cities that is already losing momentum. That’s prompting speculation policy makers will need to do more to revive sentiment which has been hammered by worries over unfinished apartments, falling property values, high unemployment and dwindling incomes. Some builders are already taking aggressive steps to entice homebuyers. One developer in Guangdong is offering incentives to buyers of its Royal Skyrim apartments in Shenzhen to purchase additional properties elsewhere in the province. They can enjoy down payments of as low as 20% at its project in smaller Dongguan city nearby, according to agents. Thirteen developers from Harbin, the capital of China’s northernmost province, went to the eastern city of Nanjing to promote their 21 projects earlier this month, hoping that buyers fond of traveling would consider them as holiday residences. Local authorities are helping out, too. A city government in central Anhui province gave out 5,000 spending vouchers of as much as $137 each to homebuyers, according to an official announcement. To seize the sales window, local authorities have been following each other to stimulate housing demand in recent weeks. Some have loosened rules banning non-residents from purchasing property there. Guangzhou made such a move in some urban areas last week, marking one of the most significant steps taken in a tier-1 city. Beijing and Shanghai still restrict non-locals from buying property and place limits on how many units each household can own. “Whether tier-1 cities will step up loosening depends on how much their housing markets recover,” said Chen Wenjing, associate research director at China Index Holdings. “The Guangzhou move signals that it’s not impossible anymore.” Potential policies include making more people eligible for purchases in suburban areas, where sales are usually more lackluster. Homebuyers are also watching whether Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen will reduce their minimum mortgage rates for first homes to lower floors guided by the central bank earlier this month.Still, there are entrenched barriers to a recovery that such measures can’t easily overcome. As well as the tough job market, China’s aging population and an oversupply of housing limit the upside for investing in real estate.Former People’s Bank of China policy maker Li Daokui said a recovery may take as long as a year and Beijing should do more to encourage lending to cash-strapped developers. Officials are treading a fine line on how far to push stimulus. While a persistent real estate slump poses risks to the government’s growth target of 5% this year, it wants to reduce the economy’s reliance on a leverage-driven property market in the long run. For now, the expectation that home values will keep falling is among the biggest factors deterring buyers. Home prices dropped the most in 10 months in August, led by declines in smaller cities. “Expectations on housing prices have gradually stabilized, but the outlook on most tier-2 cities and smaller cities is still negative,” said Chen at China Index. “For most cities in China, the home market needs to take more time to recover.”What Bloomberg intelligence says: New-home inventories, at over decade-highs in tier-2 and -3 cities, suggest pricing pressure is likely to stay, while surging listings of existing homes indicate heavy supply in that market.—Kristy Hung, BI real estate analyst !(function(f, b, e, v, n, t, s) function loadFBEvents(isFBCampaignActive) if (!isFBCampaignActive) return; (function(f, b, e, v, n, t, s) if (f.fbq) return; n = f.fbq = function() n.callMethod ? n.callMethod(...arguments) : n.queue.push(arguments); ; if (!f._fbq) f._fbq = n; n.push = n; n.loaded = !0; n.version = '2.0'; n.queue = []; t = b.createElement(e); t.async = !0; t.defer = !0; t.src = v; s = b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t, s); )(f, b, e, ' n, t, s); fbq('init', '593671331875494'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); ; function loadGtagEvents(isGoogleCampaignActive) if (!isGoogleCampaignActive) return; var id = document.getElementById('toi-plus-google-campaign'); if (id) return; (function(f, b, e, v, n, t, s) t = b.createElement(e); t.async = !0; t.defer = !0; t.src = v; t.id = 'toi-plus-google-campaign'; s = b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t, s); )(f, b, e, ' n, t, s); ; window.TimesApps = window.TimesApps )( window, document, 'script', ); [ad_2]

0 notes