Text

Leroy-Carne Loop and Ice Lakes, Entiat Mountains

October 4-7, 2017

Seven-Fingered Jack (9100′)

North Spectacle Butte (8080′)

South Spectacle Butte attempt

For our annual Golden Larch Trip this year, Doug, Fay, Lisa, Steve, Deb, Brian, and Eileen joined me on the very popular Leroy-Carne Loop in the Entiat Mountains. We included a side trip to beautiful Ice Lakes and managed to tuck in some nice peaks along the way. The larch trees were close to being at their peak of golden color, and the weather started out pleasantly autumnal. But all of that was overshadowed by the incredible blizzard most of us experienced while camped at Upper Ice Lake on Friday night. It was a storm of near-biblical proportions that none of us survivors will ever forget.

DAY 1: We drove up the Chiwawa River Road to the Phelps Creek Trailhead on Wednesday morning. There were numerous cars in the parking lot, and we immediately bumped into our friends Dave and Milda, who were headed into Ice Lakes via Carne Mountain. Our group was headed to the same place, but we were entering from the north via Leroy Basin. We donned backpacks and hiked the 6 miles into the basin under sunny skies, arriving in mid-afternoon (4.2 hours from TH). There was time to do some exploration of the basin and check out the larch color. It appeared that we were about a week early for prime color; some trees were bright gold, whereas others were only green-gold.

From our camp in Leroy Basin, we could gaze directly up at the summit crags of Seven-Fingered Jack our objective for tomorrow morning.

DAY 2: We awoke at 5:30am and were on the move with summit packs just after sunrise. Our plan was to climb the northwest ridge of Seven-Fingered Jack, so we headed north to the 7700-foot col separating Leroy Creek and Big Creek. Views of Buck Mountain and other peaks to the west were excellent in the clear October air.

We soon reached the Big-Leroy Col (1.5 hours from camp), which marks the bottom of the northwest ridge. Steve and I had previously climbed this route in past decades but somehow managed to forget that it starts at a steep face of rotten volcanic breccia or tuff. Whatever the rock type, it was enough to make Lisa, Deb, Doug, Steve, and Eileen retreat back to the more-standard west slope route. Meanwhile, Fay and Brian and I decided to take our chances with the steep face. It began with an exposed Class 3 ledge system but soon eased off to Class 2-3 scrambling with only moderate exposure.

The upper part of the west ridge served up some very interesting Class 3 scrambling around numerous horns and pinnacles, but Brian decided to turn around near the midpoint. Eventually, Fay and I rejoined our west slope comrades and continued upward together.

We topped out in late morning (4.6 hours from camp) and enjoyed the calm summit for nearly an hour. Eileen had carried up Ed Miller’s memorial traveling register to leave for future parties.

Views included the incredible north face of Mt. Maude to the south...

... Stuart Range farther to the south ...

... and Entiat Meadows directly below.

We headed back down to Leroy Basin by way of the expansive southwest slope.

Once back at camp, we packed up and headed south on the Carne Mountain High Route, following the old sheepherder’s trail up to 6900-foot Leroy Pass.

The pass offered us one last look back at Seven-Fingered Jack and Leroy Basin before we turned east and left the trail.

Faint footpaths led up heather, talus, and scree to 7600-foot Ice Lakes Pass. Late-afternoon shadows were stretching across Upper Ice Lake just as we arrived at the pass. We hurried down to the lake and set up camp on some conveniently flat but very exposed pumice terraces (2.9 hours from Leroy Basin).

DAY 3: After a comfortable night of being lightly buffeted by mountain breezes, we awoke to a gorgeous sunrise over Spectacle Buttes. Or should I call them “Spectacular Buttes”?

Upper Ice Lake is strikingly beautiful in an austere, lunar-esque fashion. I think that if the moon had lakes and larch trees, it would look very similar to this.

Pink clouds streaked across the western sky ...

... and alpenglow lit up Mt. Maude.

During breakfast, Steve, Deb, and Brian announced that they would break camp and head out today, adding a climb of Mt. Maude along the way. Lisa, Doug, Fay, Eileen, and I, on the other hand, decided to make a day trip over to Spectacle Buttes. We began with a traverse around the shore of Upper Ice Lake.

We then dropped down to Lower Ice Lake, which has a user-friendly shoreline and an inviting larch-studded island.

At the lower lake, Lisa and Doug veered off to climb North Spectacle Butte, whereas Fay, Eileen, and I proceeded in the direction of South Spectacle Butte. This involved a short descent into the Ice Creek valley, then a traverse below the north butte. We crossed over the top of a huge erosion gully along the way.

An ascent through a high larch basin ended at 7300-foot Spectacle Col, between the two buttes.

Beckey’s original Cascade Alpine Guide indicates that South Spectacle Butte can be readily climbed from this col, so we were game to give it a whirl. The first 600 feet was straightforward and enjoyable, but we soon encountered an impassable notch at 7900 feet. After several attempts to get beyond the notch, we reluctantly decided to retreat and traverse over to North Spectacle Butte.

We contoured around the eastern side of the north butte, then scrambled up the northeast ridge, arriving on the summit in late afternoon (7.0 hours from camp).

The skies had been growing dark and ominous throughout the afternoon, and a light snow started to fall just as we left the summit.

We raced down the peak’s west ridge, dropped into Lower Ice Lake, then hiked back up to our camp at Upper Ice Lake. Gusty winds spit graupel pellets in our faces as we made the final traverse to camp (1.7 hours from summit). Doug and Lisa had arrived an hour before us, having tucked in North Spectacle Butte earlier in the day.

NIGHT 3: After eating a hasty dinner in the brewing storm, we all retreated to our respective tents around 7:00pm. The winds continued to grow in intensity throughout the evening, and the snowfall increased. Before long, it became a full-blown blizzard. Somewhere around 10:00pm, I got out to re-stake our wind-battered tent with rock anchors, and then I stumbled off to check on the others. Doug’s single-wall Megamid tent had suffered a blow-out at the apex and collapsed on top of him; he had no choice but to lie under it like a tarp. Fay’s lightweight double-wall tent was still standing, but it deformed badly under the wind loading and was filling with spindrift; she and Lisa were doing their best to hold it up from within.

I scurried back to our tent and jumped inside. For the next 2 hours, the winds became even more ferocious. To make things worse, the gusts continually changed direction; one gust would roar in from the west, circle around Ice Lake, then roar back in from the east. We later estimated that they reached speeds in the range of 60 to 80 mph at their peak. I spent most of that time with my feet pushed up against the corners of the tent ceiling, trying to keep it from folding over under the tremendous load. Eileen got out at midnight to replace anchor rocks that had been moved and stakes that had pulled out. Around 1:00am, the gusts abated slightly, and we both dozed off. This rest was short-lived, however, because we were awoken at 2:00am when our tent partially collapsed due to a broken pole. With no means to repair a tent pole during a blizzard, our only option was to huddle inside and accept the incoming spindrift. It was a long night.

DAY 4: At 5:20am, I announced to Eileen that it was time to move. I emptied the spindrift out of my boots and got dressed in my full battle armor, then crawled out the rally the others. Doug was more than happy to get out from under his flattened pyramid. Likewise, Fay and Lisa were very ready to escape their snow-filled cocoon. We all packed up in the still-howling wind, being careful to keep a grasp on each item lest it be whipped off to the Entiat Valley. As we ate breakfast behind a windbreak, the eastern sky gradually lightened and began to splash dawn colors across the frozen landscape. It was a visually stunning aftermath to a wild night.

We trudged up to Ice Lakes Pass and took a short break to soak in one last view of Upper Ice Lake to the east.

To the west, dark storm clouds battled with patches of deep-blue sky.

We spent the rest of our day hiking through a snowy wonderland along the Carne-Leroy High Route and down to the trailhead.

Around midday, we encountered Dave and Milda, who had also been camped at Upper Ice Lake the night before. We shared survivor tales with them, and laughed at the helplessness of our respective situations. For all of us, we felt that we’d lived through MOAB: the Mother Of All Blizzards! Fay later summed it up perfectly by saying, “We had a once in a lifetime experience; one not to missed but one not to ever be repeated.” Amen.

Approximate Total Stats: 28 miles traveled; 13,700 feet gained & lost; 3 tents damaged.

#ice lakes#seven-fingered jack#7fj#spectacle buttes#carne basin#Leroy basin#entiat mountains#Cascade Mountains#golden larch

0 notes

Text

Sitting Bull Mountain and Plummer Mountain

September 15-18, 2017

Sitting Bull Mountain (7789′)

Plummer Mountain (7870′)

In mid-September, I checked off a long-overdue item on my mountain "bucket list" by backpacking into Image Lake. Somehow this famous destination had escaped me for many years, even when it seemed that anyone and everyone who owned a pair of hiking boots had been there at least once. As an illustration of Image Lake's widespread renown, consider this tidbit: One of the books in my personal library is a coffee-table pictorial from Great Britain that honors the many, many mountain ranges around the world, and although only three of the 250-plus pages are devoted to our local Cascade Range, the cover is a full-width glossy photo of Glacier Peak rising above Image Lake. Talk about international stature! My golden opportunity recently presented itself when Eileen and Fay planned a five-day climbing trip to the Bannock Lakes area, entering via Suiattle Pass and exiting via Image Lake. It was decided that Fay would hike out on Day 5 of their trip, while I hiked in to meet Eileen with resupplies for an additional four days. Our tag-team plan actually worked, and we all had a wonderful time.

Day 1: I started at the Suiattle Trailhead on a mild, clear, Friday morning. Since this first day would involve quite a few miles on well-maintained trail, I opted to wear a semi-ancient pair of white leather Nike sneakers and to carry mountain boots on my pack. Such a strategy is often used by some climbers, but it was a new one for me. As things turned out, the sneakers were very comfortable and had a nostalgic “throw-back uniform” appearance, which probably amused some of the other trail hikers. Unfortunately, at their advanced age, the sneakers were not up to the task of backpacking; both soles came unglued somewhere around Mile 10.

The Suiattle Trail is in excellent condition most of the way, and I was able to make rapid progress. A highlight of the trail is a suspension bridge over Canyon Creek around Mile 7. This modern -yet-rustic structure is a masterpiece of backcountry bridge design and construction.

In mid-afternoon, I encountered Fay hiking down the trail from Image Lake. I gave her a solo tent to use for her last night down the trail, and she gave me some information about Eileen’s whereabouts. Farther up the trail, the forest finally opened up and yielded scenic views across the grand Suiattle River valley

Shortly after 5:00pm, I arrived at Image Lake (7.4 hours from TH). The late-afternoon sun laid long shadows across the emerald water and surrounding hillslopes. I found Eileen relaxing on the opposite shore.

Eileen had a camp set up on the other (north) side of Miners Pass, so I got to see more of the lake basin as we hiked up to the pass. The vast, sweeping, verdant hillslopes of heather and delicate parsley-like vegetation were strikingly gorgeous, especially with their backdrop of rugged mountains.

And, of course, Glacier Peak towered regally above all of the other mountains.

As we crossed over Miners Pass and descended to our camp in the meadow closely below, the northern view presented itself. This included Stonehenge Ridge, Dome Peak, Sinister Peak, and Bannock Mountain.

Off to the east, we could see the multiple pyramids of Sitting Bull Mountain, our goal for tomorrow.

Day 2: After enjoying yesterday’s clear air and long-range visibility, we were dismayed to awaken to a morning of heavy smoke. Apparently, the winds had shifted overnight, and forest-fire smoke was now blowing in from the Pasayten Wilderness. Nonetheless, we loaded summit packs and headed down the Canyon Lake Trail.

After about 2.5 miles, the trail cut across the toe of West Sitting Bull Basin, and we veered off toward our objective peak.

Steep heather slopes led us upward for about 1000 feet to a morainal bowl directly below the main and south peaks of Sitting Bull Mountain. We groveled up a steep, loose, scree gully to gain a high notch between the two peaks.

From the high notch, we made a short traverse over to a cleft in the cliff above us. Based on information provided by Fay, who had climbed Sitting Bull Mountain the year before, we knew that the face immediately left of the cleft was a feasible route. We roped up and used running belays up the rock face, placing several stoppers along the way. Although the face was well-broken with small ledges, most of the ledges were uncomfortably sloped downward and strewn with rubble, putting this part of the climb in a Class 4 category.

Above the crux face, we unroped and scrambled Class 2-3 rock to the jagged summit (5.0 hours from camp).

The forest-fire smoke limited our views to nearby peaks, such as Plummer Mountain to the south...

... and Agnes Mountain to the north. We found Fay’s register in the summit cairn and noted that nobody else had signed in since her climb in September 2016. It was no surprise that this somewhat remote and scrappy little peak is seldom climbed.

We descended by way of our up-route, being extra careful while down-climbing the Class 4 rock face. It was late afternoon when we reached our camp on Miners Ridge (4.5 hours from summit), so we hurriedly packed up and hiked back over Miners Pass. A few rays of evening sun poked through the smokey sky as we followed the trail around Image Lake Basin.

An hour of hiking took us to well-used Lady Camp, about 1.5 miles east of Image Lake. We erected our tent next to the trail and tried to imagine what Glacier Peak would look like without the smokescreen in front.

Day 3: We awoke to more heavy smoke to the south and west, but patches of blue sky to the east. Our goal for the morning was to climb Plummer Mountain, which stood closely to the northeast of camp. On our way toward the peak, we discovered that one of the amenities of Lady Camp is a red recliner lounge. No doubt this was left, either intentionally or not, by a horse packer. Perhaps a television will appear soon.

From Lady Camp, the easiest route up Plummer Mountain is to ascend grassy slopes in a northeasterly direction for 1000 feet until encountering the southeast ridge. This ridge leads up to the summit ridge, which comprises a half-dozen or more pinnacles.

The highest pinnacle involves a short Class 2-3 scramble to the summit (1.6 hours from camp). We found Fay’s register from last year and were surprised to see that only three people had signed in since then. The easy access and minor difficulties of this peak would suggest more summit traffic than six people in one full year.

Views were again restricted by the smoke, but the summit pyramid of nearby Sitting Bull Mountain was very visible and highly impressive.

We returned to Lady Camp, packed up, and headed out at noon. Our exit route took us down switchbacks to Miners Cabin Trail, then eastward for 4.5 miles to intersect the Suiattle River Trail. The weather forecast called for rain starting in late morning, but the first drops held off until mid-afternoon and never really got too serious. We put 6 miles of wet river trail behind us before pulling into a roomy forest camp at 6:00pm, about 4 miles from the trailhead.

Day 4: After a night of fairly steady rain, we were pleased to awake to only light sprinkles. The final 4 miles of trail was a breeze in our lightweight sneakers. For my old white Nikes, which were headed directly to the trash can, it was a glorious ending to a long and proud career.

Approximate Stats: 46 miles traveled, 11,600 feet gained and lost (in four days).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Middle Lakes High Traverse and Bear Mountain Attempt

Aug 30 - Sep 5, 2017

Bear Mountain attempt (7931')

For this year’s Labor Day Weekend trip, Eileen and I were joined by Fay, Lisa, K.Lo, and K.Ko for a journey into the northwestern corner of North Cascades National Park. Our goal was to climb Bear Mountain in the Chilliwack Mountains using the southwestern portion of the Redoubt High Route as an access line. We didn’t quite make the summit of Bear Mountain, but we experienced some incredible alpine scenery along our “Middle Lakes High Traverse” .

DAY 1: We pulled into the Hannegan Trailhead parking lot at 10:30am and were immediately faced with some difficulty finding a parking spot. This being a Wednesday morning served as an indicator of the popularity of the Hannegan Pass Trail. We split up group gear, shouldered backpacks, and headed up the trail. My main task for the day, aside from repeatedly putting one foot in front of the other, was to ensure that the corn chips lashed to the top of Eileen’s pack remained well protected. A helmet seemed to be in order here.

We cruised over Hannegan Pass in the afternoon heat and then descended 6 miles to U.S. Cabin Camp (6.6 hours from TH), where we bedded down for the night.

DAY 2: After breaking camp, we made a short hike over to the Chilliwack River cable car, made the amusement-park-like crossing, and then continued on to Brush Creek. This segment of trail had been littered with blowdown trees last year, but the trail crews had since done an excellent job of cutting logs and trimming back brush.

We hiked 6 miles up Brush Creek to Whatcom Pass (6.2 hours from Camp 1), at which point we turned left onto a steep but well-trodden path heading to Tapto Lakes. Several hundred feet up, we veered right and followed a secondary path over to Middle Lakes. The terrain here opened up to beautiful meadows of heather and white granite talus.

Just before reaching Middle Lakes, we stopped on a large heather plateau and set up camp.

Lower Middle Lake (is that an oxymoron?) sat below us, amidst a carpet of greenery. Upper Middle Lake sat closely above in a talus bowl. We all took a dip in the lower lake to wash off the day’s sweat.

Our campsite kitchen was a rounded granite boulder that provided a most spectacular view of Mt. Challenger. We could hardly take our eyes off the mountain long enough to eat dinner.

As the evening rolled on, a gibbous moon rose over the mountain, and soft alpenglow washed over the Challenger Glacier. The entire view seemed like a painted mural - too perfect to be real.

DAY 3: More alpenglow was highlighting Whatcom Peak when we arose the next morning. This craggy peak - usually lost in the legendary shadows of Mt. Challenger - never looked as good to me as it did now.

We broke camp and hiked around Lower Middle Lake, which nicely reflected the snowy slopes of Wiley Peak and the dark wedge of Luna Peak.

A short rising traverse brought us to the shore of aptly named Tiny Lake. Don’t be fooled by the name of this diminutive pond; it offers a hu-u-u-u-ge view of Mt. Challenger and Wiley Ridge. I think we all instantly fell in love with it.

More traversing on a sketchy boot-path took us over a spur ridge and down to a slope overlooking East Lakes. I found Lower East Lake to be especially scenic, due to its variegated colors and deep green surroundings.

After stopping between the two lakes to cool off and water up, we contoured above the lower lake ...

...and began a long northeasterly traverse above the Pass Creek valley. All traces of boot-path and other human presence were left behind; once beyond East Lakes, we saw nary a footprint or cairn.

About 3/4 mile past East Lakes, our traverse route crossed over a rocky rib that gave us a first look at Mt. Redoubt, Pass Lake, and a 5800-foot saddle between Pass Creek and Indian Creek. The saddle didn’t appear too far away, but it still took us over 2 hours to make the tedious side-hill traverse.

Upon arriving at the 5800-foot saddle, we could see Bear Mountain up to the left and Indian Basin down to the right. There was a mile of forest between us and the basin, but we really didn’t think it could be all that bad. Perhaps we should have known better: that mile of forest proved to dish up 2 hours of pure misery for us! Due to a combination of poor route choices and bad luck, we ended up in horrible brush and scrub cedars, with wasp nests scattered throughout.

It was around 6:00pm when we stumbled into Indian Basin (9.4 hours from Camp 2), feeling thoroughly thrashed from our bushwhack. The final cost was 2 lost trekking poles, 10 wasp stings, and countless bloody scratches. As a final insult, the basin had no flat campsites; the surface consisted entirely of talus and lumpy heather. Nonetheless, we all managed eek out reasonably comfortable tent pads by moving rocks and filling holes with gear. Interestingly, the only sign of previous humans in the basin was a solitary clothing button that had been left on a rock near our camp. We speculated that Indian Basin (soon to be renamed First Nations Indigenous Peoples Basin?) probably goes several years between visits.

DAY 4: Our climbing day began with clear, blue skies. From camp, we all hiked up a heather and talus slope to reach a saddle between Indian Creek and Bear Creek, then we turned left and followed the smooth ridge southwestward to a rocky knob. The stupendous northeast face of Bear Mountain came into full view here.

The entire Picket Range sprawled out to the south of us ...

... and Mt. Redoubt rose to the north of us.

After traversing farther along the ridge, more of the American Chilliwack Mountains came into view. We looked across at Mt. Redoubt, Mt. Spickard, and the Mox Peaks, as well as down at Bear Lake, which must certainly be a lake-bagger’s holy grail. Lisa and K.Lo decided to stay and enjoy the view from here, rather than continuing on toward Bear Mountain.

Fay, K.Ko, Eileen, and I began traversing along the craggy east ridge, staying mostly on the southern side. We followed a series of ledges past several ridge horns until the crest steepened, at which point we angled down to a scree slope that stretched beneath the cliffs.

After traversing across the scree, we climbed a Class 2-3 gully that led back up to the ridge crest. We could see the large summit block ahead, but it was a slow process getting to it.

Farther along, the ridge crest became very narrow and steep. We could peer over the edge and see that the north face was considerably overhung. Yikes!

More roped traversing along a series of Class 3-4 ledges ended in a steep gully, which we climbed to a deep “V” notch between the two summit pinnacles. It initially appeared that the southeast pinnacle was higher, and this caused a false start until we realized that the northwest pinnacle is the true summit.

We were dismayed to see that the true summit pinnacle begins with a steep dihedral and then transitions into a vertical face above. This would involve mid-Class 5 climbing that exceeded our exposure tolerance and meager gear. We sadly ended our climb here, only 100 feet below the summit, and turned around at 5:00pm.

Our traverse back along the ridge took us through the evening, which featured dramatic alpenglow on the Picket Range. Darkness caught up to us just before we began our final descent into Indian Basin. Lisa and K.Lo signaled us into camp with their headlamps.

DAY 5: We left Indian Basin and headed back up to the 5800-foot saddle, breaking into two different groups along the way and taking different routes. The “low route” seemed to play out better than the “high route” (despite more wasp stings), but both routes were an improvement on our previous incoming route. From the saddle, we generally retraced our steps back over to East Lakes. The mid-afternoon heat demanded a swim in the lower lake.

In my opinion, Lower East Lake is the finest gem of the lakes that we visited on this traverse. It has great views, an inviting shoreline, and magic water.

By the time we reached Tiny Lake, everyone was ready for another swim. The water here was surprisingly cold and clear. Oh, did I mention the view?

We eventually left Tiny Lake and made our way back over to Middle Lakes, where we again camped on the heather plateau. While eating dinner, we watched a towering smoke plume form on the eastern horizon. No doubt this was the Diamond Creek fire currently burning in the Pasayten Wilderness.

DAY 6 & 7: The winds had shifted during the night, and we awoke to hazy skies. As we hiked down to the Chilliwack River and up to Boundary Camp for our final night of the trip, the smoke became increasingly thick. By the following morning, visibility was a scant 1/2 mile at Hannegan Pass. We finished our hike down to the trailhead in a gloomy fog.

Approximate Total Stats: 54 miles traveled; 16,300 feet gained and lost; 13 wasp stings suffered.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Black Peak and Corteo Peak

August 4-7, 2017

Black Peak (8970′)

Corteo Peak (8080′+)

For our 15th annual Mid-Summer Climbing Trip, I teamed up with Jon, Todd, Eric, and Adam for a bid on Black Peak and Corteo Peak near Rainy Pass. This was actually a consolation trip, because our original plan was scuttled by the pervasive heat and smoke. If we initially wondered how much fun could be had when an extreme-heat warning coincides with an air-quality advisory, the answer soon became pretty clear: A lot! An unexpected benefit of the heavy smoke was that it filtered out most of the sunlight, so the forecasted extreme heat never manifested itself.

Day 1: We arrived at the Lake Ann Trailhead before noon and were immediately struck not only by the poor visibility but also by the strong odor of wood smoke hanging in the air. Remarkably, we became desensitized to the smell within a half hour and never really noticed it for the next several days. We hiked up and over Heather Pass and down to Lewis Lake, which called out for a cooling dip. Then it was onward to Wing Lake, where we established camp on a larch knoll above the north shore. The lake was still partially iced over, but that didn’t keep us from taking another cooling plunge. The 32-degree water here made for a very quick plunge. Because the bugs (gnats, mosquitoes, and flies) were so bad in camp, we ate dinner next to the chilly lakeshore, underneath the smokey-gray face of Black Peak.

Day 2: We awoke to see heavy smoke everywhere except for a patch of pale blue sky surrounding Black Peak. This atmospheric auspiciousness was the only motivation we needed to head for the summit.

We circled around the lake and ascended an easy snow couloir that led to the south ridge. There was a solo climber ahead of us and a pair of climbers behind us; otherwise, we had this very popular mountain to ourselves.

From above Wing Lake, we could see that it was approximately 70-percent ice covered ... but melting out quickly.

After reaching the south ridge, we turned right (north) and ascended a broad scree-and-talus chute for about 1000 feet.

At a high platform above the chute, a rightward traverse took us around to the northeastern edge of the summit block. A short Class 3.5 scramble on good rock led to the top.

We reached the summit in late morning (2.1 hours from camp). Visibility was limited to a scant mile, but Black's craggy satellite peaks were impressive in the ominous haze.

We made a leisurely descent to camp, arriving in the early afternoon and discovering a party scene at Wing Lake. There were a dozen or more tents pitched around the lake, and more people were rolling in every half hour. The troops included six climbers who were in the middle of a marketing photo shoot for MSR equipment. You might guess that the abundance of people and pleasant weather would devolve into alpine hijinks, and you would be correct. One person from the MSR group ended up on a small iceberg in the lake and then spent an hour trying to paddle back to shore. This whole raucous environment was quite a contrast to the previous quiet afternoon.

Day 3: We awoke with high hopes of seeing clear skies all around, but it was just as smokey as ever. The rising sun hung in the sky like a Martian orb (although none of our cameras detected the strong red color).

By the time we left camp, small patches of semi-clear sky were letting some sunlight through. We descended several hundred feet to reach the bottom edge of the Lewis Glacier (now just a snowfield), then cramponed up to the top-left corner of the glacier, where snow laps onto a level shoulder.

We crossed over the shoulder and ascended a steep slope covered with sand, talus, and snow. This slope ended at a 7600-foot gap in Corteo Peak’s northwest ridge.

We followed the ridge crest downward for a hundred yards to a lower gap, then descended steep but easy sand slopes to the large western cirque. From the cirque floor, a beeline was made for a deep notch in Corteo’s south ridge.

At the notch, we roped up and began simul-climbing along the south ridge crest. This ridgeline offers enjoyable Class 3-4 scrambling on blocky granite, with a few zones of shattered rhyolite tossed in to keep things interesting.

We reached the roomy summit in early afternoon (4.7 hours from camp). Visibility was slightly better here than on Black Peak the previous day.

We carefully down-climbed the ridge crest with the protection of running belays, then retraced our back across the cirque, over the northwest ridge, and down the Lewis Glacier. It was early evening when we arrived at camp, and by now all of the weekend hikers and climbers had packed up and left. The lake once again felt peaceful and silent. We ate dinner on a rocky projection and watched the filtered evening sun wash over Corteo Peak, while Eric vainly tried to explain the meaning of transfinite numbers, surreal numbers, and aleph-one. Perhaps we were too distracted by the alpine ambiance.

Day 4: The morning sky was again very smokey except for a deep blue patch around Black Peak. We were packed up and ready to hike out by 7:45am. it was interesting to see that a veneer of ice had formed on Wing Lake during the night, confirming our feeling that this was a cold lake!

Approximate total stats: 15 miles traveled; 8000 feet gained and lost.

0 notes

Text

Mount Fernow in the Wild Sky Wilderness

July 15, 2017

Mount Fernow (6190′)

Alpine Baldy

On Saturday, Todd joined me for a climb of Mt. Fernow in the Wild Sky Wilderness. This peak had caught my gaze many times before, but I never made an attempt until now. Todd had climbed it 25-odd years ago while living in Skykomish and decided that a repeat performance sounded good. It turned out to be a scrappier trip than I expected and he remembered, although that was largely of our own mis-doing. It was also a day of surprises and revelations.

Going on Beckey’s description for the “southwest route”, we drove up Road 66 without knowing what kind of road conditions we’d encounter. Surprise No. 1: This road has been maintained in excellent condition because it leads to the new Jennifer Dunn Trailhead. This trailhead had never hit our radar. Surprise No. 2 was the newly built trail that leads from here up Beckler Peak. Huh! didn’t know about that either. Surprise No. 3: Road 6610 is blockaded at the trailhead, so there is no chance for motorized progress beyond, as was previously done.

We quickly shifted gears and started hiking up the new Beckler Peak Trail. At the 3900-foot Beckler-Baldy Saddle, we left the trail and headed easterly up steep forest. At 4700 feet, the dense forest opened onto a vast green hillside of ferns and huckleberry bushes.

In various places, the hillslope was ablaze with floral color. It appeared that we’d hit the wildflowers near their prime.

We contoured around to the northeast until the forested summit of Alpine Baldy came into view. Then came Surprise No. 4: The unmistakable line of a trail could be seen cutting across the open face of Alpine Baldy. This trail was not shown on any map we’d ever seen.

We traversed over to the trail and followed it past the summit until close to Alpine Baldy’s southeast ridge. It had the appearance of being very new and nicely built.

Looking back whence we'd come, the trail could be seen ending abruptly in the middle of the open hillslope. This was all very perplexing! The vivid greenery was also strikingly beautiful! There is no doubt how Alpine Baldy earned its name.

We soon left the trail and hiked northwesterly up to Baldy's summit (2.6 hours from TH) and then down the north ridge. Although older editions of Beckey’s book describes this ridge as “easy”, we found that it quickly turns into a narrow, craggy crest with lots of Class 3 scrambling, none of which Todd remembered from 25 years ago (Surprise No. 5!). We were frequently forced to drop below horns and then climb back up. Although not really difficult, it was certainly tedious and time-consuming. On the positive side, Mt. Fernow showed itself clearly for the first time.

Rather than continuing up the craggy ridge to Point 5403, we decided to descend 200 feet and traverse over to Jake’s Lake. This was an error; the side-hilling was slow and awful. It was a relief to get past Point 5403 and stumble across a fisherman’s path that led to Jake’s Lake (4.8 hours from TH). From the lake, things became much easier. We ascended 1000 feet in a rocky and heathery couloir on Mt. Fernow’s south face.

At the top of the couloir, we turned right and continued a short distance on the ridge crest to reach the summit (5.8 hours from TH).

The summit is a cluster of large granite blocks that would make a fine bivouac spot. Surprise No. 6 was discovering that the summit register had been placed by Kevork, the well-known North Cascades National Park climbing ranger. I wonder what brought him this far south to a somewhat obscure peak?

Mt. Fernow sits between three groups of major peaks: The Skykomish Mountains to the west ...

The Monte Cristo Mountains to the north ...

And the Snoqualmie Mountains to the south.

I particularly liked the view of Cathedral Rock, Mt. Daniel, and Mt. Hinman from here.

0 notes

Text

Big Snow Mountain Carryover

July 8-9, 2017

Big Snow Mountain (6680′)

I teamed up with Lisa L. last weekend for a climb of Big Snow Mountain in the western Alpine Lakes Wilderness. To increase the variety factor of our climb, we did a carryover loop - entering via Dingford Creek and exiting via Hardscrabble Creek - and added a summit bivouac. The total loop turned out to be more challenging than we expected, but it had the feeling of a remarkable adventure route in our own backyard.

Day 1: We hiked up the Dingford Creek Trail to Myrtle Lake, then thrashed our way through dense brush in a southeasterly direction to intersect the stream draining Big Snow Lake. This stream pours down a steep, boulder-filled defile between tall cliffs. The ascent starts out with easy boulder hopping but gradually turns into some interesting Class 3 scrambling on wet, mossy rock. At 4900 feet, we suddenly popped out at beautiful Big Snow Lake (6.0 hours from TH), with its vertical granite faces plunging into deep blue water.

On the near shore, the water turns to a jade-green color, and scattered lakebed rocks show through the translucent surface. My brother Brad calls this “magic water” and I couldn’t agree more.

After a cooling dip in the lake, we followed a path to the right in a counter-clockwise direction around nearby Snowflake Lake and up to a heather bench. When the bench ended at the base of a moderately steep stream gully, we went straight up on snow and Class 2-3 rock. This was Lisa’s least favorite part of the trip, but at least it was fairly short.

The unpleasant stream gully deposited us on easy snowfields about 1000 feet below the summit of Big Snow Mountain. It was a straight-forward boot ascent from there.

Along the way, we passed an interesting rock formation on the mountain’s northwest slope. I thought it looked like a tuning fork, whereas Lisa thought it looked like a raptor. Perhaps it’s a raptor perched on a tuning fork.

We arrived at the summit around 6:00pm (9.8 hours from TH). The register here is a thick notebook inside a waterproof plastic box. It appears that this peak gets a half-dozen or so parties per year, with approaches split between Myrtle Lake, Hardscrabble Lakes, and Gold Lake.

I would have to declare that Big Snow Mountain must be one of the finest viewpoints in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. When standing on its summit, the entire chain of craggy Snoqualmie peaks - from Mt. Daniel to Kaleetan Peak -stretches out in front of you like a chorus line.

The 70-degree evening weather called out for snow-margaritas, and we were in no position to decline.

The summit features four good, level bivouac spots, each with a view of the surrounding mountains. As a bonus, we found running water in a heather meadow only 50 feet below the top.

Sunset coincided with a full moonrise over Chimney Rock and Lemah Mountain.

Day 2: We awoke to sunrise on Mt. Rainier and clear skies overhead.

Our descent route followed the long northeast shoulder down to an obvious 5700-foot gap in the ridge. The morning snow was just firm enough to warrant crampons.

From the gap, an easy snow couloir led down toward Upper Hardscrabble Lake.

The snow ended about 500 feet above the lake, leaving us to pick our way around cliff bands and down talus slopes. At the lake (3.2 hours from summit), we met two campers who gave us some good information about getting down to the Middle Fork Road.

A well-defined footpath leads from the upper lake down to the lower lake, staying on the right (north) side of the outlet stream the whole way. We circled around the head of Lower Hardscrabble Lake and crossed multiple inlet streams to reach the western shore.

Does anybody remember “The Great Trog” of Nooksack Cirque? This 8-foot-high boulder could be called “The Little Trog.”

There is a footpath leading down-valley from Lower Hardscrabble Lake, but the first 1/2 mile is very vague and difficult to follow. Eventually, the forest and brush open onto a large boulder field, which is well marked with ducks and cairns.

Beyond the boulder field, the foot path becomes very well-trodden and easy to follow. We quickly descended the remaining 1000 feet to the Middle Fork Road, which we intersected at a point closely west of its terminus (6.6 hours from summit). I’ve never been a fan of road walking, but this 7-mile segment from Hardscrabble Creek to Dingford Creek is about as smooth, shady, and pleasant as a dirt road can be. Of course, that didn’t stop me from whining and complaining the entire way.

We reached our car at the Dingford Creek Trailhead shortly before 5:00pm (9.9 hours from summit), laden with blisters, sore knees, and great memories.

Total stats: about 20 miles traveled; 5500 feet gained and lost.

0 notes

Text

Gunsight Peak and Sinister Peak

June 29 - July 4, 2017

Gunsight Peak (8198′)

Sinister Peak (8440′)

Over the long Independence Day weekend, Kevin K. and George W. joined Eileen and me on a six-day climbing adventure into the Glacier Peak Wilderness. Our goal was to climb Gunsight Peak and Sinister Peak. Eileen was the trip architect, and the rest of us were along to do the heavy lifting. We were fortunate to have beautiful weather (except for a few foggy hours on Day 4), scant bugs, and no other people for the first three days.

Day 1: Having driven up the Suiattle River Road and car-camped at the Downey Creek Trailhead on Wednesday night, we were able to get an early start sorting gear and arranging backpacks on Thursday morning. Our peak goals required lots of snow gear, rock gear, and glacier gear, including two full-length (60m x 9mm) alpine ropes. This did not make for a lightweight trip.

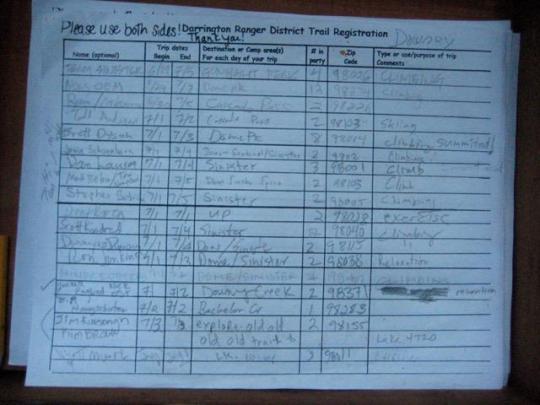

At 8:00am, we shouldered heavy packs and started up the Downey Creek Trail, stopping along the way to sign the trail register. It was a brand new register, and our party ”Team Sinister” was the first to sign in this year. The trail is in very good condition except for a dozen or more blow-down logs and numerous mudholes. We crossed Bachelor Creek on a large foot log shortly after noon (4.3 hours from TH), then began a hot, slow slog up the abandoned Bachelor Creek Trail. In a brushy area near elevation 4100 feet, we crossed back over Bachelor Creek on another foot log and continued up the now-very-overgrown trail through a series of slide alder thickets. Our day ended at an informal but well-used forest camp in "Bachelor Flats” near elevation 4500 feet (9.7 hours from TH).

Day 2: We were packed up and moving again by 8:00am. The old trail took us through the boggy flats and then up a steep blowdown area before curving into the welcome basin of Bachelor Meadows. Snow slopes led up to Cub Pass, and bare slopes led back down to still-frozen Cub Lake. A recent avalanche or mudslide has obliterated part of the old trail here, but the route is not difficult to follow down to the lake outlet (3.7 hours from Camp 1).

We continued up through Cub Lake Meadows and over Itswoot Ridge, then made a long traverse over to the Dome Glacier. Snow coverage was approximately 95 percent.

We continued up through Cub Lake Meadows and over Itswoot Ridge, then made a long traverse over to the Dome Glacier. Â Snow coverage was approximately 95 percent.

By staying high on the Dome Glacier, we were able to skirt all of the large crevasses. The prevalent “hairline” crevasses were easily stepped over.

It was late in the day when we rounded a bergschrund and climbed the final snow finger to the 8500-foot Chikamin-Dome col (11.6 hours from Camp 1).

There is a well-established campsite at the Chikamin-Dome col, with enough room for a small tent or several bivouac sacks. After a half-hour of earthwork, we were able to enlarge the site sufficiently to accommodate George’s four-person pyramid tent.

From our high camp, we watched a pink glow wash over the ominous black rock of Agnes Mountain...

... and the friendly gray granite of Gunsight Peak.

Day 3: Following a surprisingly calm night at the high col, we broke camp and headed down the Chikamin Glacier. The uppermost part of this descent oftentimes involves some technical trickery to get over the bergschrund, but we were delighted to find a walk-off route due to the heavy snowpack this summer. A 90-minute descending traverse took us to a 7000-foot snow dome and rock outcrop closely below the shadow of Gunsight Peak.

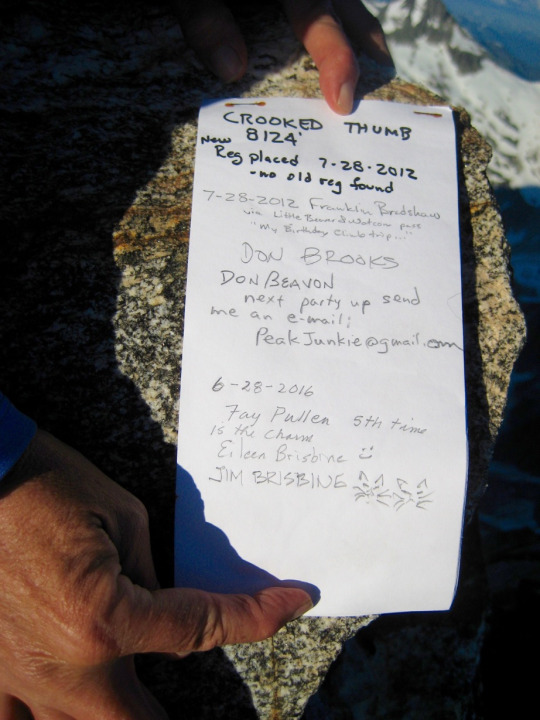

After dropping off backpacks at the outcrop and loading summit packs, we booted up to a snow finger between the main and south spires of Gunsight Peak. Kevin and George studied the beta graciously provided by Fay Pullen, who had climbed the main spire last year, and were able to scope out a good route for us.

From a breach in the snow finger, George led up a short wall to a broad ledge, then leftward to a steep dihedral of black rock. The uppermost 15 feet of the dihedral features exposed 5.6 moves over solid granite and was the technical crux of our route.

Once past the crux, we traversed farther leftward on Class 3 granite to enter a distinctive dike of reddish-black basalt. This dike provided a somewhat loose but fairly easy scrambling route to a high notch that separates the main and north spires.

Because a vertical headwall prevents a direct climb out of the main-north notch, we descended about 20 feet and then made a rightward traverse across steep, solid, well-broken rock to reach a shallow, parallel gully. This deviation was not immediately obvious to us, so we actually spent a couple extra hours trying to tease out the correct route.

A series of short chimneys and cracks ranging up to Class 5.5 ended at the ridge crest adjacent to a large horn adorned with numerous rappel slings. This rappel station provided a welcome confirmation that we were truly on route.

The narrow ridge crest involves wildly exposed but very enjoyable climbing over a jumble of large and remarkable solid granite boulders, with moves ranging from Class 3 to low Class 5. We topped out at 6:30pm (7.1 hours from Camp 3). The slightly lower north spire towered nearby.

The summit of Gunsight Peak is a tiny horn of rock roughly the size of a barstool. We had to take turns tagging the horn.

To the west, Sinister Peak rose out of the Chikamin Glacier like a breaching whale.

We belayed each other back down the exposed summit ridge, then made a double-rope rappel down the west face. From there, we were able to scramble down several hundred feet to the top of the black dihedral. Kevin led off a diagonal double-rope rappel, putting in directional protection along the way, which allowed us to reach the snow finger in one shot.

The sun was just dropping below the horizon as we descended soft snow back to our campsite on the glacier (2.8 hours from summit). As a team, we solidified our reputation for somehow managing to use up every available minute of daylight on every climb.

Day 4: After another starry night, we awoke to cloudless skies and a frozen snow surface. Our group was in no hurry to leave this superb campsite, so it was 10:00am before we were packed and ready to go.

We made a rising traverse back across the Chikamin Glacier, aiming for the Dome-Sinister saddle.

Our traverse route took us through the deposition zone of an avalanche that had recently occurred on Sinister Peak. This avalanche originated as a triangular snow patch high on the mountainside. None of us had ever seen such a clearly defined origination zone

At the Dome-Sinister saddle, we encountered three climbers who had just traversed over from Cub Lake this morning. They headed up Sinister Peak’s west ridge, whereas our group elected to follow the traditional southwest route. We contoured around the ridge on an easy snowfield and then climbed up to a prominent gully. This turned out to be one of the loosest, most unpleasant gullies we’ve ever had the displeasure of climbing, and none of us was eager to descend the same way.

With the ugly gully behind us, we enjoyed a Class 2-3 scramble along the upper west ridge. The other party was far ahead of us at this point.

We reached the roomy summit in early afternoon (3.4 hours from Camp 3) and spent a long time taking in views of the surrounding peaks. This included the gray faces of Gunsight Peak to the east...

... and the Ptarmigan Traverse peaks to the north.

On descent, we retraced our route down the upper west ridge.

Rather than down climb the ugly gully, we followed the other party down the lower west ridge. This relatively new route involves some white-knuckle Class 3-4 scrambling on semi-solid rock. A fixed sling had been placed at one particularly tricky location, and there was considerable exposure along much of the route. We were happy to finally reach the gentle slopes of the Dome-Sinister saddle.

The remainder of our day consisted of a 1400-foot ascent to the Chikamin-Dome col, then a long traverse back over to Itswoot Ridge and down to Cub Lake. Many climbers had made this traverse during the past two days, so we merely followed the snowy freeway.

Five or six climbing parties were camped on Itswoot Ridge, and another 10 or 15 parties were camped in Cub Lake Meadows when we arrived at 8:30pm (6.5 hours from Sinister Peak summit). That night, the dozens of shining headlamps gave the meadows a party atmosphere.

Day 5: Although light fog had hung over the meadows throughout much of the night, it was completely gone by morning. We had a leisurely breakfast in the sun before Kevin and George wandered off to chat up some of the other campers. One party comprised a dozen NOLS instructors and students, all heading over to Dome Peak. We were also surprised to see two trekkers carrying backcountry skis and wearing telemark boots. This pair turned out to be James Hamaker and David Burdick, who were just completing a ski version of the Ptarmigan Traverse.

Eventually, we were packed up and heading over Cub Pass. We followed the well-beaten trail down through Bachelor Meadows to the 4500-foot forest camp in Bachelor Flats. However, rather then staying on the old trail from here, we crossed Bachelor Creek and descended heavy forest parallel to the creek. Recent beta indicated that this north-side route has recently become the preferred option, and we would certainly concur. Even when the forest gives way to thick slide alder, a hacked-out boot path provides fairly easy travel down to the main trail at about 4100 feet. Had we discovered this new route on Day 1, we could have saved ourselves some time and frustration. Oh well...next trip!

By the time we reached Downey Creek, it was nearly 6:00pm, so we all agreed to spend another night in the forest rather than hoofing 6.5 miles out to the trailhead. A small campsite 3 miles farther down the trail (9.0 hours from Camp 4) served us well for our last night out.

Day 6: We were all up at first light and ready to go by 6:15am. In the cool of the morning, the remaining 3.5 miles of trail seemed like an easy stroll. This is always my favorite way to end a long mountain trip.

Just before reaching the trailhead, we stopped to look at the trail register. It immediately confirmed our impression that many, many people had come up to Cub Lake and beyond: a whopping 18 parties - a total of 54 people - had signed in behind us this weekend! Team Sinister was honored to have led the charge.

Total stats: 34 miles traveled; 14,000 feet gained and lost.

0 notes

Text

Silvertip Mountain and Mount Rideout Attempt

May 26-28, 2017

Silvertip Mountain (8517′)

Mount Rideout attempt (8028′)

When we were handed the best Memorial Day Weekend weather forecast in quite a few years, Fay, Kevin K, George, Eileen, and I jumped on the opportunity and headed north of the border. Our goal was to climb Silvertip Mountain and Mt. Rideout in British Columbia. Silvertip Mountain is the highest peak in the Canadian Cascades and, as Fay explained, is also the most prominent non-volcanic peak in the northern Cascades (in this context, meaning everything north of the Columbia River). Although not a lot of Washington climbers know of Silvertip Mountain, a lot of them have probably seen and admired its pyramidal countenance from Washington summits. Mt. Rideout is even less familiar, but as a climbing objective, it usually pairs well with Silvertip—like filet mignon and cabernet sauvignon.

DAY 1: We drove the Silver-Skagit Road approximately 22 miles southeast from Hope, B.C., went slightly past the Maselpanik Creek road, and turned onto an obscure spur road that quickly ended in a small parking lot at the edge of the valley (Elev. 2000 feet). It was high noon and quite warm (hot, by May standards) when we arrived. We finished sorting gear, shoulders packs, and then headed up with full water bottles.

Our first leg of the approach involved a hot, sweaty slog for 700 vertical feet up a clearcut directly above the parking lot. This clearcut slope is steep and rocky but, surprisingly, not at all brushy. Near the top, we veered left onto a faint climber’s path that led up to a rib. The final few feet went up a very steep Class 3 rock and dirt headwall with a fixed handline. We took our first of many rest breaks at the top of this portion, about 1000 feet above the parking lot.

Once past the steep headwall, the gradient relaxes slightly and the climber’s path becomes somewhat better defined. We followed boot tread and numerous bits of orange flagging onward and upward along a ridge crest for several hours. The travel was never difficult or brushy, but it was (in a clinical sense) totally unremarkable: just a long, monotonous forest slope. At a rock step around Elev. 4600 feet (4.5 hours from cars), we encountered our first good view of the surrounding peaks. Shortly beyond, the ridge forms a rocky hogback with a huge, old, gnarled fir tree growing out of the side.

At 5300 feet, the ridge crest relaxes even more and the views open up completely. This is also where we encountered a thick snow cover.

Progress along the ridge crest is blocked by a rock buttress at 5800 feet, forcing a detour around to the right (eastern) side of the ridge. We traversed a series of steep snow slopes around the buttress to gain a snowy basin below Silvertip Mountain. Some of the traverse route crosses between tall cliff bands; this is no-slip territory!

We filled up our water bottles and carboys at a meltwater trickle in the snow basin, then continued up to the ridge that connects Silvertip and Rideout. Despite a healthy snowpack this winter, prevailing southerly winds have kept the ridge crest bare and dry. We happily set up camp on some gravel benches with sweeping views of the Cascade range to the north and south (8.4 hours from cars; 5000 feet gained).

DAY 2: We awoke to blue skies and warm weather, which allowed for a full breakfast-time appreciation of Silvertip Mountain to our east...

... and Mt. Rideout to our west.

After breakfast, we packed up rucksacks and headed out to Silvertip Mountain. Our route generally followed the long, curving, west ridge, which features inviting alpine tundra and craggy outcrops. I found the terrain to be very reminiscent of the scenic ridge between Windy Pass and Mt. Cashmere. We all agreed that this qualifies as a “glamour climb” for peak baggers!

About a mile along the crest, we crossed over the top of a rocky false summit. This required some exposed Class 2-3 scrambling on the back side but was never difficult enough to warrant a rope.

Shortly past the false summit, we donned crampons and started zig-zagging up moderately steep snow slopes on the southwestern face of the true summit. Snow conditions were quite variable here, ranging from firm and crusty to soft and mushy. It became clear that our late-spring snowfall has not yet consolidated ... and probably never will before melting off.

The final few hundred feet leading to the summit was a slightly steeper snow chute. Knowing that this is likely an unpleasant scree chute later in the season, we were happy to have good snow cover.

We topped out just in time for an extended boots-off lunch break (3.0 hours from camp). There was no summit register, so we left a small tube.

Being the highest and most prominent peak in the region, Silvertip provides a splendid vantage point. The northern side of the nearby American Chilliwack mountains shown below (a view seldom seen by Washington climbers) was particularly impressive. The Coast Range extended off to our northwest, and the Coquihalla mountains rose directly to our north.

We descended via the same route and arrived back at camp in late afternoon. Because we still had a couple hours before dinner, Fay and Eileen and I decided to make a reconnaissance trip up Mt. Rideout. We dropped down to the Silvertip-Rideout Col, then made a left-slanting traverse up Rideout’s eastern face. The snowfields provided good travel, but these soon gave way to a series of wet, mossy, rock outcrops. We eventually decided that this route was too unappealing for a summit bid, so we retreated to camp and enjoyed a sunset dinner with George and Kevin.

DAY 3: The morning was again clear and sunny but now a bit breezy. After breakfast, our entire group decided to make another attempt at Mt. Rideout. This time, we tried climbing more directly upward until closely below the summit block and then traversing leftward on the highest snowfields. Our plan worked nicely for the first 800 feet, at which point the slope steepened and the snowpack became very unconsolidated. While trying to kick steps up a little chute, I triggered a snow slough that raced down our ascent route. We pulled the plug immediately after this scary incident and later agreed that mid-summer or autumn seems like a better time for a Rideout climb.

We retreated back to camp and quickly began packing up in anticipation of a long, tedious descent. We retraced our up-route across the steep snow slopes and down the ridge crest, following boot tread and flagging as best we could. For the most part, our descent was uneventful. However, during our final 700 feet down the clearcut, we all managed to take multiples slips and falls, collecting a variety of cuts and abrasions in the process. With great relief, we reached our cars at 6:00pm (5.6 hours from camp). How bad was it? Well, plans for a return trip started to form even before we finished treating our wounds.

0 notes

Text

Deadhorse to Grace Chiwaukum Traverse

Sep 29 - Oct 2, 2016

McCue Peak (6935′)

Big McWaukum Peak (7423′)

Jason Point (7123′)

Deadhorse Peak (7534′)

For our annual Golden Larch Trip, Eileen and I returned to the Chiwaukum Mountains to do an abbreviated variation on our recent Labor Day Weekend trip. We were joined by Doug, Todd, Kevin K, Kevin W, Kevin L, Lisa, Fay, Steve, and Deb for some or all four days.

Day 1: With eleven people and five cars in our group, we started the day by executing a complex car shuttle to leave four cars at the White Pine TH. This resulted in a staggered start up the Lake Ethel Trail. We eventually convened on a rock outcrop 6 miles up the trail. From there, we went cross-country to the Ethel-Eileen saddle and then ascended to the High Meadows above the Scottish Lakes. Camp 1 was established in a grassy basin below Mt. Baldy. Fortunately, there is no shortage of room here.

Day 2: Morning sun turned the grasses and larches in our basin a fiery red color.

Before breaking camp, we made a quick jaunt up McCue Peak (Point 6935) for some views across the High Meadows...

…and over to Big Chiwaukum Peak. The sky was strikingly blue due to recent rains.

After returning to camp, we packed up and headed out to Big McWaukum Peak.

"Big Mac" offers remarkably good views for such an easy ascent. Steve and Deb made this summit their turnaround point for the trip and headed back to the Lake Ethel TH.

We scoped out our route down to Larch Lake. Rather than dropping directly into Ewing Basin, we made a high descending traverse. Our group now had nine people, and we ended up with a similar number of variations on the descent route.

Our route passed by hundreds of schist boulders, some of which displayed amazing textures such as this.

By mid-afternoon, we all arrived at beautiful Larch Lake. K.Ko and Todd took advantage of the warm weather by plunging into the green water—although not for long.

Larch Lake sits in a basin with numerous ponds, tarns, and creeks. One could wander around here all day and keep finding scenic treasures such as this...

…and this. Many of the larch trees appeared to be at their peak of color, whereas others were either before or after their peak

Some of the schist outcrops had interesting shapes and details. The outcrop below presents an ominous simian face.

Having a couple hours of daylight before dinnertime, Eileen and Fay and I scrambled up Point 7123 east of Larch Lake. The summit of this rocky point overlooks the three Jason Lakes, so we dubbed it “Jason Point.”

Day 3: High-level winds during the night signaled an incoming weather front. We awoke to colder temps and partial cloud cover. Our agenda called for breaking camp and heading up to Deadhorse Pass. Along the way, we stopped at Cup Lake and admired the golden colors around Larch Lake.

From Cup Lake, there is a crude footpath leading up to Deadhorse Pass. Hikers crossing over this pass will find a large tube and sign-in booklet that was placed by the Scottish Lakes High Camp folks. To my knowledge, this is the only “pass register” in the Cascades!

Lisa and K.Lo were eager to get home, so they continued over the pass and down to the White Pine TH. The remaining seven of us scrambled up Deadhorse Peak closely north of the pass.

Deep-blue Larch Lake and its surrounding golden meadows were clearly visible from the summit.

Once back at the pass, we descended westward into Deadhorse Basin.

We stopped for a break partway down and had some fun with a nearby schistose “hoodoo.” This interesting feature could be called “Deadhorse Balanced Rock.”

In the lower basin, Eileen and Fay peeled off and headed down to the White Pine TH. The remaining five of us turned southward and headed to Grace Lakes. We contoured across open hillsides for a mile until encountering an old, partly overgrown sheepherder’s trail. This trail led directly to the lake basin.

We made camp in a bouldery lawn between the lakes. Although weather forecasts had predicted rain or snow today, and dark skies threatened us all afternoon, we never got more than a few light snow sprinkles.

Day 4: Following our coldest night of the trip, we awoke to a light frost on our tents and a layer of ice in our water bottles. Morning sun dramatically highlighted the Bull’s Head and Bull’s Tooth across the valley.

To exit Grace Lakes, we hiked back northward on the sheepherder’s trail for a mile, then descended huckleberry slopes to intersect the White Pine Trail. From there, 5 quick miles led to the TH and completed a very fun Golden Larch Trip.

#Chiwaukum#McCue Peak#Big McWaukum Peak#Deadhorse Peak#larch lake#grace lakes#golden larch#deadhorse pass

0 notes

Text

High Chiwaukum Traverse: Big Chiwaukum Peak

September 2-6, 2016

Big McWaukum Peak (7423′)

Big Chiwaukum Peak (8081′)

Ladies Peak (7708′)

Unsettled weather over Labor Day Weekend sent many of us scrambling for alternative trips. Eileen and I ended up doing a high alpine traverse through the Chiwuakum Mountains, hoping for better conditions. We had both spent several decades exploring the many nooks and crannies of the Chiwuakums, and this traverse served as a way to connect some of our favorite locations, such as Larch Lake, Grace Lakes, Ewing Basin, and the High Meadows of the Scottish Lakes. It also gave us access to the five principal summits of the Chiwaukum crest: Big McWaukum Peak (7423’), Deadhorse Peak (7534’), Big Chiwaukum Peak (8081’), Snowgrass Mountain (7993’), and Ladies Peak (7708’). Along the way, we were able to tuck in the three peaks that we hadn’t both climbed before.

Day 1: Our trip started by stashing mountain bikes at the Whitepine Creek TH, then driving over to the Lake Ethel TH. We headed up the well-maintained trail in the late afternoon. It was cool, windy, and a bit rainy during our 5-mile hike to Lake Ethel. We found a spacious and spotlessly clean campsite nestled in deep forest near the lake shore.

Day 2: Our second day began with partly clear skies and morning sun on the lake. This gave us some hope that the weather was improving, but it turned out to be a false hope.

We packed up and followed the trail toward a knoll above the lake, then went cross-country to reach a 6000-foot saddle between Lake Ethel and Loch Eileen. The former lake features a large, distinctive boulder sitting by itself out in the water, as can be seen in the photo below.

Several small cairns and faint boot tracks led easily through a short cliff band beyond the Ethel-Eileen Saddle. Soon we were strolling through the beautiful rock-and-larch gardens of High Meadows.

We wandered southward, crossing under the open slopes of Mt. Baldy and ending up at 6640-foot McWaukum Pass. This pass marks the “T” intersection of McCue Ridge and the Chiwaukum crest. Moody clouds created an interesting scene around us.

Big McWaukum Peak is a straight-forward ascent from McWaukum Pass, so we dropped packs and headed up the east ridge. The metamorphic geology throughout the Chiwaukum Mountains leads to some striking topography, as seen here. One side of this ridge is a uniform slope, whereas the other side drops off in a series of vertical steps and overhangs. Don’t try this one in the dark!

Everything to the west was fogged in, but we could see beautiful Larch Lake—our eventual goal for the day—to the south

After returning to McWaukum Pass, we descended a Class 2 ramp that spilled us out on a broad scree slope above Ewing Basin. Rather than dropping southward directly into the basin, we decided to traverse over to historic Ewing Mine located on the western side of the basin.

The mine has a well-preserved tunnel heading into the cliff. Someone with a pair of rubber boots and a bright headlamp could have a lot of fun exploring this tunnel.

It had been threatening to rain all day, and by late afternoon the drops came aplenty. We finished our hike into Larch Lake on a wet trail. Surprisingly, nobody else was camped at this popular lake.

Day 3: The rains subsided overnight, and we awoke to colorful, partly sunny skies.

Morning alpenglow lit up Deadhorse Peak above our camp...

…and Big McWaukum Peak off to the north.

We broke camp and started hiking toward Cup Lake, a short distance up valley. The meadows around Larch Lake seemed particularly lush and green.

Above Cup Lake, loose talus slopes ended at a 7360-foot saddle overlooking the huge Glacier Creek cirque.

From Cup Lake Saddle, we could see the long, jagged crest of Big Chiwaukum Peak.

Snowgrass Mountain and Ladies Peak were visible farther to the south. A skiff of fresh snow covered many of the highest pinnacles.

The upper portion of the cirque is a wonderland of glacially polished rock, heather benches, and sparkling tarns. This place cries out for a high camp.

The Chiwaukum schist here exhibits incredibly artistic textures, with convoluted bands of colorful minerals.

We dropped our packs below the cliffs of Big Chiwaukum Peak and headed up with light climbing gear, initially following a left-slanting ramp. This ramp provided an easy Class 1-2 route through the cliffs until just below the ridge crest, at which point we encountered a steep dihedral gully. One roped pitch of very exposed Class 4 climbing got us past the gully and onto the crest.

Easier scrambling on the west side of the ridge brought us below the steep summit pinnacle. Despite the intimidating appearance, there is a reasonable Class 3 route up the pinnacle.

From the summit, we looked down on Grace Lakes, our intended campsite at day’s end. Smooth slopes appeared to provide a direct route down to the lakes, but our backpacks were on the other side of the mountain. Furthermore, one of our goals for this trip was to find a reasonable east-west ridge crossing.

Big Chiwaukum Peak's summit register dates back to 1975 and was placed by the Alpine Roamers from Wenatchee. The register is contained in a venerable aluminum “Roamers tube.” Not many of these are left in the mountains. A party of two had signed in just a few hours ahead of us today (we had seen them on the summit ridge earlier).

A frigid wind and dark skies chased us off the summit sooner than we wanted. We descended via our up-route, retrieved our backpacks, and continued traversing southward. A long, gently sloping snow ramp served nicely as a "white sidewalk" for much of our way down to a prominent rock buttress.

We rounded the buttress, then curved back up to the northwest to gain a 7720-foot saddle closely south of Point 7804. This was the “Snowaukum Pass” that we’d hoped to find between Snowgrass Mountain and Big Chiwaukum Peak. It provides a good east-west route across the main crest. Inviting tundra and talus slopes led readily down to Upper Grace Lake, where we pitched our tent on a gravel bench.

Day 4: Cold fog moved through intermittently all night and into the morning. During a clear period, we scoped out a route up a narrow talus chute ending at a col just north of Point 7955. This chute turned out to be loose and unpleasant, but it effectively got us to 7560-foot “Grace Col” and back over to the eastern side of the crest.

We traversed in a southeasterly direction above Lake Charles until due south of the lake, then we turned right and ascended to a 7480-foot saddle.

The southern side of the saddle has a high, vertical cliff that blocks passage. However, a good ledge system leads off to the west across the top of the cliff. Several cairns and ducks along the way indicated that this is probably a common route to Lake Charles.

Once off the cliff, we began a long traverse over to Ladies Peak at the far side of another large cirque. Despite the distance, a series of heather benches made for enjoyable travel here.

Our traverse route took us above Lake Flora and Lake Brigham, two of the Chiwaukum’s finer gems.

When directly below Ladies Peak, we headed straight up the east face to gain a saddle high on the southeastern ridge. This ridge extends down to Ladies Pass, and a well-traveled climber’s path runs from pass to summit.

From the summit, we could see Lake Mary—our final campsite for the trip—and nearby Lake Margaret. The views were tantalizing, but an icy gale once again chased us off the summit before we were ready.

We descended delightful grassy slopes to the southwest and eventually intersected the hiking trail where it crosses over Mary’s Pass. We hurried down to Lake Mary, arriving scant minutes before dark.

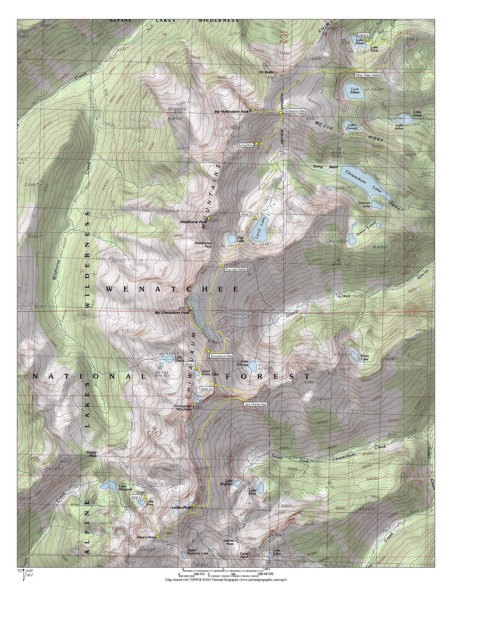

Day 5: It rained steadily for much of the night but stopped just before dawn. We packed up for the last time and hiked over to Frosty Pass, then continued down the Wildhorse Trail. By the time we reached the trailhead and retrieved our mountain bikes, the weather had turned warm and sunny. A 6.5 mile bike ride down to US-2 and back up to the Lake Ethel TH completed our splendid five-day adventure. The map below shows our route, campsites, and summits.

Approximate Total Stats: 28 miles traveled on foot; 12,500 feet gained; 12,100 feet lost.

#Chiwaukum#big mcwaukum#big chiwaukum#ladies peak#larch lake#grace lake#ewing basin#Cascade Mountains

0 notes

Text

Johannesburg Mountain, North Cascades

August 18-20, 2016

Johannesburg Mountain (8200′)

Fred Beckey suggests that Johannesburg Mountain is the most notorious peak in the north-central Cascades. Certainly, its immense north face is one of the most iconic images in the area. I would even say that its visibility from the bustling Cascade Pass Trailhead parking lot makes this the closest thing we have to Switzerland’s infamous Eigerwand. For these reasons—and others—Fay, Matt, Eileen, and I were filled with nervous anticipation when we started up the Cascade Pass Trail on Thursday morning.

We continued up the well-beaten path over Mixup Arm and down to the Cache Glacier. The traditional “easy” route to Johannesburg crosses over Gunsight Notch, which is seen at top-center in the photo below. However, a somewhat more difficult but less circuitous route, called “Doug’s Direct,” has become very popular in recent years. We all decided to give this new route a whirl.

Upon reaching the Cache Glacier’s northern edge, we turned sharply rightward and ascended a broad snow ramp that forms a northwestern-pointing glacial finger. The right-hand corner of this finger leads to a dirty saddle on the skyline.

At the dirty saddle, we turned left and scrambled straight uphill on steep Class 3-4 rock and heather. The steepness and exposure did not favor our heavy backpacks, but we managed to reach a 7300-foot notch in the north ridge of Mixup Peak (6.5 hours from TH) without roping up.

North Mixup Notch provided us with our first view of Johannesburg’s east face. In the glare of late afternoon sun, it looked dark, steep, and foreboding. To make matters worse, it was over 1 mile away and separated from us by a low-plunging ridge. We were obviously in for a long, tedious traverse to camp this evening.

From the notch, we carefully descended a steep heather slope for 700 feet and then made a descending traverse to the ridge buttress. Poor side-hillers will not find this traverse to their liking. Our feet and ankles were tired and sore by the time we crossed under the buttress at 5900 feet.

Beyond the buttress, we ascended talus and scree to a nice heather bench at 6200 feet (8.7 hours from TH). This bench offered small bivy sites and running water but, surprisingly, showed little use by other climbers. We settled in for a two-night stay.

On Friday morning, we were greeted by alpenglow on the east face of Johannesburg Mountain. This face still looked steep and imposing but much more featured and approachable than it had the previous afternoon.

As we ate breakfast, a strange haze gradually drifted in from the east. We surmised that this was smoke from a forest fire somewhere in the eastern Cascades. Overnight, our view of Mt. Formidable, across the valley, went from this…

…to this. It was disappointing to realize that our visibility would be limited by smoke all day.

Starting out at 7:30am, we ascended heather, talus, and snow to Cascade-Johannesburg (C-J) Col approximately 600 feet above our campsite.

From C-J Col, the east face rises over 1000 vertical feet in a series of cliffs and benches. We scoped out a likely looking route, roped up, and started simul-climbing with running belays.

The lower face was fairly steep and exposed in many places but rarely exceeded a difficulty of Class 4.

Although the heather slopes looked benign, they actually felt less secure than the rock steps—and were more difficult to protect. Hopefully, someone will develop an effective “heather anchor” for climbs such as this.

After several hundred feet of zig-zagging up the lower face, we topped out on a rocky shoulder overlooking the Cascade River Valley.

We turned left on the rocky shoulder and climbed over several rock horns. This part of our route involved fun Class 3-4 climbing on solid, grippy rock.

The rocky shoulder merged with the main part of the east face at a point where a red dike ran through an eroded saddle. A small, hanging snow patch continued up from the saddle, and a steep, light-gray gully angled up to the right of the snow patch. Johannesburg’s false summit could be seen towering above the gully.

The light-gray gully extended upward for nearly 500 feet to the false summit. This was the most continuously steep part of the route, but we felt reasonably comfortable scrambling it unroped.

We all reached the false summit in early afternoon (5.8 hours from camp). Our joy at finally achieving this point was immediately doused when we saw how far away the true summit was. It stood 1/4 mile away at the end of a sharp, pinnacled ridge crest. Knowing how long it would take us to traverse over and back, the prospect of a high bivouac started to seem likely.

All available trip reports for Johannesburg Mountain indicated that the summit ridge can be traversed on a series of south-side ledges. We descended 30 feet from the false summit and began working our way across the south face, making use of any visible ledges or ramps. The traversing was never too difficult (mostly Class 2 interspersed with Class 3 moves), but the rock was quite loose and the exposure was relentless.

After 1-1/2 hours of careful scrambling around countless ribs and gullies, we came to a deep slot-gully that marked the base of the highest pinnacle. We roped up for one final pitch of Class 3-4 rock that ended on the summit (7.8 hours from camp). The climb had a momentous feel for all four of us, but it had a special significance for Fay; this summit was #200 in her long quest to climb the 200 highest peaks in Washington. She beamed with a combination of pride and relief while signing the summit register. What a great mountain to cap off her 52-year climbing career!

Johannesburg climbers often remark at how visible the parking lot is from the summit. It was easy to imagine that we were standing atop the Eiger and looking down at a less-civilized version of Kleine Scheidegg. A railroad tunnel through the mountain would have completed the analogy.

We couldn’t afford to fully relax on the summit, knowing what a long descent lay ahead. It started with one rappel down to the slot-gully, followed by a full hour of back-tracking along the exposed ledges.

The sun was low in the western sky by the time we crossed over the false summit and headed down the east face. An abundance of loose rock in all the gullies prompted us to descend in pairs until reaching the rocky shoulder. We made another rappel off the shoulder, scrambled down a heather gully, then made a roped traverse down to the top of the lowest cliff band. One final rappel deposited us on moderately angled slabs directly above above C-J Col. We scrambled down to the col with less than 10 minutes of twilight to spare, then hustled back to camp (5.8 hours from summit) in the dark.

After Friday's long summit climb, we had a leisurely morning on Saturday. Matt headed out of camp around 9:00am so that he could tuck in The Triplets, whereas Fay and Eileen and I didn’t depart until 10:00am. We all regrouped during the painfully long and steep climb back up to North Mixup Notch. We marveled at how heather can grow on a slope this steep!

Following Doug’s Direct route back down to the Cache Glacier involved a down-climb of the Class 3-4 rocky face. With full backpacks, this felt as nerve-wracking as anything we’d descended on Johannesburg. We roped up and used running belays through the worst part. Only upon reaching the glacier could we really relax and savor this grand three-day alpine adventure.