#would they see themselves reflected in the professionally accomplished woman in great stable relationship with cheating on side

Note

Just wanted to add to your excellent discourse (please ignore if your sick of it) that while clearly the show (really C*rina) wanted to give us the it's All Alex's Fault narrative in S1, 1x06 screwed that up for them. I think it was just a way to justify Alex getting involved in Jesse's alien agenda, but because the showrunner wasn't big on backstory, she didn't anticipate that all Alex's actions take on a very different flavor when he's viewed, like Michael, as a traumatized, abused adult.

it sometimes takes longer to regenerate the spoons to express myself, but the topic of Alex and *waves a hand* everything really is one I still have a lot to express about, so here goes.

I think you're right on the money that CAM didn't anticipate fandom's reaction to Alex. It's clear she didn't realize what Malex would mean to queer audiences, or she wouldn't have done what she's done with s2. Full disclosure, I realize there are queer fans who fully enjoyed it. I mean that for a lot of us, Malex was a first story of it's kind - a same sex Epic Destined Soulmates Shit. And it's partly why we've glomped so hard on it and consequently were horrified at how s2 tore that aspect of the story down (especially in the stark contrast to Echo's treatment). But just as importantly, I suspect she was quite (negatively) surprised at the reception of Alex himself.

She molded a lot of the RNM characters with a definite agenda (which I approve of, whatever her motivation), racebending and queering them etc. left, right and center. The issue is, she tacked on the various characteristics and backstories (insofar as she made them) without thinking through and realizing what consequences they would actually have for the characters, as in how they would inform their actions and our perceptions of them. The particular intersection of gay, disabled vet and CA survivor with PTSD, absent Indigenous mother and shitbag homophobic abuser father didn’t have any significant meaning to her, so why should it have to the audiences? It’s pretty clear from her interviews, that the teacher’s pet was Michael (and spoiler alert, not Trevino), the sexy bad boy whom she tried to mold into Dean Winchester formula, but made him explicitly bi and for more whump gave him more storied history of child abuse and queer trauma. Alex was supposed to be a backdrop for him, a make-out partner - it’s clear she never intended to explore his story or his point of view, didn’t even have the backstory on his time in the AF (cue his totally different rank in pilot vs rest of the series) or how he lost his leg (the story we heard in 308 is so criminally under-researched there’s no way they sat on it for 3 years; never mind that CAM openly admitted to not having backstories for characters at all just because). But if she wanted the audiences not to care (that much / more than about her darlings) for Alex, you are right, she screwed up.

106 did a lot of the heavy lifting here by exposing and accidentally hinting at the horrific abuse Alex went through. As you noticed, it made audiences view Alex’s actions through a different lens. We’ve realized for example what must’ve been his thoughts and feelings in 103, when he was confronted by his abuser, the same man who permanently disfigured Michael with impunity, now giving subtle hints how Alex just being seen with him is inappropriate... you get my drift. But! what’s fascinating, is that CAM didn’t. In one of the camsplaining tweets she mentioned that Alex was simply ashamed of Michael in this scene. And honey, you may have intended it this way, but just by giving a hint of this character’s backstory you’ve given us a completely different perspective, not our fault you can’t see it yourself.

106 backstory gave us the core of Alex’s motivations, making him a fascinating character we could start to understand instead of just a tortured gay lover #2 (the one who’s sole fault it is Malex doesn’t work out). Other episodes of s1 also showed us facets of Alex that complemented and filled out that silhouette, like showing us how the grown up abuse survivor confronts his abusers (forgive but not forget for Kyle, karmic retribution and stopping the harm with Jesse), how despite/due to his shitty family situation he’s the one taking care of the emotional needs of his childhood found family of Liz, Maria and Mimi (!), etc. etc. Notice that after s1, this branching out - Alex having storylines separate from Michael that show off his character - is severely curtailed if not stopped completely: all his interactions with Maria are about Michael, the entirety of Forlex is just a foil for Malex and so on. So I have a sneaking suspicion she (really, they) did realize they made Alex too relatable, too interesting, too bloody important to people, and needed to dial it back so this character could fall back into his predestined groove of the scapegoat for everything bad in Malex and in general. Because as we know, if in doubt, it’s All Alex’s Fault, but that’s a rant for a different occasion :)

#thanks for the ask!#rnm my behated#anti rnm writer's room#anti carina#Alex Manes#also I keep thinking about my baby#Ianto Jones#and how he became the audience's favorite/viewpoint eve tho Gwen was meant for this role#and how even the queer show creators didn't anticipate#how millenials in 2006 would react#would they see themselves reflected in the professionally accomplished woman in great stable relationship with cheating on side#or the underappreciated secretary with bloody love life just figuring out he's queer?#the point is#it happens#creators not realizing how the audiences would view the characters they created#even tho it logically follows from what's on screen#but CAM and the writers room she created#lacked the ability and willingess#to adapt and change their own perception of characters#since it's so much easier to view them as two-dimensional cut outs#that can be bent into any shape the Plot requires

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

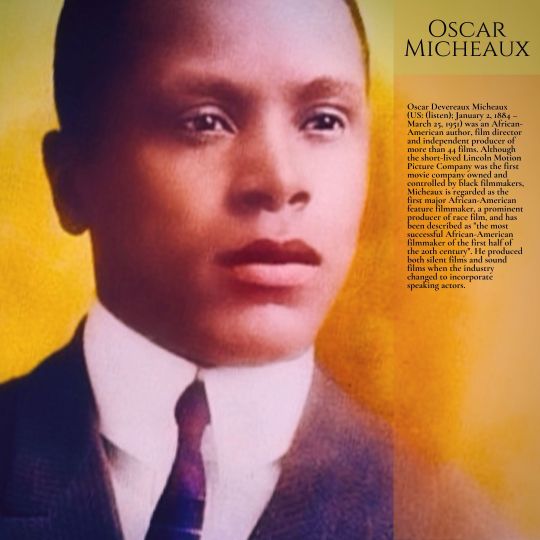

Oscar Micheaux

Oscar Devereaux Micheaux (US: (listen); January 2, 1884 – March 25, 1951) was an African-American author, film director and independent producer of more than 44 films. Although the short-lived Lincoln Motion Picture Company was the first movie company owned and controlled by black filmmakers, Micheaux is regarded as the first major African-American feature filmmaker, a prominent producer of race film, and has been described as "the most successful African-American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th century". He produced both silent films and sound films when the industry changed to incorporate speaking actors.

Early life and education

Micheaux was born on a farm in Metropolis, Illinois, on January 2, 1884. He was the fifth child born to Calvin S. and Belle Michaux, who had a total of 13 children. In his later years, Micheaux added an "e" to his last name. His father was born a slave in Kentucky. Because of his surname, his father's family appears to have been owned by French-descended settlers. French Huguenot refugees had settled in Virginia in 1700; their descendants took slaves west when they migrated into Kentucky after the American Revolutionary War.

In his later years, Micheaux wrote about the social oppression he experienced as a young boy. His parents moved to the city so that the children could receive a better education. Micheaux attended a well-established school for several years before the family eventually ran into money troubles and were forced to return to the farm. The discontented Micheaux became rebellious and his struggles caused problems within his family. His father was not happy with him and sent him away to do marketing in the city. Micheaux found pleasure in this job because he was able to speak to many new people and learned social skills that he would later reflect in his films.

When Micheaux was 17 years old, he moved to Chicago to live with his older brother, then working as a waiter. Micheaux became dissatisfied with what he viewed as his brother's way of living "the good life". He rented his own place and found work in the stockyards, which he found difficult. He moved from the stockyards to the steel mills, holding down many different jobs.

After being "swindled out of two dollars" by an employment agency, Micheaux decided to become his own boss. His first business was a shoeshine stand, which he set up at a wealthy African American barbershop, away from Chicago competition. He learned the basic strategies of business and started to save money. He became a Pullman porter on the major railroads, at that time considered prestigious employment for African Americans because it was relatively stable, well paid, and secure, and it enabled travel and interaction with new people. This job was an informal education for Micheaux. He profited financially, and also gained contacts and knowledge about the world through traveling as well as a greater understanding for business. When he left the position, he had seen much of the United States, had a couple of thousand dollars saved in his bank account, and had made a number of connections with wealthy white people who helped his future endeavors.

Micheaux moved to Gregory County, South Dakota, where he bought land and worked as a homesteader. This experience inspired his first novels and films. His neighbors on the frontier were predominately blue collar whites. "Some recall that [Micheaux] rarely sat at a table with his blue collar white neighbors." Micheaux's years as a homesteader allowed him to learn more about human relations and farming. While farming, Micheaux wrote articles and submitted them to the press. The Chicago Defender published one of his earliest articles.

Marriage and family

In South Dakota, Micheaux married Orlean McCracken. Her family proved to be complex and burdensome for Micheaux. Unhappy with their living arrangements, Orlean felt that Micheaux did not pay enough attention to her. She gave birth while he was away on business, and was reported to have emptied their bank accounts and fled. Orlean's father sold Micheaux's property and took the money from the sale. After his return, Micheaux tried unsuccessfully to get Orlean and his property back.

Writing and film career

Micheaux decided to concentrate on writing and, eventually, filmmaking, a new industry. He wrote seven novels. In 1913, 1,000 copies of his first book, The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer, were printed. He published the book anonymously, for unknown reasons. Based on his experiences as a homesteader and the failure of his first marriage, it was largely autobiographical. Although character names have been changed, the protagonist is named Oscar Devereaux. His theme was about African Americans realizing their potential and succeeding in areas where they had not felt they could. The book outlines the difference between city lifestyles of Negroes and the life he decided to lead as a lone Negro out on the far West as a pioneer. He discusses the culture of doers who want to accomplish and those who see themselves as victims of injustice and hopelessness and who do not want to try to succeed, but instead like to pretend to be successful while living the city lifestyle in poverty. He had become frustrated with getting some members of his race to populate the frontier and make something of themselves, with real work and property investment. He wrote over 100 letters to fellow Negroes in the East beckoning them to come West, but only his older brother eventually took his advice. One of Micheaux's fundamental beliefs was that hard work and enterprise would make any person rise to respect and prominence no matter his or her race.

In 1918, his novel The Homesteader, dedicated to Booker T. Washington, attracted the attention of George Johnson, the manager of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company in Los Angeles. After Johnson offered to make The Homesteader into a new feature film, negotiations and paperwork became inharmonious. Micheaux wanted to be directly involved in the adaptation of his book as a movie, but Johnson resisted and never produced the film.

Instead, Micheaux founded the Micheaux Film & Book Company of Sioux City in Chicago; its first project was the production of The Homesteader as a feature film. Micheaux had a major career as a film producer and director: He produced over 40 films, which drew audiences throughout the U.S. as well as internationally. Micheaux contacted wealthy academic connections from his earlier career as a porter, and sold stock for his company at $75 to $100 a share. Micheaux hired actors and actresses and decided to have the premiere in Chicago. The film and Micheaux received high praise from film critics. One article credited Micheaux with "a historic breakthrough, a creditable, dignified achievement". Some members of the Chicago clergy criticized the film as libelous. The Homesteader became known as Micheaux's breakout film; it helped him become widely known as a writer and a filmmaker.

In addition to writing and directing his own films, Micheaux also adapted the works of different writers for his silent pictures. Many of his films were open, blunt and thought-provoking regarding certain racial issues of that time. He once commented: "It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights." Financial hardships during the Great Depression eventually made it impossible for Micheaux to keep producing films, and he returned to writing.

Films

Micheaux's first novel The Conquest was adapted to film and re-titled The Homesteader. This film, which met with critical and commercial success, was released in 1919. It revolves around a man named Jean Baptiste, called the Homesteader, who falls in love with many white women but resists marrying one out of his loyalty to his race. Baptiste sacrifices love to be a key symbol for his fellow African Americans. He looks for love among his own people and marries an African-American woman. Relations between them deteriorate. Eventually, Baptiste is not allowed to see his wife. She kills her father for keeping them apart and commits suicide. Baptiste is accused of the crime, but is ultimately cleared. An old love helps him through his troubles. After he learns that she is a mulatto and thus part African, they marry. This film deals extensively with race relationships.

Micheaux's second silent film was Within Our Gates, produced in 1920. Although sometimes considered his response to the film Birth of a Nation, Micheaux said that he created it independently as a response to the widespread social instability following World War I. Within Our Gates revolved around the main character, Sylvia Landry, a mixed-race school teacher. In a flashback, Sylvia is shown growing up as the adopted daughter of a sharecropper. When her father confronts their white landlord over money, a fight ensues. The landlord is shot by another white man, but Sylvia's adoptive father is accused and lynched with her adoptive mother.

Sylvia is almost raped by the landowner's brother but discovers that he is her biological father. Micheaux always depicts African Americans as being serious and reaching for higher education. Before the flashback scene, we see that Sylvia travels to Boston, seeking funding for her school, which serves black children. They are underserved by the segregated society. On her journey, she is hit by the car of a rich white woman. Learning about Landry's cause, the woman decides to give her school $50,000.

In the film, Micheaux depicts educated and professional people in black society as light-skinned, representing the elite status of some of the mixed-race people who comprised the majority of African Americans free before the Civil War. Poor people are represented as dark-skinned and with more undiluted African ancestry. Mixed-race people also feature as some of the villains. The film is set within the Jim Crow era. It contrasted the experiences for African Americans who stayed in rural areas and others who had migrated to cities and become urbanized. Micheaux explored the suffering of African Americans in the present day, without explaining how the situation arose in history. Some feared that this film would cause even more unrest within society, and others believed it would open the public's eyes to the unjust treatment of blacks by whites. Protests against the film continued until the day it was released. Because of its controversial status, the film was banned from some theaters.

Micheaux adapted two works by Charles W. Chesnutt, which he released under their original titles: The Conjure Woman (1926) and The House Behind the Cedars (1927). The latter, which dealt with issues of mixed race and passing, created so much controversy when reviewed by the Film Board of Virginia that he was forced to make cuts to have it shown. He remade this story as a sound film in 1932, releasing it with the title Veiled Aristocrats. The silent version of the film is believed to have been lost.

Themes

Micheaux's films were made during a time of great change in the African-American community. His films featured contemporary black life. He dealt with racial relationships between blacks and whites, and the challenges for blacks when trying to achieve success in the larger society. His films were used to oppose and discuss the racial injustice that African Americans received. Topics such as lynching, job discrimination, rape, mob violence, and economic exploitation were depicted in his films. These films also reflect his ideologies and autobiographical experiences.

Micheaux sought to create films that would counter white portrayals of African Americans, which tended to emphasize inferior stereotypes. He created complex characters of different classes. His films questioned the value system of both African-American and white communities as well as caused problems with the press and state censors.

Style

Critic Barbara Lupack described Micheaux as pursuing moderation with his films and creating a "middle-class cinema". His works were designed to appeal to both middle- and lower-class audiences.

Micheaux said,

My results ... might have been narrow at times, due perhaps to certain limited situations, which I endeavored to portray, but in those limited situations, the truth was the predominate characteristic. It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights. I am too imbued with the spirit of Booker T. Washington to engraft false virtues upon ourselves, to make ourselves that which we are not.

Death

Micheaux died on March 25, 1951, in Charlotte, North Carolina, of heart failure. He is buried in Great Bend Cemetery in Great Bend, Kansas, the home of his youth. His gravestone reads: "A man ahead of his time".

Legacy and honors

The Oscar Micheaux Society at Duke University continues to honor his work and educate about his legacy.

1987, Micheaux was recognized with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

1989 the Directors Guild of America honored Micheaux with a Golden Jubilee Special Award.

The Producers Guild of America created an annual award in his name.

In 1989, the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame gave him a posthumous award.

Gregory, South Dakota holds an annual Oscar Micheaux Film Festival.

In 2001 Oscar Micheaux Golden Anniversary Festival (March 24–25) Great Bend, Kansas

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Oscar Micheaux on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

On June 22, 2010, the US Postal Service issued a 44-cent, Oscar Micheaux commemorative stamp.

In 2011, the Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, Virginia created a category for donors, the Micheaux Society, in honor of Micheaux.

Midnight Ramble: Oscar Micheaux and the Story of Race Movies (1994) is a documentary whose title refers to the early 20th-century practice of some segregated cinemas of screening films for African-American audiences only at matinees and midnight. The documentary was produced by Pamela Thomas, directed by Pearl Bowser and Bestor Cram, and written by Clyde Taylor. It was first aired on the PBS show The American Experience in 1994, and released in 2004.

In 2019, Micheaux's film Body and Soul was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

The Oscar Micheaux Award for excellence was established.

The Czar of Black Hollywood

In 2014, Block Starz Music Television released The Czar of Black Hollywood, a documentary film chronicling the early life and career of Oscar Micheaux using Library of Congress archived footage, photos, illustrations and vintage music. The film was announced by American radio host Tom Joyner on his nationally syndicated program, The Tom Joyner Morning Show, as part of a "Little Known Black History Fact" on Micheaux. In an interview with The Washington Times, filmmaker Bayer Mack said he read the 2007 biography Oscar Micheaux: The Great and Only by Patrick McGilligan and was inspired to produce The Czar of Black Hollywood because Micheaux's life mirrored his own. Mack told The Huffington Post he was shocked that, in spite of Micheaux's historical significance, there was "virtually nothing out there about [his] life". The film's executive producer, Frances Presley Rice, told the Sun Sentinel that Micheaux was the first "indie movie producer." In 2018, Mack was interviewed by the news site Mic for its "Black Monuments Project", which named Oscar Micheaux as one of its 50 African-Americans deserving of a statue. He said Micheaux embodied "the best of what we all are as Americans" and that the filmmaker was "an inspiration."

2 notes

·

View notes