#i thought we agreed with the obvious level one media literacy thing that we could think a thing is good but also flawed. everythings

Text

elemental has turned around at the box office and gone from flop to doing well. it seems this is pretty much entirely because of word of mouth. maybe theres other factors im not considering, but thats pretty fucking impressive.

and i think it deserves it tbh. it is far from perfect, but it might be my favorite pixar film of the 20s so far. granted, the bar isn't as high as the 10s or 00s, but hey, the decade is young. its pretty good!

i think what i liked about it was mainly that it was really emotionally sincere. like. its not too snide or self-aware, it just deeply cares about its characters and is totally committed to the world.

so many newer pixar flicks have this "popcorn filler" middle where there's zany antics that barely connect to the emotional journey. this movie doesn't. its all about these two main characters bonding in a way i found organic and compelling. and there's very little cringe humor. that one annoying tree guy is basically just in it for two seconds. idk why disney marketing still (wrongly) believes that kind of eyebrow wiggle humor is popular, because that made the movie look WAY worse.

anyway. its definitely good for a movie that was written off en-masse as cringey and generic and a lazy race metaphor. i don't think its any of these things. i think the main creative voice speaking about their own immigrant experiences does the job in a decent way.

also, that one clip of "fire girl being racist" is ignoring the crucial context that SHES the immigrant whos discriminated against, not some white-coded karen who needs to learn to be less racist. shes aware that shes less privileged and doesnt want to rock the boat.

also-also, i'm not even going reason with the badfaith twitter take that "she doesn't wanna date the tree boy because she's RACIST instead of it being because he's a CHILD?? #groomer alert!1!!"

like. come on. she's clearly not interested in him, she doesn't need to Spell Out that its because he's a child. that's not the point of the movie. thats just the most lazy twitter hot take for the sake of morally justifying that you found a thing cringe. don't be that person.

if you don't wanna see it, hey, don't. its fine. i'm not gonna go to bat like its the most important movie ever or anything... but its nice seeing pixar have more well-rounded, developed girl characters, after decades of being the emotionally sincere boys club. about time.

also, the romance is cute. i totally get why the aroace community in particular relate. like. its a romance where they Literally cannot touch each other, so its a relationship that actually develops because of their personalities rather than anything physical. its nice :)

#elemental#elemental 2023#not su /#animation#pixar#disney#there are points against it i agree with related to character design and body types (and marketing)#but idk man every main character in fucking atla is skinny#i thought we agreed with the obvious level one media literacy thing that we could think a thing is good but also flawed. everythings#flawed in some way obviously - but i also understand the specific issue here. but its not unique to this film in any way

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Text: Tell me, what do you think of people actually liking the character development in season 4-5 and the show's treatment of mental health? [Redacted] thinks that and she's the mother of a teenager]

Re liking the show: I generally assume that they have poor taste and/or media literacy.

Re the mental health rep: I generally assume that they're incredibly privileged and/or ignorant.

I'm posting this as an image and not an ask response specifically because I will not participate in fandom drama or shaming. This blog exists specifically so that people can actively choose to engage in my content and so that I can post critical thoughts without dragging their source into some petty fight. So I'm not going to talk about the named individual. Instead, I'll replace them with the show's head writer and talk about him in a similar context.*

He's pretty famously denied that Chloe suffered any abuse, ignoring her obvious neglect, which came from both parents, just in different forms. When you pair that with how the show handles people like Gabe and Jagged Stone, we see a clear pattern of the show ignoring the devastating effects that abandonment and neglect can have on a person, especially if they're a child.

Now you could look at that and say, "The head writer condones abuse! He's a monster!" But I prefer to go the more likely route and assume that he's a privileged middle-class cis white man who has never had to deal with those issues or support someone who has, so he has no idea how to handle them properly or that they even need to be properly handled. There's every chance that he's a loving, kind man and a fantastic father who just happens to not be very good at writing a complex topic that he clearly has no understanding of or desire to learn about. I apply similar logic to fans who share his opinions. Never attribute to malice what can be explained by incompetence or ignorance.

And all of the above is assuming that we're talking about someone who thinks that the show is objectively good or that the mental health rep is good, which are big assumptions. It's fully possible to enjoy a piece of media that you know is objectively bad or even "problematic" in some way.

Personal confession time: is Loonatics Unleashed an objectively terrible show that you should never, ever watch? Absolutely. 100%. Are Rev Runner and Tech E. Coyote two of my favorite characters who will live rent free in my head until the day I die? Yep! I pulled up a YouTube highlight real as I was writing this and those dorks still make me smile even though the show is terrible on multiple levels and I know that I'm not alone in that sentiment. Those two clicked with a lot of people for some reason.

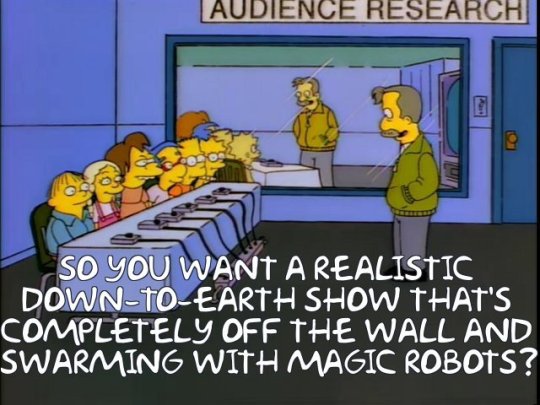

A piece of fiction need not be good for you to love it and you don't need to justify your love for a piece of fiction if you're not claiming that it's good. Similarly, people hating that piece of fiction or pointing out flaws in it is not a reflection on you in any way shape or form. You can even agree with their criticism and still love the piece of fiction. This approach to media - loving a thing in spite of its flaws - is normal and healthy and I'd really love to see it make a comeback in younger fandoms.

Like, I cannot emphasize this enough, most fandoms consider it perfectly normal to have lots of fans who are critical of the source or who have even lost interest in the source for one reason or another, but they still like some element of the source enough to want to create/consume fan content for it. These more critical fans arguably make some of the best fan content because looking at canon and saying "That's nice, let me show you how I'd do it" often leads to some of the most complex stories that you'll see in fandom spaces. Stories that can often blow canon out of the water for TV shows and movies since fanfic isn't limited by budgets or studio policies or marketability concerns. Fans who think that the source is perfect tend to just write fluff or romcom type fics, which is not a dig! I love bother of those genres! But woman does not live on fluff alone.

Obviously there's some complexity here because who decides if a show is bad? Saying "it's okay that you like a terrible thing" can certainly sound like an insult and prompt a feeling of needing to defend the thing, which is why I don't fight with fans who like the show. There's really no need to convince them that the thing they like is bad. Do I think it is? Yes. Does it matter if they disagree? No, not really. At worst, they create stories with similar issues and, well, they're not the only ones and fighting with them isn't going to stop them. You're much better off focusing on creating your own good media and trying to get that popular. Heck, even if you made the head writer see all of Miracuous' flaws, it wouldn't change anything. The show is already made.

So, yeah, I don't really assume anything bad about people who think that miraculous is good. I know lots of wonderful people who have terrible taste in media and I'm still friends with them. I just don't take recommendations from them.

It's important to remember that, when you're online in a fandom space, a person is condensed down to a very tiny snapshot of who they are and judging a person solely off of their thoughts regarding a poorly written kids show is a dangerous path to tread. Like, looking at this blog, you might assume that I spend all of my time thinking about miraculous and obsessing over its flaws, which is very much not the case. I actually have this blog specifically so that I don't obsess over miraculous' flaws because I've found that, when something is bothering me, writing it down or talking to someone about it is the best way to stop thinking about it. Even then, most of my posts are reblogs of stuff I come across while browsing my tumblr feed, which is not solely miraculous content. I mostly interact with the show by creating non-salty fanfic that I honestly enjoy writing and find to be a relaxing, positive outlet.

It's human nature to judge and it's totally normal to think that a person's an idiot because of something they post online, but be careful to not lean into those thoughts too hard. At the end of the day, Miraculous is just a stupid kids show that will fade from the popular consciousness a few years after it stops airing. If it and/or the fandom are negatively affecting your mental health, then it's okay to step away for a while or use the block button. It really is your best friend. I enjoy being critical about Miraculous specifically because it's not that important. While I do think that kids deserve better media, I don't think Miraculous is some terrible evil harming the youth. I'm not horrified when a kid watches it, it's just not a show that I'd encourage them to watch and, if the kids was close to me, we'd spend a lot of time talking about the bad things that the show showcases from time to time. There are lots of episodes that are fine and I can think of way worse kids shows. Shows that tell their horrifying morals really well, making a kid far more likely to pick up on them and internalize them.

*Note that I only feel comfortable talking about the head writer like this because he's a public figure with an active social media presence AND because I'm not @ing him. If he was a private person or if he was not a professional creator, then I would not talk about him like this and even in that context I try to avoid it whenever I can. You can think that he's a terrible writer, but he's still a human being and, as far as I'm aware, nothing he's done deserves people harassing him.

I absolutely understand how devastating it can be to see a story you love get ruined by the creative team. The first time that happened to me, the life lesson I came away with was, "I will no longer put my happiness in the hands of another creator. I will enjoy stories, but I will temper my expectations and remember that they're just another human being and it's completely possible that their vision for this seemingly awesome story may end up being terrible."

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

What if they knew what they needed, too?

I just finished A School of Our Own, a strange, frustrating, and provocative book about a "school within a school" founded by a precocious 16-year-old, the son of an education and development theorist.

It's strange because the co-author (the mother) cedes well over half of the book to the articulate but nonetheless unpolished journals and reflections of her son as he went through the process. It reads like a whip-smart 16-year-old kept a detailed journal and shaped it together in grad school, which I imagine is something like how it happened in real life.

It's frustrating because the nature of the program was so tiny (8 students, at least one of them personal friends of the author) and the duration so short (six months) and the circumstances so unique (the program seemed to be largely led by the author himself, with some support from his peers, and with little faculty intervention save mentoring roles) that it hardly seems replicable in its particular incarnation, let alone scalable.

But what was fascinating about it was that the central premise of the book, the big "so what" of it to my mind, had nothing to do with any of those seemingly obvious flaws of the book and of the program, and it's something I've been returning to a lot as I enter my third year teaching at an alternative high school:

What if students not only knew what they wanted, but also knew what they needed from school, too?

The first premise -- that students know what they want -- is hardly uncontroversial. Still, in most progressive education, this idea, whether it involves following interests, developing unique projects with broad parameters, following one's educational muse, so to speak, this general idea that students should know what they want and "what I want" should be incorporated into the school day is fairly well accepted in various forms. Media literacy education places much of the engagement in digital media and popular culture; critical literacies connect social justice to one's place in one's community and in the world; expeditionary learning assumes ownership in mastery, and on and on.

But none of these progressive approaches, as far as I can tell, truly cross the rubicon to the second proposition, that students know what they need from school. If they knew what they needed, after all, a name for their program would be unnecessary. The students would just do it themselves. Indeed, the oddly provisional title of the school in A School of Our Own -- the Independent Project -- seems almost pathologically neutral in expressing any of its radical potential.

In the car a few weeks ago, my wife asked me, "what would you do if you could open your own school?" And after thinking for a few minutes, since I'd never really thought about this so directly before, I answered, "I'd ask the kids what they wanted and I would trust what they told me."

Then we had a conversation about what my wife wanted in high school, and whether what she wanted synced up with what she valued in education after high school. It was -- she would have jettisoned classes she hated, tried out more classes on a trial basis to see whether she might like them (this was how she found the one science course that resonated with her -- auditing a class she didn't need and taking it anyway), spending more time reading and less time doing things she found boring.

But even in this conversation, my wife was quick to point out that she didn't think that would work for "everybody." The idea here is that of course the most capable students could map out educational outcomes for themselves, but they had the support and perhaps the natural inclination to do this, and other people need more structure, more of a predetermined path.

Oddly, my experiences teaching with students who have been systematically shut out of educational opportunities has suggested almost exactly the opposite. What seems truer, to me, is simply that these students have a different way of thinking about education and about their own lives that seems foreign to the kinds of students who might have designed an Independent Project that looks like the one in the book (my wife's would have been nearly identical, in fact). And this is the great disconnect in what it means to design a school for students who don't seem to benefit from the structures and privileges of relative affluence -- that is, a fully functioning and even thriving school system at the most material level, if not at a pedagogical level: just because my students want dramatically different things from what's being offered to them doesn't mean they're wrong, or that it's not what they need.

I had my students design a school of their own on the first day (we enroll new students every ten weeks). Amid the traditional schools that simply operated more smoothly and had better food and later starting times (a universal request -- pay attention!), there were schools that were far more vocationally based, schools that taught students how to roll a proper joint and had marijuana dispensaries on campus, schools that turned all math into financial planning classes*. Schools that were something like community schools, whose primary purpose was to provide child care and job training opportunities. Schools where college professors had to come and give special lessons for shared community college credit.

All of these are ideas that currently exist, at least in pieces, but when my students designed the schools, their priorities didn't assume there were also these other things that experts could bring in that were outside of their current understandings and experiences that would somehow elevate them beyond their current imagination. They didn't assume that many of the goals of current progressive and other alternative educational models were ones that they should care about, or that they should consult with an education expert, say, to find out. It didn't occur to them, and the radical element of trusting students here would be to accept that some outside idea wouldn't necessarily provide any real benefit to their design.

But I think it's instructive for people who design educational experiences to do a thought exercise where you ask the students you work with what they want, and to immediately translate that into what they need. It may not work -- and there are signs that the Independent Project itself was relatively unsuccessful after its charismatic founder left the school -- but I've found that it's helped to change my mindset around what education is at some basic level. It was a good way to tap-dance around a post on political horizons for education that I’ve been mulling over for months now.

*There's a somewhat remarkable post-script in A School of Our Own, under the heading "Math," where the authors admit that they screwed math up, and that through this experience they came to the belief that math is much less necessary to high school education than they assumed going in. They express the belief that math is too specialized to be particularly useful in any broadly interest-based curriculum designed by students, and that it's essentially a waste of time to teach discrete math concepts disconnected from other subjects. I don't know if I agree with this, but having now taught math as a kind of all-purpose academic support teacher for a few months, there is something deeply wrong with math and math teaching. More on that later, maybe.

4 notes

·

View notes