#uaepavilion

Photo

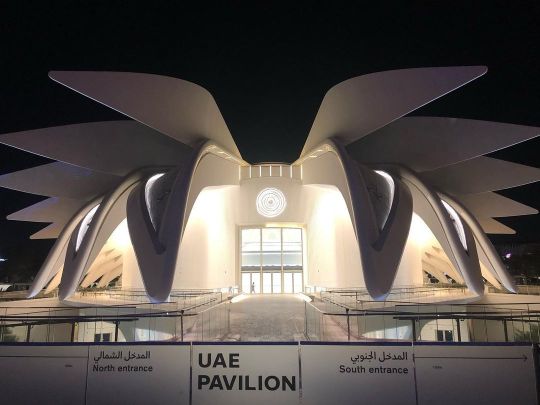

The land of dreamers. @uaepavilion @uaepavilion.ae @uaeatexpo ::::::::::::::::::::: Another Architecture marvel from the @expo2020dubai ... A three-story structure totaling 15,064 sqm. Its design features 28 moveable wings, where you meet the dreamers who are creating a better future for all. Unfortunately i wasn't carry the tripod. But managed to capture handheld with 1/10s :::::::::::::::::::::::: #uaepavilion #dubai #ExpoMoments @expo2020dubai #canonme @canonme #uaepavillion #celebration #people #mydubai @mydubai #fotouae @foto.uae #visitdubai #dubailife #ourfotoworld #photowalkglobal #yourshotphotographer #natgeoabudhabi #middleeast #nightphotography #futuristic #shotonsigma #calatrava #calatravaarchitecture #santiagocalatrava :::::::::::::: Sigma fp & 20mm Art. f/1.4, 1/10sec. Gear from @aabworld @sigma.aab :::::::::: @dubaiculture @dubai_calendar @placestovisitindubai @visit.dubai @calatravaofficial @santi_calatrava (at Dubai, United Arab Emiratesدبي) https://www.instagram.com/p/CdC5I-LvSJY/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#uaepavilion#dubai#expomoments#canonme#uaepavillion#celebration#people#mydubai#fotouae#visitdubai#dubailife#ourfotoworld#photowalkglobal#yourshotphotographer#natgeoabudhabi#middleeast#nightphotography#futuristic#shotonsigma#calatrava#calatravaarchitecture#santiagocalatrava

0 notes

Photo

The Last Photo of @expo2020dubai at @uaeatexpo UAE Pavilion 🇦🇪 ♥️ Thank you for the memories 🙌🏼 #uaepavilion #expo #expo2020 #expo2020dubai #finale #dubai #uae (at Expo 2020 Dubai) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cb2VnvOvfNj/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

#expo2020 #05march2022 #uaepavilion (at Expo 2020 Dubai) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ca49KLOsHKP/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

Trust your wings #NowOrNeverExpo . . . . . . . . . . . . . #expo2020 #expo2020dubai #expodubai2020 #dubai #dubailife #lovindubai #dxb #uae #uaepavilion (at Expo 2020 Dubai) https://www.instagram.com/p/CaZqWz_MG6J/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

One of the must visit pavilions in the #Expo2020 site is the #UAEPavilion. If you haven’t visited it, then you must go there ASAP! 😁 Just ensure to book your #SmartQueue through the Expo app. 🇦🇪🇦🇪🇦🇪 #jazperjay #jazperjayphotography #dubaiexpo2020 #expo2020dubai #Dubai #unitedarabemirates #davaophotographer #dubaiphotographer #davaobloggers #expomoments #expoinfocus (at Expo 2020 Dubai) https://www.instagram.com/p/CaNjTh3BN4R/?utm_medium=tumblr

#expo2020#uaepavilion#smartqueue#jazperjay#jazperjayphotography#dubaiexpo2020#expo2020dubai#dubai#unitedarabemirates#davaophotographer#dubaiphotographer#davaobloggers#expomoments#expoinfocus

0 notes

Photo

It’s my future house😀✨ I’m going to UAE pavilion next time🍀 なんなんだろなこの引きつけるデザインは、横から見てもかっこいいんだよなぁ。 4回中4回知り合いと言ってるから今度は1人で、自分の意思で自由に動こう、むしろ1人でいるべきだは #dubai #uae #mydubai #visitdubai #dubailife #Japan #fromjapan #shizuoka #dxb #dubaiexpo #海外移住 #ドバイ #静岡 #DubaiDestinations #dubaiexpo2020 #expo2020 #uaepavilion (Expo 2020 Dubai) https://www.instagram.com/p/CZuh68FPanF/?utm_medium=tumblr

#dubai#uae#mydubai#visitdubai#dubailife#japan#fromjapan#shizuoka#dxb#dubaiexpo#海外移住#ドバイ#静岡#dubaidestinations#dubaiexpo2020#expo2020#uaepavilion

0 notes

Photo

The Land of Dreamers Who Do . #dubaiexpo #dubaiexpo2020 #dubaiexpo2020uae #expo2020 #expo #expo2020dubai #dubai #dxb #mydubai #uae #uaepavilion #unitedarabemirates #unitedarabemiratespavilion https://www.instagram.com/p/CVccO2ihYtJ/?utm_medium=tumblr

#dubaiexpo#dubaiexpo2020#dubaiexpo2020uae#expo2020#expo#expo2020dubai#dubai#dxb#mydubai#uae#uaepavilion#unitedarabemirates#unitedarabemiratespavilion

1 note

·

View note

Text

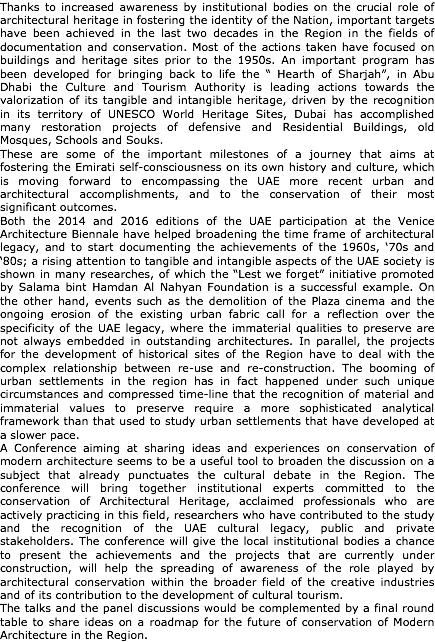

CONSERVATION AND REUSE OF MODERN ARCHITECTURE: EXPERIENCES AND PERSPECTIVES

#dubaidesignweek#uaemoderm#docomomo#adaptivereuse#conservation#heritage#modernarchitecture#vernacular#johnharris#johnelliot#halcrow#high-rise#building typology#master planning#lest we forget#uaepavilion

0 notes

Photo

When a bus stop becomes art. Degenerative Disarrangement, Vikram Divecha #uaepavilion Curated by Hammad Nasar #venicebiennale2017 #venice

0 notes

Photo

the amazing pavilion of United Arab Emirates #uaepavilion #expo #expo2020 #expo2020dubai #dubai #uae 🇦🇪 (at Expo 2020 Dubai) https://www.instagram.com/p/CViApgGv4qt/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

The Arabs in Venice

Are Arabs inherently incapable of producing anything of architectural value aside from the historic, the exotic and the peculiar? Are they unable to make any substantive theoretical contributions aside from the 14th century urban musings of Ibn Khaldoun? Are the ashwaiy’yat of Cairo and its medieval core the only sites worthy of the attention of would-be scholars and experts? Are we forever condemned between the trappings of heritage conservation, including the constant, incessant, and unrelenting feteshization of 20th century modernism in its various local variants, and the noble efforts of NGO’s alleviating human suffering in slums? These were just some of the questions that sprung to mind as I was traversing the hollow grounds of the Venice Architecture Biennale. Understandable given the scarce Arab representation (only four countries, and one symbolic participation) but also because of the general debate accompanying this event. As usual the discussions centered on western pavilions with the occasional exotic sidekick. The Arab pavilions were – for the most part – left out among the architectural elite and experts. There were exceptions of course, and some did receive positive and critical feedback – but still there was this nagging feeling that things haven’t really changed that much.

Figure 1: The UAE National Pavilion poster on a wall adjacent to the Gallerie dell’Academia, Venice.

Indeed walking through the Giardini (the main venue of the event) with its majestic pavilions all lined up on the main pathway one is reminded of the old colonial order – with newly instated countries punctuating the line-up. But here they are: Britain, US, France, Belgium, Netherlands, Spain – the architectural masters surrounded by their lesser brethren’s. The Arsenale (the other Biennale venue) is a bit more egalitarian, given the specific linear layout of the former shipyard. So how did the “Arabs” fit in this cacophony? Among the four participants only Egypt has permanent status and its own pavilion structure. Newcomers (relatively speaking, they have been participating for several years in both the art and architecture versions) are Bahrain, Kuwait and the UAE. Yemen is included for the first time this year although its presence can be considered largely symbolical – albeit a very significant one.

A necessary distinction needs to be drawn between Egypt and its Gulf counterparts. Egypt with a long and distinguished architectural history, as well as educational institutions churning out thousands of architects every year is quite different from its Gulf counterparts. Considered quite young as far as nations go their architectural culture is yet to mature to be able to compete in any significant way with its more established neighbors. Yet this also lends itself to cliché building. For many their architectural output is the result of money-hungry Western (as well as other Arab) consultants capitalizing on the desire for spectacular and speedy developments; as such the resultant built environment is one that is transient, speculative and not worthy of any serious architectural discourse. Their participation in architectural events is either heritage oriented, or a form of political propaganda, all placed within lavish and glossy installations (“well presented display” is a common refrain). In general – the argument goes – they do not offer anything beyond surface architecture that does not lend itself to any sort of relevant theorization. Recognizing these criticisms some Gulf countries go beyond the boundaries of the nation state – somehow implying that the local architectural output is insufficient – and develop themes and subjects that deal with pan-Arabism for example (see Bahrain’s curious installation from 2014, curated by two Lebanon based architects).

This year was a bit different for a change. Indeed all four participating countries had something interesting to say and offered ideas and concepts that are not necessarily tied to their limiting local context but are also useful in terms of broader architectural theory. If we take into account the theme “Reporting from the front” this acquires further poignancy. Take Egypt for example – where the notion of architectural and urban battlefields is a perfect match for its urban conditions. The country is filled with stories of residents challenging the status quo and finding ingenious solution to their lives. The pavilion is commissioned (curated) by Ahmed Hilal, an Egyptian graduate student of architecture at Politechnico Milan, and a team of Italian and Egyptian architects.[i] They set out to map informal practices in Cairo and other cities, as well as presenting “surgical interventions.” The presentation is titled “Reframing back: imperative confrontations.” Conceived as a kind of story telling they have collaborated with numerous researchers and practices who are at the forefront of these efforts. Projects were selected from Western institutions such as PennDesign and the ETH, in addition to some local Egyptian universities as well including MSA. This international collaboration demonstrates the intense interest in Cairo’s built environment and the challenges it faces. There were also contributions from local practices. The effort is well-researched and presented professionally marking a qualitative shift from the last two events. While some have criticized the overwhelming nature of the information presented – there are really a lot of stories to tell – it does in many ways echo the urban chaos of cities such as Cairo. The suitability though for an event such as the Biennale where a message needs to be clearly communicated is questionable. Clearly the presentation would have benefited from some paring down and a clearer focus on the main theme. Also as Manar Moursy, one of the energetic contributors to the project, pointed out “left out of the exhibition is the work of non-architects” which would have greatly enriched the subject (and resulted in even more stories).[ii] But there is no doubt that the Egyptian pavilion presented a solid case that enriched the architectural dialogue, and the various topics that were on offer in Venice.

Figure 2: Inside the Egyptian pavilion.

Kuwait in its installation amidst the ancient spaces of the Arsenale moved beyond the confines of political boundaries and looked at the body of water separating the region from Iran – the “Gulf” – as a site full of urban and architectural potential. As the curators Ali Karimi (from Bahrain) and Hamad Bukhamseen (Kuwait) point out they are challenging the status quo by exploring “how the architect can imagine a scale beyond the national.”[iii] Given the political context of the region such a proposition is inherently fraught with difficulties. Even the naming here is problematic – the generic word “Gulf” is used (although as the curators told me it is also meant as a metaphor, indicating separation). This particular body of water is situated within a larger socio-political context and the focus is on its numerous islands. In viewing these as a potential site for exploring identity, culture and urban development parallels are drawn to the developments taking place in the region – including the various artificial islands under construction. As they observe, islands are the only space left for experimentation. The exhibition itself is conceived as a research project, documenting and mapping the numerous islands in the Gulf; additionally proposals have been sought from architectural firms to provide “instances” or architectural interventions that seek to address notions of unity, separation, and ecology to name a few. Seven proposal are included – most are practices within the Gulf with only two founded by Kuwaiti architects; the rest are either firms with an Arab partner/founder or are located throughout the region and the US.

While conceptually strong, and the accompanying research and proposals are outstanding in terms of content as well as creative output, the actual installation is quite minimal. The space, occupying a large, uninterrupted area in the Arsenale, is conceived as a large body of water. To that effect bluish, shiny metallic tiles have been placed on the ground, punctuated by white massing models (proposals for the island design). The overall effect is impressive – particularly early in the day before the shiny ground is covered in dust and sand brought in by visitors and passersby (the space acts as a conduit to subsequent pavilions). Yet there is a feeling that the richness of the material and proposals has not been effectively communicated. In contrast to the Egyptian pavilion where one is inundated with information, here the effect is minimal with a sense that information is incomplete. Yet aside from these exhibition design issues perhaps the most positive is the engagement with local architectural talent. Much more needs to be done in that regard, but the beginnings are here. A true progressive local architectural culture can only emerge when the architects of the region are effectively engaged in shaping their built environment.

Figure 3a: The shiny surface of the Kuwaiti pavilion. Visitors appear as if they are walking on water.

Figure 3b: Detailed view of a model and accompanying graphics

Immediately following Kuwait is the Bahraini space which contains a sculptural installation made from aluminum interspersed with photographs and an LCD screen displaying a movie about the production of said material. Aluminum is in fact the theme Bahrain has chosen for its participation in the Biennale. At first glance it seems a curious and puzzling choice. What possibly is the connection to this small island nation? As it turns out Bahrain has the fourth largest refining factory in the world. Yet their choice goes beyond industrial concerns to address larger issues pertaining to identity, vernacular architecture and appropriation.

While the display does not directly or clearly address these issues they are explained in the accompanying publication. It starts out with a “conformation.” A brief, slightly meandering, statement about the film and photographs (in the exhibition), including a discussion about the relationship between the machine and human body in various moments of production. Things are further clarified in the commissioners statement which mentions Bahrain’s engagement with modernity and that aluminum is one particular manifestation of this. The Venice contribution is construed as a “new reading” of this material and its various applications. Ali Karimi (co-curator of the Kuwait pavilion) further elaborates on the notion of the local vernacular, and correctly points out that when it comes to the Gulf, such constructs are “wishful fiction.” By looking at the various architetures produced, including the use of material, we see that Bahrain has engaged in a process of appropriation and that “aluminum is the new Bahraini vernacular, another step in the history of self definition through reappropriation.” These are fascinating ideas, moving the discourse concerning urbanization and architecture in the Gulf beyond the typical fixations (too many to mention). Particular their engagement with modernity and its adaptation within a local context is poignant. Yet it is unfortunate that the accompanying display somehow misses all of that. The pavilion is curated by Anne Holtrop (a Dutch architect) and Noura Al Sayeh (a Bahraini architect and longtime advocate of cultural and heritage preservation). As noted the large space is occupied by a rather small structure made of aluminum. Its shape consists of a series of arches that define certain spaces within which people can move. A series of framed photographs are placed rather awkwardly alongside the structure. Altogether a disorienting display whose meaning is not entirely clear.

The accompanying book explains the research that was done – none of which found its way in the installation. This includes an archival search in newspaper records, advertisements as well as a substantive mapping project to show the diffusion of the material in the urban and architectural landscape of Bahrain. Of note here are photographs by Camille Zakaria which focus on the application of aluminum in various facades. These offer a fascinating glimpse into the variation that has resulted from its use, and also how it has become very much part of the local vernacular This also makes an interesting connection to other urban centers in the region. The need for being minimal is understood but perhaps things got too far this time. Nevertheless it is a fascinating and courageous idea, that is deserving of further discussion. It shows that we can in the Gulf move beyond the confines of heritage, history and identity and have the ability and resources to make a substantive contribution to the architectural discourse concerning regionalism in architecture.

Figure 4: The Bahrain installation. An arched structure made of Aluminium.

The pavilion of the UAE – which I curated – adopts a similar approach in the sense that it is an attempt to go beyond clichés and sterotypes in the region. The theme is titled: “Transformations: The Emirati National House.” It seeks to directly engage with the theme of the Biennale by examining architectures that enhance the quality of life. To that effect I have looked at one particular housing typology which began in the early 1970s and the extent to which it was transformed by its inhabitants. Aside from offering insight into a significant parts of the UAE’s urban and architectural landscape, it also suggest lessons of wider significance. It is an example, and a success story, of a socially conscious architecture that is not speculative or iconic. Indeed provision of decent housing for the disadvantaged is a universal concern and the Sha’abi house demonstrates how to construct an adaptable and flexible typology. The continuous use and change of this model is a rare example of an ongoing architectural experiment. Within the context of the Gulf and the UAE highlighting such cases moves the architectural discourse away from one focused on spectacular and iconic architecture to the spaces of the everyday. It shows the diversity of its built environment and the ingenuity of its residents.

Figure 5: A visitor to the UAE pavilion inspects a survey display of the National House [Photography: Mohamed Somji]

Indeed the Sha’abi house could be construed as a form of vernacular architecture that challenges notion of top-down planning so prevalent in the region. Such views were expressed in the 1960s in the west as a reaction to modernist planning ideas. Starting with Rudofsky’s exhibition about “architecture without architects.”[iv] Amos Rapoport in his landmark “House, Form and Culture” further elaborated on the significance of culture and lifestyle in determining the form of houses.[v] Paul Oliver looked at how this was applied at dwellings across the world.[vi] And in terms of planning processes and housing policy John Turner, in his aptly titled “Housing by people,” argued that “what people do themselves is more efficient, more effective, more enduring.” Similar views were expressed by Nabeel Hamdi in “Housing without houses.”[vii]

The design of the pavilion aims at moving away from traditional representational depictions. Instead the concept has been derived from the theme itself, implying a universal concern (adaptable housing) by which the pavilion seeks to position itself squarely within contemporary architectural debates. Representational issues are not completely ignored however. We would like to evoke the notion of “home” since the theme deals with domestic concerns. To achieve this we looked at the geometry of the house both from an architectural and urban perspective. The notion of transformation, which is the degree to which the house changed over time, formed an integral part in developing the concept. These transformations comprise changes that took place within a modernist plan through the accretion of elements over time. The concept of the pavilion expresses this process through the development of a strategy that seeks to spatially express these ideas. Given that the pavilion is placed within an existing historic structure, the intervention is seen as a delicate installation inserted within this solid context. Through its materiality and overall feel it should remind viewers of a home. Resultant spaces are intimate and small in scale suggesting rooms in a house

Figure 6a: Visitors in front of a structural analysis diagram of the National House [Photography: Mohamed Somji]

Figure 6b: The interactive display for the survey of the National House [Photography: Mohamed Somji]

In reviewing the Arab contribution to this year’s Biennale I hope to have unequivocally shown that contemporary Arab architecture and urbanism is not some curious sideshow, to be left to the expertise of “outsiders” who somehow know better. There is more to the Gulf than Masdar, the Palm Islands, Burj Khalifa, Louvre-AD and whatever else is usually churned out in any discussion about the Gulf city. The environment of the everyday, the spaces of our daily encounters, are where we will find a true, authentic and vibrant urbanity. And no one is more qualified to engage these matters than local actors. The region is filled with architects, researchers, writers, artists, academics, who all can make a substantive contribution to the local architectural discourse. What these pavilions also show is that there is an emerging young generation that has the necessary knowledge and drive to tackle these issues. For the Gulf this is particularly important as there is a direct need for “self-assertion” – an unwavering belief in one’s own ability, and that their architectural output – in all its various forms – matters. While outsiders are always welcome, and indeed encouraged to participate, their expertise is no substitute for knowledge that is generated locally. Only in this way will an architectural culture emerge whose voice will be heard and respected throughout the world.

Yasser Elsheshtawy. Brooklyn, NYC. July 2016.

Notes:

[i] Eslam Salem, Gabriele Secchi, Luca Borlenghi and Mostafa Salem

[ii] Moursi, M. (2016). “What happens to the knowledge produced? On Egypt at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale.” Mada Masr. June 16. http://www.madamasr.com/sections/culture/what-happens-knowledge-produced-egypt-years-venice-architecture-biennale. Also see the curator’s statement in ArchDaily: http://www.archdaily.com/790326/reframingback-imperativeconfrontations-inside-egypts-pavilion-at-the-2016-venice-biennale

[iii] Kuwait Exhibition Catalogue.

[iv] Bernard Rudofsky and Museum of Modern Art (New York N.Y.), Architecture without Architects, an Introduction to Nonpedigreed Architecture (New York,: Museum of Modern Art; distributed by Doubleday, Garden City, 1964).

[v] Amos Rapoport, House Form and Culture, Foundations of Cultural Geography Series (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.,: Prentice-Hall, 1969).

[vi] Paul Oliver, Dwellings: The Vernacular House World Wide (Phaidon London, 2003).

[vii] John F. C. Turner, Housing by People : Towards Autonomy in Building Environments, Ideas in Progress (London: Marion Boyars, 1976). Nabeel Hamdi, Housing without Houses : Participation, Flexibility, Enablement (New York, N.Y.: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991).

1 note

·

View note