#George Ticknor

Text

Anna Cora Mowatt, Mimic Life, and the Critics

Anna Cora Mowatt, Mimic Life, and the Critics

Part III: Publication

Although January of 1856 is usually listed as the publication date of Mimic Life, newspaper ads and reviews indicate that there was an initial release of the book starting in the Northeast around December 25, 1855. This run quickly sold out, leading to the publication of blind items similar to this one that appeared in the Charlotte Democrat in the early weeks of January,…

View On WordPress

#anna cora mowatt#Autobiography of an Actress#Boston Evening Transcript#charles dickens#Charlotte Cushman#edgar allan poe#epes sargent#George Ticknor#James T. Fields#John Rueben Thompson#knor#Mimic Life#shakespeare#Stella#The Lady Actress#The Prompter&039;s Daughter#The Unknown Tragedian#theatrical autobiography#Ticknor and Fields#Victorian Actress#Victorian Literature#Victorian theater#victorian theatre#William Foushee Ritchie

1 note

·

View note

Photo

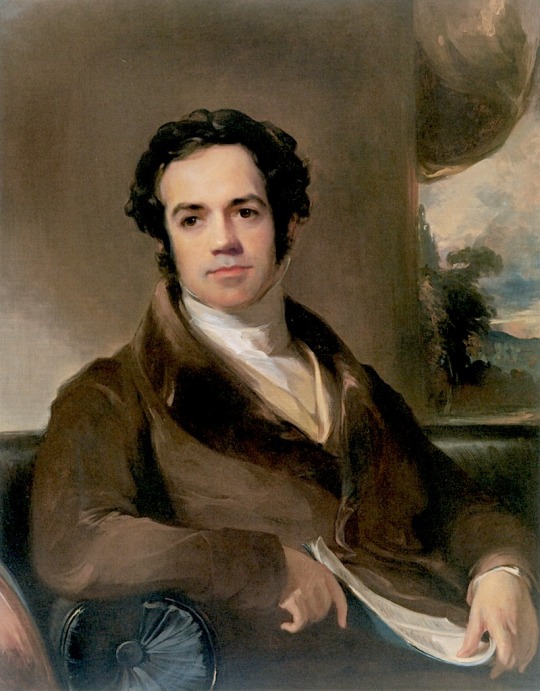

George Ticknor, 1831, Thomas Sully

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 Days of La Fayette - Day 9

From La Fayette to Thomas Jefferson during his Farwell-Tour

[Washington December 9th 24]

The Happy days I Have past at Monticello Are over; But they Have Left on My Heart an impression Never to Be efaced; I Rejoice at the Visit You are Going to Receive, not only Because it will Be pleasing to You, But on Account of the General Good it May produce; You will, No doubt, talk with Mr Webster of Your ideas to facilitate the Emigration of Coloured people, and, Connected with it, their enfranchisement, of His own wishes, expressed in Congress last year, With Respect to the Greeks; the Appropriation of Money, which He Had proposed, in Case it was thought fit to send Agents to that Republican Confederacy, Has Nothing Contrary to the system and precedent of American policy; I Have seen with pleasure the insistance of the president’s Message on the Maintenance of Republican Confederate Constitutions in South America as from a late Conversation with the Brazilian Minister I Could, entre nous sois dis, trace a settled plan and Great Hopes to saddle this Hemisphere With the two principles of Monarchy and Aristocracy, so far as Respects the New Emancipated States.

Mr ticknor Carries to You the flourens’s Work, a Small book Respecting the Jesuits, and the prospectus of the New french encyclopedia; I Am very Happy to Hear Your professors are Arrived or daily Arrived. You will know the New Marks of kindness with Which I am Honored; as to the other object which of course I must Remain stranger to, I Have Reasons to Believe it will Be a Matter of previous Conferences.

present My Affectionate Respects to Mrs Randolph, the Ladies, and Assure them, as well as the Gentlemen of the Cordial Affection that Binds me to them. There is a subject very delicate to be Mentioned; Yet, if what is told me Be true, I cannot Refrain from telling to You if Not Yet to His, that for Her, and With You I Most paternally feel on the supposed occasion Adieu, My dear friend, I am as I Have long been and shall be to my last Breath

Your Most Affectionate friend

Lafayette

The Members from North and South Carolina, and at the Head of them the excellent Mr Braton Have not only Assented to, but Advised My postponing the Southern Visit to the Oppening of the Spring, When I may Go from Georgia to Neworleans and Up the River to the Western States. George and le ballew desire their Most Grateful Respects.

#24 days of la fayette#lafayette#la fayette#letter#thomas jefferson#handwriting#marquis de lafayette#1824#library of congress#founders online#farewell tour#triumphant tour#tour of 1824-1825

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"One evening in September, 1827, David rode out to Watertown on his trusty steed Thalaba. Because her family, like her friends, disapproved of the young lawyer as a husband, Maria met him at the Curtises'. Twelve-year-old George Ticknor Curtis spied on their interview through the staircase banister and he told later that David had looked frozen with fright as he proposed at last. The lover's face tautened as Maria answered neither yes nor no, but as long as she did not laugh at him there was hope. For four hours, while that child on the stairs never missed a word, David pleaded his cause, and four times he left her to go outside to pacify his tethered horse. George probably exaggerated to make a good story better, yet David too may have been uncertain that marriage was right for him. The horse made a convenient excuse to escape, but something, those dark eyes of the girl on the horsehair sofa, drew him right back. At any rate, at one in the morning he melted her resistance and she agreed to become his wife.

The engagement announcement shook the family. Her sisters-in-law bobbed their heads and brother James's wife, old shrew that she was, murmured, "Through the wood, through the wood, and find a crooked stick at last." All of them fussed at her for choosing this drifter instead of a man more settled in a profession. They condemned him for being a visionary even while they admitted his charm, and they enraged Maria by quoting something that an outsider had told them, that David's sense of business was about equal to "cutting stones with a razor." His efficiency in defending any derelict with no money for lawyer's fees did not impress them, and they warned little sister that he would never notice if his own or her boots went without cobbling. Not that David was ever unkempt. He looked tall and distinguished in his shabbiest clothes; and his pallor wrung, while his smile won, ladies' hearts. Maria simply blew their criticisms away and relied on her Swedenborgian theories which had taught her to look for a man who, like her, believed that to live without charity was to exist without love.

Moreover, she was sure to be practical enough for both of them. Swedenborg showed her that David's idealism was not a flaw but a sign of near perfection, and she preferred her knight as he was, quite without armor. She gave David a copy of The Rebels as an engagement present. They planned a small wedding and invited only the near and dear, but Maria was sad because Mary Preston and her family could not come down for it from Norridgewock. Maria had to pour out all her bridal rhapsody by mail. She told her sister about gifts and plans and clothes. My mantua maker has been here a week. I have a claretcolored pelisse lined with straw-colored silk made in the extent of the mode to make anyone stare, one black-figured levantine silk and one swiss muslin. Riches indeed for a girl whose taste verged on the simplicity of a Quaker. They were married in Watertown at eight o'clock in the evening on Sunday, October 19, 1828.

The bridegroom's dark coat accentuated his pallor, but the bride, gowned in India muslin with scrolls of white satin, was as lovely as could be. Her eyes were luminous and her mouth soft as she promised to love, honor, and obey. She looked directly at David as she made her vows and was sure that they were joined for a lifetime of truth, good, and bliss; and David saw that she was beautiful. The wedding guests toasted the bride with wine and nibbled at the thirty-five pounds of cake Maria had ordered from the baker. Festivities over, the Childs drove to a tiny house in Harvard Street, no more than a mile from the heart of Boston and quite near David's office. The bride wrote to her sister that the house was "a proper little martin-box, furnished with very plain gentility." Maria's simple taste was part home training and part caution which stemmed from her awareness that budgets and David were poles apart.

Her foresight was soon confirmed, for most of David's erratic income as lawyer, legislator, and journalist (he became editor of the Massachusetts Whig Journal during that year) was gone before she saw it. What he earned, he loaned or gave away outright. Maria did not really mind. She was earning enough for both of them and she realized that he did only what he had to do. She put a few dollars aside for the future without comment and saw to it that their home was as gracious and welcoming as it could be. What fun to polish and fuss over her own home, to display her wedding gifts, to hang prisms in the window, and have a kitten on the hearth! Beautiful Emily Marshall, a legendary New England beauty, had sent stellar lamps with pretty etched globes which shone as brightly as Emily herself among ordinary girls. One of the lamps stood in the center of the writing table so that Maria could share its light with David as he wrote editorials for the Whig party.

David was enraged at the election of Andrew Jackson to the Presidency in 1828. Jackson stood for all that he, as a rabid Whig, detested—a man violent, arrogant, impatient of schooling and careless in his selection of officeholders. He seemed to be against the banking interests of the East and certainly unsympathetic to Henry Clay's favored internal improvements at national expense. It was Jackson who first made Maria concentrate on politics and the personalities behind them. In a sense it was this cognizance of Jackson that began a redirection of her life. David wrote to Henry Clay on the 14th November, asking for an explanation of Jackson's election. David was aware that his fellow New Englander, defeated President John Quincy Adams, was an austere, tactless character, devoted to his country but with no flair for winning public favor. Henry Clay, Adams' Secretary of State and one of the most astute politicians America ever had, had been unable to improve Adams' image as a candidate no matter how he tried.

…Usually it was restful to write with David beside her in their "martin-box" house. She looked around again. What a nice place this home of theirs was. No matter how stormy the future, she and David would keep their home and sanctuary. The things they had been given as wedding gifts would give it flavor and permanency, the plated candlesticks and a snuffer on a tray on the mantelpiece, and the butter knife and cream ladle with which she set the table even if no butter or cream were on the menu. She said that these pretties gave an air to the room. Other friends had sent more practical if less durable gifts: a keg of tongues from Mrs. White, whose daughter would one day marry James Russell Lowell; and a jar of pickles from the Thaxters. The prisms in the window flashed rainbow colors over the drab walls, the kitten purred, and Maria was sure that life could not have been better. And so it would have been if David's openhandedness had not driven them into debt.

Instead of putting Maria's small savings out at a decent rate of interest, those went first to cover his promises of help to a complete stranger whose notes that David had no right to sign in the first place; but Maria's savings not being enough, they had to borrow five hundred dollars from Mr. Francis to cover the rest. All this only seven months after the wedding, and how the sisters-in-law must have chortled. Maria would be headstrong and marry, would she? Maria herself was humiliated by the loan from her father and the realization that the family predictions had been only too true, but she refused to let the money poison her relationship with her husband. He was wonderful, endlessly wise in ways she knew nothing about, and witty, and she would not permit any speculation that theirs was less than a perfect marriage. It was during this first year that she wrote the Frugal Housewife for "those who are not ashamed of economy."

Her own tribulations undoubtedly gave the book its authenticity. Its unvarnished, homely style flavored its recipes, and its hints, "odd scraps for the economical," helped to extend any budget. Experienced housewives nodded approvingly at this: "A little salt sprinkled in the starch while it is boiling tends to prevent it from sticking; it is likewise good to stir it with a clean spermaceti candle." And at this: "Pepper, red cedar chips, tobacco, indeed almost any strong spicy smell is good to keep moths out of your chests and drawers but nothing is so good as camphor." And how did a new bride know this except by having looked into someone else's kitchen? "Always have plenty of dish water and have it hot. There is no need to ask the character of a domestic if you have ever seen her wash dishes in a little greasy water."

This could have been a private hit against those carping sisters-in-law who did employ domestics. Certainly Maria had none in her "martin-box." There were numberless cookbooks and household manuals on the market but the Frugal Housewife caught the public fancy. It was read in fashionable boudoirs, in farm kitchens, and in the trademan's cottage; and any country girl who came to town to buy a length of silk for her wedding gown was likely to bring back the Housewife as well. When Maria pronounced that preserves were useless and "extravagant for those who are well," readers simply crossed preserves from their household lists. Nor did they dispute that "green peas should be boiled from twenty to sixty minutes according to their age." Personal experience taught her, and she passed on the information that beef chuck at four or five cents a pound made as tasty a roast as sirloin.

For faded wardrobes she suggested that bee balm steeped in water made a lovely rose dye, while saffron or the outside scales of onions gave good yellow. Birch bark, peach leaves, and the purple paper in which sugar was wrapped were each useful for color. With ingenuity and the help of Maria Child, anything fit for the dustbin came to life. Brides had Maria to thank when their husbands praised them for their housekeeping. Reviewers praised her book—all but Willis, the versifier dandy, who continued to keep himself aloof from the grubbiness of the practical world. Willis poked fun at Maria's statement that "hard gingerbread is good to have in the family; it keeps so well." He jeered that if the gingerbread were good in the first place, it would not be there to keep; and he had nothing else to say about the book. But Willis and his sneers were a long way from her present life; and though he might prick, he could not really hurt her, and the public in general gave her nothing but praise.

Again she wrote to Mary, "My Miscellany succeeds far beyond my most sanguine expectations. That is people are generous beyond my hopes." It was the same about the Housewife. The North American Review, highest literary authority of America, said: We are not sure that any woman of our country could outrank Mrs. Child. This lady has long been before the public with much success. And well she deserves it, for in all her works nothing can be found which does not commend itself, by its tone of healthy morality and good sense. Few female writers if any have done more or better things for our literature in the lighter or graver departments. Maria was a terribly exacting editor for her Miscellany. Rather than compromise on quality or time schedule, she wrote much of the copy herself.

When William Cullen Bryant was late with a promised contribution, she wrote to him that she was very sorry but that she had filled the space with a poem of her own, "Lines to a Fringed Gentian," a Wordsworthian bit that included these lines: Thus buds of virtue often bloom The fairest mid the deepest gloom. Bryant's poem was put aside for future publication. She had not the forsight to know that while her piece was sweet, his would gain posterity. Between times, she wrote her third novel, First Settlers of New England, and compiled some of the Miscellany pieces into a thin volume, Souvenir of New England. Then she edited the Coronal, the best of her published verse and stories. She hadn't much respect for her own poetry but her uncritical critics insisted that some of it ranked with the best of its time and her "Marius Amid the Ruins of Carthage" appears to this day in anthologies.

Her story, "Adventures of a Raindrop," was often credited to another author then still virtually unknown—Nathaniel Hawthorne. Not even her closest friends could understand how Maria covered as much ground as she did: writer, editor, head of the literary department of the newspaper, The Boston Traveller, one of three superintendents for a girls' school on Dorchester Heights, and homekeeper for David. If she skimped on any of her activities, it was never one which concerned him. Guests came as often as they were invited— wangled invitations, in fact, for her dinners of rack of lamb, cod dressed in herb sauce, brandied cherry pudding, and homemade beer, each dish as beautifully arranged as it was good to taste. But not even the stoutest, most energetic spirit can work endlessly without suffering for it, and Maria grew thinner and more pinched until David, who could not leave his law practice or his editor's chair, urged her to take a quiet holiday alone at Phillips Beach.

She was no sooner there than she longed to be back, and wrote to him: Dearest Husband: Here I am in a snug little old-fashioned parlor in a rocking chair and the greatest comfort I have is the pen-knife you sharpened for me just before I came away. As you tell me sometimes, it makes my heart leap to see anything you have touched .. . I went down to a little cove between two lines of rock this morning and having taken off my stockings, I let the saucy waves come dashing and sparkling in my lap. I was a little sad because it made me think of the beautiful time we had when we washed our feet together in the mountain waterfall. How I do wish you were here. It is nonsense for me to go a-pleasuring without you . . . my private opinion is that I shall not be able to stand it for a whole week. She got home as fast as she could and they decided that living in the hubbub of town put too heavy a burden on her nerves.

Boston's close-built houses, the seventy-five thousand people who thronged the streets and markets, the noise and bustle of roving, be-earringed and bedaggered sailors, of the high two-wheeled carts that clattered up and down the cobbled hills, the babble of thousands of immigrants and street vendors who sold anything from thimbles to rutabagas, and the loss of the last aspects of rurality by the banishment of cows from the Common, made her long to breathe fresh air and sleep through quiet nights. Even the inducement of running water which gushed through log conduits all the four miles from Jamaica Pond, could not keep her in the city; and though it meant that she would herself have to make a great many things including soap which the shops in town easily provided, she was ready for the move. In the latter part of 1832, the Childs found a house that was just right. It was in this small home on Cottage Place in Roxbury that Maria realized her greatest happiness.

Everything she had ever hoped for was hers, except a child, and if one had come to her then, life would have taken a different turn. But nothing else lacked, for David was her all and, for the moment, even he was in a better position financially as a Boston justice of the peace. Mr. Francis lived nearby on Dorchester Heights, near enough to visit them or for them to go to him frequently. She could write without interruption, and when her fingers or back cramped she had only to step to the door to watch the clouds shift or rainbow lights come shimmering through the rain. Or work for an hour in her flower and herb garden while the peepers announced the spring. Or hear the high, thin call of the cedar waxwing. When she did have to go to Boston, she trudged the full three miles along Washington Street instead of paying twenty-five cents for stagecoach fare.

She could always rest at the Boston Athenaeum on Pearl Street at the end of the trek because she had held a complimentary privilege at the library ever since she had written Hobomok. The Athenaeum was distinctly a man's organization, and outside of Hannah Adams, the eccentric historian, Maria was the only woman accorded that privilege. Members asserted that ladies were barred because their full skirts made it dangerous for them to navigate the narrow, spiral iron stairs; but either the plain dress of Miss Adams and Mrs. Child lulled their fears or the gentlemen respected the "men's minds" of these two ladies. Maria used the library extensively, for it carried newspapers from anywhere in the United States or Europe provided the editorial policy was conservative. The ledger for 1832 still carries the list of the books Maria borrowed to take back to Roxbury, a long list headed by the words: "Mrs. D. L. Child—free by vote of the Trustees until further order of the Trustees."

Elizabeth Peabody, who was given a six-month permit at the Athenaeum, thought herself lucky to get even that, but Maria for the moment was Fortune's child. The Housewife had sold out in ten editions in America alone and more in France and England, her Mothers' Book and her Little Girls' Own Book had gone through several printings. Margaret Fuller, not yet a writer though already a great talker, saw Maria examining a copy of the English edition of the Mothers' Book in the Athenaeum reading room and commented that the author deserved all the honor fame and hard work had brought her. Back in Watertown several years earlier, Maria and Margaret had studied the lives and works of Madame de Stael and Madame Roland, writers relatively unappreciated in the New World.

At the Athenaeum, Maria continued her study of the impact and influence of these Frenchwomen and made them the first subjects in a series of five books on the history of women. She called her series The Ladies' Library. Again the books sold, almost as well as the previous ones, and again she was praised as a pattern of womanhood, the ideal of her generation, though a few perceptive readers began to wonder whether something more serious was brewing under her sweetness and light. Could it be that this model of propriety was faintly sounding the tocsin for the emancipation of women?”

- Helene G. Baer, “The Frugal Housewife.” in The Heart Is Like Heaven: The Life of Lydia Maria Child

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#19

PREFACE.

The piety and chivalry exhibited by those Christian warriors, who, at an early period of European civilization, left their homes and their countries to rescue the Holy Sepulchre from the grasp of Moslem conquerors, have since seldom — save in the case of men too skeptical to sympathize, or too stupid to comprehend — failed to excite admiration and curiosity. My object, in this book for boys, is to give an idea of the heroes who, animated by religion and heroism, took part in the battles, the sieges, the marvellous enterprises of valor and despair, which make up the history of those great adventures known as the Crusades.

I have endeavored, I would fain hope not with out some slight degree of success, to narrate the events of the Holy War, from the time Peter the Hermit rode over Europe on his mule, rousing the religious zeal of the nation, to that dismal day when Acre, the last stronghold of the Christians in the East, fell before the arms of the successor of Saladin and of Bibars Bendocdar. [19]

End of page

Source: Edgar, J. G. (John George). (1860). The crusades and the crusaders. Boston: Ticknor and Fields.

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008437825/Cite

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

“Did everyone else come with a date?” with Charles Sumner please.

This did not go in a direction either of us probably anticipated, but I’m on this particular kick lately and I cannot help myself:

Charles Sumner stared at

the invitation grasped firmly in his hands, still in utter disbelief that he

was going. Yes, he had befriended George Ticknor ages before, and had attended

countless parties thrown by Ticknor and his wife. It was commonly accepted in

and around Boston that any party that the Ticknor’s threw was considered the

event of the year, and to be invited was a great honor. Once again, Charles had made their list. Despite that fact, it was still a shock to him that

people seemed to enjoy his company at all. Self-doubt was crippling that way,

and though he agonized over the intrusive thoughts, he accepted the invitation

all the same.

He didn’t live too

far from them, so he decided to walk, hoping it would help calm his nerves. He found

himself in the main hall about 15 minutes later, a little cold but no worse for

wear. Before he had even fully pulled his coat off, a familiar voice rang out

from down the hall. “Charles!”

Fanny Longfellow

looked positively radiant at the foot of the stairs, waving him over as

excitedly as propriety allowed. “I’m so happy you’re here,” she whispered as he

stepped beside her. “I hear the Ticknors have a special surprise for us this

evening.”

“Do they?” Charles

asked, vaguely curious. His main goal for the evening was simply trying to survive

it, but if the Ticknors had some sort of Christmas surprise, that could

potentially be a bit of fun.

“No one knows exactly

what, but I have some guesses.” Fanny grinned, taking his arm.

It was at that

moment he noticed something important was missing from the scene. “Where’s

Henry?”

“Probably talking

with Corny, I’d wager. Or sampling the wine table,” she laughed, giving his arm

a squeeze.

“And why are you

standing here all by yourself?” he asked, patting her hand gently.

“I can handle

myself every once in a while. Though present company is certainly a marked

improvement.” Charles’ cheeks reddened at that, but he smiled all the same.

“Shall we?”

“We shall.”

Arm in arm, the

two of them made their way to the main ballroom. Henry, sure enough, was off to

the side, sipping a glass of red wine. The Ticknors were parading around the

room triumphantly, King and Queen of their own tiny little kingdom. Friends and

acquaintances alike were dancing the night away or talking happily in the

corners. Children ran around the room, firing off poppers and playing games. It

was picture perfect, like something out of a story book.

The ballroom

itself was filled with garlands of holly draped artfully along the walls, and wreaths

hanging quaintly in the windows. In the center of the room stood a table, with

a large screen standing upon it. Beside the screen were sundry presents, each

addressed to one of the young boys and girls in attendance. Charles wondered

what was hidden behind the screen, but Fanny seemed even more curious than he

did.

With Henry and

Fanny now by his side, Charles seemed to visibly relax, though something tugged at the back

of his mind. He couldn’t place it at first, but as more and more people

trickled in, he realized just how paired off all the adults in the room were.

“Fanny…” he

finally asked, after chatting away with her and Henry for a while. “It could be

my imagination, but… did everyone else come with a date?”

Henry and Fanny surveyed

the room. It wasn’t entirely the

case. It would have been almost impossible for Charles to be the only one

present without a plus one. There were certainly others in his shoes, but far

less than one would expect at such a large party. Even the teenagers in the

room seemed to have paired off for dancing and courting- their parents keeping

close, watchful eyes on them.

Fanny smiled,

taking Charles’ hand. “Not quite... Tom certainly didn’t.”

Sure enough, Fanny’s

brother had also come to the party alone, but unlike Charles he savored being

the center of attention and found himself surrounded by a large group of admirers.

Henry also smirked,

putting the glass of wine down and squeezing Charles’ arm reassuringly. “You’re

not alone, Carlos. Especially with us.”

Charles nodded, unconvinced.

“It’s true,” Fanny

pressed. “You’re one of us, aren’t you?”

As Henry and Fanny

both stared up at him expectantly, Charles felt the heat rising to his face

again. Uncomfortably clearing his throat, he nodded, trying to avoid eye

contact. Perhaps he had imagined it, but he could have sworn he saw Henry and

Fanny wink at one another.

“Attention!

Attention!” Ticknor suddenly yelled, a bright smile on his face. “Everyone, make

a circle now- children in front of me, there we go- now, before we get to

presents, it’s time to show you what our grand surprise is.”

As the trio made

their way closer to the center of the room, the lights around them began to

dim.

“Merry Christmas,

my friends,” Ticknor smiled, and with a wave of his hand the servants pulled

the folding doors of the screen, revealing a beautiful Christmas tree inside.

The children

gasped with delight to see the tree done up in gold and red, with candles illuminating

its branches. Henry and Charles smiled, both wrapping an arm around Fanny-

Charles somewhat more tentatively. Fanny didn’t seem to notice, completely

enraptured by the sight before them.

“I’ve never seen

one before,” she whispered reverently, looking far happier than all the

children around her.

“Let’s make it a

tradition, then,” Henry replied, kissing her cheek. “What do you say, Carlos?”

“It’s very…

German.” Charles responded awkwardly, trying and failing to be helpful.

Fanny just laughed,

still captivated. “Someday you’ll feel Christmas spirit, Mr. Sumner. Someday.”

“I assure you, Mrs.

Longfellow. This is the most I’ve felt in a very long time.”

Fanny and Henry

both looked up at him again with the warmest expressions on their faces. Charles returned the look, pulling them both a little closer.

As the three leaned

into one another, happily observing the odd new tradition in front of them, Charles couldn’t help but feel that this was exactly where he belonged.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

William H. Prescott American historian

William H. Prescott

American historian

1843), along with also his History of the Conquest of Peru, Two vol. He's been known as America's first scientific historian.

Life And Works

Prescott was out of a booming, old New England household. He obtained three decades of rigorous schooling in a preparatory school led from the Jesuit John Gardiner, who infused in him a love of learning. In 1811 he entered Harvard, where his academic record was good but undistinguished; he had severe issues with math, and in after life the possibility of assessing the mathematical accomplishments of this aboriginal Mexicans nearly prevented him from finishing his work. Close to the conclusion of the junior season, a crust of bread thrown during a melee at the student commons triggered virtual blindness in his left eye; the weakness of his other eye, brought on by disease, occasionally prevented him from taking on any sort of literary work. During his lifetime, Prescott's vision appears to have fluctuated from great to complete blindness, and he frequently resorted to using a noctograph, a composing grid with parallel wires which guided a stylus over a chemically treated coating. Substantial parts of his correspondence and books were written on this gadget.

After his graduation from Harvard in 1814, Prescott's health deteriorated after strikes of what seems to have been an intense form of rheumatism, together with swellings in his bigger joints and lower thighs. He convalesced in his grandfather's house at the Azores after which, supported by an apparent comeback, toured Europe. Following his return on Boston, he stumbled upon deep historical studies, shunning a career in business or law since both occupations needed more endurance than his fragile health and vision could allow. With no apparent occupation, he had been called"the gentleman" by his Boston friends. His wife, in addition to some other readers, given the eyes which aided Prescott at this opportunity to set off on a literary profession.

His first book was a variety of essays and reviews from the North American Overview at 1821. A few of them were reprinted in Biographical and Critical Miscellanies (1845). His"Life of Charles Brockden Brown" (1834) at Jared Sparks's Library of American Biography served notice of Prescott's top skills as an author. Mostly on the recommendation of his friend the instructor and author George Ticknor along with also the subsequent encouragement from the mixed author Washington Irving, Prescott turned into Spanish topics for his lifework. The look in 1838 of the three-volume History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic, the merchandise of a 10 decades of work, was a pleasant surprise to Boston's literary universe. This work started Prescott's career as a historian of 16th-century Spain and its own colonies. (1855--58), Prescott created devious, authoritative narratives of Spanish military, diplomatic, and political background that had no equivalent in their own time. Prescott's contemporary popularity, however, rests with his epic poem History of the Conquest of Mexico along with his History of the Conquest of Peru.

Working with a great personal library of possibly 5,000 volumes and with the support of such overseas partners as Pascual de Gayangos, the president that found manuscripts and rare books for him, Prescott made extensive usage of original sources. His crucial use of historical evidence was such he may well be known as the first American scientific historian.

Rea more about William H. Prescott

0 notes

Text

British Library digitised image from page 75 of "Childe Harolde's Pilgrimage ... New edition"

Image taken from:

Title: "Childe Harolde's Pilgrimage ... New edition"

Author(s): Byron, George Gordon Byron, Baron, 1788-1824 [person]

British Library shelfmark: "Digital Store 11645.ff.41"

Page: 75 (scanned page number - not necessarily the actual page number in the publication)

Place of publication: Boston

Date of publication: 1886

Publisher: Ticknor

Edition: Another edition, Illustrated

Type of resource: Monograph

Language(s): English

Physical description: 236 pages (8°)

Explore this item in the British Library’s catalogue:

004112484 (physical copy) and 014832802 (digitised copy)

(numbers are British Library identifiers)

Other links related to this image:

- View this image as a scanned publication on the British Library’s online viewer (you can download the image, selected pages or the whole book)

- Order a higher quality scanned version of this image from the British Library

Other links related to this publication:

- View all the illustrations found in this publication

- View all the illustrations in publications from the same year (1886)

- Download the Optical Character Recognised (OCR) derived text for this publication as JavaScript Object Notation (JSON)

- Explore and experiment with the British Library’s digital collections

The British Library community is able to flourish online thanks to freely available resources such as this.

You can help support our mission to continue making our collection accessible to everyone, for research, inspiration and enjoyment, by donating on the British Library supporter webpage here.

Thank you for supporting the British Library.

from BLPromptBot https://ift.tt/2RtdVzH

0 notes

Photo

Image from '[Childe Harolde's Pilgrimage ... New edition.]', 004112484

Author: Byron, George Gordon Byron Baron

Page: 63

Year: 1886

Place: Boston: Ticknor & Co., 1886

Publisher:

View this image on Flickr

View all the images from this book

Following the link above will take you to the British Library's integrated catalogue. You will be able to download a PDF of the book this image is taken from, as well as view the pages up close with the 'itemViewer'. Click on the 'related items' to search for the electronic version of this work.

#bldigital#bl_labs#britishlibrary#1886#similar_to_168497935772_published_date#similar_to_168497935772_slantyness#similar_to_168497935772_bubblyness_avesize#face_detected_555left_623top_846right_914bottom

1 note

·

View note

Text

Anna Cora Mowatt, Mimic Life, and the Critics

Anna Cora Mowatt, Mimic Life, and the Critics

Part II: The Push

[Given the response to my last entry, I am somewhat tempted to take a short vacation from writing about Anna Cora Mowatt and devote more time to relating my adventures in grad school with my somewhat portly portable computer. I would give you her name, but I must confess that she did not have one. Frankly I tried to avoid emotional attachments to electronic equipment because…

View On WordPress

#anna cora mowatt#Autobiography of an Actress#Boston Evening Transcript#charles dickens#E.D.E.N. Southworth#epes sargent#Fanny Fern#George Ticknor#Harriet Beecher Stowe#J.W.S. Hows#James T. Fields#Marylebone Theater#Mimic Life#The Albion#theatrical autobiography#Ticknor and Fields#Victorian Actress#Victorian theater#victorian theatre#Walter Watts#William Foushee Ritchie

0 notes

Photo

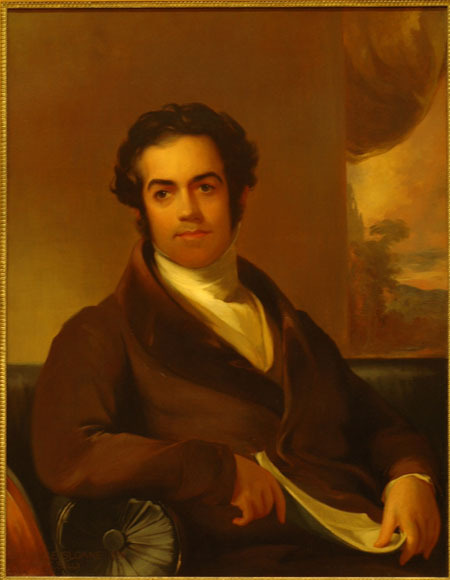

George Ticknor, 1831, Thomas Sully

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

george ticknor looks like the kind of wildcard bitch who would run thru the boston commons drunk at night with daniel webster

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Curtis and Curtis on Patents

Benjamin Robbins Curtis — The only patent attorney to serve on the US Supreme Court. He dissent in Dred Scott and resigned in the aftermath.

His brother, George Ticknor Curtis was the more famous patent attorney — author of "Curtis on Patents" (1st ed. 1849). pic.twitter.com/y4xWpvg5GB

— Dennis Crouch (@patentlyo) July 14, 2020

Curtis and Curtis on Patents published first on https://immigrationlawyerto.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

The Count of almost every French province maintained a state which threw royalty into the shade. When at peace, his board was surrounded by seneschals, cup bearers, and pages, falconers and minstrels.

When at war, his banner was attended by knights, squires, and grooms, vavasours and varlets. #38 (p.2)

Source: Edgar, J. G. (John George). (1860). The crusades and the crusaders. Boston: Ticknor and Fields.

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008437825/Cite

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ticknor Society Announces Book Collecting Prize for New England-Based Bibliophiles

Ticknor Society Announces Book Collecting Prize for New England-Based Bibliophiles @finebooks #ticknor

George Ticknor (1791-1871) was a true Boston Brahmin ardently devoted to books and learning. The Harvard University professor of French and Spanish (who resigned in 1835 and was replaced by none other than Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) built a 14,000-volume personal library that rivaled institutional collections in Europe. Ticknor’s daughter, Anna Eliot (1823-1896) was also an intellectual and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Gelert #Gelert Gelert's Grave This story formed the basis for several English poems, including 'Beth-Gelert' by the Hon William R Spencer. It was first printed in a private broadsheet around 1800 and then in a collection of Spencer's poems in 1811. He stated that: "The story of this ballad is in a village at the foot of Snowdon where Llewellyn the Great had a house. The Greyhound named Gelert was given him by his father-in-law, King John, in the year 1205, and the place to this day is called Beth-Gelert, or the grave of Gelert." It also featured in poems by Richard Henry Horne, Robert Spencer, Francis Orray Ticknor and the dramatic poem ‘Llewellyn’ by Walter Richard Cassels. It is recorded in Wild Wales by George Borrow, who notes it as a well-known legend. Every year thousands of people still visit the grave of this brave dog! Unfortunately, the story may have had more to do with tourism than truth. It is widely accepted that the village took its name from a priory that was once sited there, dedicated to Saint Celert or Kilart. So how did the village name become associated with the story of the dog Gelert? Well, it seems that history and myth become a little blurred when, in 1793, a man called David Pritchard came to live in Beddgelert. He was the landlord of the Royal Goat Inn (now the Royal Goat Hotel). He merged a Welsh legend about a dog named Cilhart, buried at Beddgelert, with the story of a brave dog whose master thinks it has killed his baby son. Making up the name of Gelert, he adapted it to fit the village. His aim was to increase trade at the inn. Indeed, rather than a memorial put in place long ago by a grieving remorseful prince, the grave is actually just over 200 years old. It is thought to have been erected at the turn of the 19th century by Pritchard with the help of the parish clerk and several other villagers, in an attempt to lure Snowdon's visitors to the village and thus line their pockets. So is there any truth in the tale? Well, it is certainly true that hunting with dogs was a popular and important sport for the nobility in medieval times. So important that killing a greyhound was punishable by death, a punishment equivalent to that?

0 notes