#remember when everyone at my high school called me 'dirty jew' as some kind of silly petname for four years because of that show?

Text

to this day i am eternally baffled by the concept of south park fanart. like these are geometric shapes whose primary character traits are (checks notes) different flavors of racism who is out there going ouough yeah i wanna draw them all cute and kissign

#this is brought on because a former mutual on insta shared south park fanart to their story#needless to say we are no longer mutuals#loverboy wordz#remember when everyone at my high school called me 'dirty jew' as some kind of silly petname for four years because of that show?#i sure do. good times (heavy sarcasm)#i respect the zootpoia abortion comic artist more than i'll ever respect southpark fanartists

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you so much for writing such a detailed answer about NLMG🥰 I also really enjoyed the discussions about the novel, trying to understand things like why they never left the school etc. After reading reviews and ishiguro's statements, we came to the conclusion that he wanted to show a phenomenon (a part of human nature), which often happened in history, where people were forced to live in bad systems and just kept living in it. Also if you want to talk about HP, do it. I would love to know☺️

No, nonnie 🤧 thank you for asking! I LOVE talking books and I haven't really been able to since covid kicked me of my college campus.

But, yes! That was the same kind of conclusion we reached in my class! This refusal to leave because you don't know if leaving will put you in a better situation. There's this sense of fear that surrounds the uncertainty of what's outside the life you've been forced to live!

Continued under cut, because this gets L O N G

When nonnie reads the tags so you get to ramble some more 🥺💕

So, here's some things that you may have never known about Harry Potter and how J.K. Rowling showed that she was G A R B A G E even before letting the world know she was a terf :D! Watch me get attacked by the Potterheads oml

First things first, I'm mainly going to focus on some of the over-arching themes, because that's what we covered in class, but there's still plenty to talk about.

Let's start with the Durselys. Now, if you've only seen the movie, this fact gets lost, but in the novel, they are depicted as having blonde hair and blue eyes. Now, this may not seem like much of anything, but there's a really cool parallel between Harry Potter and Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre (another very thought provoking novel). Specifically in their openings. The Durselys are pretty much copy and pasted from the Bronte's Reed family. I'm talking looks and personalities. They're violent and always picking on little Jane (small, frail, dark hair, green eyes. Familiar description, yeah?) I'm like 62% sure that Jane gets called dirty because of her looks and how she doesn't fit the Aryan ideals (please note: when I say Aryan I mean the ideals that have come to be associated with Hitler's "master race" rather than the true background of the word). Hmmm it's almost like Harry also doesn't fit in because of something similar. Harry has Lily's eyes and his father's hair, a direct link to his magic background. Bold of you to assume that he didn't stick out like a sore thumb in the Dursley family just because. No. It's so we could have a PHYSICAL difference as to why Harry is looked down upon.

The Smelting stick :) oh you mean something that I did extensive research on? It's a symbol for Dudley's power in the house :) the historical connotations behind walking sticks shows us that they were more widely carried by those who were in high power and authority (think about how royalty wield scepters). As time progressed, they also were made into weapons, some even being equipped to conceal daggers and pistols. Now, Dudley's stick may not have been doubling as a knife, but we can ALL tell that Dudley is the real ruler of the house, even before getting his stick (possible penis imagery which adds another level of masculinity into the conversation. I promise if you ever study lit in an upper level course, everything is a penis). But by giving him the Smelting stick, Rowling is really just giving you affirmation that Dudley is the head of the household as he B E A T S Harry with it. (The same idea of stick = power can be seen with the Malfoy men. Lucius carries a walking stick which is then given to Draco my BABY in half blood prince because HE'S calling the shots, so to speak. Also are going to ignore that a 16 year old CHILD started a W A R? like come on. That's fucked up. I can and will write an essay on why Draco deserves way more sympathy than what he gets and I'm not just saying this because I love him. But back on topic)

Harry living under the stairs? That is literally showing how he is beneath everyone in the Dursley home and how they walk all over him. There's not much else to explore there ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

The Goblins at Gringots oho ho 👀 this one left me shook when I found out. They're supposed to be Jewish people. It plays very heavily into the anti-Semitic view that Jews are stingy and greedy. Also?? They work underground?? Which uhhh doesn't sit right with me now that I know what I do, but maybe I'm reading too much into things.

We all know the House Elves are literally S L A V E S employed by everyone's favorite school nonetheless 👀 but here's what really drives me bonkers about that. Rowling insists that they LIKE it. Dobby is the only one who gets out of the system and the others are essentially like "bitch why the FUCK do you wanna be free." But isn't it nice to get a little insight on what she thinks of slavery smh 😔 didn't Kanye say the same thing? About slavery being a choice or that they liked it or something?? Or am I just tripping?

N E WAY. Here's one of my favorite parts. DIALECT. I don't remember if this gets mentioned in the books, but I know it's in the films. So, if we put Ron, Draco, and my queen McGonagall all up next to each other and have them say the same thing, what the difference? Their dialect. They accent they have is directly linked to their social class. Ron has more of a cockney accent, which is used by working-class Londoners. It's essentially the Southern accent of Americans, so it's typically associated with being dumb, so it kinda fits that not only is Ron Weasley poor, he's also not the brightest. Say it with me friends. Classist. Draco has a posh accent, so he's rich and super smart but also kind of a brat, especially early in the series ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ McGonagall is Scottish. That accent is very desirable because it EXUDES class. So, it seems to make sense that one if the older, wiser characters gets to be Scottish.

I wish I could go on and on, but I don't remember everything we talked about?? There was a lot of stuff JUST on Hogwarts itself and the British private school system and the classism you can find rooted there, but I don't really remember it all?? There's things about the roots of last names, specifically Potter vs Malfoy and the whole Anglo-Saxon vs Anglo-Norman roots of their names and how it translates to class and their beliefs. I could go on for YEARS about why I can't stand Albus Dumbledore but this post is already massive 😩 so I really shouldn't.

Nonnie, thank you for letting me ramble on about all of this. I've missed talking about books. It's honestly something that I will always enjoy :') my brain just thrives off of underlying meanings 🤧

Tagging @nekxrizawa because sis wanted to get in on this discussion.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

no change in the weather (peter/paul, nc-17)

“You’re gonna owe me the rest of your life for joining the band. Just like I’m gonna owe you the rest of my life for letting me in. Whether you like it or not, that’s the way it’s always gonna be.” During the Farewell Tour, Peter confronts Paul.

Notes: Credit to @collatxral-damage for input on the initial rough draft and the necklace; without it I don’t think this fic would’ve been completed.

“no change in the weather”

by Ruriruri

It’s wild when he lets it hit him, just how long he’s known Paul Stanley. More than half the bastard’s life. He was still Stanley Eisen when they met, legally, at least, but he’d never been that to Peter. He’d introduced himself in front of Hendrix’s old studio as Paul, stuck out his hand nervously and smiled, there with his long, curly hair and flower-printed tee and jeans. Peter remembered being disappointed, and then just resigned. Paul told him later he was twenty, but he looked younger. He looked like a kid. It had been ten times worse during his actual audition, when Gene and Paul both walked into the restaurant he played at wearing the exact same hippie outfits as before.

“You guys just stay in the back, all right?” Peter had gestured, unnecessarily, to the clientele in their immaculate suits and ties. “They think you’re fruits.”

They think you’re fags would have been more accurate, but he hadn’t wanted to blow his own audition with an insult. Paul and Gene both knew it, anyway. Gene had kind of nodded and Paul had followed him over to the corner of the restaurant. Peter had played the set and that was it; he was in. He was in the band of a part-time cabbie and a schoolteacher. A band that didn’t even have a name yet. Didn’t even have a lead guitarist yet.

In five months, they’d gotten the name and the lead guitarist. Another five or so and they had the record deal, and then they were on the road. And by that time, he’d spent a stupid amount of time with that kid. Eaten the sandwiches he’d brought back from the deli on the way to band practice. Listened to him bitch and fret on the phone and in person, share his dreams in weird, furtive little bursts, as though Paul was always counting on a dismissal before he even got the words out.

“I used to have this fantasy,” he’d confessed once, late at night, after a show, “when I was real young. Like, shit, maybe eight or nine, I dunno.”

“That’s kinda young for fantasies. You find a dirty magazine or something?” Peter had taken another gulp of beer and sat up in the bed across from Paul’s, squinting at his face in the dim lamplight. They’d shared a girl just after the show, a pretty brunette undergrad. Showered together after she left, fooled around in there a little too long. Gone from smacking each other with washcloths to real stupid stuff. Jacking each other off as the shower ran, high off the excitement of the concert and the girl. Once they’d stepped out of the bathroom, with all the evidence washed down the drain, Peter had thought he’d feel awful about it, but he hadn’t. He still felt good and high and—secure, oddly secure.

“Not a sex fantasy, pervert.” There hadn’t been a blowdryer in the hotel room, so Paul was lying in bed with a towel wrapped tight around his hair. Every so often, he’d rearrange it and try to twist out a little more of the water. “Anyway, I’d be in the schoolyard and sitting up in some chair and all my classmates would be down beneath me, calling me King Paul.”

“That’s pretty screwed-up,” Peter said after awhile, and Paul had glanced away. “Who do you think you are, Joseph out of the Bible? You want everyone who ever picked on you worshipping you?”

“I didn’t say they picked on me.”

“You didn’t have to.”

There’d probably been plenty to pick on, from what Peter could see. Paul had been a bit fat and still was a bit effeminate, and he had a lisp that he kept trying to get rid of but couldn’t. Not that it took much for grammar school kids to start tormenting. But most people got over it. Peter had, or thought he had. Up until that night, he’d thought his and Paul’s rockstar ambitions came from the same place. They didn’t.

It should’ve been more of a wedge between them than it managed to be. From then on, they kept sharing girls and kept fooling around every so often. They didn’t discuss it. It didn’t mean anything. Peter would do it with Ace, too—Ace was wilder, warmer about it, but Paul, for all his shyness, was more consistent. Just something that took the edge off, something that felt a little more real than dressing up in bondage gear to play the drums four days out of every week.

About a year later came the Hotter Than Hell photoshoot. Lydia sitting nearly naked in his lap, soft and flirting as he’d posed with her. Paul laying ten feet behind him on that king-sized bed, uncharacteristically soused, head lolling like a rose on too thin a stem, just about ready to break. Just about ready to pass out. There’d been a couple guys on the set, too. One of them had been watching Paul, tossing out catcalls Paul was too drunk to do more than laugh at. Peter had laughed, too, at first, until the guy started to head toward the bed between shots, until the come-ons got nastier. Paul was still laughing then, completely oblivious, guileless as a kid, half-dangling off the bed as he tried scooting over to offer the guy some room.

Peter hadn’t seen anything else, but he’d heard Gene stomping over. Heard the thump as he shoved the guy off the bed and onto the hard studio tile. Twenty minutes later and the shoot was over and Gene had locked Paul in his own car, like he thought the pervert was going to drag him out bodily, and that was that.

Peter had felt a little sick, thinking about it. Even back then. He hadn’t stopped it. Been too damn stupid to think it’d get any farther than a kiss or a grope, at best. Only Gene had recognized the danger for what it was.

Afterwards, half-sober at best, Peter had tried to ask him about it. Maybe even thank him for it. Gene had just shrugged.

“Paul’s fragile.”

“Tell me about it. I’ve only been living in the same room with him the entire year.”

“You don’t understand.” Something in Gene’s expression had curdled. His voice was lower; there was an edge to it Peter didn’t recognize. “Paul can’t—handle things.”

Peter hadn’t pushed for any more of an explanation, for once. The look on Gene’s face told him enough. Christ, he’d never thought Gene had ever handled anything more traumatizing from a woman than a venereal disease. Thought all his stupid bravado about the girls he’d laid was only because he’d never really gotten any until the band got big. He hadn’t thought there was any more to it than that. Hadn’t wanted there to be any more to it than that.

But even Hotter than Hell’s more than twenty years on. Twenty-six years on, now, and Gene’s still up to all the old bullshit there anyway. Fidelity never did matter to him when he had Cher, when he had Diana, and it doesn’t matter to him now that he’s got two kids by a Playboy Playmate he won’t even give his last name to. No Coop, but he’s still getting the roadies to pick out chicks for him during the show. Huge-titted blondes that weren’t even alive during KISS’ prime. It’s like Gene thinks there’s a fountain of youth in being desired. Like hell he really is desired now—he’s just a bedpost notch they can brag about to their girlfriends later. Same as he ever was. Same as any of them ever were.

But Gene isn’t the only one. Ace has some drugged-out girlfriend that’s there often enough; otherwise, he’s got a groupie or two that he finds himself. He’s got computers set up in his hotel room, probably cameras, too, as if he’s going for one more hedonistic thrill. Ace used to seem indestructible. Even five, six years ago, he seemed indestructible, like maybe the Jendell bullshit wasn’t bullshit and he’d keep on and on and on, bouncing back from every wasted night. He’s faltering now. He’s really faltering now.

Paul, well. Paul’s in bad shape from all the stage stunts he’s still stupidly pulling. Probably back to gulping down white cross before shows just like he used to in the seventies. But for all his come-ons and preening onstage, he isn’t even trying to pull the girls into bed anymore. Just stalks off to his hotel room alone after concerts, barricading himself in like fucking Greta Garbo.

Paul’s wife used to drop by sometimes. She hasn’t this entire tour, and fuck, Paul honestly seems to think Peter doesn’t know why.

Paul seems to think Peter doesn’t know a lot of things. Par for the fucking course. When Peter calls him out on it, about the tour profits, the contract renegotiations—Paul dismisses him out of hand as smoothly as he would a journalist trying to get an angle. Gene isn’t any better about it, but it hurts worse, coming from Paul. Maybe because he didn’t used to be half this slimy. Maybe because he used to care.

Maybe because Paul still has something like a hold on him. Materially, anyway. God knows he hasn’t touched the guy for anything more than a handclasp or hug for the cameras in years, for all Peter’s certain Paul still thinks he’s worth fooling around with. No. Paul had had sort of a fascination with crosses, one he’d obliquely apologize for (“I think they look cool, guess that makes me a pretty lousy Jew”), whether Gene was next to him or not. They’d traded off a couple times, worn each other’s jewelry. Not just for photoshoots, but for going out in general. Paul swapping out the gold Star of David necklace he occasionally wore for one of Peter’s smaller crosses. Never the crucifixes, only the crosses. At some point Peter had just given one to him, out of convenience. The only reason he remembers is because Paul tried to put it on immediately and got the chain stuck in his hair. Peter’d had to help him free it. Doesn’t matter. Some little eighteen-karat necklace from the days they’d both drop thousands a month just on their wardrobes. Paul probably doesn’t even have it anymore.

It’s just as well.

He catches a glimpse of Paul behind him in the hallway one afternoon around noon. Paul glances his way, speeds up, then they’re walking together in silence, passing a couple stiff-suited businessmen on the way to the elevator. Paul pushes the lobby button, then looks over at him again, finger still hovering over the panel. Peter shrugs.

“Same.”

“Oh.” Paul pauses, resting a foot against the side of the elevator, all the way up against the metal railing. Has to be uncomfortable just holding that position, but Paul doesn’t flinch or even wobble. It’s like he thinks Peter has a camera at the ready for a photoshoot ten years too late to attract anybody. “You hungry?”

With Gigi back home, he’s been taking half his own lunches alone in his hotel room, not wanting to spend the meal listening to Paul bitch or Gene hit on the waitresses. Not wanting to see Ace drink himself to oblivion. He starts to shrug again, but Paul’s expression, weird and a little strained, keeps an outright no at bay.

“Wanna stop somewhere with me?”

The elevator dings before Peter answers. He keeps staring at Paul as the elevator descends, looking for some sign of deception. That smarmy, satisfied look he couldn’t erase while he was busy screwing him and Ace over. He can’t find it. The bags under Paul’s eyes are worse than usual. Eyeliner’s on, probably concealer, too. It’s just his mouth, pursed and crooked, giving him away now. Paul’s not trying to pull one on him right now. He’s just sad as hell.

“Yeah, sure.”

“Where do you wanna go?”

“I don’t care.” And then, seeing Paul’s deflated look as they get off the elevator, “Maybe something light like sandwiches.”

“There’s a bistro down the block. Gene said it was pretty good.” Paul digs a pair of sunglasses out of his pants pocket and puts them on.

“You’re pickier than Gene.”

“I won’t send anything back. Promise.”

“Like I believe that.”

“No, really, I won’t. Well, maybe if it’s really awful, but…”

They pass up the front desk on their way out. The girl behind it offers a cheeky little wave and a giggle that can’t be part of the five-star hotel experience at all. Paul lifts his hand idly and offers a smile, and Peter does, too, both speeding up their pace so she won’t have time to ask for a picture.

Maybe a picture wouldn’t have been such a bad thing to stop for. No one comes up to them the entire walk to the bistro. Peter feels a couple of stares from passerby, but none of the old excitable murmurs, those are-you-sures and it’s-them-it’s-them-I-swear. No screaming, sobbing high school girls trying to grab Paul by the arm like they thought he’d run off with them if they just tugged hard enough. No bodyguards following them around to keep fans in check. All the old ego boosts are gone except for the roar of the concert crowd.

Paul holds the door open for him at the restaurant. They have to seat themselves, a piece of normalcy Peter feels like he should resent, but he doesn’t. Peter barely glances at the menu before ordering a Reuben sandwich, fries, and a Sprite, while Paul yanks off his sunglasses and deliberates for five minutes over whether to get a half-sandwich, half-soup combo or just the soup. He ends up getting the lobster bisque instead.

“That’s really all you’re eating?” Peter asks as he passes the menus back to the waitress. Paul shrugs.

“I’m not that hungry.”

“First time in a long time.”

“What, me not being hungry?”

“No. You having soup for lunch.”

“It’s a bisque, be specific—”

“Are you going to have candy for dinner, too? Like you used to?”

Paul winces.

“God, I’m not that sentimental.”

“The hell you’re not,” Peter says, and he means it harsher than it comes out; instead, the words sound almost warm, almost fond. He can’t manage to call Paul out on his own nostalgia trips with any real rancor when he’s putting on the old greasepaint, too. “You used to eat, what, two rolls of Life Savers before concerts—”

“And a bag of Satellite Wafers for nutrition.” Paul stirs the bisque before taking a swallow. His nose wrinkles as Peter watches, but true to his word, he doesn’t send it back or even start complaining, just reaches across the table to get the pepper shaker. “Or maybe because they were about five calories a wafer, who knows? You can’t even get them anymore.”

Peter shifts a little in his seat. The Reuben’s just okay, nothing great, but the fries are fresh and smothered in grease. There’s that oily sheen radiating off them unapologetically in the dim lighting of the bistro. Miles better than the five-star shit Paul raves about. If he’s not careful, he’ll finish them off in another five minutes.

“I never ate all the Life Savers. Gene always got the cherry ones.”

“Does he even like cherry?”

“He likes getting his tongue red.” Paul takes another few spoonfuls of the bisque. Peter expects him to continue, to start a stupid tirade against Gene—they’re not the big buddies they used to be right now, as if Peter cares—but there’s nothing.

Nothing except that worn-down look on Paul’s face and that emptiness in those too-big, too-sad brown eyes. The girls used to go crazy for them, just nuts, but Peter had only ever been reminded of a droopy-eyed beagle. Without the Starchild façade perking them up, the comparison’s more accurate than ever.

It should be satisfying, Paul having a hard time. Should really make Peter feel vindicated for the hell he’s been through over the last decade, to see Paul really struggling to pull himself together. It’s about time Paul struggled for anything. A guy like him, so fucking sensitive and vain, stupid enough to believe his own hype even now. Greedy and spiteful enough to be sucking him and Ace dry for daring to ever quit the band. Berating him during practice like he’s just a hired gun, like he’s Eric Carr or Singer, those poor bastards. Enjoying knocking him down peg after fucking peg. It ought to feel great knowing Paul’s sinking faster and harder than he ever did, knowing he’s trying to crush Peter’s ego out of his own flat-out misery.

But every time Peter looks at Paul, he doesn’t feel satisfied or pleased or any of that shit, just hollowed-out and edgy all at once. Like he should do something—which is fucking stupid. There’s nothing he’s ever been able to do for Paul. Not in twenty years at least. Paul doesn’t want anything from him, either, except a series of servile yeses and contract signatures and a drumming ability his destroyed arms can’t manage. Paul’s never wanted anything from him that Peter could offer up.

Peter’s tapping his fingers against the table before he realizes it. At first Peter doesn’t think Paul notices, either, until he feels his eyes on him.

“You okay?”

“I’m fine.” A breath, then, quiet, abrupt—“You better go easier on yourself sometimes, Paul.”

“I can’t.”

“You should,” Peter says, insists, weirdly, and then he shoves the basket of fries towards Paul’s side of the table.

He’s not positive why he’s done it. He doubts Paul will do anything but push them back. Wouldn’t be the first time. Paul’s piss-poor relationship with food is just like everything else in his life, all about control and a desperate need for approval. He’d starve if he thought it’d make one more chick in the audience think he was attractive. Eat an entire cake if that same girl told him he looked good doing it. No real sense of self, just a still-pretty face Peter shouldn’t give a damn about anymore.

Paul’s expression shifts slightly. He doesn’t look quite as blatantly miserable there for a second, as he reaches out his hand—black nail polish chipped, knuckles ragged—and takes a fry from the basket. Hesitates, eats it carefully, like it’s something delicate—and then he puts a hand on the basket, about to push it aside.

“Paul, c’mon, it won’t kill you. Lose any more weight and you’re gonna need those suspenders.”

“Pete, I can’t—”

“Sure, you can,” and Peter reaches over and takes another fry, holding it up a few inches from Paul’s mouth.

To Paul’s credit, he doesn’t glance around the restaurant, or snap at Peter to cut that shit out. Maybe even he realizes nobody’s looking. His fingers curve on top of Peter’s—no wedding ring—and he leans in, tugging the fry out of Peter’s grasp with his teeth and tongue, and eats it. There’s the quick flick of Paul’s tongue against his skin, brief enough Peter almost wouldn’t have noticed if it weren’t for that glint in Paul’s eyes. That sudden eagerness. Just like he’s found an advantage to press. Just like one of their old impromptu photoshoots. The effect isn’t the same on a dozen different levels, but something too-familiar and raw coils up in Peter’s stomach anyway. He starts to move his hand down, but Paul catches his wrist before he can manage.

“You gonna give me another?”

“Quit fucking around, Paul.”

“I’m not fucking around.”

“You are. Knock it off.” Peter yanks his hand back. Paul lets him.

“I—” Paul falters. He looks a little hurt, bewildered, maybe, which is strange to watch. He almost looks like he’s about to apologize, which is even crazier, but then his lips purse tight and he snatches a sudden, awkward fistful of the fries. Then he pushes the basket back with his other hand.

They don’t talk much after that. Paul makes some halfhearted conversation about Gigi, asking when she’ll be back by. When Jenilee’ll be back by. Peter barely answers, just eats the rest of the Reuben as Paul finishes off the fries he took. The only real discussion they have is over the check.

“I’ve got it.”

“No, I’ve got it. I invited you out.” Paul’s already thumbing through his wallet. Peter catches a brief glimpse of the plastic-covered photos inside, and he’s vaguely surprised to see Evan and his niece Ericka in there instead of Starchild. Evidence of Paul’s basic humanity’s been just that lacking lately. Paul pulls out a twenty and a five, sticks them on top of the bill, and stands up. “You coming back to the hotel?”

“Got nowhere else to be.”

“Sure? We’ve got six hours before they want us at the stadium.”

Almost thirty years of knowing him, and Paul still doesn’t want to go anywhere alone. The guts that made him eager to sing to twenty thousand people a night, paired with an anxiety that crippled him out of being able to do basic fucking things like sit in a restaurant by himself. Probably still does. Probably exactly why he even invited Peter along.

“I’m still heading back. You go off if you want.”

“No, I’ll head back, too.” And it’s confirmed, no matter what Paul says next to justify it. Peter’s just another prop to stave off his own pitiful lonesomeness. “I mean, there’s nothing really here to see.”

---

The walk back from the bistro isn’t as quiet as the walk there. A couple passerby stop them for autographs and they pose for all of one photo before getting back inside the hotel. The attention perks them both up, briefly, especially Paul, and they’re talking again on the way to the elevator.

“That last girl was really looking at you, Pete.”

“She was looking at both of us, c’mon.”

“No, no, it was you, I could tell.” Paul starts to smile. “She said she had your solo album.”

“I had four of those,” but Peter can’t manage much rancor over it. It feels a little too good to be wanted, however briefly. The concert crowd, fickle as it is, rarely compares to a gushing fan out on the streets.

“I’m just saying, she didn’t say she had mine. You could’ve had a real easy opening.”

“Yeah, twenty years ago. C’mon, Paul, I’m done with the groupie shit. So’re you.”

Paul blinks, then inclines his head and pushes the button for the elevator.

“Yeah.”

“Aren’t you?”

“I’m done with a lot,” Paul says shortly. For a second Peter almost wants to push it with him. Call him out on why Pam never comes around. Ask him if it’s the groupies from the last four years—or fuck, the last ten—or if it’s the escort services he used to patron on tour, or if it’s just too many years of breathing the same air as him that’s made her leave. It might be worth it after Paul’s stunt at the restaurant. It might really be worth it to see Paul’s expression crumple, except that’s not the crux of what’s bothering Peter, and it never has been.

“Done fucking me over?”

“What?”

That stupid doe-eyed look again. That twitch to Paul’s mouth as the elevator ascends like a ski lift.

“You know what I’m talking about.”

“Peter, what’ve I done—”

The elevator dings and they get off, Paul still giving him that look like he really has no idea at all. Peter speeds up, trying to force Paul to pick up the pace.

“You’re cheating me. I sign whatever the hell you want me to sign after I get my lawyer on it, and every month I get a fucking check that doesn’t even match the terms in the contract. Now explain that one.”

“It’s based on ticket sales, Peter, I explained that.”

“You didn’t explain shit.”

“You wanna look at numbers? I’ll get out whatever paperwork you want. The Reunion Tour was a flash in the pan. We won’t ever make that kind of money again.”

“Oh, you’ll make it. You’ll run this show straight into the ground just to get one more nickel.” Peter exhales. “I can’t take this shit anymore. You guys are fucking me at every turn.”

Paul stops dead in his tracks. Looks him straight in the eye and takes his arm. Peter’s too surprised to flinch or pull back as Paul leans in, right in the middle of the hallway, and kisses him on the mouth.

He hasn’t kissed him in years. Years. Peter’s mouth might as well be a plank of wood for all he responds to the still-familiar pressure. There’s no warmth to it. Paul’s eyes are closed and his hand’s squeezing Peter’s arm, but there’s no warmth to it at all, no pleasure, no want, even, nothing but meanness. By the time Paul pulls away, there’s a sick, choked feeling somewhere in Peter’s throat, almost a shakiness as he yanks his arm back, and then Paul’s got the nerve to spin another lie.

“Peter, I swear on my kids, there’s nothing going on.”

“The hell there isn’t,” Peter manages, shoving Paul aside and walking straight back toward his hotel room.

“Pete—wait—”

Paul’s following him. Peter can hear those stupid, clipped steps of his against the carpet, one more unforeseen product of wearing six-inch heels for over a decade. But Peter just quickens his pace, tugs out his keycard midstride and shoves it into the slot, satisfaction seeping through him as he slams the door right in Paul’s face. He doesn’t even wait for Paul’s knock before throwing open the minibar door and getting out a bottle of champagne, one he doesn’t even end up drinking. The sight of the label makes him think of Ace and how many braincells the poor bastard’s fried with every drop fizzing down his throat. Ace’ll be mush onstage soon if he doesn’t quit, and Paul won’t care, and Gene won’t care, as long as he can shudder through the solos. They won’t care at all.

He thinks, crazily, about pouring every single bottle down the sink. Paul and Gene can pay for it. Put it on their ever-expanding tab. Paul’s upcoming divorce is already on it. A minibar full of booze ought to be the least of their concerns.

He doesn’t do it. He doesn’t do anything, just lays on the bed for over an hour before he hears a knock at all. Long enough he’s sure it’s a cleaning lady, and doesn’t check the peephole before opening the door. He regrets it as soon as he’s gotten the door those first few inches open. There’s Paul.

He almost shuts the door. God only knows why he doesn’t. God only knows why he walks into the hallway and closes the door behind him, except to get the satisfaction of making Paul take a few steps back.

“Pete, look, come over to my room, we can go over everything. Whatever documentation you want. If I don’t have it, Gene will. I want to be fair with you.”

“I don’t want to hear it, Paul.”

“You just might. C’mon.”

“No.” Peter pauses. “No, you get in here.”

“But all the paperwork—” Paul starts.

“I don’t care. You meet me on my terms or you won’t meet me at all.”

Paul looks at him flatly. Disbelieving. As if Peter’s just throwing another fit for no good reason. As though Peter really is just a paranoid asshole, as though Paul’s some innocent angel. Peter’s pulse feels more like a battering ram pounding at his neck once Paul answers.

“It’s hotel rooms, Peter, what’s it matter to you?”

“You’ll do it or I’m cutting out. You can get Singer back and wave goodbye to half your fucking ticket sales.”

Paul starts to laugh.

“You can’t pull that shit anymore.”

“No, you can’t afford for me to pull that shit anymore.”

“The fuck do you expect, Peter? You expect me and Gene to just bend over backwards for your whiny ass? You think it’s ’73 again? You think you can threaten to quit whenever you want and—”

“No, I don’t think that. I know that. And I think a guy who’s about to get divorced might wanna hold onto every dime he—”

Paul grabs the door handle to Peter’s room. Yanks it, pointlessly. Peter tries not to snort as he pulls the card key out of his pocket and unlocks the door, tugging it open for Paul to come in first. He does, immediately shoving aside the phone and alarm clock from the nightstand to lean up against it. Peter just sits on the bed.

It’s plush in the suites. It has been ever since the Reunion tour four years back. Every hotel elegant to the point of being uncomfortable. Themed rooms—not tacky Vegas shit, either. Jacuzzis. Gene had told Peter at some point over dinner, a month or two ago, that it’d been Paul’s doing.

“He doesn’t think we’ll feel big in Ramada Inns,” he’d said, almost embarrassed. None of that interview-ready self-assurance. Weird as hell to see Gene acquiesce to any of Paul’s bullshit instead of brush it off.

“We didn’t need a ritzy hotel to feel big twenty years ago. We were big.”

Gene had shrugged.

“It’s perception. Maybe he’s right. Elvis wouldn’t have done a farewell tour and come back to a Motel 6.”

“Elvis had the dignity to keel over first,” Peter muttered, and Gene had laughed, and laughed hard, enough that he almost choked on a bite of one of the cookies he’d ordered for dessert. The conversation hadn’t eased Peter’s mind much, still certain at least half the star treatment was just another means to placate him and Ace while cheating them both. The other half was just feeding rotten egos.

The soft, yielding mattress might as well be concrete for how comfortable he feels sinking down onto it. Peter almost expects Paul to snap at him immediately, but at first, he’s just standing there against the nightstand, hands behind him, curling over the table’s edges.

“You got me in here. Congratulations. You going to rail me out over your contract? Complain about how fucking unfair it is that you’re not getting a quarter-share of everything? Go ahead. I’ve heard it the last four years, but go ahead. Maybe it’ll wear a little better now, who the fuck knows. What do you want, Peter? I’m all ears.”

“I just bet you are.”

“Fuck you.”

“You wanna know what I want?” Peter’s voice sounds weird even to him, close to throaty. Nerves all stretched out, taut and tight as piano wire. “I want a bandmate instead of a dictator. I want to share the stage with somebody I can stand to be around. But that ain’t happening. I guess I’d be better off asking for my quarter-share.”

“Don’t try to play me—”

“Then don’t you ever fucking kiss me again unless you mean it.”

Paul just stares at him. He looks almost as though he’s about to laugh, his mouth twitching up for a second or two, and then he shakes his head.

“That’s what this is about? Really? God forbid I get my mouth on you anymore. I guess once you’ve got a good Christian girl you’re done fucking Jews—”

“I haven’t fucked you in years.”

“Nah, you’ve just fucked me over.” Paul does laughs then, throatily. “You say I’m the one doing it when it’s been you the whole time. You and Ace and Gene. You all jumped ship the second you got tired of it. The second KISS wasn’t fun anymore.”

“I didn’t jump ship—”

“Decided you’d rather play house and do coke than play the fucking drums. Right before we were set to tour—but that’s fine. Doesn’t matter. Ace quits. We lose fifteen million. That’s fine. That doesn’t matter. Just me and Gene, right? Like you thought we always wanted, right?” Another laugh. “I didn’t ever want that.”

“You sure as hell gave off that impression.”

“I didn’t want it. I wanted a team, I wanted the four of us. I thought we were gonna be like the Beatles. Like they were in the movies. I really thought—I was a kid, I bought into it. I thought they really did stay all together in the same damn house and—” He cuts himself off, shaking his head. “I was so naïve, I…”

“A team stands up for each other. I don’t remember you doing a whole lot of that when Ezrin—”

“I’m not talking about Ezrin. I’m talking about the band. Or what was left of it.” Paul shifts against the nightstand, yanking a hand through his hair. “You think we were still living it up after you quit. I don’t know what the hell ever gave you that idea.”

“Must’ve been all those gold albums.”

“Yeah, all two of them.” Paul snorts. “Lucky we even got that many. Gene fucking off to Hollywood was the last straw. Left me holding the bag for everybody. Found out if I wanted a record made, I had to pull the whole damn thing together myself. Like the solo albums all over again, except nobody was in line begging to collaborate anymore. I got fucking front-row seats to watch KISS turn into the biggest joke in the industry. I had to beg on my hands and knees just to get the band on MTV. And meanwhile you still got your nice quarter-share of all my work. You got that for eight fucking years after you quit. Just right out there for you.” Paul takes a breath. His voice is starting to crack. “Then you’ve got the nerve to say you want anything out of me. You don’t deserve what you’re getting out of me.”

“You want me to feel sorry for you, Paul? Is that it?”

“Please, the only person you’ve ever felt sorry for in your whole life is yourself. I know you couldn’t give less of a shit.”

“That’s a lie. If I didn’t give a shit, I wouldn’t still be touring with you.”

Paul’s expression starts to twitch. Then it hardens back up right like it used to, when an insult cut a little too close, like every insult did, and his mouth tightened and he’d be sniping for the next half-hour. He starts to say something, but Peter cuts him off before he can.

“I wouldn’t tour with you, I wouldn’t eat with you, I wouldn’t even talk to you.” Peter exhales. “But I do. I owe it to you. And you owe me something, too.”

“Don’t act like you’re such a martyr for wanting a paycheck,” Paul snaps out. “What do I owe you for? ‘Beth’? You still get your royalties—”

“Not ‘Beth.’ It ain’t that simple.” Peter’s hands are sweaty against the covers. “You’re gonna owe me the rest of your life for joining the band, Paul. Just like I’m gonna owe you the rest of my life for letting me in. Whether you like it or not, that’s the way it’s always gonna be.”

“I don’t owe you a goddamn thing. I don’t—” Paul pushes forward from where he’s been leaning against the nightstand. His eyes are glassy, that strange, haunted look making every curve and jut of his face seem like it’s carved from alabaster. It’s only when Pete feels a tug on his sleeve that he realizes Paul’s reached out a hand. “Come with me and I’ll prove it to you. I-I’ll make sure.”

He shouldn’t get up. He shouldn’t follow him. It’s going to be another attempt at robbing him of what’s his. Paul’s going to use the time it takes to get there to get his bearings and then he’ll really lay in on him, cut him up with surgical precision. Peter’s never going to get the contract fixed. He’s never going to get the money he’s owed. He’s never going to get that flowerchild wannabe back again, that shy kid still propelled by a dream from when he was eight, that vulnerable, stupid kid who had to be protected. He’s gone now. He’s been gone for decades. Even the nightly stageshow’s just a parody of the Paul that Peter remembers.

But Peter does get up, and he does follow him. Not to some conference room like he expects. He doesn’t call up Gene or any lawyers or Doc. Paul just takes him four doors down to his hotel room, lets him in.

Inside, it’s the same bland opulence as in his own suite. The same “Welcome, KISS” banner from the hotel next to the full-length mirror. A made-up, empty bed. No printouts or laptops. Paul hasn’t gotten any business materials out at all. Paul heads straight for the vanity, pushing away a small stash of makeup and creams as Peter watches. It’s a second or two before Paul’s hand closes around a small velvet box, pops it open, and he pulls something out and pushes it into Peter’s palm.

“There. That’s all. You wanna renegotiate the contract, talk to Gene. I’ll tell him to give you whatever you want.”

“Paul—”

“I don’t owe you. I don’t owe you, all right?”

Paul’s not looking him in the face now. His eyes are on the vanity table. Slowly, Peter opens his palm and looks down, confirming what he already knew he’d been given, the metal hard and cold in his hand. It’s nothing special. Eighteen karat gold. No tarnishes. No scratches. It’s the cross necklace he’d given Paul more than twenty years ago.

All of a sudden, Peter can’t lift his gaze from his own hand. His eyes are burning, and he’s far too aware of every breath pushing through his lungs. The cross glints in his palm, dangling heavy as an oath from its chain, and he can’t seem to close his fingers back around it. Can barely seem to speak.

“This is yours.”

“It’s not. It’s yours. I’m giving it back.” Paul still isn’t facing him, still staring at the vanity counter, fingers curved on its edge. He isn’t even looking at his own reflection in the mirror. “Y-you can go on now. I’ll see you at soundcheck.”

“Paulie.”

Paul stiffens up. Peter doesn’t see him do it, but he can tell, something in the way he shifts. He won’t ever get another chance. He knows it. Peter tears his gaze away from the necklace, fingers closing around the cross, and he takes a breath and says his name again.

“Paulie.”

Peter swallows and steps behind him. Paul doesn’t react at first. Peter almost expects Paul to start snapping at him, or pop off with some acidic comment to make him leave. Peter takes the chain between his fingers, cross dangling, as he drapes it over Paul. No wild mop of curls to brush forward anymore. He hesitates, watching Paul’s expression in the mirror, waiting for a sign that he should pull away, but Paul doesn’t move or shake his head or anything. His eyes are a little watery, and he’s biting his lip, but the rest of his expression’s blank up until Peter’s fingers brush against his collar as he closes the clasp. Then his lip starts to twitch and he turns around, bracing one hand against the counter.

“Pete—”

“It’s yours.”

Paul looks stunned. He reaches up to the necklace like he can’t believe it’s there. There’s something painfully nostalgic about watching Paul fingering that cross, watching a real moment of surprise sweep across his features. Reminiscent enough to almost hurt.

Peter’s sick of hurting. Now he knows Paul is, too.

His hand finds Paul’s shoulder a moment later, only to shift over to cup his cheek as he leans in, thumb dragging across his jaw. Peter can still feel the tension even as Paul inclines his head to meet his lips. Paul’s mouth against his is timid at first, almost afraid, for all that he’d kissed him so hard in the hallway. Peter has to ease him into it at first, like the steps to a half-remembered dance, fingers roving gently down from Paul’s face to the back of his neck.

They never did talk about it back then. What they liked. Just went in blind and laughed off the screw-ups. Paul was always headstrong with the groupies, all too willing to initiate, but shyer with him. Peter’s going off what he remembers and what Paul’s responding to, trying to be gentle without coddling, fervent without overwhelming. Trying to impart some meaning, some reassurance. It’s been so long, Peter forgot what a delicate, frustrating balance it is with him.

He almost doesn’t think it’s paying off, for all that there’s less caution to Paul’s kisses now, the brief swipe of Paul’s tongue against his lips. Peter parts them on automatic and Paul’s there, tongue darting lightly at first, then a little more urgently. He breaks off the kiss for a breath, hands shifting to rest on Paul’s shoulders, only to feel Paul get his arm around his waist and pull him in close, until they’re flush against each other. Then Peter knows Paul’s getting his bearings again, though feeling the start of Paul’s hard-on against his thigh is plenty, and flattering, evidence enough. It’s taking Peter longer to get there, but Paul seems determined, rocking against him steadily, groping and fondling his ass. Peter responds in turn, eager, pressing in hard, grinding their hips together, until Paul’s soft grunts turn into a groan.

“Pete, every time you do that, you’re knocking me against the vanity.”

Peter just grins.

“Then maybe we better move.” His grip tightens on Paul’s shoulders as he leads him towards the bed. Peter tries once to turn him around so his back’s facing the bed, but Paul doesn’t respond and so Peter doesn’t attempt it again, just lets Paul press him up to the bed, easing against him until he’s seated. Paul doesn’t seem half as nervous now, pushing kisses against Peter’s neck as his fingers work the button and zipper of his jeans, tugging them down just enough to free his cock.

“All this time and you’re still not wearing underwear.” Paul’s breath is warm against his neck, a hint of a laugh in his words.

“I wouldn’t even wear the cup, what makes you think I’d—nghh,” Peter trails off as Paul’s hand wraps around his dick. Twenty years and, unsurprisingly, Paul’s hardly out of practice at all, the steady rhythm of his fingers urging Peter to full hardness before long. But it’s Paul’s mouth driving him crazy, the way he’s leaning in, the hunger of each kiss. Peter returns it all eagerly, insistently, pressing tongue and teeth against the soft skin of Paul’s neck, not managing to stay there long enough to leave a real mark, while his hips push up with every pump of Paul’s hand, a hand that’s soon withdrawn. Peter’s about to complain when he realizes Paul’s sinking to his knees in front of him, rubbing his hands against his thighs. Peter puts his own hands on top of Paul’s, resting against his wrists.

“Paul, hey, you don’t have to—”

“I want to.” Paul’s hands shift beneath Peter’s, fingers rubbing circles along the seams of his jeans. “At least lemme get you worked up.”

“I’m pretty damn worked up as it is,” Peter retorts. Every second without some contact is making his arousal all the more distracting. Judging by the glint in Paul’s eyes, he knows it, too. Peter’s down; of course, he’s down. His uncertainty’s borne more out of concern for Paul’s comfort level than his own. If Paul’s pushing himself for the wrong reasons and they’re about to fuck each other up ten times worse. “You think you can handle it?”

Paul snorts.

“You’re gonna have to be more specific on where,” he says, and before Peter can respond with more than a laugh, Paul’s laving his tongue against his dick. Peter’s breath hitches, hands tightening around Paul’s wrists. Paul tugs meaningfully at his jeans, lets up for a second so Peter can pull them down further. They’re around his knees now, Paul roving his hands eagerly across his bare skin. Freshly shaven. The spandex costumes still won’t allow for anything less. “Either way, I got this. Don’t worry.”

“Okay.”

Paul starts in earnest, then. His mouth’s encircling his cock before too long, taking him in further and further, a hand closing over what he can’t fit inside his throat. The only performance Peter’s ever known Paul to stay quiet for, apart from those occasional soft hums, the vibration intense around his dick. He’s still adept as ever. It’s almost bewildering. It’s like the way he felt that first night when they all went backstage together and put the greasepaint back on again. How close it is. How much everything’s falling into place. Like the years are melting in front of him, time lapsing backwards if they’ll both just let it.

Peter closes his eyes briefly, his hands wandering from Paul’s wrists to his shoulders to finally his hair, fingers rubbing against his scalp. For all the time it took to get him here, Peter’s unraveling quickly, mumbling curses and groans, trying to resist the urge to move his hips as Paul’s throat constricts tight and wet around him. He’s starting to moan, watching Paul’s expression, simultaneously intense and dazed, and he has to force himself to tug his hair and get them both back to reality.

“If you wanna fuck today, you better stop now.”

There’s a pause, a lick to the underside of his cock, and then Paul slides his mouth off his dick with a wet pop.

“All right, all right,” he says after taking a few sharp breaths and clearing his throat, not bothering to wipe the spit from his face before standing up. Peter shoves his jeans the rest of the way down, kicking them to the floor, shifting to give Paul room to climb onto the bed. Onto him. Paul’s already stripping, peeling off his pants and boxers far too fast for it to be a show, to Peter’s relief. He’s watched enough of that over all their tours and even from the times they’d share girls. He’d never really done it for Peter. The only thing he's careful about is the necklace. Peter watches him carefully tuck it underneath his t-shirt just before tossing the shirt to the floor. Peter waits, expecting him to fumble with the clasp, but Paul doesn't, just heads to the bed, and Peter realizes, suddenly, warmly, that Paul's leaving it on.

They’re still showering together after the shows, the three of them, Gene still abstaining from the stupidest and longest-held of their concert rituals. The years haven’t been bad to Paul, but then, he hasn’t had quite as many. Hasn’t yet even hit fifty. Despite all the diets and workouts, Paul’s abdomen is softer when Peter runs a hand down his hairy chest, but that’s about the only appreciable difference. He doesn’t get a chance to pay too much attention. As soon as he’s helped Peter shuck off his own shirt, Paul’s all over him, none of the cautious hesitation from before, practically crawling into his lap. The cold metal of the necklace makes a shiver run down Peter’s spine when Paul presses his chest against his while he’s licking a long stripe against Peter’s neck, hard-on rubbing up against his stomach. Peter’s own erection is making him heady enough, half-afraid he’ll come from just their fooling around, but Paul’s almost desperate, hands everywhere his mouth isn’t. He’s toying with and sucking on Peter’s nipples the way he used to, leaving Peter panting, his dick aching painfully with every swipe of his tongue.

Paul only stops to rustle around in a drawer for the lube. At first Peter figures he’s overcompensating for earlier, but then he realizes that’s not it at all. Paul’s not trying to prove that old Lover persona right with the one person who’d never buy it. It’s just that every bit of contact, every touch of skin to skin is soothing and maddening all at once. It’s just that he’s longing, too.

Peter eases Paul onto his back after awhile, leaning over him, kissing him on the neck and cheek as he slicks himself up, starts to prep, Paul’s gaze on him feeling more intent than ever. He’d said he could handle it. God knows his mouth still could, the memory of it making Peter’s cock twitch anew, but he’s really not sure about the rest of him. Paul never complained about Peter’s dick being too much to take in the seventies, for what little that’s worth now. Paul grunts as Peter slips and crooks his fingers inside him, legs splayed, hips lifting up, urging him deeper. Peter feels the familiar, faint bite of short nails against his back, a sharp hiss of breath against his forehead as he keeps working Paul over, stretching him out further. He’s pleased that Paul’s moaning starts before Peter’s so much as rubbed his dick teasingly against his entrance.

“C’mon,” Paul urges, rocking up to meet thrusts Peter hasn’t even made yet. It’s flattering as hell, whether it’s for show or not. From the consternation in his expression, the sweat beading on his face and chest, Peter doesn’t think it is. He can’t argue with the plea, can’t tease further when he’s wanting it so badly himself. Before long, Peter’s entering him, slow at first, getting him accustomed. Erasing the separation between them. Trying to. Paul fidgets beneath him, a little quieter once Peter’s fully inside him—and maybe that’d worry Peter more, if he wasn’t starting to smile, if his fingers hadn’t gone from digging into Peter’s back to rubbing his shoulder in a warm, encouraging rhythm. But Peter can’t help but ask anyway.

“You’re okay, yeah?”

“Yeah.” A wry pause. “I mean, you could give me a hand here—"

Peter barely swallows a laugh, wrapping his hand around Paul’s dick, trying to time each thrust with the pump of his hand. The pace is inconsistent despite his best efforts, but Paul doesn’t seem to mind, cock already throbbing, precum long since dripping from the tip.

After all the desperation from earlier, it doesn’t take much for either of them. Peter’s breathing gets harder and harder, curses and groans bleeding back into Paul’s name as he feels his orgasm approaching. Paul beats him to it, but barely, spilling into his hand with a sharp cry and a shudder, hand going lax at his shoulder, dilated eyes sliding shut. That’s nearly all it takes for Peter. Sweat’s dripping from his face, his hair, onto Paul and the bedsheets both as he manages another thrust or two before coming inside him.

He practically collapses against Paul in the aftermath, and he doesn’t pull out straight away. Stupidly, he doesn’t really want to. He feels way too—whole, odd as that seems. This hasn’t buried everything. Twenty years of hurt can’t disappear in one afternoon. Not for either of them. But it’s a start. It’s a start. It’s like something’s coming back to him. Like someone’s coming back to him. Like he understands now, that maybe things are finally going to be all right between them, maybe even great, maybe even grand. He could believe that now. He really could. All the more with Paul’s arms clasped tight around him as he murmurs quietly in the afterglow, the rise and fall of his chest against Peter’s the best tempo he’s felt in years.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arplis - News: I had known him almost all my life, Beniek

He lived around the corner from us, in our neighborhood in Wrocław, composed of rounded streets and three-story apartment buildings that from the air formed a giant eagle, the symbol of our nation. There were hedges and wide courtyards with a little garden for each flat, and cool, damp cellars and dusty attics. It hadn’t even been twenty years since any of our families had come to live there. Our postboxes still said ‘Briefe’ in German. Everyone – the people who’d lived here before and the people who replaced them – had been forced to leave their home. From one day to the next, the continent’s borders had shifted, redrawn like the chalk lines of the hopscotch we played on the pavement. At the end of the war, the east of Germany became Poland and the east of Poland became the Soviet Union. Granny’s family were forced to leave their land. The Soviets took their house and hauled them on the same cattle trains that had brought the Jews to the camps a year or two earlier. They ended up in Wrocław, a city inhabited by the Germans for hundreds of years, in a flat only just deserted by some family we’d never know, their dishes still in the sink, their breadcrumbs on the table. This is where I grew up.

It was on the wide pavements, lined with trees and benches, where all the children of the neighborhood played together. We would play catch and skip ropes with the girls, and run around the courtyards, screaming, jumping on to the double bars that looked like rugby posts and on which the women would hang and beat their carpets. We’d get told off by adults and run away. We were dusty children. We’d race through the streets in summer in our shorts and knee-high socks and suspenders, and in flimsy wool coats when the ground was covered in leaves in autumn, and we’d continue running after frost invaded the ground and the air scratched our lungs and our breath turned to clouds before our eyes. In spring, on Śmigus-Dyngus day, we’d throw bucketloads of water over any girl who wasn’t quick enough to escape, and then we’d chase and soak each other, returning home drenched to the bone. On Sundays, we’d throw pebbles at the milk bottles standing on the windowsills higher up where no one could steal them, and we’d run away in genuine fear when a bottle broke and the milk ran slowly down the building, white streams trickling down the sooty facade like tears.

Everyone – the people who’d lived here before and the people who replaced them – had been forced to leave their home.

Beniek was part of that band of kids, part of the bolder ones. I don’t think we ever talked back then, but I was aware of him. He was taller than most of us, and somehow darker, with long eyelashes and a rebellious stare. And he was kind. Once, when we were running from an adult after some mischief now long forgotten, I stumbled and fell on to the sharp gravel. The others overtook me, dust gathering, and I tried to stand. My knee was bleeding.

“You alright?”

Beniek was standing over me with his hand outstretched. I reached for it and felt the strength of his body raise me to my feet.

“Thank you,” I murmured, and he smiled encouragingly before running off. I followed him as fast as I could, happy, forgetting the pain in my knee.

Later, Beniek went off to a different school, and I stopped seeing him. But we met again for our First Communion.

The community’s church was a short walk from our street, beyond the little park where we never played because of the drunkards, and beyond the graveyard where Mother would be buried years later. We’d go every Sunday, to church. Granny said there were families that only went for the holidays, or never, and I was jealous of the children who didn’t have to go as often as me.

When the lessons for the First Communion started, we’d all meet twice a week in the crypt. The classes were run by Father Klaszewski, a priest who was small and old but quick, and whose blue eyes had almost lost their color. He was patient, most of the time, resting his hands on his black robe while he spoke, one holding the other, and taking us in with his small, washed-out eyes. But sometimes, at some minor stupidity, like when we chatted or made faces at each other, he would explode, and grab one of us by the ear, seemingly at random, his warm thumb and index finger tightly around the lobe, tearing, until we saw black and stars. This rarely happened for the worst behavior. It was like an arbitrary weapon, scarier for its randomness and unpredictability, like the wrath of some unreasonable god.

This is where I saw Beniek again. I was surprised that he was there, because I had never seen him at church. He had changed. The skinny child I remembered was turning into a man – or so I thought – and even though we were only nine you could already see manhood budding within him: a strong neck with a place made out for his Adam’s apple; long, strong legs that would stick out of his shorts as we sat in a circle in the priest’s room; muscles visible beneath the skin; fine hair appearing above his knees. He still had the same unruly hair, curly and black; and the same eyes, dark and softly mischievous. I think we both recognized the other, though we didn’t acknowledge it. But after the first couple of meetings we started to talk. I don’t remember what about. How does one bond with another child, as a child? Maybe it’s simply through common interests. Or maybe it’s something that lies deeper, for which everything you say and do is an unwitting code. But the point is, we did get on. Naturally. And after Bible study, which was on Tuesday or Thursday afternoons, we’d take the tram all the way to the city centre, riding past the zoo and its neon lion perched on top of the entrance gate, past the domed Centennial Hall the Germans had built to mark the anniversary of something no one cared to remember. We rode across the iron bridges over the calm, brown Oder river. There were many empty lots along the way, the city like a mouth with missing teeth. Some blocks only had one lonely, sooty building standing there all by itself, like a dirty island in a black sea.

We didn’t tell anyone about our escapes – our parents would not have allowed it. Mother would have worried: about the red-faced veterans who sold trinkets in the market square with their cut-off limbs exposed, about ‘perverts’ – the word falling from her lips like a two-limbed snake, dangerous and exciting. So we’d sneak away without a word and imagine we were pirates riding through the city on our own. I felt both free and protected in his company. We’d go to the kiosks and run our fingers over the large smooth pages of the expensive magazines, pointing out things we could hardly comprehend – Asian monks, African tribesmen, cliff divers from Mexico – and marveling at the sheer immensity of the world and the colors that glowed just underneath the black and white of the pages.

This is where I saw Beniek again. I was surprised that he was there, because I had never seen him at church. He had changed.

We started meeting on other days too, after school. Mostly we went to my flat. We’d play cards on the floor of my tiny room, the width of a radiator, while Mother was out working, and Granny came to bring us milk and bread sprinkled with sugar. We only went to his place once. The staircase of the building was the same as ours, damp and dark, but somehow it seemed colder and dirtier. Inside, the flat was different – there were more books, and no crosses anywhere. We sat in Beniek’s room, the same size as mine, and listened to records that he’d been sent by relatives from abroad. It was there that I heard the Beatles for the first time, singing “Help!” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand”, instantly hurling me into a world I loved. His father sat on the couch in the living room reading a book, his white shirt the brightest thing I’d ever seen. He was quiet and soft-spoken, and I envied Beniek. I envied him because I had never had a real father, because mine had left when I was still a child and hadn’t cared to see me much since. His mother I remember only vaguely. She made us grilled fish and we sat together at the table in the kitchen, the fish salty and dry, its bones pinching the insides of my cheeks. She had black hair too, and although her eyes were the same as Beniek’s, they looked strangely absent when she smiled. Even then, I found it odd that I, a child, should feel pity for an adult.

One evening, when my mother came home from work, I asked her if Beniek could come and live with us. I wanted him to be like my brother, to be around me always. My mother took off her long coat and hung it on the hook by the door. I could tell from her face that she wasn’t in a good mood.

“You know, Beniek is different from us,” she said with a sneer. “He couldn’t really be part of the family.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, puzzled. Granny appeared by the kitchen door, holding a rag.

“Drop it, Gosia. Beniek is a good boy, and he is going to Communion. Now come, both of you, the food is getting cold.”

*

One Saturday afternoon, Beniek and I were playing catch on the strip outside our building with some other children from the neighborhood. I remember it was a warm and humid day, with the sun only peeking through the clouds. We played and ran, driven by the rising heat in the air, feeling protected under the roof of the chestnut trees. We were so caught up in our game that we hardly noticed the sky growing dark and the rain beginning to fall. The pavement turned black with moisture, and we enjoyed the wetness after a scorching day, our hair glued to our faces like seaweed. I remember Beniek vividly like this, running, aware of nothing but the game, joyous, utterly free. When we were exhausted and the rain had soaked through our clothes, we hurried back to my apartment. Granny was at the window, calling us home, exclaiming that we’d catch a cold. Inside, she led us to the bathroom and made us strip off all our clothes and dry ourselves. I was aware of wanting to see Beniek naked, surprised by the swiftness of this wish, and my heart leapt when he undressed. His body was solid and full of mysteries, white and flat and strong, like a man’s (or so I thought). His nipples were larger and darker than mine; his penis was bigger, longer. But most confusingly, it was naked at the tip, like the acorns we played with in autumn. I had never really seen anyone else’s, and wondered whether there was something wrong with mine, whether this is what Mother had meant when she’d said Beniek was different. Either way, this difference excited me. After we had rubbed ourselves dry, Granny wrapped us in large blankets and it felt like we had returned from a journey to a wondrous land. “Come to the kitchen!” she called with atypical joy. We sat at the table and had hot black tea and waffles. I cannot remember anything ever tasting so good. I was intoxicated, something tingling inside me like soft pain.

Our Communion excursion arrived. We went up north, towards Sopot. It was the sort of early summer that erases any memory of other seasons, one where light and warmth clasp and feed you to the absolute. We drove by bus, forty children or so, to a cordoned-off leisure centre near a forest, beyond which lay the sea. I shared a room with Beniek and two other boys, sleeping on bunk beds, me on top of him. We went on walks and sang and prayed. We played Bible games, organized by Father Klaszewski. We visited an old wooden chapel in the forest, hidden between groves of pine trees, and prayed with rosaries like an army of obedient angels.

In the afternoons we were free. Beniek and I and some other boys would go to the beach and swim in the cold and turbulent Baltic. Afterwards, he and I would dry off and leave the others. We’d climb the dunes of the beach and wade through its lunar landscape until we found a perfect crest: high and hidden like the crater of a dormant volcano. There we’d curl up like tired storks after a sea crossing and fall asleep with the kind summer wind on our backs.

On the last night of our stay, the supervisors organized a dance for us, a celebration of our upcoming ceremony. The centre’s canteen was turned into a sort of disco. There was sugary fruit kompot and salt sticks and music played from a radio. At first we were all shy, feeling pushed into adulthood. Boys stood on one side of the room in shorts and knee-high socks, and girls on the other with their skirts and white blouses. After one boy was asked to dance with his sister, we all started to move on to the dance floor, some in couples, others in groups, swaying and jumping, excited by the drink and the music and the realization that all this was really for us.

Beniek and I were dancing in a loose group with the boys from our room when, without warning, the lights went off. Night had already fallen outside and now it rushed into the room. The girls shrieked and the music continued. I felt elated, suddenly high on the possibilities of the dark, and some unknown barrier receded in my mind. I could see Beniek’s outline near me, and the need to kiss him crept out of the night like a wolf. It was the first time I had consciously wanted to pull anyone towards me. The desire reached me like a distinct message from deep within, a place I had never sensed before but recognized immediately. I moved towards him in a trance. His body showed no resistance when I pulled it against mine and embraced him, feeling the hardness of his bones, my face against his, and the warmth of his breath. This is when the lights turned back on. We looked at each other with eyes full of fright, aware of the people standing around us, looking at us. We pulled apart. And though we continued to dance, I no longer heard the music. I was transported into a vision of my life that made me so dizzy my head began to spin. Shame, heavy and alive, had materialized, built from buried fears and desires.

That evening, I lay in the dark in my bed, above Beniek, and tried to examine this shame. It was like a newly grown organ, monstrous and pulsating and suddenly part of me. It didn’t cross my mind that Beniek might be thinking the same. I would have found it impossible to believe that anyone else could be in my position. Over and over I replayed that moment in my head, watched myself pull him in to me, my head turning on the pillow, wishing it away. It was almost dawn when sleep finally relieved me.

The next morning we stripped the sheets off our beds and packed our things. The boys were excited, talking about the disco, about the prettiest girls, about home and real food.

“I can’t wait for a four-egg omelette,” said one pudgy boy.

Someone else made a face at him. “You voracious hedgehog!”

Everyone laughed, including Beniek, his mouth wide open, all his teeth showing. I could see right in to his tonsils, dangling at the back of his throat, moving with the rhythm of his laughter. And despite the sweeping wave of communal cheer, I couldn’t join in. It was as if there were a wall separating me from the other boys, one I hadn’t seen before but which was now clear and irreversible. Beniek tried to catch my eye and I turned away in shame. When we arrived in Wrocław and our parents picked us up, I felt like I was returning as a different, putrid person, and could never go back to who I had been before.

We had no more Bible class the following week, and Mother and Granny finished sewing my white gown for the ceremony. Soon, they started cooking and preparing for our relatives to visit. There was excitement in the house, and I shared none of it. Beniek was a reminder that I had unleashed something terrible into the world, something precious and dangerous. Yet I still wanted to see him. I couldn’t bring myself to go to his house, but I listened for a knock on the door, hoping he would come. He didn’t. Instead, the day of the Communion arrived. I could hardly sleep the night before, knowing that I would see him again. In the morning, I got up and washed my face with cold water. It was a sunny day in that one week of summer when fluffy white balls of seeds fly through the streets and cover the pavements, and the morning light is brilliant, almost blinding. I pulled on the white high-collared robe, which reached all the way to my ankles. It was hard to move in. I had to hold myself evenly and seriously like a monk. We got to the church early and I stood on the steps overlooking the street. Families hurried past me, girls in their white lace robes and with flower wreaths on their heads. Father Klaszewski was there, in a long robe with red sleeves and gold threads, talking to excited parents. Everyone was there, except for Beniek. I stood and looked for him in the crowd. The church bells started to ring, announcing the beginning of the ceremony, and my stomach felt hollow.

“Come in, dear,” said Granny, taking me by the shoulder. “It’s about to begin.”

“But Beniek–”

“He must be inside,” she said, her voice grave. I knew she was lying. She dragged me by the hand and I let her.

The church was cool and the organ started playing as Granny led me to Halina, a stolid girl with lacy gloves and thick braids, and we moved down the aisle hand in hand, a procession of couples, little boys and little girls in pairs, dressed all in white. Father Klaszewski stood at the front and spoke of our souls, our innocence and the beginning of a journey with God. The thick, heavy incense made my head turn. From the corner of my eye I saw the benches filled with families and spotted Granny and her sisters and Mother, looking at me with tense pride. Halina’s hand was hot and sweaty in mine, like a little animal. And still, no Beniek. Father Klaszewski opened the tabernacle and took out a silver bowl filled with wafers. The music became like thunder, the organ loud and plaintive, and one by one boy and girl stepped up to him and he placed the wafer into our mouths, on our tongues, and one by one we got on our knees in front of him, then walked off and out of the church. The queue ahead of me diminished and diminished, and soon it was my turn. I knelt on the red carpet. His old fingers set the flake on to my tongue, dry meeting wet. I stood and walked out into the blinding sunlight, confused and afraid, swallowing the bitter mixture in my mouth.

The next day I went to Beniek’s house and knocked on his door with a trembling hand, my palms sweating beyond my control. A moment later I heard steps on the other side, then the door opened, revealing a woman I had never seen before.

“What?” she said roughly. She was large and her face was like grey creased paper. A cigarette dangled from her mouth.

I was taken aback, and asked, my voice aware of its own futility, whether Beniek was there. She took the cigarette out of her mouth.

“Can’t you see the name on the door?” She tapped on the little square by the doorbell. “Kowalski”, it said in capital letters. “Those Jews don’t live here any more. Understood?” It sounded as if she were telling off a dog. “Now don’t ever bother us again, or else my husband will give you a beating you won’t forget.” She shut the door in my face.

I stood there, dumbfounded. Then I ran up and down the stairs, looking for the Eisenszteins on the neighboring doors, ringing the other bells, wondering whether I was in the wrong building.

“They left,” whispered a voice through a half-opened door. It was a lady I knew from church.

“Where to?” I asked, my despair suspended for an instant.

She looked around the landing as if to see whether someone was listening. “Israel.” The word was a whisper and meant nothing to me, though its ominous rolled sound was still unsettling.

“When are they coming back?”

Her hands were wrapped around the door, and she shook her head slowly. “You better find someone else to play with, little one.” She nodded and closed the door.

I stood in the silent stairwell and felt terror travel from my navel, tying my throat, pinching my eyes. Tears started to slide down my cheeks like melted butter. For a long time I felt nothing but their heat.

Did you ever have someone like that, someone that you loved in vain when you were younger? Did you ever feel something like my shame? I always assumed that you must have, that you can’t possibly have gone through life as carelessly as you made out. But then I begin to think that not everyone suffers in the same way; that not everyone, in fact, suffers. Not from the same things, at any rate. And in a way this is what made us possible, you and me.

__________________________________

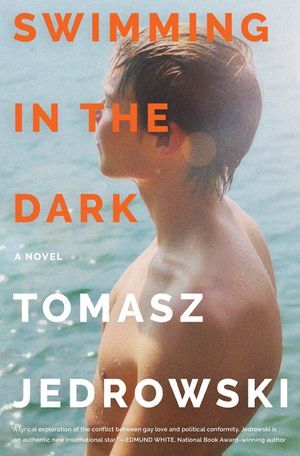

From Swimming in the Dark by Tomasz Jedrowski. Copyright © 2020 by Tomasz Jedrowski.Reprinted with permission of the publisher, William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

#FromTheNovel #WilliamMorrow #SwimmingInTheDark #FictionAndPoetry #Novel

Arplis - News

source https://arplis.com/blogs/news/i-had-known-him-almost-all-my-life-beniek

0 notes

Text

Testimony Time!

So here’s my testimony, kind of. :)

I’ve always been a roman catholic. “Wow” - you may say - “just another person born into a religious family trying to brag about how godly they’ve been living for this whole time!” Well no. Even though I’ve been baptized when I was 2 years old, and I went to Bible classes around the age of 10, I was far away from being a godly person.

So I quit Bible classes and going to church because of more reasons: a.) my teacher wasn’t the best. She was really intolerant when it came to terms of school work, which to be honest was far more important in my eyes. b.) We’ve moved to a different place, so our church was too far away and we simply didn’t make an effort to find a new one near us. c.) I was a ten-year-old... The last thing that interested me was religion and God and the boring Mass I had to go to every frickin’ Sunday morning... So yeah...

After that, I forgot everything I've learned about God...