#is blatantly about how capitalism destroys lives and communities

Text

Next person to call night in the woods a cozy game gets thrown off a cliff

#the game is literally about a cult that murders young adults they think arent productive enough#is blatantly about how capitalism destroys lives and communities#and is also about depression and how being in ur early 20s kinda sucks#just because it takes place in the fall and doesnt have combat doesnt make it a cozy game!!!!#im losing my mind#night in the woods#nitw

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

While I'm posting about my pathologic transcription, I'll make shorter posts about my takeaways. About the literal health of the environment around town, we get a couple people on day one to give context. The most obvious is Aspity, but to get an idea as to why things are as she says, you have to talk to a drunkard, called a Carouser, and a Tot.

The Tot mentions a "Rotten Field," and when asked what that is, he says:

"It’s where they bury the bulls’ bones. The place is covered with fur instead of grass, and it’s all bones bones bones underground. Bones and horns. Yeah."

Why are so many bones and horns and hides being thrown into a field instead of being used in some way? Either for jewelry, clothes, or for tradesmen's tools, these things have a variety of uses.

The Carouser, when asked about the Abattoir, says:

"Hundreds of bulls are being slaughtered there- what else is there to know? It is our humble town that provides the whole Northeastern region with beef! Or even the whole country mayhap."

It's because of the massive scale of the Bull Project that so much excess material is being produced and then thrown into the fields and rivers as waste products. Nothing is in higher demand than meat, nothing is needed as regularly, and perhaps the people in the Capital and in other towns are less interested in buying blood or bone. It's not profitable, the Olgimskys don't view it as anything but by products of more lucrative things.

Aspity says:

"All that water comes from the Steppe and it isn’t exactly clean. Yesterday I inspected all the springs in the area; there seems to be no more clean water around. That salty taste is everywhere, it’s reddish in colour, and there are disgusting clots in it."

And when Bachelor asks for more information, she says:

"The towsnfolk store water in home-made reservoirs. This modest supply should be enough to help us last a little while, but afterwards we’ll have to drink that bloody mixture."

Bachelor reacts to this with disgust, and can even insist she is lying, perhaps because he had been benefitting from this disgusting reality in his life in the Capital.

Aspity's whole point in starting this conversation is to make blatantly clear some of the side effects of the Steppe's occupation, which is that the waste material of the Abattoir is dumped into the river and land. This problem would be lessened in severity if the community was manufacturing meat not for the sake of providing for the entire country, but just for the local population and what's necessary to export in exchange for other essential imports. Obviously, this would be less lucrative for the Olgimskys (who don't care as long as they don't suffer any loss) but it would mean that the people who live here would better be able to care for themselves and the land with no need to think of supporting an entire country off the backs of one small community. The occupation of the Steppe, the running of the Bull Project, will not only destroy the Kin and lower classes, but will also eventually kill the town, the higher classes and even the Olgimskys as well. When the water runs out, it will run out for the lower classes first, but it will eventually run out for everyone.

More on Fat Vlad trying to talk about this all as if it were an inescapable, natural reality (and the Bachelor's fighting against this notion) later. Sort of how some people think that the way the world works, capitalism and such, are natural laws instead of constructed ideas (horrible fallacy).

#Pathologic#Pathologic HD Classic#мор утопия#This game is good about addressing a lot of the horrible realities of the town and how it's being run#I just don't see it talked about that often#Post cannon even in a Termite ending a lot of work needs to be done to do right by the Kin and to even make this town survive long term#So many things are killing it and despite what Fat Vlad says#It doesn't have to be this way

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm sorry and I hate to be a downer but I cannot stop thinking about this. Do you see how long it's taken people to wear masks? As recently as this week there are STILL videos going viral of people -- recording their own stupidity and thinking they're justified in it -- going places without a mask on and harassing retail workers and ultimately getting arrested. Two Canadian grocery shoppers and "REI Karen" all in the last week or two, and probably countless more. Corporations and politicians the world over have been pushing since the pandemic began to reopen, to put countless employees at serious risk in order to turn a quick profit, long term be damned. And this tricks people into thinking that things are okay, and that they're justified in returning to the status quo.

But this pandemic is so concrete. The preventative measures are proven, the consequences are blatant. People have died in droves, and more people than my brain is comfortable with admitting into reality have seen loved ones die of covid and shrugged and said "they were old anyway" or "it was probably a pre-existing condition that did it" or "it's just the flu; the flu does that sometimes." Loved ones. Parents, partners, siblings. All the while, corporations and politicians pushing to reopen reinforces the narrative that it can't be that bad, because the people in charge are ready to return to normal, and if stuff is open again, then it's over, right?

And that's a concrete threat.

Climate change will not be so concrete. It is not the difference of one year's death toll to another; it is not the difference between healthy one month and dead the next. Climate change is a difference in decades. In centuries. It is gradual. Some may say exponential. It is only going to get worse. Parts of the world are already becoming uninhabitable. The first waves of climate migration is happening -- right now, it is happening. Some subtly, as Californians filter out as they realize yearly megafires are the norm now. Some blatantly, as Central America is at this moment experiencing record floods that are destroying entire communities. Once-in-a-century weather events became yearly, and now happen half a dozen times per year.

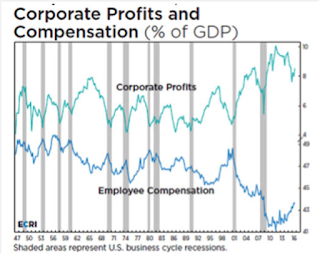

But we're being boiled in the pot, so people can easily say "oh, this one specific element isn't as bad as last year, so it's fine." Capitalism has a vested interest in ignoring the problem. The priority is profits, now, and then more profits tomorrow. Anything beyond that is a problem for the day after.

We will not know the tipping point for our climate when it comes. It is not a concrete thing. There is no wall on the horizon that says "harmful energy emissions must end here." Or, rather, there was a wall that said that, it popped up when science originally proved the existence of climate change, but we already barreled through it. Hell, it was Big Oil who really managed to prove it in the first place, and used it as a weapon in order to melt sea ice in order to operate more profitably, then spent decades and untold amounts of money to downplay and bury their own findings.

This is not a future problem; it is a now problem, and it is being callously ignored at the detriment of every human life. The move toward change, a big, species-wide shift toward environmentalism and zero emissions and so on needed to happen 30 years ago. It needed to happen 20 years ago. It needed to happen 10 years ago. It needs to happen now, and it is not.

Capitalism has actively profited off of a global pandemic, and although we have had the technology and wherewithal to deal with it effectively since the very beginning, capitalists actively fought back at every step of the way, prioritizing profit at the cost of human lives.

This is a microcosm of what's coming. Capitalism actively profits off of the total decline and eventual of Earth's biosphere, and although we have had the technology and wherewithal to stop it -- or at the very least slow it down -- since it was originally identified almost half a century ago, capitalists have been fighting back at every step of the way, prioritizing profit at the cost of the human race.

Insects and marine life are beginning to experience veritable apocalypses. The effects are tangible, but are easy to ignore -- memories of a more stable environment are so far back, they can be safely ignored. And it's only profitable to ignore them.

Remember how many bugs would squish against the windshield of your parents' car, driving down the highway? Remember needing to use wiper fluid to get them off in the middle of a drive? And... when's the last time you saw a bug hit your windshield?

This has been weighing on me so heavily lately. It's making sleep difficult. I can't work up an appetite. I find it so hard to focus. Climate change and capitalism are so intrinsically entwined and we're not going to solve the former without completely dismantling the latter.

Look. All I'm saying is, we'll all be vaccinated this summer. I don't know how to organize anything, but I think it's time for me to do some sort of direct action. And it is long past time for large scale, global climate protests. Something needs to be done. I am so constantly terrified for the future of everything, and I used to be comforted by this sense of... overall cosmic indifference, I guess, that the universe would go on without us. But this fear and this anger that I've had has really begun to shape into something motivating for me. And I really, desperately do not want to just sit back and do nothing anymore. I have too much faith and hope and love inside of me for that.

#at the end of the day. I don't think there's a lot we can do to prevent the worst of it.#but there IS still a lot we can do to... I don't know. shape things to prepare for the fallout#we need a global political system with safety and survival and environmentalism baked in their core#no more of this zero emissions by 2030 shit. zero emissions now. today. complete cold turkey#we need to hope for the best and prepare for the worst and have systems in place so that#when adverse effects arise. they can be dealt with as efficiently as possible#and protect as many people and animals and as much of the environment as we are capable of

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Zombie symbolism in media? Body snatchers? That sounds extremely interesting 👀👀👀

OOOOOOOOOOH ARE YOU READY FOR ME TO RANT? CUZ I’M GONNA RANT BABY. YALL WANNA SEE HOW HARD I CAN HYPERFIXATE???

I’ll leave my ramblings under the cut.

The Bodysnatchers thing is a bit quicker to explain so I’ll start with that. Basically, Invasion of the Body Snatchers was released in 1956, about a small town where the people are slowly but surely replaced and replicated by emotionless hivemind pod aliens. It was a pretty obvious metaphor for the red scare and America’s fear of the ‘growing threat of communism’ invading their society. A communist could look like anyone and be anyone, after all.

Naturally, the bodysnatcher concept got rebooted a few times - Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1978), Body Snatchers (1993), and The Invasion (2007), just off the top of my head. You’re all probably very familiar with the core concept: people are slowly being replaced by foreign duplicates.

But while the monster has remained roughly the same, the theme has not. In earlier renditions, Bodysnatchers symbolized communism. But in later renditions, the narratives shifted to symbolize freedom of expression and individualism - that is, people’s ability to express and think for themselves being taken away. That’s because freedom of thought/individuality is a much more pressing threat on our minds in the current climate. Most people aren’t scared of communists anymore, but we are scared of having our free will taken away from us.

The best indicator of the era in which a story is created is its villain. Stories written circa 9/11 have villains that are foreign, because foreign terrorism was a big fear in the early 2000s. In the past, villains were black people, because white people were racist (and still are, but more blatantly so in the past).

Alright, now for the fun part.

ZOMBIES

Although the concept has existed in Haitian voodooism for ages, the first instance of zombies in western fiction was a book called The Magic Island written by William Seabrook in 1929. Basically ol Seabrook took a trip to Haiti and saw all the slaves acting tired and ‘brutish’ and, having learned about the voodoo ‘zombi’, believed the slaves were zombies, and thus put them in his book.

The first zombie story in film was actually an adaptation of Seabrook’s accounts, called White Zombie (1932). It was about a couple who takes a trip to Haiti, only for the woman to be turned into a zombie and enchanted into being a Haitian’s romantic slave. SUPER racist, if you couldn’t tell, but not only does it reflect the state of entertainment of the era - Dracula and Frankenstein had both been released around the same time - but it also reflects American cultural fears. That is, the fear of white people losing their authoritative control over the world. White fright.

Naturally, the box office success of White Zombie inspired a whole bunch of other remakes and spinoffs in the newly minted zombie genre, most of them taking a similar Haitian voodoo approach. Within a decade, zombies had grown from an obscure bit of Haitian lore to a fully integrated part of American pop culture. Movies, songs, books, cocktails, etc.

But this was also a time for WWII to roll around and, much like the Bodysnatchers, zombie symbolism evolved to fit the times. Now zombies experienced a shift from white fright and ethnic spirituality to something a bit more secular. Now they were a product of foreign science created to perpetuate warmongering schemes. In King of Zombies (1941), a spy uses zombies to try and force a US Admiral to share his secrets. And Steve Sekely’s Revenge of the Zombies (1943) became the first instance of Nazi zombies.

Then came the atom bomb, and once more zombie symbolism shifted to fears of radiation and communism. The most on-the-nose example of this is Creature With the Atom Brain (1955).

Then came the Vietnam War, and people started fearing an uncontrollable, unconscionable military. In Night of the Living Dead (1968), zombies were caused by radiation from a space probe, combining both nuclear and space-race motifs, as well as a harsh government that would cause you just as much problems as the zombies. One could argue that the zombies in the Living Dead series represent military soldiers, or more likely the military-industrial complex as a whole, which is presented as mindless in its pursuit of violence.

The Living Dead series also introduced a new mainstay to the genre: guns. Military stuff. Fighting. Battle. And that became a major milestone in the evolution of zombie representation in media. This was only exacerbated by the political climate of the time. In the latter half of the 20th century, there were a lot of wars. Vietnam, Korea, Arab Spring, Bay of Pigs, America’s various invasions and attacks on Middle Eastern nations, etc. Naturally the public were concerned by all this fighting, and the nature of zombie fiction very much evolved to match this.

But the late 1900s weren’t just a place of war. They were also a place of increasing economic disparity and inequal wealth distribution. In the 70s and 80s, the wage gap widened astronomically, while consumerism remained steadily on the rise. And so, zombies symbolized something else: late-stage capitalism. Specifically, capitalist consumption - mindless consumption. For example, in Dawn of the Dead (1978), zombies attack a mall, and with it the hedonistic lifestyles of the people taking refuge there. This iteration props up zombies as the consumers, and it is their mindless consumption that causes the fall of the very system they were overindulging in.

Then there was the AIDS scare, and the zombie threat evolved to match something that we can all vibe with here in the time of COVID: contagion. Now the zombie condition was something you could get infected with and turn into. In a video game called Resident Evil (1996), the main antagonist was a pharmaceutical company called the Umbrella Corporation that’s been experimenting with viruses and bio-warfare. In 28 Days Later (2002), viral apes escape a research lab and infect an unsuspecting public.

Nowadays, zombies are a means of expressing our contemporary fears of apocalypse. It’s no secret that the world has been on the brink for a while now, and everyone is waiting with bated breath for the other shoe to drop. Post-apocalypse zombie movies act as simultaneous male power fantasy, expression of contemporary cynicism, an expression of war sentiments, and a product of the zombie’s storied symbolic history. People are no longer able to trust the government, and in many ways people have a hard time trusting each other, and this manifests as an every-man-for-himself survivalist narrative.

So why have zombies endured for so long, despite changing so much? Why are we so fascinated by them? Well, many say that it’s because zombies are a way for us to express our fears of apocalypse. Communism, radiation, contagion - these are all threats to the country’s wellbeing. Some might even say that zombies represent a threat to conversative America/white nationalism, what with the inclusion of voodooism, foreign entities, and late-stage capitalism being viewed as enemies.

Personally, I might partly agree with the conservative America thing, but I don’t think zombies exist to project our fears onto. That’s just how villains and monsters work in general. In fiction, the conflict’s stakes don’t hit home unless the villain is intimidating. The hero has to fight something scary for us to be invested in their struggles. But the definition of what makes something scary is different for every different generation and social group. Maybe that scary thing is foreign invaders, or illness, or losing a loved one, or a government takeover. As such, the stories of that era mold to fit the fears of that era. It’s why we see so many government conspiracy thrillers right now; it’s because we’re all afraid of the government and what it can do to us.

So if projecting societal fears onto the story’s villain is a commonplace practice, then what makes zombies so special? Why have they lasted so long and so prevalently? I would argue it’s because the concept of a zombie, at its core, plays at a long-standing American ideal: freedom.

Why did people migrate to the New World? Religious freedom. Why did we start the Revolutionary War and become our own country? Freedom from England’s authority. Why was the Civil War a thing? The south wanted freedom from the north - and in a remarkable display of irony, they wanted to use that freedom to oppress black people. Why are we so obsessed with capitalism? Economic freedom.

Look back at each symbolic iteration of the zombie. What’s the common thread? In the 20s/30s, it was about white fright. The fear that black people could rise up against them and take away their perceived ‘freedom’ (which was really just tyrannical authority, but whatever). During WWII, it was about foreign threats coming in and taking over our country. During Vietnam, it became about our military spinning out of control and hecking things up for the rest of us. In the 80s/90s, it was about capitalism turning us into mindless consumers. Then it was about plagues and hiveminds and the collapse of society as a whole, destroying everything we thought we knew and throwing our whole lives into disarray. In just about every symbolic iteration, freedom and power have been major elements under threat.

And even deeper than that, what is a zombie? It’s someone who, for whatever reason, is a mindlessly violent creature that cannot think beyond base animal impulses and a desire to consume flesh. You can no longer think for yourself. Everything that made you who you are is gone.

Becoming a zombie is the ultimate violation of someone’s personal freedom. And that terrifies Americans.

Although an interesting - and concerning - phenomenon is this new wave of wish fulfillment zombie-ism. You know, the gun-toting action movie hero who has the personality of soggy toast and a jaw so chiseled it could decapitate the undead. That violent survivalist notion of living off the grid and being a total badass all the while. It speaks to men who, for whatever reason, feel their masculinity and dominance is under threat. So they project their desires to compensate for their lack of masculine control onto zombie fiction, granting them personal freedom from obligations and expectations (and feminism) to live out their solo macho fantasies by engaging in low- to no-consequence combat. And in doing so, completely disregarding the fact that those same zombies were once people who cruelly had their freedom of self ripped away from them. Gaining their own freedom through the persecution of others (zombies). And if that doesn’t sum up the white conservative experience, I don’t know what does.

So yeah. That’s zombies, y’all.

Thanks for the ask!

#dude#film stuff is one of my main hyperfixations#but to be fair i have a lot of hyperfixations#why do you think this blog exists#ask#fish post

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Executive Action Assessment of Climate Science and Climate Change 🌎

Visit the White House website to answer the following questions; choose the Issues tab from the upper-left menu and select the category which represents your civic action issue. Website: https://www.whitehouse.gov/issues/

Briefly summarize (four-to-five sentences) President Trump’s stance on your issue.

Trump in office has repealed or announced the intention to repeal over 50 act the related environmental regulations saying “We are going to get rid of the regulations that are just destroying us. You can’t breathe—you cannot breathe.” He has called for increased drilling on national parklands. It appears that trump views the environment and climate as an infinite resource and therefore has his policy match that belief because they don't seem to match even the most conservative estimates of projected climate change.

Do you agree or disagree with his position? Explain.

In theory, I agree to an extent with his position but after reading some of his remarks it's difficult to substantiate what he says with his actions. His appointed head of the EPA is a former coal lobbyist. He even tweeted in January saying “What the hell is going on with Global Warming? Please come back fast, we need you!” when talking about the midwest’s cold front that researched record-breaking low temperatures. These temperatures were actually the result of global warming and climate change if trump believed science was real at all.

Next, go to https://www.usa.gov/branches-of-government#item-214500 Please visit the Cabinet website which manages your issue to answer the following questions.

Which Executive Cabinet manages your issue?

The Department of the Interior

What is the Cabinet’s mission statement (usually on the homepage)? Explain if it relates to your issue.

“The Department of the Interior (DOI) conserves and manages the Nation’s natural resources and cultural heritage for the benefit and enjoyment of the American people, provides scientific and other information about natural resources and natural hazards to address societal challenges and create opportunities for the American people, and honors the Nation’s trust responsibilities or special commitments to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and affiliated island communities to help them prosper.”

The Department of the interior relates to my topic because it is the only executive department that on any level related to the environment and climate change. It deals with natural resources and hazards that can affect the future climate.

Who is the secretary of the department (usually under the about tab) What is their background? Are they professionally qualified to lead this department or are they merely a political appointment? Explain how this impacts the department and your issue.

David L. Bernhard is the secretary of the Department of the Interior. He is an avid hunter and had been on the Game and Inland Fisheries for the Commonwealth of Virginia and an oil lobbyist. He does have some background with the department and with politics because he was a lobbyist. This could leader of the department’s mission statement it be compromised.

Explore the Cabinet’s Programs and Services. Which would be suitable for responding to your issue? Briefly identify and explain them.

The Department of the Interior has a bureau called the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement. It deals with the environment and protecting and coming up with solutions after environmental disasters like oil spills. Protecting the environment is an important step in preventing climate change because our nation's natural lands and forests serve as carbon capture sites and are vital to the health of our planet.

Based on your review of the President’s website and Cabinet programs, assess the executive action taken on your issue. Explain your level of satisfaction and provide examples. Is this department one which President Trump wants to cut funding? If so, do agree that this is a viable approach to resolving your issue? How would decrease funding to this department affect your civic action issue?

I am extremely dissatisfied with the current actions being taken in regards to my issue of climate change and climate science. It is evident that President Trump is blatantly ignoring science in favor of his own delusions. He took the United States out of The Paris Climate Accord and has also repealed or expressed the desire to repeal laws that are helping to protect our environment not and in turn the overall health of our planet's climate. Trump is definitely cutting funding to environmental initiatives and ignoring the broad range of impacts climate change will have on the country and the world, to both the people and coastal cities, agriculture, extreme weather events and his favorite the economy. Decreased funding would suspend/prevent actions by the federal government that would affect the whole country instead of each individual state. It means we will continue to poison the earth with nothing in our way until it's too late and Trump is dead.

SACAPS—https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/11/climate/epa-science-trump.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

what is the subject of the article?

The Trump administration wants to limit the scientific and medical research that the government can use when determining public health regulations.

Who is the author?

The author Lisa Friedman is reported on the climate desk and she focuses on climate and environmental policy in our nation’s capital.

What is the context?

The article was written in lieu of A new draft of the Environmental Protection Agency proposal that makes it more difficult to use scientific facts and a scientific basis for laws involving the environment.

Who is the intended audience?

The intended audience is everyone, the New York Time is A little left-leaning but the article isn't an opinion piece and states facts,

What is the bias and perspective of the author?

The author is evidently pro-environmental protection and climate change prevention.

What is the significance of the article?

This article demonstrates the Trump administration's policy towards the climate. Repeal, repeal, repeal. He has done much to reverse environmental protection laws since entering the office in 2017.

Do you agree with it? Why or why not?

I agree with it as much as you can agree with a pretty much-unbiased article. Based on science I understand the severe consequences this kind of action by our Commander and Chief can have on the lives of the citizens he serves. Ignoring qualified professional's advice is dumb and is a disservice to the people he serves, to all of us.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Heya hope you’re doing well! For the end of year asks, 1 and 24?

I’m doing OK! I keep forgetting to post this, or adding onto it. But I don’t want it to be lost whenever my browser next crashes. So, let’s post this!@meanwhileonwednesday also asked me to answer them all, so I’m gonna combine both.

1) what did you learn about yourself this year?

I learned a lot about myself. I underwent some careers counselling, which has been an itneresting ride, and given me lots of tools to reflect on what I want out of work. It’s hard, because I realised that I (and probably all of us) tolerate so many working conditions that I don’t inherently like or flourish under. I like to take my time on one problem at a time; in medicine you’re being constantly interrupted by like 10 different people who then remind you multiple times about the thing you were doing til someone else interrupted you, and constantly re-jigging your to-do list to accommodate changes in urgency. I realised I like to make people feel better even more than I like to ‘fix’ things. I realised that the reality of what work in a busy hospital is like completely colours my perception of specialties; I can’t unsee the kinds of shifts I’ve had to work. It gave me a lot of food for thought, and I hope it helps me pick something I’m happy with. And having started dating again towards the end of the year, I’ve had to think a lot about who I really am, and what I really want or need. It’s not easy shining an honest light on yourself; what you realise isn’t always flattering (I don’t often spend enough time doing non-work related things, and I’m too much of an introvert for most people, probably). But this allows you to be honest about what would make you happy; for example, I’d hever chase some guy who loves to go clubbing on a regular basis, because we’d be spending every evening apart.

2) best moment of the year?

I don’t know. There were lots of litle modest ‘best moments’, but I’m not sure I can thing of any one big thing.

3) worst moment of the year?

Burnout Time wasn’t a moment, but it wasn’t a good time in general. I’m going to vote it number 1. Though it has some stiff competition. I’ll stick to just one, because nobody wants to read a long list of sad things.

4) what was the biggest change you experienced this year?

I realised that I wouldn’t let training and medicine destroy me. Not that I planned to before, but there’s a lot of fear and anxiety at every stage of the game in medicine. You spend med school anxious in case they kick you out. You spend foundation training anxious in case you kill someone or they kick you out. Then you finish that part of your training, and start the next and its... more of the same? And when you struggle and feel bad, so often your first thought isn’t “I feel horrible, this is bad for me and I need help” but “as long as I am functional at work, then it’s OK as long as they don’t kick me out”. But that doesn’t help you get better, it only piles more pressure on you when you need help. It turns out that I discovered they don’t kick you out of training as easily as my darkest thoughts imagined. But it made me realise I could never let this job destroy me; there is so much to live for and enjoy outside of medicine. There are so many other ways to be happy.

5) best song of the year?

Aah I’ve listened to so many songs over the course of a year, how could you pick one. I’d blatantly favour the ones I obsessed over most recently. Hmm. I listened to Vitali’s Chaconne on a loop when revising, so let’s go with that.

6) best album of the year?

I rarely listen to entire albums, because I tend to discover songs randomly and individually. But I loved that my friend and I discovered we both loved Indila’s music really randomly.

7) what’s one thing that happened this year that you want to change?

Towards the end of the year, I had to take a break from making and posting comics. Between burnout and work things, I just didn’t have the time, energy or inspiration to give it what it needed. I hope to get back into it this year; I really miss making my comic.

8) best book/book series of the year?

I’m gonna vote Good Omens. I know people joke about something curing their depression. But yeah, it sort of did with me. It made me see the light at a difficult time, and despite all the stress and sadness and numbness I was going through, it made me laugh and feel joy and appreciate what words could do again. It rekindled a light that had burned very low, and I’m forever grateful for that; it holds a special place in my heart now.

9) best television series?

Hard for me to pick one. I’m watching The Dragon Prince right now, and it’s great! Reminds me of ATLA in the best ways. Honourable mention to Cells at Work for combining three of my interests (medicine, anime and cute things) into one.

10) how was your love life this year?

I actually bothered to try to have one! Only toward the end of the year, though, so we’re on baby steps right now. I’ve talked to and met a few interesting people, even ones that I couldn’t pursue anything further with. I’ve also read like a million really bad profiles, had way too many half-assed messages and conversations.

I hate the initial bit, where you should try to be yourself and need to be open and vulnerable to really getting to know people, but equally people can just drop out of talking with you or dating you just like that. It’s something much easier to do when you meet online and don’t know each other than when you meet at uni, and I certainly seem to see it a lot more now in online dating than meeting people IRL. Where you get dumped or dump someone but you at least have s a sense of completion. I don’t like how easily the mind wanders over to ‘damn it, he’s ghosted me’ If someone doesn’t reply for a few days, but then again, the fact that lots of people do just ghost doesn’t help that.Still, I remind myself that there’s no use worrying about it; if someone will dump you or isn’t right for you, then there’s nothing you can do to change it.

There are some nice people out there, and I’m interested to see where it goes. Hopefully without too much anxiety, preoccupation or heartbreak on the way; that was one part of dating that I absolutely did not miss in my single carefree years.

11) what made you cry the most this year?

I find it hard to quantify what made me cry the most; I had a lot of tough times.

Actually, no, on second thought, I think I know what made me cry the most; PMS. Hands-down the winner. What a menace; it’s a real pain. Would not recommend PMS as an experience to those of you unfamiliar with it.

12) biggest regret of the year?

I try not to look back and regret things. I don’t want to say I regret burning out, because frankly that isn’t a choice I made, so I don’t feel bad about it. It’s unfortunate that it’s made my life a bit more complicated, but it’s manageable. So I try not to dwell on that or regret it.

I feel sad that I put my comic on hiatus, because I managed to balance it through so many tough times, so pausing kind of felt like admitting defeat, or losing a part of myself. But it needed to be done.

13) best movie of the year?

It’s late and I actually can’t even remember which movies I saw this year. I think I saw Mary and the Witch’s Flower in this past year, so I’m going to go with that. Because I’m really excited to see where Studio Ponoc takes things, and if they will carry on a Ghibli-ish legacy or do something new.

14) favourite place you travelled this year?

I went to Poland, twice. It was great! I’m slowly trying to get around all the European capitals, and it’s really nice to learn more about the places you go. I never feel like I’ve seen everything there is to see, which I guess is motivation to come back another time...

15) did you make any new friends?

Always. Yep, the benefit of moving to new jobs on a regular basis means that you get to meet new people, a lot. I’ve seen one of my FY1s develop into a great SHO and become a good friend. I’m so proud of them.

And hey, always making new friends here! I love our community, and whilst I can’t remember exactly when I befriended most of you (or got befriended), I am truly glad that I have.

16) did you learn anything about your sexuality this year?

Yep, I don’t think you ever stop learning. I’m looking forward to always finding out more. I don’t feel the need to share it, though :P Some things are better left private.

17) what are some hobbies that you developed?

Most of my hobbies are the same as they always were. However, I feel that I have played a lot of new board games, I continued to D&D without being an utter disaster, and now feel uh, sort of actually competent at this sort of thing. And I have collected some awesome dice.

18)what surprised you the most this year?

We’re still doing this Brexit thing. I don’t know; I’m not sure politics can surprise me much anymore. It’s still free to disappoint, though. Actually, a few patients survived who I didn’t expect. And some people died suddenly that we didn’t expect to pass at that point. So medicine is always surprising.

19) do you look different from the beginning of the year?

I have more grey hair. Like a LOT. My hair evidently plans to go silver way before I would have expected to. At this rate, I won’t make it to 40 with any brown hair left! My hair is almost waist length so it hasn’t changed all that much apart from the fact that it really wants me to cosplay white haired anime characters.

20) how did this year treat you in general?

People died. People got sick. People in my personal life, not patients, that is. It’s harder to deal with it when it’s not at work; when it’s people you know and care about. My parents had multiple procedures or surgeries. I sort of burned out at one point and vaguely considered if the path I am on is for me. I did a bit of soul-searching to try to work out what I really want, and what I really need. I’m still not sure I understand, but I’m getting closer.

21) what message would you give yourself at the beginning of the year?

You’ll live. It’s OK, it’ll work out, and you’ll get through it, like you always do.

22) has your fashion style changed this year?

Not really. I have too many clothes (mostly for work, if I’m honest) so I didn’t buy many this year. I definitely need to sell or give away some of the ones that just aren’t ‘me’ any more, though. I sometimes hold on to clothes for a long time, but in the end when it doesn’t feel right dressing like I did say, 10 years ago, then I feel the need to revamp my wardrobe.

23) one of the best meals you��ve had this year?

My mum randomly started making my favourite food more often, and I’m really happy! I keep asking her if there’s some kind of ulterior motive XD

24) who has made the biggest impact in your life this year?

Hmmm it’s really tough to think of any one particular person. Some of the stronger experiences with people were negative, but I refuse to dwell on them or name them; to single them out gives them a power and importance they don’t deserve. So instead I’d just have to say my network of friends and family, for keeping me going’ they have done a lot for me this year. Lots of little and big things that make me feel so loved and cared for.

25) what’s one thing that you hope will continue next year?

I will keep trying to do my best, and keep trying to look at the bigger picture. I’ll keep working on not letting medicine take over my life. I’ll keep trying to be a better doctor. I’ll keep making time for friends and family. I’ll keep trying my best to meet new people, and not let the times it didn’t work out get me down.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I fell in love with Lotor and then realized he's a fucking idiot

AKA: a (bad) dissertation on Lotor's potential as a character and how his motivations basically undermined all of it.

Spoilers through the end of season 6; written pre-season 7.

Let's just get my credentials out of the way first: I recently watched Seasons 1-6 of Voltron in the span of about 2 months. I am vaguely aware of some fandom discourse. I know very little about the original Voltron show or its plot except what I've gathered from a single day browsing the wiki. And finally, I love manipulative trash cans. Doesn't matter if they've got gray morality, complete amorality, or if they're just plain evil: I unironically enjoy their existence (the only exception is Ni Jianyi who terrifies me, but, well, I attribute that to good writing).

So imagine my delight when in his very first episode, Lotor demonstrated that he'd been very competently keeping tabs on the political status of the central Galran Command even while exiled by: rooting out his main opponents, publically humiliating them, and positioning his Generals strategically in the audience to ensure that the crowd's response was positive and enthusiastic, all within probably a quintant or two of getting back. ....And then he blatantly admitted to manipulating public opinion not five minutes later. ....While looking unfairly gorgeous.

As character introductions go, it set a really fucking high bar, and I think a lot of people were immediately invested in learning what his endgame was. Regardless of whether his ultimate goals were ‘good’ or ‘evil’, people expected them to be competent and..... worthy. Worthy of all the time and effort that was put into this character, and the show in general. And then S6 happened. So buckle up friends because we’re gonna take an in-depth look at his journey from potential political mastermind to... merely obsessed, like his father.

Immediately after being appointed Emperor Pro Tem, Lotor goes out and retakes a recently liberated planet to bait out Voltron. Which is.... something that we never actually saw his father do. Ever. Zarkon seemed content to let rebel planets stay lost, which is really silly and not at all a sustainable method of ruling an empire (suggesting that Zarkon probably would have lost control of a large portion of the Empire sooner or later anyway even if Voltron hadn't managed to destroy him in Blackout). Anyway, it showed that Lotor is a competent tactician, since he gets exactly the information he needs and does way more damage to Voltron than he probably expected to. He even follows up properly by calling in reinforcements to save his ass fortify the newly retaken planet, which may have given him a nice boost in popularity back home.

(It also set up a number of obvious parallels between Lotor’s Generals and the Paladins of Voltron. Excellent teamwork and loyalty? Check. Cheerful personality? Check. Big strong type? Check. Brooding, dark-haired second in command? Check. ...Wait, that makes Narti Pidge’s parallel. Or maybe Shiro’s, since she’s sometimes mind controlled....? ANYWAY. )

We start to see a couple cracks in episodes 4 and 6, because it becomes clear that Lotor is actually not spending that much time managing the Empire. He's way more interested in getting the materials to build the Sincline ships. At this point in the series he's still doing a great job of evading detection and throwing misdirection everywhere to keep Haggar from guessing what he's up to, so it starts to look like he's trying to undermine the Empire from within. I mean, think about it: he set himself up publically as a celebrity to strengthen the Empire, and then he disappeared and did none of that. He even exiled Throk, one of his biggest political enemies to Buttfuck, Space - Population: Ice Worms after his public humiliation. Which is a really bad idea if you want to keep a guy out of trouble, but a really good idea if you want to give a guy the time and space he needs to get angry, start another rebellion, and further destabilize the Empire.

Lotor has lived in exile for years; he himself is the perfect example for how people rebel when sent to some corner of the universe with minimal supervision. He should know better than anyone that exile is a bad way to actually get rid of someone, yet he does it anyway.

Season 4 pretty much cements the idea that Lotor never actually wanted to rule the current Galra Empire, and was only using its resources for his own gain. He's removed from the position of Emperor Pro Tem with minimal fuss, and probably would have been quite happy to lay low for a while afterwards.... except that his dad then tries to kill him and he does the really dumb thing. I think almost everyone agrees that killing Narti was one of the dumbest things Lotor could have done. He could knock her out? Kill the cat?? Anything other than ruin his own party???

But nah. He stabs Narti and immediately the parallels between his group of Generals and Voltron shatter, because they betray him and try to turn him in to Haggar. Or, rather, he betrayed them.... .....actually maybe the parallels still apply, because I'm pretty sure that if Kuron had actually stabbed any of the Paladins at any point, the rest would have flipped out as well, so really the entire arc may be more of a statement on Galra culture as a whole.....

ANYWAY, the whole Narti thing might look like the place where everything starts to go south, but it actually doesn't ruin any of Lotor's potential. Killing Narti could either be the callous act of someone who's bad at communication and doesn't actually care about his team (which is his team's interpretation, and a fair one), or it could be taken as a really stupid moment of panic, which I’d argue is a little more interesting, since Lotor never panics. But either way, the outcome was the same: as soon as he had control taken away from him, he turned desperate and all his flaws started to come out. Narti's death was one of the dumbest things Lotor ever did, but I also want to argue that it's the one act that opened up his narrative potential the most, because it could have sparked some interesting discussion about whether all of his actions are due to being arrogant, maladjusted, and self-absorbed... or if any can be attributed to fear.

Unfortunately, while fanfiction capitalized on that potential immediately, the show never really did. I was hoping for a season of self-reflection as Lotor used his intelligence and manipulative skills to sway Voltron to his side and overthrow Zarkon and Haggar in retaliation for his one miscalculation of the series. I wouldn't even have been mad if he had betrayed Voltron again at the end, because it would have been in keeping with his suggested characterization so far, and I like competent opponents with actual realistic goals.

Season 5 looked like it was on track! Lotor was clearly still doing his best to manipulate Voltron as much as he could from a prison cell, furthering his goals despite his enormous setback. It's not really clear how many of his accomplishments during this season are due to careful planning and how many are due to luck; did he know Zarkon would offer the prisoner exchange? Did he know Sendak was going to be at the Kral Zera? Did he know Shiro was Kuron and would secretly hand over the Black Bayard so he actually had a fighting chance against Zarkon? ....Probably no to the last one, since it hinged on Honerva remembering her son, but who knows.

Regardless, Lotor takes a lot of risks and makes a lot of progress. He actually becomes Emperor. Dude, holy shit, congrats. Take a breather and regroup!! That big of an milestone should have been enough for anyone, but instead he pushed his luck searching for Oriande, becoming completely dependent on Allura for her guidance and her protection, and then he failed the White Lion's trial. Like, completely whiffed it. Do not pass Go, do not collect $200. The S6 finale makes it clear that Lotor's morals and goals are almost completely opposite Allura's, and that should have been the perfect place to start developing him further as.... you know, an actual emperor and moral counterpoint?

Instead, we got Season 6, where Lotor turned his fakeness meter up to 11 to seduce Allura. ...Badly. Like... really badly. ... Okay, listen the nanny thing was weird, there’s no denying that. She showed up for one episode out of completely nowhere and was never mentioned again. But Lotor felt more natural during that first episode of S6 than he did the entire rest of the season while romancing Allura, and I think that was probably on purpose. His voice and his face and his smile when he spoke with Allura were all the same ones he used during his first scene in the gladiator ring, when manipulating public opinion. I don’t think we were ever really meant to believe in Lotor’s feelings for Allura when his very character was introduced with the same sort of deception.

And all of that would still have been fine if he hadn’t had such a stupid final motivation. I suppose Season 6 makes sense when you consider that his ultimate goals actually had nothing to do with the Galra Empire, but it doesn’t feel like a good culmination of his character arc. So, knowing that his ultimate goal was the creation of a new Altean Empire, Let’s briefly review:

- Lotor spent three seasons manipulating the public to gather support and popularity. The conclusion of this was Kral Zera, where he actually became Emperor. But none of this matters. “Emperor of the Galra” is actually unrelated to “Emperor of the New Alteans”, or whatever. Unless his plan was to marry Allura and spend the next 10,000 years carefully integrating his Alteans into the Galran Empire while giving them every advantage possible, becoming the Galran Emperor didn’t actually have much to do with his Altean goals. His Alteans aren’t Galra citizens. So why spend that much time making himself popular with a race he hated? Narcissism???

- Lotor may have also spent three seasons subtly supporting rebellion across the Galran Empire, because he made a couple conspicuously bad decisions when it came to handling his political opponents/rebellion planets. Conspicuously bad enough to be deliberate, given what we know of him as a competent tactician. But supporting rebellion would only have helped him if he had planned to use rebellion to take over, and we just established that being the Galra Emperor doesn’t actually help his main goals. So does that make all the seasons of subtle rebel support.... a side-effect? Carelessness? Supporting the Voltron Coalition didn’t really matter if he intended to replace Voltron with his own shiny robot.

- Lotor’s generals are all half-galra. Originally, it seemed like he had chosen to align himself with societal outcasts because he could inspire loyalty and comraderie in them, and because after a lifetime of discrimination at the hands of Central Command, they’d probably be willing to support his rebellion. That’s, like, a huge fanfic canon. But instead, his final, power-driven speech suggests that he chose half-galra Generals simply because he couldn’t stand to work with full-blooded Galra. Which makes his close-knit team and all their beautiful parallels with Voltron... accidental??

- Lotor spent let’s say... a season and a half? trying to seduce Allura. This makes the most sense out of all of his goals, because marrying into the last remaining full-blooded Altean royalty totally fits with the New Altean Empire. What’s stupid here is how he handled it. Instead of coming clean about his Altean colony and, I don’t know, properly hiding his tracks as soon as he realized he could marry royalty?? He left the quintessence farm up and running. We know Lotor can get into and out of the rift way faster than Keith and Krolia, so there was really nothing stopping him from going to hide a couple skeletons in his closet sooner than never. He could probably have won Allura’s loyalty forever if he had presented her with an Altean colony and pretended to need her help restoring Altean culture; instead, he did dumb.

I’m just... I’m sad, okay? I’m not sad because he was evil; I’m sad because he didn’t want to be his father, and he absolutely turned into his father, and there were almost no signs of that until the very end. He could have been evil and still competent! While there are parts of Lotor that are really well written, it seems like they were all pushed to the side to make way for his obsession - an obsession he wasn’t even that obsessed about previously!!! - in the final couple episodes of Season 6, and he just... does so many stupid things.

So really, in conclusion, either Lotor got quintessence sickness, Haggar made a Lotor clone while he was visiting her that one time, or we should all be more sympathetic of Zarkon's stupidity in Seasons 1 and 2 because clearly Galra politics are infuriating enough that being Emperor for a couple pheobs was enough to make Lotor lose his McFreaking Mind. Zarkon had been Emperor for 10,000 years; it's understandable that he was a little quirky.

Also, I saw a post a few weeks ago that basically said “the worst thing that can happen to Lotor is that he comes back from the void and gets obsessed with Allura like in the original show”, and I wish I could find it again, so if you know that post, pls link me. And I agree, that would really really suck, I don’t want that. But I’m hopeful that the writers just decided to adapt his character a little, so that instead of being obsessed with the Altean Princess, he was instead obsessed with Altea, and therefore that arc is already over. But I guess we’ll find out soon! Fingers crossed.

Feel free to comment with alternate interpretations of everything here!

#voltron#voltron the legendary defender#lotor#vld lotor#long post#this is a very bad dissertation#the final message is I'm sad#that's it that's the point of this post#not lotor hate though#more like#I wish you were better#this is my first post in the voltron fandom#and possibly the last#I just#lotor y#six more days my dudes#six more days

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Academic freedom is under attack in Modi’s India | Human Rights News

Last year I had the opportunity to listen to the prominent Indian intellectual and author, Anand Teltumbde, speak at an academic conference in Delhi. At one point in his speech, he got teary-eyed and told the audience that he has lost all hope because India’s transformation into a “Hindu nation” under Prime Minister Narendra Modi appears complete. Having followed his profound anti-caste scholarship and civil rights activism closely over the years, I was heartbroken to witness his despair. I wanted to walk up to him and tell him that things will eventually get better. But since I did not know him personally, I chose not to.

I thought of him and his sorrow about the state of India often in the following months. I was miles away in the United States studying towards a PhD, but I was aware of the increasing repression of dissident academics and student activists in my home country. So when I read about Professor Teltumbde’s arrest in April this year, it felt personal. He was accused of having links with Maoist rebels and conspiring against the government, including “plotting the assassination” of Modi. Countless legal experts agree that the charges are fabricated and politically motivated, but he remains behind bars to this day.

Sadly, Teltumbde is not the only scholar to have fallen victim to the ongoing witch hunt against government critics in Indian academia – many public intellectuals have been accused of endangering “national security” and imprisoned for challenging Modi’s authoritarianism in recent years.

Just last month, a report published by the international NGO Scholars at Risk exposed the steady curtailment of academic freedoms in India under the Modi government. While the findings of the report were undoubtedly disturbing, they did not come as a surprise to anyone who has been following the news from India closely.

Since assuming power in 2014, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been systematically destroying the secular, democratic foundations of India and transforming the country into a strictly Hindu nation. BJP’s Hindu supremacist ideology portrays Muslims as the nefarious “other”. Moreover, Hindu supremacy is about the hegemony of upper-caste Hindus. Lower castes, which constitute the majority of the Indian population, are on one hand told to be proud Hindus, and on the other hand, oppressed violently because the caste system deems them inferior. It is in this context that anti-caste, Dalit (formerly “untouchable”) scholars such as Teltumbde, as well as Muslim and other dissident academics, are accused of being “anti-national” and prosecuted with fabricated charges.

Last August, India revoked the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, a Muslim-majority region over which both India and Pakistan claim jurisdiction. Following this move, the world’s so-called “largest democracy” imposed a communication lockdown in the region, closed all educational institutions and erected police barracks in university campuses.

Without access to the internet and university campuses, scholars and students from the region were left struggling to study, teach and communicate with each other and the outside world. To make matters worse, Hindu nationalist groups supporting the government started attacking Kashmiri students in other parts of India for merely “looking Kashmiri”. Scholars working on subjects related to Kashmir, meanwhile, have been summoned by state authorities to explain why they are doing “anti-national” research. Attempts by the Indian government and its supporters to silence dissenting voices in academia have not been contained within the country’s borders, either. Letters accusing Kashmiri scholars based in the US of “supporting terrorism” have been sent to the universities they are associated with, and events they participate in have been disturbed by Modi’s supporters.

Just a few months after the revocation of Kashmir’s special status, Modi’s BJP rammed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which offers an accelerated path to citizenship to migrants who are not Muslim, through India’s parliament.

On university campuses across India, students held unprecedented, peaceful protests against this blatantly discriminatory law. These protests were met with brutal state repression. Police and paramilitary forces entered university campuses and fired tear gas and rubber bullets and beat up students. In some cases, officers stood by and watched as Hindu nationalist groups stormed the same campuses, vandalised property and attacked anti-CAA student protesters.

Indian scholars and students studying abroad, such as myself, watched these events in horror. Many of us published open letters against the CAA and in support of the protesters. Despite a large number of signatories including many prominent scholars, these letters made little difference to the Modi government – it continued its repression of peaceful protesters, which eventually resulted in an anti-Muslim pogrom in Delhi that claimed 53 lives.

This year, the COVID-19 pandemic provided another opportunity for the government to clamp down on any criticism of its policies and actions. As protests became difficult and at times “unlawful gatherings” amid the pandemic restrictions, the Modi government decided to utilise its powers to further silence dissenting voices. It started wielding the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act – which gives the state the power to designate an individual as a terrorist before being proven guilty by trial – against dissident scholars and students participating in anti-CAA protests and anti-caste activism.

In July, at the height of the coronavirus crisis, the BJP government also approved the National Education Policy 2020 (NEP) outlining its vision for India’s education system. Not only does NEP pave the way for further privatisation of education and the erosion of the federal character of the educational structure, BJP’s rhetoric around NEP reveals how Hindu supremacy is shaping education in India.

BJP officials’ discussion of NEP has been replete with proclamations that education needs to be grounded in “culture” and “traditions” and that India was a “knowledge superpower” in the ancient past, before Muslim invasions and British colonialism.

According to Education Minister Ramesh Pokhriyal, the NEP is based on the dictum that “nation must”. Under this ideological design, questioning caste oppression, Islamophobia, patriarchy and crony capitalism is “anti-national” and scholars who dare to do so lack “character”.

The NEP prioritises the development of “practical skills” over critical thinking abilities. I, myself, have seen what this means during my undergraduate studies in one of the country’s premier engineering and science institutes, the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT). It means keeping the curriculum and the university atmosphere strictly apolitical, which ensures graduates obtain remarkable technical skills but remain unable to think critically and question oppressive structures.

With Indian engineers and technical professionals working across the world, this issue has global ramifications. After watching my college peers bash affirmative action for Dalit students for years, I was not surprised to find that there is rampant caste discrimination among Indian-origin engineers in Silicon Valley. Having experienced the meritocratic, technocratic environment of the IIT, I was not surprised that Google CEO Sundar Pichai, who is an IIT alumnus, chose to work with the Chinese government to create a censored, trackable search engine rather than question how doing so will endanger human rights in China.

The ongoing unlawful imprisonment of Professor Teltumbde and numerous other scholars is a clear reflection of the bleak state of academic freedom in India. It will take years, if not decades, to undo the damage that Modi and his Hindu nationalist supporters have inflicted on Indian education. It will require university leaders, lawmakers, civil society, and crucially, the international community, urging the state to end repression of ideas and safeguard academic freedoms.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

#humanrights Read full article: https://expatimes.com/?p=15809&feed_id=24012 #asia #humanrights #india #opinions

0 notes

Note

Hello! How are you? I was just wondering if you have an book recs? I want to try read more next year :)

YES. YES I DO FRIEND. I HAVE MANY BOOK RECS THANK YOU FOR ASKING.

I was literally just talking to someone the other day about how much I love giving book recommendations because I just love the idea of getting to show people the books that I have enjoyed.

Now, you didn’t specify, and I could ask, or just take a guess at what genre you’re thinking about, but WHERE WOULD THE FUCKING FUN BE IN THAT.

For the Fiction genre:

Maria Lu’s Legend series is really enjoyable. It’s about a sort of pseudo-fantasy Roman society with magic and intrigue and spies and warriors and a pretty great twist on the tired old love-triangle trope.

Six of Crows by Leigh Bardugo is the fantasy Heist novel you never knew you needed. It’s got criminals and bad boys and best friends, old gods and the fall of empires, magic and mystery, betrayal, all sorts of good stuff.

The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin is my favorite series of all time by my favorite author of all time. It’s a story where there is no good guys, only the heroism and monstrousness of deeply complex human beings who are struggling to survive in a world they themselves have created and destroyed. It’s about the evils of imperialsim, bigotry, and abuse. It’s about the extraordinary way humanity has of surviving a thousand apocalypses throughout our existance. It’s about a mother and her children and her past and her future. It’s about a traumatized girl with the world at her fingertips. It’s about rage and love and beauty and death and failure and survival.

The Diviners by Libba Bray is a Historic Fiction Mystery novel with queer kids, ghosts, murderers, cults, occultism, girls’ friendships, vice and virtue and coming of age in the era of Prohibition. It tells stories of kids getting caught up in more than they can handle and doing what little they can to protect each other, no matter what the world has to say about their worth or their place in it.

Now, if you’re in the mood for Non-fiction, I’m still here for you friend! Bear in mind, that when I recommend non-fiction books and think pieces, it’s not because I agree with everything put forward by them or think they’re right about what they’re talking on, but because I think that the persepctive from which they are discussing a topic is fascinating, or because I think that there is a great starting point for a fascinating debate or conversation within their suggestions.

Debt: The First 5000 Years by David Graeber is a fascinating perspective on the development of economic systems over the years. It talks about how the notion of debt as an economic force is both incredibly new and hilariously old. It demonstrates the different ways that debt appears throughout history, how the advent of paper currency and credit changed the entire economic layout despite the idea of one person owing something to another being a formative part of societal cohesion for millenia.

Sexual Features, Queer Gestures, and Other Latina Longings by Maria Rodriguez is a excellent book that touches on not just the history and cultural development of queerness within the context of Latinx culture, but also the part that disidentification plays in any queer person’s social development, let alone in the development of QPOC.

Travesti: Sex and Gender among Brazilian Transgendered Prostitutes by Don Kulick is an incredibly challenging opportunity to expose yourself to the critical truth that while queerness as a broader concept has the potential to unite people across infinite cultures and contexts, the reality is that every society has its own queer culture, its own history, it’s own definitions, its own reactions, its own needs. Travesti is the documentation of many lifetimes of stories, tradtitions, and experiences of a group of transgender women in Brazil whose lives are a complicated blend of issues from their gender, to their sexuality, to their profession, to their local communities, to the imperialism of the west over their homelands, to their own personal desires. Reading Travesti gave me the chance to see both the similarities and the differences in the way I grew up understanding my and my family’s queerness as opposed to how these women experience their gender and sexuality. It was a beautiful exploration of the ways in which many of us US queers take our perspective on these issues for granted, and the infinite diversity which we so often forget or intentionally hide from view.

And lastly, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection by Anna Tsing is the first book I read on the subject of the man-made nature of environmental disaster. It talks about how blatantly racist, classist, and imperialist the natural disasters of the modern century really have been, from towns primarily made up of POC being the homes of environmentally disasterous resource production, to the way that climate change so often affects the impoverished and colonized more devastatingly than it affects the imperial west. If I’m recalling correctly, it even goes into some discussion of the way in which capitalism, classism, and colonization have turned the fires that used to burn across my home state as a natural part of the life cycle of the region have now grown out of control as a direct result of the man made abuses that the powerful have made against the land and the less powerful people who live on it.

When I opened this ask, I giggled for so long that Hubby looked over and said “oh no, I wonder if they realize what they’ve just created” and I have to say, this question has tickled me pink and I am thrilled to have the chance to refer ya’ll to some of the most interesting reads I’ve had in the last five years or so. Please let me know if you end up liking any of these, as I always have more books like them to recommend, and also let me know if you have any specific kinds of books you want me to recommend to you as well. There are so many genres I didn’t get the chance to mention here!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text