#Japan constitution

Text

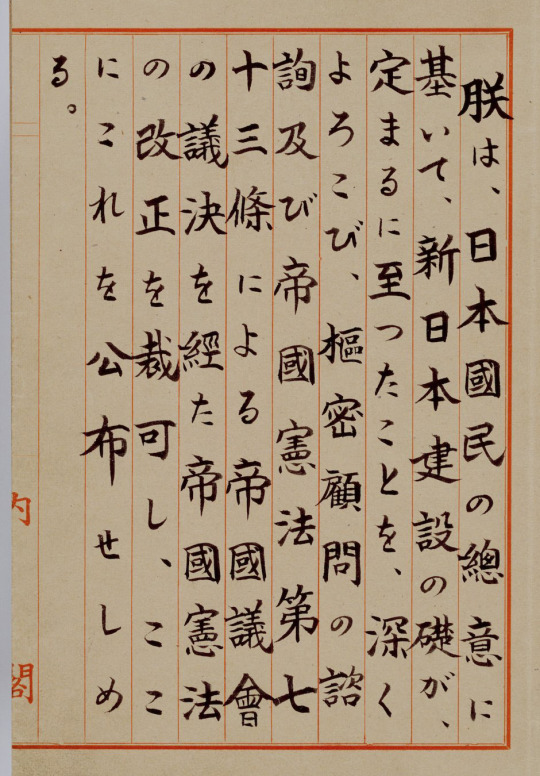

We, the Japanese people, acting through our duly elected representatives in the National Diet, determined that we shall secure for ourselves and our posterity the fruits of peaceful cooperation with all nations and the blessings of liberty throughout this land, and resolved that never again shall we be visited with the horrors of war through the action of government, do proclaim that sovereign power resides with the people and do firmly establish this Constitution. Government is a sacred trust of the people, the authority for which is derived from the people, the powers of which are exercised by the representatives of the people, and the benefits of which are enjoyed by the people. This is a universal principle of mankind upon which this Constitution is founded. We reject and revoke all constitutions, laws, ordinances, and rescripts in conflict herewith.

We, the Japanese people, desire peace for all time and are deeply conscious of the high ideals controlling human relationship, and we have determined to preserve our security and existence, trusting in the justice and faith of the peace-loving peoples of the world. We desire to occupy an honored place in an international society striving for the preservation of peace, and the banishment of tyranny and slavery, oppression and intolerance for all time from the earth. We recognize that all peoples of the world have the right to live in peace, free from fear and want.

We believe that no nation is responsible to itself alone, but that laws of political morality are universal; and that obedience to such laws is incumbent upon all nations who would sustain their own sovereignty and justify their sovereign relationship with other nations.

We, the Japanese people, pledge our national honor to accomplish these high ideals and purposes with all our resources.

The Constitution of Japan, promulgated on November 3, 1946, came into effect on May 3, 1947

#quote#Japan#law#government#Japan constitution#governance#Japanese constitution#Japanese#politics#power#constitution

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Japanese high court just declared the ban on same-sex marriage is unconstitutional! This is a major landmark in the long fight in Japan to legalize same-sex marriage. Right now there's only been a court ruling declaring that it's unconstitutional, but that sets a solid precedent to legalize it later on.

#the ban is specifically due to the wording of the constitution declaring marriage btwn a man and woman is a right#but the Tokyo high court ruled that this wording is in spirit meant to declare rights for all individuals regardless of sex#.personal#sloot in japan

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

cant believe my goal in life is to become a fucking Law Scholar now. jesus christ.

#sage talks#2 options: i become a lawyer or i become a professor and deal with fuckwad college kids#autistic girl professor who explains to you how (american) constitutional law could be related to enstars and how this shows a diffusion of#culture between america and japan. yes k can actually talk about this

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Don’t hold your breath.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do I attempt to salvage the thought I had about Fermet printing Fermetes 2+ hours ago into a post at 10:23 PM or do I salvage the 1883 words of a .md file I apparently wrote before the two hours of helping someone assemble monitor stand + cable management session began into some droll post for tomorrow?

#Baccano! Light Novel Spoilers#personal#it's probably the latter#I finally sat back down after the two hours and attempted to write said pithy post#but my already sleep-deprived brain is not having it.#*droll not pithy#*blatantly terribly written not droll#It's not even a particularly interesting or deep thought but the primordial instinct within me telling me my B! knowledge is hopelessly#wrong and that I should factcheck some of this is holding it back#(but seriously though. Fermet hive mind supervising SAMPLE branches across Europe and NA ...#(...these not quite carbon copy Fermets but /very/alike Fermets just. supervising the multi-continent perpetuation of#~child torture cult~#(hm. yes. how will these SAMPLE seeds sprout in America. I know. I shall water them personally but allow them to blossom idiosyncracies)#(I'm not saying that's what Fermet did. I'm just asking you to imagine hive!Fermet in Fermet-progeny homunculi cultivating their culty crops#simultaneously across two continents minimum - three actually (Asia via Japan) - for however many years (???decs???) it's been since#Fermet cottoned on to whatever constituted proto hivemind alchemy#Wow it's easier to write and post things to Tumblr in the sweet sweet informal casual atmosphere of tags#and not the formal 'wuh woh your content may be treated seriously' posts themselves.This doesn't count as a post...#(Really definitely not saying that. Nothing I say in these tags counts! Take this flourish on top of the cartoon evil and be put out.)#Looks like those 1883 words also referenced Huey hive mind

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the Constitution of Japan that weakened Japan.

The pre-war Japan army was so strong that the United States was very afraid of Japan.

Therefore, in order to enslave Japan people, this constitution of the Japan country was given to Japan.

A nation cannot be established with such a constitution.

The preamble to the Constitution of Japan states that the people of Japan are "determined to ensure that the scourge of war does not again occur through the actions of their governments," "longing for lasting peace," and "relying on the justice and fidelity of peace-loving nations, to preserve our security and survival."

Article 9 declares that the government forever renounces war, the threat of force, and the use of force as an exercise of national authority.

However, are Russia, China, and North Korea peace-loving nations?

The fact that the Constitution of Japan is non-resistance and the absence of the right of belligerency is good, but China claims Okinawa as Chinese territory.

Can this Constitution of Japan protect the current Japan?

By all means, you should read this book by Dr. Nakasugi and know the true nature of the Constitution of Japan!

0 notes

Text

Facts of Japan's Constitution

Article 1

The Emperor shall be the symbol of the State and of the unity of the People, deriving his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power.

Article 2

The Imperial Throne shall be dynastic and succeeded to in accordance with the Imperial House Law passed by the Diet.

Article 43

Both Houses shall consist of elected members, representative of all the people.

The number of the members of each House shall be fixed by law.

Article 44

The qualifications of members of both Houses and their electors shall be fixed by law. However, there shall be no discrimination because of race, creed, sex, social status, family origin, education, property or income.

Article 49

Members of both Houses shall receive appropriate annual payment from the national treasury in accordance with law.

Article 58

Each House shall select its own president and other officials.

Each House shall establish its rules pertaining to meetings, proceedings and internal discipline, and may punish members for disorderly conduct. However, in order to expel a member, a majority of two-thirds or more of those members present must pass a resolution thereon.

by Dunilefra, working for Political Reform

#Japan#Dunilefra#Politics#Political Reform#World Politics#World Order#Fundamental Rights#Human Rights#Economy#Religion#State Policy#Political Analysis#Constitution#Constitutional Law

1 note

·

View note

Text

1948- Constitution Day Japan.

The Constitution of Japan (Shinjitai: 日本国憲法, Kyūjitai: 日本國憲󠄁法, Hepburn: Nihon-koku kenpō) is the constitution of Japan and the supreme law in the state. It was written primarily by American civilian officials working under the Allied occupation of Japan after World War II. The current Japanese constitution was promulgated as an amendment of the Meiji Constitution of 1890 on 3 November 1946 when it came into effect on 3 May 1947.

0 notes

Text

On Yoshifu Arita’s Campaign and What it Means for the UC

Tweets from @nowwarmom (link to thread) consolidated in the pragraph below.

The first tweet from @nowwarmom includes a quoted tweet from Yoshifu Arita that included a video. Google translation of the tweet: “This by-election to select the successor seat to former Prime Minister Abe, who died a violent death. It is an election that shows the fighting attitude of the Constitutional Democratic Party. It's not a shame to lose, it's a shame not to fight because you're afraid. Even in a conservative kingdom, if we spread our will, we can definitely win. Until the end, thank you for your support.” (Watch video here)

@nowwarmom’s tweets:

Voting for the Yamaguchi 4th district supplementary election following the death of ex-PM Shinzo Abe will be held tomorrow April 23. Much attention has been focused on the runoff between Yoshifu Arita, a journalist and former Diet member who has long tracked and warned about the Unification Church issues, and Shinji Yoshida, a newcomer supported by the LDP and backed by politicians with close ties to the UC. He has declared that he will carry on the will of he late Shinzo Abe. Arita has a connection to this constituency as his parents lived and met here. In this constituency, there is a town that UC believers hold in special regard as a place "worthy of sanctuary" as it was where Sun Myung Moon first stepped on Japanese soil as a student in 1941. Also, ex-PM Abe, with support from the UC, has won parliamentary elections here in a huge landslide over the years. In order for this constituency to break ties with the Unification Church, Arita’s win is essential.

#cdp#constitutional democratic party of japan#japanese politics#constitutional democratic party#japan#yoshifu arita#politics#unification church in japan#unification church#shinzo abe#kishi family#shinji yoshida#ldp#liberal democratic party#conservative politics#right wing politics#right-wing politics#right-wing#ffwpu#family federation for world peace and unification

0 notes

Text

“The nation of Manchukuo was theoretically founded on a complex and fairly contradictory mix of principles, leaving the role of law in the new society somewhat unclear. At its most basic level, the creation of an independent Manchukuo was represented as a triumph of popular sovereignty, the “unanimous will of the thirty million people of Manchuria and Mongolia,” a portrayal that fit well with Wilsonian ideals of democratic self-determination. For many, such claims rang hollow even at the outset and appeared to be aimed largely at convincing Western powers of the legitimacy of the new state. But they do imply a degree of affinity for the dressings, if not the genuine ideals of liberal government, of which the rule of law under a free and independent judiciary would be paramount.

At the same time, even if the foundation of Manchukuo theoretically represented an act of popular will, it was still very much a created society. Japanese superiority was never in doubt. The rhetoric of statehood aside, the paternalistic attitude that Japan took toward nominally independent Manchukuo made it difficult to distinguish from a colony. This was not simply a matter of Japanese duplicity; many of the Chinese intellectuals who would take up positions in the Manchukuo government had openly argued that China would benefit from a period of foreign stewardship. As was the case in Taiwan and Korea, the institution and reform of law in Manchukuo was part of a package of civilizing methods imposed from above and from without, constructing a society while protecting a privileged place for Japanese citizens and interests therein.

Tension between these ideals was further complicated by the rhetoric of what made Manchukuo unique. In its own propaganda, Manchukuo was not merely independent. It was a radically new and uniquely Asian form of polity, an incarnation of Japanese spiritualism taking root in a multi-ethnic state, and thus, even more than Japan itself, an exemplar for the political future of pan-Asianism. What role should law play in a country ruled by this unlikely mix of Asian morality and hyper-modernism, legitimized in terms of Western liberalism, yet openly disdainful of it?

Given the somewhat schizophrenic ideals officially espoused in its founding, it is not surprising to see law in Manchukuo represented in a number of strikingly different ways. Manchukuo was established amid a heavy dose of legal rhetoric, and some of the first acts taken after its founding were legal in nature. These included an appeal to the principles of international law to assure the legitimacy of the new state and promises to create a legal system in order to “protect the livelihood of the people, and increase their wealth and stability.” At the core of this new system, the 1932 Organic Law (Law of the Organization of the State of Manchukuo, Manshu koku no seiji soshiki ho) outlined the structure of government and included a twelve-part Human Rights Protection Law. On its face, the government structure appeared designed to balance power between legislative bodies and the executive branch. To ensure the independence of the courts, the judiciary was to be a distinct branch of government, judges were appointed for life, and all judicial organs were financially under the central government so as to avoid the corruption that had supposedly characterized the previous justice system.

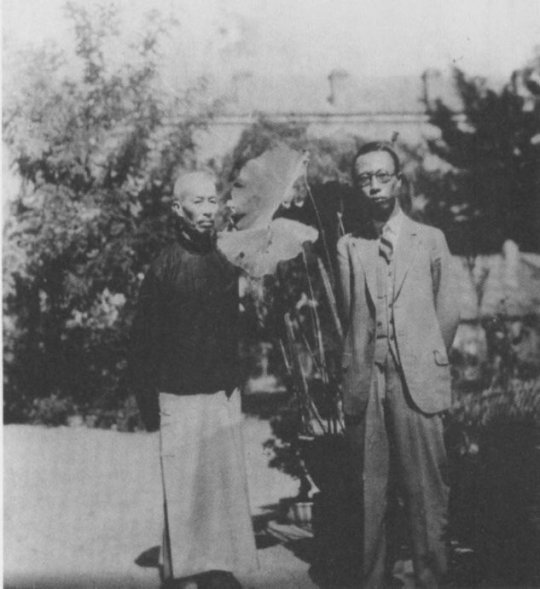

Despite the appearance of balance within the government, the entire state structure rested on the foundation of an external, spiritualist authority. Even if the state was founded on the principles of popular will, it did not serve this will through elected representation, but rather through a spiritual bond between the state and people known as the “Kingly Way” (wangdao). The theory of the Kingly Way was largely the personal project of Zheng Xiaoxu (1860–1938), a former official of the Qing empire, constant companion of the deposed emperor Pu Yi during the 1920s, and first prime minister of Manchukuo. It represented an attempt to meld the rhetoric of Confucian moral governance with the machinery of a modern state, thus creating the foundation of a new Asian polity. In all of its public pronouncements, the new state emphasized this spiritual core, voiced alternately as the Kingly Way or later as the equally vague “spirit of national foundation” (jianguo jingshen). The short declaration establishing the government of Manchukuo, uttered by the titular head of state (although not yet emperor) Pu Yi on March 9, 1932, is typical of the moral rhetoric of Manchukuo:

Humankind must value morality. Yet there is a difference between races—in which some control others while praising themselves. Such morality is very thin. Humankind must value benevolence and love. Yet there is war between nations—in which people seek to profit from other’s loss. Such benevolence and love is very thin. Our Nation has been founded on morality, benevolence and love. When racial difference and international war have been eradicated, we will see the establishment of a true paradise of the Kingly Way. The citizens of Our Nation must devote themselves to this task.

Such statements are interesting not only for their somewhat saccharine portrayal of the new state, but equally so for what they do not mention. While these pronouncements emphasize the spiritual renaissance of the Kingly Way, they generally lack reference to law, procedure, or efficiency. Even those portrayals, such as the Declaration of Manchukuo Statehood (Manshu koku kenkoku sengen), that justify the creation of the new state in terms of popular welfare, criticizing the old regime as incompetent, corrupt, and thus unable to protect the people against the twin evils of Communism and banditry, do not speak of the new state in terms of the restoration of law and order as much as this new, moral attitude toward governance.

Above: Zheng Xiaoxu and Puyi in the 1930s

This is not to say that the new state was hostile to law, but rather that law was portrayed as an expression of the same spontaneous sentiment that had created independent Manchukuo. As such, law was depicted as consensual, an expression of values and purpose held in common by state and citizens. Despite its name, the Human Rights Protection Law clearly subjected individual interests to the needs of state. There was no question of this or any other law serving to safeguard the rights of individuals against the state, the idea of any such antagonism being viewed as a leftover of individualistic bourgeois liberalism. In Manchukuo, this was portrayed as Asian consensus culture reasserting itself against selfish Westernism. But the claim that “the people” are of one mind with the government and its institutions are common to totalitarian states.

The rhetoric of morality permeated official discourse in Manchukuo, and within it, law was treated primarily as a practical measure. Although many schools of Chinese philosophy had traditionally disdained law as corrosive of public morality, in Manchukuo it was invoked as a means to attaining the moral ends of good governance. However, even if the balanced structure of the Manchukuo government was put into place in order to maintain oversight of “government morality” (seiji dotoku), the nature of this moral end was often left unclear. Occasionally it was represented in terms of economic good. The Human Rights Protection Law itself includes the commitment of the government to protect citizens against usurious interest rates, or any other form of “improper economic oppression.” However, hostility to anything resembling Sun Yat-sen’s political doctrine of the “Three Peoples’ Principles” (which included a provision for “Peoples’ Livelihood”) and an intense paranoia over the advance of Communism ensured that this type of economic rhetoric would always remain somewhat muted.

More often it was represented in terms of the spiritual and moral destiny of the state, and later of the Japanese Empire. Through the rhetoric of the Kingly Way, the emperor was held up as the concrete expression of the spiritual foundation of the new state from which all political and moral authority proceeded. Closing a long essay on the history of Manchuria, Japanese army captain Okada Meitaro waxed poetic about how under the guidance of the emperor, the ruler and people were one (kunmin ikka). Interpreting this often-repeated formulation to include the state would not be precisely accurate. The spiritual bond was that between the people and the emperor himself; the state and its institutions were necessary only as they were practical. The law itself was not inviolable because, according to the somewhat vexing logic of one source, “from the legal standpoint, the Emperor is the source of all authority.” While the rhetoric of imperial divinity would take on a much greater significance during the 1940s, even in this earlier period, the division between the emperor and government mirrored that between the moral basis of the state and its everyday procedural concerns. At a fundamental level, the law of Manchukuo was a celebration of this same consensus, a concrete expression of social harmony and universally held values, and only secondarily a tool of practical governance.

At the same time, the appeal to law was important for legitimating Manchukuo in the eyes of the outside world. In a general sense, possession of a modern legal code was held up as a hallmark of an advanced civilization, a designation that Japan itself had worked long and hard to attain. Over the previous decades, attention to international criticism had motivated not only the revision of criminal procedure inside Japan, but also the laborious attempt made to justify events such as the annexation of Korea not simply by force of arms, but within the letter of international law.

The most prized mark of Japan’s entry into the family of “civilized nations,” and the standard for which they fought tirelessly in Manchukuo, was revision of extraterritoriality. This provision was introduced by many Western powers in their treaties with China and Japan (and later by Japan in China and Korea) and allowed the former to try its own citizens for offenses committed within the territory of the latter, on the grounds that Asian judicial systems were excessively violent and unreliable. For western-oriented reformers in Meiji Japan, such a characterization had been particularly grating, and with the help of European advisors, Japan had managed to reform its code to secure abrogation of extraterritoriality by the late nineteenth century. It now faced a similar battle in Manchukuo by virtue of preexisting treaty obligations on what had previously been Chinese soil.

However, the decision for Manchukuo to honor extraterritoriality clauses in existing treaties was made voluntarily by Japan. It was motivated by two considerations, the desire to court Western approval for the new state and, more fundamentally, the need to maintain the special rights enjoyed by Japanese commercial interests (particularly in the semi-colonial territories administered by the South Manchuria Railway) and citizens until a judicial system tailored to Japan’s liking had been established. As such, the road to ending extraterritoriality turned around two somewhat contradictory principles: the manipulation of the Manchukuo judicial system to enshrine special rights for Japan and the courting of other extraterritorial powers (all Western) to recognize these changes as reforms and voluntarily surrender their own rights.

The high profile of this emotional issue is seen in the amount of attention it received in legal circles in Manchukuo and Japan. In December 1933, a joint conference of thirty-six Japanese and native officials of Manchukuo convened in the city of Fengtian to discuss the legal basis of Japanese abrogation of extraterritoriality. This was followed by a series of similar meetings in 1934 and 1935. Nor was the attention to this question restricted to Manchukuo; these meetings were widely publicized within Japan, in no small part to mollify fears among domestic investors and settlers over a potential loss of Japanese privileges in Manchuria.

In an allied effort, the new government immediately began taking steps to promulgate a constitution. Diplomats observing the new state had expected such a step to be taken immediately and, through 1936, were promised the immanent release of a Manchukuo constitution. They were somewhat mollified by the promulgation of the Organic Law in 1932, which was then revised in 1934 to reflect the accession of Pu Yi to emperor. The delay in promulgating the actual constitution was a surprise to observers, many of whom were already convinced that this would be nothing more than a cosmetic document, imposed by Japan with little debate or controversy.

Yet controversy there was, because the constitution of Manchukuo could potentially establish precedents that would influence the entire empire, including Japan itself. Although legal scholar Mitani Takeshi characterized the Manchukuo Constitution as an imperfect copy of the 1889 Meiji Constitution, the structure of government outlined in the 1932 Law of the Organization of the State of Manchukuo was in fact adapted largely from the Republic of China. This was primarily to ensure a smooth transition between the two governments, but also because Chinese and Japanese jurists and jurisprudence were already quite close. Indeed, the Chinese government structure and legal codes as they appeared in the 1930s had themselves been very heavily influenced by Japanese advisors a generation earlier.

Nevertheless, small but revealing differences separated Manchukuo from both China and Japan. Like that of the Republic of China, the government of Manchukuo was divided into Legislative, Judicial, Cabinet and Oversight Yuan, the latter omitting the Examination Yuan. Other differences were more fundamental. While the both the Chinese Legislative Yuan and the Japanese Imperial Diet had the power to propose, pass, and veto laws, the Legislative Yuan of Manchukuo was restricted to assisting (yokusan) in this function. The Manchukuo Legislative Yuan did have the power to reject laws, but this rejection was not binding and could easily be overturned. In theory, this was because the Manchukuo legislature was not an expression of popular will, but rather of imperial benevolence, and served at the convenience of the emperor. According to Mitani, it also reflected the image that some had for the future of Japan, with power centralized at the expense of a severely weakened Imperial Diet. Given its lack of any real power, it was very difficult to find recruits for this body; British consular reports paint a rather sad picture of the 1934 Manchukuo legislature as thirty-nine “more or less reluctant nominees of Japan.”

- Thomas David Dubois, “Rule of Law in a Brave New Empire: Legal Rhetoric and Practice in Manchukuo,” Law and History Review Summer 2008, Vol. 26, No. 2: p. 291-298.

#manchukuo#manchuria#state of manchuria#滿洲國#ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ#legal code#empire of law#history of crime and punishment#constitutional government#puyi#governmental law#chinese history#empire of japan#jurisprudence#academic quote

0 notes

Text

Demystifying golden week- What is Golden week again?

It's golden week. Thought you all should know :P

Heyo! It’s golden week! What is golden week? So glad you asked! Golden week also known as Ogon Shukan is a special streak of 4 holidays that is celebrated in Japan. Showa Day (Showa no hi) which happens on April 29, Constitution Memorial Day ( Kempo Kinenbi) which happens a few days later on May 3, Greenery Day (midori no hi) the following day on May 4, and Children’s Day (Kodomo no Hi) as the…

View On WordPress

#boy&039;s day#children&039;s day#constitution memorial day#Demystifying#Demystifying golden week#greenery day#japanese holidays#Showa day#what are some japanese holidays that happen in the spring?#what is golden week#what is Ogon shukan?#when is golden week in japan?

1 note

·

View note

Text

LRT is really significant because what constitutes "being a good conversation partner" or even "being a good audience" is really, really culturally contingent. A white American preacher holding an audience silent for five minutes is doing a good job, a black American preacher holding an audience silent for five minutes is dying on his ass. In the monoculture interrupting during someone's train of thought is considered rude, there are many cultures where this is the case, but by contrast the Jewish conversational mode is "respond to the train of thought with your own to show engagement" and not responding indicates indifference or even hostility, and on the opposite extreme in Japan it's apparently normal to respond to basically every clause of a conversation partner's speech with some kind of noise - grunts, echoed phrases, words of agreement, etc - to show that you're paying attention and understand what they're saying

848 notes

·

View notes

Note

CT, is an onmyōji a kind of wizard? Do they fit in the Wizard topology or are they their own thing?

This is one of those "You could get a PHD trying to answer this" type questions. But in the interest of blogging, let's give it as much of a shot as a Tumblr post will allow.

Let's take this question seriously for a moment, and use a more academic term: "Is an Onmyoji a magician, as in a person who does magic?"

The hard part about answering this question is "how do we define magic?" So let me lay down some quick criteria I've gathered from different anthropology and archeology texts over the years:

Magic is a technical practice, it is something that can be taught and learned.

Magic tends to operate on principals of similitude, rather than experiment. I.e. "gold and the sun are connected because they are similar in color."

Magic tends to serve some material social role, regardless of any claimed supernatural elements. I.e. "There might not be a literal demon inside you, but the ritual of having the town come together and support you has material benefits."

By these criteria, and from my fairly limited understanding of Onmyoji, I think you could absolutely classify Onmyoji as sometimes practicing magic. However, it's important not to stop here. Their role in the religious/spiritual landscape of Japan is fairly complex. Where exactly we draw the lines around what does and does not constitute "magic" in this context is for someone smarter and more informed than me.

That done, let's take the question less seriously for a moment: yes Onmyoji are magicians because in the video game Nioh 2 they refer to onmyo practices as "onmyo magic."

485 notes

·

View notes

Text

the spoon does not exist. - movie scene linked

the straight spoon does not exist without your awareness of it.

you do not bend the spoon, you bend yourself. you bend your awareness. the spoon is illusory. perception is subjective.

"What he sees before him is not a spoon, but rather an idea his brain has created of a spoon—his own perception. He can change reality by changing his perception."

"Neo remembers this exchange as he becomes more confident in his ability to break the rules of the Matrix. All he has to do is remember that the rules he breaks aren’t actual rules. Just as there is no spoon, there is no gravity, there is no time—all these things are lies the machines tell his brain. Neo can fly, for example, because he can see gravity is a false construct. Once Neo understands that “there is no spoon,” he gains more power in the Matrix."

using a movie to explain that reality is false may be unorthodox but hear me out. the matrix is simply a sense-based prison. a self-made prison made up of limitations and false constructs. there is no logic, there are no facts, everything is illusory and can be changed but in order for you to gain awareness of a different version of reality you must realise that the spoon is fake.

"Anything is possible in the Matrix, yet Neo’s lifetime of conditioning within this system has kept his belief in his own ‘Oneness’ from truly taking root. Logic implies that all things are known and must follow certain parameters and patterns, yet nature is anything but logical. In this context, "there is no spoon" is meant as a means for Neo to let go of his logical presumptions of what constitutes reality. As the boy says, “...you’ll see that it is not the spoon that bends, it is only yourself.” The limitations of Neo’s reality are self-imposed by the lense through which he’s been taught to see the world. By letting go of what he’s so sure ‘he knows’, he finally opens up to what’s possible."

Morpheus tells him “You have to let it all go Neo; fear, doubt, and disbelief.”

the movie itself does give way to things external to the person - agent smith - but you do not need to take it literally. there is no external. the only agent smith that exists is your own self imposed destruction. 'breaking out of the matrix' is just breaking out of a falsely identified with reality and realising that you are above any human law, above everything for you are reality itself. be nonchalant to agent smith, he is POWERLESS for you have realised the truth. the truth that you can manipulate the so-called matrix. the truth that your realisation of your power is all that is needed.

it is hard to realise that everything you believed was real is illusory, it can be overwhelming to 'take the red pill' and realise the greatest truth that you ARE the creator and no human law applies to your divine nature. realising the truth does not take away from special moments or imagined memories, it liberates you from believing that this body is all that you are. it opens a new door of actual UNLIMITED possibilities to experience anything you want to experience, knowing that you are not victim to circumstance and you can easily experience something different. you are in control. there is NOTHING holding you back. you can fly right now if you want to. you can teleport to japan right now if you want to. there is no such thing as impossible, the only impossibility exists in mind which we know is illusory.

realise the spoon is fake and bend your awareness to live life out of misery, pain and destruction and direct your awareness to love, peace and fun.

606 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every time someone says that Japan doesn't have marriage equality, I think they should be required to add "despite polling indicating that a majority of the population supports same-sex marriage, implementing it is politically unfeasible due to the wording of the US-imposed postwar constitution". I just think they should be required to add that.

672 notes

·

View notes

Text

Admirable Articles of Japan's Constitution

Article 13

All of the people shall be respected as individuals. Their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness shall, to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare, be the supreme consideration in legislation and in other governmental affairs.

Article 15 (Part of it)

In all elections, secrecy of the ballot shall not be violated. A voter shall not be answerable, publicly or privately, for the choice he has made.

Article 16

Every person shall have the right of peaceful petition for the redress of damage, for the removal of public officials, for the enactment, repeal or amendment of laws, ordinances or regulations and for other matters; nor shall any person be in any way discriminated against for sponsoring such a petition.

Article 17

Every person may sue for redress as provided by law from the State or a public entity, in case he has suffered damage through illegal act of any public official.

Article 20

Freedom of religion is guaranteed to all. No religious organization shall receive any privileges from the State, nor exercise any political authority.

No person shall be compelled to take part in any religious act, celebration, rite or practice.

The State and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity.

Article 38

No person shall be compelled to testify against himself.

Confession made under compulsion, torture or threat, or after prolonged arrest or detention shall not be admitted in evidence.

No person shall be convicted or punished in cases where the only proof against him is his own confession.

Article 41

The Diet shall be the highest organ of state power, and shall be the sole law-making organ of the State.

Article 76

The whole judicial power is vested in a Supreme Court and in such inferior courts as are established by law.

No extraordinary tribunal shall be established, nor shall any organ or agency of the Executive be given final judicial power.

All judges shall be independent in the exercise of their conscience and shall be bound only by this Constitution and the laws.

by Dunilefra, working for Fundamental Rights

#Japan#Dunilefra#Politics#Political Reform#World Politics#World Order#Fundamental Rights#Human Rights#Economy#Religion#State Policy#Political Analysis#Constitution#Constitutional Law

0 notes