#evan mandery

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Time Travel - Soul Forge Podcast 296

New Post has been published on http://esonetwork.com/time-travel/

Time Travel - Soul Forge Podcast 296

Time travel is a fun concept to contemplate. When would you go? How would you get there? The questions and thought experiments are endless. There might not be a more exciting concept in all of pop culture.

Time travel is the hypothetical activity of traveling into the past or future. Time travel is a widely recognized concept in philosophy and fiction, particularly science fiction. In fiction, chrono travel is typically achieved through the use of a hypothetical device known as a time machine. The idea of a time machine was popularized by H. G. Wells‘ 1895 novel The Time Machine.

Speaking of travel through time, this episode travels back 9 years. At that time, I was recording the Rusted Robot Podcast with my wife. Episode 32 was all about traveling through time. On this episode, we will all travel into the past to hear that episode that was recorded so long ago.

The bulk of the show references a T-shirt I once owned. On this shirt was a clock and each hour was a different method of pop culture time travel shenanigans. Some travel methods include the T.A.R.D.I.S. from Doctor Who, the time machine from the classic film The Time Machine, and the Delorean from the Back to the Future franchise. Also included is the Guardian of Forever from the classic Star Trek episode, “The City of the Edge of Forever”. This leads into a nice discussion of Star Trek.

Later in the episode, we talk about books that include temporal displacement. Stephen King wrote 11/22/63 and Evan Mandery wrote a book called Q. The episode finishes up with a talk about some Doctor Who collectibles.

This week’s podcast promos: Cigar Nerds Podcast, and The Con Guy

#Back To The Future#Bill and Ted#DeLorean#Doctor Who#ESO#Geek#geek podcast#Geek Talk#Harry Potter#nerd podcast#prince of persia#Soul Forge#Star Trek#TARDIS#Terminator#Time Machine

0 notes

Text

Politics: The Supreme Court Is Set to Kill Affirmative Action. Just Not for Rich White Kids. — The Dirty Secrets of Elite College Admissions.

— Evan Mandery | October 31, 2022 |

When He Was 8 Years Old, Michael Wang decided he wanted to go to Harvard. “I don’t know if it’s the Asian stereotype,” he told me, “but I saw it as an avenue to social mobility.” Though he wouldn’t have thought of it in these terms when he was 8, Michael meant the sort of upper-echelon mobility familiar to graduates of elite colleges. Specifically, he wanted to be a neurosurgeon. Because he was that sort of kid, he read several peer-reviewed articles about cloning and checked the authors’ credentials. When he saw that many of the researchers had gone to Harvard, he knew that was the college for him.

From that point forward, Michael’s parents made it their life’s work to help their only child achieve his goal. Michael’s dad—who goes by Jeff—had a sense of what it would take. He’d come to the United States from Shanghai in the 1980s as part of the wave of Chinese students who had emigrated to the West when Deng Xiaoping implemented the Four Modernizations following Mao Zedong’s death. Jeff got a PhD in physics from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, worked in banking for a while, and then transitioned to tutoring students in math and science. Today he runs a Mathnasium franchise in Union City, California, where Michael grew up. Many of his students went on to top colleges, and Jeff watched and emulated the parents’ tactics. Sociologist Annette Lareau would call it “concerted cultivation.” Yale Law professor Amy Chua might say that he became a Tiger Dad.

This is an adapted excerpt from Poison Ivy: How Elite Colleges Divide Us, published October 25, 2022, by The New Press. Copyright © 2022 by Evan Mandery. Photo by Ilona Lieberman

In fifth grade, Jeff persuaded the school district to let Michael take algebra. Each day, he picked his son up at his elementary school and drove him to the middle school for his advanced math class. In seventh grade, he collected Michael at the middle school and drove him to a local high school to take Algebra II. By his sophomore year, Michael had finished BC Calculus. He ended up taking 15 AP courses. Michael’s 4.64 GPA made him salutatorian of his class. He got a perfect score on the ACT and nearly aced the SAT, too, with scores that put him squarely in the 99th percentile. He also played piano, debated at a high level, and founded a math club. In the fall of 2012, Michael sent off his college applications—about 25 in all—with optimism and the satisfaction of knowing he’d done everything within his power to increase his chances of getting into a top college.

To say he was disappointed by the replies would be a vast understatement. By any ordinary standard, Michael did quite well, and he’s soberer about the experience in retrospect, but at the time he felt devastated. Yale said no. Princeton said no. Stanford said no. Harvard put him on the waitlist. Then it said no. Columbia did the same thing. He wasn’t consoled by Berkeley’s offer of a free ride or by Penn and Georgetown’s offers of half scholarships. “I was definitely disappointed receiving that many rejections,” Michael told me when I spoke with him for my new book, Poison Ivy: How Elite Colleges Divide Us, from which this essay is adapted. “I thought to myself, ‘What more can I do at this point?’ ” He decided to go to Williams, which offered to cover 90 percent of his tuition.

If Michael Wang’s story ended here, it’d be typical of high achievers in the modern era, in which acceptance rates at the Ivies and other elite schools hover around 5 percent. At this point, though, Michael did something decidedly atypical: He wrote the colleges asking why he’d been rejected and suggested that he’d been the victim of discrimination. Ten years later, he still has their replies. Yale’s dean of undergraduate admissions wrote that the college believed that its policies “do not disadvantage Asian American students relative to majority white students in a holistic admissions review, and also that we are in compliance with all relevant legal requirements.”

Not surprisingly, Yale’s letter didn’t make Michael feel much better. He obsessed about the matter. During summer vacation, he read US Supreme Court decisions on affirmative action and The Chosen, Berkeley sociologist Jerome Karabel’s definitive history of college admissions at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Karabel recounted how Jews had accounted for more than 20 percent of Harvard freshmen in the 1920s until Harvard’s president, A. Lawrence Lowell, warned that the “Jewish invasion” would “ruin the college” and proposed to cap their numbers at 15 percent. An expository writing teacher at Harvard argued in a New York Times op-ed that Asians had become the new Jews. More than half of Harvard applicants with exceptionally high SAT scores were Asian American, he wrote, yet they made up less than 20 percent of admitted students. And while Asians were the fastest-growing racial group in the United States, their numbers at Harvard hadn’t increased in decades.

In June 2013, Michael filed a complaint with the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. “As recipients of federal funding,” he wrote, “these private universities cannot discriminate on the basis of race, sex, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, etc. Yet, they all resort to race-conscious admissions practices that violate existing federal laws and infringe upon my rights guaranteed by the Constitution.” The universities, he said, were guilty of race-norming—meaning they were evaluating test scores and other metrics differently depending on the race or ethnicity of the applicant. Though Michael asked for his admissions decisions to be reconsidered without reference to race, he understood there was almost no chance of this happening. “My concern was helping out high school friends who were juniors,” he says. “These policies affect a lot of people.”

Investigators from three different offices of the Department of Education reached out to Michael. A lawyer in the department’s Boston office told him that they’d been investigating Harvard since the 1990s, but as Michael puts it, they didn’t have a smoking gun. He did what he could to advance the cause. In July 2014, he wrote an op-ed in the Mercury News against SCA-5, a bill that would have reinstated affirmative action in California, where it had been illegal since 1996. SCA-5 went down.

By this time, Michael had caught the eye of Ed Blum. Blum is the only person I’ve ever heard of whose Wikipedia title is “litigant.” He was the architect of Shelby County v. Holder, the 2013 Supreme Court decision that eviscerated the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and Fisher v. University of Texas, a 2016 decision that, but for Antonin Scalia’s untimely death, would have gutted affirmative action. Blum called Michael at Williams, said that he was gathering potential plaintiffs for a lawsuit against Harvard, and asked whether Michael would be willing to serve as their spokesperson.

Michael said yes.

Students For Fair Admissions v. Harvard is the most significant challenge to affirmative action in a generation. The court heard oral arguments in the Harvard case and a related University of North Carolina case on October 31. Based on skeptical questioning by the conservative justices about the meaning and value of campus diversity, among other matters, it is widely expected that they will rule to end affirmative action as we’ve known it for the past half-century. “Harvard does not discriminate,” Lawrence S. Bacow, the school’s president, insisted in a statement after the Supreme Court first announced it would take the case. “[O]ur practices are consistent with Supreme Court precedent; there is no persuasive, credible evidence warranting a different outcome.”

But though it may seem paradoxical, it’s important to understand that this construction is in large part Harvard’s own doing, the consequence of its stubborn insistence—which all elite schools share—on preserving the status quo in US college admissions, almost every aspect of which is slanted in favor of kids from wealthy, overwhelmingly white, families. If nothing else, SFFA v. Harvard demonstrated this conclusively through discovery—the pretrial production of documents and deposition testimony—which opened the first significant window into Harvard’s previously opaque admissions process.

Throughout that process, officers are allowed to give “tips”—extra points—to applicants for “distinguishing excellences.” These include capacity for leadership, creative ability, and geography. They also include economics, race, and ethnicity. This speaks directly to a 1978 Supreme Court decision, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, which held that racial quotas are unconstitutional, but that race could be considered as a “plus” factor. If the high court now eliminates racial preferences, any college inclined to do so could still diversify along socioeconomic or geographic lines. But as we will see, those paths require upsetting the status quo to surrender some of the advantage afforded to wealthy applicants. And it’s hard to be too optimistic about the prospect of elite schools doing so after seeing how Harvard makes its high-end sausage.

Harvard divides applications into geographic dockets based on high school location. Each is initially reviewed by an admissions officer assigned to that docket, who rates the applicant based on academics; extracurriculars; athletics; personal qualities such as integrity, helpfulness, courage, kindness, empathy, self-confidence, maturity, and grit—and school support, which basically means the strength of the applicant’s recommendations. This “first reader” also gives a summary rating. The vast majority of students also sign up for an interview with one of 15,000 alumni interviewers, who separately scores the applicant on the same categories. The scores range from one to six, with one being the highest. Very few applicants score worse than a four. It’s the admissions version of grade inflation.

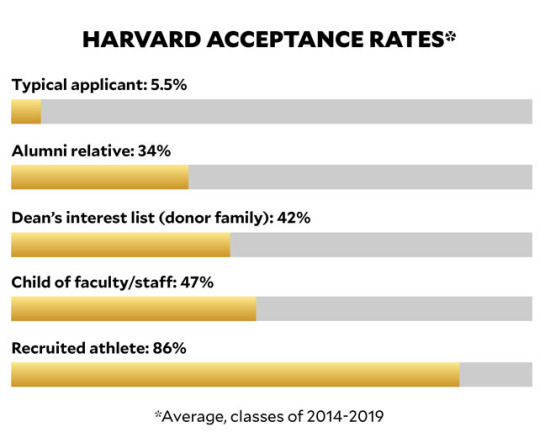

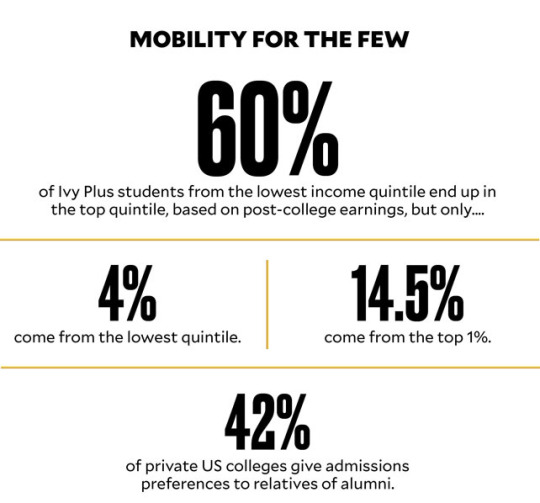

Like most elite colleges, Harvard also gives explicit preferences to applicants known in the world of higher education as ALDCs, a group that includes recruited athletes as well as the children of faculty, donors, and alumni—the alumni kids are called “legacies.” ALDCs, approximately half of them legacies, represent about 30 percent of every Harvard class, and about 43 percent of the college’s white students. Being a member of this rarefied group improves one’s chances of getting in by an order of magnitude. The admit rate for typical applicants to Harvard’s Classes of 2014-19 averaged 5.5 percent, according to data produced in SFFA v. Harvard, but the college accepted nearly 34 percent of legacy applicants, 47 percent of faculty kids, and 86 percent of recruited athletes.

Back in 2004, a team of Princeton researchers determined—based on data from three elite schools that offer admissions preferences to athletes, legacies, and underrepresented minority applicants—that being a legacy effectively gave applicants a boost equivalent to scoring 160 additional points out of 1600 on the SAT, even though legacies tend to do slightly worse in college than nonlegacies. (By comparison, Black applicants received the equivalent of a 230-point boost, Hispanic applicants 180 points, and athletes 200 points. Asian applicants suffered the equivalent of a 50-point loss.)

SFFA’s legal claim is simple: The plaintiffs say Harvard’s subjective admissions factors are stacked against them. Because so much of the class is set aside for ALDCs, and Asian Americans aren’t regarded as a disadvantaged minority, the competition they face is brutal. The plaintiffs presented most of their statistical case through Peter Arcidiacono, an econometrician based at Duke. Arcidiacono testified that if Harvard relied solely on academics, Asian Americans would constitute more than half of its admitted students, as opposed to the current 20 percent. Race might be a plus factor for others, but for Asians it’s a big minus.

Arcidiacono is an expert witness for the plaintiffs, so if you’re skeptical of his framing, consider this evidence from New York City. By state law, the sole criterion for admission to the city’s eight specialized high schools is (for now) performance on the Specialized High School Admissions Test, or SHSAT. These eight schools include Brooklyn Tech, where my dad was principal; Bronx High School of Science, where my wife went; and Stuyvesant, which has the highest cutoff. In 2020, Asians filled 524 of the 766 available slots at Stuyvesant—68 percent. It’s fair to question, as many have, whether the SHSAT, like the SAT, is simply another instrument correlated with wealth, or whether any single factor should decide someone’s fate, but it’s powerful evidence that Arcidiacono’s claim has merit.

What held Asian American applicants back, Arcidiacono found, were their personal ratings. Admissions officers gave ones or twos (on the aforementioned six-point scale) to a smaller share of those applicants than they did to students from any other racial or ethnic group. An investigation of Harvard by the Department of Justice during the 1990s found a similar pattern. Asian applicants were presumed to be oriented solely toward math and science. They were routinely described as bland, flat, or unexciting—to quote one reviewer: “He’s quiet and, of course, wants to be a doctor.” Of all the factors Arcidiacono identified, nothing was quite so damning as to be labeled “standard strong.” In a sample of 10 percent of the applicants to Harvard’s class of 2018, 256 students were labeled this way, and 114 of them were Asian American.

None got in.

Seven Months After SFFA filed its lawsuit, a company named Ivy Coach mocked Michael Wang on its blog. Ivy Coach is one of the many private consulting firms that guide parents through the process of getting their kids into elite colleges and boarding schools. After CNBC reported that Ivy Coach charged more than $100,000 for its services, the company boasted on its blog that the news station had “grossly underreported” its fees. When the New York Post reported that the company charged one mom $1.5 million, Ivy Coach didn’t deny it, but rather wrote that the company makes “absolutely no apologies” for what it charges. For the 2020-21 school year, more than 43 percent of incoming Harvard freshmen from families making more than $250,000 a year reported using private admissions counselors like Ivy Coach.

Ivy Coach claimed that Michael had made a fundamental error in how he marketed himself. In emphasizing his piano ability and debating skills, he’d presented himself as well-rounded “when that is the precise opposite of what schools like Yale, Princeton, and Stanford seek.” If only Michael had been reading the company’s blog, he’d have known to make himself “extraordinary at one thing” as opposed to “ordinary at lots of things.”As Ivy Coach explained in another post, “Ordinary’s boring. Extraordinary’s anything but boring. Highly selective colleges don’t want boring. They want extraordinary. Understood? We hope so.”

Jon Han

In Michael’s defense, Harvard’s own data contradicts this advice. To make its statistical case, Harvard called on David Card, a Berkeley economics professor. Card argued that strength across multiple dimensions mattered enormously. He found that only 12 percent of admitted students were “one-dimensional stars,” meaning that they got a rating of one in a sole area, but scored two or better in fewer than three categories. By contrast, 46 percent of admitted students were “multi-dimensionally excellent,” meaning they got a score of at least two in three or more categories. Another 31 percent were “multi-dimensionally solid.”

In the context of the lawsuit, Card’s argument was that Asian applicants tended to be one-dimensional academic stars whereas white applicants tended to have better nonacademic ratings and were generally more multidimensionally excellent or solid. So Michael could be forgiven for not understanding that investing another few thousand hours into his piano practice to further cultivate his most distinguishing excellence risked branding himself as a one-dimensional star.

We may not know what a distinguishing excellence is, but we certainly know what it’s not. It’s not working at Taco Bell or Burger King. Jobs only came up twice in Card’s report—each time to say that Arcidiacono hadn’t considered them, but never to say how much weight Harvard attached to them. That’s because Harvard doesn’t attach any explicit weight to jobs. If the college gives a tip to a socioeconomically disadvantaged student, it is in spite of their disadvantage, not because of it. No one views working a near-full-time job—as almost all my City University of New York students do—as a virtue that should count toward acceptance.

SFFA’s case is complicated by a simple truth: It’s probably not Harvard’s direct aim to disadvantage Asian applicants. Harvard’s admissions office is reasonably diverse, and during the trial several of the officers adamantly denied any animus or conscious prejudice. When one Asian-American admissions officer was asked her reaction to the allegations at trial, she said, “It’s not what I know our office to be. It’s not who I am. I would never be part of a process that would discriminate against anyone, let alone people that looked like me, like my family, like my friends, like my daughter.”

US District Court Judge Allison Burroughs credited the staffer’s testimony in ruling for Harvard, and she was probably right to do so, though it’s easy to be skeptical given the Ivy League’s historical transgressions. James Conant, who served as Harvard’s president from 1933 to 1953, was part of an admissions committee that suggested using letters of recommendation and interviews to assess “aptitude and character” as a way of addressing the so-called Jewish problem—too many Jewish kids qualifying for coveted Ivy acceptances. The notion of the Yale man—of “sound physique” and “grace of body”—evolved to combat what was known in New Haven as the “Hebrew invasion.” So, too, Princeton’s commitment to educating “leaders,” not “bookworms.”

In the years since, elite colleges have made undeniable strides in improving the racial diversity of their classes—even if, almost certainly, it’s also true that Asians have been disadvantaged by some of the policies that have promoted these broader gains and that diversity gains overall have been limited by universities’ steadfast commitment to preserving ALDC tips.

If SFFA v. Harvard were about socioeconomic status rather than race, there could be no doubt as to Harvard’s intent. Every experience valued by elite colleges is directly correlated with wealth. The experiences that allow young people to “distinguish” themselves are not uniformly available—not by a long shot. About 90 percent of students from families in the top US income quartile participate in school-based extracurriculars, whereas only 65 percent of students from the lowest quartile do. Nearly one-third of those low-income students participate in neither sports nor club activities. (The overall nonparticipation rate is 10 percent.)

Using survey data from the National Center for Education Statistics, a team including Robert Putnam—whose book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis lays out a damning indictment of the nation’s exploding opportunity gap—found that affluent high schools offer about twice as many team sports as schools in high-poverty neighborhoods do. Those schools are also far less likely to require students to pay to play, as many poorer schools do—even in California, where the practice has been ruled unconstitutional. (Administrators evade the legal requirement by calling the fees “donations.”)

When the sociologists Elizabeth Stearns and Elizabeth Glennie used high school yearbooks to explore extracurricular opportunities in North Carolina, they found a similar pattern. Affluent schools offered more activities and had higher participation rates. This continuing disparity creates a vicious cycle because the experiences that allow students to distinguish themselves in the college application process also help keep kids in school. Poorer kids, already at higher risk of dropping out, have less opportunity to have the kind of experience that makes a young person love school and feel loved by it.

As damning as all of this is, the picture is even bleaker when we probe deeper into the breadth and quality of extracurricular experiences. Putnam’s team found that a high school senior from a rich family is about twice as likely as one from a poorer family to have served as a sports team captain. They also found significant gaps in access to private music, dance, and art lessons.

Participating in a high-quality Model United Nations program seems like the sort of experience that could change a young person’s life, and maybe even help them get into college. Of the Top 25 ranked Model UN programs, 10 are housed in private schools. Of the remaining 15, only one is hosted by a school whose student body is more than 10 percent Black. It’s no coincidence that Harvard and other elite colleges offer a proliferation of niche sports such as squash, fencing, and crew, that many disadvantaged kids have barely heard of, let alone participated in. A staggering 70 percent of recruited athletes at Harvard are white—a mere 3 percent of those white athletes are from economically disadvantaged families.

In 2017, Elizabeth Heaton, a college consultant who worked as an admissions officer at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote a piece for the Huffington Post titled, “What Kind of Hook Do I Need to Get Accepted to an Ivy League College?” It’s all about those distinguishing excellences, she argued. Being an Eagle Scout isn’t a distinguishing excellence, Heaton explained, because 50,000 kids achieve that rank every year. Valedictorians are a dime a dozen. So, too, are class presidents. Creating a nonprofit that solicits $1,000 and serves 500 meals isn’t a distinguishing excellence either. “But it can become one,” she wrote, “if you are raising $100,000 and serving 500,000 meals.” Her other examples included a debate champion, a “future global leader fluent in eight languages,” a USA Biology Olympiad winner, and a student who runs regional volunteer efforts for a US Senate campaign.

It’s hard to imagine a child of even ordinary means having any of these experiences. All are available only to families with wealth and connections. Who else has the access to get—and can afford to take—an unpaid internship in a high-profile political campaign? What child of ordinary means can win a science olympiad? For a fee, Heaton’s organization, Bright Horizons College Coach, will help you build a science profile that should suffice as a distinguishing excellence. Its Research Mentorship Program will match you “with a researcher from a top institution, such as Harvard, Princeton, Oxford, and MIT.” The goal is to develop a college-level research project that’s “a meaningful addition” to the college application. It also includes 10 mentoring sessions and help getting the work published or presented at a conference. Be forewarned: This program is only available to purchasers of the Premier and Elite plans.

Because college admissions officers may not be familiar with reverse-transcriptase inhibitors or machine-learning algorithms, distinguishing research needs to be translated into accessible language. Ideally, this language should include a narrative of personal growth that syncs with the sort of diversity that Harvard and its brethren value. Not to worry. Ivy Coach, Bright Horizons, and all the private college counselors will be more than happy to “edit” your college essays.

Maddeningly, but unsurprisingly, a team of researchers at Stanford found that the quality of an applicant’s essays has an even stronger correlation to reported household income than to their SAT score. Surely professional editing is exacerbating this disparity. Yet no elite college has a policy against this sort of assistance, even though it’d be easy to imagine, as Princeton Review founder John Katzman has proposed, requiring that students write their essays while sitting for one of the standardized exams.

Still, that’s not the worst of it. Elite colleges exacerbate the hoarding of opportunity by attaching value to distinguishing excellences. The message to parents is that they need to expose their children to elite extracurricular experiences to get them into elite colleges. This shapes the communities in which they live. Yet, paradoxically, almost everyone in the academy embraces the research (and often their own teaching experience) showing that the best predictors of wellbeing and achievement are characteristics like resilience, not academic or extracurricular brilliance.

Extracurriculars aren’t a reflection of a person’s inner wealth or value but of their opportunities. Working at Taco Bell or Burger King while going to high school isn’t something to be looked down upon. Rather, it’s a marker of resilience and a predictor of success—if only those students who need to work can overcome the prejudice against their experience and get themselves through those gilded gates. But there’s the rub. Working takes hours away from the time-intensive extracurriculars that elite colleges value.

At my stepson’s public high school commencement in a relatively affluent suburb, the school’s guidance director told parents that their children’s graduation was proof that “anyone can succeed.” She explained, “It’s just a matter of hard work.” Richard Rothstein, who wrote about the sordid history of racial redlining in his 2017 bestseller, The Color of Law, calls the belief that children born into low-income families can escape that status through hard work and education “a fantasy that we share.” It’s a fantasy in part because elite colleges don’t value hard work—or at least not hard work as it’s understood by and available to ordinary people. Instead, these schools value distinguishing excellences available only to the wealthy, and act as if weighing these experiences is the only conceivable mechanism by which to select capable students.

It isn’t.

After Graduating From Brandeis, Deborah Bial worked briefly as a paralegal, then took a job at CityKids, a foundation that uses art to help at-risk children find their voices. While there, she met a young man nicknamed Stein—short for Einstein—who’d given up a scholarship at a major university. When Bial asked why he’d dropped out, Stein said, “I could have done it if I had had my posse with me.”

Stein’s comment inspired Bial to start the Posse Foundation. It sends scholarship students in groups of 10—posses—to participating colleges so that they can support one another. The approach has been extraordinarily successful. Posse currently recruits students from 20 cities and has 63 partner colleges. Since its creation in 1989, Posse has selected more than 10,000 scholars who have received a cumulative $1.8 billion in scholarships. In 2007, Bial was awarded the prestigious MacArthur Foundation fellowship.

Posse is amazing, but Bial didn’t get a $500,000 so-called genius grant merely for sending kids to college in groups. She won it for how she picked the kids. Even in the late 1980s, Bial understood that the SAT systematically disadvantaged poor students, especially those who are Black or brown. She understood, too, long before the renowned psychologist Angela Duckworth recognized the power of determination, that people with the highest grades weren’t the ones who went on to succeed. If Bial wanted to cultivate a new generation of disadvantaged students who would go on to become leaders in their colleges and communities, she would need a different way to select people.

So she developed a test that measures initiative and persistence through group activities. The Bial-Dale College Adaptability Index is sometimes called the “Lego Test” because of a 10-minute segment that asks groups of students to reproduce a robot made of Lego blocks. The students are allowed to examine the structure individually but are prohibited from taking notes. Success requires cooperation and teamwork. In another part of the three-hour exam, rather than mirroring the traditional college interview, students are asked to lead a group discussion on a random topic. Observers note not who has the biggest vocabulary, but rather who collaborates well and who shows resilience.

How well does it work? Even though Posse is choosing among the most underserved students, those at the greatest risk of dropping out, more than 90 percent graduate. It’s difficult to imagine more definitive proof of something we all know in our hearts: The college interview is a scam. Unstructured interviews are notoriously bad at predicting future performance. What they do, rather, is reproduce social inequalities. People like people like them. So, the college interview becomes an exploration of shared experiences, even though many of those experiences are unavailable to poor applicants of color and an alternative system exists that’s better at predicting success. The sociologist Lauren Rivera has shown the same mechanisms at work in hiring at top law firms, investment banks, and management consulting companies.

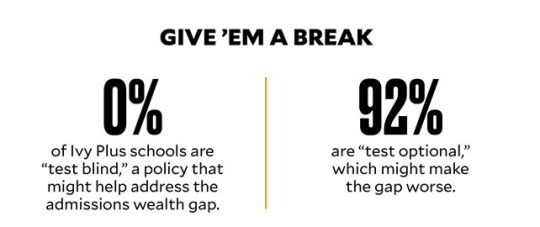

Even admissions practices that seem touchy-feely can skew the odds in the wrong direction. For instance, in the wake of widespread criticism that privileged families game the standardized-testing process, many colleges—including many of the Ivies—have made themselves test optional. But applicants can still submit SAT and ACT scores when it benefits them. That’s very different from schools that have made themselves “test-blind,” like the University of California, which no longer considers test scores at all.

“Superscoring” is even more offensive. That’s the common practice of counting only a student’s highest score from individual sections of the exam. The more times you take the exam, the greater your likelihood of having a superscore that exceeds your actual average. You can probably guess who takes these tests over and over. Economist Joshua Goodman, then at Harvard’s Kennedy School, and his collaborators looked at 10 million SAT takers from 2006 through 2014. Low-income students, they found, were 21 percent less likely to retake the exam—even though retaking it was worth about 90 points on the super-score and increased a low-income student’s chance of enrolling at a four-year college by nearly 30 . The effect was so strong, the authors concluded, that it explained about a quarter of the enrollment gap between low- and high-income students.

Most tragically, the status quo represents a lost opportunity. Imagine if we told communities that the skills elite colleges valued were cooperation, hard work, and listening. To be sure, the rich will learn to manipulate any system to sustain their class position. But think about what it would do for the perception of working-class people to signal that holding a real job signified something of honor and predicted success, instead of treating it as a disadvantage. Consider, too, what communities would look like if instead of creating incentives to hoard extracurricular opportunities and hire $100,000 consultants, colleges instead encouraged young people to be the best team players they could be.

It’s almost inevitable that the Supreme Court will dispense with affirmative action in the near future. That day will be tragic in a host of regards. Although reasonable minds can differ on whom should be given preference in college admissions, it’s hard to argue against the proposition that Harvard and other elite colleges—many of which were built with slave labor and with the benefit of racist housing practices—owe a debt to at least some of their applicants of color. But this obligation will almost certainly go unmet.

And it will largely be Harvard’s fault. No admissions system will ever be without controversy, but it’s important to remember how much opportunity Harvard could have created by ending its most offensive practices, such as tips for ALDCs. It could have admitted more Asian American applicants with high test scores and more socioeconomically disadvantaged students. Instead, the college acted as if the leg up it has historically afforded to affluent students is sacred, and in doing so it effectively pitted disadvantaged groups against one another. When the court ends affirmative action for low-income students of color, it will be the result of Harvard’s indignant commitment to affirmative action for wealthy white kids.

— MotherJones.Com

0 notes

Text

"Poison Ivy" author Evan Mandery: "Elite colleges are harmful to society"

“Poison Ivy” author Evan Mandery: “Elite colleges are harmful to society”

It was a surprising and — as the New York Times put it — “dramatic” set of announcements. On Wednesday, both Yale and Harvard decided to withdraw their law schools from consideration in the U.S. News & World Report rankings of the nation’s “best” institutions. In a statement, Yale Law School Dean Heather K. Gerken dropped the hammer, saying, “U.S. News rankings are profoundly flawed — they…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

TaxProf Blog

Saturday, October 1, 2022

This Week’s Ten Most Popular TaxProf Blog Posts

Bryan Camp (Texas Tech), Lesson From The Tax Court: Honor The Corporate Fiction

Evan Mandery (CUNY), What Trump Gets Right About Harvard

Arkansas Democrat Gazette, Arkansas Law Professor Files State Claim Over Denial Of Named Professorship With $10,250 Stipend

Wall Street Journal, If Legal Education Embraced Pay…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

Long, long article, but an easy read and extremely interesting and provocative.

#left/right#liberal/conservative#Democrat/Republican#divergent viewpoints#partisan divide#learning to listen#Evan Mandery

1 note

·

View note

Link

On the day the Supreme Court announced its decision in Furman v. Georgia, 45 men were on death row at the Ellis Unit in Huntsville, Texas. Newspapers described how the men erupted in cheers after the news came over their TVs and radios. Many believed that it was the end of capital punishment. The day after the ruling, on June 30, 1972, the San Antonio Express published a photo of the Texas electric chair with the caption “May Never Be Used Again.”

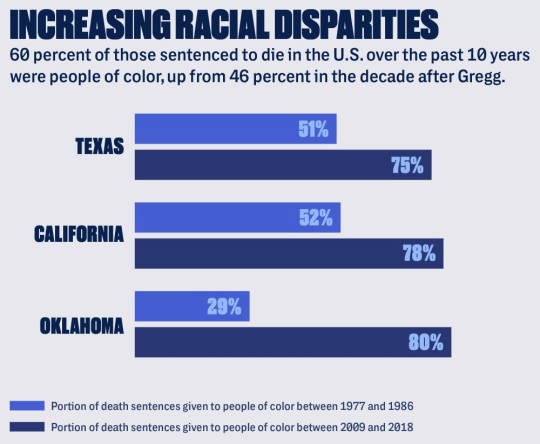

More than half of the 589 people spared by Furman were black. Among them was Elmer Branch, on death row in Texas. Twenty years old at the time of his arrest — and with a reported IQ of 67 — Branch had been sentenced to die for raping an elderly white woman in Vernon, Texas. He swore that he was innocent, but he was found guilty on the basis of eyewitness identification and a shoe print that matched his sneakers. When the Supreme Court announced that it would consider Furman back in 1971, the justices also took Branch’s case, along with another rape case out of Georgia. All three cases involved black defendants and white victims.

During the oral argument before the Supreme Court, Branch’s lawyer invoked the racism underlying his client’s case. A black man convicted of rape in Texas, he said, “has an 88 percent chance of receiving a death penalty,” compared to the 22 percent chance faced by non-black defendants. As in the rest of the South, such statistics were a direct legacy of lynchings and racial terror. The vast majority of the state’s death sentences handed out for rape came from East Texas, which once held the highest population of enslaved people in the state.

Furman, decided 5-4, was a tenuous and fractured ruling. Each justice wrote his own opinion, only two of which expressed opposition to capital punishment itself, rather than to how it was being applied. Most had little to say about racism, although the issue loomed large over the decision. The road that led to Furman had been paved in the 1960s by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, which had embarked on a data-driven mission that exposed racial bias in rape cases. As Justice Thurgood Marshall noted in his concurrence in Furman, of 455 people executed in the United States for rape since 1930, 405 had been black.

Nevertheless, lawyers had repeatedly failed to impress the courts with such statistics. Judges rejected the racial evidence as insufficient — although it is clear today that the deeper concern was that acknowledging racism would undermine the entire criminal justice system. The Supreme Court would eventually decide in McCleskey v. Kemp that racism in death sentences was inevitable, inoculating capital punishment from being challenged along racial lines. In the meantime, Furman was decided on the less controversial question of arbitrariness: the conclusion that the death penalty was “wantonly” and “freakishly” imposed, with no rhyme or reason guiding who should live and who should die.

While the Furman court mostly steered clear of race, the reaction to the ruling was fueled by racist fearmongering. Georgia’s segregationist lieutenant governor called the decision a “license for anarchy, rape, and murder,” according to Evan Mandery in “A Wild Justice: The Death and Resurrection of Capital Punishment.” At a press conference, President Richard Nixon, who’d won election on a wave of racially incendiary “law and order” rhetoric, defended executions as a deterrent. That day, Mandery writes, “legislators in five states announced plans to enact new death penalty statutes.”

Support for the death penalty skyrocketed. According to Mandery, in the last Harris Poll prior to Furman, 47 percent of respondents supported the death penalty, with 42 percent opposed. After Furman, a Harris Poll found 59 percent in favor. By the end of 1972, Florida became the first to pass a new death penalty law, followed by a slew of states the next year.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Et Tu, John Jay?

(photo courtesy of Getty)

: This op-ed was written by Evan J. Mandery, chairperson of the department of criminal justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

#MeToo strikes like lightning, it seems. Recently at my home for the past 19 years, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, a senior college at the City University of New York. The allegations are grave. They include the use and sale of drugs on campus, an effort to force women into prostitution, and rape.

The story has received only a modest amount of coverage—a pair of stories in The New York Post and one in the Times. Here at Above the Law, Elie Mystal argued that the scandal would have received more attention were it not for the Kavanaugh hearings. This seems likely true. But the stories that have been written are damning, and likely have already caused lasting damage to the college. “It’s hard to read these complaints and not come to the conclusion that the whole patriarchy needs to be BURNED TO THE GROUND,” Mystal wrote. “The only problem is that there don’t seem to be nearly enough matches.” It’s a jarring thing to read, and I couldn’t help but ask, is John Jay the patriarchy? Or, worse still, am I?

I’ve certainly never thought of John Jay as the patriarchy. To the contrary, the institution does more good than just about any I know. Our student body is stunningly diverse. Fifty-seven percent of our students are women. Forty-four percent identify themselves as Hispanic. Approximately 20% identify themselves as black, about the same percentage as identify themselves as white.

The median family income of a John Jay student is $41,900. (Point of comparison: at Colorado College the average is $277,500.) While virtually none of our students come from the top one percent, about 38% come from families making less than $30,000 per year. John Jay ranked ninth out of 2,137 colleges in the New York Times’s overall mobility index—the chance that a graduate will move up two or more income quintiles. I’ve seen miracles happen at John Jay. My former student, Abdoulaye Diallo, came to the U.S. from Guinea, taught himself English while working as a bicycle messenger, and 13 years ago landed in my freshman honors class. In June he graduated from Fordham Law School. Last week, he passed the bar.

Our college’s motto is “Fierce Advocates for Justice.” So far as I can tell, of the more than 7,000 colleges and universities in the United States, we’re the only one with “justice” in its title. Our faculty take the mission seriously. My colleagues are leaders in research on stop and frisk, neighborhood policing, false confessions, clergy abuse in the Catholic Church, child neglect and lead poisoning and innumerable other social justice topics. Most of our teaching shares the same orientation, and about half of our graduates go on to public service. (In the Ivy League, the figure ranges between 15 and 25 percent.)

I love John Jay. And yet, this.

Among my first reactions—no doubt borne of protectiveness for the college I so admire—is that we’re in the infancy of thinking about how to allocate institutional responsibility for sexual misconduct. The Weinstein Company is gone, but CBS and FOX seem to have suffered not at all, even though the allegations at the networks are most serious and concern leaders at the highest levels. It feels like John Jay will land somewhere in the middle. The college surely will endure, but every colleague I know has received calls and emails expressing dismay at the allegations, and it’s impossible to imagine that the institution will not suffer in its efforts to raise funds and attract research grants. Institutionally speaking, the meting of consequences feels arbitrary or, at the least, unsystematic.

This is hardly surprising. America has only begun to reckon with its legacy of tolerating sexual harassment and violence, and the ethics of institutional and collective responsibility have long divided philosophers. The prevailing view is that when people speak about “collective responsibility,” they are really talking about the individual responsibility of actors within the collective. For example, as Angelo Corlett has argued, when people say something like “Exxon is responsible for an oil spill” they’re really talking about the culpability of the corporation’s board members and high-level managers.

Hannah Arendt called it “senseless” to talk about collective guilt, as opposed to individual guilt, and said that the notion only served as a “whitewash” for guilty individuals to hide behind. Courts should deal with persons, she said, not “systems” or “isms.” Others, such as Joel Feinberg, who are more open to the concept, say that collective responsibility is only possible where the members have solidarity— “mutual interests, bonds of affection, and a ‘common lot.’” Question how many institutions share these characteristics. It certainly doesn’t well describe academia.

Though we may be unsure about when the complicity of bad actors implies institutional responsibility, we can make definitive statements about the institutional settings in which complicity is likely, and the institutional practices that are likely to produce abuse. To this point in the MeToo era, the focus has been on the facts of specific cases—the she said, he said. To be sure, bringing offenders to justice is vitally important. But litigating individual cases will never be a sufficient response, and it often won’t be satisfying because the kinds of behavior at issue rarely can be conclusively proven. This is because the subjective intent of the offender is relevant to the determination of criminal responsibility, even though it has little, if anything, to do with the victim’s experience.

The public focus would be better placed on the institutional settings likely to produce misconduct. About this, we know a great deal. Many were identified by my John Jay colleagues in their groundbreaking study of the Catholic church. “The opportunity structure for abusive behavior focuses on four factors: the authority of the priest, the public perception of them, the isolation of their positions, and the high level of discretion and lack of supervision in their positions.”

Focusing on these structural considerations would change the nature of the conversation about abuse. The Kavanaugh hearings did not lend themselves well to definitive statements of individual guilt, but we know conclusively that teenage drinking creates risk, and that college social clubs and fraternities are intensely problematic. Yet, few colleges entertain the idea of banning or reforming them. At John Jay, it’s impossible to say what the investigation will reveal, but we know for sure that the professoriate shares many of the church’s risk factors, and that abuse is common. Yet conversations about structural reform at universities are rare.

Why the reluctance to operationalize the patriarchy as a set of institutional practices likely to lead to violence against women? Perhaps it’s because the salacious details of individual allegations grab headlines. More likely it’s because doing so would implicate nearly every American cornerstone institution. For it is not only universities that share the structural features of the Catholic church—authority, high status, privacy and independence—it’s the medical profession, financial firms, the movie industry, and significantly to readers of this space, government, the judiciary and law firms.

Before entering academia, I spent my life working in the law and politics. In every institution at which I worked—each law firm, judicial chamber, political campaign and government office, I witnessed sexual harassment first hand. And that was the public conduct. I can only imagine what happened behind closed doors.

Some of these men have come to justice. Most have not. That’s the random, lightning strike feel of Me Too. While we can admire the handful of women brave enough to withstand the firestorm of levying public accusations against high-profile men, we should not overlook the institutional practices that lead to these sorts of tragedies. We know unequivocally that we have only scratched the surface of uncovering sexual assault—the most underreported of crimes, and we know simple practices that can make worlds of difference—promoting social norms that protect against violence, creating protective environments, and support for reporting victims.

But opening these conversations will force a broader reckoning than any of us can bear. Because by this logic, we’re all part of the patriarchy.

0 notes

Link

Analysts say an indictment is likely as prosecutors focus on Giuliani’s work for Trump and himself in UkraineRudy Giuliani: ‘The president knows that everything I did, I did to help him.’ Photograph: Charles Krupa/APWhen the former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani emerged as one of Donald Trump’s most bareknuckle defenders during the Russia investigation, attacking his former colleagues in the justice department, people asked: “What happened to Rudy?”Now, as federal prosecutors tighten a net of criminal investigations around Giuliani, the question has become: “What is going to happen to Rudy?”The poignancy of Giuliani’s downfall from national hero and presidential candidate to the subject of multiple federal criminal investigations has been often remarked in the past year.The net tightened again last week when it emerged a grand jury had issued a broad subpoena for documents relating to Giuliani’s international consulting business as part of an investigation of alleged crimes including money laundering, wire fraud, campaign finance violations, making false statements, obstruction of justice, and violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act.“We who admired him for so long expected much more from Rudy Giuliani and his legacy,” Ken Frydman, a former Giuliani press secretary, wrote in a New York Times opinion piece last month. “‘America’s Mayor,’ as Rudy was called after September 11, is today President Trump’s bumbling personal lawyer and henchman, his apologist and defender of the indefensible.”Giuliani has denied wrongdoing and scoffed at the notion he is in any legal jeopardy – particularly from federal prosecutors in the southern district of New York, an office he once led as a star US attorney during Ronald Reagan’s first term. There Giuliani built a reputation for taking on mob bosses and aggressively prosecuting the kind of criminal activity he now stands accused of.“Me ending up in jail?” Giuliani told the celebrity gossip site TMZ at a Washington airport on Monday. “Fifty years of being a lawyer, 50 years of ethical, dedicated practice of the law, probably have prosecuted more criminals of a high level than any US attorney in history. I think I follow the law very carefully. I think the people pursuing me are desperate, sad, angry, disappointing liars. They’re hurting their country. And I’m ashamed of them.”But in no version of events does Giuliani appear not to be in big trouble.The immediate source of his current problems is the work he did in Ukraine over the last two years for himself and on behalf of Trump, who instructed the Ukrainian president to speak to Giuliani in a 25 July phone call.Giuliani wanted the Ukrainians to announce an investigation of Joe Biden, Trump’s chief political rival, according to US officials who testified in the impeachment hearings. In pursuit of his errand, Giuliani contacted current and former Ukrainian prosecutors, multiple Ukrainian presidential administrations and multiple Ukrainian oligarchs, according to testimony.Prosecutors are investigating whether Giuliani offered the oligarchs help with their problems with the US justice department in exchange for help with his project to harm Biden, a charge Giuliani has denied.Rudy Giuliani’s business associates Lev Parnas, left, and Igor Fruman sit either side of lawyer during their arraignment in New York City on 23 October. Photograph: Jane Rosenberg/ReutersTwo Soviet Union-born American associates of Giuliani, Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, were arrested last month on campaign finance charges, and Parnas is cooperating with investigators. Alongside the prosecutors in New York, the US justice department in Washington is also investigating Giuliani’s conduct, as is the Federal Bureau of Investigation.Congress is also after Giuliani, who came in for sharp public criticism in the impeachment hearings earlier this month, when Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch described a smear campaign Giuliani had mounted against her, allegedly because as an anti-corruption advocate she stood in the way of Trump’s Ukraine scheme.“I do not understand Mr Giuliani’s motives for attacking me,” Yovanovitch testified. “What I can say is that Mr Giuliani should have known those claims were suspect, coming as they reportedly did from individuals with questionable motives and with reason to believe that their political and financial ambitions would be stymied by our anti-corruption policy in Ukraine.”As the pressure on him has intensified, Giuliani’s antics in his own defense have grown increasingly animated. He warned last week that he had collected information that would put his political enemies on their heels.“I’m also going to bring out a pay-for-play scheme in the Obama administration that will be devastating to the Democrat party,” Giuliani told Fox News. He even threatened to start an impeachment podcast.Giuliani on Trump: ‘We are friends for twenty-nine29 years and nothing will interfere with that.’ Photograph: Don Emmert/AFP/Getty ImagesBut what matters most for Giuliani right now is his long friendship with Trump, his most powerful protector, which goes back to the late 1980s, when Trump served as co-chair of Giuliani’s first fundraiser for his 1989 mayoral campaign, according to Wayne Barrett, who has written books about both men.In a telephone interview with the Guardian, in response to a question about whether he was nervous that Trump might “throw him under a bus” in the impeachment crisis, Giuliani said: “I’m not, but I do have very, very good insurance, so if he does, all my hospital bills will be paid.”Giuliani’s lawyer, Robert Costello, who was also on the call, then interjected: “He’s joking.”“We are friends for 29 years and nothing will interfere with that,” Giuliani told TMZ of Trump. “The president knows that everything I did, I did to help him. And he knows it. I did it honorably. I did it legally. I did it in a way that it will embarrass the people who are pursuing me and have nowhere near the integrity and honor that I have.”Trump has tweeted that Giuliani “may seem a little rough around the edges sometimes, but he is also a great guy and wonderful lawyer”.In an interview with disgraced former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly last Tuesday, however, Trump distanced himself from Giuliani. Analysts watching Giuliani’s case expect that an indictment could be handed down at any moment, raising the prospect of America’s Mayor in handcuffs.“If Rudy’s story ends the way it feels like it’s going to end,” wrote Evan Mandery, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and veteran of New York City political campaigns, “it’s not plausible for anyone who knows or has studied him to say they never saw it coming.”

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://ift.tt/2Y5Hjig

0 notes

Link

Analysts say an indictment is likely as prosecutors focus on Giuliani’s work for Trump and himself in UkraineRudy Giuliani: ‘The president knows that everything I did, I did to help him.’ Photograph: Charles Krupa/APWhen the former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani emerged as one of Donald Trump’s most bareknuckle defenders during the Russia investigation, attacking his former colleagues in the justice department, people asked: “What happened to Rudy?”Now, as federal prosecutors tighten a net of criminal investigations around Giuliani, the question has become: “What is going to happen to Rudy?”The poignancy of Giuliani’s downfall from national hero and presidential candidate to the subject of multiple federal criminal investigations has been often remarked in the past year.The net tightened again last week when it emerged a grand jury had issued a broad subpoena for documents relating to Giuliani’s international consulting business as part of an investigation of alleged crimes including money laundering, wire fraud, campaign finance violations, making false statements, obstruction of justice, and violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act.“We who admired him for so long expected much more from Rudy Giuliani and his legacy,” Ken Frydman, a former Giuliani press secretary, wrote in a New York Times opinion piece last month. “‘America’s Mayor,’ as Rudy was called after September 11, is today President Trump’s bumbling personal lawyer and henchman, his apologist and defender of the indefensible.”Giuliani has denied wrongdoing and scoffed at the notion he is in any legal jeopardy – particularly from federal prosecutors in the southern district of New York, an office he once led as a star US attorney during Ronald Reagan’s first term. There Giuliani built a reputation for taking on mob bosses and aggressively prosecuting the kind of criminal activity he now stands accused of.“Me ending up in jail?” Giuliani told the celebrity gossip site TMZ at a Washington airport on Monday. “Fifty years of being a lawyer, 50 years of ethical, dedicated practice of the law, probably have prosecuted more criminals of a high level than any US attorney in history. I think I follow the law very carefully. I think the people pursuing me are desperate, sad, angry, disappointing liars. They’re hurting their country. And I’m ashamed of them.”But in no version of events does Giuliani appear not to be in big trouble.The immediate source of his current problems is the work he did in Ukraine over the last two years for himself and on behalf of Trump, who instructed the Ukrainian president to speak to Giuliani in a 25 July phone call.Giuliani wanted the Ukrainians to announce an investigation of Joe Biden, Trump’s chief political rival, according to US officials who testified in the impeachment hearings. In pursuit of his errand, Giuliani contacted current and former Ukrainian prosecutors, multiple Ukrainian presidential administrations and multiple Ukrainian oligarchs, according to testimony.Prosecutors are investigating whether Giuliani offered the oligarchs help with their problems with the US justice department in exchange for help with his project to harm Biden, a charge Giuliani has denied.Rudy Giuliani’s business associates Lev Parnas, left, and Igor Fruman sit either side of lawyer during their arraignment in New York City on 23 October. Photograph: Jane Rosenberg/ReutersTwo Soviet Union-born American associates of Giuliani, Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, were arrested last month on campaign finance charges, and Parnas is cooperating with investigators. Alongside the prosecutors in New York, the US justice department in Washington is also investigating Giuliani’s conduct, as is the Federal Bureau of Investigation.Congress is also after Giuliani, who came in for sharp public criticism in the impeachment hearings earlier this month, when Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch described a smear campaign Giuliani had mounted against her, allegedly because as an anti-corruption advocate she stood in the way of Trump’s Ukraine scheme.“I do not understand Mr Giuliani’s motives for attacking me,” Yovanovitch testified. “What I can say is that Mr Giuliani should have known those claims were suspect, coming as they reportedly did from individuals with questionable motives and with reason to believe that their political and financial ambitions would be stymied by our anti-corruption policy in Ukraine.”As the pressure on him has intensified, Giuliani’s antics in his own defense have grown increasingly animated. He warned last week that he had collected information that would put his political enemies on their heels.“I’m also going to bring out a pay-for-play scheme in the Obama administration that will be devastating to the Democrat party,” Giuliani told Fox News. He even threatened to start an impeachment podcast.Giuliani on Trump: ‘We are friends for twenty-nine29 years and nothing will interfere with that.’ Photograph: Don Emmert/AFP/Getty ImagesBut what matters most for Giuliani right now is his long friendship with Trump, his most powerful protector, which goes back to the late 1980s, when Trump served as co-chair of Giuliani’s first fundraiser for his 1989 mayoral campaign, according to Wayne Barrett, who has written books about both men.In a telephone interview with the Guardian, in response to a question about whether he was nervous that Trump might “throw him under a bus” in the impeachment crisis, Giuliani said: “I’m not, but I do have very, very good insurance, so if he does, all my hospital bills will be paid.”Giuliani’s lawyer, Robert Costello, who was also on the call, then interjected: “He’s joking.”“We are friends for 29 years and nothing will interfere with that,” Giuliani told TMZ of Trump. “The president knows that everything I did, I did to help him. And he knows it. I did it honorably. I did it legally. I did it in a way that it will embarrass the people who are pursuing me and have nowhere near the integrity and honor that I have.”Trump has tweeted that Giuliani “may seem a little rough around the edges sometimes, but he is also a great guy and wonderful lawyer”.In an interview with disgraced former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly last Tuesday, however, Trump distanced himself from Giuliani. Analysts watching Giuliani’s case expect that an indictment could be handed down at any moment, raising the prospect of America’s Mayor in handcuffs.“If Rudy’s story ends the way it feels like it’s going to end,” wrote Evan Mandery, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and veteran of New York City political campaigns, “it’s not plausible for anyone who knows or has studied him to say they never saw it coming.”

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://ift.tt/2Y5Hjig

0 notes

Link

Analysts say an indictment is likely as prosecutors focus on Giuliani’s work for Trump and himself in UkraineRudy Giuliani: ‘The president knows that everything I did, I did to help him.’ Photograph: Charles Krupa/APWhen the former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani emerged as one of Donald Trump’s most bareknuckle defenders during the Russia investigation, attacking his former colleagues in the justice department, people asked: “What happened to Rudy?”Now, as federal prosecutors tighten a net of criminal investigations around Giuliani, the question has become: “What is going to happen to Rudy?”The poignancy of Giuliani’s downfall from national hero and presidential candidate to the subject of multiple federal criminal investigations has been often remarked in the past year.The net tightened again last week when it emerged a grand jury had issued a broad subpoena for documents relating to Giuliani’s international consulting business as part of an investigation of alleged crimes including money laundering, wire fraud, campaign finance violations, making false statements, obstruction of justice, and violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act.“We who admired him for so long expected much more from Rudy Giuliani and his legacy,” Ken Frydman, a former Giuliani press secretary, wrote in a New York Times opinion piece last month. “‘America’s Mayor,’ as Rudy was called after September 11, is today President Trump’s bumbling personal lawyer and henchman, his apologist and defender of the indefensible.”Giuliani has denied wrongdoing and scoffed at the notion he is in any legal jeopardy – particularly from federal prosecutors in the southern district of New York, an office he once led as a star US attorney during Ronald Reagan’s first term. There Giuliani built a reputation for taking on mob bosses and aggressively prosecuting the kind of criminal activity he now stands accused of.“Me ending up in jail?” Giuliani told the celebrity gossip site TMZ at a Washington airport on Monday. “Fifty years of being a lawyer, 50 years of ethical, dedicated practice of the law, probably have prosecuted more criminals of a high level than any US attorney in history. I think I follow the law very carefully. I think the people pursuing me are desperate, sad, angry, disappointing liars. They’re hurting their country. And I’m ashamed of them.”But in no version of events does Giuliani appear not to be in big trouble.The immediate source of his current problems is the work he did in Ukraine over the last two years for himself and on behalf of Trump, who instructed the Ukrainian president to speak to Giuliani in a 25 July phone call.Giuliani wanted the Ukrainians to announce an investigation of Joe Biden, Trump’s chief political rival, according to US officials who testified in the impeachment hearings. In pursuit of his errand, Giuliani contacted current and former Ukrainian prosecutors, multiple Ukrainian presidential administrations and multiple Ukrainian oligarchs, according to testimony.Prosecutors are investigating whether Giuliani offered the oligarchs help with their problems with the US justice department in exchange for help with his project to harm Biden, a charge Giuliani has denied.Rudy Giuliani’s business associates Lev Parnas, left, and Igor Fruman sit either side of lawyer during their arraignment in New York City on 23 October. Photograph: Jane Rosenberg/ReutersTwo Soviet Union-born American associates of Giuliani, Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, were arrested last month on campaign finance charges, and Parnas is cooperating with investigators. Alongside the prosecutors in New York, the US justice department in Washington is also investigating Giuliani’s conduct, as is the Federal Bureau of Investigation.Congress is also after Giuliani, who came in for sharp public criticism in the impeachment hearings earlier this month, when Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch described a smear campaign Giuliani had mounted against her, allegedly because as an anti-corruption advocate she stood in the way of Trump’s Ukraine scheme.“I do not understand Mr Giuliani’s motives for attacking me,” Yovanovitch testified. “What I can say is that Mr Giuliani should have known those claims were suspect, coming as they reportedly did from individuals with questionable motives and with reason to believe that their political and financial ambitions would be stymied by our anti-corruption policy in Ukraine.”As the pressure on him has intensified, Giuliani’s antics in his own defense have grown increasingly animated. He warned last week that he had collected information that would put his political enemies on their heels.“I’m also going to bring out a pay-for-play scheme in the Obama administration that will be devastating to the Democrat party,” Giuliani told Fox News. He even threatened to start an impeachment podcast.Giuliani on Trump: ‘We are friends for twenty-nine29 years and nothing will interfere with that.’ Photograph: Don Emmert/AFP/Getty ImagesBut what matters most for Giuliani right now is his long friendship with Trump, his most powerful protector, which goes back to the late 1980s, when Trump served as co-chair of Giuliani’s first fundraiser for his 1989 mayoral campaign, according to Wayne Barrett, who has written books about both men.In a telephone interview with the Guardian, in response to a question about whether he was nervous that Trump might “throw him under a bus” in the impeachment crisis, Giuliani said: “I’m not, but I do have very, very good insurance, so if he does, all my hospital bills will be paid.”Giuliani’s lawyer, Robert Costello, who was also on the call, then interjected: “He’s joking.”“We are friends for 29 years and nothing will interfere with that,” Giuliani told TMZ of Trump. “The president knows that everything I did, I did to help him. And he knows it. I did it honorably. I did it legally. I did it in a way that it will embarrass the people who are pursuing me and have nowhere near the integrity and honor that I have.”Trump has tweeted that Giuliani “may seem a little rough around the edges sometimes, but he is also a great guy and wonderful lawyer”.In an interview with disgraced former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly last Tuesday, however, Trump distanced himself from Giuliani. Analysts watching Giuliani’s case expect that an indictment could be handed down at any moment, raising the prospect of America’s Mayor in handcuffs.“If Rudy’s story ends the way it feels like it’s going to end,” wrote Evan Mandery, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and veteran of New York City political campaigns, “it’s not plausible for anyone who knows or has studied him to say they never saw it coming.”

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://ift.tt/2Y5Hjig

0 notes

Link

Analysts say an indictment is likely as prosecutors focus on Giuliani’s work for Trump and himself in UkraineRudy Giuliani: ‘The president knows that everything I did, I did to help him.’ Photograph: Charles Krupa/APWhen the former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani emerged as one of Donald Trump’s most bareknuckle defenders during the Russia investigation, attacking his former colleagues in the justice department, people asked: “What happened to Rudy?”Now, as federal prosecutors tighten a net of criminal investigations around Giuliani, the question has become: “What is going to happen to Rudy?”The poignancy of Giuliani’s downfall from national hero and presidential candidate to the subject of multiple federal criminal investigations has been often remarked in the past year.The net tightened again last week when it emerged a grand jury had issued a broad subpoena for documents relating to Giuliani’s international consulting business as part of an investigation of alleged crimes including money laundering, wire fraud, campaign finance violations, making false statements, obstruction of justice, and violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act.“We who admired him for so long expected much more from Rudy Giuliani and his legacy,” Ken Frydman, a former Giuliani press secretary, wrote in a New York Times opinion piece last month. “‘America’s Mayor,’ as Rudy was called after September 11, is today President Trump’s bumbling personal lawyer and henchman, his apologist and defender of the indefensible.”Giuliani has denied wrongdoing and scoffed at the notion he is in any legal jeopardy – particularly from federal prosecutors in the southern district of New York, an office he once led as a star US attorney during Ronald Reagan’s first term. There Giuliani built a reputation for taking on mob bosses and aggressively prosecuting the kind of criminal activity he now stands accused of.“Me ending up in jail?” Giuliani told the celebrity gossip site TMZ at a Washington airport on Monday. “Fifty years of being a lawyer, 50 years of ethical, dedicated practice of the law, probably have prosecuted more criminals of a high level than any US attorney in history. I think I follow the law very carefully. I think the people pursuing me are desperate, sad, angry, disappointing liars. They’re hurting their country. And I’m ashamed of them.”But in no version of events does Giuliani appear not to be in big trouble.The immediate source of his current problems is the work he did in Ukraine over the last two years for himself and on behalf of Trump, who instructed the Ukrainian president to speak to Giuliani in a 25 July phone call.Giuliani wanted the Ukrainians to announce an investigation of Joe Biden, Trump’s chief political rival, according to US officials who testified in the impeachment hearings. In pursuit of his errand, Giuliani contacted current and former Ukrainian prosecutors, multiple Ukrainian presidential administrations and multiple Ukrainian oligarchs, according to testimony.Prosecutors are investigating whether Giuliani offered the oligarchs help with their problems with the US justice department in exchange for help with his project to harm Biden, a charge Giuliani has denied.Rudy Giuliani’s business associates Lev Parnas, left, and Igor Fruman sit either side of lawyer during their arraignment in New York City on 23 October. Photograph: Jane Rosenberg/ReutersTwo Soviet Union-born American associates of Giuliani, Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, were arrested last month on campaign finance charges, and Parnas is cooperating with investigators. Alongside the prosecutors in New York, the US justice department in Washington is also investigating Giuliani’s conduct, as is the Federal Bureau of Investigation.Congress is also after Giuliani, who came in for sharp public criticism in the impeachment hearings earlier this month, when Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch described a smear campaign Giuliani had mounted against her, allegedly because as an anti-corruption advocate she stood in the way of Trump’s Ukraine scheme.“I do not understand Mr Giuliani’s motives for attacking me,” Yovanovitch testified. “What I can say is that Mr Giuliani should have known those claims were suspect, coming as they reportedly did from individuals with questionable motives and with reason to believe that their political and financial ambitions would be stymied by our anti-corruption policy in Ukraine.”As the pressure on him has intensified, Giuliani’s antics in his own defense have grown increasingly animated. He warned last week that he had collected information that would put his political enemies on their heels.“I’m also going to bring out a pay-for-play scheme in the Obama administration that will be devastating to the Democrat party,” Giuliani told Fox News. He even threatened to start an impeachment podcast.Giuliani on Trump: ‘We are friends for twenty-nine29 years and nothing will interfere with that.’ Photograph: Don Emmert/AFP/Getty ImagesBut what matters most for Giuliani right now is his long friendship with Trump, his most powerful protector, which goes back to the late 1980s, when Trump served as co-chair of Giuliani’s first fundraiser for his 1989 mayoral campaign, according to Wayne Barrett, who has written books about both men.In a telephone interview with the Guardian, in response to a question about whether he was nervous that Trump might “throw him under a bus” in the impeachment crisis, Giuliani said: “I’m not, but I do have very, very good insurance, so if he does, all my hospital bills will be paid.”Giuliani’s lawyer, Robert Costello, who was also on the call, then interjected: “He’s joking.”“We are friends for 29 years and nothing will interfere with that,” Giuliani told TMZ of Trump. “The president knows that everything I did, I did to help him. And he knows it. I did it honorably. I did it legally. I did it in a way that it will embarrass the people who are pursuing me and have nowhere near the integrity and honor that I have.”Trump has tweeted that Giuliani “may seem a little rough around the edges sometimes, but he is also a great guy and wonderful lawyer”.In an interview with disgraced former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly last Tuesday, however, Trump distanced himself from Giuliani. Analysts watching Giuliani’s case expect that an indictment could be handed down at any moment, raising the prospect of America’s Mayor in handcuffs.“If Rudy’s story ends the way it feels like it’s going to end,” wrote Evan Mandery, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and veteran of New York City political campaigns, “it’s not plausible for anyone who knows or has studied him to say they never saw it coming.”

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://ift.tt/2Y5Hjig

0 notes