#have you considered that the baseline of your argument might be flawed

Note

We're upset because Izzy is the main char and they done him dirty!

if he's the main character then why's he dead 😶

#asks#anonymous#ofmd s2 spoilers#have you considered that the baseline of your argument might be flawed#that he isn't in fact the main character#that he was a tool to drive the plot forward#that his work was done?#that with the limited time they had with the season#they chose to focus on their leads - ed and stede#I'm sorry for your loss and everything but it's not the writer's fault you spent the entire hiatus assuming your guy was the lead Absbsjsjs#izcourse#<yeah this is the tag I'll be using actually

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

You were talking about some people thinking modern culture is decrepit like people who dislike the word facism and idealize the past. Why do they think modern culture is decrepit and why are some people bothered with using cultural things to describe or compare to social justice stuff? Like Harry Potter?

They often (not always, and particularly not propagandists and public figures) feel that modern culture is decrepit because they feel alienated and dissatisfied with it.

Rather than considering the actual causes of their feelings of dissatisfaction, such as a lack of close friends due to not having any free time, or a lack of energy to pursue personal interests due to extreme fatigue from work and commutes, they often conclude that the problem is actually just that society is not “as good” as it was the last time they were happy. This is often when they were a child, and thus had far fewer stresses, expectations, and awareness than they do as adults.

Some people also idealize times further back than their own life, usually because of misconceptions about what life was like in those times (most of the histories we have from even a few centuries ago, are those of the wealthy, high-born, or religiously isolated; for more recent history, most of it is written from the perspective of nationalism).

In either case, the solution is the same: a return to “traditional values” and other past aspects of culture that have fallen out of fashion.

Unfortunately for them, these kinds of changes don’t actually address the underlying causes of their dissatisfactions. So the problems aren’t solved. But they’re emotionally invested in the past being the solution, and so they often become increasingly radicalized about how people aren’t doing past-culture “correctly.”

Some people will realize this solution is flawed and come out of it better and more aware, however this is usually contingent upon having a supportive environment to grow in, because often their entire social circles have narrowed to peer-pressure environments of other worshippers of the same past. That’s why deradicalization and acceptance services are so critical! It helps people stop holding these ludicrous beliefs and instead get happy and help other people become happy. Deradicalization and recovery support--which don’t have to be provided by victims of these people, but do have to be provided by someone--are extremely efficient in removing people from these groups and undercutting the collective power of said groups.

At any rate, people idealize the past because the present is hurting them, and they want to not be hurting anymore.

Your second question, the devaluation of pop culture references to complex social justice subjects, it a little more complicated, but somewhat easier to explain.

In short, people often feel that references like that either A) make serious subjects feel frivolous, or B) make nuanced subjects more flat and shallow. But, of course, that’s all a misunderstanding of how education works. You don’t take a kindergartener and introduce them to the concept of math by doing extreme mathematics where due to some zenos paradox stuff, 2+2 is actually 3.99 repeating. You give them some little berries and say, “look, if this pile of two berries and this pile of four berries get put together, you have a pile of six berries!”

That doesn’t mean math is all about addition and berry piles. It means those are simple ways to help people develop an interest in and baseline understanding of an extremely complex field, so that they’re better equipped to understand and pursue that complexity if they so choose.

Now, one might be able to make an argument--an unevidenced one, but unfotunately the evidence simply doesn’t exist rather than disproving it--that conversation has gotten more shallow over time.

But the difference is that more people are talking about more things than ever before. In the 1950s, I wouldn’t... well actually I might not have been allowed to leave the house, I’m pretty sure mixed race kids were still illegal then. Let’s use the 80s.

In the 1980s, I wouldn’t have known what a computer is, what wireless communication is. If I wanted access to general information on an unfamiliar topic, I woudl need to phsyically go to a library and search for it. But if I had never heard of “sociology,” which I probably wouldn’t have, I would first need to hope that I saw the word in an unrelated book, and that it caught my interest enough to go looking. Realistically, I would never have known or become interested in sociology, because the knowledge was harder to access and because less people knew anything about it.

And without that, I would probably never have known there were other queers. That you can have a queered gender as well as queered sex and relationships. I would not have known those things existed, let alone how to research them, let alone how to apply them to myself.

But, because more peopel are talking about these subjects--even if most of the discussions are relatively shallow--then more people can learn they exist. And because research is so infinitely much easier now, people who know these things exist can learn more about them. And so, we have a greater population of casual understandings and shallow discussions but because of that, we have a greater population of in-depth research and theory and study and invention and progression too.

Those shallow, pop-culture laden memes about complex subjects directly create interest in deeper understandings, in people who would otherwise never have had the chance to learn at all.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rating Agency Déjà Vu

Short Shrift for Surveillance

There seems to be a scramble on at the rating agencies, but we think we’ve seen this scramble before.

Beginning late in 2006 the subprime and alt-A residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) market began its long downward slide into unimaginable losses.

The credit rating agencies – of which S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch have the leading market shares – appeared to be slow to respond. Perhaps there was good reason in the early months of 2007. Or perhaps not. An argument against promptly downgrading the RMBS was to wait for a few monthly reporting periods to validate the trend of rising mortgage delinquencies. The risk in waiting, of course, is that it suddenly becomes “too late” and you are required to implement larger, more frantic downgrades than in the alternative in which you had been downgrading incrementally if and when appropriate. But while ratings were yet to be downgraded there was no doubt, however, that the values and prospects of both the RMBS and their underlying mortgages were tumbling violently.

We’re reminded of the iconic J.P. Morgan himself who once said (paraphrase): “Every man has two reasons for doing something. There’s the reason he gives that sounds good and then there’s the real reason.”

The rating agencies had at least one “real” reason for not downgrading RMBS bonds promptly: for RMBS and other structured products, they were ill-equipped to provide the services! From our perspectives having been in the industry, reviewing Congressional testimony and materials from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, and having conferred with others playing similar roles at other agencies, we can tell you that the rating agencies did not have the capacity to methodically or efficiently oversee their models and ratings on the RMBS bonds they purported to be monitoring. There was very little that was programmatic to it. The process for the supposedly continuous, ongoing surveillance of thousands of RMBS bonds was (shockingly) manual. Or it was not done at all.

The rating agencies were much more concerned with clipping high revenue-generating new deal rating tickets, and much less concerned about providing the required surveillance on existing deals. Monies for surveillance, after all, get paid whether or not the service is provided.

So the RMBS downgrades came in waves spaced out over many months in 2007. The rating agencies placed many bonds on downgrade watch prior to the requisite modeling and analysis based on mortgage characteristics, transaction vintage, and broad market performance. This “watch period” supposedly bought the rating agencies time to perform the actual analysis before specifying actual downgrades.

Of course, while the existing ratings were intermittently “wrong” or awaiting correction, there was much ado about how to rate new deals or other existing deals that depended on those outstanding – but yet to be addressed – ratings.

Now it’s 2020 and we wonder if the ratings surveillance process has improved at all. The tremendous economic stress of the coronavirus (“COVID-19”) raises doubts of the sudden inability of homeowners to continue making mortgage payments. Many of these debtors are now unemployed with much uncertainty for the future. The house prices themselves may be greatly depressed – we won’t know until the end of this suspension period for real estate transactions. Falling home prices in 2007-2008 themselves prompted many mortgage defaults. Thus, it’s fair to say that RMBS bonds have much greater risk of default than they did at the beginning of the year.

Moody’s acknowledges the impact of the coronavirus, and the substantial uncertainty it brings with it.

“Our analysis has considered the increased uncertainty relating to the effect of the coronavirus outbreak on the US economy as well as the effects of the announced government measures which were put in place to contain the virus. We regard the coronavirus outbreak as a social risk under our ESG framework, given the substantial implications for public health and safety.”[1]

Importantly, Moody’s accepts that “It is a global health shock, which makes it extremely difficult to provide an economic assessment.” However, Moody’s is in the business of making these assessments, meaning it needs a robust and methodical way of tackling the new variable, and accounting for the uncertainty that comes with it.

The rating agencies have two very interesting vocations at present.

First, they’re actively downgrading RMBS (and most other bonds too).

Next, they’re actively rating new deals, even though some of the new deals are backed by assets that they’re simultaneously downgrading. For example, rating agencies rated five new CLO deals, backed by loans in April; meanwhile, as of early April JPMorgan was showing that loan downgrades were outpacing upgrades at a rate of 3.5-to-1.

Part 1: Ratings Downgrades

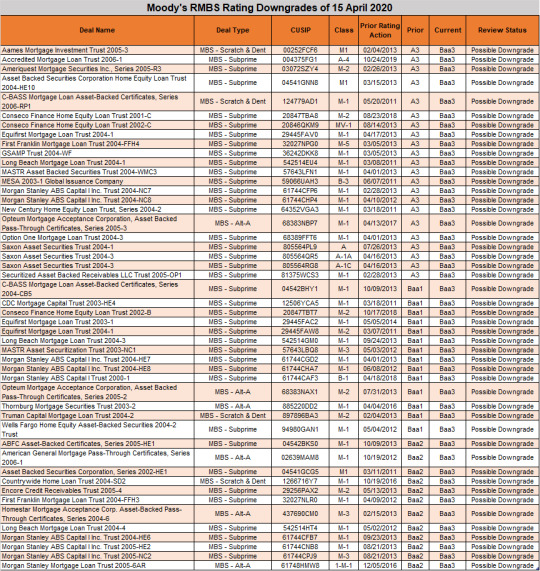

Moody’s announced, on April 15, its placement of 356 RMBS bonds on review for downgrade and the actual downgrade of 48 bonds to the Baa3 level.[2] The downgraded certificates remain on watch for further downgrade.

Placing bonds on watch for potential downgrade is not, alone, all that interesting. But the downgrades were interesting. Moody’s rationale:

“The rating action reflects the heightened risk of interest loss in light of slowing US economic activity and increased unemployment due to the coronavirus outbreak. In its analysis, Moody's considered the sensitivity of the bonds' ratings to the magnitude of projected interest shortfalls under a baseline and stressed scenarios. In addition, today's downgrade of certain bond ratings to Baa3 (sf) is due to the sensitivity of the ratings to even a single period of missed interest payment […]”

There are a few things that are interesting here.

First, the lack of specificity. Moody’s does not specify any quantitative elements of its analysis – Moody’s does not cite to changes in default rates, severity rates, recovery rates or prepayment speeds – that were adjusted to accommodate COVID-19 or that justify the downgrade action or explain the specific rating as Baa3, which is (curiously) the lowest level of investment-grade. It is all rather vague.

Second, you might have noticed some unusual language there. The “downgrade of … ratings … is due to the sensitivity of the ratings…” That is all meaningless. One does not downgrade a rating because of the sensitivity of the rating. All ratings, aside perhaps from some Aaa ratings, are “sensitive.” One downgrades because of a higher potential for default or loss, as ascertained by an analysis performed – not because of the sensitivity.

That brings us to the next issue: what analysis was performed? The short answer is, well, that there was no proper analysis performed! Aside from Moody’s failure to describe the specific analysis performed, we have at least two reasons to believe that no analysis was performed.

Moody’s does not have a methodology for incorporating the coronavirus stress: Moody’s explicitly acknowledges that the principal methodology used in these ratings was the "US RMBS Surveillance Methodology" published in February 2019, which of course was pre-COVID-19

Moody’s acknowledges that it did no modeling: “Moody's did not use any models, or loss or cash flow analysis, in its analysis. Moody's did not use any stress scenario simulations in its analysis.”

Why does it matter that Moody’s did no modeling? Because the Feb. 2019 methodology referenced is a quantitative one, and it requires extensive modeling. One simply cannot apply a quantitatively-heavy methodology while applying no models. Ergo, we suspect that Moody’s did not apply, or could not have properly applied, the Feb. 2019 methodology.

Altogether, we see 48 bonds downgraded to Baa3, absent:

an updated methodology that reflects the key new coronavirus risk, despite acknowledgment of the key importance of this risk to the deals;

a proper application of the existing methodology from Feb 2019 or any explanation as to the deviations from the methodology; and

the application of any models at all.

It is commendable to tell investors that you have not modeled cash flows, or performed any stress scenario analyses. But the questions are then: What was done and how exactly did you arrive at a Baa3 rating? What is the point of publishing a ratings methodology if you are not going to follow it, or describe specific deviations from it, so that investors can similarly follow your reasoning?

Strictly speaking and adhering to the meaning of Moody’s ratings, it is extraordinarily difficult to imagine how Moody’s could determine that 48 bonds should simultaneously earn the new, lower rating of Baa3 without analysis. With no quantitative estimate for increased loss or diminished and re-directed cash flow, how can Moody’s determine the precise new rating level?

One thought, however, is that Moody’s guessed at the rating based on the methodology, and perhaps because there were no models to apply: in the rush of rating new deals, maybe Moody’s hadn’t gotten around to building well-functioning models to replace the old ones? Or, equally plausible is the possibility that Moody’s models do not exist in the cloud, meaning that the Moody’s analysts and supervisors working from remote (home) locations could not access the necessary models, data or tools to perform their reviews. What an astounding disclosure this would be, if true, for a global data-centric organization!

Whatever the reason, the Baa3 ratings are flawed. No analysis by an outsider, or perhaps even a Moody’s insider, when applying Moody’s methodology, can credibly achieve an outcome of Baa3. It is just a guess.

Part 2: New Ratings

The rating agencies are actively downgrading bonds, loans, and credit instruments across most sectors and industries.[3] Many of these downgrades may be well-intended, due to newly introduced COVID-19-related risks. But while they are downgrading these (newly unstable) credits they are rating new structured finance credits that are supported by these very same unstable credits. Their structured finance ratings problematically look to their own ratings of the credits, which are being downgraded daily. Thus, new ratings cannot be said to be robust to the degree the rating agencies lack confidence in the sturdiness of their own underlying ratings. Moreover, the new structures are not being rated according to any new, post-coronavirus methodology. So we might expect those newly-created bonds to be similarly downgraded, too, in short order.

When S&P rated Harriman Park CLO, a new deal, on April 20th, S&P said nothing at all about coronavirus in its press release. In explaining how it came about its ratings, S&P cited only to related criteria and research from 2019 and earlier. There is no evidence that any scenario was run at all differently by S&P. No mention is made of any newly-imposed stress scenario being run.

When Fitch rated this same deal, Fitch explained its thought process and how it is deviating from its pre-existing methodologies. That’s a whole lot better than S&P in this case, but even Fitch failed to explain the “why.” Fitch simply explained what it is doing, but not why what is doing makes sense. How have they calibrated their models (if at all)? How do we know the new assumptions are adequate or comprehensive?

“Coronavirus Causing Economic Shock: Fitch has made assumptions about the spread of the coronavirus and the economic impact of related containment measures. As a base-case scenario, Fitch assumes a global recession in 1H20 driven by sharp economic contractions in major economies with a rapid spike in unemployment, followed by a recovery that begins in 3Q20 as the health crisis subsidies. As a downside (sensitivity) scenario provided in the Rating Sensitivities section, Fitch considers a more severe and prolonged period of stress with a halting recovery beginning in 2Q21.

Fitch has identified the following sectors that are most exposed to negative performance as a result of business disruptions from the coronavirus: aerospace and defense; automobiles; energy, oil and gas; gaming and leisure and entertainment; lodging and restaurants; metals and mining; retail; and transportation and distribution. The total portfolio exposure to these sectors is 9.9%. Fitch applied a common base scenario to the indicative portfolio that envisages negative rating migration by one notch (with a 'CCC-' floor), along with a 0.85 multiplier to recovery rates for all assets in these sectors. Outside these sectors, Fitch also applied a one notch downgrade for all assets with a negative outlook (with a 'CCC-' floor). Under this stress, the class A notes can withstand default rates of up to 61.8%, relative to a PCM hurdle rate of 53.9% and assuming recoveries of 40.6%.”

While it continues to rate new deals, S&P (for example) has placed roughly 9% of all its CLO ratings on watch negative since March 20th.[4]

The rating agencies suffered tremendous reputational damage when they were found to be rating new CDO deals in 2007 while they already knew they could no longer rely on the RMBS ratings supporting those deals, as they would imminently be downgraded. Once the CDO rating analysts knew the RMBS ratings were unstable and about to be downgraded, the CDO analysts were taking a legal risk in producing ratings they knew would not be robust. It can be difficult to turn away the sizable revenues that come with rating new deals – even when you do not have a sustainable ratings methodology or any conviction in the credibility of the data (including ratings) you are relying on.

The essence of formulating credit ratings for all entities (structured, corporate, municipal, etc.) requires the ability to estimate future revenues, expenses, and liabilities for a multi-year time period. Such estimates are critical to the rating process. As we write, forecasting for the broad economy and for most specific entities is highly uncertain. We do not see how it is possible to perform meaningful rating analysis amidst this uncertainty. Hence, the credit rating agencies should arguably pause all new ratings until uncertainty declines or until they develop rating methodologies that fully incorporate the wide uncertainty.

Part 3: Summary/Conclusions

Stale ratings, inflated ratings and other faulty ratings can sometimes go unnoticed during an upswing. But shortcomings become most pronounced during an economic downturn or crisis. We are concerned that we are (again) seeing the result of years of prior, weak, ratings mismanagement.

When crises occur, rating agencies should be able to swiftly update their methodologies, models and ratings. And rating agencies should stave off rating new deals until and unless they have strong and current methodologies in place to explain their new ratings and how their ratings accommodate the upheaval, whatever it may be.

Rating agencies seem quickly to have forgotten (or simply to have ignored) the lessons they should have learned from the last crisis. Regulatory settlements with the DOJ for subprime crisis-era misconduct (S&P for $1.375 billion[5], and Moody’s, in the amount of $864 million[6]) concerned issues in which they deviated from their code, which required them to provide objective, independent ratings. Those were not about the rating agencies being wrong, or failing to predict the downturn, but closer to argument that the rating agencies failed to believe their own ratings.[7]

In the above case, we would have to ask how Moody’s can be sure that Baa3 is the right rating – for all 48 bonds, across different deals, structure types and vintages – consistent with its methodology, given it failed to apply any modeling?

This article was co-written by Joe Pimbley, who consults for PF2.

https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-places-404-classes-of-legacy-US-RMBS-on-review--PR_422633

https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-places-404-classes-of-legacy-US-RMBS-on-review--PR_422633

https://ift.tt/2WH2W9I

https://www.opalesque.com/industry-updates/5969/96-reinvesting-clo-ratings-placed-on-creditwatch.html

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-and-state-partners-secure-1375-billion-settlement-sp-defrauding-investors

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-and-state-partners-secure-nearly-864-million-settlement-moody-s-arising

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-02-05/s-p-won-t-employ-first-amendment-defense-in-u-s-ratings-lawsuit

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2SgqShc

0 notes

Text

On the Persona 5 translation

I’ve read a lot of extremely hot takes on the Persona 5 translation today. So many, in fact, that it’s difficult to address everything wholesale. To the their credits, the critics are both thorough & well-articulated, and their arguments are strong enough to get me thinking - strong enough, even, to kickstart me pushing out this writing blog I’ve been wanting to get off the ground.

I want to respond to the myriad of issues listed on the website being currently used as a sort of rallying-cry, http://www.personaproblems.com/ . It’s well-designed, and organizes the issues well. I’ll start at the top, then:

- “Yet no other form of media would ever get away with the number of errors found in Persona 5's English script.”

This is a very minor nitpick, but actually, yes. Other forms of media would, indeed, get away with any number of similar errors; viewers of foreign films, for instance, can tell you all about how perfect-world this sentiment is. Additionally, classic books aren’t retranslated for no reason; direct translation is not actually a Thing, and any translated work is going to display the biases, quirks, and language tendencies of its writer(s). This is why people learn dead or archaic languages just to read Cicero or Plato in the original text. It’s a bizarre claim, to say grammar issues are not a problem throughout other media. (Also, try reading a novel translated from a Slavic language, if you don’t like stiff dialog. Have fun.)

- “The baseline for any translation is this: readers of the translation should receive the same experience as readers of the original, as if the original creators had written it natively in both languages.“

If this is the writer’s goal when they go about their own work, it’s admirable. It’s also completely impossible. What does a “native” English speaker sound like? Are they American? British? Australian? Here’s the short of it: by translating a work in your own native tongue, you are co-authoring the piece. It is never, ever, going to be a 1:1 situation when facing down the realities of character limits, cultural differences, & even personal backgrounds. Some works get closer, some works get further, and it’s down to the writers to decide whether a strict or a loose translation better fits the text.

To a certain degree, the way we think - the actual way we formulate & process our thoughts - is influenced by language itself. If you ever communicate with folks who speak English as a second, third, fourth, or so on language - you’ll notice that, even when extremely proficient, they don’t just totally entirely lose the speech quirks that come with their parent language. Eliminating those quirks of speech already changes the context of the work. Is this a bad thing? No, not necessarily; but it’s presumptuous at best to believe yourself capable of understanding how another person would write “if only they were native” in your language.

- “Translation can be a murky concept, so first I'll define a standard to measure against: imagine if translation weren't necessary at all.”

I absolutely despise this. The assumption made is that any story could be told completely, and just as enjoyably, in any language, in any culture, without any change to structure. It is simply not how language works.

- “Translators do not convert words from one language to another: they convert ideas.”

Okay. Let’s keep this in mind.

- The entire “Why aren’t more people complaining?” section

This is one of the most bizarre, difficult-to-follow explanations I have ever seen. It makes totally weird assertions, such as the idea that people hold early, loose translations against current-day translators. That’s a really strange idea, considering the popularity of things like NA Kefka, or bounty-hunter-Samus. The truth is that if the translation was good back in the 90s, no one cared if it was inaccurate. Outside of Usenet, none of us really had a point of reference. The writer seems to have some sort of personal beef with Working Designs leaving Bill Clinton jokes in their work, or something. I am especially confused by the TV Tropes links here, and what they have to do with the point.

Cutting down on this section, we could just apply Occam’s razor: most people have no issue with the translation.

- I’m not going to go through all the examples. There are some I think are silly, some that I haven’t seen yet, some that are definitely awkward.

One thing that does frustrate me about these examples - it’s noted by the writer that the script does a fine job of getting _the idea_ across. There are few, if really any, examples of the game actually failing to convey meaning. By the author’s own definition of what a translator does, the script succeeds. No, it doesn’t flow the way it would if it were written by an American. Translate dialog this way, and it sounds weird for English speakers elsewhere in the world. It’s a give and take - we don’t all speak the same English. “But these are factual errors!” is a really silly argument here; if they are, why isn’t this an issue for everybody?

- “Unfortunately, while it's possible for a translation to be stiff but understandable, stiff but accurate translations are pretty much a myth.”

I hate this idea, too. “If it doesn’t sound right in American English, it’s incorrect, & doesn’t get the idea across.” The other thing I really don’t like about this is the vast majority of dialog in Persona 5 flows very smoothly for native English speakers! The writer even seems to be aware of that fact, as I’ll address later.

- “It's definitely great to get to experience the cultural aspect of a piece of foreign writing. However, that foreign nature should be expressed by the text's content, not by the text's awkwardness. This goes back to creator intent. If the original creator were perfectly fluent in English, would they have made their writing intentionally awkward just so readers could feel how “foreign” it is?”

I really fucking hate this! How are you ‘expressing’ the cultural aspect of a text by eliminating the speech quirks of the parent language - is the implication that you intentionally add lines to express the character’s nationality? It really feels like ‘thing that detracts from my experience by taking me out of my personal cultural & linguistic comfort zone should be removed and replaced with, y’know, something.’ And that final claim! People who write in two languages - or speak fluently two languages - will very, very often include quirks, stiffness, or other eccentricities in their own personal English. If the author means “fluent in the brand of English I speak and write,” that’s extremely irritating!

- “Consider—how would readers react if George R. R. Martin released his next book and every third sentence was awkward, with every fifth sentence containing an objective error? Writing is hard, and his novels are long, after all.“

I wish this author had simply not written this blurb, I was so much warmer on the criticism beforehand. George R. R. Martin works in an entirely different medium, in one language, with years and years between each published work. The criticisms even this writer has with Persona 5 do not extend to “every third sentence,” “with every fifth sentence” containing some sort of grand, inexcusable error. People would be far, far more upset if this were actually the case. This comparison fails in every conceivable way, & is just outright ignorant.

- “One reason someone might use this defense is that they genuinely don't see a problem, because to them those flaws aren't flaws. And that's valid, so long as they accept other people's right to believe otherwise.”

I like this. I wish the author didn’t hide this at the end, behind all of the assertions of objective “failure” and “outright errors.”

- “I haven't listed every mistake in Persona 5, or even a substantial fraction of them. I've also been forced to focus on the translation aspect of localization, which means I haven't properly addressed other failings such as bad typography, untranslated images and video, and voiced lines that are unsubbed even when Japanese audio is enabled.1 Nor have I dedicated time to the sometimes strange handling of honorifics.“

The typography complaint is valid, though one of the pettiest things I’ve seen in awhile now, and the untranslated images are a series staple, but the honorifics thing HAS bothered me since P3. Just commit or don’t, guys.. Anyway, not much to say about this chunk. I just wanted to say, man that honorifics stuff can be weird (& has been for years).

Listen: If you take nothing else from this write up, understand that I have no issue with people disliking the P5 translation. That’s totally fine. My problem is with the concept of there existing a ‘correct’ English, or a ‘correct’ translation. My problem is with the repeated emphasis this writer, and others expanding on them, place on their definition of “objective” errors. The vast majority of the moments picked out by this writer are not selections of terrible grammatical errors - and I’d argue that it’s /completely fine/ for a couple of those to exist in a fucking video game - but of what the author calls stiff language. That is to say: Neither meaning nor soul are impaired by the P5 translation.

The reverence with which this author refers to the text - referencing how the translation has ruined one of the ‘greatest RPGs of the last ten years’ for them, and so on, so forth - speaks to a kind of pedestal-hoisting that does no good for anyone. For example, in the Sae moment detailed on the site from the start of the game, with the “psychic detective”; what makes the original so good? In Japanese, the detective says “There’s been a call for you” right before she receives a call on her cell phone. Is this not silly as all fuck? Why is it so much better? Why did Sae’s boss call the detective first, why didn’t he just call her cell phone if he had it the whole time? The English script changes the moment to make the detective seem aware that she’s about to receive the call - emphasizing that the detective and Sae’s boss are working together no one in the scene can be trusted, while also positing Sae as an outsider. Watch the scene again and see if you get what I’m saying. https://youtu.be/f3bVM2mxh4k?t=876

It’s super frustrating that a changes like this get flak from this writer, while the worldview being pushed is one of ‘capturing the spirit, not the words.’ It’s also frustrating that many of the game’s legitimate, real problems (that aren’t fucking, the font used to spell out ‘hello’ on a calculator, god damn guys it’s okay most people have done that before) are ignored - such as the constant battle chatter every time you hit a weakpoint in a game centered on repeatedly exploiting weaknesses, or the intensity of the writing game’s first chapter. The writing is held in extremely high regard, & the translation is being used to try to assert the truth of controversial axioms without actually needing to discuss said assumed “truths.”

I just want to leave with one assertion: There is no “correct” English. It’s okay for a text to sound awkward (especially in visual media) _with the caveat_ that it must get the spirit of the original work across. It’s all right, for sure, for a foreign text to challenge or disrupt the expectations of a native English speaker in its translation. In some ways (and not even all), Persona 5′s translation does this. Is it a perfect translation? No, no translation is. Do you have to like it? No. Should you respect the opinion of players who do (as well as ESL players & those abroad!) enough to avoid making sweeping, generalized statements about the failure of the script to appeal to your individual sensibilities, complete with long, detailed theories as to why other people don’t seem to mind? Please. _Please_. Honestly, y’all make this game sound like it’s Chaos Wars, or Arc Rise Fantasia. The hyperbole is unreal, and it simply needs to stop.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Regarding the Gentle Art of the Passive Check

Raise your hand, if your Dungeons & Dragons character is supposed to be a master of ancient magics, or whatever, but can’t ever seem to accomplish any test of intellectual and arcane skill, because you, the player, keep rolling 2′s on your d20? Go ahead and raise your hand, and really confuse the people around you, in the coffee shop.

Now, raise your hand, if you’ve ever DM’d games of Dungeons & Dragons, where the heroes enter a room with secrets to be discovered, and when you ask the players to make a Perception check, they respond by obsessively searching for the things which they aren’t supposed to know are there.

These are well-known dilemmas for anyone experienced in playing roleplaying games, and Dungeons & Dragons has answers, but is extremely vague about them, because they want to empower DMs to make their own decisions about things that they don’t understand. Said answers are Passive Checks: when the DM evaluates the result of a character’s effort, without rolling the die, and instead using the equation of 10 + Skill Modifier.

The Player’s Handbook is sparse on the details, and the Dungeon Masters Guide even sparser, but the essence is any of a handful of mechanics:

1) when the DM wants to test the player characters ability to accomplish something, without letting the players know about it, the DM may use a passive check (A.K.A. seeeeecret check).

2) when the narrative situation is such that DM would be asking the player to make many consecutive ability checks, the DM may, instead, use a passive check (A.K.A. make one average check, so you don’t have to make a full-days’ worth of regular checks).

The second mechanic is pretty harmless and makes a lot of sense, but the question of whether checks should be made in secret has a range of fans and detractors, depending on how much the DM trusts (or wants to trust) their players to not meta-game, or how much the DM wants to create a sense of drama in their game.

3) There is, however, a more interesting issue, in a 3rd mechanic, which is *not* in the core rulebooks, but has been described by Jeremy Crawford, lead writer for the Player’s Handbook, as the intended mechanic: that the value for a Passive Check is intended to serve as a minimum value for a regular check, at least for Wisdom (Perception) checks. The idea is, that there is a baseline level of awareness, which is available to the character when they’re not paying particular attention; it’s the difference between spotting something which you’re looking for, and just happening to notice it. (take a gander at this podcast episode, for more details about this concept: http://dnd.wizards.com/articles/features/james-haeck-dd-writing)

This leads us to the fascinating question, of whether it makes sense for a character to have a minimum-possible value for any check, if they have one for a Perception check? Maybe the wilderness-guide ranger should be able to get a sense of direction or danger intuitively as well as analytically. Perhaps the worldly bard should be able to sniff out a liar before they even speak, without having to take in their cadence and micro-expressions. In other words, maybe sometimes you just get a feeling about something.

ALSO, though, this mechanic doesn’t have to assume that the character isn’t paying literal attention; instead of it being “oh, I didn’t realize that I was attempting a feat of Acrobatics,” perhaps it can be “this feat of Acrobatics? No sweat; I don’t even need to try.”

This is a SUPER-contentious item amongst the dungeon master community, since it boils down to pure philosophy of gaming. Shouldn’t skilled characters be able to consistently succeed at their skills, even if their player can’t roll to save their imaginary life? ...but shouldn’t characters also be able to fail catastrophically? Shouldn’t players be better than meta-gaming, and shouldn’t the DM trust them to be? As I often do, I believe that the real answer is revealed with MATH!

Looking at the numbers, characters with a +0 to a skill will automatically succeed at a DC 10 check; we’re talking about a character being able to walk through Very Easy and Easy skill checks, and the DM gives it to them automatically, even if they aren’t particularly good at that skill. ...unless a character has a penalty to that skill, in which case their passive score is probably 9, maybe 8. Keep in mind, that, we’re talking about Very Easy and Easy checks—mundane tasks; things that anyone could do, and the only questions might be how well they do it, or how long it takes. It could be something as minute as opening an unlocked door, or something as neutral as chopping firewood, where a skilled person can do it magnificently, but a complete derp can still accomplish it.

(conversely, a check with a DC of 15 almost always requires a character to be proficient in that skill, to pass it with a Passive Check. The keyword, here, is ‘proficient’ -- a character needs to be actually good at this thing, for the DM to just give it to them, and this is for a check which is considered to be only Moderately Difficult.)

...and that’s the part that I think most people miss, thinking about Passive Checks -- EVERY DM hands out automatic successes for most things that a character does. DMs don’t require a die roll, for a character to open an unlocked door. It’s something extremely easy, the DM says “yeah, you can do that,” without going to the d20. ...and, why would they? That’s a task that’s well-within that character’s ability to accomplish perfectly-well, nearly every time. This DM just used a Passive Check, against a task with a really low DC. The big variable in every DM’s usage is how extreme is the ease of the task which is being attempted. Of course a DM wouldn’t require a roll for opening an unlocked door, and of course they would require a roll for picking a locked one. It’s the stuff in the middle that’s the question -- the checks with a DC of 10, 12, 15, which are the question, and Passive Checks simply offer a consistent mechanic answering that question. Would the scholarly wizard be able to find common information in a book? Probably. How about the barbarian? Maybe not. On the flippy side, a check which isn’t a gimme is not going to be accomplished passively, except by a character who’s reeeeally good at that thing. So, is it a given, that the barbarian could make the 5-foot jump over a pit (let’s say it’s Athletics, DC 12)? Almost certainly. ...but the wizard? Not at all. This is a mechanic that provides quantifiable justification to answer the question of when to grant an automatic success, or when to require a roll -- something that every DM has to think about, throughout every game.

Personally, I prefer a somewhat middle road for Passive Checks. My guidelines are:

For Passive Check Mechanic #1: Seeeeeecret checks,

Does it make any damn sense for the skill to have a sub-conscious baseline level of that skill? When making this check, the question is literally whether the character is aware of needing to use this skill, and if they could just happen to notice something, or get a feeling about something. So, physical skills probably don’t make sense, here, ie., Athletics, Acrobatics.

I use Perception, Insight, Survival, Medicine. ...Wisdom skills, basically, for that gut-feeling factor. I can see an occasional use case for Charisma skills, for those situations the character’s vibe is affecting a whole room, and the character hasn’t taken particular notice of every person there.

Is the situation such that a sub-conscious baseline level of that skill would be available to the character? Sure, a character keeping watch over a quiet campsite could happen to notice a hidden monster, but what about in the heat of battle? Other roleplaying games (see: Kids on Bikes) have standardized this distinction as a primary mechanic in their system, distinguishing decisions or actions made in calm situations versus stressed situations, and, if you want to allow Passive Scores to ever be used in these situations, D&D can handle this with Advantage and Disadvantage (which modify a Passive Score by +/- 5).

For Passive Check Mechanic #2: Make one check instead of a billion,

Will the character be doing this thing repeatedly for more than 6 seconds? This one is useful for a whole day of library research, or hours spent climbing a mountain, crawling a dungeon with constant searching, or anything that takes a while; more than a minute, even. Its flaw is that it does assume the law of averages -- that the character will never achieve an extraordinarily good or bad result. That don’t seem right to me, so I think it makes sense to ask the player for a roll, first, to give them that chance to roll really well, or reeeeeally badly. Then, if they didn’t roll a 1, the Passive Score can be their result.

For Passive Check Mechanic #3: Passive Score as mimimum-possible-value for an Ability Check,

Is the DC for the check below 10? It’s in the every-day, low-difficulty tasks, where a character really should be able to perform how we expect them to, since they have the time and room to set up for it. Probably less so, for the more difficult tasks, although there is an argument for pressure actually sharpening one’s senses, which is totally a thing in real life. How to measure if a character is a pressure performer? Imagine me shrugging. (if it helps, I’m 5′7″, average build, with brown hair and eyes, and a short beard)

Is the situation such that the player would ask to make the same roll over and over again? You can’t just keep rolling until you get a 20, but if the character has the time and the freedom to keep trying something, they truly should get something more than just that one roll. Then, the situation falls under the purview of Passive Check Mechanic #2, so just use the Passive Score to back up a single roll.

As contentious an issue as this mechanic is, I believe that it’s really just a sensible way to codify the long-standing common-sense practice of allowing characters to auto-succeed certain tasks, and lets skilled characters be skilled.

0 notes