#sometimes a marriage is to two people but also that's on antony for not realizing the extent of which marrying octavia was also marrying

Text

Plutarch, Antony (trans. Scott-Kilvert)

#wahoo#sextus pompey#ugh. technically. we're in the empire tag from my own chronology regarding how i split the timeline#however sextus pompey gets special rights. on account of being one of my favorites#SO! into the#roman republic tag#he goes!#komiks tag#drawing tag#ALRIGHT. we're done here. i was actually flipping through shakespeare's A&C earlier and turning around some thoughts about how#the antony-octavia marriage in that is actually four people. agrippa and octavian also.#and in turn i was like. well! the antony-octavian voyeurism-cuckold comic could in fact get worse! what fun!#unfortunately i took critical psychic damage @ the realization that if i drew it i would have TWO antony-octavian voyeurism-cuckold comics#that quite frankly the fact that i have already done one is Enough#on the other hand. i am considering thoughts about pompey and antony. intriguing dynamic. sextus is all teeth sometimes and i do like that

394 notes

·

View notes

Text

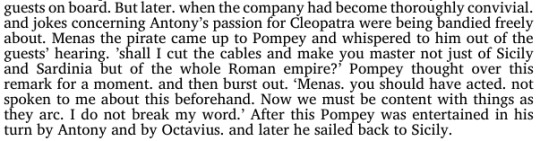

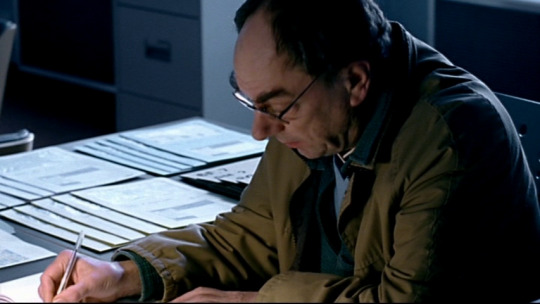

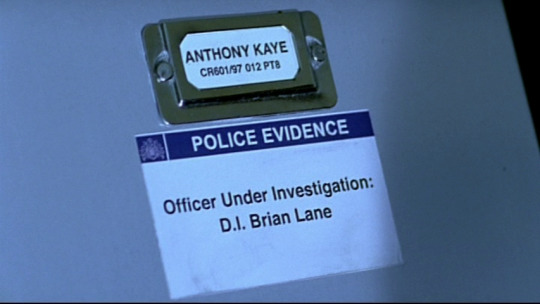

Personnel File: Brian Lane, Detective Inspector (ret)

JACK: “Ex-DI Brian Lane, Detective Superintendent Sandra Pullman.”

BRIAN: “Pullman. Sussex University, accelerated entry, 1987. Bramshill, ‘92. DI, Murder Squad, ‘92-’95. DCI, Armed Robbery Squad, ‘95 - ‘98.”

Our first introduction to Brian Lane, Detective Inspector (ret) shows us three key character traits about Brian: his photographic memory, his indifferent social skills, and his obsessions, but with detective work in general.

As a character, Brian most closely resembles the defective!detective trope in mystery fiction--or the brilliant but insufferable genius: he’s the Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot of the team.

His nickname is “Memory” Lane because his memory is really that good. He knows the record of every officer in the Met for the last thirty years. He apparently knows every crime and criminal in the files also. He’s a computer database but better.

He’s brilliant, and a brilliant detective (Jack says that he’s a “first-rate detective,” and coming from Jack, that’s the highest praise.) He works best by coming at puzzles from a different angle, by seeing patterns that no one else sees. The problem is, while he can see the most obscure patterns clearly, he can’t see the ones that are in front of his face.

It shows up most in the show with Esther, his long-suffering and loving wife, but it also shows up with the rest of the UCOS team. Brian misses social cues, has difficulty with conversations and manners that other people take for granted, has a need for certain rituals and patterns of stability in his life.

Esther is his cornerstone; Jack and the UCOS team are important supportive bricks. DO NOT TOUCH HIS DESK.

Brian specifically says that he has OCD, he’s a recovering alcoholic (sober 2 years, 2 months, 8 days as of the pilot.) And it’s strongly coded although never specifically spelled out that he may be on the autism spectrum.

In the pilot, he mentions both a car and grandchildren: in later episodes he doesn’t drive and has no children.

Brian is a deeply flawed but very appealing character. He is capable of deep friendship, loyalty, and generosity to the people he cares about--he can be extremely sensitive to other people’s feelings--but he can also be oblivious, selfish and a downright pain. He goes off on obsessive hobbies, and has terrible personal grooming habits. He doesn’t like wearing a suit, and likes wearing dress shoes even less. (It’s interesting to chart how “comfortable” Brian is by what he’s wearing.)

He’s depressed, obsessed, and paranoid (a paranoia that can become downright delusional when he isn’t on his medication), and the crux of his personal wounds are his guilt and regret over the man he let die in his custody.

There’s always been more to the story, he insists. And we desperately want to believe him. Part of his character arc over the seasons is watching him come to grips with, and grow from his mistakes. Jack’s a big part of that, but Esther, Esther is always his guiding light.

“Our customers?” He asks. Who are the Met’s “customers?”

Brian, like the other two old dogs, has a biting sense of humor (see his one-liner to Gerry in the Pill Scene: “Pale blue, lozenge shape. Well, you know what that’s for. Go on, it’s not hard.”). He’s also represents the third leg of the working class background: he’s made it half-way up the Met’s pecking order, but no further.

He’s an old-fashioned copper, out-dated and out of touch with policing methods, but not at all past his prime. In some ways, UCOS, with it’s stable environment and team connections makes him a better detective than he ever was with the Met.

“You mean, he did it, let’s prove he did it, then we can say we are not looking for anyone else in connection with this inquiry?”

Brian does his own fair share of techno-speak, but he can speak just as clearly and simply as Jack and Gerry. He has no guff with press-speak or police jargon.

ESTHER! Dear God, loving kind Esther, has been married to Brian for at least thirty years as of the pilot. She’s his anchor. With her, he falls to pieces, and no matter how oblivious or selfish he’s being, he really deeply cares about her. He loves her, and the best signs of how he loves her is how he tries to make himself a better man because she asks him to.

She’s worried about him rejoining the Force, even as a civilian. “Brian, I don’t want you doing this—for your own sake. Next time you might not just crack, you might break.”

But being a detective is his life’s work -- and being in UCOS gives him a chance to figure out how he was scapegoated for Antony Kaye’s death.

Yes, he is exactly that orderly.

Later on he will display his obsessive organization and memory to Sandra and Jack again:

“I’ve arranged the case evidence alphabetically. I’ve also listed it with the trial notes chronologically. That way you can cross-reference it more easily.”

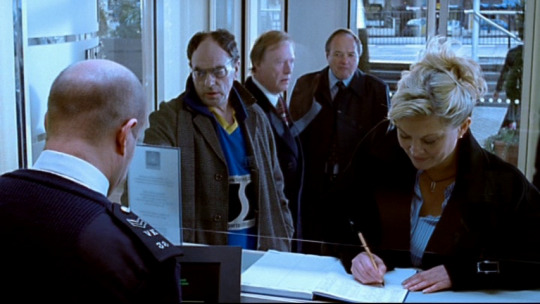

SANDRA: “I don’t suppose you know the contents of her stomach, do you?”

BRIAN: “Fish, peas, spinach. But no potatoes, which seems odd.”

The team will quickly get used to Brian knowing everything; it turns up as a plot point when he doesn’t.

Soon Brian will discover the marvelous world of computing, but not quite yet.

That is HIS coat hanger, and don’t you forget it. Brian doesn’t share easily. We learn later on that he has some good reasons for that, but for now we just think he’s a bit compulsive.

Yes, he does label his things.

Yes, Brian’s manners need some polishing. (Other fabulous one-liners in this scene: “Don’t smoke the filter, Mrs. Collard. I used to do that, now look at me.”)

Nice pocket knife, Brian.

“Corns, bad. Do you get them?”

“I don’t like public transport. I get people to give me a lift.”

Gerry, Jack and Sandra will spend a lot of time over the next decade giving Brian and his bicycle a lift.

Although Jack is about a decade older, Brian arguably has just as many health problems. It is vaguely suggested that he might be something of a hypochondriac--but it might just as easily be a side effect of the medication.

Brian takes pills for sciatica, lumbago, arthritis, rheumatism in his shoulder, as well as anti-depressants. In the pilot, he’s apparently only taking one medication for depression. By the next few episodes, Brian will start taking a lot more depression medication. It suggests that he had a pretty rough and tumble career as a police officer. At the time of Kaye’s death in 1997, he was having therapy for his depression.

Like all the men on UCOS, he carries a tape recorder and knows how to use it.

GERRY: “You know Jack, is he mad?”

BRIAN: “No. But I am.”

“He was black. Like you. Which automatically made things more difficult, more political. I found him face-down, having apparently choked on his own vomit. I was the arresting officer. I’d left him for less than two minutes, but no one else saw me in that time. I was being treated for depression. The Union advised me that I should submit a doctor’s report, pending the investigation. It wasn’t flattering. In fact, it basically said I was barking mad. Which gave the Met their get-out. Problem is, I think Antony Kaye was killed—and not by me. He was murdered inside that station. The Met are shielding someone, and I’m gonna prove it. Then we’ll see who’s mad, and who isn’t.”

Brian’s soliloquy in this part of the pilot is heartrendingly good. (Alun Armstrong’s performance is bravo.)

GERRY: “Isn’t it all just a bit busy inside your head?”

BRIAN: “There’s probably a lot more going on than in yours”

“Nobody touches this desk. Right? I’ll know if you have. AND my God is a jealous God and He shall smite thee severely.”

Brian loves Esther. It’s a marriage with its ups and downs, but Brian loves Esther. Full stop.

“I don’t break the law. I don’t smoke, I don’t drink, I take my medication. And you know what? My mind’s on fire.”

Brian has two loves: Esther and detection. One of those comes first.

“This DNA new forensics lark, makes our job easier, does it?”

Brian, hanging a lampshade on police work in the 21st century.

THE file.

Someday, we will know the truth of what happened; more importantly, Brian will, and will be at peace with himself. And the character growth of a decade will be complete.

JACK: “No, no you don’t. You only think you know what happened to him.”

(Jack’s right. Jack’s always right.)

BRIAN: “That’s why I left it at home.”

SANDRA: “Home?!? You brought evidence home?”

BRIAN: “How else was I gonna get it all filed?”

SANDRA: “You do realize that if they find out you did this, we’ll get crucified.”

BRIAN: “Why? Who’s going to tell them?”

They do things differently at UCOS. And Sandra, aside from realizing that she’s going to have to deal with a new kind of person in Brian, also realizes that he’s right. No one on UCOS is going to betray UCOS. That’s the loyalty and trustworthiness that will let Brian learn to grow and give back.

Brian, the big eater; Brian, with his silly napkin; Brian, who loves a free lunch.

Brian, with his toast.

Someday, sometime down the road, Brian will figure it all out, and be at peace. He’ll be a good husband to Esther, a good father and grandfather, and a good friend to Jack, Gerry and Sandra.

This time, he’ll know the truth, and leave on his own terms.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ravi Zacharias (1946 – 2020)

When Ravi Zacharias was a cricket-loving boy on the streets of India, his mother called him in to meet the local sari-seller-turned-palm reader. “Looking at your future, Ravi Baba, you will not travel far or very much in your life,” he declared. “That’s what the lines on your hand tell me. There is no future for you abroad.”

By the time a 37-year-old Zacharias preached, at the invitation of Billy Graham, to the inaugural International Conference for Itinerant Evangelists in Amsterdam in 1983, he was on his way to becoming one of the foremost defenders of Christianity’s intellectual credibility. A year later, he founded Ravi Zacharias International Ministries (RZIM), with the mission of “helping the thinker believe and the believer think.”

In the time between the sari seller’s prediction and the founding of RZIM, Zacharias had immigrated to Canada, taken the gospel across North America, prayed with military prisoners in Vietnam and ministered to students in a Cambodia on the brink of collapse. He had also undertaken a global preaching trip as a newly licensed minister with The Christian and Missionary Alliance, along with his wife, Margie, and eldest daughter, Sarah. This trip started in England, worked eastwards through Europe and the Middle East and finished on the Pacific Rim; all-in-all that year, Zacharias preached nearly 600 times in over a dozen countries.

It was the culmination of a remarkable transformation set in motion when Zacharias, recovering in a Delhi hospital from a suicide attempt at age 17, was read the words of Jesus recorded in the Bible by the apostle John: “Because I live, you will also live.” In response, Zacharias surrendered his life to Christ and offered up a prayer that if he emerged from the hospital, he would leave no stone unturned in his pursuit of truth. Once Zacharias found the truth of the gospel, his passion for sharing it burned bright until the very end. Even as he returned home from the hospital in Texas, where he had been undergoing chemotherapy, Zacharias was sharing the hope of Jesus to the three nurses who tucked him into his transport.

Frederick Antony Ravi Kumar Zacharias was born in Madras, now Chennai, in 1946, in the shadow of the resting place of the apostle Thomas, known to the world as the “Doubter” but to Zacharias as the “Great Questioner.” Zacharias’s affinity with Thomas meant he was always more interested in the questioner than the question itself. His mother, Isabella, was a teacher. His father, Oscar, who was studying labor relations at the University of Nottingham in England when Zacharias was born, rose through the ranks of the Indian civil service throughout Zacharias’s adolescence.

An unremarkable student, Zacharias was more interested in cricket than books, until his encounter with the gospel in that hospital bed. Nevertheless, a bold, radical faith ran in his genes. In the Indian state of Kerala, his paternal great-grandfather and grandfather produced the 20th century’s first Malayalam-English dictionary. This dictionary served as the cornerstone of the first Malayalam translation of the Bible. Further back, Zacharias’s great-great-great-grandmother shocked her Nambudiri family, the highest caste of the Hindu priesthood, by converting to Christianity. With conversion came a new surname, Zacharias, and a new path that started her descendants on a road to the Christian faith.

Zacharias saw the Lord’s hand at work in his family’s tapestry and he infused RZIM with the same transgenerational and transcultural heart for the gospel. He created a ministry that transcended his personality, where every speaker, whatever their background, presented the truth in the context of the contemporary. Zacharias believed if you achieved that, your message would always be necessary. Thirty-six years since its establishment, the ministry still bears the name chosen for Zacharias’s ancestor. However, where once there was a single speaker, now there are nearly 100 gifted speakers who on any given night can be found sharing the gospel at events across the globe; where once it was run from Zacharias’s home, now the ministry has a presence in 17 countries on five continents.

Zacharias’s passion and urgency to take the gospel to all nations was forged in Vietnam, throughout the summer of ’71. Zacharias had immigrated to Canada in 1966, a year after winning a preaching award at a Youth for Christ congress in Hyderabad. It was there, in Toronto, that Ruth Jeffrey, the veteran missionary to Vietnam, heard him preach. She invited him to her adopted land. That summer, Zacharias—only just 25—found himself flown across the country by helicopter gunship to preach at military bases, in hospitals and in prisons to the Vietcong. Most nights Zacharias and his translator Hien Pham would fall asleep to the sound of gunfire.

On one trip across remote land, Zacharias and his travel companions’ car broke down. The lone jeep that passed ignored their roadside waves. They finally cranked the engine to life and set off, only to come across the same jeep a few miles on, overturned and riddled with bullets, all four passengers dead. He later said of this moment, “God will stop our steps when it is not our time, and He will lead us when it is.” Days later, Zacharias and his translator stood at the graves of six missionaries, killed unarmed when the Vietcong stormed their compound. Zacharias knew some of their children. It was that level of trust in God, and the desire to stand beside those who minister in areas of great risk, that is a hallmark of RZIM. Its support for Christian evangelists in places where many ministries fear to tread, including northern Nigeria, Pakistan, South African townships, the Middle East and North Africa, can be traced back to that formative graveside moment.

After this formative trip, Zacharias and his new bride, Margie, moved to Deerfield, Illinois, to study for a Master of Divinity at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Here the young couple lived two doors down from Zacharias’s classmate and friend William Lane Craig. After graduating, Zacharias taught at the Alliance Theological Seminary in New York and continued to travel the country preaching on weekends. Full-time teaching combined with his extensive travel and itinerant preaching led Zacharias to describe these three years as the toughest in his 48-year marriage to Margie. He felt his job at the seminary was changing him and his preaching far more than he was changing lives with the hope of the gospel.

It was at that point that Graham invited Zacharias to speak at his inaugural International Conference for Itinerant Evangelists in Amsterdam in 1983. Zacharias didn’t realize Graham even knew who he was, let alone knew about his preaching. In front of 3,800 evangelists from 133 countries, Zacharias opened with the line, “My message is a very difficult one….” He went on to tell them that religions, 20th-century cultures and philosophies had formed “vast chasms between the message of Christ and the mind of man.” Even more difficult was his message, which received a mid-talk ovation, about his fear that, “in certain strands of evangelicalism, we sometimes think it is necessary to so humiliate someone of a different worldview that we think unless we destroy everything he holds valuable, we cannot preach to him the gospel of Christ…what I am saying is this, when you are trying to reach someone, please be sensitive to what he holds valuable.”

That talk changed Zacharias’s future and arguably the future of apologetics, dealing with the hard questions of origin, meaning, morality and destiny that every worldview must answer. Flying back to the U.S., Zacharias shared his thoughts with Margie. As one colleague has expressed, “He saw the objections and questions of others not as something to be rebuffed, but as a cry of the heart that had to be answered. People weren’t logical problems waiting to be solved; they were people who needed the person of Christ.” No one was reaching out to the thinker, to the questioner. It was on that flight that Zacharias and Margie planted the seed of a ministry intended to meet the thinker where they were, to train cultural evangelist-apologists to reach those opinion makers of society. The seed was watered and nurtured through its early years by the businessman DD Davis, a man who became a father figure to Zacharias. With the establishment of the ministry, the Zacharias family moved south to Atlanta. By now, the family had grown with the addition of a second daughter, Naomi, and a son, Nathan. Atlanta was the city Zacharias would call home for the last 36 years of his life.

Meeting the thinker face-to-face was an intrinsic part of Zacharias’s ministry, with post-event Q&A sessions often lasting long into the night. Not to be quelled in the sharing of the gospel, Zacharias also took to the airwaves in the 1980s. Many people, not just in the U.S. but across the world, came to hear the message of Christ for the first time through Zacharias’s radio program, Let My People Think. In weekly half-hour slots, Zacharias explored issues such as the credibility of the Christian message and the Bible, the weakness of modern intellectual movements, and the uniqueness of Jesus Christ. Today, Let My People Think is syndicated to over 2,000 stations in 32 countries and has also been downloaded 15.6 million times as a podcast over the last year.

As the ministry grew so did the demands on Zacharias. In 1990, he followed in his father’s footsteps to England. He took a sabbatical at Ridley Hall in Cambridge. It was a time surrounded by family, and where he wrote the first of his 28 books, A Shattered Visage: The Real Face of Atheism. It was no coincidence that throughout the rhythm of his itinerant life, it was among his family and Margie, in particular, that his writing was at its most productive. Margie inspired each of Zacharias’s books. With her eagle eye and keen mind, she read the first draft of every manuscript, from The Logic of God, which was this year awarded the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association (ECPA) Christian Book Award in the category of Bible study, and his latest work, Seeing Jesus from the East, co-authored with colleague Abdu Murray. Others among that list include the ECPA Gold Medallion Book Award winner, Can Man Live Without God?, and Christian bestsellers, Jesus Among Other Gods and The Grand Weaver. Zacharias’s books have sold millions of copies worldwide and have been translated into over a dozen languages.

Zacharias’s desire to train evangelists undergirded with apologetics, in order to engage with culture shapers, had been happening informally over the years but finally became formal in 2004. It was a momentous year for Zacharias and the ministry with the establishment of OCCA, the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics; the launch of Wellspring International; and Zacharias’s appearance at the United Nations Annual International Prayer Breakfast. OCCA was founded with the help of Professor Alister McGrath, the RZIM team and the staff at Wycliffe Hall, a Permanent Private Hall of Oxford University, where Zacharias was an honorary Senior Research Fellow between 2007 and 2015. Over his lifetime Zacharias would receive 10 honorary doctorates in recognition of his public commitment to Christian thought, including one from the National University of San Marcos, the oldest established university in the Americas.

Over the years, OCCA has trained over 400 students from 50 countries who have gone on to carry the gospel in many arenas across the world. Some have continued to follow an explicit calling as evangelists and apologists in Christian settings, and many others have gone on to take up roles in each of the spheres of influence Zacharias always dreamed of reaching: the arts, academia, business, media and politics. In 2017, another apologetics training facility, the Zacharias Institute, was established at the ministry’s headquarters in Atlanta, to continue the work of equipping all who desire to effectively share the gospel and answer the common objections to Christianity with gentleness and respect. In 2014, the same heart lay behind the creation of the RZIM Academy, an online apologetics training curriculum. Across 140 countries, the Academy’s courses have been accessed by thousands in multiple languages.

In the same year OCCA was founded, Zacharias launched Wellspring International, the humanitarian division of the ministry. Wellspring International was shaped by the memory of his mother’s heart to work with the destitute and is led by his daughter Naomi. Founded on the principle that love is the most powerful apologetic, it exists to come alongside local partners that meet critical needs of vulnerable women and children around the world.

Zacharias’s appearance at the U.N. in 2004 was the second of four that he made in the 21st century and represented his increasing impact in the arena of global leadership. He had first made his mark as the Cold War was coming to an end. His internationalist outlook and ease among his fellow man, whether Soviet military leader or precocious Ivy League undergraduate, opened doors that had been closed for many years. One such military leader was General Yuri Kirshin, who in 1992 paved the way for Zacharias to speak at the Lenin Military Academy in Moscow. Zacharias saw the cost of enforced atheism in the Soviet Union; the abandonment of religion had created the illusion of power and the reality of self-destruction.

A year later, Zacharias traveled to Colombia, where he spoke to members of the judiciary on the necessity of a moral framework to make sense of the incoherent worldview that had taken hold in the South American nation. Zacharias’s standing on the world stage spanned the continents and the decades. In January 2020, as part of his final foreign trip, he was invited by eight division world champion boxer and Philippines Senator Manny Pacquiao to speak at the National Bible Day Prayer Breakfast in Manila. It was an invitation that followed Zacharias’s November 2019 appearance at The National Theatre in Abu Dhabi as part of the United Arab Emirates’ Year of Tolerance.

In 1992, Zacharias’s apologetics ministry expanded from the political arena to academia with the launching of the first ever Veritas Forum, hosted on the campus of Harvard University. Zacharias was asked to be the keynote speaker at the inaugural event. The lectures Zacharias delivered that weekend would form the basis of the best-selling book, Can Man Live Without God?, and would open up opportunities to speak at university campuses across the world. The invitations that followed exposed Zacharias to the intense longing of young people for meaning and identity. Twenty-eight years after that first Veritas Forum event, in what would prove to be his last speaking engagement, Zacharias spoke to a crowd of over 7,000 at the University of Miami’s Watsco Center on the subject of “Does God Exist?”

It is a question also asked behind the walls of Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola Prison, the largest maximum-security prison in the United States. Zacharias had prayed with prisoners of war all those years ago in Vietnam but walking through Death Row left an even deeper impression. Zacharias believed the gospel shined with grace and power, especially in the darkest places, and praying with those on Death Row “makes it impossible to block the tears.” It was his third visit to Angola and, such is his deep connection, the inmates have made Zacharias the coffin in which he will be buried. As he writes in Seeing Jesus from the East, “These prisoners know that this world is not their home and that no coffin could ever be their final destination. Jesus assured us of that.”

In November last year, a few months after his last visit to Angola, Zacharias stepped down as President of RZIM to focus on his worldwide speaking commitments and writing projects. He passed the leadership to his daughter Sarah Davis as Global CEO and long-time colleague Michael Ramsden as President. Davis had served as the ministry’s Global Executive Director since 2011, while Ramsden had established the European wing of the ministry in Oxford in 1997. It was there in 2018, Zacharias told the story of standing with his successor in front of Lazarus’s grave in Cyprus. The stone simply reads, “Lazarus, four days dead, friend of Christ.” Zacharias turned to Ramsden and said if he was remembered as “a friend of Christ, that would be all I want.”

=====|||=====

Ravi Zacharias, who died of cancer on May 19, 2020, at age 74, is survived by Margie, his wife of 48-years; his three children: Sarah, the Global CEO of RZIM, Naomi, Director of Wellspring International, and Nathan, RZIM’s Creative Director for Media; and five grandchildren.

=====|||=====

By Matthew Fearon, RZIM UK content manager and former journalist with The Sunday Times of London

Margie and the Zacharias family have asked that in lieu of flowers gifts be made to the ongoing work of RZIM. Ravi’s heart was people.

His passion and life’s work centered on helping people understand the beauty of the gospel message of salvation.

Our prayer is that, at his passing, more people will come to know the saving grace found in Jesus through Ravi’s legacy and the global team at Ravi Zacharias International Ministries.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a confession: I followed your blog because I liked the URL ciceroprofacto. I soon realized your blog was about Alexander Hamilton and Not Cicero but your content is so good I couldn't unfollow... ANYWAY, I know Hamilton associated himself with Cicero- he called Burr the American Catiline at some point, right?- but there's some other parallels between them and I was wondering if you have any other stories/anecdotes/info about Hamilton's feelings on Cicero. Thanks, and I love your blog!

I also have a confession: I made up this username after questions about Cicero helped me qualify for the state certamen bowl as a team of myself. the username is a lie about the content here but I really am tight with Cicero as far as interests go.

But yes! Hamilton and Marcus Tullius Cicero: the comparison is striking.

Both were born in January, and despite having well-to-do fathers with good family names, were held back by their circumstances as youths. Cicero was born in Arpinum, a little over sixty miles south of Rome, Hamilton in Charleston, Nevis, separated from major hubs of the British empire. Both had one brother (though Cicero was the elder brother and Hamilton the younger), and both of their mothers were described as intelligent and thrifty. Both men were described as sickly boys, Cicero was semi-invalid and Hamilton frequently ill. In order to enter ‘cultured’ society, both men had to self-fashion themselves through studies of Latin and Greek, history, poetry, and philosophy.

For both Cicero and Hamilton, it was their talent as students and their ability to use rhetoric effectively that caught the attention of sponsors who facilitated their education. While they studied, both men met two friends they would keep lifelong correspondence with, Hamilton with Robert Troup and Hercules Mulligan and Cicero with Servius Sulpicius Rufus and Titus Pomponius.

Both men used military service (and public offices cursus honorum) to distinguish themselves and earn the connections and experience that would help them get careers in civil service. During their military service, both distinguished themselves as intellectuals, both credited as one of the most versatile minds of their generation.

After their stints in the military, both men immediately began careers as lawyers and statesmen in the public eye. Both were infamously effective orators. Cicero’s use of Latin rhetoric was so distinguished he changed the way people used the language. I don’t remember the exact quote, but it was said that prose in Latin and the romance languages up through the 19th century was either a return to his style and syntax or a reaction against it.

Both men were also inflammatory speakers. Cicero’s first major (and most famous) trial as a lawyer was in defense of a man named Sextus Roscius, and in the defense he presented, he challenged the dictator Sulla (whose army he had served in) by accusing some of Sulla’s political allies of having actually committed the crime. After that case, Cicero left Rome and spent some time in Greece studying philosophy and oratory (and I would liken this to Hamilton’s break with Washington, retirement from the military and study of law). Some historians speculate he had fled Rome because of the political threat, but that’s not proven.

Ironically, both men married up in their mid-twenties. Hamilton to Elizbeth Schuyler and Cicero to Terentia, of a plebeian noble house of Terenti Varrones. Both Eliza and Terentia were actively interested in their husbands political careers and sometimes helped them in their work. In both cases, there are traditional rumors that the men married for convenience and political ambitions, but both marriages lasted around 30 years through marital turbulence. The Reynolds affair in 1791 mirrors a stint in the 50s BCE where Cicero claimed Terentia had betrayed him and they briefly divorced and remarried (though I’m not sure about the reasons behind it).

Cicero returned to Rome shortly after completing that ‘higher education’ in Greece. And, like Hamilton, he entered politics and quickly rose through the ranks. Both men entered civil service posts that centered on the financial stability of their countries. Hamilton’s post as Secretary Treasury somewhat mirrors Cicero’s work as a Quaestor in Sicily though Hamilton’s work focused more on establishing the system of finance and Cicero’s focused more on rejuvenating and legitimizing a broken system. In Rome, 20 ‘Quaestors’ were elected each year to maintain the finances of a province with the Consul or Proconsul of that area. It was a big deal among the men on the cursus honorum to move along the ranks quickly, at the youngest age possible, and many tried to do so by bribing the electors and speculating from taxes. Cicero effectively did so by publicly ousting the other statesmen who did so with sharp oratory and accusations, thereby earning the trust and admiration of the voting male citizens, then canvassing and campaigning for his position.

Like Hamilton, Cicero was constantly shadowed by his lack of reputable ancestry, wealth, and birth. He was neither a noble nor a patrician and, having moved through the ranks by canvassing rather than consular ancestry, he was labeled a novus homo or “new man”. The last novus homo who had been elected consulate was a distant relative, Gaius Marius, who was politically radical and unpopular after Sulla’s ascension in the Roman civil war. Sulla’s reforms had strengthened the upper-class equestrian class, the optimates, and Cicero was an eques. More importantly, he was a constitutionalist, unable to side politically with the populares faction. Despite this, in each election, Cicero was voted first of all the candidates he stood against, most popular among all Romans except those of the poorest classes. Like Hamilton, Cicero held the strong centralized republican ideals of a gentry class that would never truly accept him despite his intellectual talents and personal charisma.

Hamilton did liken his feud with Burr to Cicero’s campaign against Catiline, though I would say Cicero’s conflict became much more serious while Hamilton’s was cut short by their duel and Burr’s public defamation. In 63 BCE, Cicero was elected Consul over Catiline, creating personal animosity between the two. In previous years, Catiline had sullied his own name with a series of crimes that took him to trial, between murder, speculation, and proscription. In a last-ditch effort to attain the consulship, he promoted universal cancellation of debts to draw the support of the lower classes and began talking his way into the support of men in the senatorial and equestrian rank who, after a political purge, had also become inviable candidates to public office for their own crimes (and men with good reason to dislike Cicero). After Cicero took office, he spent his time preventing Catiline’s conspiracy to overthrow him and the Roman Republic as a whole. He delivered four famous speeches, the Catiline Orations, that listed Catiline and his supporters’ crimes, and denounced his supporters as debtors. Catiline fled to Etruria after the first speech but Cicero delivered three more to prepare the Senate for a counterattack.Catiline planned to return with an army of veterans from Sulla’s military, peasant farmers and debtors. The supporters he’d left behind in the Senate worked to gain the support of the Allobgroges, a tribe of Gauls, but the Gauls delivered their letters to Cicero and the senate and Cicero was able to force the conspirators to confess their crimes. He had them taken to the Tullianum, the most notorious Roman prison, and strangled without formal trial.

We all know how Hamilton’s feud ended, and it’s hard to say what would’ve happened in his public life had he lived longer. Given how similarly Hamilton’s life seemed to match-step with Cicero’s, I imagine he would’ve managed to stir political conflict and eventually actuate his own death or ejection from the political field.

After his orations against Catiline, Cicero went on in his political career. He refused an offer of partnership with Julius Caesar, Pompey and Crassus, fearing it would undermine the Republic. After this Triumvirate rose to power, he was exiled by a law against anyone who executed Roman citizens without trial.He returned to Rome and resumed his involvement in politics about a year later, avoided supporting Caesar by leaving Rome with Pompey’s staff when Caesar invaded Italy in 49 BCE and tried to get his endorsement.He caught beef with Pompey as well and Cato, arguing with his commanders for their incompetence, returned to Rome and received a pardon from Caesar (fully planning to politically undermine his dictatorship with constitutional law whenever possible).He wasn’t involved in Caesar’s assignation but was supportive of it and became a popular leader afterwards. As Mark Antony carried out Caesar’s public will after his death, Cicero countered him politically and attacked him in public speeches, “the Phillipics”, calling the Senate against him. Cicero was wildly powerful with the public will and his supporters volunteered to take arms against Antony and his supporters. But, matters escalated, Antony continued military conquest and defied the senate, after he refused to lift the siege of Mutina, he was declared an enemy of the state. Cicero began a campaign to try and drive Antony out, even contacted Cassius, one of Caesars assassins, and alluded that Antony was a greater threat. But, it didn’t work and soon after Antony and Octavian allied with Lepidus, formed the second triumvirate, and began hunting their political rivals.Cicero, so publicly loved, was able to hide for some time, but he was caught in December 43 BCE in Formiae, trying to leave in a litter. He leaned his head out in surrender, decapitated in a gladiatorial gesture that bares the neck and makes the task easier. In the Roman tradition of oratory, hand motions are emphasized and characteristic. So, Cicero’s hands and (I’ve heard rumors of his tongue) were cut off and nailed on display on the Rostra in the Forum along with his head, the only victim of the Triumvirate to be displayed like that.

I don’t personally know of any anecdotes of Hamilton comparing himself to Cicero, but I do know he would’ve read and translated Cicero’s speeches and philosophies, and I can definitely see why he would feel a kinship with his life story. Here’s an article that discusses the allusion to Catiline.

tldr; Marcus Tullius Cicero and Alexander Hamilton were self-made men, “homines novi”, born in obscurity and rising quickly through the ranks of civil service positions through the merit of hard work, military service, and emergence into law. Despite this, and even as effective supporters of centralized constitutional power, they were both shadowed by their inability to completely fit in with the upper-class aristocrats. Both were gifted orators, political philosophers, and financial planners. Characteristically self-righteous, they both refused to back down from their core political beliefs, even when that placed their own lives at risk, leading to both their unparalleled political rise as well as their ultimate downfall.

#cicero#Roman history#answered#clodiuspulcher#I finally got around to answering this#I should be finding sources for things#that's just a lot rn

195 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are you able to explain Cleopatra Selene/Shimuka and your feels for them? and the possibilities? screwing over octavian sounds /amazing/

YES, I CAN, AND I LOVE YOU SO MUCH FOR ASKING.

Before I get started on this whole thing, I’m going to set up the premise, mostly because a lot of people don’t actually know who I’m talking about.

[Standard disclaimer: these people have been dead for millennia, and this means that a lot of dates have been fudged/guesstimated. Actual events/deaths are also shaky, which leaves us with this.]

Also, under a cut because this got long.

So, who were these two people?

Cleopatra Selene II was the only daughter of Cleopatra VII, last active ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt (before Rome took over), and Marc Antony. She married Juba II of Numidia and later became Queen of Mauritania.

Shimuka was the founder of the Satavahana dynasty- according to the Puranas, he was a servant to the then-ruler of the Kanva dynasty, but he overthrew the king, established his own rule, and went on to found a dynasty named, literally, “a hundred horses.”*

Now, we can start setting up the background:

Cleopatra had four children: one by Julius Caesar (Caesarion) and three by Marc Antony (twins, Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios; and another son, Ptolemy Philadelphius). Caesarion was her co-ruler.

Cleopatra Selene was born in 40 BCE.

In late 31 BCE, Cleopatra and Marc Antony lose the battle of Actium to Octavian. When it becomes clear that they cannot win against the might of Rome, Cleopatra sends Caesarion- her co-ruler- to India through Ethiopia.

In August of 30 BCE, Cleopatra and Marc Antony commit suicide.

The generals that Cleopatra sent with Caesarion betray him to Octavian; Caesarion never reaches India, and is killed.**

Cleopatra Selene and her two brothers are taken to Rome, clapped in chains, and forced to walk through the streets.

Between 26 and 20 BCE, her brothers die. The cause of death is unknown.

So what we know thus far is that Cleopatra Selene was ten years old when her parents died, ten years old when she was humiliated and forced to walk through the streets of Rome in chains. Sometime between ages fourteen and twenty, she saw the last of her family die.

The rest of her life, historically, goes roughly like this:

Octavian gives Cleopatra Selene a large dowry, and “ever after she was an ally of Rome.”

She marries Juba II of Numidia, and they settle in Mauritania.

Cleopatra Selene wields great influence over her husband, and under their leadership, Mauritania prospers.

She dies in early CE, in relative happiness.

We can now turn our attentions to Shimuka***:

Around 20-40 BCE, Shimuka overthrows the Kanva King and assumes the role of king.

The Puranas clearly state that he ruled for 23 years.

Shimuka also appears to be “a very shrewd politician”.

According to the same source, Shimuka married his son off to a maharathi’s (a very skilled warrior) daughter to get more support for overthrowing the Kanvas

Later in his reign, he went on to adopt/normalize Jainism

In the last years of his reign, Shimuka became a tyrant, and was deposed by his own brother.

(Here, I’m eliminating Satakarni- Shimuka’s son- from the narrative, because I like to imagine Shimuka as about 20-25 in this, and that means he can’t have a son of marriageable age. Just imagine that Satakarni is born a couple years later, to Cleopatra Selene.)

So, to sum up: Cleopatra Selene is a teenage girl who’s going to be given a huge-ass dowry, Shimuka is a newly-formed king who wants some form of legitimacy, and they live in ~roughly~ the same time period.

Is this not shipping material???

Now, okay, lbr, there need to be things exchanged for any such alliance to take place. Here comes the interesting part: the Satavahanas are sitting right on top of the Deccan Plateau, a place that is incredibly rich in minerals and crops.

They also have access to numerous ports.

Note that in the Geography of Strabo, Pliny the Elder asserts that “[he] learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to India, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise.” We can therefore assume that under Octavian’s rule, the Indo-Roman trade grew exponentially.

So let’s say that the Satavahanas were easier on tariffs than the Kanvas and eager for international trade. Let’s say that Shimuka realized that overthrowing a king and setting up your own rule is all well and good, but nobody really takes you seriously if you don’t get yourself some credibility. Let’s say that Shimuka wants gold, to finance an army that’s only growing in size, and he also wants legitimacy, to better-establish his dynasty.

Let’s say the Romans want better trade partners.

If, around 30 BCE, Shimuka overthrows the Kanvas and assumes kingship, this sets the stage for his eventual marriage. After negotiations and trade treaties- which can take years, not to mention that Octavian needs to legitimize his own rule first- Octavian’s persuaded to arrange an alliance between Rome and India, and what better way to do that than marriage?

Also, Octavian was a bastard. He deeply disliked both Cleopatra and Marc Antony. Though there is no evidence either way, it’s quite likely that he ordered the killing of Cleopatra Selene’s two brothers; he did order the death of Caesarion.**

The thought of sending Cleopatra’s only surviving child to the land where her heir was supposed to go but couldn’t… it’s deliciously ironic, and you can’t tell me that the man who decided to declare war on Cleopatra instead of Antony as a measure of revenge wouldn’t want that.

And now we get to the good stuff:

Cleopatra Selene, only living descendant of the Ptolemies, a dynasty that has been around for centuries, is asked to go to India, to marry a man who was, not less than a decade previous, a servant. She’s lost, in short order, her father, mother, and brothers, all within ten years. She’s alone.

And then she meets Shimuka, the man who overthrew his king in favor of his own kingdom, led by a revolution of servants- I mean, can you just imagine the debates on right and wrong these two would have, on monarchies and revolutions and military states and theocracies- because Shimuka follows Jainism, and Cleopatra Selene was born into a society where her mother was hailed as a goddess (Nea Isis).

In the beginning, of course, there are problems. Cleopatra Selene is haughty, dismissive, condescending; Shimuka is vulgar, violent, frightening. They don’t even speak the same language. But they have to find common ground, and Shimuka would likely be the one to take that step: Cleopatra Selene has the gold, after all, that’s financing his army, that he needs.

So they learn each other’s edges. Cleopatra Selene learns Prakrit, slowly, painstakingly; Shimuka finds her with a tutor and decides he’ll learn to read and write, too.

(Shimuka was a servant. He likely didn’t know how to read/write before this.)

(imo, in later years he asks her to do all the paperwork anyways, because she’s so much better at it. they’ve given each other that much trust, by then.)

They aren’t so different, these two; you see, Cleopatra Selene knows what it’s like to be nothing more than a glorified prisoner, because that’s what she was in Rome. Shimuka knows, intimately, what it feels like to be a servant.

Cleopatra Selene tells Shimuka how to defame his rivals and enemies without being ham-fisted about it, because she’s watched Rome reduce her mother (the woman who had the love of all of Egypt, who was called nea Isis, new Isis, who led armies and conquered kingdoms and loved, irrevocably) to the title of whore for eight years; Shimuka introduces Selene to Jainism, and she finds peace for the first time in her life.

He teaches her how to sing the old hymns, and, one day, she offers to sing some of the songs she remembers from Egypt. She tells him of the giant pyramids that were built ages ago; he shows her Jain monasteries, all pale-stone and delicate carvings. She talks about hippos, fat and lumbering and sharp-toothed, and Shimuka takes her to one of his favorite lakes to show her a peacock’s dance.

When Shimuka rages and starts to become a tyrant (note, there’s no evidence as to why he was considered a tyrant), Cleopatra Selene can guide him away from it. She’s her mother’s daughter; she knows how to manipulate. But she’s also her father’s: she loves, deeply, immediately, and knows no way to love other than with all her heart.

And now that Cleopatra Selene’s away from Octavian? She finally has the power to address the abuse she suffered under him. And if she’s smart- and she is, she’s just as brilliant and vivid and savvy as her mother ever was- then Cleopatra Selene would slowly, quietly, increase the trade benefits of other empires. Not by increasing taxes for Rome imports/exports; by lowering taxes for Chinese silks, or North Indian stones. She would foster a seething hatred of Rome via art. She would be very careful, and by the time the Guptas rise, there would be a lasting imprint of anti-Roman sentiment in South India.

It takes them both some time, this deposed Egyptian princess and this ambitious Indian warrior-king. It takes them some disagreements, some fears, some compromises- but Cleopatra Selene knows strategy and Shimuka is shrewd, and they meet, somehow, somewhere, in the middle.

It’s a love story in the making.

Notes:

*Satavahana: sata means hundred; vahana is properly translated as “that which carries,” and refers to pretty much any mount. There are other translations to this, but I’m going by the direct roots.

**There are other ideas of how Caesarion died, but in this text we’re going by Plutarch’s Selected Lives.

***Dates for Shimuka are even more controversial than dates for Cleopatra Selene. I have chosen to go with a version in which he lives during her lifetime, not three centuries before. However, I do acknowledge that there are schools of thought that disagree.

#history#Cleopatra Selene II#egyptian history#Shimuka#indian history#satavahana dynasty#this is very very very interesting to me#and honestly if i only convert one person to this ship i will be ecstatic#because i've been alone in this for nine years alright#nine years is a LONG time#but yeah if y'all have more questions about this LET ME KNOW#I LIKE THIS SHIT#my writing#the-sober-folly

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

ALRIGHT okay I will attempt to explain this to the best of my ability, which is currently being held together by tape and coffee

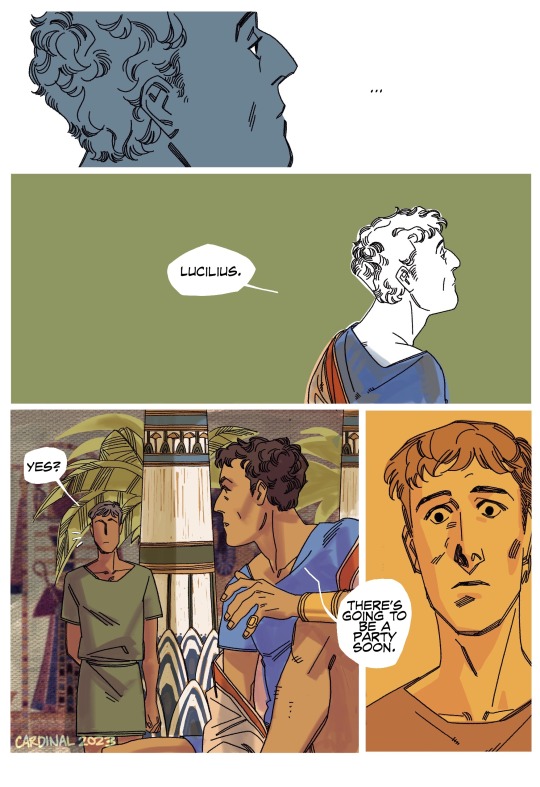

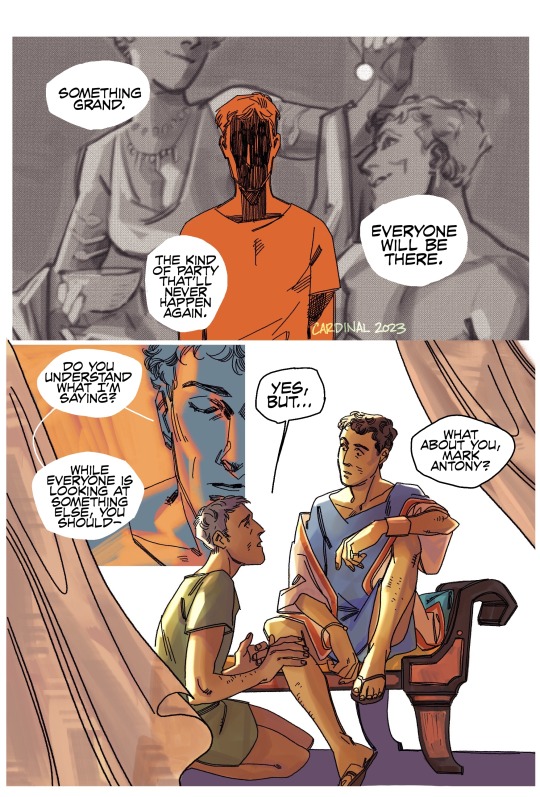

so I have a long running post philippi story focusing on the octavian-antony divorce arc conflict and it's heavily dramatized and full of dead people. it's one part historical, one part my own invention, and one part fucking around with ideas (or the lack there of) in movies about antony and cleopatra. many of which are bad! however. there is a bad one that's actually good. like, I wouldn't recommend it except that I talk about it constantly.

it's the 1953 movie, Serpent of the Nile and I have not known peace since watching it. it's one of the more interesting takes on antony and cleopatra (TO ME), and more importantly: I'm obsessed with the plot point where antony helps lucilius escape egypt to warn octavian.

this scene is partially inspired by that! this scene is partially inspired by several things, but that's the one to mention bc I haven't published any of this story except for the periodic scene I've drawn for fun so listing the rest of it will not add to this experience and also I’m very sleepy right now

the egyptian wall backgrounds in the first page and the last page are of a tomb wall painting, the third page uses an illustration of the death of antony for shakespeare's antony and cleopatra, and on the second page is actually my own painting of antony and cleopatra after giambattista pittoni's painting of antony, cleopatra, and the famous pearl incident

additionally, that last page. the floor. that's a relief commemorating the battle of actium. I'd been reading about depictions of actium and it is. intriguing, especially since my first thought wrt to all of that is usually abt the bodies in the water and how they'll never be buried or antony's parthian fuck up setting the stage for all of this.

also this specifically. fascinating.

Representations and Re-presentations of the Battle of Actium, Barbara Kellum

#mark antony#lucilius#roman empire tag#drawing tag#komiks tag#long post#antony and octavian are divorced but also in a 'the monster you know' kind of way#octavian's reaction to antony's hello is to turn to octavia and say 'how sweet. I almost miss him. what do you think?'#sometimes a marriage is to two people but also that's on antony for not realizing the extent of which marrying octavia was also marrying#octavian. you know. like bro. that scene in the french musical where octavia is like no :( i love him :( and octavian is like#he FUCKED ME OVER BY FUCKING OVER YOU. that's what it is#god have i ever talked to you guys about french musical octavian. obsessed with him. what on earth is going on with that guy#anyway! farewell! I have been watching the live action one piece and I NEED to draw mihawk and shanks RIGHT NOW

376 notes

·

View notes