#Flanders Fields memorial

Text

THE PEACE PARK

The Peace Park is a small public park located across from Christchurch Cathedral on the corner of Nicholas Street and Christchurch Place in the Liberties area of Dublin city centre. It was dedicated to Ireland's desire for peace in 1988 during the Trouble

IS A SMALL POCKET PARK ACROSS THE STREET FROM CHRIST CHURCH CATHEDRAL

The Peace Park is a small public park located across from Christchurch Cathedral on the corner of Nicholas Street and Christchurch Place in the Liberties area of Dublin city centre. It was dedicated to Ireland’s desire for peace in 1988 during the Troubles.

The park was designed as a sunken garden, with an aim towards…

View On WordPress

#Artist#Belgium#Christ Church Cathedral#First World War#Flanders Fields memorial#Leo Higgins#memorial#oitering.antisocial behaviour#Patrick Kavanagh#Peace Park#rainwater#Seamus Heaney#soil from Flanders#Tree Of Life#unken garden#W.B.Yeats

0 notes

Photo

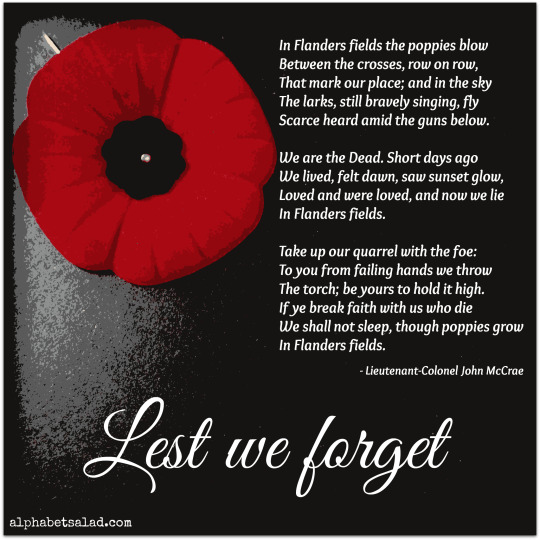

Remembrance Day

Remembrance Day (sometimes known informally as Poppy Day) is a memorial day observed in Commonwealth of Nations member states since the end of the First World War to remember the members of their armed forces who have died in the line of duty. Following a tradition inaugurated by King George V in 1919, the day is also marked by war remembrances in many non-Commonwealth countries. Remembrance Day is observed on 11 November in most countries to recall the end of hostilities of World War I on that date in 1918. Hostilities formally ended “at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month”, in accordance with the armistice signed by representatives of Germany and the Entente between 5:12 and 5:20 that morning. (“At the 11th hour” refers to the passing of the 11th hour, or 11:00 am.) The First World War officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919.

The memorial evolved out of Armistice Day, which continues to be marked on the same date. The initial Armistice Day was observed at Buckingham Palace, commencing with King George V hosting a “Banquet in Honour of the President of the French Republic” during the evening hours of 10 November 1919. The first official Armistice Day was subsequently held on the grounds of Buckingham Palace the following morning.

The red remembrance poppy has become a familiar emblem of Remembrance Day due to the poem “In Flanders Fields” written by Canadian physician Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae. After reading the poem, Moina Michael, a professor at the University of Georgia, wrote the poem, “We Shall Keep the Faith,” and swore to wear a red poppy on the anniversary. The custom spread to Europe and the countries of the British Empire and Commonwealth within three years. Madame Anne E. Guerin tirelessly promoted the practice in Europe and the British Empire. In the UK Major George Howson fostered the cause with the support of General Haig. Poppies were worn for the first time at the 1921 anniversary ceremony. At first real poppies were worn. These poppies bloomed across some of the worst battlefields of Flanders in World War I; their brilliant red colour became a symbol for the blood spilled in the war.

Source

#In Flanders Fields by Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae#poppy#Canada#USA#Remembrance Day#Community Veterans Memorial#Munster#Indiana#Sequim#Purple Haze Organic Lavender Farm#Sweden#wildflower#travel#Ontario Veterans Memorial#National War Memorial by Vernon March#Ottawa#Toronto#Ontario#Trois-Rivières#Québec#Monument to the Brave by Cœur-de-Lion McCarthy#11 November#Allan Harding MacKay#11 November 1918

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembrance Day: Honouring the Sacrifice and Resilience of Heroes

Shaina Tranquilino

November 11, 2023

As we approach November 11th, our hearts collectively turn to pay tribute to those who have made the ultimate sacrifice in service to their country. Remembrance Day is an occasion that allows us to reflect upon the valour, resilience, and unwavering spirit exhibited by countless heroes throughout history. On this solemn day, let us come together as a nation to remember these extraordinary men and women and express our gratitude for their immeasurable contributions.

1. A Historical Perspective:

Remembrance Day holds its roots in the armistice signed between Germany and Allied forces on November 11, 1918, effectively ending World War I. Originally known as Armistice Day, it was officially renamed Remembrance Day after World War II to honour all military personnel who lost their lives in conflicts worldwide.

2. Symbolism and Traditions:

The red poppy flower has become synonymous with Remembrance Day due to Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae's poignant poem "In Flanders Fields." Wearing a poppy serves as a powerful symbol of remembrance and solidarity with those who served or continue to serve.

Additionally, two minutes of silence at 11 a.m. on November 11th mark the moment when hostilities ceased during World War I – a time for collective reflection and respect for fallen heroes.

3. Paying Tribute: The Importance of Remembering:

Remembrance Day is not just about honouring past sacrifices; it is also an opportunity for us to acknowledge the ongoing dedication of servicemen and women around the world. Their commitment ensures our safety, freedom, and peace while reminding us of the cost involved.

By actively engaging in remembrance ceremonies, visiting war memorials, or even participating virtually through various initiatives, we can demonstrate our gratitude towards those who selflessly put themselves in harm's way.

4. Teaching Future Generations:

As time passes, it becomes even more crucial to educate younger generations about the significance of Remembrance Day. The sacrifices made by our predecessors should not fade into oblivion but instead serve as a reminder of the importance of peace, unity, and global cooperation.

Through educational programs, storytelling, or visiting historical sites, we can instill in children an understanding of the price paid for the freedom they enjoy today – nurturing empathy and fostering appreciation for those who served.

5. Beyond Borders: A Global Perspective:

Remembrance Day is observed worldwide, extending beyond national boundaries. It serves as a unifying force that transcends language, culture, and politics. Regardless of where we are from or what conflicts have shaped our countries' histories, honouring fallen heroes reminds us of our common humanity and shared responsibility to strive for lasting peace.

Remembrance Day stands as a poignant reminder of the bravery displayed by countless soldiers and civilians throughout history. This solemn occasion allows us to honour their sacrifice while acknowledging the ongoing efforts towards building a world free from conflict. By participating in remembrance ceremonies and teaching future generations about the importance of gratitude and perseverance, we ensure that their stories live on forever.

So this November 11th, let us stand united in silence and reflection, remembering with utmost reverence those who fought valiantly for a brighter future – inspiring us all to be better stewards of peace.

#Remembrance Day#November 11#Red poppy#Lest We Forget#Never Forget#Honouring Heroes#Remembering the Fallen#War Memorial#Peace and unity#Veterans#In Flanders Fields

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

man paul fussell is so mad at that stupid Flanders Fields poem and he is so right and can keep on saying it louder for the people in the back

#in flanders fields#tagging my hate#not actually rereading Great War and Modern Memory but conversation at dinner sort of worked its way around here via monkey's paws#wwi#paul fussell

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Windows 10 search bar today:

SABATON - In Flanders Fields (Official Lyric Video) - YouTube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Text

everyone has a weird, impractical skill that they never get to show or bring up to anyone. reblog and tell me about yours!

#tag game#in the tags#mine is being able to recite ‘in flanders fields’ from memory >5 years after I last read it

1 note

·

View note

Text

Memorial Day 2022

Memorial Day is an American holiday on which those who died in active military service are remembered. It’s a day for honoring and mourning people who’ve died while fighting to keep us safe. It’s a time many visit friends and family who have made the ultimate sacrifice.

Originally known as Decoration Day, it originated in the years following the Civil War and became an official federal holiday…

View On WordPress

#active military service#American holiday#beautiful#beauty#beauty blog#beauty blogger#beautyblog#health#In Flanders Fields#Lifestyle#looking joli good#lookingjoligood#makeup#memorial#memorial day

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Guildsman Goes Forth to War, World-Building Part II

Historical Departures:

As you might imagine, in a world that's experienced quite a significant change almost a thousand years previously, Europe circa 1500 AD in A Guildsman Goes Forth to War is not the same as the one from our timeline. Names and places are familiar but distinct, and the borders of entire countries have shifted because a battle that went one way in one timeline went the other in this.

For the purposes of this novel, I wish to draw your attention to two more significant historical departures that will be the most central to the main characters and the plot.

The first departure has to do with the outcome of the Franco-Flemish War at the beginning of the 14th century. As in our timeline, the war began as a conflict between Phillip the Fair (although in this world, he was King of Gallia, rather than of France) and the Count of Flanders, and turned into a Flemish revolt against the overlordship of France that enraged and terrified the French chivalry after the Guldensporenslag. Unlike our timeline, however, the Count of Flanders offered marriage of his younger daughter to Rudolf I of the Empire after Phillip blocked his marriage alliance to Edward of Anglia.

While sadly in this timeline the Flemish cause did not ultimately win victory either, the Imperial marriage meant that when French forces pushed the Flemings' backs to the wall at Zierikzee and Mons-en-Pévèle, they were met by an Imperial expeditionary force. Rudolf I was no partisan of the burghers, but neither was he about to have Phillip the Fair as a neighbor. And so instead, the Low Countries became a buffer zone between the Kingdom of Gallia and the Sacrum Imperium.

Major warfare between Gallia and the Empire was avoided. (After all, Phillip had his hands full with Edward and Rudolf desperately needed that bastard Pope to agree to his coronation.) As for the people who had fought so hard for their freedom, the militias were disbanded, the burghers were stripped of much of their former independence, all commoners were forbidden to carry arms, and the local nobility were carefully balanced between Gallician and Imperial lines to keep the peace. Everyone returned to the business of spinning thread into gold. But still the memory of the goedendag lingered...

The second, more recent event is the rise of the Lega di Mille Communi. At the height of the Wars of the Guelphs and Ghibellines, a number of Italian communes hatched a conspiracy "as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man." To end the constant fighting and free themselves from the ambitions of Pope and Emperor both, these communes pretended loyalty to both factions, offering loans and fighting men while working within the walls of their own cities to plant spies, provacateurs, and assassins among the leading families of the signorile.

This silent campaign built to its height at the Second Battle of Legnano, where the combined forces of Pope Boniface VIII and his Guelph allies and Emperor Louis IV and his Ghibellines met again at that place honored in song and memory as the place where Barbarossa was humbled. When the battle was fully joined, a pre-arranged signal was given and the condottieri on both sides turned on their own armies, making a daring charge for the command tents of Pope and Emperor alike. In the confusion and chaos, those great and noble persons were taken captive in the name of the newly revealed Lega di Mille Communi.

The shockwave echoed across all Europe. For six months, the greatest secular and religious authorities in Christendom lingered in golden fetters, while Kings and Cardinals from ultramontano threatened foreign intervention. Across northern and central Italy, a civil war raged in the streets and in the fields, but the Guelph and Ghibelline partisans found themselves leaderless and undirected, unwilling to combine with their hated enemies against the professional forces of the well-heeled Lega who toppled government after government from within and without. When the dust had settled, a "Treaty of Perpetual Liberty" was signed by the Empire and the Papal See alike. Under the terms of this pact, the Lega was recognized as independent of both, the sole legitimate sovereign of all territories south of the Alps.

Naturally, this document signed under heavy coercion was immediately repudiated the moment the principals were freed (albeit under heavy bond). Louis IV declared war the moment he set foot on German soil, and Boniface would have done the same in his own territories had he not dropped dead of a rage-induced stroke. For another ten years, the Lega fought to uphold the Treaty, and ultimately narrowly triumphed thanks to a crucial alliance with the Swiss Confederacy that bled the Emperor's legions white as they tried to fight their way south through the Alps, and thanks to a deadlocked Papal conclave (kept that way by heavy bribery and constant espionage) that allowed the Lega to fight on one front at a time.

But in the end, the Lega endured because of the simple principles of its constitution. Under the articles of federation and defensive alliance, each commune was largely free to govern itself within certain boundaries. No separate alliance or agreement with any foreign state was allowed. Limited wars between Communi were allowed after arbitration, but not to the point of outright conquest of one city-state over another. Contracts would be honored across the Lega, and exchange rates between local currencies would be fixed at yearly conferences. Violators would face the combined forces of every other Communi bound together in fraternal oath.

One Pope after the other was crippled with debt until they had to sell the Donation of Pepin city by city and valley by valley, culminating in a truly Croesian subvention from the Lega for the new Prince of the Vatican. The Kingdom of Naples tried again and again to fight its way up the boot, only to find itself mired in costly sieges ahead and suspiciously well-funded peasant rebellions behind, until eventually the House of Anjou declined into civil war. The Lega was not a peaceful country after independence, but the fighting kept their condottieri well-trained and well-paid, and a new cultural ethos emerged among the Communi that they would uphold as jealously as the virginity of their kinswomen: "I against my brother, my brother and I against my cousin, my cousins and I against a foreigner."

And so for the first time since the time of the Divine Julius, one of the major powers of Europe was a Republic(s). A specter had begun to haunt the crowned heads of Christendom...

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The war would be over by Christmas. That was what everyone said, when Britain, France, and Germany went to war in August 1914. Maybe that’s why, by the start of December, with no victory in sight, there was a pause in the fighting along parts of the Western Front stretching from Belgium through France. And maybe that’s why, when singing broke out in the trenches on Christmas Eve, soldiers on both sides decided to risk a walk up into no man’s land and even, in one recorded case, a soccer kickabout. Troops on both sides sang “Silent Night” as snow began to fall.

The truce was never formally declared by any power. Although Pope Benedict XV had called for a cease-fire earlier in the month, it had been rejected by all parties. France and Belgium had little appetite for a truce with an invading army. And in a war between global, multiethnic empires, there was little agreement about the timing or the meaning of a Christmas truce for soldiers who were Muslim, Sikh, Jewish, Hindu, or Shinto. Even for Eastern Orthodox troops on the Eastern Front, Christmas would be a few weeks later.

Instead, there were spontaneous truces along the front lines. While both sides engaged in singing, many Germans had reportedly decided not to take any action from Dec. 25 to 27. In France, near Laventie, German soldiers started putting up Christmas trees along their trenches on the 23rd and their officers requested a meeting with their British counterparts. In their book, Christmas Truce, Malcolm Brown and Shirley Seaton report that the German officers “proposed a private truce for Christmas Eve and Christmas Day” that the British officers accepted. Similar informal arrangements were made up and down the front lines, with different results in different sectors.

The informal nature of the truce meant that not everyone participated. This is partly why the truce has now attained a mythical quality—many who were on the front did not experience it and so doubted that it had taken place. Even where peace seemed to prevail, officers worried that “the truce will probably go on until someone is foolish enough to let off his rifle.”

Across the Western Front, the Christmas truces came to an end at different points. By the 27th, rain had resumed and the soldiers were once again knee-deep in mud. Along some parts of the line, fighting resumed in January. But one soldier wrote home that part of the front near Ploegsteert in Flanders didn’t really see any action from the Christmas Truce until mid-March. The Battle of Neuve Chapelle in March 1915 definitively shattered the peace. Attempts for an Easter truce in early April were largely ignored.

The Christmas Truce that took place in the first December of World War I has transcended historical curiosity to become a feature of popular memory. Pop songs, TV shows, and even ads have all made reference to the events of December 1914. Why has it adhered in this way? What has it come to symbolize, more than 100 years on?

Regular truces were a typical part of pre-modern warfare. Staged battles left time for clearing the field, burying the dead, and regrouping. Informal encounters between soldiers did not always lead to fighting, and impromptu Christmas truces occurred in the U.S. Civil War and the South African War in 1899. In a way, the Christmas Truce appeals because it seems to point to the last moment of an older form of warfare. Given the horrors of the war to come, it seems poignant in its innocence.

The popularity of the Christmas Truce of 1914—even though it was not repeated for the rest of World War I—was not just as a token of nostalgia, though. It was also responsible for creating something new: the idea that there should be a Christmas truce.

One of the enduring legacies of World War I was the shift from an approach to humanitarian principles and human rights that was “episodic, empathic, and voluntary” to, as one scholar put it, a “permanent, professionalized, and bureaucratic” responsibility of states operating in a transnational network. Alongside these developments in humanitarian organizing, truces moved out of the realm of improvised, informal agreements between soldiers. Instead, they were called for and negotiated by states and transnational peace organizations. And they did so with the Christmas Truce of 1914 as a model.

For instance, in 1965, in the midst of the escalating Vietnam War, the Viet Cong proposed a Christmas cease-fire. Meant to parallel the cease-fire that had accompanied the Vietnamese Lunar New Year celebrations earlier in the year, it was embraced back at home and internationally by the peace movement. The truce was arranged with some skepticism on the ground. Even more so given the previous year’s Christmas Eve bombing of a hotel where many U.S. officers were staying. The truce was agreed to and formally communicated to both sides.

A newspaper report from the cease-fire explicitly echoed the coverage of the 1914 truce. “It was quiet—the guns of war were stilled by a Christmas truce for the first time in almost a year,” the paper reported. “And from the top of the hill, the words of ‘silent Night’ wafted down” as the men rested their rifles on their foxholes and contemplated what the Viet Cong forces made of the song.

At the end of the 48-hour pause, both sides accused each other of violating the cease-fire. Radio Hanoi reported that “in complete disregard for their proclaimed Christmas truce, the U.S. imperialists Sunday sent many flights of aircraft.” The U.S. argued that these were reconnaissance flights, rather than bombing raids, and that the “Communists had launched at lease 60 small attacks.”

What the soldiers of World War I accidentally stumbled on was a new form of propaganda. Christmas cease-fires build morale among the troops, but also more widely. A key feature in the rhetoric of war is convincing your side that the opposing side is not just wrong, but bad. Truces and cease-fires play into this: The side proposing the cease-fire paints itself as humane. Violations of the cease-fire are fodder for arguments that the violators are inhumane.

In foreign policy, the Christmas Truce endured because it turned out to be good for both international and domestic public relations. But as a result of this realization, Christmas cease-fires also became more top-down. While the soldiers were responsible for organizing spontaneous truces along the front lines in 1914, the Christmas truces of the Vietnam War and other more recent conflicts have been ordered by leaders, often in response to international pressure. In Vietnam, despite suspicion among U.S. troops that the Viet Cong “took advantage of the truce” to rearm and resupply its forces in the south, the Christmas truce was often implemented. While this provided respite and a chance for point-scoring in the media, some U.S. soldiers were left asking, “What good would it do?”

And they asked that with good reason. Christmas—and other religious holidays—have been just as likely to mark the beginning of a campaign, taking advantage of the enemy’s hope for some respite. George Washington crossed the Delaware River on Christmas 1776, surprising the British-allied Hessian troops in Trenton. During the Tet Offensive in the Vietnam War, the Viet Cong took advantage of the Lunar New Year in 1968 to attack while many of South Vietnam’s soldiers were on holiday leave. And then-U.S. President Richard Nixon broke the expected Christmas Truce tradition in 1972 when the U.S. launched its largest B-52 raid on North Vietnam in the course of the war. The Yom Kippur War in Israel began on the Jewish holiday in 1973. Operation Ramadan in the Iran-Iraq War launched to coincide with the holy month in 1982.

This explains the unease of the leadership in December 1914. In Laventie, one group of British soldiers was about to withdraw from the trenches on the 26th when a German deserter, taking advantage of the truce, crossed to warn them that an attack was imminent. The British soldiers fired artillery at the German trenches and then lay in wait for the attack. But it never came. And the Germans, put on alert by the artillery fire, similarly had spent the night in anticipation of a British attack.

In fact, while the 1914 Christmas Truce saw soldiers sharing tobacco and wine, Christmas puddings and songs at scattered locations along the trenches in Belgium and France, the Germans dropped their first aerial bomb on Britain, at Dover on Christmas Eve. On Christmas Day, the British used seaplanes to attack the Imperial German Navy, stationed in the harbor of Cuxhaven.

The 1914 Christmas Truce in particular has been read in popular culture as a moment when soldiers rejected their officers’ orders and rejected the nationalist propaganda that they had been exposed to, which demonized their opponents. The Christmas Truce appeals to the idea that ordinary people would get along if only they weren’t ordered to fight each other by their governments. In 1914, soldiers ignored officers and took risks to make human connections with people they were supposed to hate.

Christmas truces have subsequently become a regular prop in international diplomacy. In conflicts ranging from the Philippines to Colombia, Sudan to Ukraine, it’s hard not to see the Christmas Truce as having retained its mythical status precisely because of its usefulness as propaganda. Perhaps it would be better to remember the Christmas Truce as one poem concluded in January 1915: “God speed the time when every day/Shall be as Christmas Day!”

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

poppies

In Flanders Fields the poppies grow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

In Flanders Fields by John McCrae

I have always found the excerpt above, and the rest of the poem that comes after it to be pleasant to the ear, sweetly melancholic and, to be honest, more than a little creepy once you hit the threat at the end. The mental image of mostly desiccated World War I soldiers clawing their way out of the upturned soil, spilling flecks of half rotted uniform and red flowers from their bodies as they drag themselves forward after me just because I don't feel like holding a grudge against another country for a war nobody really should have been in in the first place isn't exactly what I suspect Lt. Col. McCrae was going for but its sure the picture he painted in my mind. Not cool, John. Not cool.

In other news, the poem did help make the poppy a popular symbol for war veterans that died in battle, especially overseas. These days red paper poppies are worn in jacket lapels and sold on street corners in multiple Western countries during Remembrance Day, Anzac Day and Memorial Day. Today that's pretty much the only association most of us have with the flowers but for the soldiers that lived during that time, the red corn poppies were a familiar sight, being some of the first and hardiest plants to grow in the churned up soil around trenches, the morass of no-mans-land between and yes, the freshly dug graves that grew almost as quickly as the poppies themselves across the battlefields.

Poppies were associated with the dead long before WWI however.

Hey, August babies! Let's talk about one of your birth month flowers (and keeping corpses in their graves)!

Did you know that poppies have been found in graves and carved on tombstones all the way back to Roman times? The Greeks and the Romans associated the poppy with forgetfulness and sleep. Giving the dead poppies was supposed to help them sleep in peace, though I did see one article speculating that the poppy seeds found in some graves was more akin to the old legend that the undead have obsessive-compulsive disorder and will be compelled to stop whatever they are doing to count scattered small items like seeds.

GIF by gifs-of-puppets

Who knew Sesame Street was so in touch with its darker side?

Back to the point, the Greek gods Hypnos (sleep), Thanatos (death), Nyx (night) and Morpheus (dreams) all have poppies as their flowers. Pappa means 'milk' in latin and the milky sap as well as the seeds of poppies have been used since ancient times to grant forgetfulness, peace and sleep, tracing as far back as the early Egyptian empires. Multiple opioids are made from the poppy with some of the most famous being opium, heroin, codeine and morphine, named after Morpheus for its dreamlike effect on the human brain and body. The opioid crisis has been with us since at least Victorian times and for many of the same modern reasons back then as well.

Speaking of escape from pain, Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, is associated with poppies as well. It was said that after Persephone was kidnapped by Hades, Demeter was so distraught that the gods gave her poppy seeds to help her sleep and escape her grief for a time. Afterward, the flower would spring up wherever her footsteps fell. The ancient Assyrians also associated poppies with agriculture and in fact, even today, poppies seen growing in cornfields are considered lucky and a sign of a good harvest to come.

Poppies in China are also considered lucky, or at least the smell of them is and they are a melancholic symbol between lovers too. The story I read claims that the poppies growing on his lover's grave gave a Chinese hero the inspiration he needed in battle.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz employed a poppy field to put its heroes to sleep.

Poppies should only ever be given in bouquet of thirteen. Any other number of poppies is considered unlucky.

Greek athletes would mix poppy seeds, wine and honey for an invigoration drink.

In Wales, sleeping with poppy seeds under your pillow will show you the face of your future lover or give you the answer to whatever question you were thinking of when you fell asleep. The seeds are a ward against forgetfulness.

#poppy#poppies#august#Demeter#morpheus#folklore#superstition#herbalism#cottagecore#birth flower#birth month#wizard of oz#vampire#flanders fields#anzac day#remembrance day

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

John McCrae wrote the poem “In Flanders Fields” on May 3, 1915.

#John McCrae#wrote#poem#In Flanders Fields#3 May 1915#anniversary#Canadian history#Sweden#wildflowers#meadow#flora#Washington#USA#Purple Haze Organic Lavender Farm#Community Veterans Memorial#Munster#Indiana#Trois-Rivières#Québec#Canada#World War 1 Monument#Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae#WWI#World War One#Monument to the Brave by Cœur-de-Lion McCarthy#poppy#Papaveroideae#Ontario Veterans War Memorial#Allan Harding MacKay

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The untouched bedroom of World War I soldier Hubert Rochereau. He died in an English field ambulance on April 26, 1918 a day after being wounded during fighting for the village of Loker in Flanders. He was 21 years old. His parents had no idea where he was buried until 1922 when his body was discovered in a British cemetery and repatriated to the graveyard at Bélâbre, France. They turned the room into a permanent memorial, leaving it largely as it had been the day he went off to war.

— BBC World News

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the eleventh hour on the eleventh day of the eleventh month – we will Remember Them.

The red poppy is a symbol of both Remembrance and hope for a peaceful future.

During WW1, much of the fighting took place in Western Europe. The countryside was blasted, bombed and fought over repeatedly. Previously beautiful landscapes turned to mud; bleak and barren scenes where little or nothing could grow.

There was a notable and striking exception to the bleakness - the bright red Flanders poppies. These resilient flowers flourished in the middle of so much chaos and destruction, growing in the thousands upon thousands.

Shortly after losing a friend in Ypres, a Canadian doctor, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae was moved by the sight of these poppies and that inspiration led him to write the now famous poem 'In Flanders Fields'.

The poem then inspired an American academic named Moina Michael to adopt the poppy in memory of those who had fallen in the war. She campaigned to get it adopted as an official symbol of Remembrance across the United States and worked with others who were trying to do the same in Canada, Australia, and the UK.

Also involved with those efforts was a French woman, Anna Guérin who was in the UK in 1921 where she planned to sell the poppies in London.

There she met Earl Haig who was persuaded to adopt the poppy as our emblem in the UK. The Royal British Legion, which had been formed in 1921, ordered nine million poppies and sold them on 11 November that year.

The poppies sold out almost immediately. That first 'Poppy Appeal' raised over £106,000 to help veterans with housing and jobs; a considerable sum at the time.

In view of how quickly the poppies had sold and wanting to ensure plenty of poppies for the next appeal, Major George Howson set up the Poppy Factory to employ disabled ex-servicemen.

The demand for poppies in England continued unabated and was so high, in fact, that few poppies actually managed to reach Scotland. To address this and meet growing demand, Earl Haig's wife Dorothy established the 'Lady Haig Poppy Factory' in Edinburgh in 1926 to produce poppies exclusively for Scotland.

Today, over five million Scottish poppies (which have four petals and no leaf unlike poppies in the rest of the UK) are still made by hand by disabled ex-Servicemen at Lady Haig's Poppy Factory each year.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

this is going to be soooo oddly specific but uhm. do you mind if i ask what poems you had to read? i have this distinct memory of a poem about a soldier and a field and some such, but i can't remember anything beyond that and i've never been able to find it again... also poetry is so real always and i needf to read more

eek i can list some of them off a lot of them are field poems… in flanders fields is the one that comes to mind first, the hollow men (also eliot), OH it definitely could have been on returning to the front after leave by alan seeger that is a frequently occurring one though it was not an in class reading… we read the owl by edward thomas in class and i did not like that one…!!! if you are looking for like. war poem recommendations generally i like ae housman because he doesn’t only write war poems he writes other stuff too… um. what else. oh dulce et decorum est that one is always good…. siegfried sassoon has some good ones but they are. dark in comparison to some of the other ones on here… if you want more i could probably give you more… honorary mention to the charge of the light brigade which is not a ww1 poem it’s a war of 1812 poem but. i still like it…

8 notes

·

View notes