#Warlpiri

Text

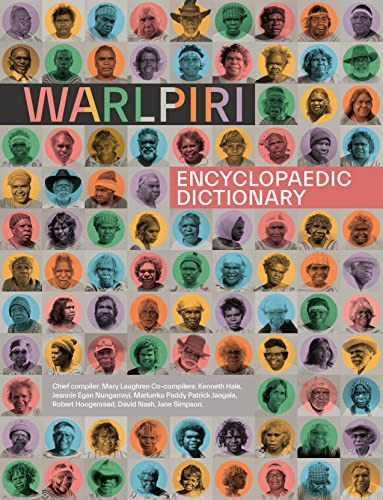

Six decades, 210 Warlpiri speakers and 11,000 words: How a groundbreaking dictionary was made:

You can buy a copy here!

133 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Lingthusiasm Episode 76: Where language names come from and why they change

Language names come from many sources. Sometimes they’re related to a geographical feature or name of a group of people. Sometimes they’re related to the word for “talk” or “language” in the language itself; other times the name that outsiders call the language is completely different from the insider name. Sometimes they come from mistakes: a name that got mis-applied or even a pejorative description from a neighbouring group.

In this episode, your hosts Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne get enthusiastic about how languages are named! We talk about how naming a language makes it more legible to broader organizations like governments and academics, similar to how birth certificates and passports make humans legible to institutions. And like how individual people can change their names, sometimes groups of people decide to change the name that their language is known by, a process that in both cases can take a lot of paperwork.

Read the transcript here.

Announcements:

We’re doing another Lingthusiasm liveshow! February 18th (Canada) slash 19th (Australia)! (What time is that for me?) We'll be returning to one of our fan-favourite topics and answering your questions about language and gender with returning special guest Dr. Kirby Conrod! (See Kirby’s previous interview with us about the grammar of singular they.)

This liveshow is for Lingthusiam patrons and will take place on the Lingthusiasm Discord server. Become a patron before the event to ask us questions in advance or live-react in the text chat. This episode will also be available as an edited-for-legibility recording in your usual Patreon live feed if you prefer to listen at a later date. In the meantime: tell us about your favourite examples of gender in various languages and we might include them in the show!

In this month’s bonus episode we get enthusiastic about some of our favourite deleted bits from previous interviews that we didn't quite have space to share with you. Think of it as a special bonus edition DVD from the past two years of Lingthusiasm with director's commentary and deleted scenes from interviews with Kat Gupta, Lucy Maddox, and Randall Munroe.

Join us on Patreon now to get access to this and 70+ other bonus episodes, as well as access to the Lingthusiasm Discord server where you can chat with other language nerds, and get access to our upcoming liveshow!

Here are the links mentioned in the episode:

‘A grammatical overview of Yolmo (Tibeto-Burman)’ by Dr Lauren Gawne

‘Language naming in Indigenous Australia: a view from western Arnhem Land’ by Jill Vaughan, Ruth Singer, and Murray Garde

Wikipedia List of Creole Languages

Wikipedia entry for Métis/Michif

‘A note on the term “Bantu” as first used by W. H. I. Bleek’ by Raymond O. Silverstein

Lingthusiasm episode ‘How languages influence each other - Interview with Hannah Gibson on Swahili, Rangi, and Bantu languages’

Wikipedia entry for Endonym and Exonym

All Things Linguistic post on exonym naming practices in colonised North America

Tribal Nations Map of North America

Wikipedia entry for Maliseet

OED entry for ‘endoscope’

Wikipedia entry for Light Warlpiri

Language Hat entry for Light Warlpiri

Los Angeles Times article about the use of Diné instead of Navajo

OED entry for ‘slave’

Wikipedia entry for names of Germany

You can listen to this episode via Lingthusiasm.com, Soundcloud, RSS, Apple Podcasts/iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also download an mp3 via the Soundcloud page for offline listening. To receive an email whenever a new episode drops, sign up for the Lingthusiasm mailing list.

You can help keep Lingthusiasm advertising-free by supporting our Patreon. Being a patron gives you access to bonus content, our Discord server, and other perks.

Lingthusiasm is on Facebook, Tumblr, Instagram, Pinterest, and Twitter.

Email us at contact [at] lingthusiasm [dot] com

Gretchen is on Twitter as @GretchenAMcC and blogs at All Things Linguistic.

Lauren is on Twitter as @superlinguo and blogs at Superlinguo.

Lingthusiasm is created by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our senior producer is Claire Gawne, our production editor is Sarah Dopierala, and our production assistant is Martha Tsutsui Billins. Our music is ‘Ancient City’ by The Triangles.

This episode of Lingthusiasm is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike license (CC 4.0 BY-NC-SA).

#linguistics#language#episodes#main episodes#episode 76#names#language names#Arnhem Land#Yolmo#Creole#Kriol#Métis#Michif#Bantu#Swahili#endonym#exonym#Maliseet#Warlpiri#Light Warlpiri#Diné#Navajo#Slavic#German

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring untranslatable words unveils the intricacies of linguistic diversity. Consider the Hawaiian term "Aloha," encompassing love, affection, peace, and compassion – a multifaceted concept difficult to distill into a single English equivalent. In Haitian Creole, "Kouzin" refers to an extended family-like relationship, going beyond mere cousinship.

The Japanese term “Komorebi,” which beautifully captures the interplay of sunlight filtering through leaves. In Spanish, there’s “Sobremesa,” embodying the leisurely time spent lingering at the table after a meal, a social ritual deeply ingrained in the culture.

Moving to German, “Waldeinsamkeit” conveys the feeling of being alone in the woods and the connectedness with nature, a sentiment not effortlessly translated. In Portuguese, “Saudade” encompasses a profound sense of longing, a complex emotional state that doesn’t have a direct equivalent in many languages.

In Russian, “Pochemuchka” describes a person with an insatiable curiosity, while the Swedish “Mångata” captures the shimmering reflection of the moon on water. These examples showcase the intricate relationship between language and culture, emphasizing how some concepts are so intricately woven into the fabric of one language that they resist easy translation.

Korean introduces "Han," representing a complex blend of sorrow, resentment, and enduring resilience. The Chinese term "Yùyī" expresses the profound beauty of a moment that is both fleeting and transient. In Tagalog, "Kilig" encapsulates the exhilarating feeling of being romantically thrilled.

Portuguese contributes "Desenrascanço," embodying the ability to improvise resourcefully in challenging situations. Italian introduces "Sprezzatura," an effortless and nonchalant display of skill and style. Zulu presents "Ubuntu," conveying interconnectedness and shared humanity.

Tongan offers "Faka'apa'apa," a deep respect and humility towards others. Afrikaans contributes "Geselligheid," reflecting a warm sense of togetherness and camaraderie. Navajo introduces "Hozhǫ́," symbolizing beauty, harmony, and balance. In Warlpiri, "Ngarrka-ngku" encapsulates the profound interconnectedness between family and the land.

These examples illustrate the richness of linguistic diversity, where each language crafts unique expressions reflecting the depth of cultural experiences. While it's challenging to cover every language, these glimpses showcase the beauty of untranslatable words across a variety of linguistic landscapes.

#langblr#language#german#hawaiian#‘olelo#deutschland#spanish#portuguese#russian#korean#japanese#navajo#warlpiri#tongan#afrikaans#italian#zulu#chinese#tagalog#filipino#swedish#haitian creole#chatgpt#untranslated

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Languages of the world

Warlpiri (Warlpiri)

Basic facts

Number of native speakers: 2,624

Spoken in: Australia

Script: Latin, 21 letters

Grammatical cases: 0

Linguistic typology: fusional, SVO

Language family: Pama–Nyungan, Ngumpin–Yapa, Ngarrkic

Number of dialects: 3

History

1950s - creation of a spelling system

1974 - the spelling system starts being used in schools

Writing system and pronunciation

These are the letters that make up the script: a i j k l ly m n ng ny p r rd rl rn rr rt t u w y.

Vowels can be short or long. Syllable structure is constrained: syllables begin with a single consonant, followed by a vowel and sometimes by a single consonant.

There is fixed initial stress and vowel harmony.

Grammar

Nouns are marked for number by reduplicating the root.

In Warlpiri culture, it is considered impolite for certain family members to converse, like a woman with her son-in-law, so they use a special style of the language, the avoidance register. This register uses the same grammar but a reduced lexicon.

Verbs are conjugated for tense, mood, person, and number. There are five conjugation classes with distinctive tense and mood endings.

Dialects

There are three dialects: Warnayaka, Wawulya, and Ngalia. However, there is only data for Wawulya.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

girls love 2 spend over an hour reading about pidgin languages nd constructed languages

#im supposed 2 be researching 4 a paper and this is sorta related but also i havent gotten any actual research done yet#personal tag#also. everytime i refer 2 myself as a girl i am not like. misgendering myself.#im saying it in a tumblrina girlblogger who isnt a girl way yannow#anyways.#i learned about light warlpiri#that was very inchresting

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

These Dogs Have Dreaming

In Yuendumu, dogs are more than just pets. They’re family members, friends and spiritual guardians. Dogs and dingoes have an ancient symbiotic relationship with Warlpiri people, a bond that continues to this day

Photograph: Francis Macindoe

Australian Life photography competition 2023

#francis macindoe#photographer#australian life photography competition#australia#yuendumu#dogs#spiritual guardians#warlpiri people

0 notes

Text

By offering and grasping each other's penis – said to represent "paying with one's life" – the men make an avowal of mutual support and goodwill between them, or symbolize and solidify the agreement they have reached during the settling of a dispute.

"Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity" - Bruce Bagemihl

#book quote#biological exuberance#bruce bagemihl#nonfiction#support#goodwill#agreement#dispute settlement#indigenous australians#walbiri#aranda#warlpiri people#arrernte people#mutual trust

0 notes

Text

This might feel slim by today’s understanding of Indigenous ancientness, but in the 1950s and 1960s, scientific dating confirmed Australia’s human history reached well beyond any sort of written archival record. Moving Australian History into the deep past, thousands of years before colonisation brought with it Western forms of history-making, established a radical new timescale for the discipline. [...] As well as comprehending that colossal timescale, there has been the challenge of how to acknowledge and translate the understandings and experiences of time held by Australia’s First Peoples. [...] In Stanner’s 1956 essay, “The Dreaming”, he attempted to tease out a translation of Indigenous temporality. [...] “One cannot ‘fix’ The Dreaming in time: it was, and is, everywhen.”

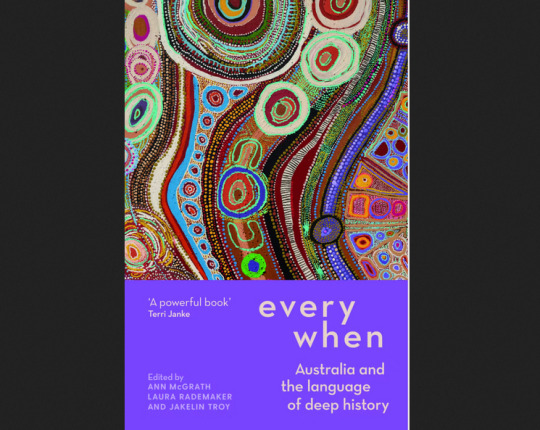

Over 50 years later, that commitment to translation and conversation is the focus of an impressive collection of essays, Everywhen, edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker and Jakelin Troy. “The concept of everywhen,” they explain, “unsettles the way historians and archaeologists have conventionally treated time — as a linear narrative that moves toward increasing progress and complexity.”

“We take ‘deep history’ to include the histories that long precede modernity, the medieval era and the few thousand years generally known as ancient history”, McGrath and Rademaker explain in the book’s introduction. But this is more than simply going back in time, they add: we consider that deep history is largely Indigenous history, so it cannot be slotted into European history’s existing archival boxes or temporalities. [...]

---

Clint Bracknell describes various Noongar words for time and the past, including the illuminating term nyidiŋg, which means “long ago/cold” – pointing perhaps to a cultural memory of the last Ice Age.

Ngarigu woman and linguistic anthropologist Jakelin Troy locates time in Country itself. “We do not see ourselves as being in a solely terrestrial space”, she offers.

Land, water, and sky all connect as one space, and the stories of ancestral figures and the creation of features on the land, in the water, and in the sky are all connected.

Shannon Foster, a D’harawhal knowledge keeper, also explores the uniqueness of D’harawhal historical connections that sit outside Western conceptions of linear time. “There is no purpose for us as D’harawhal people to know a time or an age”, Foster insists. “Dates add nothing to our culture … We know their value. It has nothing to do with time”.

Specific terms shared in the book, such as the well-cited word jukurrpa in Warlpiri, as well as bugarrigarra (from the Yawuru language in the West Kimberley), and amalawudawarra (from Anindilyakwa, on Groote Island) confirm the encompassing, fluid and cosmological hues of Indigenous languages that meld time and place through Ancestors and Country. [...]

---

The ethical imperative of this exercise in translation and conversation drives the collection. As McGrath and Rademaker explain, for most of the 20th century the way many national histories were taught in schools and publicly memorialised was as if nothing much happened until Europeans arrived. [...]

“Time” has been a critical component of that colonising architecture, as Dipesh Chakrabarty and Priya Satiya have shown — determining Indigenous people had “no time”, or existed outside historical, linear time (and therefore outside historical “progress”). [...] This was “a country without a yesterday”, the writer Godfrey Charles Mundy insisted in 1852. [...]

===

There is an explicit sense in this volume of the obligation to recover the deep past and engage Indigenous temporalities, without relegating them to a sort of “dreamtime” that is only mystical and spiritual. Critically, it also highlights the generosity of Indigenous historians, writers and knowledge-keepers [...].

Or, indeed, if they should be: I couldn’t help but wonder, does the history discpline’s reach into Indigenous deep time threaten to colonise a space which has so far eluded Western epistemology? (Although, the cost of not trying might be even worse.) [...]

The ethical demand to engage with, acknowledge and include Indigenous forms of history has extended the discipline into new, albeit sometimes challenging, epistemological territory around the world.

---

Headline, images, captions, and text as published by: Anna Clark. “’Dates add nothing to our culture’: Everywhen explores Indigenous deep history, challenging linear, colonial narratives.” The Conversation. 8 March 2023. [Some paragraph breaks and contractions added by me.]

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's put this into its own post: with appropriate resources, you can teach any subject in any language. Obviously the absence of resources in minority languages is a problem, indeed in some sense the problem, of language revitalization. And it's a difficult to solve one, but let's bracket it for now. You can teach math and science and music and history and pretty much everything else a child needs to know in Scottish Gaelic or Lakota or Warlpiri, if you've got the resources. So the idea that education in these languages would harm a child's education in a general sense is ridiculous.

There is one very important skill, though, that you can't teach in a minority language: the majority language! But this is a pretty tractable problem, frankly. Kids are going to acquire competence in the majority language automatically, especially in cases like the above, where bilingualism is near universal. In fact, even with immersion schooling in the minority language, they are reasonably likely to be more competent in the majority language, if it's what they're using outside of school all the time. So it's really not about teaching the majority language at all, but teaching literacy in the majority language. Given the success that e.g. the Nordics have had teaching English literacy, in a society where English has to be taught as a second language to begin with, while the rest of their schooling is in their native language, I don't think this is an especially difficult thing to achieve. Or, well, of course it's difficult, in the way that all education is difficult, but I should say that it's clearly tractable.

Given how much personal sadness and pain language death causes for people, how much of artistic and intellectual value disappears when languages die, and so on, I think it's plainly worthwhile to make an effort to solve these tractable-seeming problems. And given that bilingualism is generally regarded as cognitively beneficial (although I'm not familiar with the research, so I can't speak to its validity), I think bilingualism generally is probably worth encouraging. So the argument that education in a minority language is detrimental to the child just doesn't seem to hold water. It's also the argument that lead to things like the Indian residential school system here in the US, which is more-or-less principally responsible for indigenous languages being endangered here in the first place.

#society#linguistics#imo the only possible case opponents could make here is 'it's expensive'#it is expensive and it's worth being serious about the amount it would cost to do this with every minority language and where that money#would come from#I still think it's hugely important#but obviously money has to come from somewhere#but all the arguments that it's actually bad are just retreads of colonial propaganda

165 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I was wondering if you had any advice regarding where I could find information on the evolution of signed languages. I want to create a Warlpiri-style consign language that is essentially a manual version of the spoken language, so I am mostly concerned with the phonological (cherological?) evolution. Any help would be much appreciated!

First, there is no such thing as a sign language that's based on a spoken language. That's a misconception. Sign languages evolve on their own, and do so independently, apart from any spoken languages around them. There are plenty of borrowings from spoken languages into sign languages, either in the form of finger spelling, or in the form of a calque (where the meanings of a word's etymology are translated directly into another language), but those are simply borrowings (e.g. no amount of borrowings from Latin and French is going to make English a Romance language).

There are signed forms of languages, but these aren't really separate languages. They're better understood as orthographies—a way to visually interpret a spoken language. You can certainly do that, but, again, that's not really a signed language.

Thanks for the ask!

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

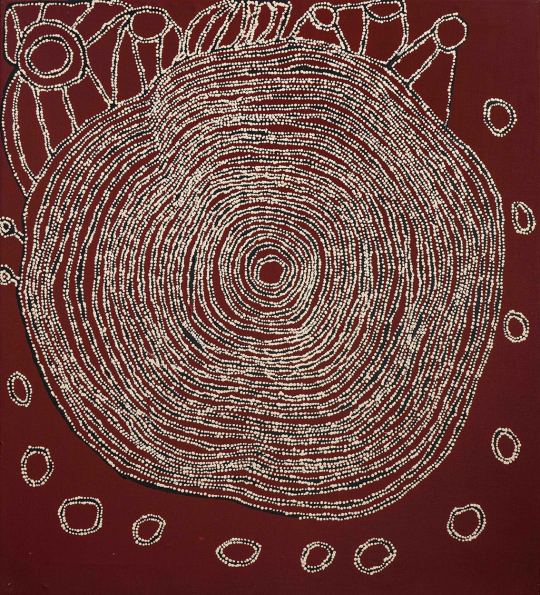

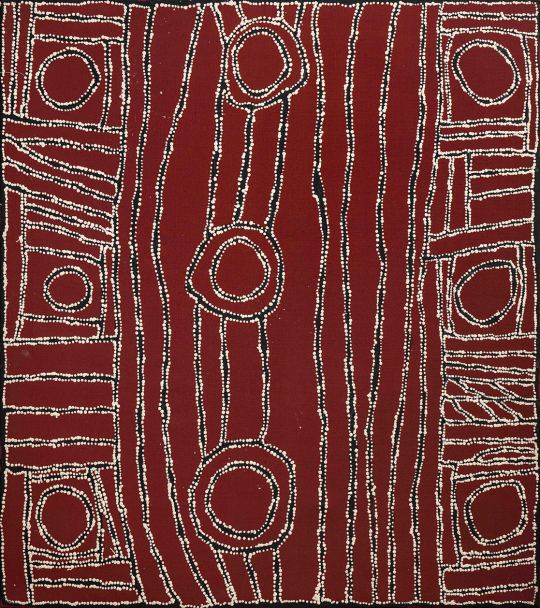

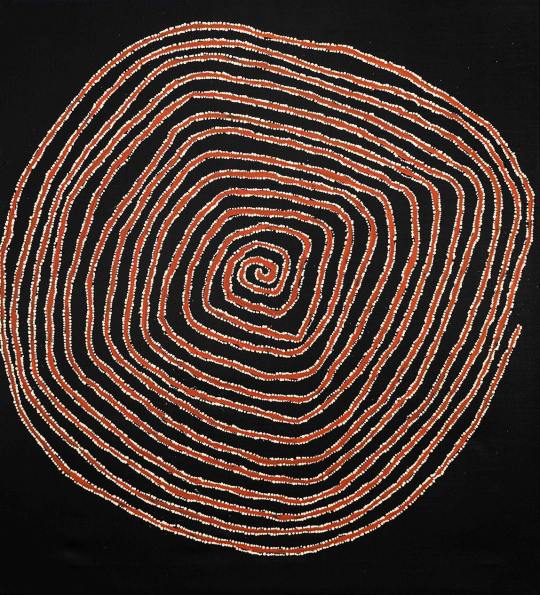

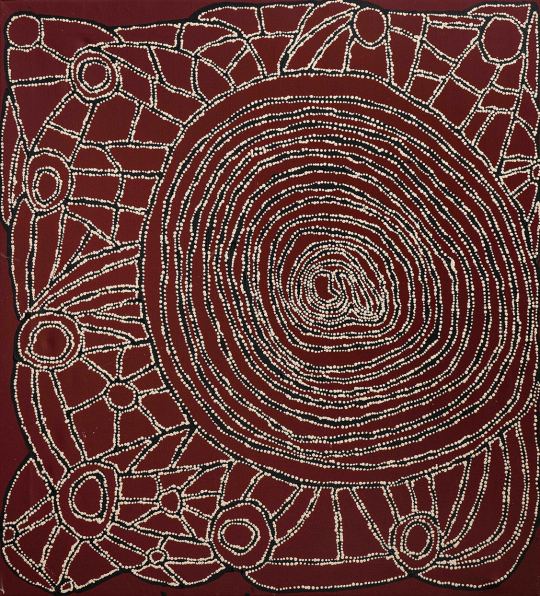

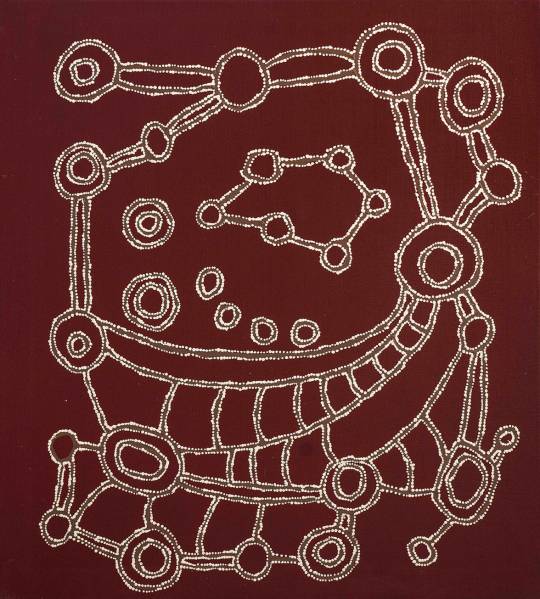

MARY BROWN NAPANGARDI WARLPIRI, B. 1953

Mary Brown Napandardi's works often reinterpret scenes from women's ceremonies including body painting designs, song lines and dance cycles. She also depicts dreaming stories passed down through generations. She harnesses traditional iconography and symbols to depict flora, fauna and significant landmarks including expansive sand hills and rockholes.

Napangardi was born around 1953 within a bush camp at Mandarine in Central Australia. Growing up, she lived a very traditional lifestyle; learning and caring for the land as well as learning important cultural knowledge and the dreaming stories of her country. During her childhood, Napangardi and her family were relocated by a white man to an Aboriginal settlement called the Yuendumu Community in Central Australia.

Napangardi began painting in the early 1990s. In 2005, she began painting for Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Corporation in Yuendumu. These sacred stories translated within her work have been passed through her family for generations.

https://umberaboriginalart.com.au/.../44-mary.../overview/

From the ‘Western Desert Women’ – a Group Exhibition 2022

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alma Nungarrayi Granites - Night Sky

Aboriginal art, acrylic on linen

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is an example of Athena Granites Nangala artwork . Her work tells the ancient story of the Warlpiri Seven Sisters story using a very modern acrylic pour technique. Yubu Napa Art Gallery

#yubunapa #centralaustralia #aboriginalart #RedCentreNT #alicesprings #mpwarnte

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"From Narrm to Yuendumu, Justice for Walker, Abolish the Police!! One Three One Two!!!"

Mural in Narrm/Melbourne demanding justice for Kumanjayi Walker, a 19-year-old Warlpiri Indigenous man who was shot and killed by police in the remote Aboriginal community of Yuendumu, Northern Territory in November 2019.

The officer who killed him, Zachary Rolfe was later acquitted of a murder charge by an almost entirely white jury, with no Indigenous jurors, despite Aboriginal people being 30% of the population in the NT.

Thousands of people rallied in Alice Springs in the days following the murder of Kumanjayi, and further protests followed in cities around Australia. After the acquittal of Rolfe, the campaign demanding Justice for Walker has continued.

270 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Blak Lens: emerging Aboriginal photographers join forces – in pictures

Uncle Eddie Peters, Proud Torres Strait Islander

Colleen Raven (Strangways) is a South Australian Arabana and Northern Territory Mudbura Warlpiri woman and the founder of Nharla Photography. She is interested in using film, photography and other mediums to represent and preserve First Nations’ stories, languages and cultures. She is also committed to showcasing her culture by telling stories through an Aboriginal lens and to passing on the skills and the knowledge she has learnt over the years to the next generation of emerging artists

#photographer#aboriginal photographer#south australian arabana and northern territory mudbura warlpiri#nharla photography#culture#australia#first nations#colleen raven (strangeways)#black & white photography#torres strait islander

1 note

·

View note