#felt like he was performing a ritual or séance

Text

yeah so this part has a chokehold on me

#felt like he was performing a ritual or séance#we are a part of a cult#never thought i’d be here but hey#greta van fleet#josh kiszka#jake kiszka#danny wagner#sam kiszka#sammy kiszka#danny gvf#jake gvf#josh gvf#sam gvf#meeting the master music video#meeting the master#mtm#meeting the master mv#meeting the master gvf#gvf

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

Witchcraft Asks # 26-30

----

26. What got you interested in witchcraft?

I can't remember a time when I wasn't interested in witchcraft. I did a séance once with a spell in my haunted house when I was a teen. I found out I am mostly haunted, not the house. But, I think I fully placed my feet in the water around 2019, and it just felt familiar and home-ly.

--

27. Have you ever performed a spell or ritual with the company of anyone who was not a witch?

Yes. I had a few clients whom asked me to remove hexes or banish unwanted spirits. Otherwise, I don't let a lot of people know I do spells or rituals. Why would I want to show the locals here my cards?

--

28. Have you ever used ouija?

Yes. Nothing really happened but I made sure to close any portal that might've opened ASAP. Do I believe in it? Sure, but I don't use it anymore.

--

29. Do you consider yourself a psychic?

Yes. I believe so. To be honest, I didn't believe in psychics and I still challenge the aspect of what makes someone psychic. Despite my disbelief, I had visions foretelling near-distant disasters that may be coming for someone if something doesn't change. I didn't really took it seriously of course when I saw them...until they happened exactly as I had seen it. I can physically see spirits and entities at times. I wont' share everything pertaining to this topic, I like to keep some cards to myself.

--

30. Do you have a spirit guide? If so, what is it?

I actually don't believe in some concepts of what makes a spirit guide. They could be wrong, but I was often-ly told that spirit guides supposedly serve you by guiding you around in life. I don't know how popular that assumption is, but I don't believe it. I just believe that some big-hearted ancestors or spirits/entities that are just nice would flock by tell me what I am needing to evaluate, then leave to live their lives.

As for who they are? I got a lot of loving help from my Family; my spirit Family. Sometimes I see passing entities or spirits that takes the form of forest animals like bears, elks, wolves, etc. giving me subtle hints and go.

If I have to say who's the closest to a "spirit guide," it's a jinn. He's the closest to me. I won't speak his name nor give too much information, he loves privacy and he's wary of any outsiders.

#witchcraft#witch#spirit work#spirit companion#spirit companionship#spirit guides#ask the witch#psychic

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

‘Exuma’ at 50: How a Bahamian Artist Channeled Island Culture Into a Strange Sonic Ritual by Brenna Ehrlich

The performer known as Exuma channeled his Bahamian heritage into a captivating 1970 debut. Fans and participants look back.

Chances are, you’ve never heard a boast track quite like “Exuma, the Obeah Man,” the opening song off Exuma’s self-titled 1970 album.

A wolf howls, frogs count off a ramshackle symphony, bells jingle, drums palpitate, a zombie exhales, all by way of introducing the one-of-a-kind Bahamian performer, born Tony Mackey: “I came down on a lightning bolt/Nine months in my mama’s belly,” he proclaims. “When I was born, the midwife/Screamed and shout/I had fire and brimstone/Coming out of my mouth/I’m Exuma, the Obeah Man.”

“[Obeah] was with my grandfather, with my father, with my mother, with my uncles who taught me,” Mackey said in a 1970 interview, referring to the spiritual practice he grew up with in the Bahamas. “It has been my religion in the vein that everyone has grown up with some sort of religion, a cult that was taught. Christianity is like good and evil. God is both. He unlocked the secrets to Moses, good and evil, so Moses could help the children of Israel. It’s the same thing, the whole completeness — the Obeah Man, spirits of air.”

The music world is hardly devoid of gimmicks, alter egos, and adopted personas. But Mackey’s Exuma moniker, borrowed from the name of an island district in the Bahamas, was never just that — he lived and breathed his culture, channeling it into a debut album so singularly weird, wonderful, and enchanted that it’s not surprising it’s remembered only by the most industrious of crate-diggers. A cuddly Dr. John dabbling in voodoo Mackey was not; Exuma is a parade, a séance, a condemnation of racist evils.

“The eccentricity of [Dr. John’s 1968 debut] Gris-Gris is, like, ‘Let’s roll a fat joint,'” says Okkervil River frontman and devout Exuma fan Will Sheff. “The eccentricity of Exuma is more like PCP.” Sheff became hip to Exuma when his former bandmate Jonathan Meiburg (singer-guitarist of Shearwater) happened to hear “Obeah Woman,” Nina Simone’s 1974 spin on “Obeah Man.” Sheff was entranced by Exuma’s debut, especially the sincerity of its lyrics and Mackey’s whole-hearted earnestness. “There’s something about when somebody is very devoutly religious, where you trust them not to sell you something,” he tells Rolling Stone. “I mean, they may be trying to sell you their religious beliefs, but their religious beliefs are so vitally important to them that they kind of stop trying to sell themselves.”

youtube

“He was unique. He was good,” says Quint Davis, producer of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, where Exuma became a mainstay later in his career. “He was like a voodoo Richie Havens or something.”

Macfarlane Gregory Anthony Mackey grew up in Nassau, Bahamas, steeped in both Bahamian history and American culture. Each Boxing Day, he witnessed Junkanoo parades — a tradition dating back hundreds of years and commemorating days when slaves finally had time off — replete with music, masks, and folklore. At the movies, accessed with pocket money earned from selling fish on weekends, he saw performances by Sam Cooke and Fats Domino.

“Saying the word ‘Junkanoo’ to most Bahamians gets their hearts beating faster and their breathing gets shorter and faster,” Langston Longley, leader of Bahamas Junkanoo Revue, has said. “It’s hard to express in words because it’s a feeling, a spirit that’s evoked within from the sound of a goatskin drum, a cowbell, or a bugle.”

“I grew up a roots person, someone knowing about the bush and the herbs and the spiritual realm,” Mackey told Wavelength in 1981 of his life back home. “It was inbred into all of us. Just like for people growing up in the lowlands of Delta Country or places like Africa.”

In 1961, when he was 17, Mackey moved to New York’s Greenwich Village to become an architect, according to a 1970 interview, but he abandoned that dream when he ran out of money. He then acquired a junked-up guitar on which he practiced Bahamian calypsos and penned songs about his home. “I started playing around when Bob Dylan, Richie Havens, Peter, Paul, and Mary, Richard Pryor, Hendrix, and Streisand were all down there, too, hanging out and performing at the Cafe Bizarre,” Mackey recalled in 1994. “I’d been singing down there, and we’d all been exchanging ideas and stuff. Then one time a producer came up to me and said he was very interested in recording some of my original songs, but he said that I needed a vehicle. I remembered the Obeah Man from my childhood — he’s the one with the colorful robes who would deal with the elements and the moonrise, the clouds, and the vibrations of the earth. So, I decided to call myself Exuma, the Obeah Man.”

youtube

Mackey’s manager, Bob Wyld, helped him form a band to record his debut album, including Wyld’s client Peppy Castro of the Blues Magoos. “It was like acting. Like, ‘OK, I’ll take a little alias, I’ll be Spy Boy,’ and all this kind of stuff,” Castro tells Rolling Stone. All the members of Mackey’s band adopted stage names, which wasn’t that strange to Castro, who originated the role of Berger in the Broadway show Hair.

“Then I met Tony and then I got into the folklore and I started to see what he was about — this history of coming from the [Bahamas],” he adds. “It was great. It was inventive. We would do a little Junkanoo parade from out of the dressing room, right up to the stage. It was about the show of it all. Coming from somebody who wanted to learn music in a more traditional form, that was kind of cool.”

The band recorded Exuma at Bob Liftin’s Regent Sound Studios in New York City — where the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, and Elton John also laid down tracks — giving the bizarre record a slick sheen. Mackey once said that the music came to him in a dream, and he set the mood in the studio accordingly. “It was so free form. We turned the lights out, we’d put up candles, he’d get on a mic and he’d just start going off and singing crazy stuff and we followed it,” Castro says. “You would go into trances. In those days, I was a little hippie, so yeah, we’d be smoking weed there and getting high. It became a séance almost. It was like, ‘We’re going into this mode and we’re going to see where it takes us.’”

youtube

“There were no boundaries with Tony,” he adds. “It was free for him. It’s kind of like what people felt like when they played with Chuck Berry. If you talk to any of the musicians who played with Chuck Berry, you just had to be on your toes because he would change keys in the middle of the song. But there was also the spiritual stuff, you know, just the crazy voodoo-ish stuff. It was just so free for him.”

Everyone Rolling Stone talked with for this story compared Mackey to Richie Havens, but the similarities only really extend to, perhaps, Havens’ role in the Greenwich Village scene and the rich quality of his voice. “You can put on Dr. John and Richie Havens and water the plants. It’s good background music,” Will Sheff says. “But if [Exuma’s] ‘Séance in the Sixth Fret’ comes on shuffle, you’re going to skip it. It’s active listening; it sends a chill down your spine.”

Exuma is a kind of aural movie — fitting, as Mackey went on to write plays — that starts off boastful and proud with “Obeah Man” then descends into darker territory. The second track, “Dambala,” is a melodic damnation of slave owners: “You slavers will know/What it’s like to be a slave,” Mackey wails, “You’ll remain in your graves/With the stench and the smell.”

“It reminds me of Jordan Peele movies — movies that deal with sort of the black experience, a collective trauma,” Sheff says of the song. “He’s cursing a slaver and there’s something so intensely powerful about that.”

Then there’s zombie ode “Mama Loi, Papa Loi,” a frankly terrifying story of men rising from the dead, featuring guttural yelps and groans. “Jingo, Jingo he ain’t dead/He can see from the back of his head,” Mackey sings. That leads into the comparatively peppy “Junkanoo,” an instrumental that recalls the parades of the musician’s youth. Things get dark again with “Séance in the Sixth Fret,” which is just that — a yearning ritual in which the band calls to a litany of spirits. “Hand on quill/Hand on pencil/Hand on pen/Tell me spirit/Tell me when,” Mackey intones. The more accessible “You Don’t Know What’s Going On,” follows, leading into epic prophecy “The Vision,” which foretells the end of the world: “And all the dead walking throughout the land/Whispering, Whispering, it was judgment day.”

The strange, gorgeous record was released on Mercury Records, and at the time, the label had high hopes for its success, as it was apparently getting solid radio play. “The reaction is that of a heavy, big-numbers contemporary album,” Mercury exec Lou Simon said at the time. “As a result, we’re going to give it all the merchandising support we can muster.” But the album apparently failed to break through, and Mackey left Mercury in 1971 after releasing Exuma II. His legacy lived on in the corners of popular culture: Nina Simone covered “Dambala” as well as “Obeah Man,” with both tracks appearing on It Is Finished, a 1974 LP that failed to take off. Mackey himself went on to drop still more albums but mostly operated in a quiet kind of obscurity.

youtube

“What he didn’t have was the commercial base, you know, the formula,” Castro says by way of explanation. “Let’s face it, the music business is very fickle and it boxes you in. And if you’re going to join that world, it’s in your best interest to commercialize yourself and to come up with a formula that works. He didn’t have that formula.”

youtube

Mackey did find a home, though, at the newly minted New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1978, an atmosphere that seemed more in keeping with his spiritual aesthetic than mainstream radio. “New Orleans is the most receptive place in the world to the artist, this music spirit that flies around in the air all the time waiting to be reborn and reborn,” he told Wavelength in 1981.

“He was a Caribbean Dr. John, so to speak,” festival producer Davis says. “When I heard [his album], I said, ‘Well, that’s us.’ This guy with feathers on his head, his big hat. Everybody loved him and he became part of the festival family.”

“I think he was the first Caribbean act that we had,” Davis adds. “I hesitate to say that he was a trailblazer because there weren’t a lot of people following in his footsteps.”

#bahamas#blue magoos#caribbean#exuma#nina simone#okkervil river#dr. john#obeah#richie havens#rollingstone#music#spirituality

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

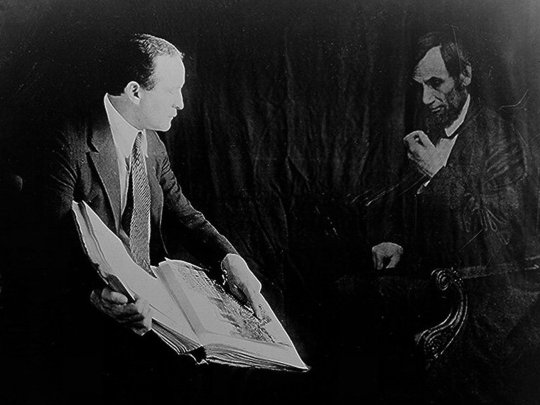

For Harry Houdini, Séances and Spiritualism Were Just an Illusion

https://sciencespies.com/history/for-harry-houdini-seances-and-spiritualism-were-just-an-illusion/

For Harry Houdini, Séances and Spiritualism Were Just an Illusion

Houdini exposed fake Spiritualist practices by having himself photographed with the “ghost” of Abraham Lincoln.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Harry Houdini was just 52 when he died on Halloween in 1926, succumbing to peritonitis caused by a ruptured appendix. Famous in life for his improbable escapes from physical constraints, the illusionist promised his wife, Bess, that—if at all possible—he would also slip the shackles of death to send her a coded message from the beyond. Over the next ten years, Bess hosted annual séances to see if the so-called Handcuff King would come through with an encore performance from the spirit world. But on Halloween 1936, she finally gave up, declaring to the world, “Houdini did not come through. … I do not believe that Houdini can come back to me, or to anyone.”

Despite Bess’ lack of success, the Houdini séance ritual persists to this day. Though visitors are banned from visiting the magician’s grave on Halloween, devotees continue to gather for the tradition elsewhere. Ever the attention-seeker in life, Houdini would be honored that admirers are still marking the anniversary of his death after 95 years. He’d likely be mortified, however, to learn that these remembrances take the form of a séance.

In the last years of his life, Houdini, who’d once displayed open curiosity about Spiritualism (a religious movement based on the belief that the dead could interact with the living), publicly inveighed against fraudulent mediums who conned grieving customers out of their money. A few months before his death, Houdini even testified before Congress in support of legislation that would have criminalized fortune-telling for hire and “any person pretending to … unite the separated” in the District of Columbia.

Harry Houdini (seated at center left) with Senator Arthur Capper (right) at a 1926 congressional hearing

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Described by the Washington Post as “uproarious,” the 1926 congressional hearings marked the culmination of Houdini’s all-consuming mission to put fake mediums out of business. At the outset, the magician stated his case plainly: “This thing they call Spiritualism, wherein a medium intercommunicates with the dead, is a fraud from start to finish.”

“[These hearings were] the apex of Houdini’s anti-Spiritualist crusade,” says David Jaher, author of The Witch of Lime Street, a 2015 book about Houdini’s yearlong campaign to expose a Boston medium as a fraud. “This [work] is what he wanted to be remembered for. He did not want to go down in history as a magician or an escape artist.”

For Houdini, a man who’d made a living suspending disbelief with skillful, innovative illusions, Spiritualist mediums transgressed both the ethos and artistry of his craft. Houdini rejected others’ claims that he himself possessed supernatural powers, preferring the label of “mysterious entertainer.” He scoffed at those who professed psychic gifts yet performed their tricks in the dark, where, as further insult to his profession, “it is not necessary for the medium to be even a clever conjurer.”

Worse still was the violation of trust, as the troubled or grief-stricken viewer never learned that the spirit manifestations were all hocus-pocus. Houdini had more respect for the highway robber, who at least had the courage to prey upon victims out in the open. In trying to expose frauds, however, the magician ran up against claims that he was infringing upon religion—a response that illuminates rising tensions in 1920s America, where people increasingly turned to science and rationalist thought to explain life’s mysteries. Involving leading figures of the era, from Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle to inventor Thomas Edison, the ramifications of this clash between science and faith can still be felt today.

Houdini (seated at left) exposes fraudulent psychics’ tricks in a 1925 demonstration.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Spiritualism’s roots lay in 1840s New York: specifically, the Hydesville home of the Fox sisters, who adroitly cracked their toe knuckles to fool their mother, then neighbors and then the world that these disembodied raps were otherworldly messages. Over the next few decades, the movement gained traction, attracting followers of all stations. During the 1860s, when many Americans turned to Spiritualism amid the devastation of the Civil War, First Lady Mary Lincoln held séances in the White House to console herself following the death of her second-youngest son, Willie, from typhoid fever. Later first ladies also consulted soothsayers. Marcia Champney, a D.C.-based clairvoyant whose livelihood was threatened by the proposed 1926 legislation, boasted both Edith Wilson and Florence Harding as clients.

Even leading scientists believed in Spiritualism. The English physicist Sir Oliver Lodge, whose work was key to the development of the radio, was one of the chief purveyors of Spiritualism in the United States. Creator of the syntonic tuner, which allows radios to tune in specific frequencies, Lodge saw séances as a way of tuning in to messages from the spirit world. Edison and Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, similarly experimented with tools for spirit transmissions, viewing them as the next natural evolution of communication technology. As Jaher says, “The idea [was] that you could connect with people across the ocean, [so] why can’t you connect across the etheric field?”

Houdini famously—and publicly—clashed with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, over the English writer’s support of Spiritualism.

Getty Images

In 1920, Houdini befriended one of Spiritualism’s most ardent supporters, Conan Doyle. A medical doctor and the creator of Holmes, the most celebrated rationalist thinker in literature, Conan Doyle was also dubbed “the St. Paul of Spiritualism.” In the writer’s company, Houdini feigned more openness to Spiritualism than he truly possessed, holding his tongue during a séance in which Conan Doyle’s wife, Jean—a medium who claimed to be skilled in automatic writing—scribbled out a five-page message supposedly from Houdini’s dearly departed mother. (The magician once wrote that the crushing loss of his mother in 1913 set him on his single-minded search for a genuine spirit medium, but some Houdini experts argue otherwise.) After the session, Houdini privately concluded that Jean was not a true medium. His Jewish mother, the wife of a rabbi, would not have drawn a cross atop each page of a message to her son.

The pair’s friendship became strained as Houdini’s private opinion of Conan Doyle’s Spiritualist beliefs morphed into a public disagreement. The men spent years waging a cold war in the press; during lecture tours; and even before Congress, where Houdini’s opinion of Conan Doyle as “one of the greatest dupes” is preserved in a hearing transcript.

While Houdini, by his own estimate, investigated hundreds of Spiritualists over a 35-year span, his participation in one investigation dominated international headlines in the years prior to his trip to Washington. In 1924, at the behest of Conan Doyle, Scientific American offered a $2,500 prize to any medium who could produce physical manifestations of spirit communications under stringent test conditions. “Scientific American was a really big deal in those days. They were sort of the ‘60 Minutes’ of their time,” says Jaher. “They were investigative journalists. They unveiled a lot of hoaxes.” The magazine formed a jury of eminent scientific men, including psychologists, physicists and mathematicians from Harvard, MIT and other top institutions. The group also counted Houdini among its members “as a guarantee to the public that none of the tricks of his trade have been practiced upon the committee.”

Medium Margery Crandon (left) undergoing one of Houdini’s (right) tests during the Scientific American investigation

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

After dismissing several contestants, the committee focused its attentions on upper-class Boston medium Margery Crandon, the wife of a Harvard-trained doctor. Her performance, if a deception, suggested a magician’s talent rivaling Houdini. While slumped in a trance, her hands controlled by others, Crandon channeled a spirit that reportedly whispered in the ears of séance sitters, pinched them, poked them, pulled their hair, floated roses under their noses, and even moved objects and furniture about the room.

The contest’s chief organizer, who Houdini criticized for being too cozy with Crandon, declined to invite the magician to the early séances, precisely because his tough scrutiny threatened to upset the symbiotic relationship between the medium and the jury. “She was very attractive and … used her sexuality to flirt with men and disarm them,” says Joe Nickell, a onetime magician and Pinkerton agency detective who has enjoyed a fabled career as a paranormal investigator. “Houdini wasn’t fooled by her tricks. … [Still], she gave Houdini a run for his money.” Fearful that Scientific American would award Crandon the prize over his insistence she was a fraud, the magician preemptively issued a 40-page pamphlet titled Houdini Exposes the Tricks Used by Boston Medium “Margery.” Ultimately, he convinced the magazine to deny Crandon the prize.

Houdini’s use of street smarts to hold America’s leading scientific authorities accountable inspired many of his followers to similarly debunk Spiritualism. Echoing Houdini’s declaration that “the more highly educated a man is along certain lines, the easier he is to dupe,” Remigius Weiss, a former Philadelphia medium and a witness supporting the illusionist at the congressional hearing, further explained the vulnerabilities of scientists’ thinking:

They have built up a sort of theory and they treasure it like the gardener with his flowers. When they come to these mediumistic séances, this theory is in their minds. … With a man like Mr. Houdini, a practical man who has ordinary common sense and science at his disposition, they cannot fool him. He is a scientist and a philosopher.

When he arrived in Washington for the congressional hearings, Houdini found a city steeped in Spiritualism. At a May 1926 hearing, Rose Mackenberg, a woman Houdini had employed to investigate and document the practices of local mediums, detailed an undercover visit to Spiritualist leader Jane B. Coates, testifying that the medium told her during a consultation that Houdini’s campaign was pointless. “Why try to fight Spiritualism when most of the senators are interested in the subject?” Coates asked. “… I know for a fact that there have been spiritual séances held at the White House with President Coolidge and his family.”

1925 magazine spread featuring Houdini exposing psychics’ tricks

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In his testimony, Houdini exhibited the skills of a litigator and a showman, treating the House caucus room to a master class on the tricks mediums employed. (“It takes a flim-flammer to catch a flim-flammer,” he told the Los Angeles Times, citing his early vaudeville years, when he’d dabbled in fake spirit communication.) He put the flared end of a long spirit trumpet to the ear of a congressman and whispered into the tube to illustrate how mediums convinced séance guests that spirits had descended in the dark. Houdini also showed legislators how messages from the beyond that mysteriously appeared on “spirit slates” could be concocted in advance, concealed from view and later revealed, all through sleight of hand.

According to Jaher, the crowd listening to Houdini’s commentary included “300 fortune tellers, spirit mediums and astrologers who came to these hearings to defend themselves. They couldn’t all fit in the room. They were hanging from the windows, sitting on the floor, they were in the corridors.” As the Evening Star reported, “The house caucus room today was thrown into turmoil for more than an hour while Harry Houdini, ‘psychic investigator,’ and scores of spiritualists, mediums, and clairvoyants had verbal and almost physical battles over his determination to push through legislation in the District prohibiting fortune-telling in any form.”

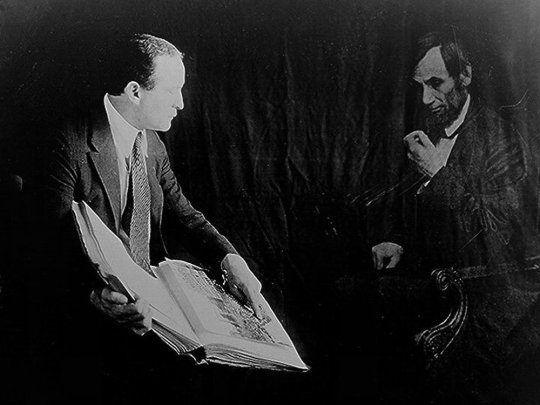

Poster advertising a Houdini lecture debunking Spiritualism

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Houdini’s monomaniacal pursuit of spirit mediums did not sit well with many. On the opening day of the hearings, Kentucky Representative Ralph Gilbert argued that “the gentleman is taking the entire matter entirely too seriously.” Others thought the magician was soliciting Congress’ participation in a witch trial. Jaher explains, “[Houdini] was trying to draw the traditional animus against witchcraft, against these heretical superstitious practices in a predominantly Christian nation, to try to promote a bill that was just a blatant kind of encroachment on First Amendment prerogatives.” Indeed, the heresy implications compelled Spiritualist Coates to say, “My religion goes back to Jesus Christ. Houdini does not know I am a Christian.” Not to be put off his brief, Houdini retorted, “Jesus was a Jew, and he did not charge $2 a visit.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, anti-Semitism repeatedly reared its head as Houdini pressed his case. During the Scientific American contest, Crandon’s husband wrote to Conan Doyle, a champion of the medium, to express his frustration with Houdini’s investigation and the fact that “this low-minded Jew has any claim on the word American.” At the hearings, witnesses and members commented on both Houdini’s Jewish faith and that of the bill’s sponsor, Representative Sol Bloom of New York. One Spiritualist testified, “Judas betrayed Christ. He was a Jew, and I want to say that this bill is being put through by two—well, you can use your opinion; I am not making an assertion.”

It takes a flim-flammer to catch a flim-flammer.

In the end, the bill on mediumship died in committee, its spirit never to reach the full congressional chamber on the other side. The die was cast early in the hearings, when members advised Houdini that the First Amendment protected Spiritualism, however fraudulent its practitioners might be. When Houdini protested that “everyone who has practiced as a medium is a fraud,” Gilbert, a former judge, countered, “I concede all that. But what is the use of us legislating about it?” As for the magician’s desire to see the law protect the public from deception, the congressman resignedly pointed to the old adage “A fool and his money are soon parted.”

Houdini died less than six months after the conclusion of the Washington hearings. He’d aroused so much antipathy among Spiritualists that some observers attributed his mysterious death to the movement’s followers. Just before delivering a series of “hammer-like blows below the belt,” an enigmatic university student who had chatted with the magician before his final show reportedly asked Houdini, “Do you believe the miracles in the Bible are true?”

The magician also received threats to his life from those implicated in his investigation of fraudulent mediums. Walter, a spirit channeled by Crandon, once said in a fit of pique that Houdini’s death would come soon. And Champney, writing under her psychic alias Madame Marcia, claimed in a magazine article penned long after the illusionist’s passing that she had told Houdini he would be dead by November when she saw him at the May hearings.

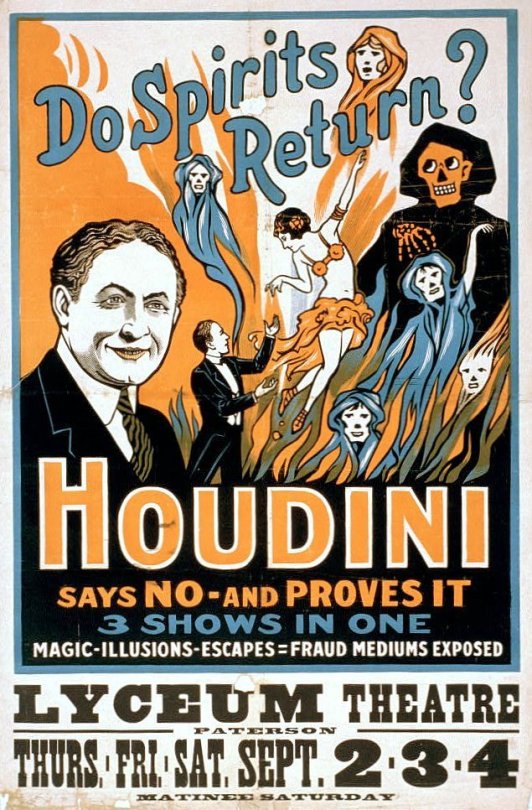

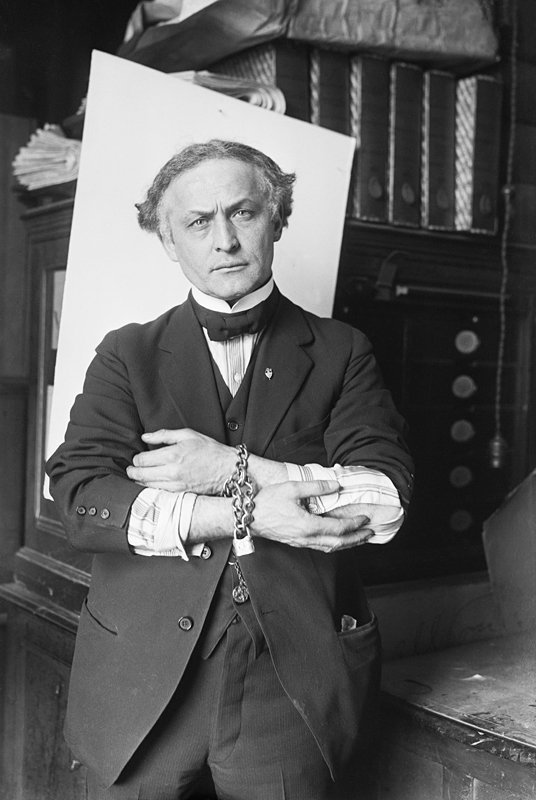

A handcuffed Houdini pictured in 1918

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Houdini failed to appreciate that Americans cherish the freedom to be duped. After all, his own contempt for mediums began with his professed hope that some might prove genuine. The fact that none did, he said (perhaps insincerely), did not rule out the possibility that true mediums existed. Houdini also took pains to point out that he believed in God and an afterlife—both propositions others might argue lack proof. As science advanced in Houdini’s time, many did not care to have their spiritual beliefs probed by scientific instruments; they did not believe it was the province of science to validate their beliefs. Theologian G.K. Chesterton, in the 1906 essay “Skepticism and Spiritualism,” said of the two disciplines, “They ought to have two different houses.” The empirical evidence science demands has no role in faith, he argued. “Modern people think the supernatural so improbable that they want to see it. I think it so probable that I leave it alone.”

Perhaps a Halloween séance can still honor Houdini’s legacy of skepticism. Nickell hosted Houdini séances for over 20 years, stopping only a few years ago. No one in attendance actually expected Houdini to materialize. Instead, the gatherings acted as “an important way to remember Houdini,” he says. “You can’t miss the irony of this world-famous magician dying on Halloween and this gimmick of seeing if you can contact his spirit, which you know he knew couldn’t be done. It was all part of a thing to make a point. The Houdini no-show. He was always going to be a no-show.”

“Unless,” Nickell adds, “somebody was fiddling with the evidence.”

American History

Art Crimes

Christianity

Congress

Crime

Death

Halloween

Judaism

Law

Magic

Religion

Religious History

Washington, D.C.

Witches

Recommended Videos

#History

0 notes

Text

Dangan Ronpa V3, Deadly Life, part 2!

Last time, we held a séance, and someone killed Tenko in the middle of it. Also, bald Monokuma turned out to be a ruse to fool us and the Kubs both, and Keebo became The Ultimate Flashlight.

So, here’s a thought. What if Tenko killed Angie? Tenko is dead, so would we have to find her killer, or would it be enough to find out she killed Angie, if that’s what happened?

Miu is bragging about having given Keebo his new light function. According to Miu, “Cunt-Fu”’s killer is either Shuichi, Himiko, Kokichi, or Kiyo. They were all in the room together when it happened. Shuichi thinks it’s unwise to rule out everyone else based on that. (He’s right. They totally could’ve gotten in from below the floorboards.

The séance was set up to lure Tenko in and kill her? Kiyo set up the séance, but he had no way of knowing that Tenko would volunteer to be the medium.

Shuichi asks Miu something strange. Does she believe that Tenko was killed during the séance? Miu says, obviously. And it’s true that Tenko was alive before the séance started, and dead by the time it concluded. Right?

So, Tenko was killed in between the candles being blown out and them being relit. Duh. What is questionable is when in that period of time she died…

Kiyo is just as worried about the fact that the séance failed as the fact that Tenko was killed.

Perhaps if they try again, but this time try to summon Tenko’s spirit instead of Angie’s? Yeah, nah. Maki has no time or patience for this séance bullshit. Just the facts, good sir.

The séance failing might be because there were six people in the room, not five. But we haven’t established that yet. What we do know is that there was a strange thunking sound during the séance, near the end of the song.

Shuichi thinks Kiyo might know something he isn’t telling us. Kiyo’s too busy worrying about the séance failing to give us any more info. Maki says the séance failed cause it was a sham to begin with.

Gonta is still crying, and Tsumugi as well. Maki tells Tsumugi to knock it off. Tears won’t bring back Tenko, or save everyone from being executed if the blackened has their way.

Himiko looks super depressed. She might not have felt the same way about Tenko as Tenko did about Himiko, but they were still good friends. Gonta tries shaking her out of her stupor, but no use. She’s still in shock, or maybe she had a mental breakdown.

Maki and Shuichi discuss the floorboards. They aren’t nailed down…they won’t come loose easily, but it’s entirely possible for the killer to have gotten into the room from there, right?

The hole near where Himiko was standing isn’t big enough for a person to get through. And in the space under the hole is…we can’t tell. We’ll investigate it after we’ve looked at everything else.

The magic circle is very far from intact. A magic circle formed with salt. Maki is skeptical as usual. Kiyo claims that he’s performed séances that worked in the past. He’s even acted as the spirit medium. Well, the circle may be ruined, but we have a copy of it in that book in Kiyo’s lab, if that’s at all important.

The white sheet and dog statue…the sheet was pretty thick, like a window curtain. Kiyo took it off of the cage, which is when we saw Tenko’s corpse.

On the back of the sheet is a bloodstain. There’s no hole in the fabric, so it would appear Tenko was not stabbed through the cloth. The killer somehow got into the cage with her, then?

As for the Dog God, it’s heavy enough that four people were needed to move it. 175 pounds. About the weight of two girls. Tenko couldn’t have escaped the cage while this thing was on it.

We put out the candles for the séance, right? How did the killer manage to kill Tenko in the darkness?

As for the cage Tenko was killed in…around 3 feet high and 5 feet wide, and made of iron. According to the ritual of the Caged Child, the ones who put the cage over the spirit medium are the ones who remove it afterwards, but Shuichi and Kokichi were still reeling in shock, and Himiko ended up being the one to take it off of Tenko’s body. I didn’t mention it at the time, but it’s weird that Himiko was able to do that. She’s so small, and it took both Shuichi and Kokichi to move the cage over in the first place.

There’s a bloodstain on the bottom of the cage. Maki questions if Tenko was really killed during the séance. Was she actually killed when the cage was lifted up? It’s a possibility, but I don’t think it’s correct. I saw that bloodstain before the white cloth was even taken off.

The only visible wound on Tenko is the stab to the back of the neck, and that does seem to be the fatal wound. If there are wounds that aren’t visible, we have no reason to suspect they are there.

Tenko was instructed not to say anything until the séance was over, but surely she wouldn’t have been able to suppress a scream as she died, right? Then again, she was very disciplined…She didn’t necessarily die instantly, but if she didn’t, she’d have bled out very quickly anyways. Maki knows from her job that when a wound is like this, the victim is almost always too shocked to do anything about it in whatever few seconds they have left. Even if Tenko had tried to escape, and even if she hadn’t been trapped by the cage, she wouldn’t have gotten far before dying.

The murder weapon doesn’t appear to be here. Which means, it’s likely not a conventional murder weapon that we’d recognize.

The floorboards near Tenko’s body look like they’re loose. As I thought.

There’s also the marker stone. It should just be a smooth rock Himiko got from the courtyard, right? Tenko had to contort her body a bit to get in the right position and fit in the cage. Could that be a clue?

Maki grabs a candle and lights it up. Together with Keebo’s light, we should be able to investigate beneath the floorboards near the hole, if we pry them loose. Underneath the center room is an entire crawlspace.

I wonder if the other two rooms have something like this? If not, whoever suggested we use the center room for the séance (Kokichi I think) is suspicious…there’s blood on the crawlspace floor and dripping from the ceiling.

There’s a hole in the wall. The blackened could have gotten under the floorboards during the séance even if the room they went into was the empty room next door. Which means that whoever killed Tenko was not already at the séance…Kokichi, Himiko, and Kiyo were the other people besides Shuichi and Tenko.

It would have been hard to do without a light, though. Then again, it would have been hard for the blackened to kill Tenko without a light too. Keebo’s light function would have alerted us to someone being under the floorboards. Maybe Miu invented a pair of night binoculars or something?

There’s a bloodstain on the floor, and a bigger bloodstain next to it. The bigger one is Tenko’s blood. The other one is dried blood, under the same floorboard, but at the opposite end. Did the blackened put the floorboard back the wrong way around? Was that the thunking noise?

There’s blood on the back of the floorboard too. And here’s something else strange. The crosspiece supporting the flooring has a part cut off. It’s near the loose floorboard, and the amount of it missing is the same as 1 individual floorboard. And it wasn’t broken, but cut, using saws from the warehouse.

In the crawlspace corner is a bloody sickle. The murder weapon? Perhaps. The blackened appears to have obtained it from Maki’s lab. So there’s three labs involved now. Angie’s, Kiyo\s, and Maki’s.

Is the sickle really the murder weapon? The blade probably couldn’t have reached her neck from below the floorboards…well, it depends on her posture. Good thing we know what that posture was.

Goodbye crawlspace. Hello, center room. Time to investigate other places. We step out into the hallway and oh what the hell is this

Kokichi’s body is lying prone on the floor, covered in blood. He’s…not actually dead, is he? No way. No fucking way.

Oh, you bastard. You fucker. You Ultimate Little Shit.

OK, but if Kokichi isn’t dead, and was just playing an incredible tonedeaf prank, where’s the blood from?

Oh fuck, the blood is real.

He investigated one of the other empty rooms, and as he stepped forward, he stepped right through a floorboard and tripped and hurt himself. Weird stutter in that description…usually Kokichi is very good at lying, though, so I have no idea what that means. Maybe it’s cause he’s injured.

Kokichi is about to pass out but Maki tells him to wait until he’s done telling them what happened.

No crosspiece? Just like under the center room. We need to investigate that. Kiyo’s Lab, Angie’s Lab, Maki’s Lab, the potential space under the two other empty rooms, maybe even the oh fuck that’s the trial bell. Nevermind.

Kokichi was also going to do more investigating before the trial. To that end, he stole the Cursed Child book…but found nothing new inside. Everything was exactly as said in the book. Kokichi goes off to go to the Shrine of Judgement, if rather unsteadily. That blood loss is not great.

Maki looks a bit nervous. Hmmm.

At the shrine, Kokichi is taunting Gonta about how he’s graduated from super idiot to just regular, Kaito level idiot. He appears to no longer be covered in blood. Neither is Kaito, (he got punched by Maki, remember?)

Kiyo says that every time Miu opens her mouth she becomes even less likeable. I’m starting to feel the same way.

Keebo is starting to have doubts about Atua protecting his chosen. But even as a robot, a being without a soul, Keebo can believe in God. And, before he even met Angie, Keebo also heard voices in his head. An inner voice, that tells him what to do whenever he’s in trouble. A conscience?

Monokuma’s trap, huh? It was to make the fourth floor scary to prevent Kaito from investigating. Uh-huh. Right. You go and believe that, buddy.

Kokichi is crying about two people he respected from the very beginning dying. Kaito tells him that crying won’t change anything. Maki points out that Kaito shouldn’t have believed Kokichi about that in the first place, because he’s a liar.

Keebo believes if he follows that inner voice inside of him, it will lead him to hope. Have I mentioned that “Keebo” is a transliteration of the Japanese word for hope?

Himiko is still unresponsive. Damn.

Down the elevator, into the courtroom. And so we begin the trial...next time!

1 note

·

View note